Link

0 notes

Link

Berger, J. (2015) About Looking, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. (Downloaded: 27 January 2019).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Project 1: The Instrument

Exercise 1.1: The Instrument

I’m currently feeling that I have missed the point of this exercise. The camera manual reads, “...histograms are intended as a guide only and may differ from those displayed in imaging applications...”

Are learners supposed to take photographs of the backs of their cameras? Using the nearest camera available to hand (my iPhone), I wasn’t able to see any marked differences.

Also, what histogram information does the exercise require; RGB or highlights? The handbook gives a general guide: if the image is dark, tone distribution will be shifted to the left and to the right if the image is bright. Also, what if I am using film?

Exercise 1.2: Point

This image appears to be divided into quarters from the bottom up. I am 5ft 3 inches tall – a taller person’s viewpoint would be different. The camera creates a point towards the top of the frame on the left hand side. The ‘Hilton London Syon Park’ sign points to its mast.

There is more than one visible point to the next image; the ball in the foreground on the left, the patch of blue on the sign on the wall to the right and the yellow bollard in the far middle distance through the gate, which is open.

Here there are three horizontal sections. The front door of the house, situated to the right in the frame, could be seen as a point. The drive also leads to the tree, past the white building in the middle of the photograph.

The green breaks up the similar tones in the paving, driveway, house and sky. There are no shadows.

I have found it difficult to evaluate my images according to these rules. I did not consider the fact that the example images in the course materials are in black and white until writing this learning log. The colours are part of the composition.

Without the narrative around the example image in the course materials, I don’t think I would know what the focal point of it is. The cup draws attention to the space under the chair. What is the thing to the right of the image under the door? Is the corner of the door a point? What is meant by ‘tension’? Emotional?

When taking this photograph I was aware of the reflector on the fence. I had intended to make this a point within the frame, with the fence directing attention to the open gate. Is the tree in the background a point or a distraction?. The position of the camera is not 180 degrees horizontal. It could be argued there is too much empty space to the right. However, it could be seen as two images intentionally spliced together. A join is detectable between the fence and gateway on the left of the frame and the larger grass section, which follows the rule of thirds.

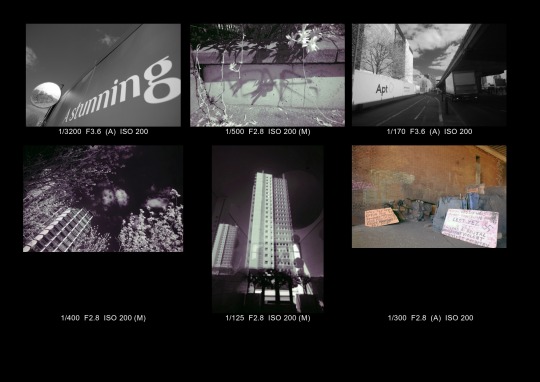

Exercise 1.4: Frame

The camera I used was a full spectrum converted Fuji X-E1 with Fujinon XF 14mm f/2.8 lens and B+W 830 IR filter, testing all for the first time. I used Photoshop to auto-adjust the colour when reviewing the photographs.

I did not use a grid to compose these photographs. When composing ‘A stunning/smile’, I took several photographs because I wanted to include the mirror and various parts of the text. I was not aware of the tree in the background until reviewing the images.

The odd cloud formation was another part of the frame I wanted to include. I placed it centrally; I was aware of the trees and buildings when composing the photograph.

My composite grid differs from the example in the course materials in that I have included a photograph with portrait orientation, and only one colour photograph. I have included the colour image to draw attention to the subject.

0 notes

Text

diane arbus: in the beginning

I don’t know why the gallery has used lower case lettering in its promotional material.

Hayward Gallery, 13 February to 6 May 2019

Organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Curated by Jeff L Rosenheim, Curator in Charge of the Department of Photographs: with Karen Rinaldo, Collections Specialist, Photographs; Martha Deese, Senior Administrator for Exhibitions; and Emily Foss Registrar.

Supported by Cockayne – Grants for the Arts and The London Community Foundation and Alexander Graham, with additional support from Michael G and C Jane Wilson. (Hayward Gallery, 2019).

This exhibition primarily features photographs made with 35mm cameras in and around New York City between 1956 to 1962. Most of the exhibition photographs are gelatin silver prints made by Arbus. Most are held in private collections, and in the Diane Arbus Archive at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

There is also one room displaying A Box of Ten Photographs, a project she worked on between 1969 and 1971. These photographs, on loan from the Victoria and Albert Museum, were printed posthumously by her assistant and student Neil Selkirk (Guggenheim, 2019).

