Text

remember if you wake up feeling sick and your whole body hurts the best course of action is to jack off and moan like a girl

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

[AH: Yes, it’s just correct.

CM: It was okay to be with her because we all knew men were really fuckers and there were a lot of “okay” women acknowledging that. Read: white and educated…. But that’s not why I “came out.” How could I say I wanted women so bad I was gonna die if I didn’t get me one soon? You know, I just felt the pull in the hips, right?

AH: Yes, really… Well, the first discussion I ever heard of lesbianism among feminists was: “We’ve been sex objects to men and where did it get us? And here’s when we’re learning how to be friends with other women, you got to go and sexualize it.” That’s what they said! “Fuck you. Now I have to worry about you looking down my blouse.” That’s exactly what they meant. It horrified me. “No no no,” I wanted to say, “That’s not me. I promise I’ll only look at the sky. Please let me come to a meeting. I’m really okay. I just go to the bars and fuck like a rabbit with women who want me. You know?”

Now, from the outset, how come feminism was so invested in that? They would not examine sexual need with each other except as oppressor-oppressee. Whatever your experience was, you were always the victim. Even if you were the aggressor. So how do dykes fit into that? Dykes you wanted tits, you know?

Now, a lot of women have been sexually terrorized and this makes sense, their needing not to have to deal with explicit sexuality, but they made men out of every sexual dyke. “Oh my god, she wants me, too!”

So it became this really repressive movement, where you didn’t talk dirty and you didn’t want dirty. It really became a bore. So after meetings we ran to the bars. You couldn’t talk about wanting a woman, except very loftily. You couldn’t say it hurt at night wanting a woman to touch you… I remember at one meeting breaking down after everybody was talking about being a lesbian very delicately. I began crying. I remember saying “I can’t help it I just… want her. I want to feel her.” And everybody forgiving me. It was this atmosphere of me exorcising this crude sexual need for women.]

the persistent desire, ed. joan nestle, 1992.

583 notes

·

View notes

Text

Konks for sale! 1 careful ownder (deceased)

447 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yuzen-painted geisha hikizuri. Late-Meiji era (1890-1912). This is a remarkable antique hikizuri - geisha dancing dress - with its vivid hawk, wave and pine motifs vividly created utilizing masterful yuzen-painting, sumi e painting, and silk and metallic embroidery. 48" from sleeve-end to sleeve-end x 67" height. In Japan, the hawk and pine tree in combination usually represents the power and longevity of the Tokugawa shogun. The Tokugawa shogunate was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which now is called Tokyo. The Tokugawa shogunate ruled from Edo Castle from 1603 until 1868, when it was abolished during the Meiji Restoration. The Kimono Gallery.

480 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shape-shifting is one of fairy tale’s dominant and characteristic wonders: hands are cut off, found and reattached, babies’ throats are slit, but they are later restored to life, a rusty lamp turns into an all-powerful talisman, a humble pestle and mortar becomes the winged vehicle of the fairy enchantress Baba Yaga, the beggar changes into the powerful enchantress and the slattern in the filthy donkeyskin into a golden-haired princess. More so than the presence of fairies, the moral function, the imagined antiquity and oral anonymity of the ultimate source, and the happy ending (though all these factors help towards a definition of the genre), metamorphosis defines the fairy tale.

—Marina Warner, From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

["The body is conceived of as part of nature and so as separated from the realm of reason. Accordingly it has little to teach us. It has been silenced, as have other aspects of nature, governed by laws of its own. It is given and passive so without a voice in its own experience. It is uncivilised, if not dirty, and so it has to be discounted. It presents the threat of nature against culture and civilisation. Since we only inhabit civilisation as it has been defined by modernity to the extent that we live as rational beings, we learn to deny these aspects of our natures. We learn to live as though they do not exist at all.

Within the identification of masculinity with reason, men become the protectors of and gatekeepers for this dominant vision of modernity. We set the terms on which others can be permitted to enter. Others have to pay the price of construing themselves as 'rational agents' in the particular ways this has been conceived.

