Text

American Afterlife

David Leo Rice On Steve Erickson’s Shadowbahn

Simultaneous Histories

Shadowbahn, Steve Erickson’s 10th novel, opens with the impossible happening in America: the Twin Towers appear in the heart of the Badlands in South Dakota and Jesse Presley, Elvis’s stillborn twin, wakes up on the 93rd floor of the southern one. Much of the “United States of Disunion,” as the nation is known here, flocks in to bear witness, only to fall into intense disagreement about what has happened and what it means.

Long obsessed with the the fault lines running through the American soul, Erickson has now given us the first key novel of the Trump Era. Written before the election but published after, Shadowbahn is hyper-aware of the ways in which America has not only been split into rival factions, but into mutually exclusive realities. If the old wisdom was that “it’s impossible to be in two places at once,” in 2017 it has become impossible to be in one place at once. All places in Trump’s America, which represents both the End Times and the supposed return of a great mythic past, are frighteningly multiple.

After an opening scene in which a trucker whose truck bears the bumper sticker “SAVE AMERICA FROM ITSELF” discovers the “American Stonehenge” in the Badlands, Shadowbahn only gets stranger as it goes along. Jesse Presley works up the nerve to jump out of the South Tower and finds himself flying into a revised 20th century where JFK lost the Democratic nomination to Adlai Stevenson and the Beatles never took off. Making his way as a cantankerous music critic, Presley meets Andy Warhol and falls into a bizarro version of the Factory scene, commenting on the decline of America from within the novel just as Erickson comments from without. Meanwhile, a brother and sister (one born in California, the other in Ethiopia) drive across near-future America via a series of lost highways and secret tunnels, discussing their fraught relationship with their writer father (a clear Erickson stand-in, carried over from 2012’s These Dreams of You) en route to visit their mother in Michigan. By the time they reach the Badlands and see the Towers for themselves, numerous realities have been born and died and reemerged transfigured, and the map has gotten ever more skewed without quite ceasing to be navigable.

In bringing all these strands together without forcing them to cohere, Shadowbahn marks a culmination of both Erickson’s apocalypticism and his vision of history as a porous entity, full of glitches, wormholes, and “Rupture zones.” Straddling the Millennium, the terms of his ongoing project are most clearly defined by 1989’s Tours of the Black Clock, which charts a simultaneous history in which Hitler far outlives the 1940s, eventually coming to America. That novel—which lent its name to the glorious and now sadly defunct literary journal Black Clock, yet another casualty of 2016—develops the notion of hidden events running parallel to, and occasionally intersecting with, those we’re aware of. The black clock itself is the embodiment of this idea: it’s the “dark back of time” (to borrow a phrase from Javier Marías), ticking with unseen minutes and hours behind those we perceive passing.

Like the black clock, the shadowbahn renders subjective experience objective, making Erickson’s psychic landscape disturbingly physical. Cutting “through the heart of the country from one end to the other with impunity,” it connects disparate times and places the way a jittery radio dial splices together stations.

On the one hand, it’s a dangerous strand of wishful thinking to imagine a simultaneous America in which Donald Trump is not our president, or one in which he turns out to be merely a blowhard and not a tyrant; on the other hand, the election represents a possibly unfixable rift in the fabric of our national consciousness, so that the present we now occupy is both unimaginable and hyperreal—so in-your-face it’s impossible to see.

Not Quite a Surrealist

By charting this process, Erickson’s work bears resemblance to that of sci-fi visionaries like Philip K. Dick, J. G. Ballard, and William Gibson, but he differs from them in that he has a poet’s soul, not a paranoiac’s. Though he makes use of the language and imagery of sci-fi, his simultaneous histories excavate buried layers of how our reality actually is, not alternate paths it could have taken or could one day take.

This is not to say that Erickson’s work isn’t heady, just that its primary theme is heartbreak, not cracks in the matrix. He believes too strongly in the promise of what America could be to give in fully to highbrow cynicism. In this sense, he’s a patriotic writer, one committed to an American promise that’s been broken over and over again without yet ceasing to resonate.

Just as Erickson isn’t exactly a sci-fi writer, he’s not quite a surrealist either. Perhaps in the European surrealism of the early 20th century—Buñuel, Dalí, Magritte—there was a sense that the external world had become too real, and thus that departing from it (or rising above it, in the literal sense of the term sur-real) was a necessary and plausible response. But now, almost a century after Un Chien Andalou, the events around us and their incessant representation online are too bizarre and too ubiquitous to satirize or depart from: everything, in one way or another, is part of the same post-truth morass. If this is the logic that 21st century fascism will exploit, then Erickson’s determination to plunge all the way into the real, deeper than is comfortable, rather than departing from it or offering any reassuring vision of its ultimate unity, has never been more necessary.

Disjunctive Style

Shadowbahn is self-consciously a symptom of the situation it reflects: the style itself (composed of lists, snippets of dialogue, newspaper clippings, and free-floating paragraphs) is as disjointed and hard to navigate as the lost roads its characters drive down. In this regard, Erickson’s authorial logic has a strange resonance with Trump’s: the shared understanding that our American language is one of constant revision and self-contradiction, and that the grotesque distance between the American Dream and its reality only makes that Dream grow stronger. Needless to say, this language holds great potential for both good and evil.

Living in the End Times

Jesse Presley dates America’s lifespan as running from 1776 to 2001, and yet he still exists in America; indeed he exists for the first time long twenty years after the Towers fell. This means that he’s living in an afterlife, along with everyone else in the novel.

Whether one chooses 2001 or 2016 as the year of America’s death, there’s no denying that we’re all sharing that afterlife now. The apocalypse may have come, but here we still are. In this sense, the book's value lies in its exploration of the Times aspect of the End Times. The End, if and when it truly comes, will neither require nor allow for literature (”when you're dead, you're dead,” as they say), but the Times do require interpretation and consideration, more so than ever because their rules are unwritten.

Since life goes on, growing stranger but not yet unlivable, a book like Shadowbahn serves as a bulwark against numbness and the dangerous belief that the only response to incomprehensibility is inaction. Much to the contrary, Erickson argues that even when reality has splintered, it still contains right and wrong and the two remain distinguishable, in art and in life, until enough people stop believing they are.

American Music

Animating these End Times, as in much of Erickson’s work, music is the one source of renewal. Perhaps because it’s an ephemeral, ever-evolving entity, deriving its power from groove and rhythm, not from rhetoric and ideology, music, especially the blues, which was born out of oppression and worked to overcome it, is the one sanctum in which the American Dream can’t be killed. Music streams from the Towers “like the northern lights”—a natural phenomenon that verges on the supernatural—and everyone who flocks to the Badlands hears different songs, from a sheriff nostalgic for the tunes of her youth to an older man hearing Brian Eno for the first time. This too echoes the current multiplicity of news and social media feeds we all curate, plugging into whichever version of reality we find most satisfying or most exciting, and yet, beneath this disjunct, the power of music itself remains singular.

Late in the novel Erickson writes, “At the previous century’s root was a blues sung at the moment when America defiled its own great idea, which was the moment that idea was born.” Throughout Presley’s and the siblings’ long strange trips, blues, rockabilly, and spirituals like “Shenandoah” (which recurs numerous times throughout the book, sometimes with the word “Shadowbahn” set to the same tune) express both yearning for what America could be and outrage at what it’s become.

Further, with many of the novel’s sections organized as annotations to playlists of classic and forgotten songs, and an absent father (the “Supreme Sequencer ensconced on a mountaintop”) communicating with his children through his mp3 collection, Shadowbahn posits music as our only means of straining to hear the voice of God in the new American desert. Maybe, in one simultaneous history, the current moment will revert us not to some whitewashed version of the 1950s, but all the way back to an age of primal wandering among weird monoliths and along unmarked highways, praying for salvation wherever it may be found. And perhaps out of this, a new America, however disfigured and unruly, will begin to grow, one in which we listen not to the punishing voices of the Old Testament patriarchs but to that of Elvis and the blues and whatever musical forms are still to come.

A Future

The possibility of such a regeneration is the only hope Shadowbahn leaves us with. This is a hope for American life going on, and also a hope for Erickson’s continued literary project, which has by now fully processed the psychic fallout of the 20th century and begun in earnest on the 21st, a time when it seems that “wealth and power is the only American idea left.”

Until now, all of Erickson’s novels have been self-referential, a giant interconnected body of work developing alongside the history we all share, deviating from it but always returning to some recognizable baseline of communal fact. Now that history is unraveling, splitting into ever narrower and less internally consistent versions, perhaps a similar unraveling will occur in Erickson’s future work. There’s certainly no American author better suited to embrace the assault on reality we’re now witnessing, and the ways in which history has been jump-started again, after the lull of the Obama years. No longer are we listening to an album we all know; the soundtrack of 2017 is a stranger’s mp3 player set on Shuffle. Given that there’s no longer any stable ground to stand on, the job of serious contemporary fiction is to reflect this instability, not to deny it.

At the very end of the novel, the truck with the “SAVE AMERICA FROM ITSELF” bumper sticker reappears, this time in a ditch beside the highway, its driver having fallen asleep at the wheel. The siblings, after some debate, decide to rescue him. In beginning to consider how such an act of rescue might still be possible on the national scale, one could do far worse than consulting Shadowbahn for inspiration.

