Text

hey fellow artists I know that we all want to create huge beautiful peices with dynamic poses all the time but sometimes you just gotta draw a guy just kinda standing there. For your mental health I guess.

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

Who am I ?

#<33#How you amount to how much you’ve left an impact on people#yes!#that's a more succinct way of putting it#indeed#what makes a person is much more than the tangible#ともだち

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 91: Scoping out the scope of scope

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘Scoping out the scope of scope. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Lauren: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Lauren Gawne.

Gretchen: I’m Gretchen McCulloch. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about scope. But first, our most recent bonus episode was about inner voice, and the different ways that people organise their interior narrative – such as inner speech, inner visualisation, inner non-symbolic thought – and other ways that our minds are surprisingly different from each other.

Lauren: We look at a classic paper on inner voice, and we also include some results about inner voice from our 2023 listener survey.

Gretchen: It was fun to see how our results compared to the results of that classic survey and compare differences in methodologies and how the insides of our minds are both similar and different to each other.

Lauren: Also, on Patreon, our patrons at the Ling-phabet tier not only get all of our bonus episodes, but they get a Lingthusiast sticker, which is not available anywhere else.

Gretchen: This is a sticker that says, “Lingthusiast – a person who’s enthusiastic about linguistics,” if you want to stick it on your laptop or your water bottle and try to encourage people to talk about linguistics with you. We also give people in the Ling-phabet tier your very own, hand-selected character of the International Phonetic Alphabet – or if you have another symbol from somewhere in Unicode, you can request that instead – and we put that in your name or your username on our sponsorship Wall of Fame on our website to thank you for supporting the show.

Lauren: You can see our Supporter Wall of Fame at lingthusiasm.com/supporters, and maybe you can join it as well.

Gretchen: We also make delightful high-quality, human-edited transcripts for all of our episodes – bonus episodes and main episodes – where all of the proper names and words in other languages have had their spellings checked. Transcripts are available as text-based pages at lingthusiasm.com/transcripts or if you’d like to follow along with the audio and the transcript at the same time, you can go to our YouTube channel. Transcripts for bonus episodes are linked to from each of those bonus episode pages as well on Patreon.

Lauren: It’s thanks to the support of our patrons that we are able to continue to provide the show ad-free and high-quality transcripted.

[Music]

Gretchen: One of the best kebabs that I ever had was a philosophical kebab.

Lauren: Hm, okay.

Gretchen: I was at a kebab shop, as one does, and I ordered my kebab off the menu, and then the person behind the counter says to me, ���You okay with everything?” And I sort of had this moment of, you know, I do like to think that I’m a relatively accepting person, but there are some things in life that maybe I’m not okay with.

Lauren: Um, is it just that they wanted to know if you wanted tomatoes and hummus and onions?

Gretchen: Yeah, yeah, that’s what they were asking me.

Lauren: Reminds me of the everything bagels in Everything Everywhere All at Once where the everything bagel eventually takes into it everything across the multiverse.

Gretchen: So, not just sesame seeds and poppy seeds and dried onion bits.

Lauren: No, a little bit more “everything” than a traditional, physical everything bagel.

Gretchen: You know, it’s funny that “everything” in the context of a kebab and “everything” in the context of a bagel are different from each other. This also reminds me of a very nice poem by Shel Silverstein which is about a hot dog.

Lauren: Can I hear it?

Gretchen: Yeah. “I asked for a hot dog / With ‘everything’ on it / And that was my big mistake, / ’Cause it came with a parrot, / A bee in a bonnet, / A wristwatch, a wrench, and a rake. / It came with a goldfish, / A flag, and a fiddle, / A frog, and a front porch swing, / And a mouse in a mask– / That’s the last time I ask / For a hot dog with ‘everything’.”

Lauren: So good – and not dissimilar to one of the main plot points in Everything Everywhere All at Once.

