Text

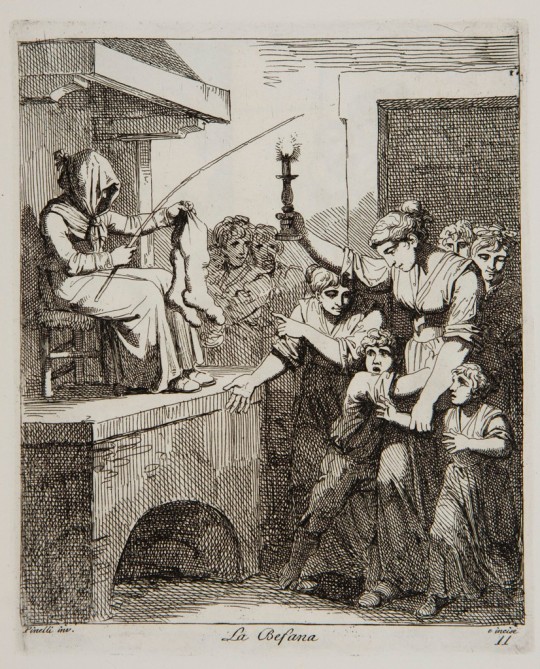

The Night of La Befana

The Night of La Befana was recorded as early as 1549, when Agnolo Firenzuola has Golpe (one of the characters that appears in his poem La Trinuzia) mention this widely celebrated tradition.

Although the Roman artist, illustrator and engraver, Bartolomeo Pinelli represents the nineteenth century Befana as being relatively well-dressed, she is generally described as an ugly crone, wearing ragged vestments. A Roman nursery rhyme describes her as follows:

“The Befana comes at night

In worn out shoes

Dressed like a Roman

Long live the Befana!”

Said to travel over the rooftops of Italy on her broom, leaving chocolates and candies for the good children and coal for those who have misbehaved, she enters their houses via the chimney and exchanges her gifts for offerings of cake and wine. Accordingly, a nursery rhyme from the Puglia region relates to this part of the legend.

“The Befana comes at night

In worn-out shoes.

For the small, little children she leaves a lot of little chocolates,

For the bad little children, she leaves ashes and coal.”

As far as Christian traditions are concerned, there are two stories that relate to the Befana. In the first, the The Wise Men (or Magi) stop at her house to ask directions to Bethlehem, as they are following a star, which will lead them to the newborn Son of God. They invite her to come along with them, but she refuses. She is after all, busy sweeping her house. Later she realises the magnitude of her decision and decides to follow after them. Her broom magically allows her to mount it and she flies away. Unfortunately she cannot find the Magi nor the baby Jesus and instead, continues to fly over Italy, providing gifts to little children at Epiphany.

The second Christian myth that attempts to explain the origins of the Befana begins with King Herod’s Massacre of the Innocents. Herod, in his haste to rid the world of the Lord Jesus, decreed that all male children of a certain age would be killed. One of the mothers whose son is murdered is so desolate and aged with grief that she refuses to believe that her child is dead. Instead she bundles up the boy’s belongings and set out to find him. Of course she does not succeed, although she inadvertently happens upon the Christ-child and the Holy Family. Accordingly, she offers her son’s belongings to the baby Jesus and for this selfless act, is rewarded by Saint Joseph. For one night, every year, until the end of time, the Befana is permitted to treat all of the children of Chrisendom’s as her own and bestow gifts on them as she pleases.

References: Agnolo Firenzuola, Opere di Messer Agnolo Firenzuola Fiorentino, Volume Quinto, Milano, 1802, p. 41.

Jo Linsdell, “The Legend of La Befana.” In The Florentine, 14 December, 2006.

Lisa Yannucci, “La Befana vien di notte.” Available at Mama Lisa’s World: International Music and Culture. https://www.mamalisa.com/?t=es&p=3102

“The Befana.” https://www.italyheritage.com/traditions/christmas/befana.htm

Images: Bartolomeo Pinelli, La Befana, the Old Woman who Comes down the Chimney at the Feast of the Epiphany to bring Gifts for Young Children, 1820, print, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Professor C. E. Norton. © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

