Text

Class #14: Methodological Pragmatism and Pluralist Implications

Andrew Light begins “Methodological Pragmatism, Pluralism, and Environmental Ethics” by describing his proposal of an environmental version of pragmatism He says this development stemmed from his, and many others, frustration that the field of environmental ethics was not making enough significant contributions to the resolution of environmental problems. Other fields, he thinks, such as environmental history and sociology were making great progress. He believes the lack of progress in the field of environmental ethics has to do with the “particular fixations of environmental ethicists, which may have been partially influenced by broader trends in academic philosophy in general” (Light, 319). In other words, he thinks many philosophers have been debating conceptual matters that can’t really be applied to real-world problems. And if the field of environmental ethics has not made any significant contributions, he wonders what’s even the point of having these ethics? As a result, he has turned to this methodological environmental pragmatism, which he believes both a pragmatist and non-pragmatist could use as a tool. Many accounts express a form of monism rather than the pluralism Light sides with. “Monists in environmental ethics argue that a single scheme of valuation is required to anchor our various duties and obligation in an environmental ethic” (Light, 321), citing Calicott as an example. Pluralists, like Light, believe it cannot be possible that there could only be one ethical theory that covers such a range of objects, “because the sources of value in nature are too diverse to account for in any single theory” (Light, 321). Light believes the drive to create a more pragmatic field of environmental ethics is motivated by the desire not to participate in resolving environmental issues, but to hold up the philosophical end among the environmentalist community. And if philosophy is to serve a larger community, then it must allow the plural interests of that community to help determine the philosophical problems to be addressed. As a pluralist, Light believes we should be able to choose one tool or another tool depending on the situation we’re in. He thinks the twisting or manipulating ideas is permissible if it will sway the audience you are trying to reach. For example, if you are talking to an anthropocentrist, it is okay to argue within an anthropocentric framework if you think it will allow you to achieve your goal of making changes. Light believes the very role of the philosopher is to make public changes. And beyond that, to act as moral translator. He believes the philosopher has the responsibility to communicate the consensus that has been reached in environmental ethics in a way that makes sense to the public. As a result, Light believes a more pluralist and pragmatic philosophy could better serve the environmentalist community and solve many of the problems his own methodological pragmatism presents.

I know there have been concerns expressed with pluralists and their connection to moral relativism, and I wish Light addressed that a bit more in this article. In other words, ethical propositions might not reflect objective truths, but instead, make claims relative to more personal circumstances. This kind of ties back into the idea that pluralists might choose the easiest tool to make their argument as opposed to the most fitting, appropriate or effective tool. As a result, it is hard to fully support the theory when its problems have been, in a way, danced around.

0 notes

Text

Class #13: Two Factor Egalitarianism as Interspecific Justice

As VanDeVeer says in “Interspecific Justice,” forming an “adequate theoretical basis for the legitimate treatment of animals and cannot be done simply by extending...principles” (VanDeVeer, 151). Instead, VanDeVeer aims to look at a variety of theories, identifying both three forms of speciesist and two nonspeciesist views, in order to develop an adequate theory of interspecific justice. The views are, respectively, 1. Radical Speciesism, 2. Extreme Speciesism, and then, 3. Interest Sensitive Speciesism, 4. Two Factor Egalitarianism and 5. Species Egalitarianism. Radical Speciesism and Extreme Speciesism extend no intrinsic value to nonhuman animals, and the interests of humans are inherently weightier than that of animals. While Interest Sensitive Speciesism tells us that one may not subordinate a basic interest of animal for the sake of promoting a human interest, Species Egalitarianism tells us it is morally permissible to subordinate the peripheral to the more basic interest and not otherwise. VanDeVeer himself, however, seems to support Two Factor Egalitarianism, which tells us that “The subordination of basic animal interests may be subordinated if the animal is psychologically ‘inferior’ to the human in question” (VanDeVeer, 154). So in conflict of like interests, between humans and animals, it is important to focus less on these levels of interest, as this may fail to take into account matters of what is actually important. In summary Two Factor Egalitarinism assumes “the relevance of two matters: (1) level or importance of interests to each being in a conflict of interests, and (2) the psychological capacities of the parties whose interests conflict” (VanDeVeer, 157). For example, this would justify sacrificing one’s dog for its resources if you were stranded on a life raft. “It is not simply that human interests are, after all, human interests and necessarily deserving of more weight than comparable or like interests of animals. The ground is rather that the interests of beings with more complex psychological capacities deserve greater weight than those with lesser capacities” (VanDeVeer, 158). Overall, he believes Two Factor Egalitarianism to be the most acceptable proposal of how we treat animals, but also believes this is not an easily formulated principle.

