#Ágota Kristóf

Text

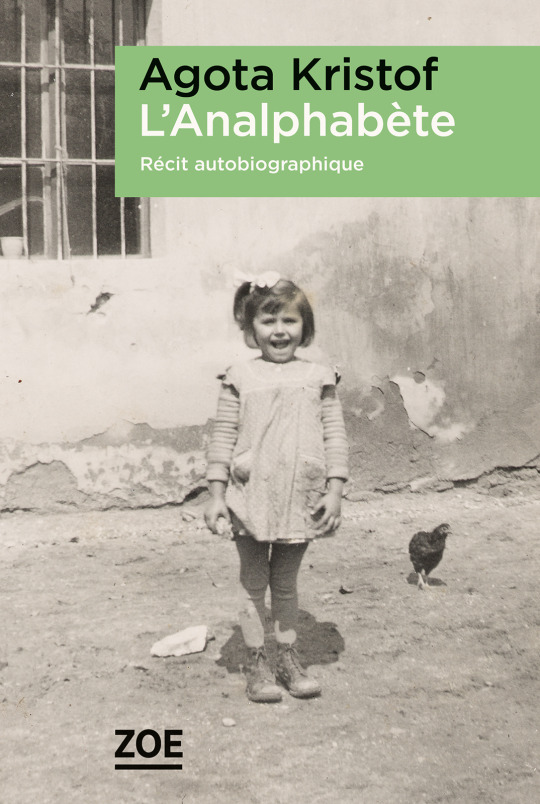

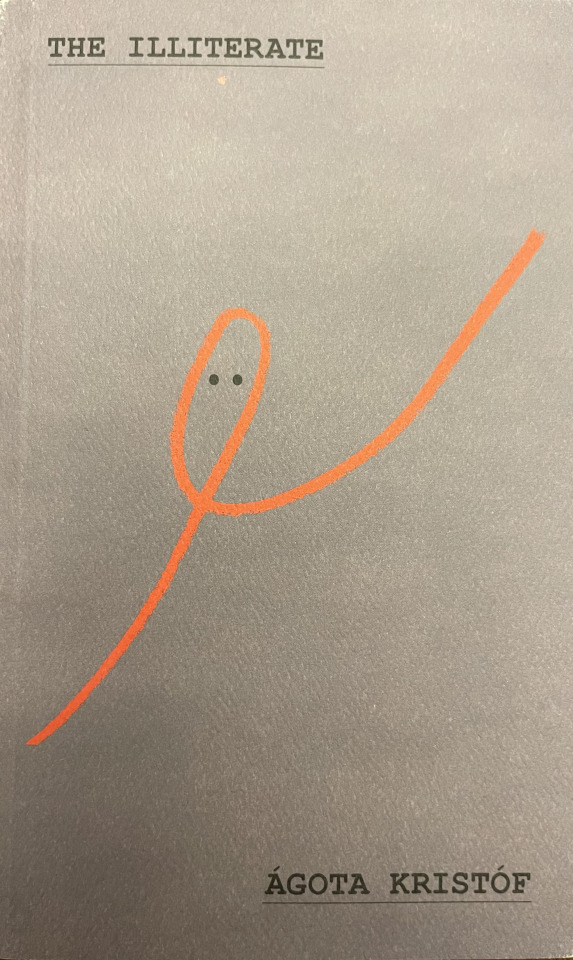

Ágota Kristóf, L'Analphabète. Récit autobiographique, Éditions ZOE, 2004

«Leggo. È come una malattia. Leggo tutto ciò che mi capita sottomano, sotto gli occhi: giornali, libri di testo, manifesti, pezzi di carta trovati per strada, ricette di cucina, libri per bambini. Tutto ciò che è a caratteri di stampa. Ho quattro anni.

[…]

So leggere, so di nuovo leggere. Posso leggere Victor Hugo, Rousseau, Voltaire, Sartre, Camus, Michaux, Francis Ponge, Sade, tutto quello che voglio leggere di francese, e anche gli autori non francesi ma tradotti, Faulkner, Steinbeck, Hemingway. Il mondo è pieno di libri, di libri finalmente comprensibili, anche per me.

[…]

In seguito avrò ancora due figli. […] Quando mi chiedono il significato di una parola, o la sua ortografia, non dico mai "Non lo so". Dico: "Vado a vedere". E vado a vedere nel dizionario, senza stancarmi mai. Divento un'appassionata di dizionari.»

