Text

No, 70%-85% of People DON’T Get a Job Through Networking

(Date published/updated: March 2023)

At Least, There’s No Reliable Data to Confirm That

There's a very misleading statistic that frequently gets bandied about in the job-advice world: 70%-85% of people get their jobs through networking. Type that into Google and you’ll get tons of articles (some from fairly reputable sources like Forbes, CNBC, Yahoo, and NPR) repeating it. However I was skeptical when I heard this data point, and I was right to be, turns out.

Let’s dive into this.

There seem to be two main sources for this apocryphal statistical truism. One is a 2016 survey published on LinkedIn. This is the primary source widely cited in outlets like Forbes and Yahoo (linked above), all the way down to business and career blogs and sites like FinancesOnline. Ironically, FinancesOnline cites that statistic by linking to a HubSpot piece which no longer exists. The Hubspot “original source” page has been taken down (though it was quite likely citing the LinkedIn study)

However, that LinkedIn data is DEEPLY suspect. For a full debunking of that research, scroll down to section 2 below.

But before getting into more detail on why that 85% number is bogus, it is also worth talking about the (long) history of that 70%-80% stat. It has been shared fairly recently on outlets like CNBC (linked above); but the most commonly linked-to source on it (that I can find) is a 2011 NPR piece. The data doesn’t come from any cited or mentioned social science research, or any other kind of actual statistical finding.

It is shared with NPR in an interview with a man named Matt Youngquist, who is the president of Career Horizons, which, according to their website “specializes in providing professionals with expert advice in improving their job hunting and career success.” In other words, they are career consultants who get paid to help people do things like network. Youngquist shares the stat, but gives no information on the source of it (nor does NPR do any due diligence on it). Youngquist just repeats it, and NPR publishes it, like so many before them have done.

It’s a commonly circulated percentage, but one that appears to be without any real basis, at least not in this century. A few folks have done some digging on this, and best anyone can tell, that 80% stat became widely circulated after an 1980s New York Time’s piece quoted Richard Bollen (of What Color is Your Parachute fame) as saying 80% of jobs are not acquired through “formal means” (which includes job applications) (h/t to Jen Hubley Luckwaldt at The Balance Careers for helping to dig this up, citations and all)

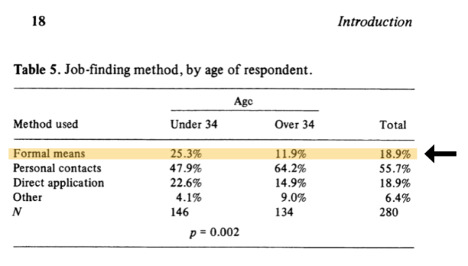

Bollen’s source of that information appears to have been research conducted and published by Harvard Sociologist Mark Granovetter in the 1970s!!! Granovetter wrote a paper called “The Strength of Weak Ties” and later a book called How to Get a Job (first ed. 1974, second 1995). In How to Get a Job, Granovetter includes data such as the chart below (p. 18)

I’m not going to dive into the study in-depth because it’s from 1974 and therefore obviously totally irrelevant to the modern job market, regardless of its validity at the time. However, the 80% figure that Bollen popularizes in the New York Times appears to have been derived from this data, which found that roughly 19% of the job seekers included in Granovetter’s study found a job through “formal means,” which included answering a job ad (it also included use of other formal, 3rd party institutions like recruiters).

Ironically, even this data does not say 80% of people got their jobs through networking. While a little less than 20% got it through ‘formal means’ (including job applications) another near 20% got it from just sending resumes cold, calling cold, or walking in. That’s what “direct application” means here. That 80% statistic has become very distorted in present-day conversations about job hunting (because virtually no one who uses it actually knows where it came from!). And it is almost 50 years out of date at this point.

So if you are a job seeker, do not take any of that data seriously. And if you are in the job advice sector STOP REPEATING IT. It’s completely out of date and has been highly distorted.

Now, on to debunking that study published on LinkedIn….

SECTION 2

Don’t trust that 85% number either.

FIRST, THE STUDY IS FAIRLY DATED

Although 2016 is not nearly as out-of-date as 1974, it is dated as far as the job market is concerned, due to COVID and a number of other factors. But even if the study were current, it is not valid or reliable for a whole host of other reasons, such as…

SECOND, NO SAMPLE INFORMATION IS GIVEN

In his write-up on the data, the author states: “About 3,000 people have responded so far, most of whom are in staff or management roles.” That’s the only information he gives about WHO the respondents were.