As men, we learn to live a lie. We learn to live as if we are 'rational agents' in the sense that we live as if we live beyond nature. We learn to live as if our emotional lives do not exist, at least as far as the 'public world' is concerned, for this is where these identities are most securely lived out. It is as if modernity expects us to live, not as if our natures have been effectively controlled, but as if they did not exist at all. For to live out the ideal that modernity presents us with is to exist as rational beings alone. We learn to live in our minds as the source of our identities.

If we had our way as men it would be that our emotional lives did not exist at all, for they serve only to get in the way of our realising the goals and purposes that are set by reason alone. This provides the only meaning and dignity that our lives can have. Kant is clear that only if we act out of a sense of rational duty do our actions have any moral worth at all. To act out of our desires and inclinations, even if this be out of feelings of care and kindness, yields our actions no moral worth at all. For Kant we are simply doing what we want to do and this has to be selfish."]

victor j. seidler, from unreasonable men: masculinity and social theory, 1994

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am so glad I am in charge of the spa playlist, the disco elysium soundtrack is surprisingly soothing.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

["Marx's discussion of alienation and estrangement still manage to haunt much sociological discussion because they provide insights into qualitative conditions of being. It is crucial for Marx that alienation is not thought about as a 'psychological' condition, for it is inseparable from the material situations that workers find themselves in, separated from the means of production, within a capitalist mode of production. It is crucial for Marx that as wage labour we exist as commodities with a distinct price on our heads. We have to recognise that as far as capital is concerned, we exist as means which are dispensable as soon as the profitability of production is brought into question.

In learning to treat our labour as a commodity, we are left in a contradictory situation in relation to our existence as creative beings. This is because we cannot meaningfully separate our labour from ourselves as if it were a separate possession that we could use at will. It is Locke's vision of the possessive individual who can somehow be separated out as an owner of his or her qualities. It is this vision of the person as an owner of qualities that he or she is free to dispense of at will, that informs a capitalist ethic. It still sustains libertarian conceptions, such as that defended by Robert Nozick in Anarchy, States, and Utopia.

Marx contests that this vision of the self and its relation to its qualities as part of his critique of capitalist notions of freedom. Marx's vision of people as creative beings suggests a discussion of needs, capacities, and qualities that have to be fulfilled if people are to realise themselves. This is in constant tension with a rationalism that is attempting to construe such notions as 'fulfillment' and 'realisation' in externalised ways, as matters of achieving ends and goals that have been defined by reason alone. But Marx rejects these terms, since what matters is not simply our existence as rational beings but our growth and development as creative beings in all its different facets. This involves the fulfillment of our natures within this life, rather than the subordination of our natures for a salvation that is offered in the next. In this crucial respect it challenges the Protestant vision that tacitly informs modernity."]

victor j. seidler, from unreasonable men: masculinity and social theory, 1994

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

so many people asking how to see butches, have a working class job and ride public transportation, go, find them

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

victor j. seidler, from unreasonable men: masculinity and social theory, 1994

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

victor j. seidler, from unreasonable men: masculinity and social theory, 1994

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the results of wanting a hysterectomy is getting a hysterectomy and that’s wonderful

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

judy grahn, from another mother tongue: gay words, gay worlds, 1984

706 notes

·

View notes

Text

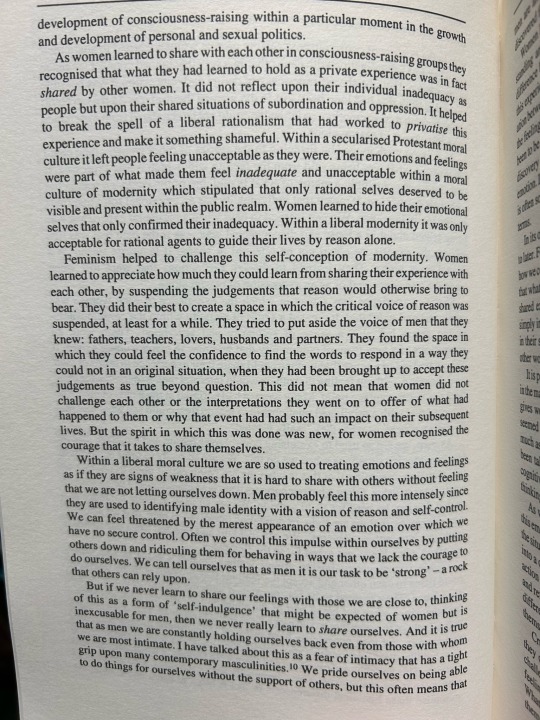

["REASON AND EXPRESSION

Within the context of consciousness-rasing groups women learned to share their experience of subordination with each other in a way that helped connect language to experience. Out of shared experience of denial and oppression it was possible to speak a truth that had long been lost to the women themselves. As reason could not be separated from emotion, so language could not be separated from experience as an instrument of reason alone.