I think VanDeVeer offers a sound view of the treatment of animals. At a distance, it seems he has found the happy medium of the two proposed viewpoints of Singer and Regan with Two Factor Egalitarianism. However, I do think the Two Factor Egalitarianism perspective offers a kind of hierarchical positioning of humans and animals, particularly when VanDeVeer discusses the degrees of sentience among the two groups, and I feel as though that is what got us into this debate in the first place. So I wonder if determining degrees of sentience among humans and animals is any better than what Singer and Regan proposed after all.

Word Count: 459

0 notes

Text

Class #12: Animal Liberation is Not a Polar Debate

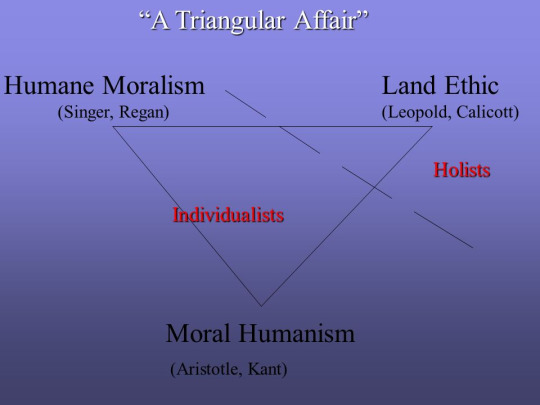

Calicott’s “Animal Liberation” tells us that the debate surrounding animal liberation has previously been set up with two sides: those who argue that animals lack moral standing those who argue that animals have sentience, rationality and feelings, and therefore, do have possess moral standing. More specifically, these two positions outline moral humanism and humane moralism. Calicott suggests in this essay, however, that Leopold’s land ethic offers a third position to this debate, making it a triangular affair rather than a two sided one. Calicott believes Leopold’s foundation of environmental ethics should be included in the discussion of animal liberation with the goal of forming one, sound ethical theory, “Animal liberation and animal rights may well prove to be a triangular rather than, as it has so far been represented in the philosophical community, a polar controversy” (Calicott, 18). I have attached a visual display of this triangular affair that helps to aid in its clarification.

Calicott thinks it makes sense to include environmental ethics for a number of reasons. The first being that it would be easy to integrate into the conversation based on its similarities. For example,we know the land ethic is a holistic ethic where “a thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community and it is wrong when it tends otherwise” (Leopold, 224). This shares similar goals and values to moral humanism and humane moralism. However, and more importantly, all three of these positions could not adequately address the concerns of animal rights and liberation. For example, humane moralism believes in the rights of all sentient creatures, but moral humanism allows certain members of the biotic community to be treated as the mere means to an end. The land ethic is more holistic than these two individualistic theories. And they differ on positions such as liberating animals, while the more individualistic views would argue to liberate domestic animals and the latter would argue more on behalf of the environment it would change, “Concern for animal (and plant) rights and well-being is as fundamental to the land ethic as to the humane ethic, but the difference between naturally evolved and humanly bred species is an essential consideration for the one, though not for the other” (Calicott, 32). In other words, the land ethic aims to maintain the ecological whole in contrast to moral humanism and humane moralism. Calicott argues that only when all three theories work together can a sound ethical theory emerge for the animal liberation movement.

