Text

...And Other Stories

There are not many books I re-read immediately after reading them. At least lately. When I was 14 I think I read the same six books round and round. (They're stuck in me now, for better or worse; if I had a scan or an X ray, they'd probably show up on the screen.) But when your house contains almost 100 unread books you do sort of think, Well, I'll just stick a Post-It Note on that one before I put it back on the shelf, which will remind me to re-read it later on. And in 2015 when you finally do some dusting - probably because you're being evicted from your cosy damp shoebox in violent Wood Green after the rent went to £800 a month - you will see it and think Ah! I have to re-read that some day. And you will forget.

But! Sometimes a book comes along that demands re-reading instantly. This happened to me last year with Deborah Levy's Swimming Home. The patterns and symbols of physical objects, and their psychological resonances for the characters in the story, were so deft and expert that I had to go back through, tracing and trailing them, to unlock the code they suggested. It was great, like a choose-your-own-adventure book for people into Freud and Barthes. It happened again last week, with All Dogs Are Blue by Rodrigo de Souza Leao.

Like Swimming Home, All Dogs Are Blue is very interested in psychological patterns. But while Swimming Home is set over a holiday, and builds in tension as the numbered days progress, de Souza Laeao's novel is set in a criminal mental asylum, where the days flow hopelessly, time goes elastic as the drugs kick in, and the confinement causes the narrator to disappear into his memories and imagination as the days go on. The pattern here is the narrator's labyrinthine mental structure: the out-of-sequence revelations about his imaginary friends Rimbaud and Baudelaire, when they first turned up and what they signify to him, and of course the stories of how he ended up here.

The final section of the novel is almost standalone, in that we seem to be reading the survival techniques of the narrator as he remembers - or possibly invents - the situation that led him to being incarcerated, which involves being beaten by police, gathering thousands of followers, and finding a universal language that animals speak. The writing here achieves a smooth, frail and emotionally pure beauty (credit to the translators, Zoe Perry and Stefan Tobler, as well as de Souza Leao himself) and some of the images from earlier - alien abduction, the swallowed microchip, the toy dog and the imaginary friends - recur, finding their place in the narrator's fractured mind.

Alien abduction also appears in another book I read recently, Quesadillas by Juan Pablo Villalobos. Like Swimming Home and All Dogs Are Blue, this is published by the fairly small, fairly new publishing press And Other Stories, and it's their second by the author, after his debut novella Down the Rabbit Hole in 2011. I was sceptical of And Other Stories at first because they are based in High Wycombe, which is far too close to Reading, cultural and emotional void of my adolescence - as the NME once put it when writing about The Cooper Temple Clause, "a series of roundabouts near Slough - but I put prejudices aside because Swimming Home and Down the Rabbit Hole were so good.

The alien abduction of Quesadillas is, as with All Dogs Are Blue, also couched in unreliability. The story is of a poor family living in a shack on a hill, and the two youngest children go missing from a supermarket while their mother is haggling over food at one of the counters. The oldest son, Aristotle, insists that it was aliens, and so he and the narrator - second oldest, Orestes - break into the home of their rich Polish neighbours, steal supplies, and go on a pilgrimage to the site from which Aristotle insists the twins were abducted. Why should anyone believe him? Especially with his habit of lying, of emotionally manipulating others, and of mistreating Orestes throughout the story?

But depending on how you want to read the last chapter, this alien abduction is real. I can only talk about this through massive spoilers, so apologies if you don't want to know: at the end of the book, a glorious and hilarious deus ex machina appears in the form of everyone the book has mentioned so far - the lost twins, Aristotle, neighbours, politicians, bulls, cows, and a spaceship - to create a glorious and silly happy ending that wrong-foots the reader with a certain nonchalance. Well, why shouldn't it happen, here in the land of magic realism? it says. Did it really happen? Is the narrator - or Villalobos himself - sticking two fingers up and saying, "Don't believe me? Fine. But it's my story"; or is he making a comment on how Mexico is treated internationally, and the sort of magical turnaround that would be required for things to actually get better? Or did these humble, tragic figures just deserve a bit of joy?

Quesadillas has a marvellous structure, too: it operates almost like an old-fashioned children's book - Five Children and It, perhaps, or The Chronicles of Narmo - where every chapter is a standalone short story, but a few threads run through it reminding you that this is going somewhere. The loss of the twins is a tale seemingly with a conclusion; Orestes making friends with his neighbours' son is the same; his life on the street as an amateur conman, too; and the final story brings these all together, in a wild scene of exuberant comic joy. Unexpected and delightful, it demands to be read while grinning.

I don't have room now to talk about Down the Rabbit Hole or Helen DeWitt's Lightning Rods, two other And Other Stories books I've loved, but trust me - they are as strong and smart as Quesadillas is. These books give you a real sense of the publishing house's identity: a taste in books so full of personality, you feel you can trust them, whatever they print. All of these books have been fascinating, thought-provoking and involving. There's a whole load more of theirs I haven't read yet, of course. But I'd say five out of five so far is a pretty good strike rate.

