#yffing

Text

Totems and banners: Hild's Elmet

What banners and totems might Hild's people have carried in the early seventh-century of MENEWOOD? I don't know. But here are some guesses, with pictures!

What kind of colours, banners, totems, or standards did warriors of Hild’s time carry?

In day-to-day life?

When geared up for battle?

I don’t know. I don’t even know for certain how fighting groups in Britain were organised 1400 years ago.

Having said that, most of us—writers, readers, researchers—are so used to seeing film, tv, vases, sculptures, and other cultural representations of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

"“Amen,” Hild said.

They watched the Yr moving, stately and steely, east.

“May Christ forgive him,” Rhin said. “I cannot.”

She would not even try. One day she would tear the heart from his chest.”

Menewood, Nicola Griffith

#i would ride into battle for hild yffing#i need you all to read these books thanks#menewood#hild#nicola griffith#early medieval#of swords and saints#touch me and you'll burn

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

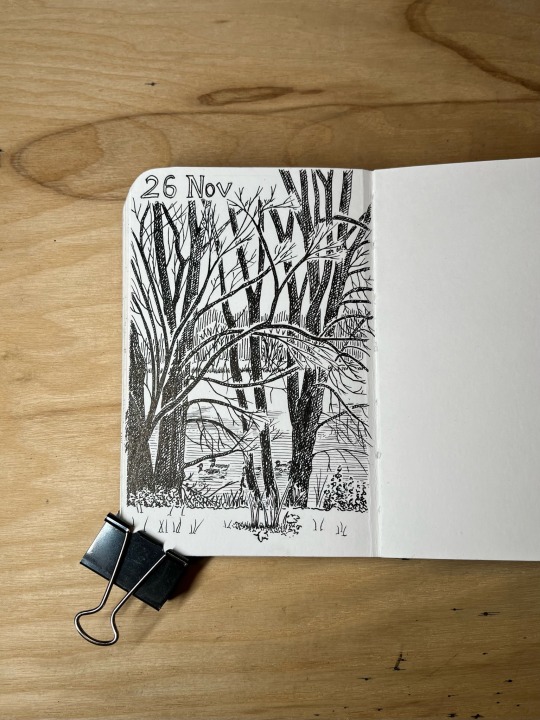

2023 Week 48: A layer of snow. It quickly melted, though the lake is now mostly ice.

Currently reading Menewood by Nicola Griffith. From Chapter 15: “But Hild knew her mother’s thinking. Hild would ride into Menewood like the lady of Elmet of old—as though backed by a full granary and thronging fold, a busy dairy, and fields under the plough—and a healthy child before her. From far enough away the people of Menewood, new and old, easy and uncertain, would see only the glitter and the high-stepping mare, the gleaming Yffing chestnut hair, escorted by glinting spearpoints and led by king’s gesiths. They would not see how gaunt she was beneath her furs, how her dress hung and bagged; they would not guess at the runnelled twisting scar on her hip, the ragged gashes hidden by her fine linen sleeves.”

#pen and ink#ink drawing#line drawing#sketchbook#currently reading#nature drawing#nature illustration#pen and ink drawing#nature sketch#tree drawing

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

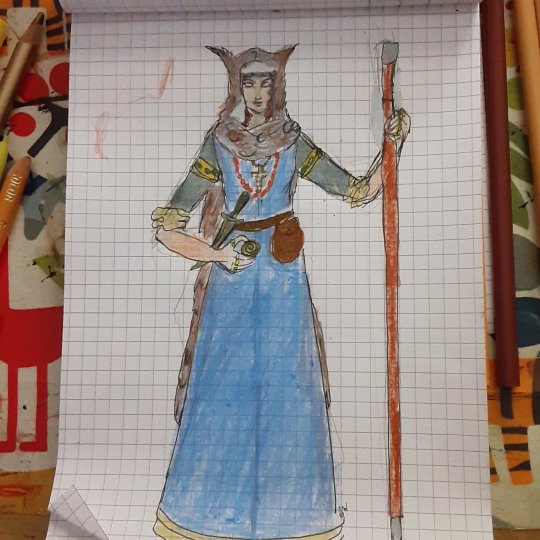

"Her left-hand path was light and life and lifting up; her right, the dark and death and destruction. Staff and seax. Skirt and sword. Book and blade. She was the sow Cadwallon would see; she was the boar he would feel, the Yffing boar who would rip him open and spill him out."

