Text

Deep Listening

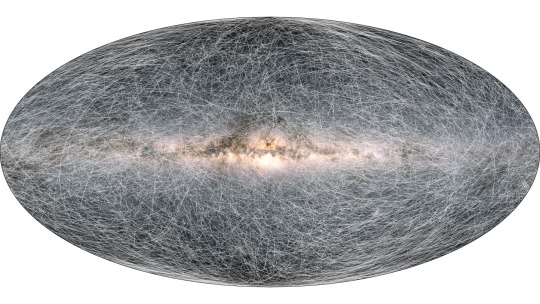

[a 3D “map” of the Milky Way galaxy, recently published by NASA - https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/12/03/1013001/this-is-the-most-precise-3d-map-of-the-milky-way-ever-made/ ]

This is my last blog post for this collection meanderings on of Ambient Language, and I’m doing a lil free-write on symbiosis, mushrooms, climate change, and how all of this ties in to communication.

I would say that symbiotic living is, in itself, an act of communicative exchange - even if on a microbial or subconscious level. Our cells interact with and exchange hormones, nutrients, waste, and amino chains with each other in a constant act of communication in order to shape our bodies and create vessels for our sense of self. Root systems underneath the forest floor are connected by mycellium, exchanging chemical compounds, moisture, sensory information, and nutrients, things which provide tells about changing seasons, roaming life forms, the health of surrounding plants. Water both inside of all living beings and outside of us, are pushed and pulled by the astrophysical forces of our surrounding moon, planets, asteroids and sun - visible in the rings of trees and tidal rhythms of our oceans. All things interact, transform, exchange - and thus, communicate.

If all things have a form of sentience, we must ask what the intelligence is of our planet’s changing climate - what information is it giving us, what is it responding to? Or of this passing virus, SARS-CoV-2, or COVID-19 - entering our bodies, changing them - changing our culture, our minds, our sense of reality. What are we learning, how are we changed, what are we given by this dis-ease?

I think our responsibility to decolonizing language and communication is to understand the shape and role of listening, and expand what it is we are listening to and for beyond language. Just like how in any conversation, my words are changed by my tonality and the movements of my body, by your perception of and relationship to me, by all that has informed meaning in these words to you - we must also treat our many interconnected ecologies this way in order to listen, deepen relationship, and create collaborative and meaningful symbiotic exchange.

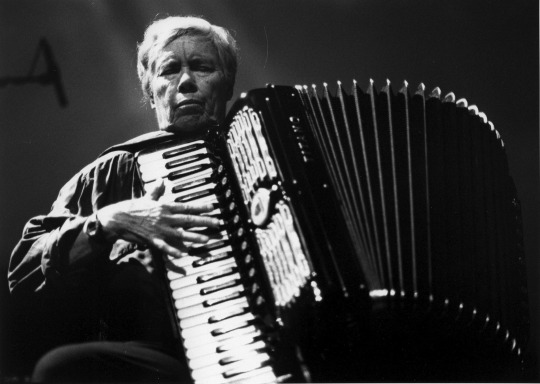

I think I will close this out with a bit of reverence for Pauline Oliveros - a great teacher of the art and practice of deep listening - https://www.deeplistening.org/ - who’s work is one of constant learning through new ways of interacting with one’s environment, and who has deeply influenced my perception of communication, and inspired this dive. May she rest peacefully <3

https://youtu.be/WvP4MxvFpP0 <This is a short video from the Whitney with Pauline, talking about her work and process

1 note

·

View note

Photo

As we talk about post-humanist communication, or ideas of decolonizing our conception of communication, I have to also bolster the movement toward reviving Indigenous languages. I don’t know my tribal language, and it’s a part of my grief of colonization to know that the way I think, perceive, define, and order my life - something shaped by language - is influenced by the loss of language we have faced through colonization.

Currently, as we globally navigate COVID-19, many efforts toward language revival are under threat. As momentum in North America has built to revive lost languages of indigenous tribes, nations are also grappling with the health and life of our elders - those who still hold the language to pass down - being under immense threat. Many tribal nations received body bags from the United States government, instead of the aid that was promised. There has been conflict on much of treaty-protected land, where hunters and tourists have wanted to enter, often unmasked, bringing this devastating disease to tribes who’d been doing everything in their power to keep isolated, and safe from COVID.