#and other stories#translation#juan pablo villalobos#deborah levy#swimming home#down the rabbit hole#quesadillas#all dogs are blue#rodrigo de souza leao

1 note

·

View note

Text

There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbour's Baby

COMING SOON - responses to Tracy Thorn and James Lasdun's recent memoirs. But as if to counteract discussion of fact and memory, I've been re-reading Ludmilla Petrushevskaya's collection There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbour's Baby. ("Selected and translated with an introduction by Keith Gessen and Anna Summers", it says under the title.)

Petrushevskaya's stories are really great. They are referred to as "scary fairy tales" on the front cover, although they don't always feel that way in the book itself. My favourite of them, 'Marilena's Secret', is a story about an enormous woman who is secretly two women - sisters (Maria and Lena) who once danced together at a travelling show, until a magician fell in love with one, and when they said that they would never be parted, he turned them into one joint woman. Every night, however, when they are alone, they separate into themselves again, and dance. Whoever tries to divide them, the magician says, will be turned into a dysentery grub. As the huge Marilena, she becomes a strong woman at the circus, and something of a celebrity for the acts she can perform with the strength of two women, until her fame gets her in trouble again - this time by a man who poses as a suitor with a clinic where she can diet, who actually tries to kidnap Marilena and steal her money. But when she is kidnapped, she separates into her real selves again, and when those selves start to draw back together into one huge woman, the guard keeping them prisoner is trapped between them. He tries to cut himself free, but in fact breaks the curse: he separates them, and is turned into a dysentery grub. Maria and Lena become dancers again; the wizard is terrified that their magic is stronger than his, and Vladimir - the fake suitor who kidnapped them - finds that his place has now become infected with dysentery. "Sometimes one evil defeats another, and two minuses make a plus!" Petrushevskaya interjects.

Gessen and Summers' introduction is a particularly interesting one. Petrushevskaya's writing went unpublished for years in Russia. "The same editor who first published Solzhenistyn in the Soviet Union in Novy Mir in the early 1960s met with Petrushevskaya in 1968 to tell her that, in her case, there was no hope."

Why?

Gessen and Summer suggest her themes of suffering are "too dark, too direct and too forbidding". But is it also that, when we read fantasy, we see it as allegory?

Magic is everywhere in this collection. There is a re-telling of the Orpheus in the Underworld myth, 'The Arm', about a Colonel who dreams that his dead wife comes back to him, but her face is hidden behind a veil, and he must never lift it. he does, of course, and finds that behind it she is rotting: but then he wakes up, and it seems to be a metaphor for something else. The threat in the dream when he lifts the veil - "now your arm is going to wither" - is not quite true, but his arm is damaged, and is more in the state of the wife's face in the dream. Another, 'A New Soul', opens, "You can recognise them, but only if you yourself are one of them." There is something of Angela Carter and Edgar Allan Poe about these stories, although the voice itself is more Brothers Grimm, with its otherworldly yet straightforward storytelling, and the plainness with which it tells fantastical events.

What I think it comes down to is this: Petrushevskaya's stories do not read like pure fantasy, and certainly not whimsy. There is the straight-forward narrative style, for example, suggesting all of this happened down the road, and then there are the parallels she draws between the supernatural and the natural (the rotting face of the dream, the rotting arm of reality) make her stories seem like they are saying two things at once. Is she really just telling the story of a woman who has a secret, and is really two beautiful sisters? Or is she telling the story of oppression, and how people without malice are manipulated and tricked by selfish, stronger people? They don't read like escapism, or entertainments for children; they read more like Animal Farm - they read with a serious intent and with a sharpness of vision. When we read something so direct, and with such a good understanding of the human heart, we start to reflect on our own lives. We question if we have ever behaved like the characters, or if we have been in similar situations. We may never have had withered arms or been split in two, but we might all have felt like different people inside than out. These stories aren't necessarily metaphors for anything - but their core, like all good writing, makes us see things anew, and question ourselves and the world around us, which is presumably what got her in trouble with a government that so fiercely and famously controlled the freedom of expression of its people.

Beyond these stories, Petrushevskaya has also written a novel about the Soviet intelligentsia, so she is not only a fairytale author. This, too, might have had an effect on how the government saw her: why would someone who can also do realism suddenly start writing non-realism? What is she saying?

What Petrushevskaya is saying, of course, is up to the reader. As with many fairy tales, her stories are highly open to interpretation, and I'm glad that she was eventually published, and equally glad that she was subsequently translated into English so that mono-linguists like myself can appreciate her work (and, as in this whole post, pontificate blindly about what she's really up to with her stories). Penguin have also recently released another anthology of her translations, There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister's Husband, and He Hanged Himself. This one is subtitled "love stories" - although, as the title suggests, I'm guessing these aren't all happy ones. Looking forward to getting hold of it.

#translation#ludmilla petrushevskaya#there once lived a woman who tried to kill her neighbour's baby#keith gessen#anna summers#fairy tales

0 notes

Text

Frances Ha

I know this is a blog about books, but it's also a blog of my enthusiasms; it's just my enthusiasms are usually what I'm reading. But while I fail to find anything interesting to say about Katherine Mansfield (she's brilliant!), Margaret Atwood (Cat's Eye is perfect but The Blind Assassin is too long!) and Daniel Woodrell (I'm so excited about The Maid's Version that my palms are sweating as I type this!), I'm going to talk about Frances Ha.

