#not even starting on the rank disparity between a lieutenant and a cadet

Text

seeing smutty pre-kerberos fanart in a main voltron tag is just a gross reminder that Shieth is pedophilic by nature and fans of it are either bending over backwards trying to get around that to varying degrees of success, don’t have the basic critical thinking skills to recognize it, or genuinely don’t care.

#I can handle the concept of some romantic attraction way late into the series#post time-whale#but PRE-KERBEROS#it's an insult to Shiro#Keith was a teenager- a CHILD. Shiro was in his mid-twenties#not even starting on the rank disparity between a lieutenant and a cadet

1 note

·

View note

Text

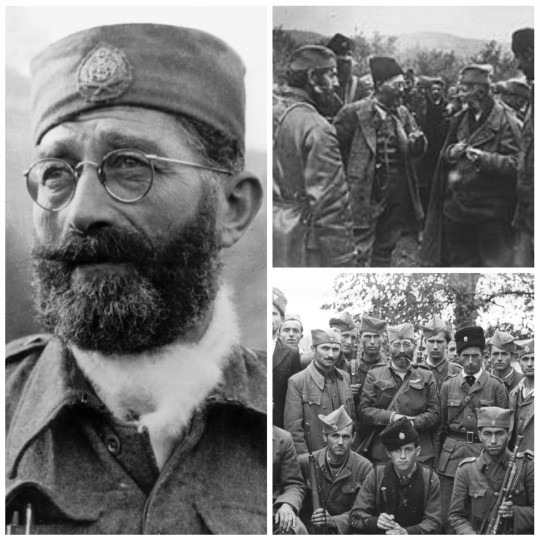

• Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović was a Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. A staunch royalist, he retreated to the mountains near Belgrade when the Germans overran Yugoslavia in April 1941 and there he organized bands of guerrillas known as the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army.

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović was born on April 27th, 1893 in Ivanjica, Kingdom of Serbia to Mihailo and Smiljana Mihailović. His father was a court clerk. Orphaned at seven years of age, Mihailović was raised by his paternal uncle in Belgrade. As both of his uncles were military officers, Mihailović himself joined the Serbian Military Academy in October 1910. He fought as a cadet in the Serbian Army during the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 and was awarded the Silver Medal of Valor at the end of the First Balkan War, in May 1913. At the end of the Second Balkan War, during which he mainly led operations along the Albanian border, he was given the rank of second lieutenant as the top soldier in his class, ranked sixth at the Serbian military academy. He served in World War I and was involved in the Serbian Army's retreat through Albania in 1915. He later received several decorations for his achievements on the Salonika Front. Following the war, he became a member of the Royal Guard of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes but had to leave his position in 1920 after taking part in a public argument between communist and nationalist sympathizers.

He was subsequently stationed to Skopje. In 1921, he was admitted to the Superior Military Academy of Belgrade. In 1923, having finished his studies, he was promoted as an assistant to the military staff, along with the fifteen other best alumni of his promotion. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in 1930. That same year, he spent three months in Paris, following classes at the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr. Some authors claim that he met and befriended Charles de Gaulle during his stay, although there is no known evidence of this. In 1935, he became a military attaché to the Kingdom of Bulgaria and was stationed to Sofia. On September 6th, 1935, he was promoted to the rank of colonel. Mihailović then came in contact with members of Zveno and considered taking part in a plot which aimed to provoke Boris III's abdication and the creation of an alliance between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, but, being untrained as a spy, he was soon identified by Bulgarian authorities and was asked to leave the country. He was then appointed as an attaché to Czechoslovakia in Prague.