Gretchen: Which is great. We’ve had hot dogs and bagels and kebabs, and the set of prototypical toppings for them, I mean, could include onions in any case but definitely includes lots of other things as well. And yet, a goldfish, a rake, a parrot, a frog – not typical toppings for any of these food items.

Lauren: I think we should open a café with all of these ambiguous “everything” foods. What should we call it?

Gretchen: We could have everything bagels, hot dogs and kebabs with everything, like an everything pizza. I think we could call it the “Everything Café.”

Lauren: Ah, yeah. We actually have a different phrase in Australia. We can order things with “the lot.” You can get a pizza with the lot; you can get a burger with the lot. It means it comes with the full set of expected items – no goldfish, typically.

Gretchen: There is a certain irony to the fact that in Canada we also have a phrase that’s different from “with everything,” and that’s “all dressed.”

Lauren: Ah, but is it all dressed with –

Gretchen: No goldfish.

Lauren: But is it all dressed with a flag and a fiddle?

Gretchen: No goldfish, no fiddles. But you can have all dressed chips, which is the flavour that has a bit of barbeque and a bit of sour cream and onion and a bit of ketchup, and it’s just got all of the stuff.

Lauren: All dressed chips are delicious – just, like, generically salty delicious.

Gretchen: You can have an all dressed pizza, which is a pizza with the typical expectation of pizza toppings. Again, no fiddles. In French, “tout garnis” which is also perhaps a literal translation – I don’t know which direction – of “garnished with everything.”

Lauren: Hm, yes. Of course, what counts as “everything” varies across items and across cultures because Australia famously loves some beet root in a burger with the lot.

Gretchen: Ah, yes, whereas my all dressed burger does not contain beet root, although I understand it’s delicious.

Lauren: It is delicious, indeed.

Gretchen: Both “everything” and “all dressed” and I assume, also, “the lot,” have something important in common, which is this idea that they include “all,” but “all” within a culturally-defined set not everything possibly conceivable and that we have a set of expectations for what we mean around that “all” or that “every.”

Lauren: Knowing where that “all” stops creates issues with what the scope of “all” includes.

Gretchen: Right. We have expectations around the scope of what goes on a pizza or the scope of what goes on a hot dog, but those are implicit.

Lauren: Maybe we should call it the “Scope Shop” for our café.

Gretchen: Ooo, “The Scope Shop,” “Ye Olde Scope Shop.”

Lauren: /skoʊp ʃoʊp/.

Gretchen: “Shoppe”? Oh, and then can we have a Medieval bard at our Scope Shop?

Lauren: Uh, I’m not sure why, but given this is all hypothetical, pitch me.

Gretchen: Well, it’s because the Old English word for an oral poet or a bard was /ʃɑp/, which was pronounced like “Scope Shop,” but it’s spelled S-C-O-P. It’s like halfway between the two, so then you can have a “Scope Shop Scop.”

Lauren: Right. This is ambiguous in terms of which word you’re using, which is very different from the kind of ambiguity we’re gonna be looking at with “everything.”

Gretchen: This is the ambiguity that has to do with which word you mean or what a specific word means rather than ambiguity that’s inherent to the concept of “everything” that it includes an expected set.

Lauren: When it comes to grammar, it’s not just words like “everything” and “the lot.” This kind of ambiguity pops up in a bunch of places in grammar, and that’s what’s on the menu for today.

Gretchen: Mm-hm. Can we also have at the Scope Shop customised birthday cakes?

Lauren: Sure, why not.

Gretchen: I’m gonna get you to write a message for me on the cake, okay?

Lauren: Okay, sure, what would you like on your cake?

Gretchen: I want it to say, “Happy Birthday.” Underneath that, “We love you.”

Lauren: Okay. I’m gonna decorate a cake, and it’s gonna say, “Happy birthday underneath that we love you.”

Gretchen: Yeah, well, what I want is for it to say, “Happy birthday.” UNDERNEATH that, “We love you.”

Lauren: Great. “Happy Birthday. Underneath that: We love you.” Eight words. We should be able to fit that on a cake.

