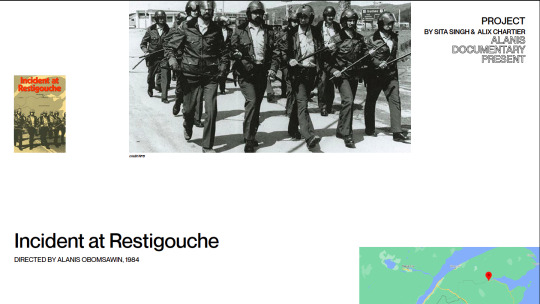

#Incident at Restigouche

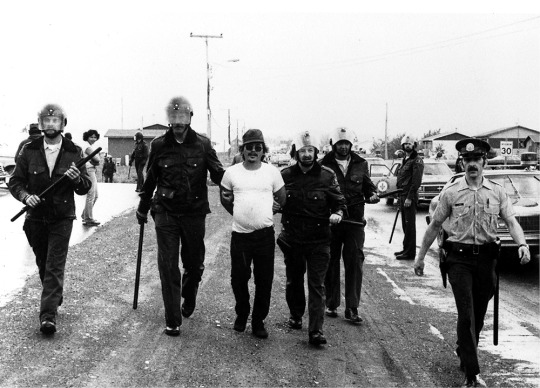

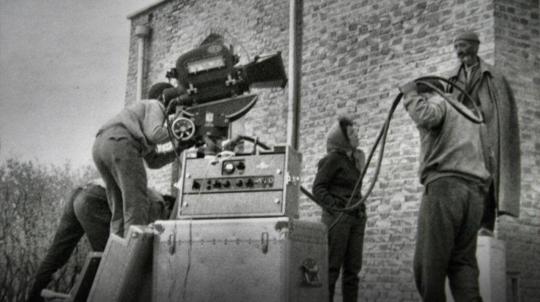

Photo

On this day, 11 June 1981, the first of two violent raids by Québec police took place on the Listuguj (Restigouche) reserve of the Miꞌgmaq First Nations people. Officers in full riot gear attacked the reserve, while 35 boatloads of game wardens came ashore to shut down fishing by Mi'gmaq people. During the first raid police seized 100 fishing nets, arrested nine people and was accused of brutally beating others, like fisherman Randy Morrison, who reportedly stated: "I was trying to get out of the way of a group of policemen. A group of them grabbed, handcuffed, and then beat me with their sticks." On June 20, police returned, blockading the area and firing rubber bullets and tear gas. While the government claimed to be acting for conservation reasons, at the same time as shutting down salmon fishing by First Nations people, increasing oil exploration on Indigenous land was continuing apace. At the time there was speculation that the raids were to assert Québec's control of salmon fishing as a precursor to potential independence. Clashes continued in the aftermath of the raids, with two Indigenous people shot by police and another reserve raided by a mob of white Canadians who destroyed a Native salmon net. The second raids were filmed in a landmark documentary by Indigenous director Alanis Obomsawin in her film, Incident at Restigouche. Learn about Indigenous genocide and resistance in the Americas in this book: https://shop.workingclasshistory.com/products/500-years-of-indigenous-resistance-gord-hill https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=642632851243267&set=a.602588028581083&type=3

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

At Ninety-One, Alanis Obomsawin Is Not Ready to Put Down Her Camera

She revolutionized cinema and is inspiring the next generation of Indigenous filmmakers

Until a few years ago, the National Film Board was headquartered in a sprawling suburban complex off a Montreal highway. In 2019, it moved into its new downtown space, a slick thirteen-storey building designed with Obomsawin in mind. In a reception room on the main floor, a recording of an interview with her plays on loop. On the second floor is the 138-seat Alanis Obomsawin Theatre. A few floors above, a still from Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance covers the wall of a conference room. If her work and image are part of the building’s DNA, it’s because she has become, as Wente puts it, the raison d’être of Canada’s public film producer and distributor. “If you were to ask me why the NFB should exist,” Wente tells me, “she’s why. She’s who I would point to.”

Read more at thewalrus.ca.

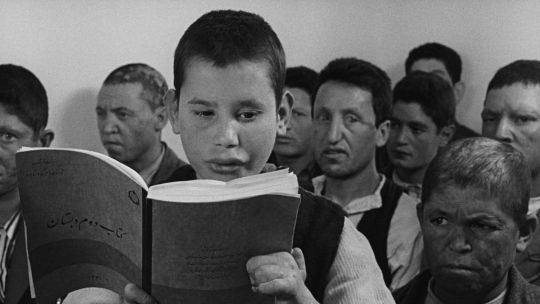

Stills and photography from When All the Leaves Are Gone (2010), Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), and Incident at Restigouche (1984), courtesy of the National Film Board

#Film#Documentary#Indigenous#Alanis Obomsawin#Directed by women#Photography#September/October 2023#Zoe Heaps Tennant

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

La première québécoise de ᑕᐅᑐᒃᑕᕗᒃ Tautuktavuk (Sous nos yeux) un film primé de Lucy Tulugarjuk et Carol Kunnuk – le lundi 11 décembre 2023 à 19h

Isuma Productions, Isuma Distribution International et Kingulliit Productions,en collaboration avec Cinema Politica, ont le plaisir d’annoncer que le long métrage dramatique primé TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX), coréalisé par Lucy Tulugarjuk (Tia and Piujuq, One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, Atanarjuat : The Fast Runner) et Carol Kunnuk (Welcome to my Qammaq, Being Prepared, Attagatuluk), sera présenté en première québécoise comme film de clôture de la saison d’automne de Cinema Politica Concordia le lundi 11 décembre 2023 à 19h à l’Université Concordia (salle H-110).

La première québécoise sera suivie d’une séance de questions et réponses et d’une conversation avec Lucy Tulugarjuk et la documentariste Alanis Obomsawin (Incident at Restigouche, Kanehsatake : 270 Years of Resistance, Our People Will Be Healed). La table ronde sera animée par l’artiste multidisciplinaire, cinéaste et conservateur d’art Asinnajaq (Upinnaqusittik, Three Thousand). Tous les détails sont disponibles ici.

TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX) a été présenté en première mondiale au Festival international du film de Toronto (TIFF) en septembre 2023, où il a remporté le prix Amplify Voices BIPOC & Canadian First Feature Award, ainsi que le Sun Jury Award au 2023 ImagineNATIVE Film Festival.

Après sa première québécoise au Cinema Politica, TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX) sortira en salle à Montréal le 12 janvier 2024, avec des projections du film sous-titré en français et en anglais au Cinéma Moderne.Ce film inuit contemplatif, à la fois provocateur et subtilement intersectionnel, explore les points de convergence entre les mesures pandémiques, la violence domestique, la famille et les traumatismes intergénérationnels. Brouillant la frontière entre fiction et non-fiction, après un événement traumatisant, Uyarak et sa sœur aînée Saqpinak entreprennent un difficile voyage de guérison qui leur rappelle l’importance de la communauté, de la culture et de la famille. TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX) explore les questions de violence domestique et de toxicomanie du point de vue de deux femmes inuites.

0 notes

Text

Indigenous Resistance Through Film

Obomsawin reimages Indigeneity through the medium of filmmaking. Following the lives of Indigenous people across “Canada,” and taking a particular interest in their struggle for sovereignty and state recognition, Obomsawin renegotiates the objective, omnipotent presence of the documentary filmmaker and rather positions herself within the struggle, centering Indigenous culture, history, and experiences as the argument, evidence, and conclusion of her films. Therefore, her work contests twofold; firstly the ways in which documentary filmmaking as a medium has been used in the colonial sense to control public perception/understanding of a certain event, people, or history, and secondly, the subject matter of her films — seminal Indigenous issues and events in Canada — expose the continuous colonial violence that is enacted upon by all levels of government towards Indigenous people, whilst challenging official histories and narratives about Canada’s relationship with Indigenous people. Her films continue to see what the rest of the county cannot see, or chooses to ignore.

Obomsawin’s filmmaking practice begins with listening. Often, before any second that is caught on camera, she will go into the community that she is working with alone, without a crew or a camera, and engage in conversation and daily life. She insists on building relationships and connections first, attentive to witnessing before any act of producing. Her participatory style of filmmaking adapts the didactic documentary tradition. Obomsawin appears in all of her films, seated in homes interviewing subjects, engaging with children in schools, or barricaded behind the lines during a resistance. You will often hear her voice encouraging subjects during interviews, or laughing with a group. Her presence throughout the films reminds viewers of her intimate, intrinsic connection to the subject matter — as an Indigenous woman she is just as much shaped and informed by the events, communities, and histories that she documents.

The subject matter of Obomsawin’s films speak to the ongoing effects of settler colonialism, genocide, persecution, and state surveillance of Indigenous people. Incident at Restigouche (1984) follows the raids on the Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation by the Quebec provincial police, as an effort of imposing restrictions on their fishing rights, Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986) is a devastating examination of Canada's child welfare system in regards to the (mis)treatment of Indigenous children and youth, and the harm that the system causes. Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), her first feature-length film, is filmed at a residential school in northern Ontario around Christmas time, Hi-Ho Mistahey! (2013) follows the campaign Shannen’s Dream, which lobbies for improved educational opportunities for Indigenous youth, and examines the on-going impacts of the lack of proper education for Indigenous youth, and Our People Will Be Healed (2017) profiles the Helen Betty Osborne Ininiw Education Resource Centre in Norway House Cree Nation, the structure of the school, offering a vision for what Indigenous based education could look like in the future, whilst recognizing the challenges the school is facing today.

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) documents the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance/Oka Crisis and is the most well known of Obomsawin’s films. Had it not been for Obomsawin and her crew documenting 250 hours worth of footage behind the barricade, in standoff with the military, and at the end of resistance, the public memory of this event would have been shaped solely by one-sided government press releases, limited CBC reporting, and Prime Minister Mulroney asserting that the Mohawk warriors were dangerous criminals with illegal weapons. Emotive, intense moments behind the barricade, articulated through interviews with individual Mohawk warriors, offer a closer account of the events instead. Obomsawin’s uncompromising and partisan view of what occurred at the Oka golf course gave way for Mohawk historical narratives to be re-articulated and Indigenous efforts for self-determination to be legitimised.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ex-Tory MP Bernard Valcourt pleads not guilty to obstructing, resisting police

Former federal Conservative cabinet minister Bernard Valcourt has pleaded not guilty to obstructing and resisting police.

Valcourt, 71, is accused of allegedly obstructing the work of two police officers on Oct. 4 in Edmundston, N.B., located in the province's northwest, by the Maine border.

Little information is included in court documents about the incident involving Valcourt, who served as a New Brunswick MP in the governments of Brian Mulroney, Kim Campbell and Stephen Harper. He was also a member of New Brunswick's legislature.

Valcourt's lawyer, Basile Chiasson, says his client pleaded not guilty in Edmundston court earlier this week, adding that he had no further comment.

Chiasson says that since his client is well-known in the region, the case was transferred to a Quebec prosecutor, and a judge from outside the Edmundston area will preside over the proceedings.

The former MP for Madawaska--Restigouche held several government roles, including minister of Aboriginal affairs and northern development. He was defeated in the 2015 election.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published March 1, 2023.

from CTV News - Atlantic https://ift.tt/IafL4Vd

0 notes

Text

Here are a few classic movies available online for free on the Canadian National Film Board website:

Neighbours (1952) Norman McLaren

Speak White (1960) Pierre Falardeau & Julien Poulain

The Steak (1993) Pierre Falardeau & Manon Leriche

Kanasetake, 270 years of Resistance (1991) Alanis Obomsawin

Incident at Restigouche (1984) Alanis Obomsawin

Acadia Acadia?!? (1971) Pierre Perreault & Michel Brault

Comfort and Indifference (1991) Denis Arcand

The Sand Castle (1977) Co Hoedman

The Railrodder [staring Buster Keaton] (1965) Gerald Potterton

#Speak White is in french only but all the others have english and subtitles options#anyway these are all amazing get into it!!!!#i would also say go watch everything Brault and Perreault did#Without michel brault there is no New Wave and there is no Éclair shoulder camera#so basically no Faces 1968 by john cassavetes. you see where im going here#canadian cinema#quebec cinema#norman mclaren#pierre falardeau#julien poulain#manon leriche#alanis obomsawin#pierre perrault#michel brault#denis arcand#co hoedman#gerald potterton#buster keaton

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sculpting in Time.