A question I have about this article stems from Calicott’s claim that liberating domestic animals would be pointless. He believes these animals would die or go feral in the wild, and destroy the environment with its competition with wildlife. But I wonder if the same then could be then be said for the many different plants that rely on humans to flourish and grow? Would we not have to extend the same set of ethics to any nonhuman being? What would Calicott think?

Word count: 486

Works Cited:

Miller, Shana. “Animal Welfare and/or Animal Rights.” Slideplayer, https://slideplayer.com/slide/6664624/

0 notes

Text

Class #11: Experiencing Subjects of Life and Rights

Similarly to Peter Singer, Tom Regan identifies as an advocate for animals. However, most of their similarities end there. Singer identifies certain relevant consequences from practices like eating meat and wearing fur: that the animals would suffer. But Regan locates the problem behind such relevant consequences in his piece. It is evident from the beginning of “The Case for Animal Rights” that Regan rejects Singer’s utilitarian view that states we should count human interests as equal with animal interests. With utilitarianism comes the idea that individuals do not hold any value themselves, as they are merely receptacles who hold said value and pleasure. Regan instead argues that it is crucial to not treat the individual solely as a means to an end. For example, a utilitarian could potentially justify the use of animals in scientific research, if the benefits were sufficient enough. Whereas Regan argues to abolish practices like animal experimentation on the basis that we would be treating animals merely as a means to human ends, “Here for us—to be eaten, or surgically manipulated, or put in our crosshairs for sport and money. Once we accept this view of animals—as our resources—the rest is as predictable as it is regrettable” (Regan, 143). This is because Regan believes any individual that is an experiencing subject of life has a certain inherent value and moral standing. However, being an experiencing subject of life is not the same thing as simply being alive. An experiencing subject of life would be anyone who experiences the concepts like having feelings, awareness, and their own preferences. And Regan believes once you obtain this label, and hold this inherent value, you are owed certain things. This is because any being who can value their own life should not be treated as a resource or as if it exists solely to benefit others, “We must recognize our equal inherent value, as individuals, reason--not sentiment, not emotion--reason compels us to recognize the equal inherent value of these animals” (Regan, 148). Regan believes if we are going to include all humans in having rights, it would be wrong to experiment and eat animals for the same reason it would wrong the perform experiments on severely disabled humans, as any limitation of rights we tried to set would also be imposed on them.

Even beyond the throwing around of the word “retarded,” I think Regan’s viewpoint is a bit too narrow, as it suggests only experiencing subjects of life have inherent value. While I disagree with Singer as well, I think both Regan and Singer offer rather extreme perspectives. I don’t think all creatures have equal worth, but I don’t think only experiencing subjects of life hold value. I think if Regan broadened his view a little, the theory would prove more effective, and be more applicable to the animal rights movement as a whole.