Gretchen: No, I don’t want the WORDS “underneath that” to be on the cake. I want the words “We love you” to be literally underneath the words “Happy birthday.”

Lauren: Oh, like, “Happy birthday. We love you.”

Gretchen: Yes.

Lauren: I mean, it’s fine, but it’s not as funny.

Gretchen: See, you do see this on various pictures that go around the internet of very literal cake decorations. You know, “Happy birthday, Kevin, in red text,” where the “in red text” is also literally written on the cake or something like that.

Lauren: There’s a running series of jokes in this vein from BoJack Horseman, which is an animates series, and the birthday banners start with “Happy birthday, Diane, and use a pretty font.”

Gretchen: So, it’s not in a pretty font. It’s “and use a pretty font” is on the banner.

Lauren: Yes.

Gretchen: Okay.

Lauren: And the next one is “Congrats Diane and Mr. Peanut Butter. Peanut Butter is one word.” Again, all of it on the banner and, for some reason, they went back to the same supplier despite two years of failed banners because –

Gretchen: Rookie mistake.

Lauren: – the next year is “Congrats Diane and Mr. Peanut Butter. Mr. Peanut Butter is one word and don’t write one word.”

Gretchen: Oh, no, I love it.

Lauren: And then at some point, I think it’s probably Mr. Peanutbutter is wearing a t-shirt that says, “I had a ball at Diane’s 35th birthday, and underline ball. I don’t know why this is so hard.”

Gretchen: Again, the shirt says, “I don’t know why this is so hard.”

Lauren: Yes. Someone is taking down a quotation and is deciding to misinterpret a re-reading of “Oh, yeah, they said on the t-shirt put ‘I had a ball at Diane’s 35th birthday, and underline ball, and I don’t know why this is so hard’.”

Gretchen: Sounds very normal to me. I mean, this is how you can tell that they were ordering these banners and these t-shirts and so on and these cakes over the phone or potentially in conversation and not in written English, for example, because then you would just have a text field, and you could use punctuation to convey what you want on the cake.

Lauren: I mean, in spoken language we use our intonation, and in signed languages we can use the sign space, so where we sign something to indicate the start or the end of something that is being quoted. But misinterpretations can arise, and that’s where we get these hilarious cakes and banners.

Gretchen: I always think of this in context of the CBC, which is the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, where I remember as a child hearing CBC radio announcers saying things like, “The prime minister said, quote, ‘Blah blah blah,’ end quote” – or actually I wasn’t sure if it was “end quote” or “un-quote.” I looked I up on the CBC website, and I actually found both in the same transcript. Oh, wait, can I do these examples for you in my CBC radio voice?

Lauren: Yeah, sure, absolutely.

Gretchen: “A senior official said, the actual number may be, quote, ‘higher than is being cited,’ un-quote.”

Lauren: I love how generic that line of media is taken out of context, but also, how snarky it is to highlight that something is “higher than is being cited.”

Gretchen: Second example. “The provincial health minister has called the overcrowding, quote, ‘not acceptable,’ end quote.”

Lauren: Amazing. There’re just two words. “Not acceptable” is in the “quote-end quote.” Because you don’t want, as a newsreader, for people to think that the next line of the news is potentially something attributed to the provincial health minister.

Gretchen: Exactly. Because they’re saying it in this very flat, modulated, not-expressive – they’re not doing a whole bunch of stuff with intonation, and they obviously don’t have gestures because they’re on the radio – so they need the formal statement of – sometimes saying, “un-quote,” sometimes saying “end quote” – to demarcate exactly where the quotes begin and end.

Lauren: That’s because once we say someone said something, that opens up the beginning of this reported scope, and without intonational punctuation, like quote marks, very helpful, but without them, it can be hard to know where it stops. That’s because in English the verb “to say” comes before what is being said.

Gretchen: I could say something like, “Lauren told me a story,” and maybe I said this ten years ago, and everything I’ve been saying since then has just been in the story you told me.