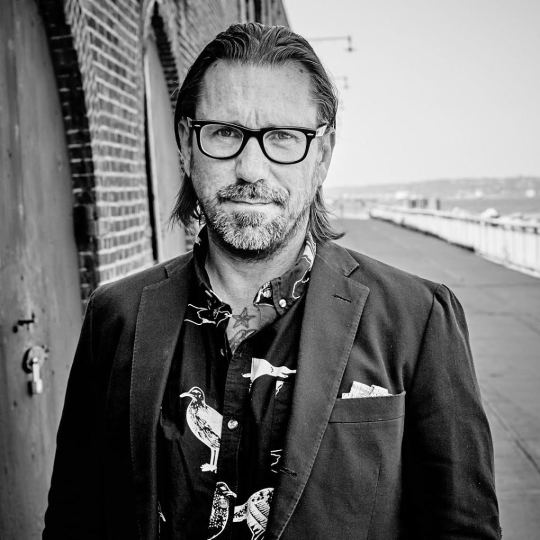

David Leo Rice is a writer and animator living in NYC. His stories have appeared in Black Clock, The Collagist, Birkensnake, The Rumpus, Hobart, Volume 1 Brooklyn, and elsewhere. He's online at www.raviddice.com, and his first novel, A Room in Dodge City, is available now.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I am wide awake when I see artist books.”

Ed Ruscha, Metro Mattress #4, 2015, Acrylic and pencil on museum board paper. 40 1/8 x 60 inches. Copyright Ed Ruscha, Courtesy of the artist, Gagosian Gallery and Sprueth Magers

Stephanie LaCava on Ed Ruscha’s Metro Mattresses

The following is from a letter Ed Ruscha wrote on February 25, 1966 to John Wilcock, a publisher who asked Ruscha to write about his books:

The only thing I can say about my books is that I have a certain blind faith in what I am doing… I am 28 and am mainly a painter (in Ferus stable). One important thing is that I do not cherish the print quality of a photograph. To me the pictures are only snapshots with only an average attention to clarity. The only distributor I have is Wittenborn’s in N.Y.C. They will actually buy a certain amount of books without consignment…

This is a charming prologue to an exemplary career. Fifty years later, it’s difficult to get a hold of Ruscha's early books, and impossible save for a certain price. The books Ruscha made in the 60s and 70s are largely credited with a reinvention of the genre. They all feature photographs: images of gas stations, small fires, swimming pools, palm trees, cacti, LA apartments, buildings or parking lots, Dutch bridges, babies or film stills, and Ruscha’s record collection.

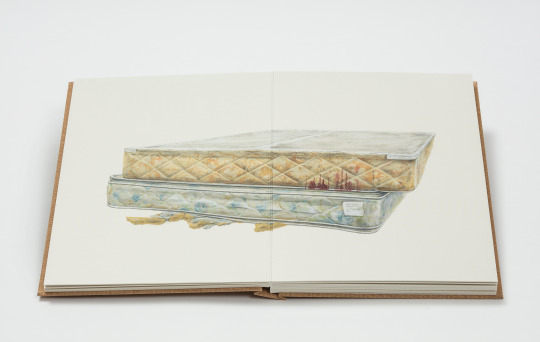

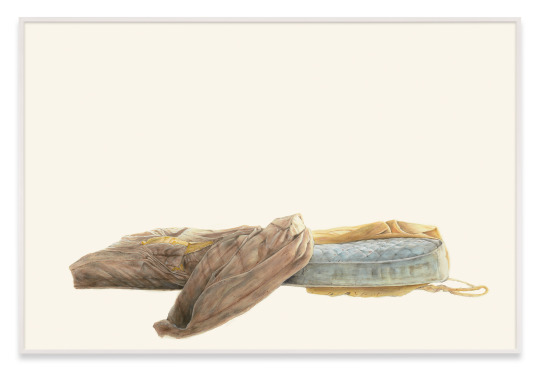

Unlike the others, Ruscha’s latest book, Metro Mattresses, features no photographs. Inside are twelve reproductions of the acrylic and pencil mattresses rendered on museum board paper as they were shown at last year’s Metro Mattresses exhibition. Ruscha and I emailed about Metro Mattresses last December, on his 79th birthday.

—Stephanie LaCava

Ed Ruscha, Metro Mattress #8, 2015. Acrylic and pencil on museum board paper. 40 1/8 x 60 inches. Copyright Ed Ruscha, Courtesy of the artist, Gagosian Gallery and Sprueth Magers

STEPHANIE LACAVA: Is there an implied narrative in the mattresses?

ED RUSCHA: There is no story line with the arrangement of images in the book. These mattresses began catching my attention as I moved around the city, especially Hollywood. They became my “clown” paintings. Clown paintings, in general, might be universally detested for what they are, but I began seeing mattresses as sad, and yet humorous subjects like clowns.

Ed Ruscha, Metro Mattress #9, 2015, Acrylic and pencil on museum board paper. 40 1/8 x 60 inches. Copyright Ed Ruscha, Courtesy of the artist, Gagosian Gallery and Sprueth Magers

SLC: Why not photos of the mattresses?

ER: A shift from photographs to painted images gave me a vision of another kind. The images were pampered with paint rather than with a camera. However, this left the book with a feeling of street objects being interpreted within the confines of a studio rather than being grabbed from the street itself.

Ed Ruscha, Metro Mattress #4, 2015, Acrylic and pencil on museum board paper. 102 x 152,5 cm, 40 1/8 x 60 inches. Copyright Ed Ruscha, Courtesy of the artist, Gagosian Gallery and Sprueth Magers

SLC: What do you think is most vital and important about artist's making books? Has this changed since you began your practice?

ER: I am wide awake when I see artist books. Here are people using actual ink on paper in the eventual age of total digital. For this reason I am retaining my hope and expectation of more books.

Material taken from the Roth Horowitz books on Photography put together by Andrew Roth in 1999.

Read Part 1: A Conversation with Seth Price

Read Part 2: A Conversation with Paul Chan

Read Part 3: A Conversation with Alissa Bennett

Read Part 4: A Conversation with Ed Atkins

Stephanie LaCava is an author and journalist living in New York City.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who Will Think of the Children?

Jim Knipfel on Satire and Children’s Books

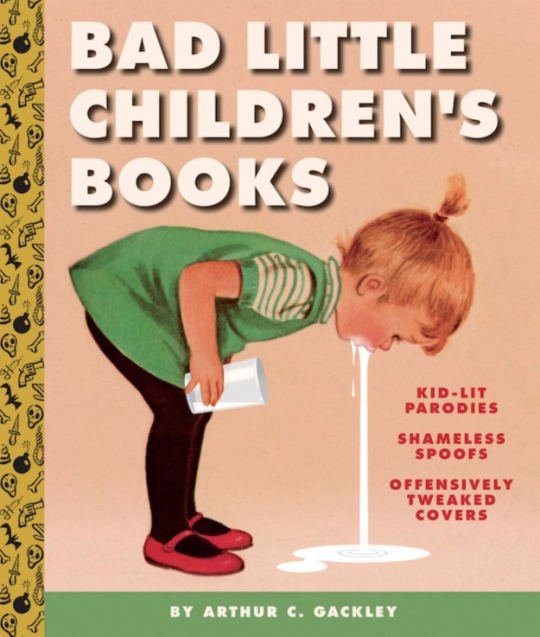

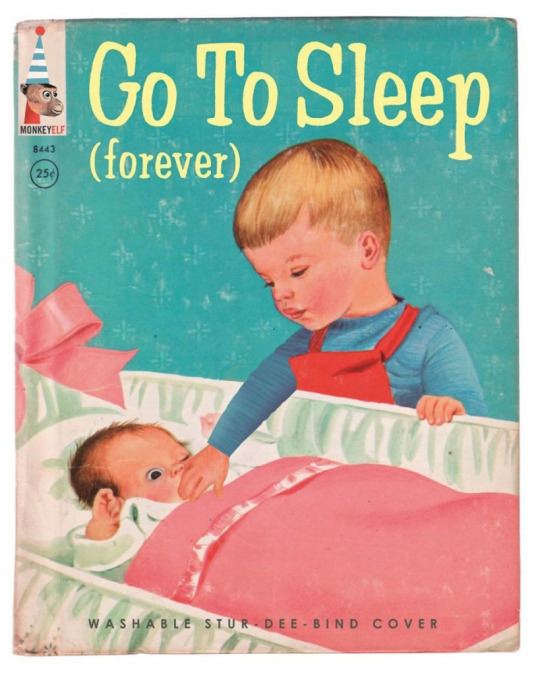

This past September, the Abrams’ imprint Image, which specializes in illustrated and reference works, published a novelty book entitled Bad Little Children’s Books by the pseudonymous Arthur Gackley. The small hardcover, which itself quite deliberately resembled a little golden book, featured carefully-rendered and patently offensive parodies of classic children's book covers. Instead of happy, apple-cheeked tykes doing pleasant wholesome things, Gackley’s covers featured kids farting, puking, and using drugs. Others included children with dildoes and racially inflammatory portrayals of Middle Eastern, Asian, and Native American youngsters. The book was clearly labeled a work of satire aimed at adults, and adults with a certain tolerance for bad taste and crass jokes.