As the world inches into the future, we invited Justine Smith, author of the ‘100 Films to Watch to Expand your Horizons’ list, to look to the cinematic past to help us process the present.

It is said that the essential quality of cinema that distinguishes it from other arts is time. Music can be played at different tempos, and standing in a museum, we choose how many seconds or hours we stand before a great painting. A novel can be savored or sped through. Cinema, on the other hand, exists on a fixed timeline. While it can theoretically be experienced at double or half speeds, it is never intended to be seen as such. Cinema’s fundamental quality is experiencing time on someone else’s terms. As the great Andrei Tarkovsky said in describing his work as a filmmaker, he was “sculpting in time”.

The perception of time, however, is not universal. Our moods, our emotions, and our ideologies shape our relationship to it. Most Western audiences are further acclimated to Western cinema’s ebbs and flows, which similarly favor efficiency and invisibility. When we see a Hollywood film, we don’t want the story to stop. We want to be swept away and forget that we are all moving towards a mortal endpoint. Cinema, though, in its infinite possibilities, exists far beyond these parameters. It can challenge and enrich our vision of the world. If we open ourselves up, we can transfigure and transform our relationship to time itself.

When I first put together my 100 Films to Watch to Expand your Horizons list, I did it quite haphazardly. I imagined countries, filmmakers and experiences that I felt went under-appreciated in discussions of cinema’s potential. Intuitively, I went searching for corners of experience that expanded my own cinematic horizon. Some of these films are well-loved and seen by wide audiences; others are virtually unknown. It was often only after the fact that the myriad of intimate connections between the films came to light.

Manuel de Oliveira’s ‘Visit, or Memories and Confessions’ (2015).

“The only eternal moment is the present.” —Manoel de Oliveira

Released in 2015 but made in 1982, Visit, or Memories and Confessions is a reflection on life, cinema and oppression by Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira. If we were to reflect on cinema’s history, few filmmakers have the breadth of experience and foresight as Oliveira. His first film was made in the silent era using a hand-cranked camera. By the time of his death at 106 years of age, he had made dozens of movies, including many in a digital format.

He made Visit, or Memories and Confessions in the shadow of the Portuguese dictatorship. While filming, he imagined he was in the twilight of his life. It revisited essential incidents in his history but also that of his country. It’s a film of reconciliation, violence and oppression, told tenderly in a home lost as a consequence of a vindictive dictatorship. Oliveira’s film, like his life, spanned time in a way that stretches perceptions. It’s a film without significant incident, about the peaceful pleasures and tragedies of daily life.

Elia Suleiman’s ‘The Time that Remains’ (2009).

What worlds have changed over the past one hundred years? The same breadth of perception, which often feels too seismic to tackle in traditional narrative cinema, was also explored in The Time that Remains. In a retelling of his family’s history, Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman also tells Israel’s story. It is a film of wry comparisons and Keatonesque comic patterns. As borders change and time passes, few things fundamentally change, except on a spiritual plane. What happens to people without an identity or a country? What damage does it do to their souls?

The question of time looms heavily in both Oliveira’s and Suleiman’s films. They are movies that contemplate centuries of experiences and explore how those stories are guarded, twisted and erased by the powerful.

Alanis Obomsawin’s ‘Incident at Restigouche’ (1984).

The echoes of history and attempts to break with old patterns often emerge in other anti-colonial and anti-imperialist films. They can be seen in Alanis Obomsawin’s vital and angry Incident at Restigouche, about an explosive, centuries-in-the-making 1981 conflict between Quebec provincial police and the First Nations people of the Restigouche reserve; In Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India, villagers must win a cricket match to free themselves from involuntary servitude; and in Daughters of the Dust, the languid pace of the Gullah culture is challenged by the promise and violence of the American mainland.

Time, more than just a tool for chronology, becomes in itself a tool for oppression. Those who control time maintain power. If we are to break with dominant histories, the rhythms of oppression must be broken and challenged.

Forugh Farrokhzad’s ‘The House is Black’ (1963).

“The universe is pregnant with inertia and has given birth to time.” —Forugh Farrokhzad, The House is Black

Persian filmmaker and poet Forugh Farrokhzad made just one film before her untimely death in a car accident when she was 32. The House is Black is a short documentary about a Leper colony, which utilizes essay-esque prose taken from the Quaran, and Farrokhzad’s poetry. It is a film about people who are seen as invisible by society at large, cast away and hidden. The film reflects on beauty, sickness and reconciliation. How does one experience time when you’ve been ostracized and cut off from the larger world?

Barbara Loden’s landmark independent film Wanda asks a similar question. A solo mother who cycles from one abusive situation to the next exists outside of time and space. She is invisible. If we look at most American cinema, it might as well be propelled by people who take control over their destiny, but what of the people who are (un)willingly passive to the whims of society and other human beings? In her powerlessness, Wanda stands in for the invisible labor and sacrifices of so many other women. The ordinariness of Wanda’s life, the dusty and dirty environments she inhabits, rebound with significance. It is, however, not a victorious film. Instead, it is a profound portrait of loss and beauty. It’s the only film Barbara Loden ever made.

"If you don't want anything you won't have anything, and if you don't have anything, you're as good as dead." —Norman Dennis in Wanda

Barbara Loden’s ‘Wanda’ (1970).

In 2020, it seemed all we had was time. What seemed like an opportunity quickly became horrific. Time became a burden. We were reminded of our finite time on this Earth and all the hours spent commuting, working and surviving. The pandemic has had a seismic impact on our perceptions. In processing the ongoing crisis, we’ve transformed our relationship to the passage of time. We’ve altered the state of our reality.