Word count: 475

0 notes

Text

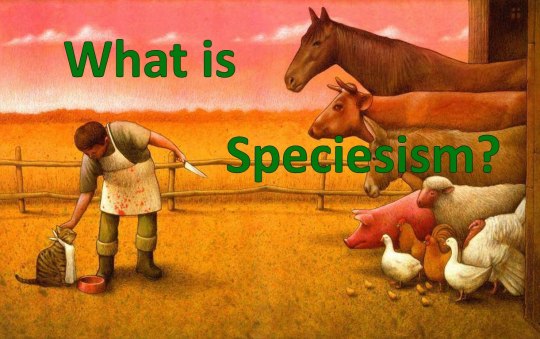

Class #10: Speciesism and The Extension of Equality

Peter Singer frames his argument in “All Animals are Equal” against speciesism by suggesting there is no reason to deny the fact that sentient beings have equal interests to human interests. Contrary to philosophers like Goodpaster and Taylor, Singer believes this extends to sentient beings and sentient beings alone. Singer believes the problem lies within our moral principle of equality. He suggests that our current attitudes and behaviors operate in a way that only work to benefit one specific group, usually our in-group, at the expense of another group. This leads us to speciesism or the belief that the interests of one’s own species outweighs the interests of all other species. From a utilitarian perspective, speciesism can be viewed as a completely unjustified bias. Utilitarian principles aim to maximize pleasure and minimize pain, so whose pleasure or pain it is, whether it be human or nonhuman, is irrelevant. We can see this further in how he argues against eating meat as well as animal experimentation. As Singer says, “None of these practices cater for anything more than our pleasures of taste, our practice of rearing and killing other animals in order to eat them is a clear instance of the sacrifice of the most important interests of other beings in order to satisfy trivial interests of our own” (Singer, 31). However, the extension of our moral principle of equality does not suggest we have to treat nonhumans the exact same way we treat fellow human beings, but “The basic principle of equality, I shall argue, is equality of consideration; and equal consideration for different things may lead to different treatment and different rights” (Singer, 27). Singer also proposes that speciesism is a prejudice no less objectionable than racism or sexism. He believes the extension of our moral principles should not be strictly humanist, in order to combat these prejudices, but aim to combat speciesism as well, “It is significant that the problem of equality, in moral and political philosophy, is invariably formulated in terms of human equality” (33). Although most of us are not racists ourselves, many of us are speciesists, and we have to extend our moral principle of equality to all members of our community, not just within our own species.

I have a lot of problems with Singer’s piece. The equation of speciesism with racism and sexism, the light hints at infanticide, and so on. Yet, I think my main problem with this piece is Singer’s interpretation of what interests are. Singer argues that since nonhumans desire to not experience pain, they have interests the way humans do, but that could lead to a complicated conclusion. With this logic, receiving an antibiotic for a bacterial infection would be wrong, that our desire to kill the bacteria within us does not outweigh the suffering the bacteria would experience. I think he has confused interests and desires, and this has lead his piece to a rather extreme place.

Word count: 489

Works Cited:

Monson, Shaun, Persia White, Moby, Maggie Q, and Joaquin Phoenix. Earthlings. Burbank, CA: Earthlings.com, 2010.

0 notes

Text

Class #9: How Far Does Consideration Go?

In some ways, Goodpaster’s “On Being Morally Considerable” essay acts as the basis for what Taylor argues in “The Ethics of Respect for Nature.” While Taylor seems to have all the answers already, Goodpaster contemplates in his piece what makes a being worthy of moral consideration. As he writes his essay, he is trying to figure out who and what has moral standing, and what the requirements are to gain said moral consideration. As he shapes his argument, Goodpaster states that he personally believes it is wrong to say rationality or the capacity to experience pleasure and pain are the only conditions that make an individual worthy of this moral consideration. In fact, Goodpaster argues that being alive is simply sufficient enough criteria to be considered, which can seemingly align him with the biocentric view Taylor presents in his essay. However, Goodpaster does want to make the distinction between moral rights and moral considerability clear. Goodpaster believes moral rights is something that exclusively applies to humans, whereas moral consideration tells us that while non-humans do not have to share those moral rights with us, this should not prevent them from being considered morally themselves. For example, Goodpaster believes sentience alone should not deem what we find morally considerable. Sentience itself is an adaptive characteristic, as it provides an organism with a better ability to avoid the threats life presents it with. As a result, when deciding what merits moral consideration, we need to start with life itself as opposed to sentience or rationality. Goodpaster appeals to Feinberg's “interest principle” here. The interest principle has two components: the first is that only beings who can be represented can receive moral consideration, and to gain that representation, one must have interests. The second component is that in order to gain moral consideration, one must have their own interests with the capabilities to be benefited. Goodpaster is saying that he believes in the importance of welfare-interests, as something that lacks the ability to take interest in something, such as a plant, still has things that are in its interests, like how it is in the plant’s interests that it is in the sunlight and is watered regularly, “Psychological or hedonic capacities seem unnecessarily sophisticated when it comes to locating the minimal conditions for something's deserving to be valued for its own sake” (320).