I say all this to note that it is incredible to see the resilience of different nations who continue to fight for the health of their communities, especially their elders, and alongside for the right to continue reviving and reconstructing lost or dying language.

The way we communicate linguistically changes our perception of communication itself; words hold an inordinate amount of power over our ability to transcribe and understand reality. In this way, it is deftly important to pursue the revival and reconstruction of language, especially for colonized and indigenous peoples. As artwork is a form of communication, it influences how we relate to the process of creating as well.

In a recent and incredibly thorough study, We Have to Hear Their Voices, by the Canada Arts Council, this was related to how indigenous artists process their own work;

“It is worth noting that responses to the question which asked how Aboriginal languages are used in art practices were far greater than when people were asked to describe in which artistic discipline they worked. Respondents appeared more likely to describe the “how” aspect of art practices, as opposed to “what” discipline they identified with. For example, few references were made to involvement in the visual arts, yet when asked how, several respondents made references to drawing, painting, or beadwork. This may have something to do with difficulty expressing oneself in the “language” of the Western world, as alluded to previously. Clearly, many of the older languages would not include concepts or vocabulary captured in modern disciplines, such as “visual art” and “opera.” As noted in the Preface, many Aboriginal languages have no word for “art.” Therefore, it may be inferred that it would be difficult within a culture that approaches life holistically—where all of nature imbues spirit—to isolate art practices to one particular discipline. Concepts may, therefore, be expressed in several disciplines, as all are connected or have some relationship.”

We Have to Hear Their Voices PDF

The authors go on to say that, “language forms an identity that is inextricably linked to the cultural life of the people—in the songs, dances, and spiritual ceremonies. It runs through the blood: it is in the collective memories of the people.”

0 notes

Photo

Linguists are teaching their dogs to talk and it’s gr8 <3

I’m sure you’ve seen Bunny’s journey of learning to speak on the Tik Tok account, @what_about_bunny - a dog owned by a linguist, who’s using tools for speech therapy to give Bunny a voice. Another dog, Stella, has her learning journey documented here - https://www.hungerforwords.com/

This isn’t the only experimentation with dogs and speech, however, and for centuries we’ve known Huskies and Wolves to mimic our languages with their own voices when raised in proximity to humans. This has been consistently written off as a parroting of language, not true speech - however, research is now finding that even parrots and other mimic-cry birds do associate meaning with the words they speak. This challenges the idea of the animal automaton, or soulless anima which has been pushed into western conscious conception of animals since the renaissance era.

I don’t know that I have much more to expand upon here, except that like.. well duh, of course animals have self conception, awareness, emotions, and language lol. Let’s return to the re-indigenizing and de-colonization of nature for a moment - where indigenous peoples have always believed in a non-heirarchical symbiotic relationship with our sentient siblings. It makes me think of the water experiments in which a scientist spoke to water with negative or positive intentions, and the water’s structure became more or less symmetrical and “beautiful” depending up on the language and intention used. Even our non-vocalized sentient siblings receive and respond to language, and likely communicate with us in ways we do not grasp or comprehend.

0 notes

Photo

Intuitive Knowing and Indigenous Communality with Plants, Animals, and Objects

Today I’m drawing inspiration from Gregory A. Cajete, Ph.D. who’s work in Indigenous studies, arts and sciences spans over many years. I’m currently reading his book, Indigenous Community, and was inspired by this quote:

“Natural communities are the most elegant and long-lived examples of sustainability. Learning from them is not about anthropomorphizing - giving human qualities to - natural communities, which is a common misconception of Indigenous knowledge about the natural world. Rather, it is about drawing insights from living systems and then applying them to human ecologies. Historically, this is what Indigenous Peoples did to build our communities on stable foundations.” (p. 78) and “Indigenous Peoples created our communities in earlier times by modeling them on natural communities. We mimicked the properties of ‘complex adaptive systems’ in nature - the natural communities with whom our ancestors interacted... Knowledge gained from studying complex adaptive systems in the natural world can help us understand how human social communities evolve and change over time.”

