#erin dziedzic

Photo

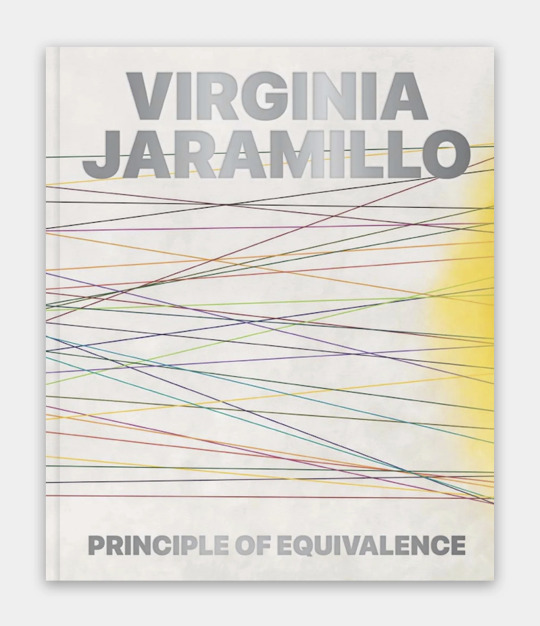

Virginia Jaramillo: Principle of Equivalence, Edited by Erin Dziedzic, Contributions by Matthew Jeffrey Abrams, Barbara Calderon, Iris Colburn, Elizabeth Kirsch and Courtney J. Martin, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO, 2023 [Exhibition: June 1 – August 26, 2023]

#graphic design#art#geometry#mixed media#exhibition#catalogue#catalog#cover#virginia jaramillo#erin dziedzic#matthew jeffrey abrams#barbara calderon#iris colburn#elizabeth kirsch#courtney j. martin#kemper museum of contemporary art#2020s

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

September 2018 First Friday Radar

Do You Have The Time

Friday 6:00-9;00

Curiouser & curiouser

4050 Pennsylvania Ave suite 101

Kansas City, MO 64111

exhibition curated by Camile Elizabeth Messerley featuring the work of b becvar

Reality

Friday 6:00-9;00

Leedy-Voulkos Art Center

2012 Baltimore Ave

Kansas City, MO 64108

Exhibition juried by Erin Dziedzic and Marcus Cain organized by P&M Artworks, this show features artists who…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hyperallergic: Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist

Betty Blayton-Taylor (photo © Adjua Mantebea)

On Sunday, October 2, 2016, in the Bronx, Betty Blayton-Taylor, an unsung figure in the art world, quietly transitioned into the spiritual cosmos she often conjured in her abstract metaphysical work. She was 79. I first met Betty sometime in late 2012 or early 2013. As curator of AARP New York’s first-ever art exhibition, Lasting Legacy: The Journey of YOU, I was tasked with finding artists who exemplified the campaign’s themes of discovering one’s unique talents, exploring new possibilities, and creating lasting legacies. After coming across Betty’s work and meeting her at her home, I knew I wanted her in the exhibition. She embraced me with such warmth — a local legend entrusting her work to the vision of a young, novice curator.

As part of my curatorial research, I wanted to get some insight into Betty’s background. Who was this energetic woman with a home full of art? It turned that out she was, and remains, a big deal. A native of Williamsburg, Virginia, Betty relocated to New York and graduated from Syracuse University in 1959 with a degree in fine arts. After a teaching stint on the island of St. Thomas, she moved to New York City and continued to hone her skills as an artist. It was at this time that she began to merge her interests in art and activism.

Betty became a founding member of the Studio Museum in Harlem and served on its board from 1965 to 1977. Her mission in co-founding the organization was to advance the careers of artists of African descent and to utilize institutional resources and the arts to serve the broader Harlem community.

In collaboration with Victor D’Amico, (director, department of education at the Museum of Modern Art) and Harlem School of the Arts, Betty established the Children’s Art Carnival, an arts education program designed to engage disadvantaged Harlem youth in the arts. (The program was an outgrowth of annual arts workshops held at MoMA from 1942 to 1969 under the same name.) A young Jean-Michel Basquiat was one of the Carnival’s students, and both legendary playwright and director George C. Wolfe and Afro-Caribbean dance icon Marie Brooks taught workshops there. Betty served as executive director from 1969 to 1998, and she remained heavily involved for many years thereafter. In addition, she was a co-founder and board member of Harlem Textile Works, an offshoot of the Children’s Art Carnival in 1984, which offered fabric design workshops, arts education, and job opportunities. Additionally, she served on the board of the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop.

Betty Blayton-Taylor (photo © Adjua Mantebea)

As an artist, Betty had a productive career as a painter, printmaker, illustrator, and sculptor; her work can be seen in the public and private collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, Fisk University, Spelman College, David Rockefeller, Reginald Lewis, Sidney Poitier, and more.

Despite such an illustrious career, her death went largely unnoticed by the mainstream art world, the press, and even some of the institutions and artists she helped build and elevate. Yet her impact reached across space, time, and spheres of influence. She was a groundbreaking force in helping to establish organizations that have advanced artists and communities. And she laid the foundation for much of this in the 1960s and 1970s, in an America polarized by race and gender politics.