Goodpaster successfully defines what he believes is worthy of moral consideration. My question here would be if certain obligations stem from this consideration, even though Goodpaster might argue against this. Since it is in a plant’s interests to be watered regularly, do human beings, or rather capable beings, not have certain moral responsibilities to carry this out? Should moral considerations necessarily lead to moral actions? Is being morally considered quite enough for nonhuman members of our community?

Word Count: 466

0 notes

Text

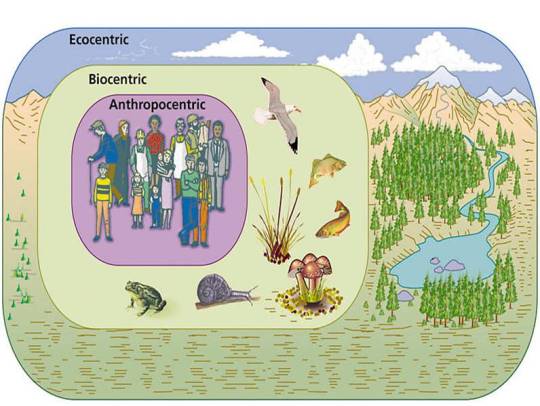

Class #8: Biocentrism's Extremism

In “The Ethics of Respect for Nature,” Paul Taylor argues for for a life-centered system of environmental ethics, where the well-being of individual organisms determines our moral relations. In other words, Taylor believes we should have respect for every living organism in our community, as each member has equal worth. This life-centered viewpoint is better classified as biocentrism, or a system of ethics that aims to protect all life in nature. Biocentrism also suggests we should not let our strictly human desires govern the choices we make in regards to our environment. This theory obviously contrasts the anthropocentric view we have discussed in class, that tells us “We have no obligation to promote or protect the good of nonhuman living things” (Taylor, 198). But it also opposes the idea of sentience-centered ethics which is something that has been proposed by philosophers like Peter Singer. This is because Taylor believes all living organisms are equal in their value, regardless of sentience. He argues for “the interdependence of all living things in an organically unified order whose balance and stability are necessary conditions for the realization of the good of its constituent biotic communities” (205).

To further make his argument, Taylor proceeds to tell us biocentrism’s four main components. He first tells us that humans are thought of as mere members of the Earth’s community of life. This suggests that evolution brought every member of the biotic community into existence, and human beings are no more important than any other member as a result. This leads into the second component: Earth’s natural ecosystem as a totality is seen as a complex web of interconnected elements. In other words, everything is connected to everything that surrounds it. The third component tells us that each individual organism is conceived of as a teleological center of life, pursuing its own good in its own way. So we are all goal-directed beings, and having welfare-interests is enough to be deemed morally considerable. An example of a welfare-interest is how a plant seeks light to survive, and regardless of the plant’s lack of sentience, ignoring its welfare-interests could drastically harm the plant. And without welfare-interests, there is nothing to morally consider. The final component states that any claim that tells us humans are superior to other species is completely groundless, and must be rejected as an irrational bias in our favor. This brings us back to the idea that humans have the exact same value as any other being in nature, “Once we reject the claim that humans are superior either in merit or in worth to other living things, we are ready to adopt the attitude of respect” (Taylor, 217).

The biocentric view seems to be the polar opposite of the anthropocentric view, as well as one of the more extreme views we have read about. I tend to find myself leaning away from anthropocentric views, as I always have, but the biocentric view leaves me with a few questions about its extremities. While I don’t support the human superiority Taylor addresses in the fourth component of biocentrism, I do wonder if we can hold biocentric views without backtracking our advancements in other fields of ethics. If we believe all beings are equal, would we not have to extend all the rights we have given to humans to our animals and plants? Is there a way biocentrism can be a mere addition to our already standing ethics, like the land ethic?