Menewood, Nicola Griffith

1 note

·

View note

Text

I can't stop reading Menewood, a book I keep calling "Medieval War and Peace" but is really about gangs of smelly guys roving around Yorkshire and a lady from Leeds who just wants to eat some damn bread. Here's our protagonist, the uncanny Hild Yffing in her Cath Llew get up.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Menewood", by Nicola Griffith

An unbelievable banger. If she lived in the modern era, Hild Yffing would have been the greatest 4X gamer of all time.

0 notes

Text

bem-vindo, meu amor

setting a pair of rules before starting:

no minors. i may fuck babysitters but that doesnt make me one.

for silly little whores, who are too silly to connect even one braincel.... no hate, racism or anything similar.

senna is my safeword. i will highlight it with green at the beginning of your ask if you said something that made me feel uncomfortable

ordem is your safeword, minha garotinha. use it whenever daddy makes you feel uncomfortable

once you follow me, i will be sending you a dm asking for an id picture with everything crossed but your birth date. can't risk it for someone who doesnt want to obey pai rules

^^^^ no interaction before confirmation ^^^^

no roleplay in dms, this is mostly because *cough* mod is a fatass and forgets ..... them *cough*

no double asks. ask prior your resend if ive received certain ask

when im online

everyday after morning practice ends and rubens finishes school -> 16-23 gmt-3

my yes and no

NO -> infantilization, scat, lolis, furries, yffing.

YES -> everything else

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: ‘Hild’

Hild by Nicola Griffith

My rating: 2 of 5 stars

This is not a novel. This is a doctoral thesis of Middle Ages Britain polity, bearing all the greasepaint and false promise of warrior saints, kingdoms on the cusp of unity, an economy bespoke to the natural order, and an emerging and presumed grasp of regional geopolitics that is rooted more in conscientious and urbane side-taking than in whether distrustful cousins bend a knee and kiss a ring. It's a fine thesis, really. But as a novel, this is a considerable waste of energy.

HILD huddles and adheres close to the microscopic and the minute — the patterns of falcons in springtime, the density of clouds in winter — but looses and cares not for the feverish goings-on of humanity that yield closer to the earth: entertaining the inevitability of war and generally doing anything but talk, talk, talk. This book documents the efforts of a young woman, Hild, and her efforts to keep a clever but impossibly suspicious king in power (and saving her own hide in the process). Readers must be forewarned, history, in most cases, is quite boring.

The nature of historical fiction need not be so duty-bound and constrained by the author's feverish enrapture of the land and its people to inhibit the efforts of an otherwise temperamental story to make itself known. As for HILD, nothing of narrative consequence occurs in the first 80 pages of the book. And even then, when the young protagonist, deemed a seer and prophesier of future events, claims her home is under siege, she is given no agency to guide her omen through to its natural conclusion; instead, she's dumped in a port town for several years (and another 80 pages). She warned the king and ended up saving Bebbanburg. Good for her. So now readers must wander cow paddies, follow the rhythms of streams and learn how to count using slave trader's abacus until Hild has another "vision"? That's rough.

To much surprise, there is very little actual war/conflict in this book. And while scenes come alive when Hild takes up the blade to lead a band of war hounds to settle disputes with bandits or to protect the land from purveyors from the south, two brief but meaningful battle scenes in a Middle Ages tome of 530+ pages is quite paltry.