Upon its initial release it received positive reviews and sold fairly well. Then in early December, a former librarian named Kelly Jensen posted an entry on Bookriot entitled “It’s Not Funny. It’s Racist.”

“This kind of 'humor' is never acceptable,” Ms. Jensen wrote. “It’s deadly.”

Jensen’s rant circulated quickly across social media, and Abrams suddenly found itself besieged by attacks from the outraged and offended, who assailed Gackley for creating the book in the first place, and the Abrams editorial board for agreeing to publish it.

“There is a difference between ‘hate speech’ and free speech,” one outraged member of the kidlit comunity wrote on Facebook. “In the same way, you cannot yell ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater just because you feel like it. This book was in very bad, insulting, racist taste, and designed to look like a children's book. How is that a good idea? Children are too young to understand this as parody. If it's for adults, why is that even funny? Oh, I guess if you are a racist you would think it's funny.”

Another tweeted, “Sounds like something that should've been completely ignored and removed before it hit the shelves. Just because we have the freedom of speech, it can be taken way too far.”

Still another confused and enervated soul wrote, “Argue all that you want, but this particular book was for children yes? Or no? If it was, does that mean we should allow and subject young children to gratuitous violence, gore and pornography? And what age is it acceptable? Does this mean we have to start putting PG-14 on printed material and make it mandatory because certain writers can't conduct themselves with a moral scale?”

Another angry reader summed it up quite simply by posting, “Freedom is bullshit, literally.”

[Note: As much as possible, the spelling, punctuation and grammatical errors which peppered the above posts have been corrected here for the sake of simple comprehensibility.]

Although Abrams initially stood by Gackley and the First Amendment right to offend, and had received the public support of several anti-censorship organizations, by December tenth the noise had simply grown too shrill. Mr. Gackley, maintaining to the end his intentions had been grossly misinterpreted, admitted there was no way to salvage things, and asked that Abrams not reprint the book. In a statement, Abrams announced they would be complying with his wishes. Although Bad Little Children’s Books was not banned in any official capacity, it had all but completely vanished from online booksellers within a few days after the announcement. Used copies, while available, are now selling for outrageous prices.

At the same time that this was happening, there were also calls to ban the (real) children’s books When We Was Fierce and A Birthday Cake for George Washington. The invented slang used in the former was interpreted as racist by some parent groups, and the latter was attacked for its historically inaccurate portrayal of the daily lives of slaves on Washington’s estate. Meanwhile, a mother in Tennessee led the call to pull Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks from the local school system. The New York Times bestselling biography, which concerned a Baltimore woman whose massive cervical tumor had become the invaluable source of several generations worth of cell lines used by cancer researchers, was being taught in local high schools as a means of educating students both about cancer and about racial issues within the medical community. The Tennessee mother calling for its removal, however, found the book pornographic.

Point being, I guess, that certain sectors of the population harbor an insatiable, even desperate desire to be shocked and offended by something they’ve read, seen, or even heard about, and the drive to ban these things (made much easier with the advent of social media) will likely always be with us. But back to the Gackley for a moment. Reading through the enraged postings aimed at Abrams, a number of the offended make the point that they are not attempting to censor, but are merely exercising their own First Amendment right to criticize. That’s fine and understandable. But the crux of the matter is that these people would be much happier if the book never existed in the first place, and considered Abrams’ decision a glorious victory for their cause.

Let’s try to put it in some sort of semi-comprehensible historical context. Dark and occasionally tasteless adult-oriented satires of children’s books, television and toys have been with us about as long as media aimed specifically at the innocent set. We just can’t help ourselves. Present us with the doe-eyed lukewarm treacle of the Smurfs or Care Bears, and some of us will instinctively reach for a baseball bat. In the case of Bad Little Children’s Books, the outrage in many instances seems to be sparked less by the content than form, and the fear that the book might actually be mistaken for legitimate kidlit. So here are a handful of similar cases from the last half-century. While reactions and results differ wildly, a certain historical pattern does seem to emerge.

Ralph Bakshi’s 1972 animated feature Fritz the Cat, based on the R. Crumb character, became notorious overnight for being the first theatrically-released cartoon to receive an X rating from the MPAA. What people tend to forget is that the film received the distinction not on account of its sexual content, nor because it included characters who were overtly racist, misogynistic drug addicts who cursed a lot. The real problem was the film featured cute and fuzzy animals who were racist, misogynistic drug addicts who cursed a lot, and had sex. The MPAA board was afraid people would see the cartoon poster and stroll into the theater, family in tow, expecting the latest Disney opus. By modern standards the film should have received nothing more than an R rating, but the damning “adults only” designation was an effort to avoid any confusion. It didn’t matter. People saw the X rating and immediately concluded Bakshi had made a hardcore cartoon in a diabolical effort to corrupt the nation’s youth. Although the publicity attracted large audiences and earned the film an undeniable bit of underground cred, that same publicity did irreparable damage to Bakshi’s career. For decades afterward, even while trying to redeem himself with the family-friendly Mighty Mouse cartoon series for TV, he found himself labeled a racist, sexist pornographer determined to get America’s young people hooked on heroin—charges leveled at him mostly by people who had never seen Fritz the Cat.

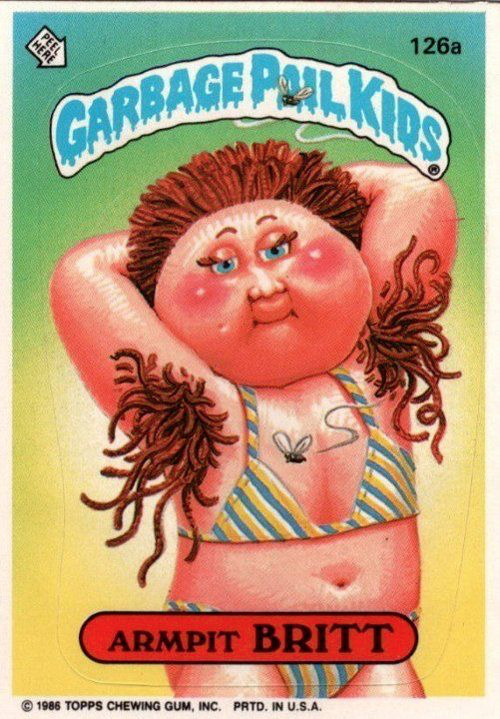

Long before he won a Pulitzer for Maus and became a regular contributor to The New Yorker, cartoonist Art Spiegelman spent twenty years working for the Topps trading card company. Among other things, he was one of the primary creative forces behind Topps' wildly popular and wickedly subversive Wacky Packages series, which satirized American consumer products. In 1985, Topps attempted to arrange a licensing deal to release a series of trading cards based on Cabbage Patch Dolls, which were all the rage at the time. Finding licensing fees had already gone through the roof, they decided instead to release a Wacky Packages-style parody. As it happened, an unreleased Wacky Packages design called Garbage Pail Kids was already on the boards, so they ran with it.

Spiegelman and the involved artists took the basic design of the cuddly and adorable plush dolls beloved by all the world and twisted them into deranged monstrosities covered in snot, vomit, oozing sores and bugs. From the moment they hit convenience store checkout counters, the GPK stickers were outrageously popular. Although some school systems banned them as an unwelcome distraction and more than a few parents were mortified and disgusted that any sick individual would do such a horrible thing to something so innocent and cuddly, there was no organized grassroots effort to censor the stickers on moral grounds. Topps' only real trouble came in the form of a copyright infringement suit filed by the Cabbage Patch Dolls’ creators, Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc.

Topps’ argument that what they were doing was clear and obvious parody (and therefore protected under the First Amendment) didn’t quite cut it. The suit was settled out of court, with Topps agreeing to alter the Garbage Pail Kids logo and basic character design so as to avoid any possible confusion with the original dolls. The stickers continued to come out, and went on to inspire an animated television series, a feature film, a book and an unholy array of merchandise ranging from trash cans to sunglasses. In the end, it could easily be argued that over time the Garbage Pail Kids had more of a lasting impact on the culture than their inspiration.

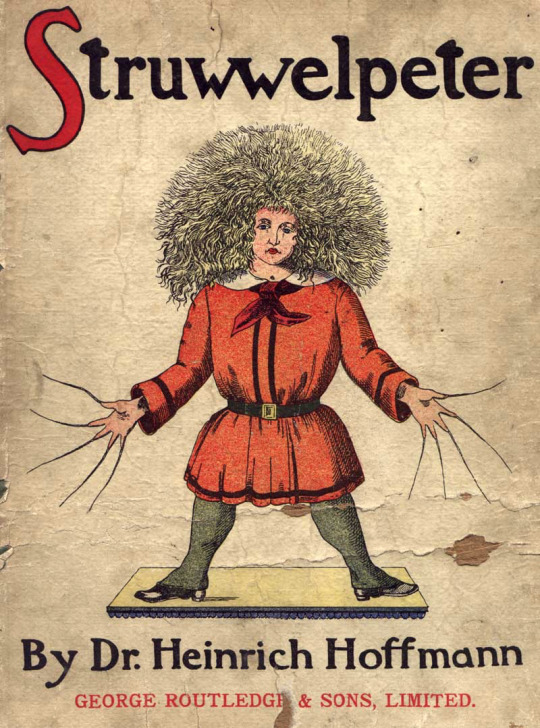

Struwwelpeter was first published in Germany in 1845. The cautionary and terrifying collection of nursery rhymes (with graphic accompanying illustrations to drive the point home) warned children that if they sucked their thumnbs, didn’t eat their dinner, didn’t clean themselves up properly, mistreated their pets or threw tantrums, a horrible fate awaited them. The book became a standard instructional volume in most German households with young children. In 1898, a similar but decidedly British version was released in England under the title Shockheaded Peter, and was nearly as popular. Nobody it seemed thought much about presenting naughty children with images of potential disfigurement or death. The book helped keep the little buggers in line.