Word count: 575

Works Cited:

Eco110Dejan. “Eco110Dejan.” Wordpress, “https://eco110dejan.wordpress.com/”

0 notes

Text

Class #7: Ecological Self-Realization and Gandhi

Naess opens his piece by establishing that humankind has always wrestled with certain questions about who we are, where we are meant to be and the meaning of our very existence. Within his essay, Naess aims to answer many of these questions through an exploration of the self and the world that surrounds mankind. Early on in the piece, he introduces the concept of the ecological self, saying “We may be said to be in, of and for Nature from our very beginning. Society and human relations are important, but our self is richer in its constitutive relations. These relations are not only relations we have to other humans and the human community” (Naess, 14). In short, Naess believe we have to be in touch with the environment that surrounds us, and not only then will we live happily and compassionately, but with a greater meaning and purpose. He offers to central ideas: 1. The Western notion of the self is incomplete and in need of a new concept of the self, and 2. An environmental ethic should not require self-sacrifice and duty alone. Naess believes we should aim to live with a purpose that is bigger than our own egos, and we should all aspire to have the same realization that Gandhi did when he “recognized a basic, common right to live and blossom, to self-realization in a wide sense applicable to any being that can be said to have interests or needs” (23). He cites an example where he experiences this compassion himself within a non-human, “It took many minutes for the flea to die. Its movements were dreadfully expressive. What I felt was, naturally, a painful compassion and empathy. But the empathy was not basic, it was the process of identification, that ‘I see myself in the flea’” (15). From this, we can assert that Naess believes it was through this process of identification that he allowed him to feel this compassion, as well as a means by which humans can experience solidarity. This is an important point stressed in the essay, as Naess believes Human beings have to identify themselves within plants, animals, and landscapes in order to help them. With this process of identification, we are able to not alienate ourselves from these other species. And as Naess says in his conclusion, when the ecological-self is “introduced, the concept of self-realization naturally follows” (29).

In his essay, Naess was able to take the concept of self-realization and apply it to what he called the ecological self. He tells us how human beings could achieve an ecological conscience through the process of identification, which would allow us to further connect and feel compassion for our biotic community. His appeals to Gandhi and Buddhism not only added a diverse perspective and helped put his ideas in a larger context, but allowed him to broaden the lens of self-realization. Like Naess, Gandhi recognized that non-humans deserved their own consideration, and through this, both Gandhi and Naess thought the goal of self-realization would be achievable. I found an interview Naess did that I found helpful when writing this post, particularly at around the 7:50 time mark.

youtube

Word count: 537

Works Cited:

Naess, Arne. “Arne Naess and the Deep Ecology Movement (short version).” Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GJz2zVW9WHM

0 notes

Text

Class #6: Ecosystems and Where We Find Obligations

In the past, we have set our ethics in place to protect the individual from the tyranny of its surrounding community. Rolston in “Duties to Ecosystems” argues that we should instead aim to strike a certain balance of these two categories, particularly in the field of environmental ethics. Rolston believes that our duties to the community and our duties to the individual don’t have to necessarily replace one another. He believes the problem lies in how we attach our duties and respect to the individual. We often only attach our values to the coherent whole, harmony/reciprocity and high levels of organization that we can see solely at the level of the individual, from the skin in. As a result, we don’t find any value in the community because we are looking for those same characteristics in a place where they don’t exist. From the skin out, communities, like ecosystems, offer us jungle-like chaos, riddled with competition and random organization. We won’t find the same harmony and organization in the community, but according to Rolston, looking for these characteristics is a category mistake. Our duties and respect should not attach merely to the qualities of the individual, “What we want to admire in nature, whether in individuals or ecosystems, arc the vital productive processes, not cooperation as against conflict, and ethicists will go astray if they require in nature precursors or analogs of what later proves admirable in culture” (Rolston, 249). It is not uncommon for philosophers to argue that ecosystems are beyond our consideration, as we often hold nature “to have only instrumental value for humans, regarded as the sole holders of intrinsic value” (Rolston, 268). However, Rolston argues that there is a complex relationship between the instrumental and intrinsic values present in our ecosystems. “The system is a web where loci of intrinsic value are meshed in a network of instrumental value” (269), this leaves us with a certain systematic value. And Rolston argues that our ethics are not complete until we extend them to these systems. Mankind owes it to the ecosystems as a result of this systemic process.