I was nearly put off seeing Frances Ha because of all the reviews comparing it to Girls. Of course I watch Girls - I'm white and at the tail-end of my 20s - but I find it a frustrating experience. Zosia Mamet is the only one of them who's actually doing any acting; the socio-economic tunnel vision is painful at times; the character journeys in the second series were all over the place and made almost no sense toward the end. (Perhaps, actually, my problem with Girls can be summed up by that scene in the second series where Hannah and Elijah go to see a DJ duo called Andrew Andrew. I thought that idea - of an identically-dressed gay DJ duo, one of whom changed his name to Andrew so they matched - was hilarious and such an on-point parody of hipster culture. Then I watched "inside the episode" on YouTube, in which Lena Dunham waxed lyrical about Andrew Andrew. They're real, and she wanted to feature them on the show. Sigh.)

So. Frances Ha. Yes. Like Girls, it's about being broke in Brooklyn (and other parts of New York), and it's the journey of a young woman as she tries to find her place in an artistic environment - here as a contemporary dancer. But where it transcends Girls is its presentation of that world. It isn't "here are what some people's lives are like and isn't that interesting", but an open-ended, identifiable story of an imperfect human trying to find a way to put her notion of her self into what she wants to do in life. It's about everyone's adult coming-of-age, it's about friendships as relationships, and it's about the room of one's own that people need if they want self-expression - artistic or otherwise.

The story is simple enough. Frances is 27. She lives with her best friend, Sophie, who looks like Anastasia Krupnik would if Lois Lowry had let her grow older than 13. Sophie works at Random House and has a rich money-making boyfriend called Patch, who she's slightly embarrassed about having grown to love. He isn't cool and hipsterish, like Frances and herself. He's just a straightforward jockish frat type who loves her. Frances, however, has just broken up with her boyfriend, because he wants to move in together and get cats, and she... doesn't.

What does Frances want? There are already enough films about being lost in the big city, here to make your mark, but unsure what that is, and although Frances Ha has one foot in that genre, it's more about how someone goes about doing what they love - contemporary dance, in Frances's case - and goes about finding a way to make that work. Is she selling out if she takes an office job at the dance company where she's currently an apprentice? Will that stop her being a dancer or choreographer? Is it giving up, exactly, if she does so? While Sophie moves up and away - into marriage, a job, then to Tokyo - Frances just gets to hear about what she's up to from everyone else, all of whom seem to be more settled. They have apartments, which Frances stays in, either on sofas, the floor, or by scraping together $950 a month for a box room in Chinatown. It's observed at one point that Frances doesn't have "her shit together", and the film, ultimately, is about how we find a way of getting that shit together. We compromise, we grow up, we recognise our individual strengths and weaknesses, which include our limitations, and where we draw the line about something.

Frances's journey is presented as a series of vignettes, but anyone who's vaguely familiar with Robert McKee's Story will see that it's actually very tightly structured. Things go wrong. She does stupid things. She's badly in denial at points, lying about what's really happening, going back to her old university as a waitress and RA, being bitched at by someone years younger than herself about starting her shift late. She impulsively goes to Paris, alone and on a bad-deal credit card. (Here, book fans, she reads the LYDIA DAVIS TRANSLATION OF THE WAY BY SWANN'S, BECAUSE IT'S ONE OF THE BEST TRANSLATIONS OF ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS, WRITTEN BY ONE OF THE BEST PEOPLE, AND TRANSLATED BY SOMEONE JUST AS EXCELLENT.) She thinks that while getting herself into debt in Paris, she'll meet up with a friend who's moved there. And of course the friend finally gets back in touch as Frances is in the taxi on the way back home in New York. She is rude to strangers at dinner parties, and she lies about how things are going, to her friends and herself. She hits a very low ebb. Then, having got there, she wises up, faces the problems, and does the difficult things that will help her achieve something. She takes the office job at the dance academy and makes use of the rehearsal space that comes with it. She puts on a small but charming show that she has choreographed. It's a small victory, but this isn't about money or fame. She has found a way to prove who she is, using what she loves.

And, in the process, she has done what all those addresses - those box rooms, friends' apartments and sofas - were adding up to. She has found a small but pleasing apartment. She has found a room of one's own.

(There's also, along the way, a funny and poignant scene in which a drunk Sophie - who's quit her job to move to Tokyo with Patch - returns to New York, wine-fuelled and foul-mouthed and moody. She ralphs in Frances's trashcan, then lies back on the bed and says, "I miss my job." God, I wish there were more films about people longing for great jobs. Let's be honest here, fellow victims of capitalism, we're all more likely to have that be the story of our lives.)