There is NO demographic information provided (no age breakdowns, no gender breakdowns, no racial/ethnic breakdowns, no regional breakdowns, etc.) We have no idea who makes up this sample, so there’s no way to verify if it is remotely representative of…anything. (It is worth noting, the survey itself doesn’t even ask for that info, so even the author has no idea what his survey demographics look like)

Furthermore, we have no idea what sectors these people currently – or formerly – worked in. Certain sectors rely more on networking than others, and this survey could be skewed towards networking-heavy sectors. (Or it could be skewed in the opposite direction, but the point is, there’s no way to know or verify that)

THIRD, THERE’S A STRONG LIKELIHOOD OF SAMPLE BIAS

The author starts the piece by saying “Over the past 12 months I’ve been asking people how they found their most recent job.” That’s the only information he gives about how his sample was acquired. My suspicion is it was mostly circulated through his own personal networks, and on LinkedIn…which is a site primarily for professional networking!!

This is a textbook example of (likely) sample bias. Quite probably, he gathered his sample from a place where the most active members are highly invested in professional networking. It’s like going on the DC Comics subreddit and asking how many people like Batman. The sample source is going to skew that data a LOT.

(And granted, we don’t KNOW it was distributed on LinkedIn, but the fact that it’s not clear where or how he got the sample should be enough to make this 85% statistic meaningless on its own)

But never fear, there’s even more BS where that came from….

FOURTH, IT HAS VERY QUESTIONABLE DATA REPORTING

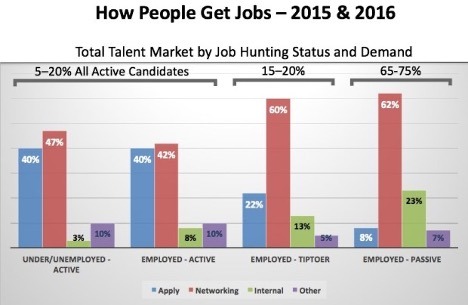

Very early on in the piece, he shares a graph, which divides the job ‘transition’ sector into four groups:

Active jobseekers who are un/under employed

Active jobseekers who are employed

“Tip-Toers” (people who are casually poking around, but not making a full-throated effort)

Employed “Passives” (people who are not job-seeking, but who nonetheless find new jobs through other means, mostly networking)

There are several troubling things to note about this graph. First the vast majority of the sample (65-75% of it) falls into the “Passive” category…i.e., PEOPLE WHO WERE NOT LOOKING FOR NEW JOBS OR ACTIVELY SUBMITTING JOB APPLICATIONS. These are people who mostly changed jobs because someone in their network reached out to them to proactively recruit them (with internal openings at their current company making up the second largest chunk).

When you aren’t actively job hunting, OF COURSE the main way you are likely to change jobs is through your network contacts reaching out to you. It’s basically tantamount to saying: people who aren’t submitting job applications don’t typically get jobs by submitting job applications. Wow, useful static. Super informative.

And please keep in mind, this group makes up 65%-75% of his total sample! That 85% number was derived MOSTLY from ‘passive’ job-transitioners who weren’t actively looking to find a new job in the first place.

Only 20% (maximum) of the people included in this study (groups 1 & 2) were very actively submitting job applications as a means of finding a new job. And of those people, typically their success rate with job applications (vs. other means) was around 40%. Furthermore, for neither group does networking have an above 50% success rate for finding a new job, either. (The extra 13-18% was people finding new jobs through some means other than traditional job applications OR networking)

FIFTH, IT'S NOT CLEAR WHAT 'NETWORKING' MEANS HERE

One of my perpetual gripes with the discourse around "networking" as a job hunting strategy is it's often profoundly vague. "Networking" is a term that could mean anything from getting a wholly nepotism-based job offer directly from your aunt, to doing informational interviews, to hearing about an opening at your friend's company through a casual conversation with your friend, to seeing a call for applications on Twitter, to just having a LinkedIn profile and keeping it up to date.

"Networking" is an ill-defined concept, it can encompass a huge range of things, and it's also NOT mutually exclusive from sending in job applications. (You could learn about an opening through networking, but apply to it like a normal job, and both aspects of the process might have been necessary for you to land that job)

Most of the widely circulated data on job hunting is moderately trustworthy at best. And it is often hard to know what people are including under the umbrella of "networking" in their data. Which is another reason I take most of it with a huge grain of salt.

DEBUNKING SUMMARY

In conclusion, even assuming the demographics of this sample are representative (which is a huge leap of faith on its own), and even assuming these trends still hold true in 2023 (another leap of faith), for ACTIVE job hunters, applying to jobs versus networking has a roughly equal success rate, by this study’s own data!

***

Please be skeptical of the truism that most jobs are primarily gotten through networking. That assertion simply is not backed up by the data. At least, not the data networking advocates often cite. That 85% number is not reliable and that fluctuating 70%-80% stat is almost 50 years out of date and has been highly distorted in its circulation over the years.

(By the way, if any of you out there are still teaching undergrads, this is a pristine case study on the way statistics can become misused, distorted, and thoughtlessly repeated, even by fairly reliable sources like NPR)

1 note

·

View note