I wondered why nine of these later works are being displayed in a separate room at an exhibition subtitled ‘in the beginning’. Xmas Tree in a living room in Levittown, L.I. 1962 is in the previous room. There is no explanation why. Were they included to show how her work changed over time? They are already kept in London.

There are two rooms of photographs arranged on grids of white columns, “…visitors are free to follow any path they choose as there are only beginnings – no middle and probably no end…” (Hayward Gallery, 2019). I found myself first walking to the back of the room, up and down ‘aisles’ in the opposite direction to other exhibition-goers, to avoid crowding around the prints and to get a better view. Also, what does this statement mean; that her work endures? After visiting the exhibition, I did some reading. I found this quote from a letter she sent to friends in 1957,

“… I am full of a sense of promise, like I often have, the feeling of always being at the beginning…” (Arbus et al, 2012: 141).

I do not know if the organisers of the exhibition are alluding to this remark. I learned that Arbus committed suicide a year after A Box of Ten, a limited portfolio of special prints, with inscribed vellums, was published (Smithsonian, s.d)

Only four sets are known to have been bought in her lifetime, “...by an elite group..” . (Hayward Gallery notice). The notice tells us Marvin Israel designed the packaging, but does not explain who he was. During my reading after the event I learned he was her partner; an artist and, from 1961, art director of Harper’s Bazaar which published her work during the period the Hayward exhibition mainly focusses on.

Between 1956 and 1962 Arbus stopped using a medium format Rolleiflex in favour of a 35mm Nikon (Arbus et al, 2012: 139). Unlike bulky 2 ¼ cameras which “…require the subject’s cooperation and participation…” (Arbus et al, 2012: 59), 35 mm SLRs allow photographers to capture moments and quickly disconnect from the subject.

Images such as:

Old Woman in hospital bed, NYC 1958

Lady in the shower, Coney Island, N.Y. 1959

Man in hat, trunks, sock and shoes, Coney Island 1960

Two girls by a brick wall, NYC 1961

raise the question in my mind about whether these people gave their consent to be photographed, or if some were staged.

In a letter to Marvin Israel she confessed that when visiting the shrine of a disinterred saint , she,

“…got a terrible impulse to photograph her and I tremulously did which wasn’t legal so I pretended to be praying and pregnant…” (Arbus et al, 2012: 146)

In a postcard she sent to Marvin Israel in 1960 she wrote,

“…This photographing is really the business of stealing… I feel indebted to everything for having taken it or being about to…” (Arbus et al, 2012: 147)

I took some notes during my tour of the exhibition of images I found noteworthy. This image Mother Cabrini, a disinterred saint in her glass and gold casket, N.Y.C. 1960 was not among them. I found the story behind the image more interesting. Knowing the photograph is a furtive snap changes its meaning; the exhibition does not explain much. I don’t remember if there was an audio guide. How many people were there like me wa/ondering around the grid?

I did not buy the catalogue, priced at £35, but noted that Revelations was priced at £75. I thought the price was quite high. However, I thought the reproductions were of a better quality and saw that one of the editors was her daughter. I assumed Doon Arbus would be able to share more information about her mother than any other writer. I bought a cheaper copy online.

On reading Revelations I found out that, up until 1958, Arbus experimented with cropping. Photographers and art editors at the time used this technique retrospectively to reveal an image within an image. It could,

“…impose a sense of immediacy, or of a privileged, almost private view after the fact…” (Arbus et al, 2012:52)

Boy above a crowd NYC 1957 illustrates this idea but I do not know whether Arbus cropped it, not having seen the contact sheets. The title does not indicate to the audience what the audience depicted are looking at. They are looking to the left, the boy Arbus wants us to focus on is looking directly at us.

In 1956 Arbus ended her photographic partnership with her husband. She felt her role in their commercial business was as “a glorified stylist” (Arbus et al, 2012: 139). She joined two photography courses taught by Lisette Model (1956 and 57). In the 1940s, Model photographed ordinary people in the streets of New York City.

