Text

The Clowns Are In

A familiar assault on my senses occurs today, as I wait for electrolytes to reenter my bloodstream and undo the massacre that all of those glasses of wine brought. It may be a bizarre type of wisdom that has me repeating history every December 31st, as though I believed there was something new to be found in the umpteenth time I drove a nail through my palm.

What sort of logic is this engagement with the ever-spinning wheel of return which has me dipping into waters so tainted, not just with the poison of intoxication and withdrawal, but with the certain knowledge of self-defeat?

In short, why does it seem that I choose to complicate my ability to see the world as it is, horrors and all, by filtering my experience of this life through various flows between pleasure and pain?

Perhaps there is some value in my refusal to learn. Perhaps in this refusal I am merely addressing the sham modality of neoliberalized values dictating that life must be seen linearly, that goals must be set, that accomplishments are ratcheted according to the efforts of some triumphant will and not the vagaries of impersonal systems over which few of us have any say whatsoever.

Perhaps, through the influx of chemicals on New Year’s Eve, I am making some pathetic statement of my unwillingness to consent to a life that seems always to set its sights on what lies ahead, to enact a ban on repetition, to see in every return to a previously encountered condition evidence of one’s unfitness in the marketplace of success.

I hereby endrunken myself, yet again. An impotent, though, nonetheless, unconditional, declaration of resistance to the demands of the modern world.

If it is true that, in the fourth year of each decade, the particular traits and sensibilities of that decade are visibly codified—so that we finally see what the ‘80s were only in 1984, the ‘90s in 1994, and so on—then we may expect 2024 to finally inscribe on the public conscience the particular breed of casual horror and clownish absurdity that has been afoot for some time now. We wouldn’t be foolish, either, if we also saw in the unfolding of this year clear signs of the nature of this entire century, being as we are now almost a quarter way through it.

In the same way we see conclusions of 19th Century orders and signs of 20th Century innovations in the first World War, the Russian Revolution, and jazz, so we might see in 9/11, the Great Recession, Trump, Covid and Taylor Swift all of the needed bits of DNA with which to encode what will ultimately be the 21st Century project.

What do these developments say about what we might expect, not just from these ‘20s we’re almost halfway through, but from this century we are now almost a quarter of the way through?

What comes to mind at the moment is the creeping sense that expectations must be thrown out the window, that the promises that have been made will not be kept, that the righteousness of our previous beliefs are now in the harshest light, that there can be nothing else but folly in believing in the assuredness of the way forward.

The big deals of the 21st Century so far do not paint an encouraging picture for those of us wanting to see a portrait without antinomy, a landscape without contradiction. Living with the vertiginous, as though every step were on a tightrope, must be accepted. Incorporating the assault on the senses—knowing that the images that surround us have been reified to such an extent felt reality itself has lost its grip on hegemony—will become the skillset of those who survive.

How to constantly grapple with clammy palms and the erroneous math of the techno-future of the present day, how to stay awake while sustaining bludgeoning usurpations of common sense, common decency, common experiences and common values, these will be our tasks. Maybe I’m being pessimistic if I think that few of us are up for this task. After all, it is an inhuman world.

It might be said there’s nothing new in this, that every new century underway greets the living with just such destroyers of their most basic suppositions. Maybe, by the year 2075, it will seem that we had nothing to worry about at all, that the perceived instability of the early part was merely the usual scrambling of familiar logics that occurs each time a burgeoning set of one hundred years ticks along.

I suppose we shall have to wait and see.

But, as I continue to ponder the metaphysics of my drunkenness, as I seek to commit a spiritual suicide, a self-immolation in every sip, if only to cast my ballot of resistance to this demonic enforcement, this Boschian grotesquerie of modern life, this imagistic chaos surrounding every single element of our experience, I will not suppose that the ludicrousness of this century so far is some artifact of perception. I must believe in epistemic transparency. What I sense must not be so far off.

Therefore, I must greet each new year with the same suspicion, with the same eager encounter with repetition, with the ugly feeling that the labyrinth will always bring me back to square one. I must disabuse myself of the strictures of the forward moving path, of the certainty of the way, of what lies ahead. If we can not escape the matrix of modern absurdity, we can at least know we are in it, never allow ourselves to be duped into thinking otherwise.

If there can be a resolution, in a world that has abolished resolutions, let it be this: may I return to the original kernel of what is now termed “wokeness”; may I “stay woke” to the emergence of this plenary outfit of constant yammering and solicitude, may I know, at every second, how my data, not just my online behavior, but the data of my soul, is being robbed.

I shall drink to that!

Happy New Year

1 note

·

View note

Text

Access and Activation

I am prone to a kind of reflexive lunging for the blade in the haystack, the blade of stridency and political agitation which, during “normal” times, is kept hidden under needles of hay and which, during times of crisis, is fidgeted over with nervous hands parsing hay needles in order to get to the handle.

I like to bring the hatchet down. It’s in my nature. It always feels like the most correct course of action.

I am susceptible to the defensive posturing that happens during war, the hunched shoulders and darting eyes of those who have grown up with bombs.

However, I wasn’t the one who heard those bombs. That was my father.

I’ve written about how war, specifically the experience of World War Two on the part of my father, informs my perspective, how the imprint of war shapes my attitude and my behavior. It comes in the form of a generational trauma that lives on within me.

You experience this type of trauma not because of what was done to you but because of what was done to your parents and grandparents, a type of trauma that is passed down to you like a genetic flaw or disease.

But these aren’t the only contributors to the trauma of my father’s upbringing in mid-century Germany, the effects of his experience of war and bombs which he passed onto me.

The effects of the kind of society he grew up in, a white supremacist totalitarian society, factor into the unease I experience within me and mingle with the agitation brought about by the sounds and tremors of munitions and explosions.

With every knee-jerk reaction I experience when activated for combat, whether that combat be intellectual or physical, there is also the ugly inheritance of vague ideas about racial fitness.

It lives and breathes in my blood, as if there were all these radioactive amoebas swimming around and each one had a tiny mouth singing out one part of an overall harmony, a dreadful chorus about lineage and nations and unity of blood.

During such moments my yearning for access to deeper stories than these nativist ones soars very high, even as it is thwarted by the activation of these little sleeper cells of trauma and racial animus inside my body.

What always motivates my liberalism is the total rejection of these voices of ethnonationalism.

I grew up hearing horrid language about so-called racial realities and their determinative valences, that this can and should be understood politically, that one must organize in society according to skin color and that one must understand that the lighter the color the more deserving of justice.

I have a direct, eyewitness account of these sentiments, for I heard them every day growing up in my home.

When I see what is happening in the Middle East today, there is a direct recognition of the sparks of racial hatred.

The element of religion is present as well, for my father also tried to teach me that Christianity was superior to other religions, not because of some supposed scriptural connection to the real truth, but because it was a historical, organizing principle, a political force, around which the glories of Christendom and Europe have brought civilization, through empire and capitalism, to the entire world.

When something happens, like the horrifying escalation that occurred on October 7th, I run to the haystack and grab the blade and hold it up to the sun. I know how I will use it: it will be in defense of my beliefs, the principles I adhere to which stand in the starkest contradiction to all of those terrible lessons my father tried to teach me.

And still, the insufficiency of stopping there becomes apparent. For to many, the side which I must pick as a result of these stated beliefs is on the side of the IDF and on the side of the nation whose people we in the West must support.

But I can’t bring myself to pick that side.

Because of my politics, I can’t help but see imperialism on “that side of the fence,” and I have rejected imperialism in every form in which I see it.

What is my role, then?

I keep asking myself. There is a part of me that knows how direct my lineage is to the gas chambers. I have already written about my grandfather’s support of the Nazi regime.

