#Ian Millhiser

Text

#us politics#republicans#conservatives#twitter#tweet#ian millhiser#gop#us supreme court#justice clarence thomas#justice samuel alito#harlan crow#paul singer#scotus#private jets#billionaires#fuck billionaires#student loans#student loan debt#student loan forgiveness#freeze student debt#student debt forgiveness#2023

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hint for Alito: It's not the coverage, it's the behavior that's putting the court into disrepute.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#vox#america#politics#conservatives#student loans#student loan forgiveness#biden#biden v nebraska#nebraska#ian millhiser#law

0 notes

Photo

(link)

0 notes

Text

Ian Millhiser at Vox:

The Supreme Court announced on Monday that it will not hear Mckesson v. Doe. The decision not to hear Mckesson leaves in place a lower court decision that effectively eliminated the right to organize a mass protest in the states of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

Under that lower court decision, a protest organizer faces potentially ruinous financial consequences if a single attendee at a mass protest commits an illegal act.

It is possible that this outcome will be temporary. The Court did not embrace the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit’s decision attacking the First Amendment right to protest, but it did not reverse it either. That means that, at least for now, the Fifth Circuit’s decision is the law in much of the American South.

For the past several years, the Fifth Circuit has engaged in a crusade against DeRay Mckesson, a prominent figure within the Black Lives Matter movement who organized a protest near a Baton Rouge police station in 2016.

The facts of the Mckesson case are, unfortunately, quite tragic. Mckesson helped organize the Baton Rouge protest following the fatal police shooting of Alton Sterling. During that protest, an unknown individual threw a rock or similar object at a police officer, the plaintiff in the Mckesson case who is identified only as “Officer John Doe.” Sadly, the officer was struck in the face and, according to one court, suffered “injuries to his teeth, jaw, brain, and head.”

Everyone agrees that this rock was not thrown by Mckesson, however. And the Supreme Court held in NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware (1982) that protest leaders cannot be held liable for the violent actions of a protest participant, absent unusual circumstances that are not present in the Mckesson case — such as if Mckesson had “authorized, directed, or ratified” the decision to throw the rock.

Indeed, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor points out in a brief opinion accompanying the Court’s decision not to hear Mckesson, the Court recently reaffirmed the strong First Amendment protections enjoyed by people like Mckesson in Counterman v. Colorado (2023). That decision held that the First Amendment “precludes punishment” for inciting violent action “unless the speaker’s words were ‘intended’ (not just likely) to produce imminent disorder.”

The reason Claiborne protects protest organizers should be obvious. No one who organizes a mass event attended by thousands of people can possibly control the actions of all those attendees, regardless of whether the event is a political protest, a music concert, or the Super Bowl. So, if protest organizers can be sanctioned for the illegal action of any protest attendee, no one in their right mind would ever organize a political protest again.

Indeed, as Fifth Circuit Judge Don Willett, who dissented from his court’s Mckesson decision, warned in one of his dissents, his court’s decision would make protest organizers liable for “the unlawful acts of counter-protesters and agitators.” So, under the Fifth Circuit’s rule, a Ku Klux Klansman could sabotage the Black Lives Matter movement simply by showing up at its protests and throwing stones.

The Fifth Circuit’s Mckesson decision is obviously wrong

Like Mckesson, Claiborne involved a racial justice protest that included some violent participants. In the mid-1960s, the NAACP launched a boycott of white merchants in Claiborne County, Mississippi. At least according to the state supreme court, some participants in this boycott “engaged in acts of physical force and violence against the persons and property of certain customers and prospective customers” of these white businesses.

Indeed, one of the organizers of this boycott did far more to encourage violence than Mckesson is accused of in his case. Charles Evers, a local NAACP leader, allegedly said in a speech to boycott supporters that “if we catch any of you going in any of them racist stores, we’re gonna break your damn neck.”

With SCOTUS refusing to take up McKesson v. Doe, the 5th Circuit's insane anti-1st Amendment ruling that effectively bans mass protests remains in force for the 3 states covered in the 5th: Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

#SCOTUS#Deray McKesson#Protests#Black Lives Matter#5th Circuit Court#Texas#Louisiana#Mississippi#1st Amendment#Counterman v. Colorado#NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware#McKesson v. Doe

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Supreme Court creates train wreck over Texas immigration law.