In 1999, American indie publisher Feral House released a gorgeous new edition of Struwwelpeter, complete with new illustrations, interpretive and historical essays, and assorted bowdlerized and satirical versions of the nursery rhymes which had appeared over the years. Feral House, which had always prided itself on publishing dangerous and controversial works, soon found this simple history and analysis of a once popular if disturbing children’s book could be just as troublesome as their books by notorious British serial killer Ian Brady or the Church of Satan’s Anton LaVey.

“Yes, we had minor trouble with Struwwelpeter,” says Feral House founder and publisher Adam Parfrey. “But most of that was put to rest when bookstores simply refused to carry the book. I guess 21st century Americans are more touchy than the Germans of yore. For a while, a couple chains and many independent bookstores stopped carrying the Anton LaVey books we published after Geraldo Rivera put on those sensationalist programs about Satanism... I credit Marilyn Manson for putting an end to that crap. After he spoke out about it, so many people went into bookstores to order them that the stores saw best to get them back into their shops. Time passed, and the crazy ideas receded.”

Parfrey also sees a potential connection between the backlash Abrams suffered over Bad Little Children’s Books and the present brouhaha over what has been termed “fake news.”

“Right now there’s a good bit of madness going on with Trump-loving crazies, including Alex Jones and Infowars building up this idea that Hillary Clinton and John Podesta are torturing and killing children…and they’re pointing at Marina Abramović, too. That’s a big deal on Facebook at this instant. And anyone who poo-poos this story is being accused of covering up kiddie killing. I can see how this sort of madness can amplify into the book trade, a situation where parodies are mistaken for outright kiddie torture. Sad, isn’t it?”

As a final example, in 2010 Simon and Schuster published my book These Children Who Come at You With Knives, a collection of darkly comic fairy tales aimed at adults. Across roughly a dozen stories written in traditional fairy tale formats (though with more cursing, gratuitous gore, and uncontrolled bodily functions), assorted anthropomorphized animals, magical creatures, human children, the elderly and the dull-witted come to various terrible ends. The book received decent reviews and publicity, but there was no outcry, no controversy, and no one insisted the book be banned in order to protect the innocent. Meaning, of course, that I didn’t sell millions as a result of the hoo-hah. Christ, I’ve even heard from people who use them as bedtime stories for their own kids. Dammit! What the hell did I do wrong?

I think I made two deadly mistakes. First, despite my best efforts to the contrary, my publisher decided to release the book without illustrations, meaning it could never possibly be confused with an actual children’s book. More devastating still, I was cursed with bad timing. These Children Who Come at You With Knives was released halfway through President Obama’s first term, and while there was certainly a good deal of rancor in the air, satire was still a viable form and accepted as such, at least among the literate.

In different eras and in different ways, all the above examples were damned by a public inflicting its own preconceived notions upon works of obvious satire, insisting they be what the public believed them to be instead of what they actually were.

By the time Bad little Children’s Books was released, the world had become too ridiculous, too absurd, and as a result we lost our sense of humor. There was simply no longer any way to lampoon our chosen leaders or our own insecurities, with the world itself poised and ready to top us at every turn. In short, the book’s publication coincided with the precise moment satire breathed its last, meaning readers had no choice but to take Gackley’s work, as Parfrey points out, at face value. Lucky bastard.

Jim Knipfel is the author of Slackjaw, These Children Who Come at You with Knives, The Blow-Off, and several other books, most recently Residue (Red Hen Press, 2015). his work has appeared in New York Press, the Wall Street Journal, the Village Voice and dozens of other publications.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Think of a pencil being more like a cup of coffee rather than a pen.”

An Interview with Joey Cofone of Baron Fig

As far as pencils are concerned, I’m a late adapter. I made the switch from a fountain pen (how pretentious, I know) after finishing an essay by Mary Norris on her quest for the ideal No. 1 pencil (contrary to the cabal of No. 2 makers at Ticonderoga, they do exist, and are nigh impossible to find). It shows how deep pencil-freak culture goes that if you’re too occupied to maintain your pencil-point, you have the option of mailing your dulled graphite to David Rees, author of How to Sharpen Your Pencil, to be professionally sharpened. But is there anything more to be said about pencils? Can the pencil be re-conceptualized?

For minimalist pencil-designed Joey Cofone, the answer is an all-caps yes to both questions. Cofone has taken 1st place in the 2013 AIGA CMD-X competition, while Print Magazine named him one of 15 designers under 30 to watch.

The thing to understand first off about Cofone is that he likes simplicity a lot. The co-founder of Baron Fig, a New York-based maker of notebooks, Cofone has recently delved into reinventing the pencil. Or revolutionizing it. At the very least, he’s produced a damn fine instrument to write with and to hold.

The fittingly named Archer has a design that’s extremely clean-lined, forsaking the ferrule and even the eraser in pursuit of lightweight practicality. It’s also incredibly aromatic.

—Michael Peck

BLVR: What got you into paper and notebooks?

JOEY COFONE: Several years ago, back at the School of Visual Arts here in New York City, I had realization that changed my life. Walking through the design department and taking a look at my fellow classmates’ tools, I noticed something: each of us was using two tools—a laptop and a notebook—to design. The laptops were all the same, MacBooks, but the notebooks were all different brands, sizes, paper types, and so on. I was intrigued. Why was there ubiquity with one tool but no loyalty to the other?

I went home and checked out my own bookshelf, and lo’ and behold all of my notebooks were different. There was this unspoken search for the right notebook that was going on all around me. Eventually my Co-founder Adam Kornfield joined the mix, and together we talked to thinkers all over the world, asking them one question: What do you like in a sketchbook or notebook?

Out of the five hundred plus cold-emails, we received a whopping 80% response rate. It turns out others were on the same search as us—and they had a lot to say. We used all that feedback to design the first community-inspired notebook, the Confidant, and put it on Kickstarter. At the end of thirty days we sold almost ten thousand notebooks and raised over $150k. That was just over two years ago.

BLVR: How did the name Baron Fig come about?

JC: I had this hankering for the word “Baron.” No idea why, such is life. I took the word to my co-founder Adam and our friend Scott, and told them that it needed a second word. Scott immediately, without hesitation, said “Fig.” Adam and I were confused—what does it mean?—even Scott didn’t know why he said it. Somehow it stuck, but I wasn’t happy with it. How could a company about thinking, about infusing meaning into creativity, not have a name with meaning itself?

For the next few weeks I wrote down hundreds and hundreds of possible names, but none stuck like Baron Fig. Finally, pretty much at wit’s end, I decided to look up the origins of baron and fig. Baron was a symbol of Apollo and Fig was a symbol of Dionysus—brothers that represent order and chaos. The name essentially symbolizes balance, of having the discipline to work hard but also the impulse to play, which is the essence of the creative mindset.

BLVR: What prompted the leap into pencil-making? Were there specific models that influenced the design of the Archer?

JC: I’m a minimalist designer. Hell, I’m a minimalist exister, if there is such a word. I like everything simple, fluid, clear. Clutter and excess drive me nuts. Even when I was a kid, I always wanted things to be just right. I used to go around the house and organize each room as if they were showrooms on display. Lamps squared with the edges of tables, stove tools arranged from longest to shortest, you name it and I was all over it.

The Archer pencil was sort of a minimalist dream come true. I’ve always wanted to design a pencil—they’re like little creative wands—and it took our team over a year to hone in on the right production quality. In the meantime I designed dozens of versions before landing on the Archer you see today, each iteration a little more refined and simpler than the ones before it.

BLVR: Minimalism is definitely a noticeable trait, and it seems like the Archer is something of an ultimate statement of this simplicity. How does one go about re-conceptualizing the pencil?

JC: I don’t know how other designers do it, but I keep iterating until things feel right. Sometimes it’s quick, sometimes it takes 82 versions like the Confidant notebook’s packaging. My goal is to isolate and preserve the best elements, improve the weak ones, and look to my inner self’s gut response to see if the new outcome pleases or not. Rinse and repeat. My old teacher and designer James Victore has a good line about this: “In the particular lies the universal.” Solve your problem—and delight yourself—and you’ll do the same for others.

BLVR: The Archer, besides its other greatnesses, smells so good I have to pause what I’m doing and take a hit. How much wood did you have to test/sniff to make the best choice?

JC: I hear you. We try to take our hits when no one is looking. Sometimes you can find Adam near the stock shelves face-deep in a box of them. It’s definitely an issue.