How do I support Israelis without supporting their government? How do I support their right of self-determination without removing my support for the same right to the Palestinians? How do I express solidarity with Jews while also expressing solidarity with Muslims?

I’m not talking about politics. It is not enough to simply say that, in fact, many, many Jews are now protesting Israel’s actions and their presence on my “side of the fence,” on the side that is calling for a ceasefire, means I can now worry a little bit less about the need to have solidarity with all Jews.

It’s not enough to pick one political side of the Jewry and think you are advocating for all of the Jewry.

Germany does not select to which type of Jew its post-war policies towards Jews, its reparations regime, is directed. If you are Jewish, it doesn’t, nor should it, matter what political beliefs you have in order to qualify for the benefits.

This means that this policy is extra-political. And rightly so. And, as a descendant of a Nazi, I feel a very powerful desire to apply this same policy in my own personal advocacy, irrespective of how my politics will naturally bring me into conflict with it.

There is a part of me that demands solidarity with all of the descendants of the victims of the crimes of my ancestors. I feel a large responsibility towards all Jews, including those Jews whose politics I find abhorrent.

There seems to be an irrefutable logic to that demand. For how can I turn my back on the national project of the very people whose existence my own people tried to exterminate?

How can I ignore the need on my own part to continue to hold the torch out in their defense? this especially given how my father never demonstrated to me the slightest appreciation for the severity of Germany’s war crimes?

The editors at Tablet Magazine, staunch sympathetic voices for the actions of the Israeli government, had graciously given me a spot on their platform this past June to carry out some of this type of reckoning with my own lineage.

The magazine is a writer’s paradise. Every word is written with care and intelligence and probity. It’s an honor to be a contributor.

Yet, I knew what the politics of the magazine were when I wrote the piece for them. And now I wonder whether, if the piece were being written today, after October 7th, I wouldn’t try to find another outlet to publish it. I also wonder, assuming they’d be aware of my politics, if the keenness of the political clash between my beliefs and theirs wouldn’t make it difficult for them to give me the platform they did earlier in June.

When I think of this it seems clear to me that, while there is no limit to that historical defense of a people which issues from the demand coming from recognition of the crimes of my ancestors, there in fact is a limit to my defense of the actions of the Israeli government.

I will forever defend the legitimacy of the Israeli state, even as I denounce with every fiber of my being its government’s modern behavior.

There are many who don’t believe that such a division is theoretically possible, or even morally permissible. There are many who say that defense of Israel is defense of Israeli policy towards the Palestinians and that you can’t have one without the other.

I humbly and respectfully disagree.

This piece, I found, did a fantastic job of analyzing, from a more linguistic standpoint, the difficulty of the public conversation at present.

I believe Israel is committing crimes which I can never bring myself to support. I tell myself—until I’m blue in the face—that my socialist politics make me see this conflict as an imperial one and therefore demand I reject wholeheartedly what Israel is doing.

But I will always feel like I’m betraying a cause when I do that, that there is a historical mandate placed on me which I am now turning my back on.

And yet, the other side is stronger. My politics are my politics. My politics are the result of some of my deepest beliefs about humanity in general. It seems as though there’s nothing to be done about that.

I continue to remain open to evolution. There are many beliefs I once had that I no longer hold onto.

But my politics, my core beliefs, my principles, must come before other responsibilities. Considering that my feeling about those responsibilities is situated within a highly personal legacy that dates back several generations, and is therefore issuing from a consensus that has long since passed, I think it’s reasonable that I nonetheless prioritize my political beliefs today, the absolute importance of remembering my connection to my ancestry, with all of its horrors, notwithstanding.

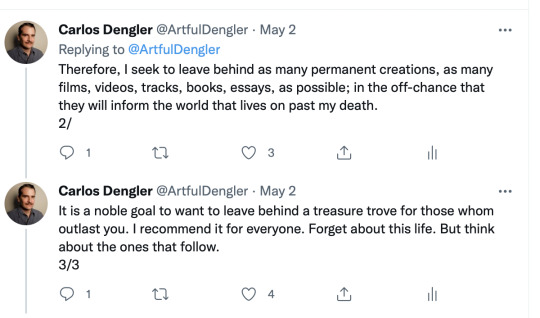

I wish I could speak in the way I am speaking now, only on Twitter. Unfortunately, that isn’t the venue for this kind of inquiry. Nonetheless, I feel compelled to use Twitter to express my political beliefs, with all of the two-dimensionality that limits such expression on that site. But it doesn’t exactly make me feel whole or good.

The task of putting the blade down, of threading the needle now, the task of finding access to the third way—in what appears to be a hopelessly, insoluble binary and zero sum conflict and crisis—seems more than ever out of reach.

It is very sad.

. . . . . .

I remember how utterly baffled I was by the 9/11 attacks.

Who hates us so much that they would be willing to do this and why? On top of all of the feelings of fear and anger, I was also very confused. I couldn’t understand what we had done that would make us such a target.

There wasn’t yet social media, but there was a brief precursor to the way social media circulates information in an informal way. They were called chain emails.

I remember scrolling through endless reply brackets of discourse on email, many of it humorous, much of it the stuff of urban legend. These emails were getting copied and resent many times over and their origin was often too distant to be able to detect, but the stories were by turns amusing, alarming, entertaining and serious, nonetheless; much like a lower powered version of the outrage hunting and doom scrolling that happens every day on Twitter.

After 9/11, I recall reading a quote from an interview with a prominent rabbi who said that, as a result of the attacks, we had entered the 21st Century through a ring of fire, and that we must now understand more than ever that we are all connected, that what we believe and what we support and what we advocate for has ripple effects throughout the world, that our policies have serious impacts on people with whom we share very little culturally, but who are human beings nonetheless, and to whose humanity we are in many ways responsible.

I’ll never forget it.

It was the first time that I understood how to approach the specter of political violence, how simply categorizing something as terrorism and stopping there is always insufficient. It put the 9/11 attacks for me in a completely different context. I wasn’t confused any longer.

I watched the second tower fall from the vantage point of my East Village rooftop. Around me I heard the simultaneous cries of horror from all the others on rooftops all around me. I remember the fear I felt of being invaded, this newfound fear of being attacked. I remember the strange, blunt patriotism I never thought I would ever feel that came as a result.

But amidst my fear and anger, I was still very confused. Until I wasn't.

It was with those wise words which I read in the email chain that I understood there is a very great difference between “blaming the victim” and something more nuanced, the understanding that if everything is connected, then what I do affects others throughout the world, through ripple effects.

That was when I realized that critique of empire would be one of my chief political preoccupations for the rest of my days. Because the American Empire was on its last legs, though none of us knew it. But I knew that all of this business about War on Terror was a sham. I knew it was a sham because there was no space in it for understanding our role in the 9/11 attacks.

I realized when I read that email chain that there was nothing wrong with admitting that the privileges of being an American, because of empire, come at the cost of other people in far off places. And at some point in time, the bill will need to be paid.

That doesn't mean that it was "America's fault" that it got attacked. It just means that America plays a role in the conditions that brought about the attack.

It’s almost impossible not to take a side these days. If I am unsuccessful in being neutral—and that is almost always the case—it is because I have to be honest with myself about my own political beliefs, which are very strong.

But I still have to ask why I have those beliefs. I have to ask what brought me here to this point holding the blade aloft.

Interestingly, I can see this blade is not only mine. It has bloodstains on it from previous eras. It’s been used before many times, by combatants on opposite sides of the fence, for this cause or for that cause.

The blood of the opponents in all of those matches commingles eerily on the shaft of the blade. I’ll never know whose blood belonged to whom. In death, the blood of one’s enemies merges with one’s own.