Over the last forty-eight hours, the Supreme Court has made a monumental mess of its review of a Texas law that seeks to assume control over the US border. If the consequences weren’t tragic, it would be comical.

The Texas law is plainly unconstitutional. It is not even a close question. But the Supreme Court created a situation in which enforcement of that law was stayed and then permitted to go back into effect multiple times in a forty-eighth hour period. It was like the Keystone Cops—all because the Supreme Court does not have the fortitude to control the rogue judges on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Here's the bottom line: As of late Tuesday evening, the Texas law cannot be enforced pending further order of the Fifth Circuit. See NBC News, Appeals court blocks Texas immigration law shortly after Supreme Court action. As explained by NBC,

A three-judge panel of the New Orleans-based 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals split 2-1 in saying in a brief order that the measure, known as SB4, should be blocked. The same court is hearing arguments Wednesday morning on the issue.

The appeals court appeared to be taking the hint from the Supreme Court, which in rejecting an emergency application filed by the Biden administration put the onus on the appeals court to act quickly.

I review the complicated procedural background below with a warning that it may change in the next five minutes. For additional detail, I recommend Ian Millhiser’s explainer in Vox, The Supreme Court’s confusing new border decision, explained.

Let’s start here: The federal government has exclusive authority to control international borders. The Constitution says so, and courts have ruled so for more than 150 years.

There are good reasons for the federal government to control international borders. If individual states impose contradictory regulations on international borders that abut the states, the federal government could not promulgate a single, coherent foreign policy—which is plainly the job of the federal government.

Texas passed a law that granted itself the right to police the southern border and enforce immigration laws, including permitting the arrest and deportation of immigrants in the US who do not have the legal authority to remain in the country.

Mexico immediately notified Texas that it would not accept any immigrants deported by Texas. (Mexico does accept immigrants deported by the US per international agreements.)

A federal district judge in Texas enjoined the enforcement of state law, ruling that it usurped the federal government's constitutional role. Texas appealed.

When a matter is appealed, the court of appeals generally attempts to “maintain the status quo” as it existed between the parties prior to the contested action. Here, maintaining the status quo meant not enforcing the Texas law that allowed Texas to strip the federal government of its constitutional authority over the border.

However, the Fifth Circuit used a bad-faith procedural ploy to suspend the district court’s injunction, thereby allowing Texas law to go into effect. In doing so, the Fifth Circuit did not “maintain the status quo” but instead permitted a radical restructuring of state-federal relations in a way that violated the Constitution and century-and-a-half of judicial precedent.

In a world where the rule of law prevails, the Supreme Court should have slapped down the Fifth Circuit's bad-faith gambit. It did not. Instead, the Supreme Court allowed the Fifth Circuit's bad-faith ploy to remain in effect—but warned the Fifth Circuit that the Supreme Court might, in the future, force the Fifth Circuit to stop playing games with the Constitution.

The debacle is an embarrassment to the Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit. The reason the Fifth Circuit acts like a lawless tribunal is because the Supreme Court has allowed the Fifth Circuit to engage in outrageous, extra-constitutional rulings without so much as a peep of protest from the reactionary majority on the Court.

John Roberts is “the Chief Justice of the United States.” He should start acting like it by reprimanding rogue judges in the Fifth Circuit by name—and referring them to the Judicial Conference for discipline. Until Roberts does that, the Fifth Circuit will do whatever it wants.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#robert b. hubbell#Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter#corrupt SCOTUS#Fifth Circuit#Chief Justice#legal precedent#Nick Anderson#immigration#Texas

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I worry the ‘Biden is old’ coverage is starting to take on the same character as the 2016 But Her Emails coverage – find something that is genuinely suboptimal about the Democratic candidate and dwell on it endlessly to ‘balance’ coverage of the criminal in charge of the GOP.

Ian Millhiser, quoted in The Guardian

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Supreme Court delays Trump 2020 election trial

What happened?