As women were moved by listening to the stories of other women, they could not separate what was being said from the feeling with which it was expressed. It if as if truth is not simply a matter of what is said, but of the contact a person has with their experience. It meant that individuality has an emotional form that finds expression in language. Women learned to hear when a particular experience was being talked about in a loose and disconnected way— as if the pain that was tied up with the experience could not be released or shared if language stayed on a mental level alone. They learned to discern distinctions that were lost when language was conceived of as an expression of reason alone.

Sharing experience was a way in which the experience of each woman was confirmed and validated. It created a sense of equality within the consciousness raising group but also a sense of solidarity and sisterhood. These were all expressions of a new form of community that was new in many women's lives. It was created out of a sense that women could share their experiences in terms of their own choosing, without feeling that others would interpret their experience for them from a superior vantage point. Many women had suffered at the hands of men who assumed that with a privileged relationship to reason they could say what was best for their partners, or what they "really wanted."

As men, we are so used to exercising control over reason and language that we barely recognize situations when we do this. We are so ready to offer solutions to that situation, assuming that this is what we are being called upon to do, that we rarely learn to listen. Often what our partners want is an experience of being listened to, but this can be hard for us to provide. We are so used to using language as a way of proving that we are right, or defending ourselves as men, that we automatically use it to "solve problems." We can feel hurt and rejected when our advice is not taken when it was not asked for in the first place.

Within consciousness-raising groups women created a space in which they could listen to each other and accept the feelings that emerged with the sharing of experience. They seemed to be less threatened with the sharing of emotions and feelings, since often not being part of the situation they did not have to respond defensively or in a way that would make these feelings go away. This is not to argue that women and men necessarily have different relationships to their emotional lives but that these relationships are formed within particular cultural and historical settings. This has changed over time and there were periods in which heterosexual men were more easily expressive emotionally with each other. I do not want to minimise these historical differences. In fact it helps to place into context the development of consciousness-raising within a particular moment in the growth and development of personal and sexual politics.

As women learned to share with each other in consciousness-raising groups, they recognised that what they had learned to hold as a private experience was in fact shared by other women. It did not reflect upon their individual inadequacy as people but upon their shared situations of subordination and oppression. It helped to break the spell of a liberal rationalism that had worked to privatise this experience and make it something shameful. Within a secularised Protestant moral culture it left people feeling unacceptable as they were. Their emotions and feelings were part of what made them feel inadequate and unacceptable within a moral culture of modernity, which stipulated that only rational selves deserved to be visible and present within the public realm. Within a liberal modernity it was only acceptable for rational agents to guide their lives by reason alone.

Feminism helped challenge this self-conception of modernity. Women learned to appreciate how much they could learn from sharing their experience with each other, by suspending the judgements that reason would otherwise bring to bear. They did their best to create a space in which the critical voice of reason was suspended, at least for a while. They tried to put aside the voice of men that they knew: fathers, teachers, lovers, husbands, and partners. They found the space in which they could feel the confidence to find the words to respond in a way they could not in the original situation, when they had been brought up to accept these judgements as true beyond question. This did not mean that women did not challenge each other or the interpretations they went on to offer on what had happened to them or why that event had such an impact on their subsequent lives. But the spirit in which this was done was new, for women recognised the courage it takes to share themselves.

Within a liberal moral culture we are so used to treating emotions and feelings as if they are signs of weakness that it is hard to share with others without feeling that we are not letting ourselves down. Men probably feel this more intensely since they are used to identifying male identity with a vision of reason and self-control. We can feel threatened by the merest appearance of an emotion over which we have no secure control. Often we control this impulse within ourselves by putting others down and ridiculing them for behaving in ways that we lack the courage to do ourselves. We can tell ourselves that as men it is our task to be 'strong'— a rock that others can rely on.