Perhaps I should just do everything in my power to simply hold this blade towards the cause my heart finally tells me to point it towards.

But never use it. Never thrust the blade.

Maybe that’s the best I can do. Maybe such incomplete and unsatisfying conclusions are the only realistic position for me to hold at this time.

But I will keep my eyes open and my ears alert. There’s still more to learn.

Peace to all humans.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Farewell?

Hi Carlos!

What a pleasure Private Earth! Really. I am not a professional in the music industry, so my opinion is just the result of my emotions.

The whole album is gentle and at times joyful! Desert Flora is addictive (okay, pass me the term please, but it's almost a shamanic trance, I love getting carried away by the rhythmic component!). I love then, how Rising Mountain is such a sunny, positive, and fresh release.

But there is one moment in the entire album that has continued to speak to me, for hours, like an echo.

And I can even tell you exactly when it is. Everything begins with a dialogue between the different instruments; a dialogue made up of "words," silences, pauses, exchanges. Then, minute 7:27… it's like a hug, a moment that I would call indulgent and poetic. It's on Ancient Lake.

One last thing: I . . . read your new personal essay "A Farewell to Armbands".

It's really touching.

I don’t deny that I felt a certain contrast between the sweetness of Private Earth, which I had just listened to, and the (at times) raw words of what I had read. The healing power of music.

Yours,

Someone Sweet

———- ———- ———- ———-

Dear Someone Sweet,

I am so happy to hear that Moment 727—shall we call it that?—has found its way to your heart.

When I was composing “Ancient Lake” at the piano I went very slowly during that section. I was very inspired by Deuter, specifically his Atmospheres, an enchanting and resonant album of delicate piano and synth string arrangements. What I love about this album is its ability to conjure rich landscapes very minimally, with almost no movement. Much of the melodic material is childlike in its innocence, sometimes seeming like the simplistic lines of a lullaby. I half expect to hear the chimes of an infant’s mobile. It’s one of the album’s charms.

And Atmospheres was in the forefront of my consciousness as I labored over the chord progression beginning at Moment 727 in “Ancient Lake.” I wanted to emulate that sense of stillness, plainness, delicacy and innocence that Deuter is so good at, something so frail and delicate as to conjure the sound of the exhalation of seraphim. That this moment, Moment 727, came to you as an embrace makes me very happy: I wanted this section to be like the most ethereal caress imaginable.

Let’s face it: New Age music is limited. I say this not to criticize the genre, nor to make any special case, as I believe every music is limited, one way or another. But not every music is limited in the same way. Heavy metal, for example, is limited by its volume, intensity and cultural values: its affective disposition as an extreme engagement makes it unsuitable for a great many other avenues in life and forms of expression.

New Age has similar degrees of limitation, though manifested completely differently. It is a deeply stigmatized genre, for good and bad reasons, but one of the bad ones is for its purported simplistic musical value. It is true that musical innovation or even, I’ll grant you, sophistication, is inherently at odds with the core composition of this genre’s musical structure in general. But this is a disingenuous critique: a Hallmark card is not any less beautiful of an object for its lack of aesthetic sophistication when it is opened by the person to whom it is addressed: at that moment, fulfilling its use-value, which is to make the receiver happy, the card is one of the most beautiful things in the world. At such moments, we would not necessarily want to be greeted with the ingenious paintings of, say, a Matisse.

So, yes, its limitations are profound, though, crucially, far from disqualifying. I regard as unfortunate that its disgrace as a genre of music persists to this day, so much so that a great many contemporary New Age artists must perform ridiculous contortions in order to avoid the label. That is very sad to me.

Not all music need stand on its own. “Mere" practicality is not inherently disqualifying. So what if a music’s raison d’être is solely, as in the case of dance music, to move the feet? Then, what if it’s “merely” to calm the soul, as it is in New Age? These practical uses for music have monumental amounts of cultural value and should never contribute to a lowering of status in our eyes.

During our most vulnerable moments, or during moments when we are so overwhelmed we can barely tolerate the sound of a car passing by us, only a certain tenor of frequency may arrive at our ears in such a way as to support this delicate state, and not disrupt it. It is not a particularly interesting tenor, nor a particularly sophisticated one. But that precise tenor is nonetheless one of the only ones that will do for those moments.

Sometimes we can only hear bells, and nothing else.

Sometimes we can only hear a lone flute, and nothing else.

Sometimes our insides feel so riven with anguish and uncertainty, sometimes we are so frail, that only the simplistic sounds of this genre are tolerable.

Sometimes we are like a chick in a nest: a mere gust of wind and it’s over for us. Sometimes those rather sophisticated and interesting phrasings of a luminary of music, like Jimi Hendrix or Frank Sinatra, have too much sophistication, too much interest and too much personality for us to be able to tolerate, and those artists’ exertions become so many threatening gusts of wind tossing us out of our frail nests.

I’d venture to say that we still need a naive and jejune music such as New Age for those moments. And, as I can tell you from the relatively limited experience I have with this genre of music, it is a deceptively difficult task for music to accomplish. It is incredibly difficult to restrain oneself from being “too interesting.” Creating music that recedes to the background, but nonetheless engages with the soul, is very complicated and I am still learning more about it every day. May New Age continue to offer the solace it is designed for and which it accomplishes so well.

Perhaps by now, Someone Sweet, having read my eulogy for New Age music, you understand a little bit better this contrast which you pointed out happening between my recently published essay and my recently published album. Sometimes I wonder if I am not fashioning some sort of safe space for my soul in dedicating myself as much as I have to New Age music, given that, in my writing, I am focussed on a type of engagement that is far from the merely practical.

The writing that I am most interested in reading, and the kind I am most interested in pursuing as a craft, seeks to lock horns with a rather aggressive steed, the parts of the unconscious, both within oneself and within the larger sphere of human relations, which are hellbent on remaining unseen and unheard and will put up the bloodiest, most hostile resistance to having their truth announced to the world.

“A Farewell to Armbands” was the Somme, a titanic confrontation with the enemy in this ongoing war between the light of the self and the darkness of the unconscious. Not every one of my essays is, nor will be, so cataclysmic as this one was, but each one still has an element of that wrestling match with the dark. And there may yet be more Sommes in my future. That is what writing is for for me.

My favorite kind of writing is the kind that acts exactly as I ascribed to camp as a form of expression in the piece itself, as a kind of “hot lamp” that “cauterizes” wounds. Make no mistake, this is a dramatic and violent undertaking. And so, when we come back from this fight—a fight I would like to help as many people fight as I possibly can—we will also need to be soothed, to put the final gauze and the final unguent on the gaping wound. For me, that is not writing, where the battle takes place, but music, which should perform the necessary function of field medic. If you’ve been wounded in battle, maybe even lost a limb, you need morphine.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heavy Metal is Not Your Mascot

The modern recast of heavy metal as salubrious societal analgesic comes at the price of its originally subversive appeal.

This video came across my algorithmically determined online television viewing streaming platform—otherwise known as YouTube—earlier this afternoon and watching it made me think some more about a topic I’ve been meditating on now for a long time:

youtube

As someone who grew up in the 80s and 90s listening to heavy metal, who is now an adult living well into the 21st Century, I’ve often found the ongoing evolution of the public perception of this most idiosyncratic music genre rather puzzling.

You see, I actually remember when the now laughable moral panic around heavy metal was in full swing, when the news show 2020 aired an episode about Ozzy eating a bat, about Judas Priest supposedly causing a couple of kids to shoot each other in the face and about Mötley Crüe being Satan worshippers because they put a pentagram on the cover of their second album.