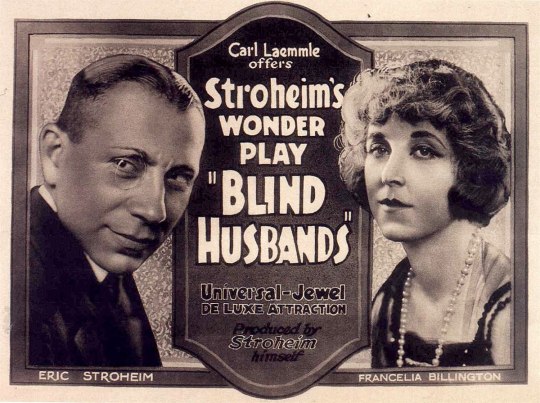

This new pandemic gaze offers us new perspectives on time and history. The oldest film on the list is Erich Von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands, released in 1919 during the grips of the Spanish flu. The film does not reference the event, but its sensuality and class conflicts speak to a world on the brink of seismic change. It is a movie about an Austrian military officer who seduces a surgeon’s wife. The men grapple with jealousy and violence on a literal mountaintop, fighting for survival in an increasingly mechanized society.

Poster for Erich Von Stroheim’s ‘Blind Husbands’ (1919).

To this day, Blind Husbands is shocking. It’s profoundly fetishistic and loaded with heavy sexual imagery. It’s a movie about touch and desire absent of love and affection. It speaks to aspects of current life that feel lost and impenetrable. It speaks to growing and changing social disparities as well. Surviving the modern world is more than just surviving the plague; it has to do with value compromises and shifting power dynamics.

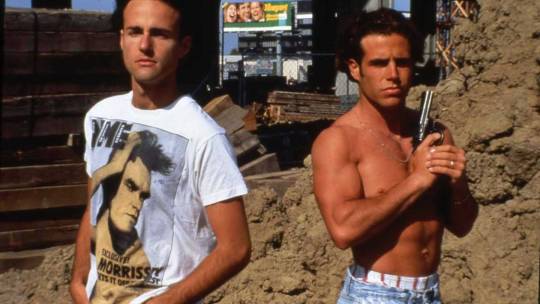

But, a pandemic is also about loss. Gregg Araki’s 1992 film The Living End explores the AIDS crisis from the inside out. Rebellious and angry, the film is about a gay hustler and a movie critic, both of whom have been diagnosed with the HIV virus. With characters who are cast out from society at large, gripped with a deadly and unknown fate, The Living End is apocalyptic—much like other Araki works from the 90s, such as The Doom Generation and Totally Fucked Up. It captures the deep sense of hopelessness of experiencing a pandemic while also belonging to a marginalized group. What is so radical about Araki’s cinema, though, is that it is also fun. It is a film that transcends mourning and becomes a lavish punk celebration. It is a film about survival, out of step with dominant ideology and histories.

Gregg Araki's ‘The Living End’ (1992).

The connections between Blind Husbands and The Living End bridge together to form common passions and changing perceptions. Both films are products of their time, at once part of distant histories but also uncomfortably prescient. More than films about a specific time and place, they are transformed by the time we live in now. To watch and connect with these movies in a pandemic means looking and living beyond the current moment.

While it seems like cinema might be facing an especially precarious future, it feels like the ideal art form to process what is happening right now. Caught in the vicious patterns of our own creation, giving ourselves up to the rhythms of someone else’s will might be a necessary form of healing, as well as an ongoing project in compassion. Time does not have to be a prison; it can be an agent for liberation.

Related content

100 Films to Watch to Expand Your Horizons

The Oxford History of World Cinema

1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

The Great Unknown: High Rated Movies with Few Views

Follow Justine on Letterboxd

#justine smith#justine peres smith#world cinema#expand your horizons#gregg araki#manoel de oliveira#elia suleiman#julie dash#alanis obomsawin#Forugh Farrokhzad#barbara loden#erich von stroheim#mubi#criterion#criterion collection#letterboxd

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

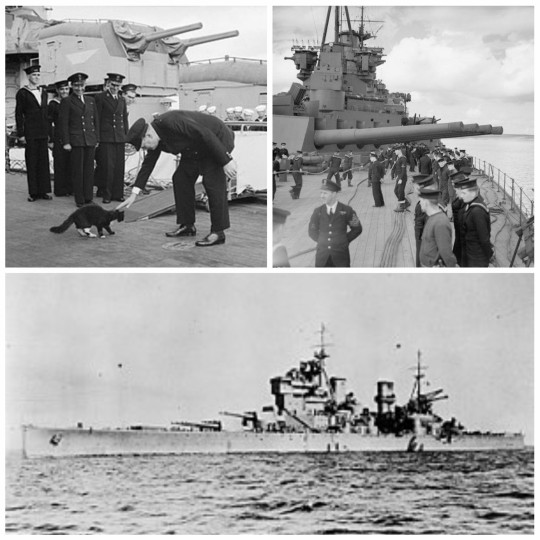

• HMS Prince of Wales

HMS Prince of Wales was a King George V-class battleship of the British Royal Navy. She had an extensive battle history, first seeing action in August 1940 while in her drydock when she was attacked by German aircraft.

In the aftermath of the First World War, the Washington Naval Treaty was drawn up in 1922 in an effort to stop an arms race developing between Britain, Japan, France, Italy and the United States. This treaty limited the number of ships each nation was allowed to build, and capped the tonnage of all capital ships at 35,000 tons. These restrictions were extended in 1930 through the Treaty of London, however, by the mid-1930s Japan and Italy had withdrawn from both of these treaties, and the British became concerned about a lack of modern battleships within their navy. As a result, the Admiralty ordered the construction of a new battleship class: the King George V class.