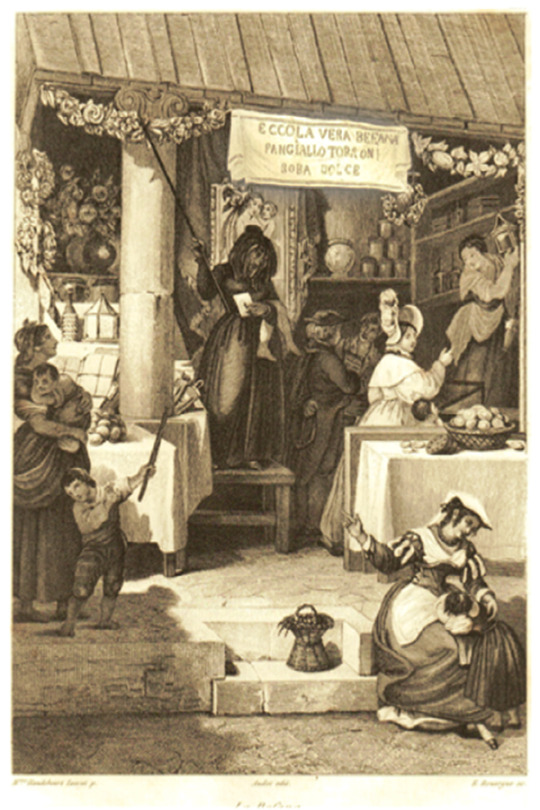

La Befana Selling Sweets and Nougart in Piazza Navona During Epiphany, 1836. De Agostini Picture Library. Editorial Use Permitted.

La Befana, 1821, etching on laid paper, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. Gift of Ruth Cole Kainen. © 2018 National Gallery of Art.

Posted by Samantha Hughes-Johnson.

259 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By Alexis Culotta

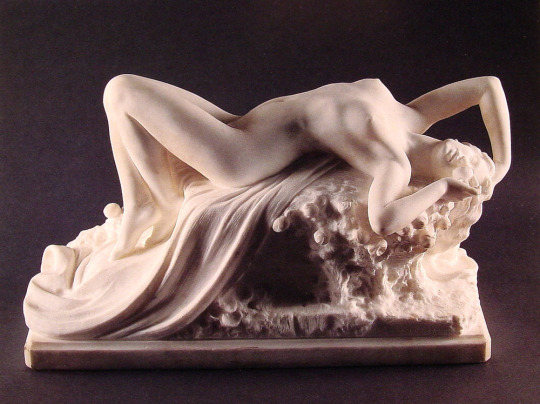

Reaching his end in Rome: sculptor Costantino Barbella died 5 December 1925. Born in 1852 in the city of Chieti, nearly due east of Rome near the Adriatic coast, Barbella began his artistic career modeling small figures for presepe scenes. His growing acclaim from these early figurines eventually won him a scholarship from the city of Chieti to attend Naples’ Royal Academy of Fine Arts. While there, Barbella developed his talents in small-scale sculptures rendered in marble and bronze. Barbella’s international presence grew over the course of the 1880s and 1890s as he played a pivotal role in both the 1884 International Exhibition in Antwerp, Belgium, as well as the 1899 International Art Exhibition in Venice.

Barbella remained relatively active as an artist until late in his career, when blindness began impacting his ability to sculpt. Today, a museum in his honor, the Museo d’Arte Costantino Barbella, stands in his hometown as a celebration of his artistic talent.

Photograph of Costantino Barbella.

Detail of Francesco Paolo Michetti, Portrait of Costantino Barbella, Museo d’Arte Costantino Barbella, Chieti.

A Reclining Nude, marble. Private Collection.

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By Ioannis Tzortzakakis

Pope St. Zachary ascended to the papal throne, succeeding Gregory III, probably, on 3 December 741 until his death in 752. He came from a Greek family living in Calabria. He was the last pope of the Byzantine Papacy, yet strongly opposed the iconoclasm (the destruction of religious objects) of Emperor Constantine V Copronymous. Furthermore, he supported the establishment of the Carolingian line in France.

Pope Zachary built the original church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva and restored the Lateran Palace, moving the relic of the head of Saint George to the church of San Giorgio al Velabro.

In addition, in the Council of Rome of 745, he played a key role in the veneration of three archangels, Gabriel, Michael and Raphael, intending to clarify the Church’s teaching on the subject of angels. He is also known for his Greek translation of the Dialogues of Pope St. Gregory I the Great.

Further reading

Jeffrey Richards (1979) Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, 476-752, Routledge & Kegan Paul Books.

This illustration is from The Lives and Times of the Popes by Chevalier Artaud de Montor, New York: The Catholic Publication Society of America, 1911. It was originally published in 1842.

Francesco Solimena known as Abate Ciccio, The Encounter between Rachtis King of the Longobards and Pope Zachary during the Siege of Perugia, 1700 - 1730, oil on canvas, Pinacoteca di Brera.

The church of San Giorgio in Velabro.

Santa Maria sopra Minerva façade by Carlo Maderno.

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

by Rachel Hiser Remmes

The present-day Basilica of San Clemente al Laterano in Rome is a twelfth-century space that stands directly above a fourth-century, titular church, which itself stands above an ancient Roman Mithraic temple. Of the artworks that fill the contemporary building, the twelfth-century apse mosaic is unique among extant medieval, Roman apse mosaics. Centered around an image of Christ on the Cross, framed by Mary and St. John, a paradisiacal environment fills the apse. Verdant acanthus leaves order the space populated by animals, farmers, monks, and rulers, who are arranged without any attention to status or hierarchy, and at the base of the cross two deer drink from the rivers of Paradise.