I mean, anyone who was born after 1990 has got to look back at that saga and see something truly surreal. How is it that such caricatures were so compelling, so effective in scaring the well-to-do, those bourgeois patriarchs and matriarchs who today, in the age of Internet pornography and 5,678,987 television shows, are way too inundated with imagery to really be scandalized by these bespandexed dudes with long tongues? At least the McCarthy Hearings can be seen as a national security concern and therefore seem somewhat believable that it occurred, so long as you consider the country had only recently come out of a world war and its principle ally had now become a world power with a diametrically opposed economic system.

But some mumbly long haired white dude who chopped off the head of a bat in his mouth?

If a dude in America bit off the head of a bat the way Ozzy did decades ago, he’d be commandeered by the feds for gain of function research (drumroll cymbal crash I’m here all week, folks), not become the subject of a scandal. Actually a dude who chops off the head of a bat with his teeth would today more likely have a reality show than become the subject of Senate Hearings. In fact, eventually, that dude did have a reality show (more on that soon).

But the truth is that heavy metal did in fact scandalize. The satanic imagery and long hair festooning the average metal album back in the 80s, funny as it may seem to modern sensibilities, did actually have the power to shock, no matter the quaintness of the moral panic by today’s standards. For myself growing up as a teenager in the late 80s, the sight of a grown man with a big mane, an electric guitar and a leather jacket signified an authentically antiauthoritarian pose and an effective political tool that communicated independence and freethinking. But the only way that it was actually able to signify all of that relied on its counterdependent effect on pearl-clutching conservative adults. Without the ability to scandalize, disturb and deregulate the affect of the authoritarian class, we teenage underlings had no power. If we couldn’t scare anyone, it’d be like a milquetoast haunted house, not anything to worry about and therefore not worthy of notice.

But this ability to serve as the bugbear for conformist interests could also acquire a specifically dialectical manifestation. You didn’t just have to turn it up to eleven to get people’s attention, you could also speak your mind, something that some of the more articulate members of the “movement,” if we can even call it that, like Dave Mustaine and Alice Cooper, made a habit of doing during interviews. I have a vivid recollection of being moved out of my seat in 1985 at the sight of Dee Snider, curly mop swinging from his head, entering the committee hearings that Tipper Gore put on for the purpose of those warning labels that are now ubiquitous on extreme music catalogs, mostly on hip-hop records (perhaps an early version of the now common trigger warning). He entered a room full of suits and politicians and on national television read aloud his prepared notes, decrying censorship and governmental overreach. In the following interview conducted by the committee—which, funnily enough, included Al Gore—Snider was charming, funny and intelligent, totally comfortable in front of DC legislators and, more importantly, persuasive in his defense of the moral imperative of his way of life.

The importance of that particular moment for me is difficult to overstate. More so than even the weekly diet of videos on Headbanger’s Ball every Saturday night, the event of Twisted Sister’s frontman speaking truth to power on network television transformed my sense of what it meant to stand up for personal autonomy. Something about the juxtaposition of an articulate voice with a rebellious mien, like a Hell’s Angel with a PhD, floored me and shook me deeply: it made me believe in the necessity for heavy metal to be undergirded by an ideology, one that needed to be clearly defended using the lexicon of the “oppressor” against the oppressor and deployed by a member of the tribe. From that point forward heavy metal was for me a political device, not just a fantastic type of music, but a rhetorical quiver in a bow, a language and style comprising a disruptive affect designed to incense the neighbors.

And it worked. After I grew my hair, stuck some pins on my denim jacket and ripped my jeans, I started having the impact I so desired. I made all the adults around me angry. All the teachers hated me. Every single grown person’s eye looked at me askance and clutched their children when they saw me walking down the block. And the reason why this all worked was because, back then, before our pop culture became recycled and regurgitated and remixed and mashed up over and over again, before the Internet made every new thing only yet another layer on a cultural palimpsest, heavy metal still had the ability to shock. There still were pockets in every suburb of every state suffused in middle class propriety with nary a flower pointing in the off direction, a purist fantasy more than easily defiled by the angry decibels of a car stereo blasting Iron Maiden.

But what happens when this all changes? What happens when the Pope of Evil himself, the chiropteran eater, the Pablo Escobar of the offense cartel, one Ozzy Osbourne, reinvents himself as a lovable, hapless, perfectly innocent pater familias within that most innovative medium known as the reality show? What does it say about the political device of heavy metal when its chief icon, who for a whole decade was seen as the black void of all morality, becomes normalized, through one of the most commercial mediums in television, as merely another version of modernity’s companionate figure, the flawed-but-well-meaning father?

I think what happens is what’s in that video I started off this post talking about. What happens is the evolution of a once disruptive force into a kind of medicinal compost, a panacea for the legions of stressed subjects littering the manifold of capitalist relations in the new millennium, a political device turned into a therapeutic regimen. In the world of this video, where psychologists may opine with straight faces about the salubrious properties of heavy metal music, Ozzy Osbourne is no longer the archetype of evil he once truly represented, but an avuncular wizard with John Lennon spectacles, promising peace and harmony, all while—quietly—socially reproducing the specter of the beloved nuclear family.

You might say that heavy metal is an example of that over-referenced business phenomenon, that is, the proverbial “victim of its own success.” It so captivated a whole generation of people, mostly Gen Xers, who’re by now all grown up, that these people have successfully, through shows like Stranger Things, influenced the subsequent generations’ curiosity for analog culture and managed to keep metal alive as a hotbed of durable cultural properties, though with the necessary consequence of deracinating it from any of its originally subversive potential.

It’s true that authentically subversive metal continues to live on in the diaspora of micro-niche territories for which YouTube, SoundCloud and Spotify serve as the main platforms. Metal lives on, chiefly in the form of an extremely diversified field of thousands of new artists, many of whom have serious artistry and talent.

The video above is in fact accurate: metal doesn’t so much as shock or disrupt as it catalyzes self-improvement through extreme ritual. There’s a very strong case to be made for the spiritual benefits that extreme imagery have on society. In Hinduism, the displays of icons of evil gods in front of one’s homes is encouraged, something poet Robert Bly calls “embracing the Shadow.” By this reading, an embrace of the lifestyles and rituals in heavy metal fandom constitutes a successful invitation of the darker energies inhabiting all spheres of human experience and which we ignore at our own peril.

But the real sting is gone. The heavy metal of my adolescence was not a normalized construct which could be favorably documented for its restorative and spiritual potential. It was a terrifying and disruptive weapon that’d been placed in the hands of youths who were in desperate need to announce their personal autonomy. In my own case this took on the aspect of a need to set expectations around the adults in my life. I was to be understood not as a normal kid but as a self-described hellion and my manner of dress and musical taste reflected this desire to offend and frighten for the purpose of stating my preferred manner of being treated by adults, as someone who would not follow their prescriptions, values and career recommendations.

Maybe I’m just falling victim to the natural tendency for older folks to chafe at the loss of their beloved value environments. “These kids,” and so forth. I will say that if you haven’t yet, please read Freddie DeBoer’s essay on the 90s because it makes a very strong case for why this might not actually be the case. It is true that the innocence of several decades ago looks positively embarrassing by today’s standards, especially when coupled with the decadence and optimism of new media in the 1980s (see “Looks that Kill”). Furthermore, the notion of heavy metal as an authentic political device is severely problematized by the hegemonic impact of its mostly white, male and, way too frequently, nativist, affect. It can be said that the primary maxim in heavy metal of the freedom to flout the rules is merely a reproduction of a Eurocentric, masculinized “freedom” to thrive in the patriarchal caste system it relies on for its special privileges (see Disco Demolition Night). Kaleefa Sanneh has written compellingly about how the rockist critical analysis that dominated music criticism for so long is another reproduction of this narrative (click here for my review of his book Major Labels). Interestingly, this problematization itself also needs further problematization through a class lens, as heavy metal has hardly been hegemonic in its role of providing a soundtrack for working class solidarity (it’s true that, in the overwhelming majority of cases, we’re talking about a white working class solidarity, but let’s save that conversation for another post).