BLVR: You mentioned earlier this idea of ubiquitous loyalty when it comes to laptops, etc. Pencils are sort of marked by promiscuity—once you’re done with one, you just pluck another from the box. So how do you hope to gain that kind of loyalty with the Archer?

JC: Think of a pencil being more like a cup of coffee rather than a pen. We all find our favorite coffee and stick to it. Sure, the cups run out, but there’s always another one waiting—and you know it’s going to be just as good as the ones that come before it. Quality, reliability—they’re both extremely important in designing a consumable, especially a tool that helps us do our work or hobby.

BLVR: For pencil nerds like myself, how does the Archer differ, and improve upon, something like the Palomino Blackwing?

JC: I get asked this a lot. We put major emphasis on community feedback, and design accordingly. Since we launched Baron Fig we’ve tweaked and redesigned every product directly based on the ideas that come our way from our customers. When we say “Designed by the community,” we mean it. As far as the Archer goes, they’ve been a requested product since day one. Each Archer is extremely high quality, better than anything available at their price point of $15 per pack. And, if I do say so myself, sexier than any pencil, period.

BLVR: It’s definitely a sexy pencil.

JC: Thank you.

BLVR: Pencils, packaging—it’s so minimalist it’s sans-serif, without a stray line in sight, the Phillip Glass of writing implements (I could go on). But I do find myself a little thrown off by the lack of an eraser. Was there a debate to excise the eraser?

JC: Well said. Since launching the Archer I’ve been asked this question often—"Why did you remove the eraser? What’s your thinking?“—as if I’ve committed an atrocity. There’s a disconnect, though, between how people say they feel about erasers versus how people actually feel about them. When’s the last time you used an eraser on a pencil and thought to yourself, "Damn, this eraser is great”? I don’t think it happens. They’re pretty much crap, every one seems to leave marks on the page, gets dirty and blemished, and in the end delivers an underwhelming experience.

So I nixed it. Boom, goodbye eraser at the end. With that out of the way now we can actually deliver a quality eraser on the side, one that doesn’t mark up your page and isn’t limited to the lifespan of the pencil itself.

BLVR: What do you see the Archer going into the world to achieve?

JC: Everything. Imagery and language are some of the oldest and most glorious technologies known to man. Technology? What? Yes, technology. But I’m digressing—what do I hope for the Archer to achieve? For these pencils to be the vehicles of communication, of images and words, that affect the world. Ideas are powerful, writing instruments are the means by which they’re communicated. On our site, at the top of the Squire pen page, it explains that a writing instrument “…grants the power to move entire nations, to touch people’s hearts and souls—to make something from nothing.” And I mean every word of that.

Michael Peck is the author of The Last Orchard in America. His work has appeared in Tin House, LA Review of Books, Pank and elsewhere. He lives in Oregon City, where he deals in rare books.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELECTRIC BLUE

All photographs by the author.

Kim Wood on David Bowie

1.

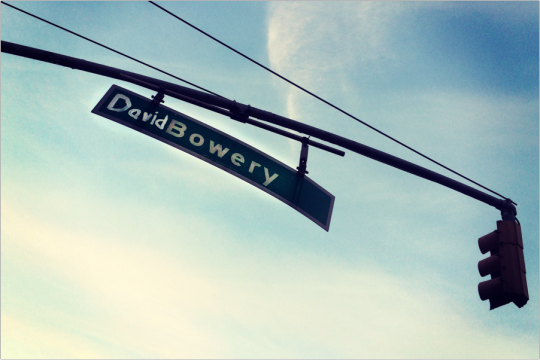

There are roughly ten blocks between the theater where David Bowie watched rehearsals for Lazarus, and the studio where he recorded Blackstar. In his last years, we both lived between them, on opposite sides of Houston Street.

My side is the Bowery, known in real estate speak as NoHo (North of Houston). On the street where I live—a two-block stretch of 3rd Street known as Great Jones—is a chandeliered butcher shop occupying the spot where Basquiat worked, and died, of a heroin overdose. Twenty years before his time, Charlie Mingus’ heroin-addicted presence on this corridor is said to have birthed the term jonesing.

I’ve passed a decade in Brooklyn, but never before now lived in Manhattan and love being a downtown kid, stepping through the door and onto crowded streets, passing CBGBs—now a skinny pants boutique I’ve never entered—on my way to buy groceries, or borrowing books from a library branch housed in the one-time factory of Hawley & Hoops’ Chocolate Candy Cigars—that Bowie lived above, in a modern penthouse perched atop the turn of the century brick building.

For twenty-four months, barring the occasional trip to Central Park, I’ve lived below 14th Street and in this time Bowie loitered here too, sipping La Colombe’s double macchiato, fetching chicken and watercress sandwiches at Olive’s, or dinner supplies at Dean & DeLuca. One day I’d catch him on the street, I figured, hailing a cab or taking out the recycling in his flat cap and sunglasses, and when I did my well-worn New Yorker discretion would be jettisoned as I tried, and likely failed, not to cry.

I didn’t, of course, know that for most of the time we were neighbors David Bowie was dying. Today I walk the familiar stretch of blocks to his building, eyes tearing, I tell myself, from the frigid, bone-dry air. At the front entrance, a group of fans stand gutted, surrounded by news trucks, generators, vulturing reporters.

A growing pile of daisies, tulips, roses, daffodils leans against the wall, along with a few photographs, a pair of silver glitter heels, a Jesus candle with Ziggy Stardust face. Tucked here and there are handwritten notes: Look out your window, I can see his light and We are all stardust and Hot tramp, we love you so.

Everyone here, news crew aside, feels known somehow, the mood is gentle, polite, quiet. Too quiet, I realize, when someone plays “Life On Mars?” from a tinny smartphone speaker. As the closing strings swell, a woman turns to me to say through tears, “I love this song!” All I can do is nod, “I know!” and take comfort among fellow kooks.

A pair behind me wonders aloud about a “world without Bowie,” and while I know what they mean—the way some people feel like a force and invincible—you could argue we’ve been living in such a world for a long while. David Jones-ing.

2.

Three days earlier, on the night of Bowie’s 69th birthday, I danced in my kitchen to the foppish, falsetto, “‘Tis a Pity She Was a Whore,” delighting in his rude lyrics and wild whooping. Later at a dinner hosted for the birthday of a friend, I commented on Bowie’s continuing fixation upon mortality, but also his energy, sly humor, return to form, exclaiming, not tentatively, “Bowie’s back!”

I was thrilled he’d finally slipped the ghost of what he called, “my Phil Collins years.” In one of the endless interviews now flooding my screen in text and video, he explains, “I was performing in front of these huge stadium crowds and at that time I was thinking ‘what are these people doing here? Why did they come to see me? They should be seeing Phil Collins.’ And then that came back at me and I thought, ‘What am I doing here?’ It’s a certain kind of mainstream that I’m just not comfortable in.”

Like the divisiveness of fat and skinny Elvis, there were those of us who fancied ourselves glittering, androgynous, apocalyptic half-beast hustlers who bought drugs, watched bands and jumped in the river holding hands, and there were others, contentedly jazzin’ for Blue Jean.

When, in your Golden Years, your mentor of not only music but all things relevant—art, clothes, books, films—enters his Phil Collins Years, suddenly high-kicking in Reeboks and staring in Pepsi commercials, how not to feel betrayed?

I took it personally, coining the unforgiving term David Bowie Syndrome. As a burgeoning artist, I feared (a scaled-back version of) his creative arc with my whole heart—reaching the greatness of Bowie’s 1970s only to follow it up with Let’s Dance. To say nothing of Tin Machine. Like many old-school fans, I’d stopped tuning in to modern Bowie to keep my vintage Bowie flame flickering.

In my most youthfully caustic moment, I joked that Bowie’s personal Oblique Strategies deck—that famous stack of cards, creative prompts such as Ask your body, Abandon normal instruments, and Courage! allegedly used when Bowie and Brian Eno recorded Low and Heroes—should be made up of cards that all read, simply: Call Eno.

Unfair, untrue. Kindly allow this counterpoint mea culpa admission: I secretly love the ham-fisted, cringtastic video for Dancing in the Street.

3.

On the third day after Bowie’s death I step outside, wondering if I’ll still hear his presence hum. Just feet from my front door I’m greeted by his face gracing one of two large posters advertising Blackstar. Well hey there, Mr. Jones.

They’re wet with wheat paste and like a teenage fangirl I consider stealing one, but then notice a smaller poster hung next to them, featuring the Sesame Street characters peering out joyously, encouraging me to attend an event entitled… Let’s Dance!

I accept Bowie’s cosmic joke, had it coming I suppose, and briskly hoof it to Union Square where at the farmer’s market I find apples, apple cider, cider doughnuts and not much else. My gloveless fingertips smart as I pocket change and consider the possibility that the visitation was an invitation to dance through the sorrow. A bit maudlin perhaps, but then, so was Bowie.

When I return home the Blackstar posters are gone. In under an hour someone has pasted them over with clothing and gym ads—leaving all the posters on either side for the length of the street untouched. Like Steppenwolf's Magic Theater, the message—whatever it was—had appeared and just as quickly vanished.