But if we never learn to share our feelings with those we are close to, thinking of this as a form of 'self-indulgence' that might be expected of women but is inexcusable for men, then we never really learn to share ourselves. And it is true that as men we are constantly holding ourselves back even from those with whom we are most intimate. I have talked about this as a fear of intimacy that has a tight grip upon many contemporary masculinities. We pride ourselves on being able to do things for ourselves without the support of others, but this often means that men are alone and friendless. At some level we often envy what women have discovered for themselves through the Women's Movement.

Women learned that to share their vulnerability was a way of building understanding and connection with each other. They also learned that there was a difference between accounting for their experience in rational terms and sharing this experience with others. The latter situation helped to heal the cultural separation between reason and emotion. As they shared their experiences they also shared the feelings that were tied up with it. To have put the emotions aside would have been to be false to their experience and themselves. This is in itself an important discovery which challenges the prevailing cultural distinction between reason and emotion. It is part of what makes this experience difficult to share, for what happens is often so rich, yet it seems to slip away as soon as it is described in conventional terms.

In its own way this raises issues of meaning and interpretation that I will return to later. For the moment, it is enough to draw attention to the ways in which it shifts how we conceive the relationship between thought and action. As women recognise that what they had taken to be a private and personal experience of suffering is a shared experience that grows out of the subordination of women, they are not simply interpreting their experience in different ways. There is an important shift in their sense of confidence and self-worth as they learn, through the support of other women, not to turn these feelings against themselves.

It is part of a process of empowerment as women locate or ground their emotions in the material situations in which they find themselves in their relationships. If this gives women greater confidence as they learn to identify and name feelings that seemed to have no names, it is a process that affects their emotions and feelings as much as what they think about themselves and the world around them. If this has been talked about as a 'change of consciousness,' this brings into question the cognitive or intellectualist frameworks within which we have been grown used to thinking about 'consciousness' in both philosophy and social theory.

As women learn to draw support from each other, they learn how important is this emotional and mental support in their being able to both question and change the situation in which they find themselves. This tends to bring thoughts and actions into a different relationship with each other, as women recognise that they take action in their lives, for instant in validating their relationships with other women and refusing to put those aside because of the demands that men make, so they feel differently about themselves. As women learn to define what they want for themselves they take a different kind of control of their lives.

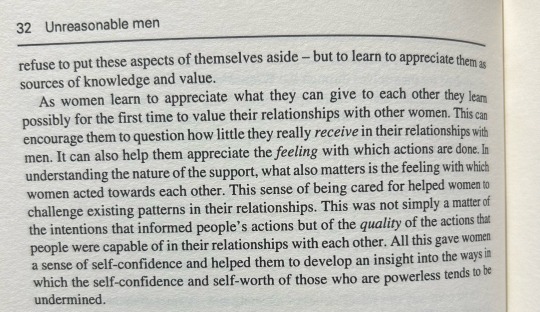

Crucially this is not a matter of dominating their emotions and desires so that they can do what they have decided through reason alone. Rather it involves a challenge to this very rationalism, as women learn to appreciate their emotions and feelings as helping them to define what they value and what matters in their lives. What becomes important is the relationship that women are able to build with themselves as they make more connection with their emotional selves. This is to refuse to put these aspects of themselves aside— but to learn to appreciate them as sources of knowledge and value.

As women learn to appreciate what they can give to each other they learn possibly for the first time to value their relationships with other women. This can encourage them to question how little they really receive in their relationships with men. It can also help them appreciate the feeling with which actions are done. In understanding the nature of the support, what also matters is the feeling with which women acted towards each other. This sense of being cared for helped women to challenge existing patterns in their relationships. This was not simply a matter of the intentions that informed people's actions but of the quality of the actions that people were capable of in their relationships with each other. All this gave women a sense of self-confidence and helped them to develop an insight into the ways in which the self-confidence and self-worth of those who are powerless tends to be undermined."]