His military career almost came to an abrupt end in 1939, when he submitted a report strongly criticizing the organization of the Royal Yugoslav Army. Among his most important proposals were abandoning the defence of the northern frontier to concentrate forces in the mountainous interior; re-organizing the armed forces into Serb, Croat, and Slovene units in order to better counter subversive activities; and using mobile Chetnik units along the borders. Milan Nedić, the Minister of the Army, was incensed by Mihailović's report and ordered that he be confined to barracks for 30 days. Afterwards, Mihailović became a professor at Belgrade's staff college. In the summer of 1940, he attended a function put on by the British military attaché for the Association of Yugoslav Reserve NCOs. The meeting was seen as highly anti-Nazi in tone, and the German ambassador protested Mihailović's presence. Nedić once more ordered him confined to barracks for 30 days as well as demoted and placed on the retired list. These last punishments were avoided only by Nedić's retirement in November. In the years preceding the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia, Mihailović was stationed in Celje, Drava Banovina (modern Slovenia). At the time of the invasion, Colonel Mihailović was an assistant to the chief-of-staff of the Yugoslav Second Army in northern Bosnia. He briefly served as the Second Army chief-of-staff prior to taking command of a "Rapid Unit" (brzi odred) shortly before the Yugoslav High Command capitulated to the Germans on April 17th, 1941.

Following the invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia by Germany, Italy, Hungary, a small group of officers and soldiers led by Mihailović escaped in the hope of finding Yugoslavian units still fighting in the mountains. After skirmishing with several Ustaše and Muslim bands and attempting to sabotage several objects, Mihailović and about 80 of his men crossed the Drina River into German-occupied Serbia. Mihailović planned to establish an underground intelligence movement and establish contact with the Allies, though it is unclear if he initially envisioned to start an actual armed resistance movement. For the time being, Mihailović established a small nucleus of officers with an armed guard, which he called the "Command of Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army". After arriving at Ravna Gora in early May 1941, he realized that his group of seven officers and twenty-four non-commissioned officers and soldiers was the only one. He began to draw up lists of conscripts and reservists for possible use. His men at Ravna Gora were joined by a group of civilians, mainly intellectuals from the Serbian Cultural Club, who took charge of the movement's propaganda sector. The Chetniks of Kosta Pećanac, which were already in existence before the invasion, did not share Mihailović's desire for resistance. In order to distinguish his Chetniks from other groups calling themselves Chetniks, Mihailović and his followers identified themselves as the "Ravna Gora movement". The stated goal of the Ravna Gora movement was the liberation of the country from the occupying armies of Germany, Italy and the Ustaše.

Mihailović spent most of 1941 consolidating scattered remnants and finding new recruits. In August, he set up a civilian advisory body, the Central National Committee, composed of Serb political leaders including some with strong nationalist views such as Dragiša Vasić and Stevan Moljević. Mihailović first established radio contact with the British in September 1941, when his radio operator raised a ship in the Mediterranean. On September 13th, Mihailović's first radio message to King Peter's government-in-exile announced that he was organizing Yugoslavia remnants to fight against the Axis powers. Mihailović also received help from officers in other areas of Yugoslavia, such as Slovene officer Rudolf Perinhek, who brought reports on the situation in Montenegro. Mihailović sent him back to Montenegro with written authorization to organize units there. Mihailović's strategy was to avoid direct conflict with the Axis forces, intending to rise up after Allied forces arrived in Yugoslavia. Mihailović's Chetniks had had defensive encounters with the Germans, but reprisals and the tales of the massacres in the Axis puppet state of Croatia made them reluctant to engage directly in armed struggle, except against the Ustaše in Serbian border areas. By the end of August, Mihailović's Chetniks and Josep "Tito" Broz's Partisans began attacking Axis forces, sometimes jointly despite their mutual diffidence, and captured numerous prisoners. On October 28th, 1941 Mihailović received an order from the Prime Minister of the Yugoslav Government in exile Dušan Simović who urged Mihailović to avoid premature actions and avoid German reprisals. Mihailović discouraged sabotage due to German reprisals (such as more than 3,000 killed in Kraljevo and Kragujevac) unless some great gain could be accomplished. Instead, he favoured sabotage that could not easily be traced back to the Chetniks. His reluctance to engage in more active resistance meant that most sabotage carried out in the early period of the war were due to efforts by the Partisans, and Mihailović lost several commanders and a number of followers who wished to fight the Germans to the Partisan movement.

