#caspian sea

Text

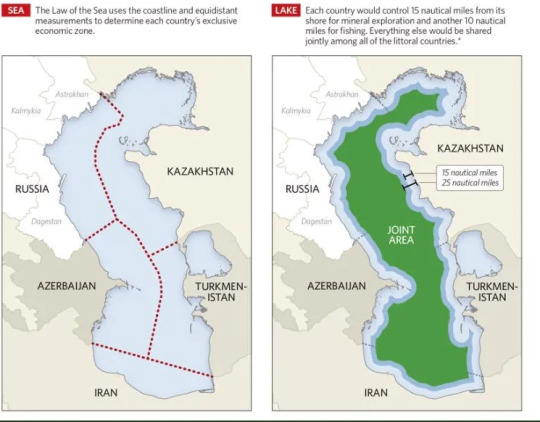

Caspian dilemma: Who controls the Caspian sea?

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

The largest lakes in the world.

#great lakes#caspian sea#Lake Victoria#lake erie#lakes#lady of the lake#geography#lake superior#lake michigan#lake baikal#Comparison

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan

#azerbaijani#travelphotography#landscape#nature#travel#seascape#seaview#sea#samsung#galaxy#beachphotography#beach#sumgait#caspian sea

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soviet ground-effect vehicle, Caspian Sea, Dagestan, Russia

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caspian Sea (1935) - Annemarie Schwarzenbach

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baku, Azerbaijan, in the early 1920s.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

long-exposure lotus flowers by daniel kordan

#nature photography#lotus flower#long exposure#caspian sea#russia#nature#flowers#dreamy#volga river#aes

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Hector Barbossa - by AntVar

#potc fanart#potc#pirates of the caribbean#captain jack sparrow#hector barbossa#pirate lords#pirate lord#on stranger tides#caspian sea#pirate lord of the caspian sea#the brethren cove#pirates of the carribean at worlds end

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the Navy

Mongolia is the second-largest (by area) landlocked country in the word, after Kazakhstan. And that's really not fair to Mongolia, as Kazakhstan borders the Caspian Sea, which is also bordered by four other nations. Mongoli, unlike Kazakhstan, has little reason for a navy, as there's virtually no possibility of the nation engaging in seafaring warfare. (Uvs Lake is one tiny, tiny, tiny exception -- the 1,300 square mile/3,350 km^2 lake has a tiny point in Russia, but that'd be an unlikely place for a battle to break out.)

But Mongolia has a navy. A very small, mostly silly one.

Pictured above is the Sukhbaatar III, a tugboat. It is the flagship of the Mongolian Navy -- a title it has earned in no small part because it is the full complement of the nation's armada. And you'll note that, despite Mongolia having no meaningful aquatic route to a neighboring country, the Sukhbaatar III is sitting in the water. It's stationed in Lake Khovsgol, the nation's largest body of water by volume, itself in the northern part the nation and not too far from Russia -- but still comfortably and entirely within Mongolia's borders.

The tug is operated by a seven-person crew which constitutes the entire navy. That's right, the Mongolian Navy has seven sailors and a tugboat. That's it. And amazingly, it gets even stranger. According to Neatorama, only one of the seven know how to swim.

Historically, the navy served an actual purpose, small as it were. When Mongolia was under Soviet rule, the naval force transported oil from the north of the lake to points south and west, as conditions warranted. (The lake freezes for a few months every year.) A trip across the lake by boat takes about eight hours, and going around the lake (by horse -- there are no roads) takes four days, so in some sense, having a lake-bound navy made sense.

But that's less and less true now. These seven sailors aren't much of a military force, but they're increasingly less of an economic one as well. Not only do they not have any way to steam into battle -- unless someone invades that lake, that is -- but budget cutbacks have required the crew to obtain part-time work shuffling goods and tourists around the lake's coasts, and making ends meet is a challenge.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

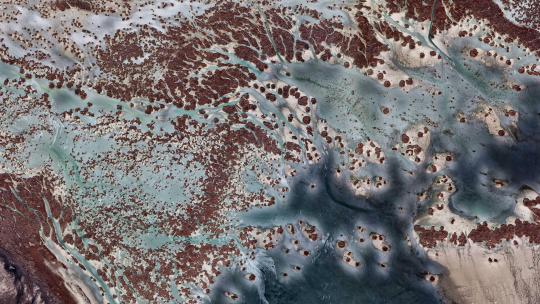

Caspian Sea - Kazakhstan

🌏

4K link

#4k#wallpaper#google earth#satellite view#aerial photography#caspian sea#waterscape#abstract#texture#pattern#earth from space#earth from above#earth art#earth as art#atlas#dji

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just learned about the Caspian Seal and I was perplexed. Like the Baikal Seal, it is landlocked, and makes you wonder "how did they get there?"

Well, I did some light research and here's what I discovered! The earliest distinct pinniped fossil dates back to the Oligocene epoch, about 33-23 million years ago. At this stage in Earth's natural history, what we now call the Mediterranean Sea was far more expansive.

In the image, you can see the outline of the Caspian Sea. It stands to reason that early pinnipeds occupying this area became closed in over time. Not too complicated, but still interesting!

I wonder how these seals are faring, considering the poor state of the Caspian Sea these days.

I heard somewhere that pinnipeds were more closely related to ursinids than canids, but did you know that their closest relatives are actually mustelids? fascinating.

#eukarya#animalia#chordates#mammalia#carnivora#pinnipedia#phocidae#pusa caspica#caspian seal#caspian sea

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If sea levels rose by 60 meters.

118 notes

·

View notes

Link

not sure about the reason yet.