I think often we miss the holistic way of communication between Indigenous Peoples and their environment, their ecological space, and their communities. It is not a modality of communication we are used to in western society - but one of deep listening (as dubbed by Pauline Oliveros!) Communication happens when we see the other, observe and learn its ways.

In my arts practice, I engage with the consciousness of my materials, simply by creating spaces where I can observe it’s properties, and over time understand what the materials themselves have to communicate. I act in collaboration with it, in a dialogue in a sense - where I create a vessel of expression for all of us to interact. It’s not that I “speak” to my materials as we understand communication in a western society, but that I observe the material, and intuitively listen to it’s desires and my desires - urges that are sent from the earth, from the body, from the vessels the materials rest in, from the environment. We are all giving and receiving, and in Indigenous culture as I understand it as a 21st century Indigenous person living outside of Indigenous communities of the past, giving and receiving is communication.

Something as simple as gaining knowledge from observing the actions and urges of plant life, from interacting with it energetically and observing the ways in which its proximity affects us internally, is an act of communication. The plants affect on us tells us how it might interact with our bodies if consumed, and observing its waxing and waning cycles of growth tells us when and how and how much to harvest from it. This is an act of communicating with out words, held together by a deep communal concern for the fate of the other.

In indigenous communities, we don’t simply consider other humans our community - but rather an entire ecology of place and being. Including the tools and materials we use, the plants and animals who we interact with and share space with, the passage of time, the changes in weather. In this way, all things are considered as both individual and communal. As Gregory states, “All plants and animals occupy a niche in natural communities... the role that each performs are important to the overall health of the community.” There is less of an idea of separation - which is not to do with anthropomorphizing the surroundings, but rather being an integral part of a whole system that communicates in ways beyond human linguistics.

In many indigenous cultures, medicinal and psychoactive plants communicate with us through our ingestion of them. Their effects on our bodies and minds are their teachings, and consuming them is an act of receiving and communion. This is true of medicinal plants, psychoactive and hallucinogenic plants, as well as water and food. Ingesting and assimilating these things and being subtly changed by them is an act of communication.

0 notes

Text

Plant Communication Technologies

In the past few years, artists, scientists and tech nerds have all experimented with plant communication. It was recently discovered that plants communicate with the external world through electromagnetic currents, and natural processes of biochemistry in order to express thirst, to attract specific insects that protect it from harm, and to stimulate processes with other plants.

Microsoft’s artist in residence program hosted Helen Steiner’s Project Florence in 2015-16 https://coolhunting.com/tech/project-florence-microsoft-research-talking-to-plants-communication/ In this project, Helen and supportive team monitor multiple factors in comparison to stimuli translated from words and phrases common to gardening, in order to give the plant “language” and allow for a dialogue between the viewer and the plant. Leslie Garcia’s 2013 project Pulsu(m) Plantae https://vimeo.com/62232734 translates plant response to stimuli into musical patterns. More recent project, Landscapes https://vimeo.com/303567928 translates bacterial growth into synthesis based music and visualizations.

As we continue to experiment with technology in order to find common ground with plants, it is also important to note that intuitive plant communication has been in practice for millennia among cultures globally. As biologist and herbalist Stephen Buhner states in his book, The Secret Teachings of Plants, “By locating our consciousness in only one biological oscillator, the brain, we blinded ourselves to perceptions that have been common to human beings since they emerged from this Earth. In gaining a reductionist understanding of the world, we lost touch with the essential nature of the Earth and ourselves.” Interestingly, the sciences only lead us back to these intuitive understandings of plants. My grandmother, a master gardener and biologist, has always taught her students to listen to our plant companions. That when we think of watering them, they are giving us the signal to do so. This has been confirmed by scientific study - that plants, when parched, will send out a signal asking for water.