Betty deserves to be remembered, honored, and celebrated. On November 19, a memorial service was held at SGI-USA, Culture Center and the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art & Storytelling in New York City. Her work will be included in the exhibition Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today, curated by Erin Dziedzic and Melissa Messina, which will open at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri, in June 2017. The Children’s Art Carnival is planning two exhibitions inspired by her work, and hopefully more commemorations are to come.

In the meantime, we called upon Lowery Stokes Sims, Marline A. Martin, Omo Misha, robin holder, and Thelma Golden to reminisce about Betty Blayton-Taylor: the artist, activist, friend, mentor, and all-around arts warrior.

Betty Blayton-Taylor, “Oversoul Protective Spirit” (2007), acrylic on canvas (courtesy of Betty Blayton-Taylor)

By Lowery Stokes Sims, independent curator and art historian:

I must have first met Betty in the early 1970s, soon after I started working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I became a fan and even served on the board of the Children’s Art Carnival from 1979 to 1982. I was committed to the organization’s dedication to bringing art to children, and in many ways my service on the board was an extension of my first job at the Metropolitan Museum in the Community Programs department. This was the vehicle through which the museum shared resources with the greater NYC arts communities and actualized verbiage about diversity and inclusion. Betty then went on to be a principle in the founding of the Harlem Textile Workshop, and we had a brief collaboration on a product for the store of the Studio Museum in Harlem that had been initiated shortly before I became director. While the product line was never launched, I still have a prototype of a scarf that is a mainstay in my wardrobe.

It is a truism that Betty was a strong artist for whom, like many of her peers — especially the women — her art took a backseat to her decision to work on behalf of the larger art community. She received a B.A. from Syracuse University, where she studied painting and illustration, the latter major an accommodation of parental concerns about her financial future. I also like the fact that due to a peculiarity of Jim Crow Laws, her native state of Virginia paid for her to attend Syracuse University rather than having her attend an in-state school. According to her profile on Wikipedia, Betty had to contend with professors who all wanted her to work like them, and she decided to find her own way of working. In the end, her work may be said to demonstrate a personal synthesis of abstract expressionism and color-field tendencies, demonstrating how her independence posed a potent resistance and personal triumph over racism and sexism in terms of expectations and assumptions about women of her generation with regard to their careers.

I remember Betty’s contagious sense of humor, her endless smile, and her generous laugh. She was always a joy to be around, even as she was maneuvering you to perform some needed task or provide a needed resource for one of the organizations she founded and loved.

Youth at the Children’s Art Carnival in front of a mural they created (image courtesy of Marline A. Martin)

By Marline A. Martin, Executive Director and Curator, Arts Horizons LeRoy Neiman Art Center; Executive Director, Children’s Art Carnival:

As told to Souleo

I first met Betty in 1997 as they were doing a search for the new executive director for the Children’s Art Carnival. I was one of the candidates and subsequently was appointed to the position. I served there from 1997 to 2010.

My first impression of Betty was that she was a hardworking woman. I remember when I received the appointment, saying, “I have big shoes to fill.” Betty’s scope was really wide. She had done a lot of work for the Carnival, brining it into Harlem where it served 5,000 to 10,000 youth per year. She was a champion of the arts.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was one of the Carnival students for a couple of years. He took some classes and was part of a group of young people who were experimenting with their artistry. One of the things I think he really received from the Carnival that made his art appealing was the joy of creativity that is ingrained within children. Instead of going the fine-art route of painting and drawing technique, he found a more expressive way of letting his childhood vision come through his art. I think an amazing thing about the Children’s Art Carnival was the philosophy that existed in terms of art education. For Betty it wasn’t just about technique. It was more about your spirit and how you add that into your work.

I remember stories she would tell me about some of the artists who came from different parts of the world to the Carnival. People would say anyone looking for work as an artist should go see Betty, because the Carnival became an incubator for emerging people like George C. Wolfe. When George first came to New York, he taught theater at the Carnival. Betty gave him one of his first art teaching jobs. Marie Brooks also taught dance at the Carnival. Whatever your art form was, Betty made it into a workshop. I don’t know if there’s an artist around who has been successful in their career and not touched or impacted by Betty Blayton-Taylor.

She will be truly missed, and she was truly loved.

Youth during an Open Studio Workshop at the Children’s Art Carnival (courtesy of Marline A. Martin)

By Omo Misha, Director, Children’s Art Carnival, Curator, and Artist

As told to Souleo

I started working at the Children’s Art Carnival in 2002 as a visual arts instructor, then I became the program manager, left for a few years, and I have since returned as director to help rebuild and rebrand the organization.

Although I worked for the Carnival, my real relationship with Betty began after I had left the Carnival administratively and begun to do more curatorial work. That’s when we got to know each other and when I got a perspective on Betty as an artist. I didn’t know her art before then. So for me as an artist, she has been a great inspiration.