Frances Ha is a magnificent film. I wasn't wild about co-writer and director Noah Baumbach's last film, Greenberg. It seemed like it couldn't decide who was the main character, and its key subject - that we make stupid decisions and let our flaws drive us, but we're trying, damn it - wasn't best presented through the decision to split the focus between the mostly-unlikable Greenberg (Ben Stiller) and the seemingly-likable-but-underdeveloped Florence (Gerwig). But focusing just on Frances here (Gerwig again, also the co-writer) allows the audience to really get to know her, to appreciate the weaknesses and sharp edges of Frances, and it's made with a breezy openness that allows us in, rather than shutting us out the way Greenberg did. Winning performances from everyone involved, too, especially Gerwig. Her physicality is note-perfect, from her heavy trudge in her downtrodden moments to her defiant, joyful run through New York, and the lunchtime dance routine she carries out near the end. I highly recommend it, my six unfaithful readers.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One by one they appear in

the darkness: a few friends, and

a few with historical

names. How late they start to shine!

but before they fade they stand

perfectly embodied, all

the past lapping them like a

cloak of chaos. They were men

who, I thought, lived only to

renew the wasteful force they

spent with each hot convulsion.

They reminded me, distant now.

True, they are not at rest yet,

but now that they are indeed

apart, winnowed from failures,

they withdraw to an orbit

and turn with disinterested

hard energy, like the stars.

—Thom Gunn, “My Sad Captains”

Photography Credit Vicky Slater

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

May We Be Forgiven

Like an addict falling off the wagon, lately I have just been BUYING SHITLOADS OF BOOKS instead of reading the unread ones on my shelf. Most recently, AM Homes's May We Be Forgiven.

I am no Homes specialist - I've read her two books of short stories, and gave up on The End of Alice because the cod-Lolita narration bothered me - but I was very intrigued by May We Be Forgiven, and it won the was-Orange-now-Baileys-prize, so I felt it deserved some attention. It is a strange book - a rollercoaster with regular loops and turns, seemingly at random - but very enjoyable nonetheless. It is not perfect (is any book?), but it does some brilliant things as it makes its imperfect way.

The first few pages almost seem to be from another novel altogether. The narrator, Harry, starts in the past tense, looking back on a family Thanksgiving where his brother George - an arrogant, successful bully who he despises - is holding court at the dinner table while Harry and George's wife clear the table, their fingers dipping into "unnameable goo" on the plates. There's internal work here: Harry admits to jealousy, confusion, and a certain self-hatred that's mixed with his hatred for George. Then George accidentally drives at top-speed into another car, killing the parents of a young boy, and in the fall-out from this, in a fractured mental state, he comes home to find Harry in bed with his wife, and beats her to death with a lampshade.

(This isn't a spoiler, by the way. We're on page 7.)

The novel uses this as its narrative impetus, but it changes as a result: the rest of the book is told in a breakneck present tense, and Harry very rarely - until the last fifty pages or so - stops to really think about things. He never wants to admit his emotions, and in fact tries not to have them. Whip-smart dialogue and precise, curt description gives each scene a feeling of self-contained drama, as if something has changed, or been suggested, and we're not sure how or why. Harry's thawing-out and his growth as a character are only reflected on explicitly at the end. The rest of the time, the reader has to do the work: from what people say to Harry and how they behave towards him, we know how he's coming across, and how he really feels. When a policeman he's argued with visits him in hospital, we realise that Harry is floundering and people think he's lonely. Considering he and George are so furious with each other, there's very little reflection or back-story as to their childhoods: a few scenes, some in dialogue when he goes to see George in prison, give us an idea of their similarities, differences and fights. It's not quite the book that the first few pages suggested, but then perhaps because May We Be Forgiven is a Great American Novel, I was expecting it to play along with that genre's recent conventions. Other Great American Novels of the last decade have been things like Freedom, where we get treated to each character's past, scrutinizing the minutiae of their adolescent memories to chart their psychological journey. Homes isn't interested so much in dramatic revelations from Harry's past: she's interested in his present, event after event, as he is pummeled in the chest until his heart starts beating again. Blackly comic material - lesbian paedophiles, strip Laser Quest, regular toilet humour and the mention of circumcision as "a rich man penis" - do battle with strokes, bar mitzvahs, blackmail, the life of Nixon, abandoned senile pensioners, and a very bizarre espionage sequence in which someone is abducted via helicopter.

It's a strange book: not lumpen, exactly, and definitely not baggy (the sentences are crisp, the dialogue pacey); instead it is simply an oddly-shaped novel, in which you can never work out where anyone is headed or what will happen to them. George becomes more of a figure than a person, a bad version of Harry who doesn't learn and grow as Harry does, and we never dwell too long on why George's children, Nate and Ashley, might be acting the way they do. Is it okay that Nate has become an adult so early? Should there be more to Ashley's coming-of-age experiences? It is only when they break down - when they talk about missing their mother, or get angry about things changing - that we get an insight into their character journeys, and what's going on with them. And because of Homes's talent for dialogue, these moments are wrapped up quickly, with wit and good phrasing. At times this can make the novel feel like it's treating weighty subjects lightly, as Harry fails to really ask himself - or let the kids talk - about the repercussions of the novel's opening pages. But I sense this is a book that benefits from re-reading: once you know Harry's quirks of narration, his refusal to investigate his feelings or look too deeply for answers for fear of what he might discover, you can put more time into the subtext of the story, where the answers to some of these questions might be found. Whatever its faults, this book can't fail to hold your attention, and it doesn't contain a single bad sentence - pretty impressive for a 500-page novel.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A late addition to the problems of The Great Gatsby...