The idea that the public perception of heavy metal has been degraded from its originally revolutionary aspect relies on a certain element of the status quo that, since that time long ago, has greatly shifted. Cultural historian John Higgs has written powerfully about the exact nature of this shift, what he characterizes as an increase in emotional intelligence on the part of Gen Z. Read this piece he wrote about his experience watching one of the most beloved Gen X cultural properties, one that is situated perfectly with the zeitgeist of heavy metal’s classic 80s period, The Breakfast Club. To Higgs, having watched the film with a bunch of Gen Z kids led him to believe that this film, whose Bender protagonist so represented the deepest aspirations of nonconformists like myself, “no longer makes sense at all to modern teenagers.” It’s difficult to disagree with his analysis. Please do yourself a favor and read it (it’s short).

The meaningful difference between the two eras being discussed here, the era of my adolescence and the era of the microdoc YouTube video I posted above, lies in the fact that adults are no longer being treated suspiciously by adolescents. This makes perfect sense when you consider that those of us who grew up during the 80s were experiencing a transitional period in between a paternal model of development and our modern companionate model. Heavy metal music was a perfect vehicle to defy the paternalistic encroachment of the adults who were still stuck in a pre-Elvis era of puritanical conformity. This isn’t the time or place to fully flesh out what I believe might be troubling about some aspects of the companionate model. But I think it’s beyond doubt that, in sheer terms of critical awareness and empathic response, Gen Z are miles ahead of Gen X, and that is something to take note of, especially for what it says about family relations. Interestingly, this advent has done little to stay the epidemic of mental illness among this cohort, though the causes and correlations of that are likely found in different arenas than in the family (ahem, Instagram, ahem).

I will admit that it’s pretty clear that the revolutionary affect of the heavy metal of my teenage years appears more like a counterrevolutionary force in the present day. For a truly revolutionary art, punk music is a far more effective entity than heavy metal. Perhaps it was heavy metal’s more central provenance within the historical line of rock music that I found so persuasive back then. Unlike the zine pamphleteering and Xerox iconography of social unrest directly visible in punk music’s propaganda, heavy metal made a more mainstream case: it was a broader movement than anything punk could hope to muster. It’s interesting to consider that punk was popular only in its more tepid incarnations in college rock and Grunge while heavy metal could attain wide popularity with relatively less devaluation of its subversive content.

But it’s this more broad appeal that also complicates the picture of a heavy metal music as a truly revolutionary force.

At the same time, it’s hard for me to take seriously the idea that heavy metal today is to be lauded for its spirituality and therapeutic effects. The zeitgeist might have shifted to better, more humanistic environs. But heavy metal should not be regarded as the feisty commercialist mascot to a self-help movement.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Very First Colonoscopy

It’s definitely an aging milestone when your doctor tells you it’s time for a colonoscopy.

Recently, though, it may be less so. The AMA made an adjustment to its advisory statements on when to begin doing this procedure—they changed it to, I think, 45, from 50—and it’s a noteworthy indication that, perhaps, having a colonoscopy is not the same type of seniority signal it long has been.

Still, it’s cold comfort: there’s no way to lubricate it, when you hear the dreaded “C word” while you’re buttoning up your shirt and your doc’s typing into your file, it really means a very painful thing—you’re old.

But that wasn’t the whole of it. The news of the necessity for a colonoscopy, along with the increasing sense of my impending doom, came with an added twist: I’ve never gone under in my entire life and this procedure is not feasible without giving into a hit of propofol.

To give the reader a sense of the extent of my trepidation: when I was a teenager and had to get my wisdom teeth taken out, I opted for local anesthesia. The idea of choosing to lose consciousness was so horrifying to me that the disturbing crunch of pliers and saws on my molars, as though my mouth had turned into an active quarry, though a blood-dripping one, was deemed a less unpleasant experience than going into the deep end, losing consciousness and turning off the lights, even if only temporarily.

I know this has to do with loss of control, of course, how could it not. The act of submission to the gas is an irreducible act of trust. In essence, you are choosing to kill yourself and turn yourself into an inert mass which a bunch of specialists can then have their way with. You are trusting that these specialists will then wave some magic wand and resurrect your inanimate body from the dead, after which you somehow rise again to walk among the living.

So here it was, a moment I’d long deferred in my life, one which I’d been fortunate enough not to have needed to undergo because of anything more serious than a simple routine check for prostate cancer. I booked the date, postponed it a couple of times out of fear, and finally gave in and went to the hospital on the appointed date.

It was Colonoscopy Day at the doctor’s office and there were people coming in and out. And all of them, every single one, because they had submitted to the gas, were suicides magically restored to life. How was it possible that so much death and subsequent resurrection could occur in the span of only two hours? What kind of factory of death and reanimation was this place? My instinct told me that this event was way too major to be something that could happen at such scale. Aren’t there priests involved? Aren’t there lengthy and therefore costly rituals that must accompany these acts of suicide and sacrifice?

When my turn came and I was waiting to be ushered to the operating room after changing into scrubs, I saw the person who was ahead of me in the waiting room, a woman of probably sixty or so years, only moments before a fully ambulatory, sentient being, now dead and lifeless on a gurney being wheeled out of a room. In moments, I thought, that was going to be me. In moments, I contemplated, I will be reduced to mere matter, a pudgy assembly of tissues and bone that can be twisted about at will like a less-flexible Gumby. What horror is this life that it may include such awkward moments when some of us actually choose to become the Play-Doh of other beings.

I told the nurse how frightened I was and I think she misunderstood me because she gave me a speech about how we all fart and there’s nothing to be embarrassed about. I didn’t have the energy to clarify. I was too anxious to think straight enough to tell her that I’m not embarrassed about what my body does but that I’m terrified that in a couple minutes I will be nothing but a body. But I took solace in the care and attention and sympathy she showed me and was grateful that her newly sacerdotal function was motioning me gently over to the other side. The air in the room had the tenor of the electric chair and last meals.

When the doctor came in he noticed that I’d brought the book I was reading into the operating room with me, something not all that common. I had thought that perhaps if I were distracting myself with my reading while the gas was introduced that I’d be spared the terror of knowing I was about to die. He inspected the cover and took note of the title: The Cultural Roots of National Socialism. I was reading this book as a primer for an essay I was writing about the German side of my family who were up and about in Bavaria during World War II. This book, long out of print, is a fascinating collection of the historical paraphernalia in Germany that, when all put together, paint an ominous picture of the state of the public German consciousness before the arrival of Hitler. In particular, it is an unsparing condemnation of the petit-bourgeois of Germany, whose middling cultural understanding and brutish jingoism and cruel antisemitism all but paved the way for the Nazis to take over.

I’m uncertain the doctor was able to glean all that from the title, though. He seemed puzzled by having to confront the words “National Socialism” just before administering a routine rectal probe.

Nonetheless, the book saved me, though not in the way I had originally intended. Being the chider, the doctor asked me to spell Mussolini backwards. I was too nervous to even get to the “L” and so he said, “Let me make it easier: spell ‘Czechoslovakia’ backwards, will you?” The gas was introduced (really it was an injection of liquid solution). I resumed my attempt to spell backwards. I didn’t make it to “V.”

Then, seemingly five seconds later, I heard the words, “Mr. Dengler, are you awake?” and when I arose from the dead I was so overjoyed that I started laughing out loud, joyously, for having been given the opportunity to live again. Soon, the doctor came in to give me the all-clear and I had to ask him what word he’d asked me to spell because I couldn’t even remember it. “Czechoslovakia” he said and disappeared behind the curtain to go kill someone else.