In 1971 Arbus told students in a master class,

“…In the beginning… I used to make very grainy things. I’d be fascinated by what the grain did because it would make a tapestry of all these little dots…Skin would be the same as water would be the same as sky and you would be dealing mostly in dark and light not so much in flesh and blood… It was my teacher…who finally made it clear to me that the more specific you are, the more general it’ll be…”

(Arbus et al, 2012: 141)

I do not remember seeing Coney Island 1960 (Windy Group) in the exhibition. It is in Revelations, but I am unable to locate the image online. It shows a group of people on a windy beach; a woman is bending over away from the camera and her stripy dress is blowing in the wind. It is extremely grainy; did Arbus intend the grain to suggest a sand storm?

Towards the end of her life Arbus told her students,

“…I remember a long time ago when I first began to photograph I thought, There are an awful lot of people in the world and it’s going to be terribly hard to photograph all of them, so if I photograph some kind of generalized human being, everybody will recognize it…And there are certain evasions, certain nicenesses that I think you have to get out of..” (Arbus et al, 1992:10)

At the Hayward exhibition, I noticed that,

Kid in black face NYC, 1957 is exhibited near, Lady on a bus NYC, 1957.

Was the year-long (1955-6) Montgomery Bus Boycott in Arbus’s mind? Around this time Arbus was trying to find photographic editorial work and took some photographs of litter for a magazine, for which she was unpaid.

“…I followed flying newspapers…running like mad to keep up with dick tracy…” (Arbus et al, 2012: 142)

Windblown headline on a dark pavement, NYC 1956. Most of the photographs in this exhibition are of people. I did not understand the appeal of some of the photographs lacking them, such as those of “…psuedo places…” (Arbus et al, 2012: 163) for example, A castle in Disneyland, cal., 1962, or Rocks on heels, Disneyland, Cal., 1963, but I thought this particular print was inspiring.

I noted a number of photographs taken inside and outside cinemas. Several are of the screen, taken at some distance from it, from the audience’s viewpoint;

A Dominant Picture 1958

Man on screen being choked 1958

had a personal resonance. There is also a close up, probably taken in a cinema, of a scene from the controversial film Baby Doll, 1956.

In Movie theater usher standing by the box office NYC, 1956 an usher stands by the box office in an oversized uniform. It occurred to me, after seeing an online reproduction of this photograph away from the exhibition, that it is reminiscent of a Soviet style uniform. Was Arbus intending to remind us of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising?

In 42nd Street Movie Theater Audience NYC 1958 Arbus’s camera is placed some distance away from the scene. A projector beam cuts through the fug of cigarette smoke. It is not easy to tell what people are doing; there is some blurring, perhaps there are people asleep and a couple kissing. A print made by Neil Selkirk, her student and assistant, is valued at between $20,000 - 30,000. I quite liked the photograph at the exhibition, but I do not think it is that extraordinary.

It seemed to me that Arbus’s intention was to make the ordinary extraordinary and the extraordinary ordinary. In The Backwards Man in his hotel room, 1961 a man is standing in a standard hotel room. His head is directed to the left of the frame, his feet to the right. He is wearing a full length clear plastic mac indoors. Is this to draw attention to his body? After the exhibition I learned he was a contortionist from Hubert’s Dime Museum and Flea Circus in Times Square called Joe Allen;

“… Joe Allen is a metaphor for human destiny – walking blind into the future with an eye on the past…” note in her appointment book (Arbus, 2012:154)

Sontag offered a suggestion as to why Arbus chose her subjects.

“…At the beginning of the sixties, the thriving Freak Show at Coney Island was outlawed; the pressure is on to raze the Times Square turf of drag queens and hustlers and cover it with skyscrapers. And the inhabitants of deviant underworlds are evicted from their restricted territories – banned as unseemly, a public nuisance, obscene, of just unprofitable…”

(Sontag, 1973. 43-44)

There are many photographs of female drag artists in the show. Two different interpretations of ‘woman’ can be seen in the fleshy beauty of Girl in her circus costume backstage, Palisades Park, N.J. 1960, and the haughty and fabulous Blonde female impersonator standing by a dressing table, Hempstead L.I 1959, a coded appropriation of ‘womanliness’.

In October 1959 Arbus started work on a project about aspects of New York life for Esquire magazine, photographing “…the posh to the sordid…” (typewritten letter to Robert Benton, art director of Esquire (Revelations, 2012: 333)

I made a note of the title, Woman in white fur with cigarette, Mulberry Street NYC 1958, at the time of visiting the exhibition, but did not really reflect on the photograph. I felt pressurised by the crowd to move on. The unnamed woman’s stance could be interpreted as expressing her annoyance at being photographed, self-confidence, or self-entitlement. Is she scowling? She fills the frame, and appears quite large. The lights in the background, possibly Xmas street lights, appear to surround her head. Are we meant to see a Valkyrie? The location is Mulberry Street, NYC; the street name made me think of expensive handbags. Is the woman in the background, who I have only just noticed, smiling obsequiously or simply smiling?