Indigenous and intuitive herbalists and shamans describe their practices of intuitive communication with plants quite clearly - that the plants quite literally speak to them, to tell them of their healing properties. In the Amazon for instance, there are 17 different species of Ayahuasca. When asked how they differentiate the species, indigenous Amazonians stated that “they each sing a different note on the full moon.” https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-76720-8_11 Many indigenous shamanistic practices speak of the song of plants, and modern western intuitive and spiritual herbalists describe the same experiences.

#plantsentience#plantlove#herbalism#intuitiveherbalism#indigenousmedicine#plantmedicine#plantcommunication

0 notes

Photo

This is a blog dedicated to exploring the ways in which we communicate across the bounds of species, of language, or even of perceivable sentience via facialization, anthropomorphism, movement, or sound. It’s inception is for a class called Post-Nature: Art in the Age of the Anthropocene at SAIC.

For at least 5 weeks, I’ll be accumulating some lovely thoughts for the tumblr ethers, accompanied by some relevant or completely irrelevant memes, because: Memes are the most relevant and accessible media art form of our TIME, change my mind lol

Who am I?

I’m an artist (www.feralorde.com), mutual aid organizer (www.swopbrooklyn.org), and criminalized s3x worker. I’m gender liminal, disabled & neurodiverse, mixed indigenous Quileute and diasporic Rromani, United States-ian currently living in Brooklyn, NY and many other less nameable things.

Why did I choose this topic?

When I think about the trauma of my ancestry, I often think of language. Language shapes the way we think, perceive, relate - it shapes the epistemology of our minds. English is my first language, and I feel mostly proficient with it when I’m in the practice of it - but I’m the type of person who does not have an inner monologue - I am dyslexic, and synesthetic, and autistic - my mind is more of a shapes, colors, textures, and images type of mind. It’s hard for me to sink into reading or writing, but once I do it’s calm and easy, even if it feels unnatural at first.

I wonder often if I would feel this way about other languages? When I lived in Egypt in my teens, I picked up Arabic quickly - the words becoming a tapestry of earthy and jewel tones in my (yet known to me) synesthetic mind. It was a difficult language, but one I found easier to “think” in. It’s also a language with stricter rules and boundaries than English - a language greatly impacted and shaped by it’s thrust upon so many cultures via colonization and imperialism, who’s agency and rebellion is found in our odd bits of slang, inflections that feel natural but defy the laws of “grammar.”

To deflect from this path, I have over the last few years really sunk into herbalism. I have late stage lyme, and am so far progressed that pharmaceutical avenues of treatment would be too much for my body to handle - I found an alternative in plant medicine. During my research, I explored a lot of the philosophies and traditions of herbalism - and of plant communication. Many herbalists and plant healers throughout the ages have practiced asking plants for their harvests, communicating through intuitive energetic methods. There are more recent studies which show that plants communicate with us through hormonal chemicals released in the air - tiny suggestions to water or feed or move them. They communicate this way with each other as well - noting when a dangerous insect has arrived, sometimes even luring other friendly insects to come to their aid.

What surprises me most is that through the discovery of epigenetics, we have found that plants will change their genetic structure when influenced by our breath or urine - shifting to become more acute medicine for us. Plants with medicinal properties tend to grow in proportion to the dis-eases they treat - for instance, a map of Kudzu growth (used most commonly to assist with alcoholism and related imbalances) aligns almost perfectly with a map of alcoholism in the United States. As we’ve seen this mass global outbreak of COVID-19, we’ve also seen the most curative and preventative herb, Baikal Scullcap - an ACE2 inhibitor which reduces or even eliminates the pathways of reproduction for the virus, have it’s most fruitful year around the globe. If that’s not an attempt to communicate “hey, I’m here for you. Here is the balance and symbiosis we both need. What ails you feeds me,” I’m not sure what is. Obviously this can be interpreted in many ways, but I also believe firmly that there are an infinite number of ways to communicate - both with and without language - that the epigenetic science behind this also shows us another method of communication.

There is so much more I could say, but I’ll save it for future posts. HERE IS A MEME abt BIRDS xoxoxo

-Fera

#wholesome memes#actual blog#post nature#decolonisation#synesthesia#lymedontkillmyvibe#plantcommunication#animalcommunication

5 notes

·

View notes