Lauren: Hmm, yes. Highly implausible, but I guess technically possible.

Gretchen: This podcast has secretly just been one of us this whole time.

Lauren: The fact that our verb “to say” comes before what is being said is not the way that every language structures its grammar. For languages that tend to put the verb at the end of a sentence, that “say” will come after the thing that is being said, and this is true for the Tibeto-Burman languages that I work with as well as many other languages in the world, but it means that you know when a quote finishes because someone will say – you know, it would be something like, “The provincial health minister, the overcrowding, ‘not acceptable,’ he said,” or something to that paraphrased effect. You know the end of a quotation. It might be ambiguous at the front end, but you know when something is finished.

Gretchen: Despite how English verbs normally work, with “said,” you can put it at the end of a sentence. There’s a whole style of joke in English that depends on putting the verb towards the end. They’re known as a Tom Swifty. By convention, they’re always attributed to a speaker called “Tom.” You have a statement something like, “‘If you want me, I shall be in the attic,’ said Tom, loftily.”

Lauren: And the way that Tom says something is always a hilarious pun on the content of what is being said. Yeah, that is a great example of –

Gretchen: Like “attic” and “loft.” It wouldn’t be funny if you said, “Tom said loftily, ‘I shall be in the attic’.” Actually, maybe that’s still funny because it’s just the connection between the two.

Lauren: But not as funny to have the punchline delivered at the end.

Gretchen: Yeah, exactly.

Lauren: Of course, even though languages that have the verb, say, at the end of the sentence, they also do the thing English does where we just report something without saying, “They said.” There is still the chance for ambiguous cake decoration to occur.

Gretchen: It’s very important to be able to have funny cakes. Those cake examples of scope in quoted speech are this humorous misinterpretation of something that someone says that someone else writes down. There’s also another way that you can use scope to get multiple readings. This is with negation.

Lauren: Oh, yeah, that’s another fun place for scope ambiguity.

Gretchen: In this case, you can get one sentence that itself has several meanings depending on how you interpret the negation.

Lauren: For example, a bench in honour of Nicole Campbell, it’s engraved with a little plaque, and it says, “In honour of Nicole Campbell, who never saw a dog and didn’t smile.”

Gretchen: This photo of this plaque on this bench went around the internet a while back. People found it really funny because you have this very obvious humorous reading, which is she refused to look at dogs and also wouldn’t crack a grin.

Lauren: Which is a very cantankerous anti-dog stance that is clearly the opposite of what was actually so wonderful about her.

Gretchen: And clearly the intended reading is “It was never the case that when she saw a dog she didn’t smile at the dog.”

Lauren: And, I assume, in this park, at this bench or somewhere proximal, this would often occur.

Gretchen: Right. Maybe it was a dog park.

Lauren: Instead, what you get is like, “She refused to look at dogs and she never ever smiled at all in her entire life.”

Gretchen: Or she lived on an island where there were no dogs at all.

Lauren: I mean, that’s why you wouldn’t smile.

Gretchen: Because there’s no dogs there.

Lauren: Sad times.

Gretchen: What a tragic bench plaque of this horror life that this person lived. It’s so tempting to get that reading.

Lauren: We’re commemorating a tragedy there.

Gretchen: It’s really important to have memorial plaques like this. If we think of “never” as popping up a little umbrella over some part of the remainder of the sentence, then the parts that get shaded by that umbrella are within the scope of never, and the parts that are still out in the open to get rained on or sunned on are the ones that are outside the scope of “never.”

Lauren: We have one reading where there’s a really narrow scope of how big the umbrella for “never” is, which is just “never saw a dog,” and then “didn’t smile” is out with its own narrow little umbrella. So, “never saw a dog” and “didn’t smile” – poor, grumpy Nicole. Then we have a really broad umbrella where “never” fits over the whole “saw a dog and didn’t smile.” “Nicole Campbell, who never saw a dog and didn’t smile” – a really big umbrella. It can all stand under it, and we get this very different reading.