A month after everyone else, I finally went to see The Great Gatsby. First impressions: Carey Mulligan and Leonardo DiCaprio are good. Tobey Maguire is slightly miscast, but then Nick Carraway is a difficult character - being the narrator, he does not always justify his actions or self-analyse closely. There's no moment in the novel where he explicitly explains why he decides to engineer a meeting between Gatsby and Daisy, and he also withholds judgment when it comes to their affair. It's presumably to do with his feelings about Tom, and knowing that Tom is seeing Myrtle, but Fitzgerald generally allows Nick a lot of projection: the feeling of the prose, of his descriptions of his surroundings, give us a sense of mood, and of his feelings. Luhrmann isn't interested in this. His vision extends only so far as confection: ridiculous colourful bombast, everything pumped to the nth degree. As a result, Maguire - playing Nick with a hipsterish vibe, as someone fresh from college who doesn't know who he is and isn't all that invested in finding out - blends into the ridiculous opulence, almost disappearing. The Valley of Ashes doesn't highlight Nick's dark mood, or give him a sense of unease. It's just a great big impressive valley of ashes, and Nick wanders around in it, the size of a pin.

Mulligan does a lot better. Like DiCaprio, she has great screen presence - mostly helped by the fact that she's knockout gorgeous and suits the flaspperish fashions of Daisy Buchanan very well. If the camerawork weren't so hyperactive, more time would be given over to everything that is going on under Daisy's skin - whether she really is shallow and selfish, or whether she's a woman making fluttering attempts to escape her misogynistic husband, only to find herself drawn back to him by his controlling nature and her need for emotional and financial security. Daisy is one of the more complex characters here, and Mulligan gets her pretty much right.

Darling let's go for a cruise on the Titanic

The best I can say for it: the showdown scene in the hotel room, where Gatbsy and Tom Buchanan fight for her, is mostly brilliant, and the most successful part of the film. Of course, this is Luhrmann, so subtlety is completely out the window, and as the scene goes on, pictures fall off walls, etc. Just in case you didn't get it that PEOPLE ARE ANGRY AND BAD STUFF IS HAPPENING NOW.

The other bad: everything is so very, very overdone. When someone makes a veiled reference to Gatsby's money not being honestly earned, parties collapse and turn to screaming and misery, or the soundtrack ramps up to 100 decibels, or fireworks go off, or shooting stars cross the sky above their heads. Whenever someone's angry, they're not just angry, they're angry in slow motion, the hair on their heads vibrating, the jowls whipping from side to side.

QUIETEN DOWN WE ARE ACTING HERE!!!!!

Here is the key problem: The Great Gatsby is a story cleverly told. It has a smooth, lyrical style that doesn't draw attention to itself, but now and then, through the flow and pattern of language, story, dialogue and subtext, suddenly hits you with a beautiful sentence that draws meaning from its surroundings and makes the events of the characters' lives seem universal. Luhrmann knows this, but he destroys the context: he rips the good sentences out of the book and has them plastered all over the screen. Out of sequence and written in burning letters across the sky, they become fridge-magnet homilies, obnoxious and overwrought.

Yes, I know. Fitzgerald is a stylist - a brilliant writer on a line-by-line level - and yes, that ought to translate to a stylish film. But he is a musical stylist of phrases and cadences, of dialogue that suggests what isn't spoken, and of pinpointed lines that describe and analyse. We know these sentences are good; but this is a FILM ADAPTATION. Turn the sentences into cinema. Don't just leave them flapping about all over the screen like injured birds. Half of the time, Tobey Maguire is reading a paragraph in voice-over, while the words appear on the screen, and everyone acts out what's already being said and shown. ("Gatsby believed in the green light" - violins swell, green light consumes the screen, DiCaprio reaches for it in lustful wonder, etc.) Fitzgerald's words are now lyrical bonbons beside Luhrmann's confectionary visuals. White letters swirl on New York streets, falling from some typewriter cloud in the sky. Cameras whizz and zoom for no good reason. It's like being repeatedly punched in the face by a fist made of crystal sugar. It's excruciating.

Then there is the matter of the music. I'm fine with some of it. I enjoyed it, it was nice. But when you pick incredibly famous pieces of contemporary music - Back to Black, Crazy in Love, etc - you do these characters a worrying disservice. I was fine with it in Moulin Rouge, because Moulin Rouge was its own story, took place in its own alternate reality, and had its own set of rules. It was a theatrical comedy-drama with a circus feel, an original story that existed like a stage show onscreen. Its anachronistic music was part of its concept, and its fantasy world existed alongside that. The Great Gatsby is a lyrical tragic drama, and these characters have to matter to us if you want us to be sad when they die, or to want them to get together, or to feel the hopelessness when their world collapses. When you pop them in front of a load of pastel cakes while Crazy in Love plays behind them, you are drawing attention to the artifice of your creation, and screaming, Look at me! Look at the film! Look at the clever fancy things the film is doing! Nick, Daisy and Gatsby collapse into paper dolls when you do this, and we can't invest ourselves in their love story because it doesn't have any feeling of truth to it.