The main armament of the class was limited to the 14-inch (356 mm) guns prescribed under these instruments. They were the only battleships built at that time to adhere to the treaty, and even though it soon became apparent to the British that the other signatories to the treaty were ignoring its requirements, it was too late to change the design of the class before they were laid down in 1937. Prince of Wales was originally named King Edward VIII but upon his abdication the ship was renamed before she had been laid down. This occurred at Cammell Laird's shipyard in Birkenhead on January 1st, 1937, although it was not until May 3rd, 1939 that she was launched. She was still fitting out when war was declared in September, causing her construction schedule, and that of her sister, King George V, to be accelerated. During early August 1940, while she was still being outfitted and was in a semi-complete state, Prince of Wales was attacked by German aircraft. One bomb fell between the ship and a wet basin wall, narrowly missing a 100-ton dockside crane, and exploded underwater below the bilge keel. Buckling of the shell plating took place over a distance of 20 to 30 feet (9.1 m), rivets were sprung and considerable flooding took place in the port outboard compartments in the area of damage, causing a ten-degree port list. The flooding was severe, due to the fact that final compartment air tests had not yet been made and the ship did not have her pumping system in operation. The water was pumped out through the joint efforts of a local fire company and the shipyard, and Prince of Wales was later dry docked for permanent repairs. This damage and the problem with the delivery of her main guns and turrets delayed her completion. As the war progressed there was an urgent need for capital ships, and so her completion was advanced by postponing compartment air tests, ventilation tests and a thorough testing of her bilge and fuel oil systems.

She was powered by Parsons geared steam turbines, driving four propeller shafts. Steam was provided by eight Admiralty boilers which normally delivered 100,000 shaft horsepower (75,000 kW). This gave Prince of Wales a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). She also carried 180 long tons (200 t) of diesel oil, 256 long tons (300 t) of reserve feed water and 444 long tons (500 t) of freshwater. Prince of Wales had a range of 3,100 nautical miles (5,700 km; 3,600 mi) at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph). Prince of Wales mounted 10 BL 14-inch (356 mm) Mk VII guns. The 14-inch guns were mounted in one Mark II twin turret forward and two Mark III quadruple turrets, one forward and one aft. The secondary armament consisted of 16 QF 5.25-inch (133 mm) Mk I guns which were mounted in eight twin mounts, weighing 81 tons each. Along with her main and secondary batteries, Prince of Wales carried 32 QF 2 pdr (1.575-inch, 40.0 mm) Mk.VIII "pom-pom" anti-aircraft guns. She also carried 80 UP projectors, which were short range rocket firing anti-aircraft weapons used extensively in the early days of the Second World War.

On May 22nd, 1941, Prince of Wales, the battlecruiser Hood and six destroyers were ordered to take station south of Iceland and intercept the German battleship Bismarck if she attempted to break out into the Atlantic. Captain John Leach knew that main-battery breakdowns were likely to occur, since Vickers-Armstrongs technicians had already corrected some that took place during training exercises in Scapa Flow. The next day Bismarck, in company with the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, was reported heading south-westward in the Denmark Strait. At 20:00 Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland, in his flagship Hood, ordered the force to steam at 27 knots (50 km/h), which it did most of the night. His battle plan called for Prince of Wales and Hood to concentrate on Bismarck, while the cruisers Norfolk and Suffolk would handle Prinz Eugen. However the two cruisers were not informed of this plan because of strict radio silence. At 02:00, on 24 May, the destroyers were sent as a screen to search for the German ships to the north. At 05:37 an enemy contact report was made, and course was changed to starboard to close range. Neither ship was in good fighting trim. Hood, designed twenty-five years earlier, lacked adequate decking armour and would have to close the range quickly, as she would become progressively less vulnerable to plunging shellfire at shorter ranges. She had completed an overhaul in March and her crew had not been adequately retrained. Prince of Wales, with thicker armour, was less vulnerable to 15-inch shells at ranges greater than 17,000 feet (5,200 m), but her crew had also not been trained to battle efficiency.

At 05:53, despite seas breaking over the bows, Prince of Wales opened fire on Bismarck at 26,500 yards (24,200 m). There was some confusion among the British as to which ship was Bismarck and thirty seconds earlier Hood had mistakenly opened fire on Prinz Eugen as the German ships had similar profiles. Hood's first salvo straddled the enemy ship, but Prinz Eugen, in less than three minutes, scored 8-inch-shell hits on Hood. The first shots by Prince of Wales two three-gun salvoes at ten second intervals were 1,000 yards over. The sixth, ninth and thirteenth salvos were straddles and two hits were made on Bismarck. One shell holed her bow and caused Bismarck to lose 1,000 tons of fuel oil, mostly to salt-water contamination. The other fell short, and entered Bismarck below her side armour belt, the shell exploded and flooded the auxiliary boiler machinery room and forced the shutdown of two boilers due to a slow leak in the boiler room. Both German ships initially concentrated their fire on Hood and destroyed her with salvoes of 8- and 15-inch shells. Prince of Wales fired unopposed until she began a port turn at 05:57, when Prinz Eugen took her under fire. After Hood exploded at 06:01, the Germans opened intense and accurate fire on Prince of Wales, with 15-inch, 8-inch and 5.9-inch guns. A heavy hit was sustained below the waterline as Prince of Wales manoeuvred through the wreckage of Hood. At 06:02, a 15-inch shell struck the starboard side of the compass platform and killed the majority of the personnel there.

At 06:05 Captain Leach decided to disengage and laid down a heavy smokescreen to cover Prince of Wales's escape. Following this, Leach radioed the Norfolk that Hood had been sunk and then proceeded to join Suffolk roughly 15 to 17 miles (24 to 27 km) astern of Bismarck. Throughout the day the British ships continued to chase Bismarck until at 18:16 when Suffolk sighted the German battleship at 22,000 yards (20,000 m). Prince of Wales then opened fire on Bismarck at an extreme range of 30,300 yards (27,700 m), she fired 12 salvos but all of them missed. After losing Bismarck owing to poor visibility and after searching for 12 hours, Prince of Wales headed for Iceland and took no further part in actions against Bismarck.

Following repairs at Rosyth, Prince of Wales transported Prime Minister Winston Churchill across the Atlantic for a secret conference with US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. On August 5th, Roosevelt boarded the cruiser USS Augusta from the presidential yacht Potomac. Augusta proceeded from Massachusetts to Placentia Bay and Argentia in Newfoundland with the cruiser USS Tuscaloosa and five destroyers, arriving on August 7th. On August 9th, Churchill arrived in the bay aboard Prince of Wales, escorted by the destroyers HMS Ripley, HMCS Assiniboine and HMCS Restigouche. At Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, Roosevelt transferred to the destroyer USS McDougal to meet Churchill on board Prince of Wales. The conference continued from 10 to 12 August aboard the heavy cruiser USS Augusta and, at the end of the conference, the Atlantic Charter was proclaimed.