Pema Chodron writes in the indispensable When Things Fall Apart that we must look to all the things in life that resemble death for the meaning of death. We are already quite familiar with dying by the time it ultimately comes for us, she writes. With every passing year there is a death. Every passing breath is a micro-death. Breaking up with someone is a death. Saying good-bye to a loved one, even if only for an afternoon, is a type of death. Death is everywhere. There is death to be had in all of waking life if only we look for it, a familiarity that will teach us how to die when the moment of the ultimate sleep comes for us.

I am not 50, though I will be before I know it. So will you, even if you’re only in your twenties as you read this. In the grand scheme of things, even the deaths of Caesar, Socrates and Jesus Christ happened really only just yesterday. I have crossed a threshold in hearing the doctor refer me to a colonoscopist. I am now that much closer to the ultimate passing. I passed a big sign that read “The Grim Reaper, This Way” with a big arrow pointing in that direction. There’s something oddly comforting to me about this, a comfort made really tangible by the convincing simulation of death that came with the enforced losing of consciousness before the procedure. I have a little taste now of what it’s like to pass over to another state, one where the sharply demarcated lines of ego consciousness simply don’t abide. There’s a bliss in that and I think I now get it when I read stories of Bodhisattvas passing into the night of the unconscious with little smirks on their faces.

In order to be let out of the hospital I had to have a friend come and pick me up and sign me out. Apparently it’s a state law that someone who’s gone under needs a more conscious being to vouch for them. After he signed me out and we walked out of the hospital, still rubbing my eyes, my friend and I went to go have lunch. He was performing as Bernard in the late ’22 revival of Death of a Salesman on Broadway. We talked about this wonderful crossroads he had now passed: he was officially a Broadway actor now. Just by coincidence a high-end deli had opened around the corner and the owners had invited the cast to christen the new establishment, so that’s where we went to eat. My friend introduced me to Wendell Pierce who was playing Willy Loman. It was a distinct pleasure to shake hands with such an incredible talent and durable presence in our culture such as Wendell only minutes after some flexible, thin probe had concluded its investigation of my colon.

I sat with my friend and we talked. Then we went to check out the new location of Drama Book Shop. Soon, we parted ways. He would go to the theater and catch a nap before his evening performance. I went home to get back to my dogs and my work. It was another day of life.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fame is a Hologram

I remember feeling something funny when I realized that I’d become famous, something akin to a change in climate, like an afternoon breeze had come in. I could sense a shift in certain events which up until then had at times felt confusing or even frustrating and were now much more fluid.

Depending on the time of day and the neighborhood I was walking around in, the heads of passerby, whereas before they seemed oblivious to my bodily existence, now would suddenly turn in my direction—or, if there were two, inwards to each other while giddily whispering.

Depending on the restaurant, the maitre’d who greeted me, whereas before they arched their eyebrow slightly in suspicion, now curled the sides of their mouth and found me a conspicuously available table.

Depending on the venue, the celebrity at the event, whereas before they attended to their careful script of aloofness, now “recognized” me, graciously drew the veil on their mask of indifference and greeted me by my first name.

In many places it seemed like some particularly unhealthy weather pattern had suddenly shifted over to a tropical climate.

The word “recognition” comes from the Latin recognoscere which, transliterated, comes out to “know again” (re + cognoscere). In the Middle Ages, the verb form meant “resume possession of land” and was related to the Old French reconoistre, which looks a lot like “reconnoiter.” The verb was a back formation of “recognizance,” which meant “a bond acknowledging some obligation binding one over to do some particular act” and a little later, “acknowledgment of subjection or allegiance,” as to God or some other type of power or entity.

There seems to be an element of contractual obligation to the etymology. Perhaps our modern usage comes from this: recognition implies an aspect of objectivity. There’s a corroboration that establishes fact, like eyewitness testimony.

If someone “recognizes” you, most often that’s due to having made a previous acquaintance or maybe simply having seen someone repeatedly in the neighborhood. When they recognize you, they are affirming a correspondence (“know again”) between the present and the past, between the you that is right here in front of them and the you that was there before.

Lindsay Lohan knows she is being recognized, being associated with some part of her past, when someone approaches her with a pen and paper. When Charlie Sheen turns a corner on LaBrea and is briefly recognized by an onlooker who happened to catch his passing visage he may not know for sure if he was recognized in that moment, though he would likely place a bet on it if given the opportunity. And when Kanye West offers to consumers of apparel the knowledge of his enthusiasm for contretemps, he may very well be doing so specifically as a reaction to his understanding of his own recognition.

I recall the personal delectation I took in scandalizing interviewers. After a bit of practice it got to the point that I knew somewhere within me I was generating “good copy.” My words would be reproduced in print afterwards and I began to expect that I could hear those words echoed back to me in real life. It felt like I was being heard.

Orson Welles once revealed the secrets of the psychics on a talk show by demonstrating how unconscious is the process by which someone learns to say the right things. Psychics, apparently, are not entirely aware that they are learning a sophisticated skillset, but the rewards are sufficient to reinforce the behavior and they learn to continue it.

The word “recognition” has an interesting sense. Not all artists seek fame outright, but it’s not a stretch to say the overwhelming majority seek recognition. Certainly, the accruing of social capital that comes with celebrity—and which is reinforced by the kind of mass bodily recognition that happens in informal settings like supermarkets—is one of the least displeasurable facets of the experience of fame. But ask any artist, struggling or otherwise, what kind of recognition they hope for and you will likely hear more about the virtues of communication, of relation, of the feeling of placement, of the endowment of honors. In our putatively democratic era these concerns have been deemed empty and frivolous, even déclassé, though during more hierarchical times anxieties such as these around provenance and status had a much more concrete valence. They were seen as perfectly noble goals.

The tension between recognition and fame is what lends cases like Lohan and Sheen and West a degree of tragedy. The pursuits of recognition and fame both comprise essential aspects of the human experience. But recognition, not fame, seems to aspire beyond the confines of the isolated self, seems to persist by dint of a more ennobling cause. Questions of legacy, like questions of family, relate to what happens after we’re gone. These seem like completely legitimate concerns. On the other hand, fame is much more ephemeral and can have a tantalizing, even destructive, effect. Those who fall from grace sometimes seem to choose it, for they know, especially now with the immortal internet, they at least can never fall from fame. Even the ones forgotten by mortals may expect Wikipedia to remember.

At some point in time in my tenure in the spotlight I realized I was about to enter a space I wouldn’t ever be able to leave, a type of Rubicon crossing. I came to have a premonition of some sealed door slamming shut behind me, after which I would be forced to contend for the rest of my life with the hologram of fame that had run before my eyes for several years at that point. I had come to see that whatever apparition the public had been recognizing in me as my body made its way through the world had almost nothing to do with the very real person in whose likeness that media-transmitted apparition had been created. My hologram preceded me everywhere.

I’m always impressed by the Meryl Streeps of the world, who seem to gracefully tango with their apparitions. For the innumerable multitude of photographic facsimiles of Meryl that exist in the universe, she appears as someone who has kept knowledge of the corporeal self, the body and the mind, and cordoned it off from public influence. I heard once that she to this day insists on doing her own laundry. This insistence in doing something seemingly inessential is likely what keeps the integrity of the boundary between herself and the world.

She’d likely made a different decision than I’d made. When she saw that she was about to cross that Rubicon, she did so with the full knowledge that this was her lot for the rest of her life and had knowledge of a certain discipline which would enable her to police what would assuredly be a lifetime of tension between the public and the private selves.

I knew that I had no such discipline.