Even though Mihailović initially asked for discreet support, propaganda from the British and from the Yugoslav government-in-exile quickly began to exalt his feats. The creation of a resistance movement in occupied Europe was received as a morale booster. Mihailović soon realized that his men did not have the means to protect Serbian civilians against German reprisals. The prospect of reprisals also fed Chetnik concerns regarding a possible takeover of Yugoslavia by the Partisans after the war, and they did not wish to engage in actions that might ultimately result in a post-war Serb minority. Mihailović's strategy was to bring together the various Serb bands and build an organization capable of seizing power after the Axis withdrew or were defeated, rather than engaging in direct confrontation with them. In contrast to the reluctance of Chetnik leaders to directly engage the Axis forces, the Partisans advocated open resistance, which appealed to those Chetniks desiring to fight the occupation. On September 19th, 1941, Tito met with Mihailović to negotiate an alliance between the Partisans and Chetniks, but they failed to reach an agreement as the disparity of the aims of their respective movements was great enough to preclude any real compromise. In mid-November, the Germans launched an offensive against the Partisans, Operation Western Morava, which bypassed Chetnik forces. Having been unable to quickly overcome the Chetniks, faced with reports that the British considered Mihailović as the leader of the resistance, and under pressure from the German offensive, Tito approached Mihailović with an offer to negotiate, which resulted in talks and later an armistice between the two groups on November 21st. Mihailović did not resume radio transmissions with the Allies before January 1942. In early 1942, the Yugoslav government-in-exile reorganized and appointed Slobodan Jovanović as prime minister, and the cabinet declared the strengthening of Mihailović's position as one of its primary goals. On January 11th, Mihailović was named "Minister of the Army, Navy and Air Forces" by the government-in-exile.

In Montenegro, Mihailović found a complex situation. The local Chetnik leaders, Bajo Stanišić and Pavle Đurišić, had reached arrangements with the Italians and were cooperating with them against the communist-led Partisans. Mihailović later claimed at his trial in 1946 that he was unaware of these arrangements prior to his arrival in Montenegro, and had to accept them once he arrived. Mihailović believed that Italian military intelligence was better informed than he was of the activities of his commanders. He tried to make the best of the situation and accepted the appointment of Blažo Đukanović as the figurehead commander of "nationalist forces" in Montenegro. While Mihailović approved the destruction of communist forces, he aimed to exploit the connections of Chetniks commanders with the Italians to get food, arms and ammunition in the expectation of an Allied landing in the Balkans. Having become more and more concerned with domestic enemies and concerned that he be in a position to control Yugoslavia after the Allies defeated the Axis, Mihailović concentrated from Montenegro on directing operations, in the various parts of Yugoslavia, mostly against Partisans, but also against the Ustaše and Dimitrije Ljotić's Serbian Volunteer Corps (SDK). During the autumn of 1942, Mihailović's Chetniks at the request of the British organization sabotaged several railway lines used to supply Axis forces in the Western Desert of northern Africa. Adolf Hitler wrote to Benito Mussolini on February 16th, 1943, demanding that in addition to the partisans be pursued the chetniks who possessed "a special danger in the long-term plans that Mihailovic's supporters were building." Hitler adds: "In any case, the liquidation of the Mihailovic movement will no longer be an easy task, given the forces at its disposal and the large number of armed Chetniks". From the beginning of 1943, General Mihailovic prepared his units for the supports of Allied landing on the Adriatic coast. General Mihailovic hoped that the Western Alliance would open the Second Front in the Balkans.