My feet walk me to Bowie’s memorial, which has exploded in a heap of bouquets, black bobbing Prettiest Star balloons, cha-cha lines of platform heels, disco balls, eye shadow, quarts of milk, British flags, drawings and paintings of Bowie’s many incarnations, fuzzy spiders, bluebirds, boas, vinyl copies of David Live annotated Forever in thick silver marker.

A giant orange tissue paper flower hangs from a nearby tree, electric blue eye at its center, petals edged in lyrics: Give me your hands, because you’re wonderful! Let the children lose it, let the children use it, let all the children boogie.

Here and there are tucked personal notes: You taught me that weird = beautiful, and: When I was a teenager I wished I could check off “David Bowie” for both my gender and my race. I still do.

“Taking away all the theatrics…” Bowie said, “I’m a writer. The subject matter…boils down to a few songs, based around loneliness, isolation, spiritual search, and a looking for a way into communication with other people. And that’s about it—about all I’ve ever written about for forty years.”

Perhaps, then, my “Let’s Dance” visitation was an anti-message, a warning against wasting creative juju by pandering for cash. Of course, Bowie made not a dime (relatively, and thanks in large part to shifty management) from his artistic era I find most inspiring. The seed of the fortune that brought him financial security was that very song. So what then?

When I return home, Bowie’s spot on the wall has been papered over yet again, all white this time, as though to say, as he has when pressed to interpret his lyric’s meaning, “nothing further,” “you figure it out,” “space to let.”

4.

I rise before the sun, pull on bright turquoise tights and red clogs and walk the cobblestone of Lafayette Street in the dark. Collar up, breath ghosting, I feel as I secretly do in all such moments, like the cover of Low, or The Middle-Aged Lady Who Fell to Earth. Car headlights slide over me as I approach the memorial that is, it appears, being dismantled.

I quickly make the photograph I awoke imagining: my platforms meeting Bowie’s shore of flickering candles, cigarette butts, stray boa feathers, sea of glitter. Beside me a sweet lone man sorts out the dead flowers, shuffling handmade things to one side, candles to another, not tossing it all as I first suspected, but tidying up, preparing for another day.

What drew me into this frigid darkness, half dressed in pajamas? Perhaps a need to meet Bowie toe to toe, promise to honor the contract, all in, heart wide, funk to funky.

Put on my red shoes and dance the blues.

“I don’t think (the act of creation is) something that I enjoy a hundred percent. There are occasions when I really don’t want to write. It just seems that I have a physical need to do it...I really am writing for myself.”

Before Blackstar, the last time I know of Bowie creating under extreme duress is when making the album Station to Station—which coincidentally also opens with an epically long titular song wherein a man yelps from the darkness, singing with pride and pain about a fame that has isolated him beyond measure.

As the Thin White Duke, Bowie sings with bitter irony, It’s not the side effects of the cocaine! I’m thinking that it must be love! It’s well known that Bowie, living for a year (1975-1976) in his despised, self-chosen, wasteland of Los Angeles, had fallen victim to a kind of Method Writing, unable to escape in life the character he’d crafted to hide behind on stage.

Subsisting on a diet of cocaine, chili peppers and milk, he grew paranoid, hallucinating, allegedly dabbling in Black Magic and storing his jarred urine in his refrigerator. I was six years old at the time, living less than a mile from Cherokee Studios where Station to Station was in session, and smudging my mother’s brand new Young Americans vinyl with powdered sugar fingerprints.

He said of the following album, Low, “It was a dangerous period for me. I was at the end of my tether physically and emotionally and had serious doubts about my sanity. But I get a sense of real optimism through the veils of despair from Low. I can hear myself really struggling to get well.”

It’s the pale, shimmering hope that makes Low my favorite of all of Bowie’s offerings, but for Station to Station’s Duke of Disillusion it’s too late—for hate, gratitude, any emotion. It’s not, however, too late to lay himself bare in the work: there’s no reach for sanity, just a man collapsing while still directing, as the camera rolls.

Blackstar has been called a gift, and on “Dollar Days,” a song that describes his effort to communicate in the face of death, Bowie breaks the fourth wall to address this directly: Don’t think for just one second I’ve forgotten you/I’m trying to/I’m dying to(o).

I believe as an artist he had no choice, no other way to confront his circumstance other than to talk himself through it, put it in the work.

The profound generosity of Blackstar, and a vast swath of Bowie’s creative output, is that in this most intimate conversation with death, god, time, himself, we’ve been invited to listen in.

5.

What makes a good death? Bowie withdrew from the public in the last decade and was characteristically silent regarding his illness, in this tell-all age (that owes him not a little for its status quo “tolerance” of Chazes and Caitlyns). He was also, in his time post-diagnosis, compelled to make his most raw and exposing work in years, and between the play and album, likely spent a long part of each day in their pursuit, while presumably also tending to his needs as a father, husband, friend, man.

In Walter Tevis’ book The Man who Fell to Earth—the basis of Nicholas Roeg’s film that inspired Bowie’s production Lazarus—stranded, despondent space alien Thomas Jerome Newton records an album called The Visitor: we guarantee you won’t know the language, but you’ll wish you did! Seven out-of-this-world poems! Newton explains it’s a letter to his family and home planet that says, “Oh, goodbye, go to hell. Things of that sort.”

Bowie’s seven-song swansong, Blackstar, is rather more generous, and from a writer notorious for lyrical slipperiness, layered meanings, a cut-up technique (copped from Burroughs) that spawned lines about Cassius Clay and papier-mâché, its text is frequently plain-spoken and direct.

Even my favorite frolic sounds a combative calling down of his illness, time: Man, she punched me like a dude/Hold your mad hands, I cried/She stole my purse, with rattling speed/This is the war. It would not be the first time Bowie referred to Time as a “whore.” (see: Aladdin Sane.)

In the title video’s most vivid sections, Bowie becomes god—less vengeful than dismissive—singing, from heaven’s attic, a swaggering takedown of Bowie himself: You’re a flash in the pan, I’m the great I am. (From Exodus: And God said unto Moses, I AM THAT I AM: and he said, Thus shalt thou say unto the children of Israel, I AM hath sent me unto you.)

His button eyes in both videos suggest a puppet, and so the presence of a puppet master, but I don’t read these images as signs of deathbed conversion. Bowie was a spiritual seeker who borrowed magpie style—in this case from Egyptian, Kabalistic, Christian and Norse iconography—to create a language to give voice to his fears and dark entries.

“If you can accept—and it’s a big leap—that we live in absolute chaos, it doesn’t look like futility anymore. It only looks like futility if you believe in this bang up structure we’ve created called ‘God’.”

In his last gestures Bowie answered not God, but himself, regarding the way he’d lived, and in particular, as an artist. The pulse returns the prodigal sons suggests that the characters he inhabited—some regrettable, but not irredeemable—are with him as he assesses the intentions behind, and perceived short-comings of, his creative offerings: Seeing more and feeling less/Saying no but meaning yes/This is all I ever meant/That's the message that I sent/(but) I can’t give everything away.

In his almost unbearably haunting last video, it seems we’re finally invited to meet David Jones, or Bowie playing Jones. Jones the man lies in bed, clutching a blanket with those mortal, frightened hands. Nearby the writer manically, fretfully reaches for immortality, while Bowie the performer, dutifully dances to the end.

“There’s an effort to reclaim the unmentionable, the unsayable, the unspeakable, all those things come into being a composer, into writing.” “You present a darker picture for yourself to look at, and then reject it, all in the process of writing. I think that’s what’s left for me with music. Now I really find that I address things to myself. That’s what I do. If I hadn’t been able to write songs and sing them, it wouldn’t have mattered what I did. I really feel that. I had to do this.”

This morning I remembered where I'd seen the writer's austere, black and white striped costume before: the program for the 1976 Isolar tour, wherein Bowie self-consciously poses with a notebook or makes chalk drawings of the Kabbalah tree of life. Isolar is a made up word—and name of his current company—said to be comprised of isolation and solar.

I love this costume—a kind of artisan worker-bee uniform. There are satin kimono-sleeved ass-baring rompers for when its time to present the work, but when making it, roll up your revolutionary sleeves and get to it.

1976 saw the success of Station to Station, the premiere of The Man Who Fell to Earth and the recording of The Idiot and Low. It was not the most grounded time for Bowie personally (to understate it), but arguably his most vital creatively, and this nod to the continuum of creative spirit seems to suggest that the artist dies, but through the work, like Lazarus, rises again.

6.

So what, then, is a Blackstar? Perhaps a marked man, a sly reference to Elvis’ song of the same name whose lyrics include, Every man has a black star/A black star over his shoulder/And when a man sees his black star/He knows his time, his time has come.

Although Bowie did not, as rumored, write “Golden Years” for Elvis, he did find (somewhat bashful) significance in their shared birthdays, took pains to catch his concerts, had his white jumpsuit copied to wear while performing “Rock and Roll Suicide,” modeled his own costume in Christiane F after Elvis’ ensemble in Roustabout, and perhaps his Aladdin Sane red/electric blue lightening bolt was inspired by Elvis’ signature gold one. Which is to say, he likely knew of The King’s “Black Star.”

Blackstar could also suggest the theoretical transitional state between a collapsed star and a singularity—a state of infinite value in physics, a metaphor for immortality.