Yet I also knew, as I think a great so many others don’t have the opportunity to know, that, if I didn’t turn around, if I didn’t take my last chance to take the boat back to the mainland of the more average person, that I would likely grow insane from overexposure to my famous hologram, that I would seek to play with it, toy with it and manipulate it, like my very own “precious,” take enjoyment in seeing how the tiniest alterations to my hologram causes so many conversations, so much speculation, grants me ever more attention. I knew with what paltry self-control I would undertake these little experiments and I became mortally terrified about how addicted to it I would become.

Russell Brand is a bit of a lay addiction expert and has likened the experience of fame to the experience of addiction and he is not incorrect. The sense in which one must treat the experience of recognition as a potential threat to one’s health is what makes fame such a poorly understood phenomenon: it is the most rewarding of addictions and no less for its ability to economically sustain all who surround it. Yet it’s that sustenance, along with society’s cratering into image, into Debord’s “spectacle,” that complicates a better understanding and appreciation of fame’s destructive capacities.

I aver that the cultural obsession with the Wests of the world is missing this critical feature of fame when it undertakes its various expository summations. This would also count for the Lohans of the world and the Sheens of the world, those who at one time or another appear consumed with manipulating their own holograms. It’s impossible to ignore the important aspects of the fetid pool they at one time in their lives stepped into. In West’s example this has to do with issues such as racism and antisemitism, not to mention the obvious fact of his mental illness.

Yet I’m struck how little I hear about the effect of his fame. If Brand is right and fame is indeed an addiction, then a conversation about West’s illness would require an understanding of his fame.

Ten years after the fact, I still obsess over it, playing images in my mind, recalling salad days and glory years, kicking myself for not having the resources of Streep, cursing my lot for being saddled with the deficits of West, reminiscing over the time I had in front of my hologram, marveling over this gift, this “precious,” God had given me which had such sway in the world. I could generate a week’s worth of controversy with the push of a button! What power!

It’s no surprise it would have such a lasting imprint. Bowie dramatized his own crossing of the Rubicon in “Fame,” the vinegar-infused paean that served to purge him of the stresses of the new life he’d gained with his Ziggy success. I am no lyricist and could not piece it together this way. Instead, I write about it, as now.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

25 Ways to do Drugs: Number 9

A man directs a movie, and then another, and then another, until he amasses a reputation as a creator of gritty, urban, depraved, subversive cinema. Then one night he swipes my shoulder with the back of his hand demanding one more twenty to take with him to his cocaine dealer and in this moment his fiction has become his reality.

Am I wrong if I hold him to a higher standard of retaining distance from his creations than the one I abide for my own creations? I see myself as an avatar, my body is my canvas. Rock music is a type of performance art, a bloodsport (it was, at least), and my habits are merely elements in that narrative of performative dissolution. Yet, somehow I see a film director differently.

SETTING:

Luna Lounge was anomalous in the Ludlow Street pantheon of bohemian watering holes that were my semi-adult Disneyland for close to a decade, a convivial and spacious locale with a very uncool foosball table in front and a mediocre stage in a back room. The drinks were cheap and usually free when Dudley, a fellow party-er and erstwhile Interpol touring keyboardist, was bartending. Walking in was to unload from the annoying patter of hipness that were places like the across-the-street Max Fish which lured tourists and wannabes with its reputation as a ground zero for cool dudes. Luna Lounge was not a club in which one made appearances like these. It was a second home in which one put on slippers.

THE EVENT:

The director had been invited by a friend to come hang out and perhaps coordinate a separate visit with his dealer. To this day I haven’t seen all his movies, but the ones I have I adore for their merciless balancing act between the sacred and the profane—though, as far as what goes on on the screen, one would be hard pressed to find particularly memorable instances of the former.

I’d seen pictures of him before, a strong, square-jawed mien, as gritty as his flicks. But I’d never heard him before and hearing him demand that I give him another twenty dollar bill was to hear the raspy extension of an image that I’d already known though his work and his likeness. After I pulled a bill out of my wallet and he grabbed it, he hunched over to count the wad. He looked hard at work, as he might’ve looked talking to a DP on set, discussing an angle. He disappeared and reappeared with powder. In 3D, the mystique was now finally complete.

Interpol had once played a secret show at Luna Lounge, though I can’t recall when that happened on the timeline. Paul Banks, Interpol’s singer, was here on this particular night and, though he was a frequent patron, his presence was nonetheless notable. His presence was always notable for the intensity towards questions of procurement it tended to provoke. Only when Paul was absent did I feel at leisure to decide whether or not cocaine was to become a point of interest.

There’s something of a fever that takes hold when the question of cocaine is raised among a group of drunkards with no alarm clocks to obey. It’s like a horserace where the steeds are separate elements of a fun night: one steed is the bar, the other is the booze, another is the music on the jukebox, still another is the vibe of the crowd and so on. The steeds compete with each other and one of them is the winner the drunks all talk about the next day. Cocaine is one of the steeds but more often than not it’s the slow one, the one bringing up the rear that no one pays attention to. Until certain conditions take hold, like when some of the other steeds start lagging. Then all of a sudden Devil’s Dandruff starts overtaking horses and everyone starts taking notice and placing bets and yelling and jumping off their seats until finally at the finish line she arrives and everyone screams.

This night was one such horserace.

Dudley’s girl, Maggie, was there, a beautiful New Zealander who modeled and who, along with Dudley, did her part from time to time to reenact upsetting scenes from Sid and Nancy, complete with flying vessels.

Her mother was there, too. Which upset me. As a rule, these habits were for me the markers of prolonged adolescence, ritualistic simulacra of truancy and disobedience. That was the reason I so compulsively debased myself and others trying to drink all night and get laid, so that I could bolster the identity of the kid who did what he wanted, never mind how old he’s actually becoming (was I now 32, already?). But in order to sustain that illusion we couldn’t have any adults around participating which would immediately puncture the bubble with reality.

Paul, Maggie, Dudley, Maggie’s mother, the director, the director’s friend and me jumped into the handicapped bathroom to pass around the fresh bags of powder and during the extended holdup of the facility the director started making passes at the mother. Half an hour later the mother fell off her stool and the director was helping her up and the sight of an internationally acclaimed cineaste helping a middle-aged woman to a high chair while both of them breathed in a potent cloud of inebriation redolent with yeast and nicotine instead of doing something more wholesome like possibly getting married and starting a family was too much for me to bear.

What is it like when a newbie private looks up at the top brass and sees the costs of years fighting wars? Maybe it’s like what I felt at that moment. It was one of many chills I often experienced during the relatively brief time I spent being a party monster, frigid spells that I can only say today seem like communiqués from God, warnings about my ability to weather the dangers of proceeding down this path.

Though I don’t know for sure, the director heeded whatever warnings he must’ve been getting after that night. He’s still putting out pictures. I went to see one of them recently and thought it lacked the gusto of his earlier work but I didn’t fault it for that because it was much more imaginative and meditative than any of his previous work, all of which I consider to be a hallmark of maturity. I can only hope that that maturity translates to his being.

I can’t imagine that the beast one channels putting depraved images on a canvas is a particularly docile creature. Some of us come to know this sick boy within us, this shadow of pestilential visions lurking within all humans, and invite him to the table, as that director appeared to have been doing on that night—as I did regularly during all of my afterparties. But this fecund guest whom we refuse to leave in the back shed, as civilization had done for centuries, whom we regularly invite into our homes so that we can get to know it better, so that it may inspire us to continue to depict the infernal with verisimilitude, will one day betray us. It is a wild creature and can never be tamed. And for that we all need to learn tactics. David Lynch uses TM to quell the beast he has regularly summoned to help him produce the tawdry scenes of his camera’s eye. That’s just one example.