For me, Arbus’s titles often suggest a deadpan or sardonic humour, which I enjoy. This title, Miss Maria Seymour dancing with Baron Theo Von Roth at the Grand Opera Ball, NYC 1959, is similar to captions of photographs in society magazines. I don’t know now why I thought this was funny; I did not make adequate notes at the exhibition because I thought I would be able to access the image online at home afterwards.

For some of this work she obtained a Police pass (Revelations, 2012:144); Corpse with receding hairline and a toe tag, N.Y.C. 1959

Looking at photographs of Israel after the exhibition, (Revelations, 2012:145), could this photograph be an inside joke? A notice on the wall at entrance of the Hayward states,

“…This exhibition contains images that some visitors may find upsetting and some that contain nudity. If you require further information, please speak to an exhibition host…”

In postcards sent to Marvin Israel in January 1960 she wrote about a disturbing scene she had photographed,

“… I am not ghoulish am I? I absolutely hate to have a bad conscience, I think it is lewd…Is everyone ghoulish? It wouldn’t anyway have been better to turn away, would it…?” (Revelations, 2012: 145-6).

All layers of society are portrayed in the exhibition. Among the photographs of society people are photographs of performers at the Hubert’s Dime Museum and Flea Circus in Times Square, such as Hezekiah Trambles, ‘The Jungle Creep’. The close up of ‘The Jungle Creep’ is a powerful image. He played a ‘Wild Man of Borneo’ racist stereotype for a living. Tramble’s face fills the frame; the photograph is blurred and grainy. A light source catches highlights in his eyes, perhaps a button over his Adams apple, and a tooth. How many teeth does he have? Are their tears in his upwardly directed eyes? His eyes appear unfocussed. He is photographed from below; he looks monumental.

Arbus photographed various people who she described as ‘freaks’, ‘The Sensitives’ and ‘singular people’. In 1971 she told her students,

“…Freaks was a thing I photographed a lot… There’s a quality of legend about freaks…Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats…” (Arbus et al, 1992:3).

By making us look up at Trambles’ face, did Arbus intend us to see someone deranged? Or a Man with human dignity?

In a notebook she wrote,

“..If we are all freaks the task is to become as much as possible the freak we are...” (Revelations, 2012: 54) and in a postcard to Marvin Israel in 1960 she wrote,

“..Freaks are a fairy tale for grownups. A metaphor which bleeds…” (Revelations, 2012: 54)

In 1961 Arbus completed a story, “The Full Circle” which included portraits of six people including Stormé de Larverie from the Jewel Box Revue’s touring drag artist show, ‘Twenty-Five Men and a Girl’, Miss Stormé de Larverie, the Lady who appears to be a Gentleman NYC 1961.

Neither Esquire nor Harper’s Bazaar published the story with de Larverie. Esquire wanted to leave out Stormé “…due to lack of space. Infinity, the publication of the American Society of Magazine Photographers published the story in 1962 which included de Larverie. Was the de Larverie photograph initially excluded because it depicted a lesbian, or because editors regarded the print as being unremarkable? The Hayward gallery offers no information about de Larverie’s historical importance.

I wasn’t sure if the exhibition was presenting Arbus as a feminist;

Barbershop interior through a glass door, NYC 1957

Blurry woman gazing up smiling, NYC 1957-8

Mood meter machine, NYC 1957

In the barbershop interior we can see men looking at a woman taking photographs in the street at night. Their various expressions include puzzlement, amusement and incredulity. The presence of the woman photographer is only suggested by her reflection in the glass. I am that woman now looking from the outside in. Am I obliged to become involved with what I photograph?

Of the Box of Ten photographs, one of my favourites is,

Retired man and his wife at home in a nudist camp one morning NJ 1963

I see this as a cosy and affectionate. Soft sunlight filters through the net curtains; it is a domestic scene with a twist.

Arbus described her experience of taking photographs in nudist camps in 1971, where she was required to take photographs naked,

“…You may think you’re not (a nudist) but you are…” (Arbus et al, 1992: 4-5)

As a suburban, semi-educated, left-leaning liberal standing in a contemporary Western art gallery, the wall notice warning about nudity surprised me a bit; I wasn’t concerned by the nudity displayed within this context.