Mihailović had great difficulties controlling his local commanders, who often did not have radio contacts and relied on couriers to communicate. He was, however, apparently aware that many Chetnik groups were committing crimes against civilians and acts of ethnic cleansing; according to Pavlowitch, Đurišić proudly reported to Mihailović that he had destroyed Muslim villages, in retribution against acts committed by Muslim militias. While Mihailović apparently did not order such acts himself and disapproved of them, he also failed to take any action against them, being dependent on various armed groups whose policy he could neither denounce nor condone. Many terror acts were committed by Chetnik groups against their various enemies, real or perceived, reaching a peak between October 1942 and February 1943. Chetnik ideology encompassed the notion of Greater Serbia, to be achieved by forcing population shifts in order to create ethnically homogeneous areas. Chetniks forces engaged in numerous acts of violence including massacres and destruction of property, and used terror tactics to drive out non-Serb groups. Mihailović was certainly aware of both the ideological goal of cleansing and of the violent acts taken to accomplish that goal. In November 1942, Captain Hudson cabled to Cairo that the situation was problematic, that opportunities for large-scale sabotage were not exploited because of Mihailović's willingness to avoid reprisals and that, while waiting for an Allied landing and victory, the Chetnik leader might come to "any sound understanding with either Italians or Germans which he believed might serve his purposes without compromising him", in order to defeat the communists. A British senior officer, Colonel S. W. Bailey, was then sent to Mihailović and was parachuted into Montenegro on Christmas Day. His mission was to gather information and to see if Mihailović had carried out necessary sabotages against railroads. During the following months, the British concentrated on having Mihailović stop Chetnik collaboration with Axis forces and perform the expected actions against the occupiers, but they were not successful. In January 1943, the SOE reported to Churchill that Mihailović's subordinate commanders had made local arrangements with Italian authorities, although there was no evidence that Mihailović himself had ever dealt with the Germans. Bailey reported that Mihailović was increasingly dissatisfied with the insufficient help he was receiving from the British. Mihailović's movement had been so inflated by British propaganda that the liaison officers found the reality decidedly below expectations.

On February 28th, 1943, in Bailey's presence, Mihailović addressed his troops in Lipovo. Bailey reported that Mihailović had expressed his bitterness over "perfidious Albion" who expected the Serbs to fight to the last drop of blood without giving them any means to do so, had said that the Serbs were completely friendless, that the British were holding King Peter II and his government as virtual prisoners, and that he would keep accepting help from the Italians as long as it would give him the means to annihilate the Partisans. The British officially protested to the Yugoslav government-in-exile and demanded explanations regarding Mihailović's attitude and collaboration with the Italians. Mihailović answered to his government that he had had no meetings with Italian generals. Also in early 1943, the tone of the BBC broadcasts became more and more favourable to the Partisans, describing them as the only resistance movement in Yugoslavia, and occasionally attributing to them resistance acts actually undertaken by the Chetniks. During the Allied invasion of Italy the Italians heavily supported the Chetniks in the hope that they would deal a fatal blow to the Partisans. The Germans disapproved of this collaboration, about which Hitler personally wrote to Mussolini. At the end of February, shortly after his speech, Mihailović himself joined his troops in Herzegovina near the Neretva in order to try to salvage the situation. The Partisans nevertheless defeated the opposing Chetniks troops, who were in a state of disarray, and managed to go across the Neretva. In March, the Partisans negotiated a truce with Axis forces in order to gain some time and use it to defeat the Chetniks. While Ribbentrop and Hitler finally overruled the orders of their subordinates and forbade any such contacts, the Partisans benefited from this brief truce, during which Italian support for the Chetniks was suspended, and which allowed Tito's forces to deal a severe blow to Mihailović's troops. In late May, after regaining control of most of Montenegro, the Italians turned their efforts against the Chetniks, at least against Mihailović's forces, and put a reward of half-a-million lire for the capture of Mihailović, and one million for the capture of Tito.