– Ágota Kristóf, (2004), L'analfabeta. Racconto autobiografico, Translation by Letizia Bolzani, «Scrittori», Edizioni Casagrande, Bellinzona, 2011, pp. 7 and 49-50

Cover Art: Ágota Kristóf (5 years old) photographed in Csikvánd, 1940

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ieri era tutto più bello il canto

tra le fronde degli alberi

tra i miei capelli il vento

Ora nevica sulle mie palpebre

il mio corpo

è pesante come roccia

e non c’è motivo di cambiare marciapiede

e non c’è motivo per

andare alle montagne.

Ti aspettavo in fondo alla strada nella pioggia

andavo a capo chino ti vedevo lo stesso

ma non riuscivo a sfiorarti la mano

Ti aspettavo su una panchina le ombre degli alberi

cadevano sulla ghiaia fresca

come anche la tua ombra mentre ti avvicinavi

Ti aspettavo una volta di notte sul monte

crepitavano i rami quando li hai scostati

dal tuo viso e mi hai detto che non potevi restare

Ti aspettavo a riva con l’orecchio incollato

a terra sentivo il tonfo dei tuoi passi

sulla sabbia morbida poi si fece silenzio

Ti aspettavo quando arrivavano i treni lontani

e le persone tornavano tutte a casa

mi hai fatto un cenno da un finestrino il treno non si è fermato

Domani uscirò in strada morti camminano

per queste vie anche io sarò pallida se solo sapessi

dove andare da chi e perché

chiodi

puntuti e smussati

chiudono porte montano grate

tutt’attorno sulle finestre

così si edificano così si edifica

la morte.

Ágota Kristóf, Tr. Fabio Pusterla e Vera Gheno, dalla raccolta di poesie Chiodi

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Pasear al viento es algo que se debe hacer solo, porque hay un tigre y un piano cuya música mata a los pájaros y el miedo solo se puede ahuyentar con el viento, ya se sabe, hace muchísimo tiempo que lo sé.

Kristóf, Á. (1995). Ayer. Editorial Libros del Asteroide.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

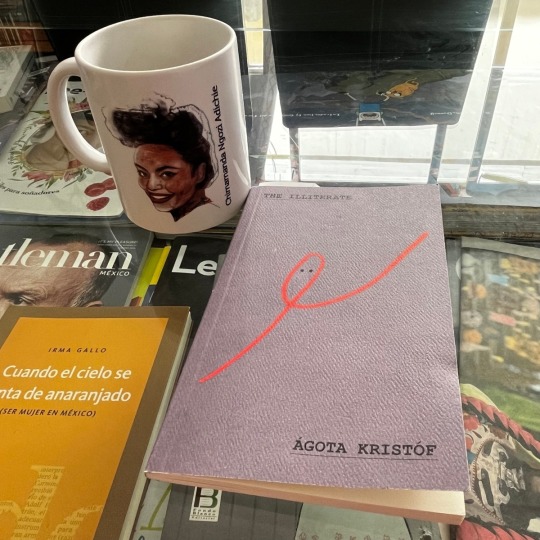

Ágota, una caminata, la soledad y la lengua que no termina de ser mía

Por Irma Gallo

Acababa de cobrar. Todavía no hacía frío pero el calor infernal de mis primeros días en Manhattan ya se había empezado a disolver. Era de noche y quería explorar la ciudad, ahora ya mi ciudad. Fui al Rockefeller Center y descubrí que ahí había una McNally Jackson.

Después de horas y horas de ver libros, muchos de los cuales se me antojaron pero a mi cartera no tanto, a punto de…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Illiterate by Ágota Kristóf, translated by Nina Bogin

From speech to writing

Even as a small child, I like to tell stories. Stories invented by myself.

Sometimes Grandmother comes to visit from the city, to help Mother. In the evening, it is she who puts us to bed. She tries to lull us to sleep with tales we have already heard a hundred times.

I get out of bed and tell Grandmother:

—I'm the one who's going to tell the stories, not you.

She takes me on her knees, rocks me.

—You tell, you tell then.

I begin with a sentence, any sentence, and the rest follows. Characters appear, die, or disappear. There are good characters and evil ones, poor and rich, winners and losers. There is no end to the story I stammer on Grandmother's knees.

—And then . . . and then . . .

Grandmother settles me into my cot, lowers the wick of the petrol lamp and goes out into the kitchen.

My brothers are asleep, I too fall asleep, and in my dream the story continues, beautiful and terrifying.

What I like best is to tell stories to my little brother Tila. He is our mother's favorite. He is three years younger than I am, so he believes everything I say. For example, I lure him into a corner of the garden and ask:

—Do you want me to tell you a secret?

—What secret?

—The secret of your birth.