In September 1941, Prince of Wales was assigned to Force H, in the Mediterranean. On September 24th, Prince of Wales formed part of Group II, led by Vice-Admiral Alban Curteis. The force provided an escort for Operation Halberd, a supply convoy from Gibraltar to Malta. On September 27th, the convoy was attacked by Italian aircraft, with Prince of Wales shooting down several with her 5.25-inch (133 mm) guns. Later that day there were reports that units of the Italian Fleet were approaching. Prince of Wales, the battleship Rodney and the aircraft carrier Ark Royal were despatched to intercept, but the search proved fruitless. The convoy arrived in Malta without further incident, and Prince of Wales returned to Gibraltar.

On October 25th, Prince of Wales and a destroyer escort left home waters bound for Singapore, there to rendezvous with the battlecruiser Repulse and the aircraft carrier Indomitable. Indomitable however ran aground off Jamaica a few days later and was unable to proceed. Prince of Wales reached Colombo, Ceylon, on November 28th, joining Repulse the next day. On December 2nd, the fleet docked in Singapore. Prince of Wales then became the flagship of Force Z, under the command of Admiral Sir Tom Phillips. Japanese troop-convoys were first sighted on 6 December. Two days later, Japanese aircraft raided Singapore; although the Prince of Wales's anti-aircraft batteries opened fire, they scored no hits and had no effect on the Japanese aircraft. A signal was received from the Admiralty in London ordering the British squadron to commence hostilities, and that evening, confident that a protective air umbrella would be provided by the RAF presence in the region, Admiral Phillips set sail. The object of the sortie was to attack Japanese transports at Kota Bharu, but in the afternoon of 9 December the Japanese submarine I-65 spotted the British ships, and in the evening they were detected by Japanese aerial reconnaissance. By this time it had been made clear that no RAF fighter support would be forthcoming. At midnight a signal was received that Japanese forces were landing at Kuantan in Malaya. Force Z was diverted to investigate. At 02:11 on December 10th, the force was again sighted by a Japanese submarine and at 08:00 arrived off Kuantan, only to discover that the reported landings were a diversion.

At 11:00 that morning the first Japanese air attack began. Eight Type 96 "Nell" bombers dropped their bombs close to Repulse, one passing through the hangar roof and exploding on the 1-inch plating of the main deck below. Despite reports to the contrary, Prince of Wales was struck by only one torpedo. Meanwhile, Repulse avoided the seven torpedoes aimed at her, as well as bombs dropped by six other "Nells" a few minutes later. The torpedo struck Prince of Wales on the port side aft, abaft "Y" Turret, wrecking the outer propeller shaft on that side and destroying bulkheads to one degree or another along the shaft all the way to B Engine Room. This caused rapid uncontrollable flooding and put the entire electrical system in the after part of the ship out of action. Lacking effective damage control, she soon took on a heavy list. A fourth attack was conducted, this one scored hits on Repulse and she sank at 12:33. Six aircraft from this wave also attacked Prince of Wales, hitting her with three torpedoes, causing further damage and flooding. Finally, a 500-kilogram (1,100 lb) bomb hit Prince of Wales's catapult deck, penetrated to the main deck, where it exploded, causing many casualties in the makeshift aid centre in the Cinema Flat. Several other bombs from this attack scored very 'near misses', indenting the hull, popping rivets and causing hull plates to 'split' along the seams and intensifying the flooding. At 13:15 the order to abandon ship was given, and at 13:20 Prince of Wales capsized and sank; Admiral Phillips and Captain Leach were among the 327 fatalities.

Prince of Wales and Repulse were the first capital ships to be sunk solely by naval air power on the open sea (albeit by land-based rather than carrier-based aircraft), a harbinger of the diminishing role this class of ships was to play in naval warfare thereafter. It is often pointed out, however, that contributing factors to the sinking of Prince of Wales were her surface-scanning radars being inoperable in the humid tropic climate, depriving Force Z of one of its most potent early-warning devices and the critical early damage she sustained from the first torpedo. The wreck lies upside down in 223 feet (68 m) of water at 3°33′36″N 104°28′42″E. A Royal Navy White Ensign attached to a line on a buoy tied to a propeller shaft is periodically renewed. The wreck site was designated a 'Protected Place' in 2001 under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, just prior to the 60th anniversary of her sinking.

#second world war#world war 2#royal navy#british#british history#wwii#ww2#naval history#prince of wales#british navy

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOOD QUANTUM Takes a Nasty Bite Out of Colonialism & Whiteness

BLOOD QUANTUM Takes a Nasty Bite Out of Colonialism & Whiteness

Blood Quantum. 2020.

Directed & Written by Jeff Barnaby.

Starring Michael Greyeyes, Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers, Forrest Goodluck, Kiowa Gordon, Olivia Scriven, Stonehorse Lone Goeman, Brandon Oakes, William Belleau, Devery Jacobs, Gary Farmer, Felicia Shulman, Marc Assiniwi, & Natalie Liconti.