When I think about Betty building and directing the Carnival while simultaneously forging a career as an artist, I realize that people in one sector might not have been as in tune with what she was doing in the other. For me, as someone who wears different hats, I find that really remarkable. I think that is something people should learn from and strive to emulate as an artist. I meet young artists who feel like if they do something else it will take away from their art. But I think all of these things add to your artistic value. I think Betty was an example of that.

At the core of her work as an artist, she was a very spiritual person. That was reflected in her art and the way she taught at the Carnival. She sought, through her own art, to create avenues for people to be more in touch with themselves spiritually. I think that’s why the artwork that came out of the Carnival was so dynamic. Even to this day, I see very few arts institutions that put out the caliber of work I saw coming out of the Carnival. And that is a result of Betty’s vision and her activism.

After I stepped away from the Carnival, I received a greater perspective on the organization. I realized how important this work was that she had done. I never got the sense that Betty thought what she was doing was radical and groundbreaking. She just did what came naturally to her. She came to New York as an artist seeking an artistic community, she found an opportunity to teach for the Museum of Modern Art, she discovered something in it that was inspirational, and she continued to build on that by bringing the Carnival to Harlem. I think she was just being Betty. She was strong and outspoken, sometimes to a fault. But it was that boisterous and lively creative spirit that allowed her to open doors.

Betty Blayton-Taylor, “Ancestors Bearing Light” (2007), acrylic on canvas, 30 inches round (courtesy of BettyBlayton.com)

By robin holder, visual artist:

As told to Souleo

I met Betty in 1978 when I was 26. I was working with the Robert Blackburn Printmaking Workshop as the coordinator and then the assistant director for the workshop. Bob never had enough money to pay anybody, so anytime he was short on funds he would send some of us up to the Carnival for Betty to give us part-time gigs. Betty was also a board member for the Workshop and did her prints there when she had the time.

After I went up to the Carnival one day, I began working there on and off as a teaching artist. I recall that she was always in dire straits financially with the organization because she was very idealistic and overextended herself. She would do things first and then see how she would finance it. Betty was always diligently writing grants and reports and projects. One day I went up to her little office on the third floor of the brownstone. She was really happy and said, “I got rid of our deficit.” I said, “That’s fantastic. How did you do it?” She picked up a pencil and said, “I just erased it.” I thought that was hysterical. She had such a good sense of humor.

I connected with Betty right away. We became friends largely because of a real commitment to and interest in the spiritual nature of life and how that can be reflected in artwork. At the same time, she had some serious personal problems, but regardless of that fact, she was able to stay focused. That’s what was so remarkable about Betty. There was always a real dynamic energy she was giving to the Carnival, one that, at times, you sensed she would have liked to direct to her own work as an artist.

A difficult thing that has to do with elitism in the art world is that community art is often regarded as “lesser than” the arts. Betty was the founder and director of a community-based African-American organization, and because of that I hope she is not sidelined in importance, [because she was] a genuinely gifted and hardworking abstract painter. Sometimes I wonder whether, if Betty had spent more of her life developing her work, and if there was more of a receptive art world to female African-American artists, she might have been more high profile.

The experimentation she did with transparent layering of shapes and color and circular canvases was quite important. She had this high skill level of being a painter with a very exploratory approach to the imagery that she developed. When I look at her work, I know it’s her work. She was able to create her own visual language, which is the work of somebody who has something to say and is an original.

Founding members and staff of the Studio Museum in Harlem, including Betty Blayton-Taylor, second from the right (courtesy of the Studio Museum in Harlem)

By Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator, the Studio Museum in Harlem:

Betty Blayton-Taylor was a singular artist, educator, activist, and advocate. The Studio Museum in Harlem is incredibly proud of her important role as a founder and longtime champion of our institution. Without question, her commitment to artists of African descent continues to animate nearly every aspect of our work, and it inspires my work as director every day.

As a founding board member of the Studio Museum in Harlem, Betty championed the museum before it even existed. She had a clear vision of the power and possibility of art and artists to impact a life, a neighborhood, a world. She served on the Studio Museum’s board from 1965 to 1977, during which — in addition to her membership on the executive committee as secretary — she advocated for both the ideals of the museum and the very real challenges of sustaining a fledgling nonprofit, work she knew well from co-founding and leading the Children’s Art Carnival.

When Betty articulated her initial vision — to create the kind of museum that could meaningfully serve her Harlem students in their own neighborhood — there was no precedent for an institution of this kind. As an educator, she was deeply committed to creating access for young people frequently discouraged from entering museums and visual arts institutions in New York City. And as an artist, she created works that have engaged and inspired audiences around the world, including here at the Studio Museum.

Betty not only opened doors, she built new doors — doors that, nearly 50 years later, remain permanently open in her students’ own backyard. She is sincerely missed, but her legacy will continue to guide our planning and preparation for the Studio Museum’s next half-century, and beyond.

The post Remembrances of Betty Blayton-Taylor, Studio Museum Co-Founder and Harlem Arts Activist appeared first on Hyperallergic.

from Hyperallergic http://ift.tt/2iVQtfM

via IFTTT

0 notes