Gretchen: I like how you’re doing very helpful gestures right now that nobody can see.

Lauren: It’s for my own cognitive processing.

Gretchen: Make sure you do the gestures when you’re listening as well. This is my suggestion. The thing that I like about scope as a phenomenon is that it’s one of those things that pops up as you’re going about your life if you’ve got your little linguistic lenses on and you’re analysing sentences as you see them. This means that linguists will often have a little pocket full of examples of scope and scope ambiguity. When we were preparing for this episode, I was having dinner with some linguists, and I said, “Hey, anybody have some favourite examples of scope to share?”

Lauren: I’m glad that you’re making it clear this is genuine thing that we enjoy doing is asking people for their favourite examples of scope.

Gretchen: Please send us examples of fun linguistic phenomena. One of them said, in the women’s bathroom in the Georgetown linguistics department – this is an important part of linguistic cultural history – there was a sign that said, “Please make sure to flush. Automatic sensor doesn’t work 100% of the time.” The two readings there – which took me a second because they’re a little bit less funny than the “never saw a dog and didn’t smile” example, I will admit, but the fact that it was found in the wild, you know, has some benefit to it – one is it’s not the case that it always works, so maybe it only works 90% of the time not 100% of the time, which is what the person writing the sign presumably intended.

Lauren: But there’s also a reading that’s like, “It doesn’t work 100% of the time – 100% of the time, this thing does not work.” It is a very bad automatic toilet flush.

Gretchen: Exactly. Might as well not even be there. Somebody had written, apparently, “scope ambiguity hee hee” on this sign in the bathroom of the linguistics department.

Lauren: I love it.

Gretchen: Because this is what we’re like.

Lauren: With negation and reported speech we have either “someone said” or we have a bit of negation that creates this umbrella that goes forward into the sentence to scope over what comes next and how much of what comes next is what can lead to some ambiguity. But I also think about that brief historical fad in 1980s English for putting “not” at the end of a sentence.

Gretchen: Is that something where you’re like, “Here’s some pizza for you – not!”

Lauren: Exactly. I think we’re gonna have to work on your customer service if we’re gonna open this restaurant, Gretchen. But that one is reaching back into the sentence and that is what makes it funny in English because we’re so used to things going forward into the sentence and scoping over what comes after it.

Gretchen: But in principle some other languages must do negation scoping back into the sentence instead of scoping forward into the sentence, just like with recorded speech, right?

Lauren: There’s lot of variation in where negation can pop up in the grammar of a language. I went to visit WALS just to confirm with some survey of a range of different languages, and even though having negation just before your verb is the most common, there are lots of languages that will have the negation right at the very end of a sentence. In fact, something close to 20% of the languages in this survey had that form of negation right at the very end. So, in those languages, it is totally normal for it to go back into the sentence that’s just been said and scope back over what has already been said instead of scoping over what is to come.

Gretchen: You could probably still get some kinds of ambiguity, but maybe a bit of a different set. Thinking about this scoping either forwards or backwards into the rest of the sentence or into the bit of the sentence that came before, it feels like less of a classic round umbrella that scopes equally over your entire body and more like one of those retractable ones at the front of the café that really scopes over in one direction rather than circularly.

Lauren: We should definitely have one at the front of our hypothetical café.

Gretchen: If you’re within the scope of the Scope Shop slope, you can still have soap? I think we’ve got to work on this menu.

Lauren: We definitely got to work on this menu. The cool thing is, if you bring in both reporting and negation, you can get some really brain-hurting ambiguity going on.

Gretchen: There’re some examples of this that you see going around on social media a fair bit because they’re really fun to do lots of different interpretations with, but also, a lot of these sentences are a bit violent or menacing.

Lauren: I think even the ones that aren’t menacing once you start reading them with different stress, which gives rise to different readings, you can’t help but find them a little bit menacing. One that goes around frequently is “I didn’t say he stole the money.”

Gretchen: Okay, let’s try reading this putting emphasis on each word one at a time.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he stole the money.”