I guess I was surprised that the director was letting the wolf off the leash that night. I hadn’t assumed that it was possible to make movies showing wolves off leashes while one had an actual one off a leash. I assumed as much in my case because I believed that, as a rockstar, I was an avatar of destruction. I believed it was part of my job to walk around with a wolf off its leash. But didn’t directors have greater responsibilities? Don’t they have to meet with producers and higher-ups all the time and wouldn’t that get complicated with a man-eating beast around?

The bubble punctured that night. The reality set in. We were a bunch of drunks. There was little more to say than that afterwards. There was no magic in the air. For a moment, even art was lost. There was only a hungry wolf lurking around, terrifying the guests.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Your Marx

“How many different translations of Das Kapital does a man need?”

-my Aunt Martha

I recently paid a much overdue visit to my uncle who lives in Bogotá. The last time I was in Colombia, where a good chunk of my family resides, was in the mid-aughts, back when the aspect of the man I was greeted my family with a different mixture than today. They knew me as a nephew or a cousin, depending on who we’re talking about, who managed to become wildly successful in the music industry and they also knew me as someone with a slightly jaundiced complexion. The two were not unrelated, of course.

My aunt—married to my uncle who is the brother of my mother—has confirmed this impression, if perhaps without the hyperbole I’m certain the above paragraph contains. All she really said was that today, as compared with that erstwhile visit from over a decade-and-a-half, I seem to be a much more open human being, owing perhaps slightly to my greater facility with the Spanish language, but not exclusively so. There’s been a change, she said.

I mention this anecdote because it illustrates most directly how wonderful it is in life when time passes and someone confirms that change has indeed occurred. I may be more restless than average, but, regardless, it seems to be a universal truth that life is about change, so it’s good when there’s proof.

My uncle is a respected political scientist in Colombia and was instrumental in “El Proceso de Paz” and it was easy to detect all this in the way his impromptu lectures unfolded over the first handful of evenings I spent at his house the other week. He has that steady diction of a professor well-accustomed to spontaneous aggregates of clauses and arguments and he deploys rhetorical devices, such as self-questioning aloud, that move his cases forward. I learned more about Colombian history from him during the first part of my stay than in my entire life, along with my own family’s involvement with it.

I’ll write about the particulars of that involvement some other time. Today I’m enjoying looking at the image I’ve pasted at the top of this blog post. This is the view afforded by my uncle’s desk in his study.

As an artist I often question why I’m so drawn to politics. I am especially inquisitive about this recently, as my art has sought to evoke much quieter spaces, such as wilderness settings, than the boisterous and contentious atmospheres that characterize the political sphere. When I engage in political discussions, whether on Twitter or while talking with neighbors, I notice immediately the much more piquant vibe, a saucier texture of staccato rhythms and higher blood pressure, than, say, the singing bowl tintinnabulation of all of my meditation music and nebulous sound baths.

Why, then, do my interests in ideological contestation persist?

I think it’s just the way I’m made. Thanks to my father, I grew up suffused in politics. He was adamant about checking the progress of what he saw as liberal propaganda in the schools and on the television with the alternative framework of his conservative vision. Mostly this turned out to verge on the paranoiac and was almost singularly trained on the illumination of the moral failings of the liberal world view. I grew up with a steady stream of “owning the libs” rhetoric, before that was even a thing.

Sadly for him, his worldview could not compete with the persuasive power of modern media and education, both of which turned out to factor greatly into my turn to the left in my late teens.

I started out on the right and not just because of my dad. Patriarchy and racism were part and parcel of the working class Elmhurst, Queens of the ‘80s which was my home, along with the “small town” car mechanic culture I aligned with in the New Jersey suburbs as a metalhead in the early ‘90s.

Then a real big change happened when Grunge swept through the zeitgeist, when I ditched my suddenly uncool headbanger threads and got interested in more “real” musics which were becoming fashionable in the wake of Seattle’s incursion such as punk-hardcore. The friends I kept in this new circle were decidedly anti-racist—if not entirely non-patriarchal—and were instrumental in ushering me towards the pursuit of a more leftist politics than what I had known up to that point. When I read Kurt Cobain’s slightly hysterical antiracist/antisexist manifesto in the liner notes of In Utero, Nirvana’s follow-up to Nevermind, I hear an echo of the same unease I felt with being connected to a scene with a much more regressive politics than I had come to appreciate by hanging out with all of these leftist punks.

What I learned at that juncture basically stayed unchanged for about twenty years. I went around thinking I was very leftwing, not even aware of how I’d really only learned to appreciate a rather topical issue. Being on the leftwing side of cultural issues is only half of the puzzle, but I still didn’t know that all those years.

I stayed this way until 2020 when I discovered Bernie Sanders and the last vestige of my class interests dominating my politics cracked. I had noticed a sharp drop in my sense of status when I left the music industry and this was fairly traumatic for my ego. I’m still learning from this occurrence—even to this day. I think the reason why I’m so attracted to socialism is because of what that trauma made painfully clear to me: that the higher status I experienced in the music industry occluded my awareness of my own class interests. Socialism, then, with its rational deconstruction of the way social relations are defined by, and occluded by, capital, feels quite logical to me.

I’m struck by the difference between my politics today and the last time I saw my uncle all those years ago. Though I’d been a liberal for quite some time by that point, I still couldn't even define “leftism” back then. The spiritual change in myself that my aunt Martha noticed and took pains to point out correlates with a political one: despite my liberalism (or, some would say, because of it) my class interests when she first saw me over fifteen years ago dominated my politics. I read the New York Times every day and believed every neoliberal word that jumped out of the page. I could only see in the binary of left and right a difference in culture and failed to see the much more troubling economic consensus of class interests between both the left and the right that characterizes that paper’s program. In other words, when I looked at the above image over my uncle’s desk, I saw only a dude in a long beard and knew very little of the radicalism behind his thought, how Marxism demolishes the neat binaries of mainstream media.

Unlike my father, my uncle had no say in my turn to the left, the more recent, much more authentic, turn I have taken. Or, if he did, it was all rather indirect. The internal reverberations of the things I learned on this trip to Bogotá about my family’s political history, on the Colombian side, my mother’s side, are going to echo within me for a long time. Yet, already, I can see something that has happened conclusively and maybe it’s something that actually points out of the political arena, to a truth about what it means to be part of a family in general.

For if there is indeed an invisible line that ties us to our blood relations and to our ancestors and to our descendants, if there is some kind of spiritual thread that binds members of clans together, irrespective of narrative or persuasion, something, that is, ontological which links us as members of the same family, irrespective of conscious awareness, such that one might be able to talk with objectivity of family curses and family spells and family spirits, if all of this is indeed true, then it was with some wonderful recognition of the homecoming of a journey that I was able to see this poster hanging up on the wall in front of my uncle’s desk and notice that, independently of any possible influence he could’ve had over the last fifteen years, I had connected with a spirit within me that was older than I was.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

What I'm reading, June, 2022

Already by page 10 and I’m in a world of such specific—though somewhat airy—subjectivity that I’m convinced once again just how easy it is for a reader to feel at home within the solipsistic realms of writers daring to make such marvelous furniture out of their thoughts, feelings and perceptions. It’s like a magic trick that, rather than making us awestruck over some supernatural occurrence, makes all that is actually outside of the trick—the “trick” here being the conjuring of a subjective world by the memoirist—the uncanny thing, as opposed to the dependable, canny one we think is this more quotidian world.

I’m consumed by the thrill of continuing to read this book and am so looking forward to closing it on its final page just before I leave for Alaska so that the week I shall spend amidst the tundra and the permafrost will be imbued with the freshly opened spaces this book is already inserting into my consciousness. I leave for this epic trip next weekend. I expect it to be even more transformative as a result of having finished this book.