I’m not a gangstar/I’m not a film star/I’m not a popstar/I’m not a marvel star/I’m not a white star/I’m not a porn star/I’m not a wandering star/I’m a star’s star/I’m a blackstar.

“Sometimes I don’t feel as if I’m a person at all...I’m just a collection of other people’s ideas.” Is Bowie simply claiming his right to throw off all mantles?

The car crash that is the documentary Cracked Actor opens with a reporter asking, “I just wonder if you get tired of being outrageous?” “I don’t think I’m outrageous at all,” Bowie throws back, miffed. The reporter persists, “Do you describe yourself as ordinary? What adjective would you use?” Bowie searches his brain for an appropriate response to the inane question and finally lands upon: “David Bowie.”

Or perhaps, as Isolar suggests, a Blackstar is someone hidden in plain sight. In an interview that seems more therapy session, with Mavis Nicolson in 1979, mostly drug-free and grounded Bowie speaks of the appeal of life in Berlin, whose physical wall seemed to mirror his psyche. Without referencing himself or the characters he’s inhabited, he describes an isolated figure who finds no home in the world, but instead creates “a micro world inside himself.”

When Nicolson suggests that as an artist Jones must keep himself from love, he rejects the idea outright, but when gently pressed about the demands of relationships in actual life and not “from afar,” he concedes, extending his arms before him like a shield, “No, love can’t get quite in my way, I shelter myself from it incredibly.”

The moment is so resonantly raw that the two break into manic humor, shifting to the story of his eye injury in a childhood fight over a girl, wherein he laughs and says, “I wasn’t even in love with her.”

In “Lazarus,” the dying Jones sings: everybody knows me now, and perhaps that is so, as much as it ever could be for a man who spent an artistic career in self-sustained exile.

And why shouldn’t David Jones have been—with the exception of a few deeply druggy years—free from the curse and blessing of being Bowie? What are we owed by our artists?

7.

Blue, blue, electric blue, that's the colour of my room.

The Bowie song that forever circles my brain describes a writer waiting for the muse, describing the loneliness and blessing of the electric blue of creation. Vishuddhi, or the electric blue throat chakra of Hindu tantra, is associated with the vocal cords, communication, creative expression, one’s inner-truth.

For sixteen months I lived in Berlin’s Schöneberg quarter, around the corner from 155 Hauptstrasse and the apartment that song was composed in and of. I’d pedal my bike past and nod to the ghost Bowie inside, still wondering and waiting for the gift of sound and vision.

It’s the seventh day since Bowie’s death, the final day of shiva I’ve sat beneath his window. I’ve never much understood funerals, always felt they were for a “living” that didn’t include me, but this has been different.

Over this week I’ve shared glances with occasional bleary-eyed oldsters coming or going from where I’m headed or have just been–there have been no young folk to speak of and no platform boots necessary to recognize the kooks.

Today, from a block away, I spy a pair of women making the pilgrimage. The taller of the two—who for one moment I mistake for Patti Smith—has Smith’s hair, a floor-length bright blue shearling coat and an armload of exquisite orange, flame-tipped roses.

Trailing my comrades I think of Smith’s line in Woolgathering when, upon being given a dandelion, she asks, “What could I wish for but my breath?”

At Bowie’s door the energy feels less personal, dissipating. After the roses-bearers depart, a lone woman and I stand shivering before the diminished pile of offerings framed by narrowed police barricades: plastic-wrapped bodega flowers and a few handmade items, the most prominent being a cigar box shrine with a Halloween Jack eye patch and what seems a bunch of random stuff tossed in. The woman plays “Starman” on her phone, and rather than poignant, it’s just sad.

A years later follow-up to his first solo release, “Major Tom,” “Starman” takes the isolation of planet earth is blue and there’s nothing I can do and turns it into an anthem where a cosmic DJ messiah tells us misfits not to blow it, ‘cause he thinks it’s all worthwhile.

The 1972 Top of the Pops performance famously featured Bowie’s flirty finger wagging at the viewer, and casually intimate embrace of Mick Ronson, which blew the minds of much of Britain and beyond and marked Bowie as a more than a one-hit wonder. I silently give thanks to many, including Bowie, not to live in a world where a rock and roll arm thrown over a shoulder can cause a stir.

Over the song’s fade out the woman shrugs and says something about bears—at least I think that’s what I hear. I smile and nod remotely, then realize she’s drawing my attention to the carefully rendered Ziggy Stardust teddy bear—complete with lightning bolt and guitar—hanging from the police steel.

This bear abrades me for no good reason. A few young women pass by on their way into American Apparel. “That was David Bowie’s house,” one says over her shoulder, and the other makes an “awww” sound like she might at the sight of a teddy bear, or the memorial of that musician guy that died the way people do—other people, older people. As they pause to take a selfie in front of Bowie’s memorial offerings I turn and nearly sprint downtown.

I learned in this week of Bowie Internet inundation that he trailed these streets too, often at dawn, in solitude, but right now I need Chinatown’s chaotic, smashing life. I’ll buy those killer clementine from that vendor on the corner, I think, and eggplant, scallion and ginger for supper.

I weave among cardboard boxes of dried silver fish and lotus root, tourists linked arm-in-arm in matching New York pom-pom hats, Chinese grandmas pushing plaid shopping carts in (Harold and) Maude braids. A man exits a hallway, arms loaded with red-ribboned funeral flowers. A chef in a paper hat leans against a wall, smoking beneath a pumpkin-sized, spinning dumpling.

Beneath crisscrossing wires strung with giant, glinting snowflakes, I warm my hands on a cup of milky tea and wonder when we’ll get winter’s first snow. Glancing up to cross Mott (the Hoople) Street, I wonder when the city’s details will cease to conjure Bowie.

I tuck dragon fruit into my sack, humming “Starman”—whose chorus melody is plainly lifted from The Wizard of Oz’s “Over the Rainbow.” Somewhere over the rainbow, bluebirds fly/Birds fly over the rainbow./Why then, oh, why can't I?

In performance, Bowie sometimes coyly sung a mash-up of these anthems of longing for belonging. On “Lazarus” he sings, seemingly of his death, This way or no way/You know, I’ll be free/Just like that bluebird/Now ain’t that just like me.

Blackstar begins by naming the Norse village of Ormen. In Norse mythology, the rainbow bridge that connects this world to that of the gods is Bifrost, which translates as tremulous way. Tremulous—as in trembling—as Bowie does so heart-wrenchingly as he backs into the armoire and out of this world.

When he heard the call, David Jones, who could walk the streets of Manhattan undetected, slipped over the rainbow and into his own imagination.

But with generosity and courage it seems he did not fully recognize, David Bowie spent his life pulling back the curtain on the Great Oz, showing the man, his frustration and fallibility, questioning art-making and then making it anyway.

I fear in the end he imagined himself “a very bad man but a very good wizard,” when in fact the opposite was true. The droves of people gathered at his front door and around the world may have found the masks fascinating, but only as much as the man, and heart, behind them.

I imagine catching David Jones wandering past shop windows plastered with red New Year monkeys, beneath golden, swaying lanterns. I would thank him for Ziggy Stardust, whose hair my mother copied and Scary Monsters, whose poster graced my eleven-year-old bedroom wall. I’d say thanks for Low and Hunky Dory, which got me through hard times. Thanks for The Man Who Fell to Earth and The Hunger, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke. Thanks for Diamond Dogs, Heroes, Lodger, Station to Station. Thanks for creating a soundtrack for my life and the lives of my favorite people.

Thanks for being a fierce, literate libertine, giving permission when I so badly needed it and inspiration always. Thanks, from the strange kids, for saying, No love, you’re not alone! You’re wonderful!

On the afternoon of January 10th, in what I later learned were the last hours of Bowie’s life, a double rainbow drew me from my desk and to the window. It arced across the skyline and ended at the Empire State Building, so strikingly that fire fighters in the station across the street took to the emergency dispatch microphone to exclaim to the neighborhood, “There’s a rainbow!”

As the first snow falls over Chinatown’s back alleys, I think: rainbowie!

There’s a Starman, over the rainbow, way up high, and he told me—let the children lose it, let the children use it, let all the children boogie.

Kim Wood's writing has appeared in Out Magazine, McSweeney’s, Tin House's Open Bar, and on National Public Radio. She has received grants from the Jerome Foundation and is a MacDowell Colony fellow. She is working on a book, Advice to Adventurous Girls, based upon the unpublished archive of a 1920s motorcycle daredevil. Her documentary film on this subject has screened internationally in festivals and museums including Sundance and the Guggenheim, where it double-billed with an episode of ChiPs.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something Happened on the Day He Died

Jordan A. Rothacker on David Bowie

On Friday, January 8th 2016, David Bowie turned sixty-nine and his final album Blackstar, was released. I purchased it that morning, having waited for months. On the following day I sat for a black star tattoo straight from the album cover; a recent writing project was lousy with black stars and I felt more than ever that Bowie and I were on the same wave. After a weekend of listening to the album I was awoken Monday morning, January 11th 2016 by my wife, “before you look at your phone, Bowie passed away yesterday.” She was right, my text messages were as full as my Facebook feed with tearful and shocked notifications from friends, but I was glad I heard it from her first.