—There's no secret about my birth.

—Yes, there is. But I'll tell you only if you swear not to tell anybody.

—I swear.

—So this is it—you're a foundling. You're not from our family. You were found in a field, abandoned, completely naked.

Tila says:

—It's not true.

—My parents are going to tell you later, when you're older. If you knew how pitiful you looked, all skinny and naked . . .

Tila starts to cry. I take him in my arms.

—Don't cry. I love you as much as if you were my real brother.

—As much as Yano?

—Almost as much. Yano's my real brother, after all.

Tila thinks for a minute.

—So how come I have the same last name as you? And how come Mother loves me more than you two? You and Yano are always being punished. I'm never punished.

I explain.

—You have the same last name, because you were officially adopted. And Mother is nicer to you than to us because she wants to show that she doesn't make any distinction between you and her real children.

—I am her real child!

Tila screams, he runs towards the house.

—Mama! Mama!

I run after him.

—You swore not to tell. I was just kidding.

Too late. Tila arrives in the kitchen and throws himself into Mother's arms.

—Tell me I'm your son. Your real son. You're my real mother.

I am punished, of course, for telling tales. I kneel down on a corn cob in a corner of the bedroom. Soon Yano arrives with another corn cob and kneels down next to me.

I ask him:

—Why are you being punished?

—I don't know. I just patted Tila on the head and said "I love you, little bastard."

We laugh. I know he tried to get punished on purpose, out of solidarity, and also because he is bored without me.

I tell Tila many other tales, I also try with Yano, but he doesn't believe me because he is one year older than I am.

The desire to write comes later, when the silver thread of childhood is severed, when the bad times arrive, the years when I will say "I don't like them."

When, separated from my parents and my brothers, I leave for boarding school in an unknown city and, in order to bear the pain of separation, only one solution will remain: to write. (pp. 21-23)

***

Displaced persons

From the little Austrian village where we arrived from Hungary, we take the coach for Vienna. The mayor of the village pays for our tickets. During the voyage my little daughter sleeps on my lap. All along the road, luminous mileposts flash by. I have never seen such mileposts before.

When we arrive in Vienna, we go to a police station to announce our presence. There, in the office, I change my baby's diapers and give her her bottle. She throws up. The policemen give us the address of a refugee center and tell us which tramway will take us there for free. In the tram, well-dressed women take my baby on their laps, they slip money into my pocket.

The center is a large building that must have been a factory or a barracks. In immense rooms, straw mattresses are spread out on the floor. There are collective showers and a vast dining hall. At the entrance to the dining hall is a blackboard stuck with notices of missing persons. People are looking for relatives and friends they lost contact with during the border crossing, beforehand or afterwards, in the city of Vienna, or even in the crowd and the chaos of the center.

My husband, like everyone else, spends his days waiting in the offices of different embassies in order to find a host country. I stay with my little daughter who lies on the straw mattress and babbles as she plays with bits of straw. I am obliged to learn a few words of German to ask for what I need for the baby. Taking her in my arms, I enter the center's big kitchen and say to the man who seems to be the manager: "Milch für Kinder, bitte." Or "Seife für Kinder." The man always gives me personally what I ask for.

Christmas is coming when we take the train to Switzerland. There are fir branches decorating the little shelf in front of the window, and chocolate and oranges. This is a special train. Aside from the people accompanying us, the only travellers are Hungarians, and the train makes no stops until the Swiss border. There, a fanfare welcomes us, and kind women hand goblets of hot tea through the window, and chocolate and oranges.

We arrive in Lausanne. We are lodged in a barracks high above the city, next to a soccer field. Young women dressed like soldiers take our children with reassuring smiles. Men and women are separated for the showers. Our clothes are taken away to be disinfected.

Those among us who have already lived through a similar experience confess later on that they have been very frightened. We are all relieved to find each other again afterwards and, above all, to find our children, clean and already well fed. My little girl is sleeping peacefully in a beautiful crib the likes of which she has never had before, next to my bed.

On Sunday, after the soccer game, the spectators come to look at us through the barracks fence. They offer chocolate and oranges, naturally, but also cigarettes and even money. It no longer reminds us of concentration camps, but of a zoo. The more modest among us refrain from going out into the courtyard, while others spend their time reaching their hands through the fence and comparing their bounty.

Several times a week, factory owners come looking for workers. Friends and acquaintances find a job and a flat. They depart, leaving their addresses.

After a month in Lausanne, we spend another month in Zurich, lodged in a school in a forest. We are given language lessons, but I can attend only rarely, because of my little girl.