Gretchen: Maybe this other person said it.

Lauren: “I DIDN’T say he stole the money.”

Gretchen: You’re trying to put words in my mouth.

Lauren: “I didn’t SAY he stole the money.”

Gretchen: I just showed you all the security camera footage.

Lauren: “I didn’t say HE stole the money.”

Gretchen: Maybe she did.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he STOLE the money.”

Gretchen: Maybe he borrowed it.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he stole THE money.”

Gretchen: Not that big stash of profits, just some petty cash.

Lauren: “I didn’t say he stole the MONEY.”

Gretchen: He stole the car.

Lauren: Each of these gives rise to different readings. Obviously, we can use emphasis in any sentence to change what word we’re focusing on.

Gretchen: But in this case because we have both the “say” and the “didn’t,” it puts emphasis on which parts are we negating and which parts are we reporting the speech of. In combination, that creates this very strong change in meaning when you emphasise one word versus another.

Lauren: They’re really fun. I can definitely see why when you have an example that’s so juicy in terms of the flexibility of the meanings that arise, you often see these doing little circuits on social media.

Gretchen: One of the other examples that goes around on social media pretty often is even more violent. It’s “I didn’t ask you to kill him.” You can try this exercise for yourself on this other sentence if you like.

Lauren: Of course, along with the intonation in spoken language that helps us figure out where the negation is being scoped over, we also have the gestures that we use alongside speech. There is work that shows pretty consistently that, say, maybe a headshake in English for negation or something like a pushing away or a shaking a hand in refusal tends to scope very nicely over the same bit as the grammatical negative form like “not” or “don’t.”

Gretchen: Very nice.

Lauren: We also have gestures when you are in an audio and visual context – unlike this audio-only podcast.

Gretchen: Signed languages also use non-manual markers like eyebrows and shaking head and things like that to do this kind of negation scope and make sure it’s clear when it starts and ends.

Lauren: Alongside reported speech and negation, we also have our classic everything bagel-slash-pizza menu item.

Gretchen: We can also make “everything” ambiguous.

Lauren: That is true.

Gretchen: We’ve already made “everything” ambiguous one way by talking about how much it refers to in a cultural context. We can also make it ambiguous in a more structural way by combining it with words like “some.”

Lauren: True.

Gretchen: The classic example that a lot of people encounter in a semantics class is “Everyone loves someone.”

Lauren: That could be that everyone has at least one person that they love. There might be some overlap, but there’s lots of different people getting that love.

Gretchen: Or it could mean there’s this one person who everybody loves who’s super popular.

Lauren: Oh no, that is gonna get really difficult. I feel very sorry for that someone.

Gretchen: Certain complications in fandom, and maybe they’re too popular. But “Everyone loves someone” can just as validly mean both of those things.

Lauren: Alongside “some,” there are words like “all” and “every” that create this “Exactly how much is being scoped?” ambiguity as well.

Gretchen: Right. There’s another example from the linguist I was having dinner with, which is my friend’s kid got one of those kindergarten worksheets where they have them do exercises to teach them about quantities. The instructions said, “Colour half of all the pigs.”

Lauren: There’s six pigs, and I have to colour three of them.

Gretchen: If you were the kindergarten teacher, you might have assumed that’s what the exercise meant. This kid colours all of the first pig, clearly does a lot of thinking, erases half of the first pig, and then colours half of the remaining five pigs. “Colour half of all the pigs.”

Lauren: I really got to commend that kid for their lateral thinking skills. I mean, they completed the task.

Gretchen: I think this kid has a great future as a linguist. They’d fit right in at the Georgetown linguistics department.

Lauren: Absolutely.

Gretchen: They fit right in in the bathroom of the Georgetown linguistics department. [Laughter] Then you can get really fun examples of these kinds of ambiguity with words like “some” and “every” and “all” sometimes in headlines. I remember seeing, a few years ago, “Someone’s getting a vaccine every 10 seconds.”