The Supreme Court agreed Wednesday to consider former President Donald Trump's argument he has total legal immunity for any alleged crimes committed in office. That decision delays the federal criminal trial on Trump's efforts to overturn his 2020 loss, plausibly until after the 2024 election.

How we got here

Special counsel Jack Smith filed felony charges against Trump in August, and U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan set a March 5 trial date. The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on Trump's immunity claim the week of April 22. If the court rules against Trump, as expected, pretrial activity — frozen since mid-December — would resume and might last roughly 80 days. That would likely put jury selection in late August to October, barring further delays.

The commentary

This is a "colossal victory for Trump," who openly aims to "delay his trials until after Election Day," then kill them if he wins, Ian Millhiser said at Vox. His appeal needn't take three months, said legal analyst Tristan Snell. "The Supreme Court heard and decided Bush v. Gore in THREE DAYS." It has never been the justice system's job to "save the country from Trump," said Randall Eliason, a George Washington University law professor. "The voters need to do that."

What next?

Trump's New York trial for paying hush money to a porn actress — the only of his four felony cases still on schedule — is set to start March 25.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Twitter has caught on to my work-around for reading Ian Millhiser's tweets without signing up for Twitter and I'm bummed about that.

#this is my only social media platform#it's not loyalty#it's cause my mind is poisoned enough by you yahoos#i don't need to expose myself to the unhinged miscreants of twitter

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Ian Millhiser

Vox

Aug. 3, 2023

The state of Wisconsin does not choose its state legislature in free and fair elections, and it has not done so for a very long time. A new lawsuit, filed just one day after Democrats effectively gained a majority on the state Supreme Court, seeks to change that.

The suit, known as Clarke v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, seeks to reverse gerrymanders that have all-but-guaranteed Republican control of the state legislature — no matter which party Wisconsin voters supported in the last election.

In 2010, the Republican Party had its best performance in any recent federal election, gaining 63 seats in the US House of Representatives and making similar gains in many states. This election occurred right before a redistricting cycle, moreover — the Constitution requires every state to redraw its legislative maps every 10 years — so Republicans used their large majorities in many states to draw aggressive gerrymanders.

Indeed, Wisconsin’s Republican gerrymander is so aggressive that it is practically impossible for Democrats to gain control of the state legislature. In 2018, for example, Democratic state assembly candidates received 54 percent of the popular vote in Wisconsin, but Republicans still won 63 of the assembly’s 99 seats — just three seats short of the two-thirds supermajority Republicans would need to override a gubernatorial veto.

The judiciary, at both the state and federal levels, is complicit in this effort to lock Democrats out of power in Wisconsin. In Rucho v. Common Cause(2019), for example, the US Supreme Court held that no federal court may ever consider a lawsuit challenging a partisan gerrymander, overruling the Court’s previous decision in Davis v. Bandemer (1986).

Three years later, Wisconsin drew new maps which were still very favorable to Republicans, but that included an additional Black-majority district — raising the number of state assembly districts with a Black majority from six to seven. These new maps did not last long, however, because the US Supreme Court struck them down in Wisconsin Legislature v. Wisconsin Elections Commission (2022) due to concerns that these maps may have done too much to increase Black representation.

In response to this US Supreme Court decision, the state Supreme Court, which was then controlled by Republicans, adopted another set of maps proposed by the state’s gerrymandered legislature — maps that had previously been vetoed by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers. As Justice Jill Karofsky wrote in dissent, by implementing the new Republican maps over the governor’s veto, “this court judicially overrides the Governor’s veto, thus nullifying the will of the Wisconsin voters who elected that governor into office.”

Read more.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

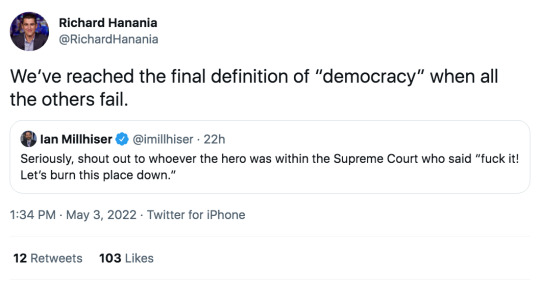

Two events occurred Monday night — one historic, the other rather insignificant — which placed an unflattering spotlight on the Supreme Court of the United States.