Neil Selkirk, who printed the Box of Ten, believed Arbus’s prints look different from other photographers’. She did no dodging or burning,

“…If she ever had the urge or the knowledge to make the print beautiful in a conventional sense, she resisted it. The unique quality of Diane’s prints seems a direct response to what is required if one is extremely curious and utterly dispassionate...” (Revelations, 2012: 275)

He thought she had intended to make the final image look like snapshots or newspaper photographs. To me, the 35 mm photographs in the exhibition generally look like snapshots; the Box of Ten artworks look like beautiful parodies of photographs specific to glossy magazine features. Arbus’ photographs could be seen as diverting, rather like a day out at an art gallery

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arbus, D (edited by Arbus, Doon, Israel, M) (1992) Diane Arbus, London, Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd.

Arbus, Diane, Arbus Doon, Phillips; S, Sussmann E, Selkirk N, J L Rosenheim (2012) Revelations: Diane Arbus, Munich, Schirmer/Mosel

Guggenheim, K (2019) Diane Arbus: An interview with Jeff L. Rosenheim and Karan Rinaldo. At: https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/blog/diane-arbus-interview-jeff-rosenheim-karan-rinaldo-hayward-gallery (Accessed on 24 March 2019)

Hayward Gallery (2019) Hayward Gallery Exhibition Guide, London, Hayward Gallery

Metropolitan Museum of Art (2019) diane arbus in the beginning [online] At https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2016/diane-arbus (Accessed on 30 March 2019)

Smithsonian American Art Museum (s.d) A box of ten photographs [online press release] At: https://s3.amazonaws.com/assets.saam.media/files/documents/2018-04/wall%20text.pdf (Accessed on 30 March 2019).

Sontag S (1973) ‘America seen through photographs, darkly’ in On Photography (1979) London, Penguin Books Ltd

0 notes

Text

Notes on BBC 4 documentary, ‘Don McCullin: Looking for England’

Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0002dv0 until 5 March 2019. (Accessed 18 February 2019)

At the start of the documentary, McCullin comments that he hates being called a war photographer; he is happy to be called a photographer. This documentary follows him as he photographs people in various locations around the country. At 83, McCullin still feels he has to find new work and experiences. “…There isn’t a nation where the class system is so public...”

He feels that tragic events in his childhood home helped him understand emotion. In the documentary he returns to subjects and locations he has previously photographed, “...reincarnating...” photographs from 50 years ago. We hear the voices of people who are street homeless in London. Questions are initiated by McCullin, except for one; “Are you a policeman?” As the only narrator, McCullin’s voice dominates the programme.

I noted how McCullin walks the streets of London, followed by a camera crew, with an expensive mid format film camera slung over his shoulder in full view of passers-by – I carry my camera around in a shopping bag. McCullin comments that his camera is very heavy, uncomfortable and hurts his hands. Yet the camera drives him on and on, giving him “…an extension…”. He believes digital does not transform the atmosphere of a photograph; that certain subjects need film. He does not, however, go into further details about this in this documentary. He believes film is ten times harder than digital.

McCullin spends 4-5 days in the darkroom each week. We see an assistant in the documentary, but he is not interviewed. McCullin prints as dark as possible, (he described an image he was printing as “...nice and contrasty…”), but says he does not know why. He says he has used photography to find himself in the world, and it has given him a lifetime’s experience. McCullin says when he is in the darkroom, he is at peace with himself; he is in a tomb he understands.

At a hunt, McCullin comments that Britain is more divided now than it has ever been. He revisits Bradford, “..the most interesting city in England…” and a good example of the North/South divide. A sense of injustice still exists, where people feel that any local profit goes to London. He says that his 70s Bradford photographs were not commissioned. He remarks that Bradford now has lots of shabbiness and improvement. I found it interesting that, back in the 1970s, people in Consett, Co Durham, complained about the way the Sunday Times and McCullin depicted them; I found some of the Bradford photographs in the exhibition to be potentially insulting.

0 notes

Text

McCullin at Tate Britain - 5 February 2019

My initial feelings today were that I did not feel like travelling to Vauxhall to spend a relatively large amount of money. I also felt unease about consuming images of atrocities as a leisure activity; a security guard cheerily said to me as I approached the rooms, ‘Enjoy the exhibition’.