The question that arises from the text is if we should regard our communities as more important than the individual? Rolston, in this text, aims to bridge the gap between the two. He suggests there is a connection between the individual and the community, and we can find both intrinsic and instrumental value in our biotic community. However, he argues that individuals are temporary, producing far less than our ecosystems. And yet, our ethics are set up to benefit the individual far more. Is it feasible that integrating our communities and their values in our ethics is merely an extension of our existing ethics? Or is it a complete reversal of what we find value in?

Word count: 469

0 notes

Text

Class #5: Holistic or Ecofacist?

As we know, Aldo Leopold is not a philosopher. His text provides the framework for “The Land Ethic” without any philosophical foundations. J. Baird Callicott, however, proves to be a rather successful philosopher and aims to take Leopold’s “Land Ethic” and address the concerns raised by many of his fellow professional philosophers. In “Holistic Environmental Ethics and the Problem of Ecofacism,” Callicott aims to address the land ethic’s entanglement with ecofacism. Ecofascism is a term used to accuse certain environmental activists of totalitarianism, and Callicot attempts to defend the land ethic from receiving this label from critics like Tom Regan. Even more so, Calicott wants to attempt to make the land ethic more systematic. He wants to make the ethic easier to understand and easier to understand the ways in which it can be implemented. To do this, Callicott begins his piece by outlining the origins of ethics as a whole. He does so by citing a number of great minds, namely Charles Darwin. In short, Darwin believes the following: “without some rudimentary ethics, human societies cannot stay integrated” (Callicott, 62). In other words, ethics were founded as a means to survival in our communities. The social sentiments and impulses humans have evolved with supply us with the foundations of ethics, according to Hume and Smith. And in “The Land Ethic,” Leopold takes Darwin’s explanation for the emergence of ethics even further by adding an ecological element. Leopold took “over Darwin’s recipe for the original and development of ethics” and added, “an ecological ingredient, the Eltonian ‘community concept’” (66). In simpler terms, Leopold is building on Darwin by adding this ecological element and community concept into far larger boundaries. Darwin himself found problems with philosophers aligning the origins of ethics with reason. He discovered that to develop reason you have to be already within a social environment, and to be in a social environment, you have to already have ethics. And this brought Darwin to develop his account, and Leopold merely builds on Darwin’s beliefs with his land ethic.

However, concerns begin to arise from philosophers that believe conservationists are merely “concerned about biological and ecological wholes—populations, species, communities, eco-systems—not their individual constituents” (68). This concern for the whole rather than the parts is great for conservationists but does not do much for those concerned with the ethics surrounding it. Holism is the land ethic’s principal asset, but also its principal liability, justifying actions in parts of the biotic community that would never be acceptable in the human community. An example of this would be the way we manage wildlife. This is arguably a form of ecofacism due to its requirement that individual organisms, including “human organisms, must be sacrificed for the good of the whole” (70). To combat this take on the land ethic, Callicott asserts that “the land ethic is intended to supplement, not replace, the more venerable community based social ethics, in relation to which it is accretion or addition” (75). Essentially, what Callicott is arguing on behalf of Leopold, is that our concern for the land should not replace the concern we have for our fellow man, but expand that concern to the land as well. The land ethic is just an accretion or addition to our existing ethics, not a supplement or substitution. Callicott is merely suggesting we adhere to the land ethic’s principles of 1 obligation generated by membership in more intimate communities taking precedence over those generated in impersonal communities, and 2 stronger interests generating duties that take precedence over duties generated by weaker interests.