Meanwhile, Jordan Baker is sidelined disappointingly (especially annoying as she's such a good, striking actress) and one of the most important facts of her character - that she may or may not have cheated in a high-profile golf game, and could therefore be as self-serving, financially manipulative, and unfeeling towards the poor as the Buchanans turn out to be - disappears. Her golfing is mentioned the first time we meet her, but nothing comes of it until she pinpoints the first time she saw Gatbsy to the day she got a certain golf club. It just leaves you thinking: Oh, yes. She plays golf. Good for her. Then, when Tom and Nick drive back from the car crash with her, and she carries on as before, inviting Nick in for dinner, we've had no build-up to this part of her character - her cold, shrewd remove from those without privilege. She's suddenly just a flapper girl who's emotionally indifferent. She doesn't care about the death, so she's a bitch. And she's out of the story. Bye!

And the car crash itself! It is SHOCKING AND SAD when Myrtle dies. Okay? It is not sad when she goes spinning through the air, pearls flying majestically, rotating in slow-motion like a dancer. The way that her husband puts a gun in his mouth at the end - IN TIME TO THE MUSIC - is just embarrassing. This isn't a pop video. CHARACTERS ARE DYING HERE. There is literally nothing stylish and musical about blowing your own fucking brains out. Do not glamorize the concept. Oh, you did.

Alright I'll blow my brains out, but only if Lana Del Rey sings as I do it

Perhaps this highlights the difference between Fitzgerald and Luhrmann. Fitzgerald avoids the showdown itself: Nick isn't there when Gatsby is shot. Gatsby is shot offstage; we learn it later. But this isn't a film that goes for this kind of quiet, realistic tension and revelation. This is a film that wants you to see Gatsby tumbling through the water, blood spiralling out of him, guns being fired behind him, etc etc. It romanticizes the image of someone dying. It wants every shot to look like a perfume advert, every frame to be a still for a poster campaign. And in doing so it sacrifices the emotional impact of its story. Why be sad that Gatsby is dying when you can admire how amazingly you're seeing him do it?

Overall, the films biggest flaws aren't even to do with it being unfaithful to the book, or anything like that. It's just that it's so stylised, so silly, so artificial, and so bald, that the whole thing ends up feeling hollow and unlovable. In Moulin Rouge, Satine belonged to that made-up, chocolate box world; here a made-up world is inflicted on Gatsby and Daisy. Yes, their world is full of artifice - but it's one that Fitzgerald was interested in, and wanted to scratch the surface of to see what was underneath. Luhrmann just wants GLITTER! at all times. The stunning world of the book is one that Gatsby created, to win Daisy over and get his happiness with her. Luhrmann's made-up world has no purpose to look good beyond looking good. Shallow, silly, and dreadful, dreadful, dreadful.

#the great gatsby#f scott fitzerald#baz luhrmann#books#film#carey mulligan#leonardo dicaprio#tobey maguire

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The End of the Story

Lydia Davis has won the International Man Booker Prize. The good thing about this, as opposed to the normal Booker, is that it is given for a body of work. So even if Philip Roth's mojo has been off since about 2003, he still deserved it. And Alice Munro doubly so. (Because however much praise she gets, doesn't it always feel like Alice Munro is underappreciated? I can't work that one out.) So the usual Booker arguments about the merits of different styles of books, or whether the author's being awarded rather than their specific novel, go out the window. Hurrah!

And of course Davis is a true recognisable artist, who has spent the last 30 years developing a style that is completely her own, in her curious, inscrutable, meta-mundane style, using rhythms and repetitions and sometimes deliberately clunky or plain language to create humour, observation, interrogation and a very unique sense of philosophy beneath it. And to point out just how weird language is, at heart, or rather, how weird our daily use of language is. (I want to say it's a worthy win, but other than Marilynne Robinson, I don't know any of the other writers, so I can't say for sure.)

So, in the spirit of literary excitement, now is the perfect time to read Davis's The End of the Story, which I have in its old Serpent's Tail/High Risk imprint from the mid-90s. Already, on page 3, it's making me want to laugh and I can't work out how. Here's a sample paragraph:

The trip had been uncomfortable so far, because I felt oddly estranged from the man I was with. The first night I drank too much, lost my sense of distance in the moonlit landscape, and tried drunkenly to dive into the white hollows of the rocks, which appeared as soft as pillows to me, while he tried to hold me back. The second night I lay on my bed in the motel room drinking Coca-Cola and barely spoke to him. I spent all the next morning on the back of an old horse at the end of a long line of horses, riding slowly up into a single cleft in the hills and down again while he, annoyed with me, drove the rented car from one rock formation to another.

I think I find it funny because of that description - almost symbolic - of that horseride "into a single cleft in the hills and down again". The flatness makes it seems like a sort of Herculean labour of pointlessness, set against the image of a car driving "from one rock formation to another". It really suggests the oddness of their relationship, and sets the mood for how she's feeling. Brilliant stuff. Now for the next 220 pages.

0 notes

Photo

Well that was easy. I love Herta Muller and Sylvia von Harden, so why not make them Herta Von Harden together. <333

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I have this exact edition; I stole it from my mother. Currently re-reading before I go and see the film.