Compared to other exhibitions I have attended at the Tate, visitors do get to see a lot for the entrance fee. There are ten rooms in this retrospective exhibition, which spans sixty years of Don McCullin’s career as a photographer.

When I found out that the exhibition was at Tate Britain, I wondered why the work of a photo-journalist is being shown in an art gallery. I noticed from the start that there was no information accompanying the prints about how they were made, just titles and dates. Only at the end of the exhibition was there a small sign displayed on the wall, easily overlooked, which read,

“All photographs are gelatin silver print, printed by Don McCullin”.

The caption entitled ‘Printing’ describes how McCullin repeatedly returns to his negatives, in an attempt to “..produce the perfect print. In doing so he hopes to do justice to the perpetually harrowing content of his images..”

A caption on the wall entitled ‘Photojournalism and Art’ states,

“…McCullin has always avoided the term ‘art’ when discussing his work. Yet through careful, intuitive composition and framing he creates images that have a formal clarity and even an uncomfortable kind of beauty…”

The caption describes, throughout the history of photojournalism as a genre, the ethical dilemma involved when tragedy is made to appear beautiful;

“..But McCullin hopes that his skilful composition helps these images stick in people’s minds. He attempts to make it impossible for us to ignore the atrocities taking place in the world….”

Another caption, ‘Photojournalism in the gallery’ states McCullin’s belief that, “..as newspapers won’t publish these images, they must have a life beyond my archive..”

Considering some controversies regarding sponsorship of major exhibitions, for example BP, I also wondered who is sponsoring this one: Tim Jeffries, ‘heir to the Green Shield Stamp fortune’, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/relationships/10465550/Tim-Jefferies-Im-not-a-playboy.html (accessed 9 February 2019) and owner of Hamiltons Gallery in Mayfair; The Mead Family Foundation, a US organisation describing itself as ‘philanthropic’ https://meadfamilyfdn.org/about-us/foundation-history/ (Accessed 9 February 2019) and Tate Patrons - individuals and corporations.

One quote from McCullin I noted on the wall is, “..it’s not a case of, ‘There but for the grace of God go I’; it’s a case of, ‘I’ve been there..’ McCullin grew up in Finsbury Park, in a poor neighbourhood. He left school at 15 with no qualifications (http://www.johnjones.co.uk/news/2015/09/don-mccullin-eighty-at-hamiltons-9-september-3-october-2015/ Accessed 9 February 2019). His National Service was as a photographic assistant with the RAF, and he was posted in Egypt, Kenya and Cyprus. On returning to London he took photographs of his friends, members of The Guv’nors gang. There is one from 1958 of The Guv’nors in their Sunday Suits,

https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_1000,h_800,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy/ws-hamiltons/usr/images/artworks/main_image/items/9a/9a43d6f4fad744e8b958532af7226da1/don-mccullin_the-guvnors-in-their-sunday-suits-finsbury-park-london-1958.jpg (Accessed 5 February 2019)

These young men appear neither “...second-rate, clumsy, uncouth..” nor “..defensive..” in their suits (Berger, J 2015, About Looking, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [27 January 2019]) but at ease with themselves and the camera. If they had been standing around a conference table, all bar one could have been mistaken for members of the professional ruling class.

McCullin showed these photos to the picture editor of the Observer, and earned his first commission. https://donmccullin.com/don-mccullin/ (Accessed 5 February 2019).

Two photographs from the early 1960s depicting London street scenes, ‘Sheep going to the slaughterhouse early morning near the Caledonian Road 1965’, https://www.artsy.net/artwork/don-mccullin-sheep-going-to-the-slaughter-early-morning-near-the-caledonian-road-london#! (Accessed 5 February 2019)and ‘Horses delivering beer Cable Street 1962’ are, I think, romantic, soft focus , painterly portrayals of everyday events, and there is tenderness in ‘Hessel Street, 1962’, https://static.standard.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2019/02/04/09/Hessel-Street-Jewish-District-East-End-London-1962.jpg?width=1368&height=912&fit=bounds&format=pjpg&auto=webp&quality=70 (Accessed 5 February 2019)

Some of the northern England photos made me think, ‘It’s grainy oop north’, and I asked myself, do grainy photographs equal ‘realism’? Did McCullin set a standard visual language? The caption under ‘Volubilis, Morocco 2007’ states,

“…People say my landscapes look like war scenes because I do print them very dark. But… I suppose the darkness is in me, really…”

In 1964 he was commissioned by the Observer to cover the war in Cyprus. In the commentary, McCullin describes this time as the,