(source: bbc news | 4 dec 2022)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baki, Azerbaijan

#travelphotography#travel#landscape#street#samsung#galaxy#cityscape#seashore#sea shore#caspian sea#city walk

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

One time I accidentally came up with the name “Caspian” without knowing about the Sea... I’m not fucking kidding, why am I like this?

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ingush Grammar

[Ingush Grammar. Johanna Nichols. First Edition: March 2011. University of California Press. Series: UC Publications in Linguistics. Pages: 830. Trim Size: 7 x 10 inches. Illustrations: 1 map. Paperback. ISBN: 9780520098770]

Readers of my book reviews cannot help but notice my interest in – nay, my fascination with – linguistics and languages. I am no stranger to Professor Nichols’s work: I read her award-winning treatise Linguistic Diversity in Time and Space a few years ago and was captivated by her command of language reconstruction principles. Recently, it came to my attention that there might (in principle) be a call for persons to assist in national security-related activities who are fluent in, or at least familiar with, the Northeast Caucasian languages, especially Chechen and Dagestani. The language discussed here, Ingush, is a closely-related language with a relatively high degree of mutual intelligibility with Chechen, Dagestani and Baltsi. Since I couldn’t find a suitable book from which to learn Chechen, I thought I’d check this tidy little volume out.

“Tidy” is not the correct word for this work. It tips the scales at almost 800 pages. However, it is an undeniable tour-de-force of scholarship in the documenting of a comparatively obscure language. Prof. Nichols herself acknowledges that this tome is the culmination of about 30 years of work with Ingush, at least ten of which were spent in the homeland of the language itself, a region now known as Ingushetia in southern Russia adjacent to the Republic of Georgia and Chechnya.

The Northeast Caucasian languages are a small primary language family spoken almost exclusively in the region between the Republic of Georgia and the north end of the Caspian Sea. Significant cities in this region are Ongusht (whence the name Ingush), Groznyy (the capital of Chechnya) and Makhachkala (the capital of Dagestan). Though these languages share many features with Georgian (known as Kartuli to its speakers) and the similarly-named Northwest Caucasian languages (examples are Abkhazi and Cherkessian), they are not, in fact, related to them in any meaningful way. This may seem surprising when one looks at a map of the region. The area covered by these three language groups (Georgian is part of its own tiny language family called the Kartulian languages) is fairly small. However, the area is peppered with mountain ranges that have carved it up geographically to a point where very ancient steppe peoples had settled in individual valleys and had no direct contact with even neighboring valleys for centuries. Little wonder, then, that language families developed independently from a still-more-ancient proto-language (as yet unidentified or classified).

Ingush, as alluded to in the previous paragraph, was named after a prominent community in its sprachbund, or speaking area. Ingush people do not use this term, referring to their language as vai mott (our language) or, if speaking to non-Ingush speakers, vai neaxa mott (our people’s language). Given that the homeland for this language has at least three well-defined geographic zones (alpine highlands, piedmont, and plains), it is not surprising that various dialects of Ingush have emerged. All of these dialects are highly mutually intelligible, far from any objective criteria that would categorize them as distinct languages in their own right.

Nichols herself, in the introductory material, lists Ingush as one of the most morphologically complex languages in her experience, outstripping even daunting native American languages like Lakhota (a Siouan language of the northern Great Plains) and Halkomelem (a Salishan language from the Pacific Northwest in the USA). Ingush has unusually large inventories of elements (phonemes, etc.), a high degree of inflectional synthesis in the verb (this is similar to some native American languages, especially the Athapaskan group) and a variety of categories of words, many of which do not have an analogue in English or any Indo-European language. She comments that this might go some way toward explaining why this book took 30 years to produce!

Since the volume is so detailed, I will simply summarize my observations of its style and completeness. I confess that I haven’t actually read the entire volume – I’ve probably read about 150 pages, or nearly 20% of it all told – but I have dipped into it in various places along its length to see what it was all about. It is impossible for me to imagine that Prof Nichols missed anything; every conceivable component of Ingush seems to be covered here. The book has 35 major sections, any one of which is worthy of at least a semester-long course of study (for the subject itself, not necessarily for Ingush per se). Her writing tone and style strike an admirable balance between being very scholarly (it certainly is that) and yet being profoundly informative to a non-specialist like myself who is also not a trained linguist.

The best affirmation I can make of this book is that it is quite possibly the best template for any field linguist to follow when documenting and characterizing a language. This is certainly true for someone working with an Endangered language, of which there are literally thousands still being spoken (some just barely) in the world today. The level of commitment Prof Nichols has brought to bear on this work seems nothing short of miraculous.

This is definitely not a book for just anyone. Like attempting to read all of Proust in the original French while not actually speaking French, a true appreciation of this book requires enormous patience and strong memory skills. Prof Nichols refers to sections back and forth across the book, of necessity since linguistic elements do not exist in a vacuum. That said, to truly appreciate the scope and even grandeur of this volume will command great mental agility and focus. For anyone who is up to the challenge, I say, “Good luck – and enjoy!” Even if you never speak Ingush or travel to that part of the world, this book will teach you something useful, edifying, and mind-expanding.

[Photo credits with thanks to : Book cover © 2011 University of California Press / Portrait © 2012 Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin]

Kevin Gillette

Words Across Time

28 September 2022

wordsacrosstime

#Kevin Gillette#Ingush Grammar#Words Across Time#wordsacrosstime#September 2022#University of California Press#Johanna Nichols#Linguistics.#Language Reconstruction#Northeast Caucasian Languages#Chechen#Dagestani#Ingush#Baltsi#Ingushetia#Southern Russia#Republic of Georgia#Chechnya#Caspian Sea#Ongusht#Groznyy#Makhachkala#Dagestan#Kartuli#Northwest Caucasian Languages#Kartulian#vai mott#Lakhota#Siouan#Halkomelem

14 notes

·

View notes