Lauren: We’re confused about whether we’re talking about lots of different someones or just one, single someone, aren’t we?

Gretchen: Like, “Wow! This person is gonna be so well protected against COVID, but what about the rest of us?”

Lauren: Ah, yes, that is where we really wanna be careful about whether we have a scope ambiguity or not.

Gretchen: Similarly, there was a headline that went around that was “A woman gives birth in the UK every 48 seconds. She must be exhausted.”

Lauren: Yeah, I am horrified by that one. Sometimes this pops up even with words that we don’t think of as having this kind of scope ambiguity. On social media a while ago, a baby care brand with the slogan “Caring for your baby since 1890,” and someone had just commented, “My 100-plus-year-old baby says thank you, but please let her die now.”

Gretchen: Oh no. So, not caring for your one, individual baby.

Lauren: For your one, individual baby or your generic, ever-changing baby. Gretchen, after all this scope ambiguity in reported speech and negation and words like “some” and “all,” I just wanted to ask, “Are you okay with everything?”

Gretchen: You know, some days, that might be toppings on a kebab. Some days, that might be the entire universe. I’m okay with everything that’s in the scope of this episode, and that’s enough for today. But no onions.

[Music]

Lauren: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on all the podcast platforms or lingthusiasm.com. You can get transcripts of every episode on lingthusiasm.com/transcripts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on all the social media sites. You can get scarves with lots of linguistics patterns on them including IPA, branching tree diagrams, bouba and kiki, and our favourite esoteric Unicode symbols, plus other Lingthusiasm merch – like our new “Etymology isn’t Destiny” t-shirts and aesthetic IPA posters – at lingthusiasm.com/merch. My social media and blog is Superlinguo.

Gretchen: Links to my social media can be found at gretchenmcculloch.com. My blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com. My book about internet language is called Because Internet. Lingthusiasm is able to keep existing thanks to the support of our patrons. If you wanna get an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month, our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now, or if you just wanna help keep the show running ad-free or get a cool sticker in the mail, go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm, or follow the links from our website. Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk to other linguistics fans and be the first to find out about new merch and other announcements. Recent bonus topics include inner voice, how to make a vowel chart – with Bethany Gardner – and an episode where we took the “What Episode of Lingthusiasm are You?” quiz. Perfect for picking a starter episode for a friend or deciding what to re-listen to. Can’t afford to pledge? That’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language.

Lauren: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins, and our Editorial Assistant is Jon Kruk. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Gretchen: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

@originalaccountname SNOOZER

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

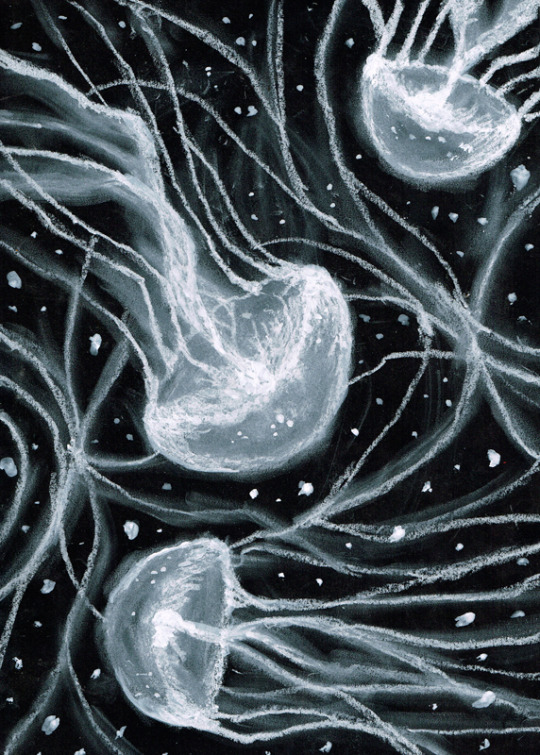

Desar (destruction) from TMA by @we-love-you-star-child

#ともだちがかいた#oc art#sparky#oh the sense of destruction is indeed present#and the blue and red#you know how veins are blue and arteries are red#it feels like everything’s being torn apart and dissolving away

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who am I ?