“…beginnings of self-knowledge…empathy. Able to share other people’s emotional experiences, live with them silently, transmit them…”

In ‘Murder in a Turkish Village’, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/mccullin-murder-in-a-turkish-village-ar01186 (Accessed 5 February 2019), a young woman lies over the body of a man, and looks directly at the camera. The image looks posed; the position of her body and direct gaze is self-conscious and deliberate. There is a comment from McCullin later under ‘A young dead North Vietnamese soldier with his possessions 1968’, ‘..I only ever played with the truth once…” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/mccullin-a-young-dead-north-vietnamese-soldier-with-his-possessions-ar01195 (Accessed 9 February 2019). He describes this image as “..the only contrived picture I’ve taken in a war..”. McCullin was disgusted by some of the US soldiers he was following taking souvenirs from the soldier’s dead body. McCullin rearranged the dead soldier’s belongings around him and took the photograph.

A number of titles of the photographs in this exhibition use the words ‘murder of’, which are more emotive than the more neutral ‘death of’. A quote from McCullin on the wall at the Biafra section states,

“..it was beyond war, it was beyond journalism, it was beyond photography, but not beyond politics…"

However, at the Northern Ireland section, in comments on the wall entitled ‘Neutrality’, McCullin describes himself as a “..totally neutral passing-through person…” Reading the captions on his Northern Ireland photographs, contrasting people going about their everyday lives surrounded by abnormal events and circumstances, as in:

https://d2jv9003bew7ag.cloudfront.net/uploads/Don-McCullin-Londonderry.jpg

(Accessed 9 February), I felt this statement to be disingenuous; they tell the viewer that they were taken in, ‘Londonderry’. But McCullin also describes British troops’ hostility towards him when a soldier was shot and accusations that he was helping the rioters and ultimately”… the terrorists…”.

The title of this photograph is ‘Local Boys in Bradford, 1972’, https://d2jv9003bew7ag.cloudfront.net/uploads/Don-McCullin-Local-Boys-in-Bradford.jpg (Accessed 9 February 2019)

In the course of his work, McCullin put himself at personal risk. In the Congo he disguised himself as a mercenary working for the government. We see torturers posing for the camera. “..I was trying to photograph in a way Goya painted or did his war sketches…I found it hard not to burst into tears…” One woman near me did just this; my eyes welled up when I read the caption to Albino Boy, 1968, https://static.independent.co.uk/s3fs-public/thumbnails/image/2012/12/29/19/16-ontheedge1.jpg?width=1368&height=912&fit=bounds&format=pjpg&auto=webp&quality=70 (Accessed 9 February 2019) holding an “…empty corned beef tin..”

I noted small details and gestures in several of his images; a sheep going to slaughter turning in the opposite direction, a blonde child on a truck full of Kurdish refugees in ‘Fleeing Kurds from Saddam Hussein's aerial attacks, 1991’. The pathetically small placard held by a protestor facing a phalanx of police officers, ‘Protester, Cuban Missile Crisis, Whitehall, London, 1962’, https://www.artsy.net/artwork/don-mccullin-protester-cuban-missile-crisis-whitehall-london#! (Accessed 9 February 2019), is comparable to a young man wielding a stick against armed British soldiers in ‘The Bogside, 1971’ https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/mccullin-northern-ireland-the-bogside-londonderry-ar01189 (Accessed 9 February 2019)

The commentary states that McCullin was “..deeply affected by the trauma of reporting some of the most violent conflicts..” The Sunday Times Magazine, the first colour supplement to be published in the UK. (‘Projection Room commentary) commissioned the Biafra photographs. In December 1969 the British Government supported the Nigeria federal forces fighting Biafra and, as Berger pointed out, the Sunday Times “…politically supported the policies responsible for the violence…” Berger, J 2015, About Looking, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. [Accessed 27 January 2019]. McCullin worked for the Sunday Times for eighteen years.

In 1968 he spent 11 days with US troops fighting in Vietnam. The exhibition displays some of McCullin’s possesions he had with him in Vietnam,.Biafra and Cambodia. Alongside his Nikon F with a bullet hole in it, is his passport stamped with a 1969 Vietnamese tourist visa, as if he were on holiday. At this point in the exhibition, I wondered whether McCullin’s sense of empathy for his subjects was losing focus. The wall in the Cambodia, 1970 section displayed this quote from him,

“It could have so easily been my dead corpse rattling. I thought, he’s gone instead of me…”

In the early 1970s, McCullin took photographs in the East End of London, in particular portraits of homeless people.