What would my life have been like if I hadn't left my country? More difficult, poorer, I think, but also less solitary, less torn. Happy, maybe.

What I am certain of is that I would have written, no matter where I was, in no matter what language. (pp. 45-47)

0 notes

Text

Un uomo dice: - Tu chiudi il becco! Le donne non sanno niente della guerra.

La donna dice: - Non sanno niente? Coglione! Abbiamo tutto il lavoro, tutte le preoccupazioni: i bambini da sfamare, i feriti da curare. Voi, una volta finita la guerra siete tutti degli eroi. Morti: eroi. Sopravvissuti: eroi. Mutilati: eroi. E' per questo che avete inventato la guerra, voi uomini. E' la vostra guerra. L'avete voluta voi, fatela allora, eroi dei miei stivali!

Ágota Kristóf - Trilogia della città di K

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ogni tanto ti raddrizzi, e cammini dritto.

Ma io ti amo a notte fonda, quando sei debole, inciampi, ti pieghi.

Ágota Kristóf - La grande ruota

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ágota Kristóf, La grande ruota

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you happen to have any book reccomendations for books with an unreliable narrator and some kind of (sort of) anti-hero? I’ve been curious, but almost all recs are for mystery, murder mystery, or just outright following the direct villain types and I’m considering looking for ones that just look at the ethics of the main character in a limited perspective.

Hi!! Here are some books that come to mind, not sure if they're exactly what you're looking for but worth checking out :) Some of these are probably obvious suggestions but I'm mentioning them just in case. Also anyone reading this, feel free to add on, I'm sure there are many I forgot!

Lolita and Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

Dom Casmurro by Machado de Assis

The Notebook, The Proof, The Third Lie by Ágota Kristóf (I think this one was originally three short novels but in English publication they combined it into one volume)

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

Notes from Underground by Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg

Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner

The Iliac Crest by Cristina Rivera Garza

A few other books that I wouldn't straightforwardly categorize the way you described but might still be of interest (all of them are really excellent imo):

A Personal Matter by Kenzaburō Ōe: Including this one because you mentioned ethics and the narrator is quite pathetic and repulsive, but in a way that's often encouraged (or at least not discouraged) by the society around him.

History of Violence by Édouard Louis: The narrator himself isn't particularly unreliable, but the story’s told through an interesting framing device—he’s listening to his sister recount an attack he survived and mentally noting when he disagrees with how she describes it or characterizes him, so it plays with narrative.

A Hero of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov: Classic multiple narrator/book within a book situation

The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead: The narrator isn't knowingly withholding information from the reader, but there are a bunch of twists and turns that keep you guessing (you discover them as she does.)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sono convinto che ogni essere umano è nato per scrivere un libro, e per nient’altro. Un libro geniale o un libro mediocre, non importa, ma colui che non scriverà niente è un essere perduto, non ha fatto altro che passare sulla terra senza lasciare traccia.

(Ágota Kristóf)

A volte basta anche un diario per lasciare un segno.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nascere

Piangere succhiare bere mangiare dormire aver paura

Amare

Giocare camminare parlare andare avanti ridere

Amare

Imparare scrivere leggere contare

Battersi mentire rubare uccidere

Amare

Pentirsi odiare fuggire ritornare

Danzare cantare sperare

Amare

Alzarsi andare a letto lavorare produrre

Innaffiare piantare mietere cucinare lavare

Stirare pulire partorire

Amare

Allevare educare curare punire baciare

Perdonare guarire angosciarsi aspettare

Amare

Lasciarsi soffrire viaggiare dimenticare

Raggrinzirsi svuotarsi affaticarsi

Morire.

(Ágota Kristóf, “Chiodi”)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ágota Kristóf

Ágota Kristóf, scrittrice e drammaturga ungherese passata alla storia della letteratura mondiale col suo capolavoro La trilogia della città di K. che ha ricevuto numerosi premi letterari ed è stato tradotto in oltre trenta lingue.

I suoi romanzi, dalla scrittura asciutta e incisiva, la prosa austera e la narrazione senza fronzoli, esplorano, in maniera cruda e provocatoria, temi universali come la violenza, la guerra, l’infanzia e la natura umana. I personaggi dei suoi racconti sono spesso segnati dalla condizione esistenziale dell’erranza, di chi è costrettə ad abbandonare la propria terra per cercare rifugio in un paese straniero

Nata il 30 ottobre 1935 a Csikvánd, un piccolo villaggio in Ungheria, a quattordici anni scriveva le sue prime poesie mentre studiava in un collegio di sole ragazze.