Much of the book's poor rendering of its own story dynamics — that is, manifesting the believable and engaging connective tissue that wills key events into a single pattern — is due to the title's unfathomably inarticulate and labyrinthine nest of political squabbling. The Saxons. The Angles. The Irish. The Frisians. The Yffings. The Idings. The Picts. Kings and lords and aeldermen and soldiers and slaves and priests and bishops.

The author spends so much time and energy attempting to convince readers of the authenticity of the web that binds together Britain, readers are drowned, chapter after chapter, in the muddy sophistry of characters whom readers shall never meet and of verdant hillocks they shall never traverse. So much time is dedicated to tossing around names and places and alliances with little or no context, it's easy if not preferable to glide beneath the thunder of details and wait for the rain to pass.

To this end, little actually happens in HILD. There is no action. "The king's seer" makes a few competent deductions — the birth of a child, the alliance of an enemy, the harshness of winter — and the king's court pivots as needed. The book's more creative antagonists, aging men of the cloth seeking glory for their name, are slowly phased out of the narrative in favor of Hild's redundant musings on the viability of her uncle's kingdom. To much surprise, there is very little actual war/conflict in this book. And while scenes come alive when Hild takes up the blade to lead a band of war hounds to settle disputes with bandits or to protect the land from purveyors from the south, two brief but meaningful battle scenes in a Middle Ages tome of 530+ pages is quite paltry. Would HILD have been more engaging if the author had leaned far less on the rigid details native to bickering lords than had shown greater interest in the consequences of said bickering? It's difficult to argue otherwise.

The book's writing, amusingly, whips about like the wind — sudden and vicious, at first, then pensive and purposeful, then quite forgetful of whence it came and to where and goes. In the first half of the title, the author layers details upon details and leaves readers with inordinately long sentences and writing that is rough around the edges. There are some paragraphs, numbering some 65 words or more, which are all but one sentence.

Another, more potent example rests in the author's horribly inconsistent depiction of intimacy. These include incoherent prophecy fulfilling trysts with a stranger smelling of dead seals; vague encounters between nameless, godlike figures before a hearth; bisexual best friends; scenes of mutual masturbation; incest; and an on-again and off-again affection between a woman and her slave.

The narrative is impractical and dense. The story dynamics are absent a meaningful balance of inciting incidents. The characters are slippery. From the first page to the last, HILD does not read like a novel but a student dissertation of pastoral Britain.

Sex, in HILD is random, awkward and drolly unfulfilling. The most hilarious (and thereby worst) example of which concludes rather blandly:

"They were naked."

All of which makes for hazardous reading. Physical intimacy means many things to many characters, surely, but the severity and clumsiness of its application, in HILD, deprives readers of the fun and peculiarity of its complexity and intrigue. Gwladus is Hild's servant and bodywoman. The young slave ingratiates herself to her mistress to further her bid for freedom. And yet, Gwladus grows so fond of her mistress that when she does obtain her freedom she declines an offer to leave. Regrettably, the book does not explore the woman's emotional fever to remain within herself beyond occasionally tempting Hild to suckle a nipple or bite her lip. Further, does Hild refuse Gwladus because the woman is (initially) viewed as property or because she fears becoming attached to another person? Readers never find out.

And so it goes. The narrative is impractical and dense. The story dynamics are absent a meaningful balance of inciting incidents. The characters are slippery. From the first page to the last, HILD does not read like a novel but a student dissertation of pastoral Britain. The clever musings on wren nests in bushes, the colors of the underside of out-of-season mushrooms and the direction cows face when they chew grass would be distractions anywhere else. HILD is not a tale of curiosity and woe and of the impressions of bygone eras. It is literature best left to mumbling academics striding the moors at daybreak.

#hild#historical fiction#review#book review#goodreads#middle ages britain#impossibly suspicious king#2 of 5 stars#redundant musings#political squabbling#good for her#impractical and dense#fears becoming attached to another person#characters are slippery#nothing of narrative consequence#natural conclusion#meaningful battle scenes

0 notes