It took until December of 2016 for me to finally read Simon Critchley’s little book, Bowie (OR Books/Counterpoint, 2016). I’ve wanted this book since it came out in 2014 and I remember reacting, “a book by one of my favorite living philosophers on one of my favorite living everythings? Yes, please.” Luckily I put it off until this 2016 re-issue with extra chapters treating Bowie’s death and final album. Although most of the book was written more than two years ago it is hard not to read the whole thing eulogistically. His spirit goes on though, now more than ever, as the last dreadful year has come to a close. I lost of close friends and faith in my country, but now my thoughts turn back to Bowie with hope his art can carry me forward.

What have I lost in Bowie? For the most part, the same things we all have: the chance for more music, more movie appearances, and just the knowledge that he is out there being brilliant and dashing, making art, and giving a wry smile to a paparazzo. What have I lost personally? True confession time. I have always dreamed of knowing Bowie (I’ve never even seen him perform live), but more so, and more embarrassingly, I’ve always wanted him to know me. I’d hoped one day he would read one of my books and like it. That moment of mutual respect between artists, that bump to my sense of worth from an artist who has helped shape my understanding of the world, art, and myself.

This is why sometimes Critchley’s book feels like it’s talking to me or for me. I haven’t read much about Bowie. He is mine and my feelings for him and about him need not be mediated. Critchley’s book however is now added to a small list of my favorite Bowie books which also includes Hugo Wilcken’s Low and Steve Erickson’s These Dreams of You.

Critchley’s book praises Wilcken’s so I’ll start there and circle around back. Wilcken’s Low (Continuum, 2010) doesn’t need a book review; it’s kinda perfect (I say kinda since perfect is such a strong word). It’s one of the best 33 1/3s I’ve read, and I’ve read a lot. I’m a sucker for this series of tiny books on albums of music as I have always suffered from that most Cartesian of obsessions in regards to my most beloved art works, the need to know how he, she, or they did it. The reverse engineering of a work gives me faith that maybe I could also do or make something comparable. Wilcken’s Low is like the sweetest of candies; I wanted to devour and savor all at once, which is difficult with such a short book. Wilcken chose Low because it was a definitive turning point in Bowie’s body of work and during maybe the most beloved period in the myth of the artist. In 136 pages the reader experiences a thorough historical context for the album and detailed production notes for each song as well as each song. The most important moments I savor from this book are descriptions of his work ethic and the well-researched information about his time in Berlin.

After a teenage obsession with Ziggy Stardust, the Berlin years have always been my favorite period and that’s where Erickson’s These Dreams of You (Europa Editions, 2012) comes in, illustrating the Berlin years in the subplot of a larger novel. The book is about a white novelist, Alexander “Zan” Nordhoc, and his family. The narrative opens with the election of Barack Obama not long after their adoption of a little Ethiopian girl with gray eyes named, Zema (mostly called, Sheba). The structure involves small paragraph vignettes familiar from Erickson’s last Europa novel, Zeroville, but otherwise from the start of my first read I wondered, “is Steve Erickson actually writing a domestic family novel? Where is the trademarked weirdness I love so much?” My worries were for naught, for after about fifty pages it started getting weird, and oh so wonderfully weird. Ultimately it is a novel about race in America and therefore about America itself. On the second page, watching the first black president’s victory, Zan wonders, “Do I have the right… as a middle-aged white man, to hold my face in my hands? and then thinks, No. And holds his face in his hands anyway, silently mortified that he might do something so trite as sob.”

It is the only book by a white guy that I included in my African Diaspora Literature course, and only in a summer section to follow complementarily Obama’s memoir, Dreams From My Father. The book captures the spirit of Obama’s election, his place in history, but never directly names him. This is Erickson’s way of writing historical fiction since Zeroville, never naming names. But what does this have to do with David Bowie? We can only assume that he is the “British extraterrestrial in a dress” or “the man who sings the hero song [with] red hair” whom four year old Sheba/Zema is obsessed with. These Dreams of You is a complicated work that shows all of Erickson’s narrative deftness, the twisting, ellipsing Mobius strip orchestration of strands and timelines that all interweave and make total sense by the end. One of those twists that proves essential to the whole follows a black woman named Jasmine, who while working in the music business is assigned to assist a rocker who seems a lot like David Bowie. She accompanies him and his friend Jim (Iggy Pop?) to Berlin where they record music with a man called The Professor (Brian Eno?). In his not so covert way, Erickson depicts the recording of the albums Low and “Heroes” and all of the escapades of that period: the lingering Crowley occultism, the conviction to kick cocaine through copious amounts of alcohol, the transvestite clubs, the obsession with kraut-rock like Can, Neu!, and Kraftwerk. Moreover, Erickson captures what drew Bowie to Berlin, what first enticed him through the writing of Christopher Isherwood. Berlin was not just the City of Ghosts, it was the City of the Wall, both East and West, Old World and New, Weimar burlesque and pulsing kraut-rock. It was a time and place that inspired Bowie to create two of his greatest albums (and eventually Lodger, which is still pretty good) that both helped take “pop” music to a whole new place, along with great solo work from Iggy Pop (The Idiot and Lust For Life, both produced and co-written with Bowie). In the almost caricatured portraits by Erickson are a stylized ideal of the artists at work, inspired by this liminal space, the guards posted on the Wall just outside the Hansa studio windows. It is a space where maybe the most emblematic theme in Bowie’s work comes out: love as defiance. “I can remember/Standing, by the wall/And the guns, shot above our heads/And we kissed, as though nothing could fall/And the shame, was on the other side/Oh, we can beat them, forever and ever/Then we could be heroes, just for one day,” as he says in the song “Heroes.”

But now, what does this have to do with a book about race in America? The Bowie character in the book tries to explain to Jasmine why he’s in Berlin and what this new work is all about. “Look, the whole century has been about black and white fucking… New York Jews like Gershwin, Kern, Arlen cumming southern Negro music while Duke Ellington ravishes Nineteenth Century Europeans like Debussy,” he says. Erickson’s use of “Bowie” gets at the heart of another central theme in Bowie’s oeuvre, the embracing and merging of binaries.

This is why I chose the book for my class and why I believe the students responded so well to it. The narrator explains, “Zan began pondering race when he was younger only because he began pondering his country, and knew that it wasn’t possible to understand his country without pondering slavery and it wasn’t possible to understand slavery without pondering race. He considered how his countrymen from Africa were the only ones who didn’t choose to be there; Africans were compelled to come and only once they were made to come did they choose to stay. Did that make them, then, the true owners of the country’s great idea, by virtue of having accepted the country in the face of so many reasons not to? If the country is more an idea than a place then are those who were so compelled its true occupants, given how the country’s promise to them was broken before it was offered?”. This is to support a conversation Zan has about race in America a little earlier where he says, “what the zealot or the ideologue really believes in is the zealous nature itself, the devout embrace of hard distinctions—the crusade against gray.”

As this book illustrates, grayness is what Bowie was all about. This AND that. Andro and gyne. Like how gray is both black and white, Bowie was masculine and feminine, straight and gay, artist and pop star (one could be critical and declare that all of this grayness is aspirational and point out that Bowie never escaped being a white, straight male whose aesthetic endeavors were all rooted in privilege and appropriation, but right now I am most certainly here to praise Caesar). Bowie helped destroy binaries by embracing them. His place in Erickson’s wonderful novel helps express this. If you think Erickson might be alone in this sentiment some tangential support might be found in the Acknowledgements of the 2016 novel, Underground Railroad, where Colson Whitehead says, “David Bowie is in every book [of mine].”

It is especially the last duality, Artist and Pop Star, which always excited me most about Bowie. He was legit and fun. Dissertation-worthy and danceable. He was the first side of Low and the second. He was references to Greta Garbo and the Golden Dawn all in one song. Maybe this is what makes David Bowie the quintessential Pop Star to many people. In Low, Wilcken explains how “popular music as it developed in the fifties and sixties turns the cultural paradigm on its head. With pop, postmodernism always came before modernism. Pop culture didn’t actually need any Andy Warhol to make it postmodern. Rock ‘n’ roll was never anything but a faked-up blues—something that the glam-era Bowie had understood perfectly,” and then quoting Brian Eno: “Some people say Bowie is all surface style and second-hand ideas, but that sounds like the definition of pop to me.”

This now brings me back to Critchley’s book in which early on he describes the “inauthenticity” of Bowie. “The ironic self-awareness of the artist and their audience can only be that of their inauthenticity, repeated at increasingly conscious levels.” Bowie clearly understands this as is evidenced in his song “Andy Warhol” off Hunky Dory (1971) in which we find the line, “Andy Warhol, silver screen/Can’t tell them apart at all.” On this topic Critchley continues, “Art’s filthy lesson is inauthenticity all the way down, a series of repetitions and reenactments: fakes that strip away the illusion of reality in which we live and confront us with the reality of illusion;” and, “Bowie’s genius allows us to break the superficial link that seems to connect authenticity to truth.” Finally, after more Heideggerian digressions, he brings it all home with: “In my humble opinion, authenticity is the curse of music from which we need to cure ourselves. Bowie can help. His art is a radically contrived and reflexively away confection of illusion whose fakery is not false, but at the service of a felt corporeal truth.”