Prospector Films

Rated R / 96 minutes

Hor…

View On WordPress

#Alanis Obomsawin#Blood Quantum#Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers#Forrest Goodluck#Incident at Restigouche#Kiowa Gordon#Listuguj#Mi&039;gmaw#Michael Greyes#Settler Colonialism#Whiteness#Zombie

0 notes

Photo

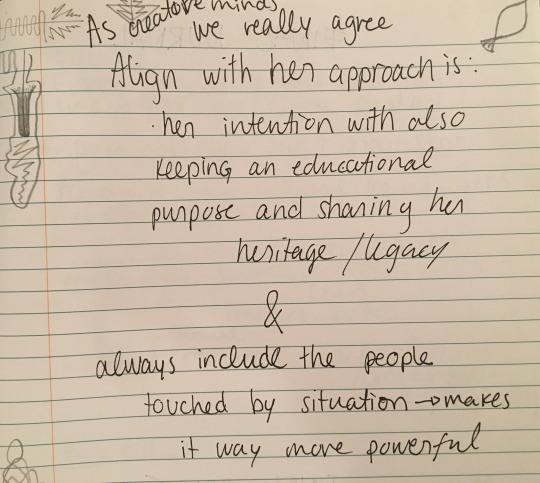

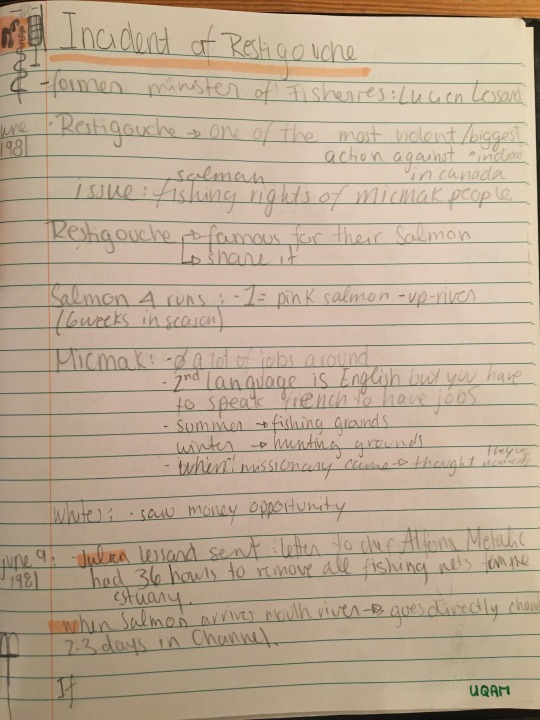

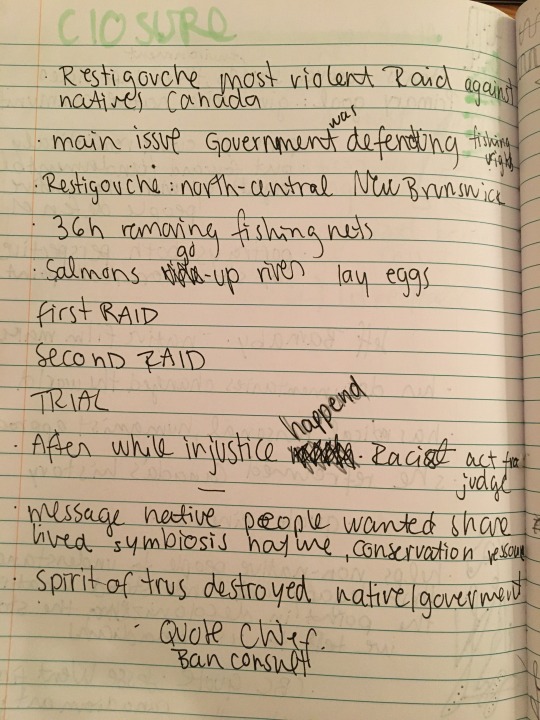

Incident at Restigouche:

-Here are some of my notes on the documentary

- Sita and I discovered the amazing documentarist Alanis Obomsawin

-I am so grateful to have done this research and pushing myself to understand better my country and its history

-The films Alanis have done are important to our culture. Her point of view on giving the voice to those who don’t always have the chance to and her powerful will to educate by sharing her legacy and heritage of this country are two pillars I want to bring in my design practice.

0 notes

Text

Alanis Obomsawin, Incident at Restigouche (1984)

0 notes

Text

Oromocto RCMP calling for potential witnesses in storage facility break-and-enter

Members of the Oromocto RCMP are seeking the public’s help while they investigate a break-in at a storage facility last week.

The incident happened at a facility on Restigouche Road sometime during the evenings of last Friday and Sunday.

Police say one or more people forcefully entered the building and damaged both the building and the property inside.

While details about potential suspects are limited, police say they believe the suspects could have been riding bikes.

No items were stolen during the incident, according to police.

The investigation is ongoing.

Anyone who may have witnessed the event, or may have information is asked to contact the Oromocto RCMP detachment at 506-357-4300 or Crime Stoppers at 1-800-222-8477.

from CTV News - Atlantic https://ift.tt/mRdjivz

0 notes

Text

Belledune — Police warns businesses of fraudulent cheques circulating in northern New Brunswick

Belledune — Police warns businesses of fraudulent cheques circulating in northern New Brunswick

The Northeast District RCMP would like to advise business owners in the Chaleur and Restigouche regions of recent incidents of fraudulent government cheques being used.

The Bathurst RCMP, along with the Beresford, Nigadoo, Petit-Rocher and Pointe-Verte (BNPP) Regional Police, are investigating at least three instances where someone has either cashed or attempted to cash a fraudulent government…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Now Online! Discover Our Indigenous Cinema Collection

On March 22, the NFB launches a new Web page, bringing together 130 titles in English and 90 titles in French from our unparalleled collection of films by Indigenous directors.

VIEW THE INDIGENOUS CINEMA PAGE

Since 1968, the NFB has produced close to 300 films by First Nation, Inuit and Métis directors from right across Canada, offering original and timely perspectives on our country, our history and possible futures from a range of Indigenous perspectives.

Titles include Willie Dunn’s The Ballad of Crowfoot (1968), the first film made at the NFB by an Indigenous director. Sometimes referred to as Canada’s first music video, this short is a powerful look at colonial betrayals told though a ballad composed by Dunn himself about the legendary 19th-century Siksika (Blackfoot) chief. Dunn was a well-known musician on Canada’s folk music scene and a member of the Indian Film Crew—an all-Indigenous film production unit formed at the NFB in 1967. You’ll find other groundbreaking IFC titles like Mike Kanentakeron Mitchell’s You Are on Indian Land (1969), a short documentary that resonated strongly with 1960s civil-rights activists and travelled widely across Canada and the United States, including a famous screening at Alcatraz during the occupation of the infamous prison by members of the American Indian Movement; and Willie Dunn and Martin Defalco’s smouldering documentary The Other Side of the Ledger: An Indian View of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1970)—you’ll never think about the famous retailer in the same way again.