victor j. seidler, from unreasonable men: masculinity and social theory, 1994

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

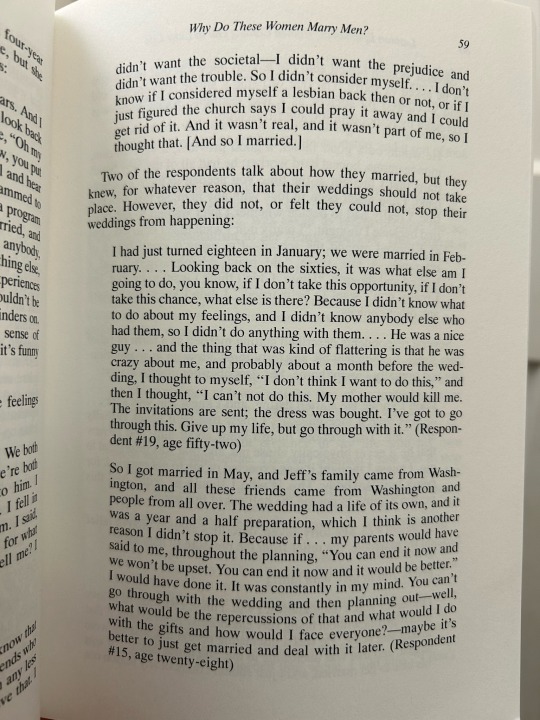

["Respondent #3, age fifty-eight, had a very important, four-year relationship with the woman she roomed with in college, but she either consciously or unconsciously repressed the feelings:

My roommate in college and I lived together four years. And I think we definitely both had those feelings... And I look back now on some of the letter she wrote, and now it's like, "Oh my God, why didn't I see that at the time?" But you know, you put the blinders on so tight and you try not to see and feel and hear things that aren't according to what you were programmed to do. Even though I was a pretty free spirit, I still had a program to go to the university, graduate, eventually get married, and have kids. I was programmed by myself more than anybody, but of course, those were my role models. And so anything else, like falling in love with my roommate and having experiences there, would have thrown me off that track, and I wouldn't be the same person that I thought I was. So I put the blinders on. Imagine teaching Phys Ed. and not having much sense of lesbian relationships. I had those blinders on so tight, it's funny I didn't run into brick walls. They were so tight!

Respondent #5, age forty-one, fought and resisted the feelings she had for women, thus consciously repressing them:

I was twenty-two when I met him. He played guitar. We both played guitar. So we met at the Bible study, and we're both Swedish, and he was very cute. I was attracted to him. I thought he had great eyes, a great face, great body. I fell in love with him. He asked me... why did I marry him. I said, "Because I was in love with you".... He feels hurt for what has happened. "If you knew this, why didn't you tell me? I would have walked away from you."

[You didn't know?]

Well, I knew I had feelings for women, but I didn't know what that was a legitimate choice for me to make. I had friends who were lesbians, and I didn't judge them or think them any less than me, but for me, I wouldn't allow myself to have that. I didn't want the societal— I didn't want the prejudice and didn't want the trouble. So I didn't consider myself.... I don't know if I considered myself a lesbian back then or not, or if I just figured the church says I could pray it away and I could get rid of it. And it wasn't real, and it wasn't part of me, so I thought that. [And so I married.]

Two of the respondents talk about how they married, but they knew, for whatever reason, that their weddings should not take place. However, they did not, or felt they could not, stop their weddings from happening:

I had just turned eighteen in January; we were married in February... Looking back on the sixties, it was what else am I going to do, you know, if I don't take this opportunity, if I don't take this chance, what else is there? Because I didn't know what to do about my feelings and I didn't know anybody else who had them, so I didn't do anything with them... He was a nice guy.... and the thing that was kind of flattering is that he was crazy about me, and probably about a month before the wedding, I thought to myself, "I don't want to do this," and then I thought, "I can't not do this. My mother would kill me. The invitations are sent; the dress was bought. I've got to go through with this. Give up my life, but go through with it. (Respondent #19, age fifty-two).

So I got married in May, and Jeff's family came from Washington, and all these friends came from Washington and people from all over. The wedding had a life of its own, and it was a year and a half preparation, which I think is another reason I didn't stop it. Because if... my parents would have said to me, throughout the planning, "You can end it now and we won't be upset. You can end it now and it would be better." I would have done it. It was constantly in my mind. You can't go through with the wedding and then planning out— well, what would be the repercussions of that and what would I do with the gifts and how would I face everyone?— maybe it's better to just get married and deal with it later. (Respondent #15, age twenty-eight.)