The historic event was that Politico published an unprecedented leak of a draft majority opinion, by Justice Samuel Alito, which would overrule Roe v. Wade and permit state lawmakers to ban abortion in its entirety in the US. Alito’s draft opinion is not the Court’s final word on this case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, but the leaked opinion is the latest in a long list of signs that Roe may be in its final days.

The other event that also occurred last night is that I sent two tweets. One praised whoever leaked Alito’s opinion for disrupting an institution that, as I have written about many times in many forums, including my first book, has historically been a malign force within the United States. And a second celebrated the leak for the distrust it might foster in such a malign institution.

Seriously, shout out to whoever the hero was within the Supreme Court who said “fuck it! Let’s burn this place down.”

— Ian Millhiser (@imillhiser) May 3, 2022

…

The fact that someone inside the Court’s very small circle of trust apparently decided to leak a draft opinion is likely to be perceived by the justices, as SCOTUSBlog tweeted out Monday night, as “the gravest, most unforgivable sin.”

To this I say, “good.” If the Court does what Alito proposed in his draft opinion, and overrules Roe v. Wade, that decision will be the culmination of a decades-long effort by Republicans to capture the institution and use it, not just to undercut abortion rights but also to implement an unpopular agenda they cannot implement through the democratic process.

…

This behavior, moreover, is consistent with the history of an institution that once blessed slavery and described Black people as “beings of an inferior order.” It is consistent with the Court’s history of union-busting, of supporting racial segregation, and of upholding concentration camps.

Moreover, while the present Court is unusually conservative, the judiciary as an institution has an inherent conservative bias. Courts have a great deal of power to strike down programs created by elected officials, but little ability to build such programs from the ground up. Thus, when an anti-governmental political movement controls the judiciary, it will likely be able to exploit that control to great effect. But when a more left-leaning movement controls the courts, it is likely to find judicial power to be an ineffective tool.

The Court, in other words, simply does not deserve the reverence it still enjoys in much of American society, and especially from the legal profession. For nearly all of its history, it’s been a reactionary institution, a political one that serves the interests of the already powerful at the expense of the most vulnerable. And it currently appears to be reverting to that historic mean.

…

In Marbury v. Madison (1803), the Supreme Court held that it has the power to strike down federal laws. But the actual issue at stake in Marbury — whether a single individual named to a low-ranking federal job was entitled to that appointment — was insignificant. And, after Marbury, the Court’s power to strike down federal laws lay dormant until the 1850s.

Then came Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), the pro-slavery decision describing Black people as “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Dred Scott, the Court’s very first opinion striking down a significant federal law, went after the Missouri Compromise’s provisions limiting the scope of slavery.

It’s not surprising that an institution made up entirely of elite lawyers, who are immune from political accountability and cannot be fired, tends to protect people who are already powerful and cast a much more skeptical eye on people who are marginalized because of their race, gender, or class. Dred Scott is widely recognized as the worst decision in the Court’s history, but it began a nearly century-long trend of Supreme Court decisions preserving white supremacy and relegating workers into destitution — a history that is glossed over in most American civics classes.

…

The culmination of this age of white supremacist jurisprudence was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which blessed the idea of “separate but equal.” Plessy remained good law for nearly six decades after it was decided.

After decisions like Plessy effectively dismantled the Reconstruction Amendments’ promise of racial equality, the Court spent the next 40 years transforming the 14th Amendment into a bludgeon to be used against labor. This was the age of decisions like Lochner v. New York (1905), which struck down a New York law preventing bakery owners from overworking their workers. It was also the age of decisions like Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923), which struck down minimum wage laws, and Adair v. United States (1908), which prohibited lawmakers from protecting the right to unionize.

The logic of decisions like Lochner is that the 14th Amendment’s language providing that no state may “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” created a “right to contract.” And that this supposed right prohibited the government from invalidating exploitative labor contracts that forced workers to labor for long hours with little pay.

As Alito notes in his draft opinion overruling Roe, the Roe opinion did rely on a similar methodology to Lochner. It found the right to an abortion to also be implicit in the 14th Amendment’s due process clause.