Surely, I agree that the land ethic is not meant to replace our community based social ethics. What Leopold and Callicott are arguing for should definitely be an addition to the ethics we have in place, where our community expands to include our land as well. However, I can’t help but wonder if what Callicott is proposing is perhaps too holistic. I think ecofacist is a strong word, but I can see how many professional philosophers find problems with this ideology’s concern for the whole. For instance, while expanding our community is certainly necessary, should our land be given the same priority as our human community? Doesn’t the land ethic seem to suggest we have to treat human beings as we treat every other animal? Is there perhaps another way to arrive at Callicott’s point about expansion that does not come across overly holistic?

Word Count: 743

0 notes

Text

Class #4: Environmental Conservation in an Economically Driven World

There is a quote that struck me while reading “Thinking Like a Mountain;” “We all strive for safety, prosperity, comfort, long life and dullness” (Leopold, 133). I am the first to admit that I lead a very privileged life, and upon reading this sentence, I realized I did not strive to obtain any of these concepts at all. In my case, these concepts should more likely be considered guarantees. It puts things in perspective to recognize that the same could not be said for our plants, animals, soils, and waters—what we have come to know as our biotic community. As Leopold explains in “The Land Ethic,” at the time, there had been little to no ethics dealing with man’s relations to the land. The need for that consideration, however, is still dire, and Leopold calls for it by asking the reader to extend the morality and ethics we apply with one another in our human-centered communities to the land we live on as well. In his words, “The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants and animals, or collectively, the land” (204). Leopold believes it is crucial to change mankind’s role as the conqueror of our community to simply a member of the biotic community. We are not the all-powerful beings we dream ourselves to be—we are also members—and we should aim to enlarge our understanding of the community we have ignored. Leopold’s frustration with this lack of ethical extension and consideration is evident in “Thinking Like a Mountain” when he discusses the extirpation of wolves. He says that he has “watched the face of many a newly wolfless mountain, and seen the south-facing slopes wrinkle with a maze of new deer tails… In the end the starved bones of the hoped for deer herd, dead of its own too-much, bleach with the bones of dead sage, or molder under the high-lined junipers.” (130) As Leopold explains in a later chapter, things like this only happen because we treat our earth as a mere commodity. Our relationship with our land is one that is strictly economic; it is not our wolves that we care about, but the fact that they provide so little for our benefit. We have disregarded that wolves do, however, provide a lot for other members of the biotic community. Leopold briefly touches on the relationship between wolves and deer. Upon further research, I discovered wolves do not merely help control deer populations, but they affect the very behaviors of deer. Deer started avoiding places where they could be trapped by wolves, and from their lack of grazing, areas that were previously barren regenerated rapidly. This is evident in a video from Sustainable Human entitled “How Wolves Change Rivers,” which I have attached here:

youtube

Bringing this back to Leopold, it is hard to wrap one’s mind around why we treat animals and plants as property to be sold and owned, “The land relation is still strictly economic, entailing privileges but not obligation” (203). One could likely tie this back to the anthropocentric worldview, that insists things like land are of a mere instrumental value. This worldview also holds humankind to a higher position then the land, and as we know, Leopold thinks it is necessary to change this. As he says, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise” (224). This is what should govern our land ethics, not an anthropocentric view with economic implications.

It was troubling to see on paper how our land-use ethics are governed by sheer economic self-interest. Reading about our how even our soil conservation laws were in place solely for the benefit of farmers made me realize that I couldn’t name a single environmental conservation law that we as humans do not reap the benefits from. I think this fact only further proves the need for the land ethic. Not only did Leopold bring to light how economically motivated the nature of our environmental concerns are, but he highlighted how stilted our land use ethics are. Our social ethics are no longer governed by economic interest, why should our land use ethics be? It is hard for me to imagine a world where any society practices environmental conservation out of the good of their hearts, but I can’t help but wonder if there was less of an economic motive, would environmental conservation prove more successful?

Word Count: 761

Works Cited:

Sustainable Man. “How Wolves Change Rivers.” Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysa5OBhXz-Q

0 notes