Nel 1956, dopo l’intervento dell’Armata Rossa per soffocare la rivolta popolare contro l’invasione sovietica, è fuggita con il marito e la figlia in Svizzera stabilendosi a Neuchâtel, dove ha vissuto fino alla morte, avvenuta il 27 luglio 2011.

Quando è scappata aveva poco più di vent’anni e una bambina di undici mesi avvolta alla schiena. Ha dovuto imparare a ricostruirsi una nuova vita, una nuova lingua, che ha adoperato per scrivere sentendosi sempre analfabeta perché non la padroneggiava abbastanza. Ha lavorato come operaia in una fabbrica, poi è stata insegnante e traduttrice, ha divorziato e avuto altri due figli.

La sua fuga è stato un trauma da cui non si è mai ripresa, allontanata dagli affetti in un mondo totalmente diverso da quello a cui apparteneva. La condizione inesorabile della persona migrante che deve adattarsi a una realtà da cui si sente estranea.

Ha raggiunto il successo internazionale nel 1987, con la pubblicazione de Le grand cahier che, insieme a La preuve e Le troisième mensonge è confluito in quel grande capolavoro che è stato la Trilogie (Trilogia della città di K.). I tre libri ripercorrono il tema del distacco, la separazione di due gemelli, Klaus e Lucas, e il ritrovamento dopo la guerra.

La sua scrittura è scarna, crudele, reale. Un pugno nello stomaco di chi la legge. Quello che racconta non ha bisogno di fronzoli o abbellimenti, è il ritratto di una realtà dura che molto coincide con la sua biografia. Ha rappresentato le tragedie della guerra con una disperazione fredda e sorda, come se scrivesse attraverso gli occhi di un bambino che non giudica mai niente, che si limita a registrare quello che accade con spietata ingenuità.

Vari i romanzi e le opere teatrali che ha scritto consumando, con parole dure, la lotta per integrarsi in una nuova cultura, la continua guerra di chi ha perso la propria terra e non potrà mai più tornare indietro.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Sono convinto, Lucas, che ogni essere umano è nato per scrivere un libro, e per nient’altro. Un libro geniale o un libro mediocre, non importa, ma colui che non scriverà niente è un essere perduto, non ha fatto altro che passare sulla terra senza lasciare traccia»

(Ágota Kristóf, La prova)

“E quando avrai troppa pena, troppo dolore, e se non ne vorrai parlare con nessuno, scrivi.”

( Ágota Kristóf )

.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Düşünüyorum

Şimdilerde umudum çok azaldı. Önceleri arayış içinde durmadan yer değiştiriyordum. Bir şey bekliyordum. Ama ne? Bilmiyordum. Hiçbir fikrim yoktu. Ama hayatın, olduğundan farklı olamayacağını düşünüyordum, yani hayatın adeta hiçbir şey olduğunu. Ama hayat bir şey olmalıydı ve ben o şeyin olmasını bekliyordum, o şeyi arıyordum.

Artık beklenecek bir şey kalmadığını düşünüyorum, bu yüzden odamda kalıyorum, bir sandalyeye oturup hiçbir şey yapmıyorum. Dışarıda bir hayat olduğunu düşünüyorum ama orada da pek bir şey olmuyor. En azından benim için.

Başkaları için belki bir şeyler oluyordur, bu mümkün ama beni ilgilendirmiyor artık.

Buradayım, evimde bir sandalyede oturuyorum. Biraz düş kurar gibiyim. Ne düşleyebilirim? Burada oturuyorum, hepsi bu. İyi olduğumu söyleyemem, rahat etmek için burada duruyor değilim; tam tersine.

Burada oturup durmakla iyi bir şey yapmadığımı biliyorum, sonunda zorunlu olarak kalkmam gerecek, bir süre sonra. Hiçbir şey yapmadan saatlerdir, belki günlerdir oturmaktan ötürü hafif bir fenalık geçiriyorum. Yerimden kalkmak için bir neden bulamıyorum. Ne yapabileceğimi hiç bilmiyorum.

Elbette ortalığı toparlayıp temizlik yapabilirim, evet bu elimden gelir. Evim pis ve bakımsız. En azından yerimden kalkıp pencereyi açmalıyım, içerisi havasız, dumanlı ve kötü kokuyor. Rahatsız olmuyorum ama. Ya da yerimden kalkacak kadar rahatsız olmuyorum diyelim. Bu tür kokulara alışkınım, almıyorum bu kokuları, yalnızca ya çat kapı birisi gelirse diye düşünüyorum…

Oysa o "birisi" yok.

Kimse gelmiyor.

- Ágota Kristóf, Dün

8 notes

·

View notes