#oh#indeed who are you#who are any of us#what are we#what makes up a person?#hm this feels like it’s once again linked to something faye said#like after one passes#is that person gone?#when we say something like x would have been 100 years old this year can we also say x is 100 years old even though they’ve passed#in the physical sense#because once a person comes into existence do they ever really die as long as they’re remembered#or some record of them remains#like how you’d say a tradition is how old or a theory is how old or a song that’s never been written down is how old#yet another tangent#oc art#sparky#delphi#doodles#ともだちがかいた

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you name all the palindrome days ? :3

all of the ones this year, all of the ones I've covered, or all of the ones up to this point in time, including the rest of this year? because those are three very different posts

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

“One of the most solid pieces of writing advice I know is in fact intended for dancers – you can find it in the choreographer Martha Graham’s biography. But it relaxes me in front of my laptop the same way I imagine it might induce a young dancer to breathe deeply and wiggle their fingers and toes. Graham writes: ‘There is a vitality, a life force, an energy, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all of time, this expression is unique. And if you block it, it will never exist through any other medium and it will be lost. The world will not have it. It is not your business to determine how good it is nor how valuable nor how it compares with other expressions. It is your business to keep it yours clearly and directly, to keep the channel open.’”

— Zadie Smith (via campaignagainstcliche)

25K notes

·

View notes

Text

“it would be lovely to sleep in a wild cherry-tree all white with bloom in the moonshine,”

— L.M. Montgomery, from “Anne of Green Gables”

454 notes

·

View notes

Photo

— Aure Vives, ‘Soul beloved’

5K notes

·

View notes

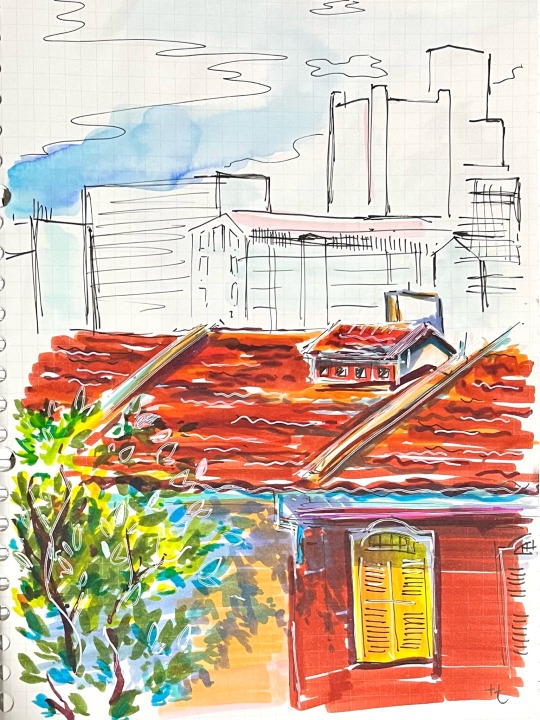

Text

adding on to that,

we got approached by some students doing a survey. sadly we had to turn them down because they were looking for foreign tourists

but! it was funny because we’d been asked at a store earlier where we were from, so we were kinda slowly feeling like tourists and trying to figure out what we could possibly pass off as (the conclusion was… not exactly anything that we’re not)

this box of chocolates was rather cute too. imagine having enough to play

and this shop! the aesthetic reminded me of my old bedroom

#and we had $9.90 ramen#$9.90 excluding gst + service charge#which was not bad actually#the ramen noodles were the instant noodle kind of ramen but the soup was really nice#the meat was also pretty good. on the salty side but nice#I’d do that again#oh and we got little cups!#with koi fish!#ttee_journal#ttee_tft

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

there's a lot to hate but i think my least favourite thing about AI generated images is that now every time i see a really cool artwork on the internet, instead of childlike wonder i experience suspicion

1K notes

·

View notes