For what it’s worth, I actually find this portion of Alito’s opinion persuasive. I’ve argued that the Roe opinion should have been rooted in the constitutional right to gender equality — what the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg once described as the “opportunity women will have to participate as men’s full partners in the nation’s social, political, and economic life” — and not the extraordinarily vague and easily manipulated language of the due process clause.

…

The Court also did not exactly cover itself in glory after President Franklin Roosevelt filled it with New Dealers who rejected decisions like Lochner and Hammer. One of the most significant Supreme Court decisions of the Roosevelt era, for example, was Korematsu v. United States (1944), the decision holding that Japanese Americans could be forced into concentration camps during World War II, for the sin of having the wrong ancestors.

The point is that decisions like Alito’s draft Dobbs opinion, which would commandeer the bodies of millions of Americans — or decisions dismantling the Voting Rights Act — are entirely consistent with the Court’s history as defender of traditional hierarchies. Alito is not an outlier in the Court’s history. He is quite representative of the justices who came before him.

…

So, to summarize my argument, the judiciary, for reasons laid out by Rosenberg and others, structurally favors conservatives. People who want to dismantle government programs can accomplish far more, when they control the courts, than people who want to build up those programs. And, as the Court’s history shows, when conservatives do control the Court, they use their power to devastating effect.

This alone is a reason for liberals, small-d democrats, large-D Democrats, and marginalized groups more broadly, to take a more critical eye to the courts. And the judiciary’s structural conservatism is augmented by the fact that, in the United States, institutions like the Electoral College and Senate malapportionment give Republicans a huge leg up in the battle for control of the judiciary.

Of course I do not believe that we should literally light the Supreme Court of the United States on fire, but I do believe that diminished public trust in the Court is a good thing. This institution has not served the American people well, and it’s time to start treating it that way.

0 notes

Text

Ian Millhiser at Vox:

The Supreme Court will hear a case later this month that could make life drastically worse for homeless Americans. It also challenges one of the most foundational principles of American criminal law — the rule that someone may not be charged with a crime simply because of who they are.

Six years ago, a federal appeals court held that the Constitution “bars a city from prosecuting people criminally for sleeping outside on public property when those people have no home or other shelter to go to.” Under the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Martin v. Boise, people without permanent shelter could no longer be arrested simply because they are homeless, at least in the nine western states presided over by the Ninth Circuit.

As my colleague Rachel Cohen wrote about a year ago, “much of the fight about how to address homelessness today is, at this point, a fight about Martin.” Dozens of court cases have cited this decision, including federal courts in Virginia, Ohio, Missouri, Florida, Texas, and New York — none of which are in the Ninth Circuit.

Some of the decisions applying Martin have led very prominent Democrats, and institutions led by Democrats, to call upon the Supreme Court to intervene. Both the city of San Francisco and California Gov. Gavin Newsom, for example, filed briefs in that Court complaining about a fairly recent decision that, the city’s brief claims, prevents it from clearing out encampments that “present often-intractable health, safety, and welfare challenges for both the City and the public at large.”

On April 22, the justices will hear oral arguments in City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, one of the many decisions applying Martin — and, at least according to many of its critics, expanding that decision.

Martin arose out of the Supreme Court’s decision in Robinson v. California (1962), which struck down a California law making it a crime to “be addicted to the use of narcotics.” Likening this law to one making “it a criminal offense for a person to be mentally ill, or a leper, or to be afflicted with a venereal disease,” the Court held that the law may not criminalize someone’s “status” as a person with addiction and must instead target some kind of criminal “act.”

Thus, a state may punish “a person for the use of narcotics, for their purchase, sale or possession, or for antisocial or disorderly behavior resulting from their administration.” But, absent any evidence that a suspect actually used illegal drugs within the state of California, the state could not punish someone simply for existing while addicted to a drug.

The Grants Pass case does not involve an explicit ban on existing while homeless, but the Ninth Circuit determined that the city of Grants Pass, Oregon, imposed such tight restrictions on anyone attempting to sleep outdoors that it amounted to an effective ban on being homeless within city limits.