In April and May 1943, the British sent a mission to the Partisans and strengthened their mission to the Chetniks. Mihailović returned to Serbia and his movement rapidly recovered its dominance in the region. Receiving more weapons from the British, he undertook a series of actions and sabotages, disarmed Serbian State Guard (SDS) detachments and skirmished with Bulgarian troops, though he generally avoided the Germans, considering that his troops were not yet strong enough. In Serbia, his organization controlled the mountains where Axis forces were absent. The United States sent liaison officers to join Bailey's mission with Mihailović, while also sending men to Tito. The Germans, in the meantime, became worried by the growing strength of the Partisans and made local arrangements with Chetnik groups, though not with Mihailović himself. From the beginning of 1943, British impatience with Mihailović grew. From the decrypts of German wireless messages, Churchill and his government concluded that the Chetniks' collaboration with the Italians went beyond what was acceptable and that the Partisans were doing the most severe damage to the Axis. By November and December 1943, the Germans had realized that Tito was their most dangerous opponent. At the end of October, the local signals decrypted in Cairo had disclosed that Mihailović had ordered all Chetnik units to co-operate with Germany against the Partisans. The British were more and more concerned about the fact that the Chetniks were more willing to fight Partisans than Axis troops. At the third Moscow Conference in October 1943, Anthony Eden expressed impatience about Mihailović's lack of action. The report of Fitzroy Maclean, liaison officer to the Partisans, convinced Churchill that Tito's forces were the most reliable resistance group. On December 10th, Churchill met King Peter II in London and told him that he possessed irrefutable proofs of Mihailović's collaboration with the enemy and that Mihailović should be eliminated from the Yugoslav cabinet. Also in early December, Mihailović was asked to undertake an important sabotage mission against railways, which was later interpreted as a "final opportunity" to redeem himself. However, possibly not realizing how Allied policy had evolved, he failed to give the go-ahead. This hastened the British's decision to withdraw their thirty liaison officers to Mihailović. The mission was effectively withdrawn in the spring of 1944.

At the end of August 1944, the Soviet Union's Red Army arrived on the eastern borders of Yugoslavia. In early September, it invaded Bulgaria and coerced it into turning against the Axis. Mihailović's Chetniks, meanwhile, were so badly armed to resist the Partisan incursions into Serbia that some of Mihailović's officers, including Nikola Kalabić, Neško Nedić and Dragoslav Račić, met German officers in August to arrange a meeting of Mihailović with Neubacher and to set forth the conditions for increased collaboration. From the existing accounts, they met in a dark room and Mihailović remained mostly silent, so much so that Nedić was not even sure afterwards that he had actually met the real Mihailović. According to British official Stephen Clissold, Mihailović was initially very reluctant to go to the meeting, but was finally convinced by Kalabić. It appears that Nedić offered to obtain arms from the Germans, and to place his Serbian State Guard under Mihailović's command, possibly as part of an attempt to switch sides as Germany was losing the war. Neubacher favoured the idea, but it was vetoed by Hitler, who saw this as an attempt to establish an "English fifth column" in Serbia. As the Red Army approached, Mihailović thought that the outcome of war would depend on Turkey entering the conflict, followed at last by an Allied incursion in the Balkans. He called upon all Yugoslavs to remain faithful to the King, and claimed that Peter had sent him a message telling him not to believe what he had heard on the radio about his dismissal. His troops started to break up outside Serbia in mid-August, as he tried to reach to Muslim and Croat leaders for a national uprising. Mihailović ordered a general mobilization on September 1st; his troops were engaged against the Germans and the Bulgarians, while also under attack by the Partisans. German sources confirm the loyalty of Mihailović and forces under his direct influence in this period. Mihailović's movement collapsed in Serbia under the attacks of Soviets, Partisans, Bulgarians and fighting with the retreating Germans. Still hoping for a landing by the Western Allies, he headed for Bosnia with his staff, McDowell and a force of a few hundred. He set up a few Muslim units and appointed Croat Major Matija Parac as the head of an as yet non-existent Croatian Chetnik army. Nedić himself had fled to Austria. On May 25th, 1945, he wrote to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, asserting that he had always been a secret ally of Mihailović. Now hoping for support from the United States, Mihailović met a small British mission between the Neretva river and Dubrovnik, but realized that it wasn't the signal of the hoped-for landing. McDowell was evacuated on 1 November and was instructed to offer Mihailović the opportunity to leave with him. Mihailović refused, as he wanted to remain until the expected change of Western Allied policy.