“..There are social wars that are worthwhile. I don’t want to encourage people to think photography is only necessary through the tragedy of war…”

A thought came into my mind; how did McCullin, world famous photographer, approach these people? In ‘Homeless drunk man on Brick Lane 1971’, a woman breezes past, apparently oblivious to this man. I wondered who this woman was. Did she consent to be displayed in this photograph, perhaps be seen in a negative light? Some of the people photographed in Bangladesh appear to have angry expressions on their faces; where are these people now? The child looking directly at the camera in ‘The Murder of a Turkish Shepherd, Cyprus Civil War, 1964’, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/mccullin-the-murder-of-a-turkish-shepherd-cyprus-civil-war-ar01183 (Accessed 9 February 2019) looks, perhaps, accusingly at the photographer. McCullin comments,

“I feel guilty about the people I photograph. It’s true, I do. Why should I be celebrated at the cost of other people’s suffering and lives. I don’t sit comfortably with laurels on my head” (Caption under the photograph ‘A boy at the funeral of his father who died of AIDS, Kawama Cemetery, Ndola, Zambia 2000)

I thought some of the people in the British Summertime, Bradford and India photographs appeared grotesque. McCullin uses the word, “..eccentric…”, but some of the images, such as ‘Bradford City Centre, 1970’, made me wonder if we are “..laughing at ourselves..” or whether McCullin was laughing at other people?

Some of the Bradford photographs, however, do present the viewer with extreme poverty of a British kind, and I felt there was tenderness in the photograph of a couple with a child and a pile of clothes. We are not told much about these people; only Jean, a homeless woman in London, has a name.

“…I want to create a voice for the people in those pictures. I want the voice to seduce people into actually hanging on a bit longer…so that they go away not with an intimidating memory but with a conscious obligation...’

My thought was, if it is McCullin who creates a voice, whose voice is it? How can this obligation be fulfilled? Do people passing through this exhibition do anything more than look?

‘Bradford, 1970’, shows a stripper in a pub bending over; we cannot see her face. The focus is on the leers and, perhaps, bemusement, of the male onlookers. A solitary woman in the foreground looks as if she is looking beyond the stripper. It occurred to me that a lot of what I was seeing, images designed to stimulate and seduce, published in the glossy lifestyle and entertainment Sunday supplements and £25 catalogues for the purpose of making money, made remote from the actuality of the lives of the people depicted, could be regarded by some as ‘the horrors of war porn’. Some of the related events advertised on the Tate website include, wine tasting and dinner; https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/don-mccullin/wine-tasting-dinner-don-mccullin. (Accessed 9 February 2019). I wonder whether corned beef will be on the menu?

0 notes

Link

Berger, J. (2015) About Looking, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. (Downloaded: 27 January 2019).

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reflections on the SQ3R Reading Task

The texts I chose were from Berger, J. (2015) About Looking, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central. (Downloaded: 27 January 2019). When looking at the listing in the online library catalogue, I thought the book had been written fairly recently. In fact, these essays date from the 1970s.

The first essay I read, ‘Why look at animals?’, is dated 1977. I chose to read this because I thought it may offer some answers to the question why I decided to post some photographs of deer on Facebook, and why some people liked them.

The second chapter, ‘Uses of photography’ is a collection of short essays Berger wrote in the 1970s. A pdf copy I have annotated can be downloaded from the Dropbox link above.

I found the second chapter to be more potentially helpful to my studies than the first. The problem with this task, however, is that this is no specific brief, no essay title or questions to answer. I felt I was reading the first chapter in isolation from the book’s context. A main stage of SQ3R is to formulate questions about the content of a text. My reading was unfocussed, and I was not sure what questions to ask since I did not have a specific question to answer.

With the first text, I became preoccupied with answering the question ‘how’, rather than ‘why’, and fascinated with details. I began to feel I lacked the skills/ability to take an overarching, global view of the text. I found myself arguing with the text; ideas were springing up but, again, they were unfocussed.

Generally, this task took far longer than I had initially thought it would or should. When I have studied before, I tended to highlight relevant passages from a number of texts, perhaps in Adobe reader or with post-its, then reworded and combined writers’ ideas with mine. I have never paraphrased entire chapters from books.

Nevertheless, this exercise has sparked some ideas for further reading, time allowing.

1 note

·

View note