There are very strong arguments that the Ninth Circuit’s Grants Pass decision went too far. As the Biden administration says in its brief to the justices, the Ninth Circuit’s opinion did not adequately distinguish between people facing “involuntary” homelessness and individuals who may have viable housing options. This error likely violates a federal civil procedure rule, which governs when multiple parties with similar legal claims can join together in the same lawsuit.

But the city, somewhat bizarrely, does not raise this error with the Supreme Court. Instead, the city spends the bulk of its brief challenging one of Robinson’s fundamental assumptions: that the Constitution’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishments” limits the government’s ability to “determine what conduct should be a crime.” So the Supreme Court could use this case as a vehicle to overrule Robinson.

That outcome is unlikely, but it would be catastrophic for civil liberties. If the law can criminalize status, rather than only acts, that would mean someone could be arrested for having a disease. A rich community might ban people who do not have a high enough income or net worth from entering it. A state could prohibit anyone with a felony conviction from entering its borders, even if that individual has already served their sentence. It could even potentially target thought crimes.

Imagine, for example, that an individual is suspected of being sexually attracted to children but has never acted on such urges. A state could potentially subject this individual to an intrusive police investigation of their own thoughts, based on the mere suspicion that they are a pedophile.

A more likely outcome, however, is that the Court will drastically roll back Martin or even repudiate it altogether. The Court has long warned that the judiciary is ill suited to solve many problems arising out of poverty. And the current slate of justices is more conservative than any Court since the 1930s.

[...]

The biggest problem with the Ninth Circuit’s decision, briefly explained

The Ninth Circuit determined that people are protected by Robinson only if they are “involuntarily homeless,” a term it defined to describe people who “do not ‘have access to adequate temporary shelter, whether because they have the means to pay for it or because it is realistically available to them for free.’” But, how, exactly, are Grants Pass police supposed to determine whether an individual they find wrapping themselves in a blanket on a park bench is “involuntarily homeless”?

For that matter, what exactly does the word “involuntarily” mean in this context? If a gay teenager runs away from home because his conservative religious parents abuse him and force him to attend conversion therapy sessions, is this teenager’s homelessness voluntary or involuntary? What about a woman who flees her violent husband? Or a person who is unable to keep a job after they become addicted to opioids that were originally prescribed to treat their medical condition?

Suppose that a homeless person could stay at a nearby shelter, but they refuse because another shelter resident violently assaulted them when they stayed there in the past? Or because a laptop that they need to find and keep work was stolen there? What if a mother is allowed to stay at a nearby shelter, but she must abandon her children to do so? What if she must abandon a beloved pet?

The point is that there is no clear line between voluntary and involuntary actions, and each of these questions would have to be litigated to determine whether Robinson applied to an individual’s very specific case. But that’s not what the Ninth Circuit did. Instead, it ruled that Grants Pass cannot enforce its ordinances against “involuntarily homeless” people as a class without doing the difficult work of determining who belongs to this class.

That’s not allowed. While the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure sometimes allow a court to provide relief to a class of individuals, courts may only do so when “there are questions of law or fact common to the class,” and when resolving the claims of a few members of the class would also resolve the entire group’s claims.

The Grants Pass v. Johnson case at SCOTUS could make life worse for unhoused Americans.

#Unhoused People#Homelessness#Grants Pass v. Johnson#SCOTUS#Crime#Martin v. Boise#9th Circuit Court#8th Amendment#Poverty#Grants Pass Oregon

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abortion rights groups have raised concerns that a Donald Trump-nominated federal judge approving an anti-contraception lawsuit is proof the GOP will go further restricting the procedure post Roe v. Wade.

Matthew Kacsmaryk, a judge on the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, recently issued an opinion on the case of Deanda v. Becerra, a lawsuit filed by a Christian father hoping to block the Title X federal program.

In his suit, Alexander Deanda argues that Title X, which approves family planning services be available for anyone, including minors, violates his constitutional right as a parent.

Deanda claims that as he is raising his children as Christians and therefore should "practice abstinence and refrain from sexual intercourse until marriage," Title X violates the direct upbringing of his children.

In his December 8 opinion, Kacsmaryk said that the federal program for birth control does violate Deanda's rights.