With their main forces in eastern Bosnia, the Chetniks under Mihailović's personal command in the late months of 1944 continued to collaborate with Germans. In January 1945, Mihailović tried to regroup his forces on the Ozren heights, planning Muslim, Croatian and Slovenian units. His troops were, however, decimated and worn out, some selling their weapons and ammunition, or pillaging the local population. In April, Mihailović set out for northern Bosnia, on a 280 km-long march back to Serbia, aiming to start over a resistance movement, this time against the communists. His units were decimated by clashes with the Ustaše and Partisans, as well as dissension and typhus. In May, they were attacked and defeated by Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), the successor to the Partisans, in battle of Zelengora. Mihailović managed to escape with 1,000–2,000 men, who gradually dispersed. Mihailović himself went into hiding in the mountains with a handful of men. The Yugoslav authorities wanted to catch Mihailović alive in order to stage a full-scale trial. He was finally caught on March 13th, 1946. The elaborate circumstances of his capture were kept secret for sixteen years. According to one version, Mihailović was approached by men who were supposedly British agents offering him help and an evacuation by aeroplane. After hesitating, he boarded the aeroplane, only to discover that it was a trap set up by the OZNA. The trial of Draža Mihailović opened on June 10th, 1946. His co-defendants were other prominent figures of the Chetnik movement as well as members of the Yugoslav government-in-exile, such as Slobodan Jovanović, who were tried in absentia, but also members of ZBOR and of the Nedić regime. Mihailović evaded several questions by accusing some of his subordinates of incompetence and disregard of his orders. The trial shows, according to Jozo Tomasevich, that he never had firm and full control over his local commanders. A Committee for the Fair Trial of General Mihailović was set up in the United States, but to no avail. Mihailović is quoted as saying, in his final statement, "I wanted much; I began much; but the gale of the world carried away me and my work."

Mihailović was convicted of high treason and war crimes, and was executed on July 17th, 1946 at the age of 53. He was executed together with nine other officers in Lisičiji Potok, about 200 meters from the former Royal Palace. His body was reportedly covered with lime and the position of his unmarked grave was kept secret. In March 2012, Vojislav Mihailović filed a request for his grandfather's rehabilitation in the high court. The announcement caused a negative reaction in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia alike. Former Croatian President Ivo Josipović stated that the attempted rehabilitation is harmful for Serbia and contrary to historical facts. He elaborated that Mihailović "is a war criminal and Chetnikism is a quisling criminal movement". The High Court rehabilitated Draža Mihailović on May 14th, 2015. This ruling reverses the judgment passed in 1946, sentencing Mihailović to death for collaboration with the occupying Nazi forces and stripping him of all his rights as a citizen. According to the ruling, the Communist regime staged a politically and ideologically motivated trial. The revised image of Mihailović is not shared in non-Serbian post-Yugoslav nations. In Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina analogies are drawn between war crimes committed during World War II and those of the Yugoslav Wars, and Mihailović is "seen as a war criminal responsible for ethnic cleansing and genocidal massacres." Monuments to Draža Mihailović exist on Ravna Gora (1992), Ivanjica, Lapovo, Subjel, Udrulje near Višegrad, Petrovo and within cemeteries in North America.

#second world war#world war ii#world war 2#military history#wwii#history#german history#yugoslav partisans#long post#Yugoslavia history#british history#partisans#biography

16 notes

·

View notes