oehttps://http://ift.tt/2GciFWy

You will also find several titles from legendary Abenaki director Alanis Obomsawin’s considerable opus, including Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), her very first film, created with children attending a residential school in the northern Ontario town of Moose Factory; and landmark films such as Incident at Restigouche (1984), which documented two police raids on the Mi’kmaq community of Restigouche in the early 1980s, and Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), Obomsawin’s feature documentary about the 1990 Oka standoff, which was shot over 78 days behind Kanien’kéhaka lines and provides a privileged insider perspective on the historic conflict. The film reverberated around the globe and made history at the Toronto International Film Festival, where it became the first documentary ever to win the Best Canadian Feature Award.

oehttps://http://ift.tt/2HSQlFV

The selection also includes other essential titles by leading Indigenous directors, like Foster Child (1987) and Totem: The Return of the G’psgolox Pole (2003), both by the late Métis director Gil Cardinal; Hands of History (1994) by Loretta Todd; Two Worlds Colliding (2004) by Tasha Hubbard; If the Weather Permits (2003) by Elisapie Isaac; and Finding Dawn (2006) by Christine Welsh.

oehttps://http://ift.tt/2GhIFQj

You can also explore recent titles like Nowhere Land (2015), by Inuk director Bonnie Ammaaq, winner of the Best Short Documentary award at imagineNATIVE in 2016; this river (2016), by celebrated Métis author Katherena Vermette and Erika MacPherson, which won Best Short Doc at imagineNATIVE the following year; Thérèse Ottawa’s award-winning short Red Path (2015); Mobilize, by multi-talented visual artist Caroline Monnet; and We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), by Alanis Obomsawin.

oehttps://http://ift.tt/2HSR6yL

In creating this online destination, our goal was to make it easier for audiences to find films that present Indigenous perspectives on Canadian realities. The site includes biographies for each of the directors and allows users to search for films by the nation/people of the director or the nation/people depicted in the film. Our educational team has also created curated playlists for different age levels.

The collection has been catalogued using a classification system first developed by Kanien’kéhaka (Mohawk) librarian Brian Deer in the 1970s. It’s been adapted by Camille Callison (a member of the Tahltan First Nation) for this collection and reflects best practices in organizing Indigenous collections of knowledge to meet the needs of Indigenous information seekers. For any library geeks who are reading this post, this work is absolutely fascinating—find out more about it.

In 2017, the NFB launched a three-year plan to transform relationships with Indigenous creators and audiences within the context of its role as a public producer and distributor. As a public institution with a mandate to reflect the lives, experiences and perspectives of all Canadians though the works we produce, the NFB has a role to play in the national project of reconciliation.

In its final report, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission underlined the critical role of culture in expanding our understanding of ourselves and our history, exposing truths and laying the groundwork for renewed relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians: “Creative expression can play a vital role in this national reconciliation, providing alternative voices, vehicles and venues for expressing historical truths and present hopes.” Our hope is that this site can play a small part in that process.

The homepage design is based on an original painting by Eruoma Awashish, a graphic artist from the Atikamekw community of Opitciwan. The painting depicts Kakakew, the raven—a recurring character in Awashish’s work. Kakakew is the messenger. “If we take the time to listen to him,” Awashish writes, “he is here to tell us things.” The flowers in the design are Atikamekw motifs that typically adorn bark baskets, canoes, embroidered moccasins, mittens and different clothes. “I integrate them in my painting to honour my culture,” says Awashish.

Many of the films in this collection are currently being screened in communities right across Canada as part of the Aabiziingwashi (Wide Awake) Indigenous cinema screening series. Since its launch in April 2017, there have been over 700 community screenings in every Canadian province and territory.

In coming weeks, new titles will be added to this site, and eventually our full collection of Indigenous-directed works will be available for free. We hope you enjoy exploring the films featured here and that you will come back often!

VIEW THE INDIGENOUS CINEMA PAGE

The post Now Online! Discover Our Indigenous Cinema Collection appeared first on NFB/blog.

Now Online! Discover Our Indigenous Cinema Collection posted first on http://film-streamingsweb.blogspot.com

0 notes

Text

Lawsuit certified: N.B. psychiatric hospital patients get go-ahead to sue province, health authority

A proposed class action lawsuit against the province of New Brunswick and the Vitalite Health Network over alleged ‘abuse, mistreatment and neglect’ at the Restigouche Hospital Centre in Campbellton has gotten the green light to proceed to the courts.

In a decision that was released on Friday, New Brunswick Chief Justice Tracey Deware officially certified the class action lawsuit, giving it the go-ahead.

“It’s quite emotional because it’s been a long time coming,” says Darrell Tidd, one of the plaintiffs in the case.

“The Chief Justice did a good job as far as I’m concerned in reviewing the information that was provided. It’s a detailed report, I think she hit on all the points that were raised.”

The plaintiffs - Tidd and Reid Smith - are both fathers of sons who have spent years at the psychiatric facility, and the action has been brought forward on behalf of patients from 1954 to the present day.

“Darrell and I both agreed that not only are we speaking on behalf of our sons,” says Reid, “but we’re speaking for anybody else that was a patient at the hospital that can’t be heard or is afraid to be outspoken, we will speak on their behalf.”

The legal action was launched after a damning report from New Brunswick’s ombud back in 2019, which described what he called “disturbing” examples of patient mistreatment there.

Charles Murray said that the centre was chronically understaffed and failing to provide adequate care.

“What we observed was that the incident reporting inside the institution isn’t accurate and is compromised in serious ways such that, I’m not sure Vitalite itself is getting an accurate picture of what’s happening there,” Murray said at the time.

Two days after that report was released, a patient at the Restigouche Hospital Centre died unexpectedly. Foul play was ruled out in the death of the 38-year-old man.

In 2019, the law firm representing the plaintiffs said that they’re seeking $500-million in total damages on behalf of the residents.

The next steps for the case include a case management call scheduled for the afternoon of Nov. 3, which will schedule a further hearing on the issues of cost and the litigation plan by the plaintiffs.

from CTV News - Atlantic https://ift.tt/3l0fyEK

0 notes