While the judge, who was nominated to the bench by Trump in 2017, did not halt the program in his ruling, he allowed both slides to present their arguments for what should happen next.

Deanda's legal team have already signaled they will seek to temporarily shut down Title X while the case is being resolved, potentially putting young people's chance to access contraceptives in limbo while the case is being argued.

The opinion meant Kacsmaryk became the first federal justice to approve a challenge to the right to contraception in the wake of the overturning of Roe V. Wade.

Abortion rights and pro-contraception groups say the ruling is proof fears conservative judges will use the Supreme Court's overturning of the landmark abortion ruling to push forward with further restrictions are coming into fruition.

Alexis McGill Johnson, president and CEO of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, told Newsweek: "Abortion opponents in Texas won't stop with overturning Roe—they are actively working to strip away access to basic health care services and restrict everyone's ability to control their own lives, bodies, and futures. This court's ruling could mean that young people in Texas would no longer be able to get birth control through the Title X family planning program without parental consent, contrary to federal requirements and guidance from American Academy of Pediatrics and others, who support confidential health care services for minors.”

"The ruling could violate long-standing precedent, may have devastating consequences to the health and well-being of young people, and potentially lead to even greater restrictions to health care in the future," McGill Johnson added.

As argued by Vox's Ian Millhiser, who first reported on the decision, Kacsmaryk's ruling will almost certainly be thrown out by either the next appellate court or the Supreme Court as it is "riddled with legal errors."

Millhiser notes that one major issue is that the lawsuit lacks "standing"—evidence that a federal program has harmed the plaintiff in some way.

In his suit, Deanda does not claim that his children are attempting to access contraception via Title X, or even hypothetically planning to, but he is still attempting to block the program from offering contraception to minors without parental consent.

Mini Timmaraju, president of NARAL Pro-Choice America, said that the fact that Kacsmaryk took up the legally and constitutionally unsound case is proof that "anti-choice extremists never intended to stop" with overturning Roe v. Wade.

"They're coming for birth control, in vitro fertilization, and more," Timmaraju told Newsweek.

"This is their long game: Trump's judges are trying to twist the courts in their out-of-touch image for decades to come, and we must do everything in our power to stop them from taking away our fundamental freedoms."

It was the written opinion of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in June for Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, the case that overturned Roe v. Wade's guarantee of access to abortion, which sparked concerns from Democrats and pro-abortion groups that conservatives will go further.

Thomas wrote that after voting to overturn Roe v. Wade, the court now has a "duty" to review all the Supreme Court's due process precedents.

Thomas named three cases as examples of where SCOTUS could "correct the error": Obergefell v. Hodges, which established the right to same-sex marriage in 2015, Lawrence v. Texas, which struck down laws that made sodomy illegal in 2003, and Griswold v. Connecticut, which allows married couples a legal right to buy and use contraceptives.

In July, one month after Roe v. Wade was overturned, the House passed the Right to Contraception Act, which would grant Americans a federal right to obtain and use birth control and contraception.

The bill cleared the House in a 228 to 195 vote, with all those who objected to the bill being Republicans.

Rep. Kat Cammack (R-FL), a co-chair of the Congressional Pro-Life Caucus, argued on the House floor that the bill was "completely unnecessary" and the right to contraception is not at risk.

"The liberal majority is clearly trying to stoke fears and mislead the American people once again because in their minds stoking fear clearly is the only way that they can win," Cammack said.

Following the vote, Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-NY) tweeted: "Make no mistake: Republicans & the far-right majority on the Supreme Court will take every opportunity to undermine—or overturn—the right to access birth control."

#us politics#news#newsweek#2022#trump administration#republicans#conservatives#gop#Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk#texas#Deanda v. Becerra#Title X#contraceptive bans#Alexander Deanda#family planning#radical christianity#conservative christianity#roe v. wade#dobbs v. jackson women’s health organization#Alexis McGill Johnson#Planned Parenthood Federation of America#lawrence v. texas#griswold v. connecticut#Ian Millhiser#Mini Timmaraju#NARAL Pro-Choice America#Right to Contraception Act#Rep. Jerry Nadler#Rep. Kat Cammack

8 notes

·

View notes