Already worried: HOW will the film introduce Gatbsy in the way he is in the novel? i.e. Nick Carraway is talking to him for a while before we realise he's Gatbsy. Sort of sets up his character for the whole book, his mystery, his inner life, his anonymity. Hard to do when Leonardo DiCaprio is going to glide onscreen looking Hollywood....

“The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald. In The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald brilliantly captures both the disillusion of post-war America and the moral failure of a society obsessed with wealth and status. But he does more than render the essence of a particular time and place, for in chronicling Gatsby’s tragic pursuit of his dream, Fitzgerald recreates the universal conflict between illusion and reality.

888 notes

·

View notes

Photo

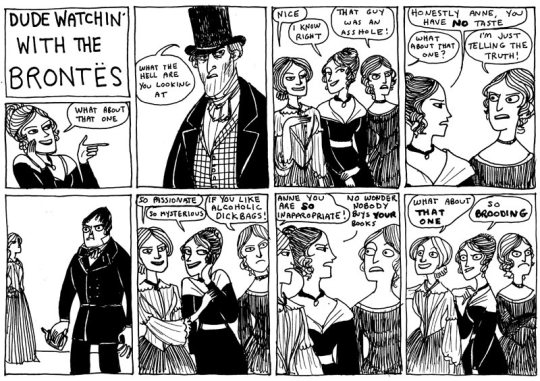

"Anne why are you writing books about how alcoholic losers ruin people's lives? Don't you see that romanticizing douchey behavior is the proper literary convention in this family! Honestly." - Kate Beaton, Hark! A Vagrant

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

A quick history of last month's books

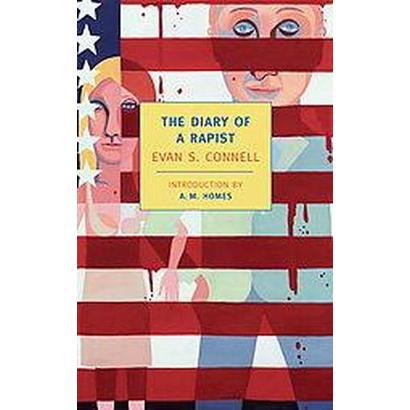

Recently I've read Agnes Grey by Anne Bronte, The Diary of a Rapist by Evan S Connell, As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner, The Drama of the Gifted Child by Alice Miller, and Hawthorn & Child by Keith Ridgway.

Agnes Grey is like someone's blog from the 1800s. I especially like the bit where she uses four exclamation marks in a sarcastic aside about her young charges actually waiting for their lessons. ("Climax of horror!!!!" - it's very un-Bronte.) Poor Anne. I shall dig up that Kate Beaton cartoon strip, I think.

The Diary of a Rapist was depressing. It was a good portrayal of a mind unravelling, contradicting itself, and justifying its darkness; overall, I thought it could have gone deeper into the complexities of the changes in gender roles, women's equality etc, that were feeding Earl's mental illness and feelings of inadequacy. Slightly feels like a cop-out to write a madman's diary - half the work of how he became such a monster is done by the first page in that way.

As I Lay Dying was good overall, blackly comic, very unfair, and grotesque at times. I want to read more Faulkner but couldn't go straight into another: the prose is too dense, too twisty. I needed to come up for air often, and re-reading chapters along the way was a necessity. That is in no way a bad thing, of course. The tragedy of Jewel was very affecting, and so re-reading was a rewarding experience, deepening the characters' connections and tragedies.

The Drama of the Gifted Child required a lot of re-reading as well. I read it because it is referenced in Alison Bechdel's Are You my Mother?, which I loved. It didn't "change my life", as Bechdel is promised by a bookseller in her memoir, but it gave me a lot to think about regarding my childhood, my parents' childhoods, and how those fed back on each other. And, of course, the childhoods of people I knew during my childhood, and what might have led them to behave in certain ways. (Ooh, cryptic. This isn't livejournal or Agnes Grey, I realise.)

Hawthorn & Child was good. The writing is taut and smart and the dialogue is great; the stories don't quite all hang together - a couple towards the end I lost interest in, whereas the opening three or four are fantastic. I think it almost suffers by trying to pretend it's a novel, when it is really a series of interlinked short stories: as I realised, slowly, that each chapter was not a progression, but a self-contained object with a few recurring tropes/characters/events, at first I was disappointed and annoyed; by the end, I'd made peace with it being this and was able to appreciate it for what it really was. But I'd like not to have expected more from it, really, as it coloured my experience of the middle third.

Now on to East of Eden. This has been on my bookshelf for years. I'm only four chapters in but it's already beautifully written. Even when characters are being beaten up and then followed around with a hatchet.

#empty the bookshelf#agnes grey#anne bronte#diary of a rapist#evan s connell#as I lay dying#william faulkner#drama of the gifted child#alice miller#hawthorn and child#keith ridgway#east of eden#john steinbeck

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jinkx Monsoon, my favorite. I love this person as a man and woman.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm sure no one cares what I have to say about this, but since I've read NW, I thought I would share my thoughts.

I'm a Zadie Smith fan. I bought NW the day it came out and was looking forward to it. (I'm such a Smith nerd, in fact, that when it turned out that one main character was a Hanwell, I was delighted.) And I know this is a promotion piece from Penguin's tumblr, but "not enough praise can be heaped on this... amazing book" seems like it will give unrealistic expectations in potential readers, setting the book up for something it isn't.