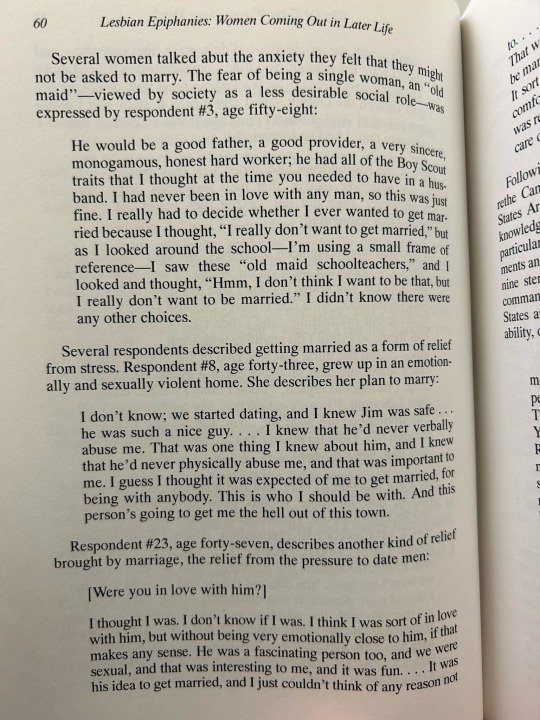

Several women talked about the anxiety they felt that they might not be asked to marry. The fear of being a single woman, an "old maid"— viewed by society as a less desirable social role— was expressed by respondent #3, age fifty-eight:

He would be a good father, a good provider, a very sincere, monogamous, honest hard worker; he had all of the Boy Scout traits that I thought at the time you needed to have in a husband. I had never been in love with any man, so this was just fine. I really had to decide whether I ever wanted to get married because I thought, "I really don't want to get married" but as I looked around the school— I'm using a small frame of reference— I saw those "old maid schoolteachers" and I looked and thought, "Hmmmn, I don't think I want to be that, but I really don't want to be married." I didn't know there were any other choices.

Several respondents described getting married as a form of relief from stress. Respondent #8, age forty-three, grew up in an emotionally and sexually violent home. She describes her plan to marry:

I don't know; we started dating, and I knew Jim was safe..... he was such a nice guy..... I knew that he'd never verbally abuse me. That was one thing I knew about him, and I knew that he'd never physically abuse me, and that was important to me. I guess I thought it was expected of me to get married, for being with anybody. This is who I should be with. And this person's going to get me the hell out of this town.

Respondent #23, age forty-seven, describes another kind of relief brought by marriage, the relief from the pressure to date men:

[Were you in love with him?]

I thought I was. I don't know if I was, I think I was sort of in love with him, but without being very emotionally close to him, if that makes any sense. He was a fascinating person too, and we were sexual, and that was interesting to me, and it was fun.... It was his idea to get married, and I just couldn't think of any reason not to.... I was trying on experiences like people try on clothes. That was part of it. It was also a big relief to me in some ways to be married because then I didn't have to deal with guys anymore. It sort of took care of the whole thing... I also wasn't very comfortable with the whole idea of dating and going out, and it was real convenient that I had that relationship, and it sort of took care of it."]

karol l. jensen, from lesbian epiphanies: women coming out in later life, 1999

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

["When making the transition from heterosexual relationships to relationships with women, there is an entire culture change that can include an aspect of culture shock. Respondent #15, age twenty-eight, recalls that she felt somewhat daunted in the beginning, because she didn't know the rules of the new culture:

I moved right from Jeff's to a relationship with another man. Kevin had been hanging around then too.... and I went to [counseling].... because there was something else going on.... talking about the sexuality piece, but jumped right into this relationship with this man.

[What prompted going into a relationship with Kevin?]

Ah, easier.... I knew what to do. I knew what it meant to be courted, I knew when he was flirting with me. I couldn't figure it out with women. You know through all this time I had been going to [gay club] and [lesbian club] or spending time with the women in my coming-out group, but I never— it was so confusing to me. I didn't know when somebody was flirting. There were no rules. I didn't know if they [women] really liked me. I knew Kevin liked me. He started it."]

karol l. jensen, from lesbian epiphanies: women coming out in later life, 1999

34 notes

·

View notes