So.

Here's how I felt about NW. Smith is a talented, fluid writer, good at psychological insights, and at creating three-dimensional characters at the drop of a hat (she can just do it); she's naturally and spontaneously funny, rather than a show-off comic writer who tries to manoeuvre her story around her jokes. She is especially good at finding moments in which issues of class, race and the individual are played out. She does this well in On Beauty, when Zora tries to get Carl into her creative writing class, and the effects it has on the behaviour of the novel's characters (including Carl and Zora themselves). I feel that she does it less successfully in NW, particularly during the Natalie/Keisha material. Keisha's predicament is fascinating: she's an intelligent, academically high-achieving girl who has to choose her university by which one she can afford to get to on the train. (She can't afford a ticket to Cambridge, so there's no point in applying; she'd never make the interview.) When she returns from university, with a law degree and a white middle-class partner, asking to be called Natalie, she is torn between personal desires and social expectancy: should she work for the community she comes from, or should she get a job that will give her personal comfort but won't help her conscience to help others from her background?

There's a brilliant, brilliant issue under discussion here - class, race, social responsibility, and of course the fact that every social group is made up of different people, who are difficult and have their own drives and ambitions, and some want to have children and live on benefits and some don't, and so on. The set-up is all ready to plunge into the complexity of this, and yet the narrative shies away from really going for it. Natalie creates an online persona, using her birth name of Keisha, and starts having rough sex in council houses. And then she realises she's ruining her family, so she runs out on them, and thinks about jumping off a bridge. It's so neat, and so truncate, and so shallow compared to what the story could have done with this predicament. Smith is so concerned with concision and brevity this time around (NW is much, much shorter than her previous three novels) that she just cuts the whole thing short. The topic under discussion is so deep, so dense, and so asking to be talked about, that when she just stops it's completely jarring. It's like she knows there is dark and impressive subject matter here, but can't work out how to do it without the book getting longer than she wants it to be, so she finds a tidy symbol for Natalie's split-personality predicament, and ends it there.

The weird thing is, she's so able to do it. Anyone who's read her Obama essay in Changing My Mind, and the memoir material that follows it, knows she's got the intelligence, insight and linguistic skill to deal with this sensitively and engagingly. So why doesn't she?

Perhaps because of my other problem with NW, the book's voice(s). I know that intertextuality is partly Smith's thing - I know that each of her books takes another book or two and reinvents them (Midnight's Children, Pnin, Money, Howards End, etc) but NW so nakedly uses blueprints of other books that sometimes it feels like a puppet show, or pastiche. She's such a good writer. She doesn't need to imitate Woolf, or Mrs Bridge, or Life: A User's Manual. But - and again, this is something she writes about beautifully in Changing My Mind - she's used these books as scaffolding, to get her story down, to help her put the novel itself together, but she hasn't taken the scaffolding down. And perhaps that's what leads to the novel not quite achieving its potential: the voices she's chosen to take the lead from don't quite work in the territory she really writes best about, which is cross-cultural London and everything it represents to her; all the issues, contemporary and timeless, that it carries with it.

Writing this blog has kind of made me feel like a bastard, but hey. I still like Smith, I still really like her. I still want to see more of her essays and reviews especially, and am hopeful for more novels. Ideally, though, novels where she doesn't try to copy other writers. She really is good enough to just be herself from page one.

What should you be reading this week?

Well, it really should be Zadie Smith’s NW, as she picked up her third literary honour of the week today. Named as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists on Monday, shortlisted for the Women’s Prize on Tuesday and now (on Wednesday) she has been shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje prize too. Not ebough praise can be heaped on this remarkable author and her amazing book.

Read what the Guardian say about it here.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Feeling awkward reading this bad boy on the tube. Full thoughts about how different it is to Mrs Bridge coming soon...

0 notes

Photo

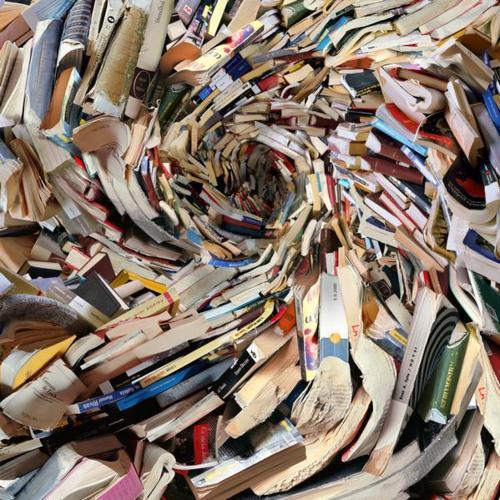

the bottom photo looks to me like a cosy warren to crawl in for a nap

Alicia Martin’s Amazing Book Sculptures

5K notes

·

View notes

Quote

You know, if only one is able to kick the habit of all this squalor that’s become second nature to us and takes a look at the life of our upper classes as it really is in all its shamelessness, one can see that what we live in is a sort of licensed brothel - Pozdnyshev

The Kreutzer Sonata, Leo Tolstoy (via antonymsynonyms)

1 note

·

View note