The vivacious apse program deviates, however, from the fourth-century space below it. This early Christian church underwent several renovations between the fourth and eleventh centuries. In addition to structural supports, frescoes from separate eras and renovation programs were added, working together to unify the space. The last renovation, which occurred at the end of the eleventh century, added four large fresco murals to the church. Three of the four describe the life of St. Clement. The fourth details a scene from the life of St. Alexis, which is found in the nave alongside The Mass of St. Clement, which begins the narration of St. Clement’s Vita. The cycle, then, continues in the atrium with The Miracle of St. Clement and The Translation of St. Clement, with each mural flanking the entrance to the nave.

Crucifixion, Detail, San Clemente Apse, Mosaic, 1100-1128.

Apse, San Clemente, Mosaic, 1100-1128.

Deer drinking from the rivers of Paradise, Detail, San Clemente Apse, Mosaic, 1100-1128.

Peacock, Detail, San Clemente Apse, Mosaic, 1100-1128.

Scribe, Detail, San Clemente Apse, Mosaic, 1100-1128.

The Mass of St. Clement, Lower Church, fresco 1084-1115.

Scene from the Life of St. Alexis, Lower Church, fresco 1084-1115.

The Translation of St. Clement, Lower Church, fresco 1084-1115.

The Miracle of St. Clement, Lower Church, fresco 1084-1115.

Mithraeum, early 3rd cent. C.E.

219 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By Anne Leader

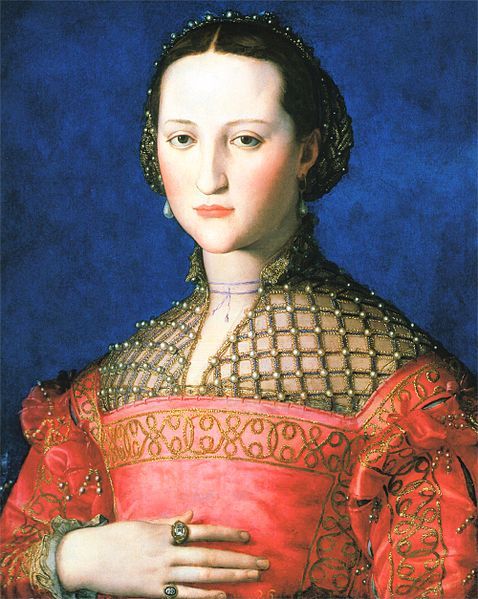

Agnolo Bronzino died in Florence on 23 November 1572, less than a week after his 69th birthday. The leading painter in Florence from the 1530s through the ’60s, Bronzino served the court of Duke Cosimo I de’Medici and produced numerous portraits, allegories, and religious works. The student and adoptive son of Pontormo, Bronzino is associated with the elegance, artifice, and grace of the Mannerist style.

Reference: Janet Cox-Rearick. “Bronzino, Agnolo.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press.<http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T011518>.

Eleonora of Toledo and her Son Giovanni, oil on panel, 1545, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi; photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY

Cosimo I in Armor, oil on canvas, 1543, Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi; Photo credit: Alinari/Art Resource, NY

Portrait of Eleonora di Toledo, 1543, Prague, Národní Galerie

Portrait of an Unknown Man, oil on wood, 1530s, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.16; photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Portrait of Lodovico Capponi, oil on poplar panel, 1550-5, New York, Frick Collection, Henry Clay Frick Bequest, 1915.1.19

Resurrection, oil on canvas, 1552, Florence, Santissima Annunziata

Noli me tangere, oil on wood, 1561, Paris, Musée du Louvre

Venus, Cupid and Time (Allegory of Lust), oil on panel, 1540-45, London, National Gallery

Martyrdom of St. Lawrence, fresco, 1569 (Florence, San Lorenzo)

246 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Italian condottiere (mercenary soldier) Bartolomeo Colleoni died on 2 November 1475 near Bergamo. Perhaps best known through his magnificent equestrian portrait by Andrea del Verrocchio, Colleoni had an esteemed military career, serving Naples, Florence, Milan, and Venice in the 1430s and 1440s. In 1455 he was named General Captain for Venice, and it was here that his bronze portrait was erected in accordance with his testament. Colleoni wanted his statue to stand in Piazza San Marco, but it was placed instead in the Campo di Santi Giovanni e Paolo. Created by Verrocchio in the style of ancient imperial monuments, particularly the famed statue of Marcus Aurelius, which stood at the time in the piazza of St. John Lateran in Rome. (It was moved to the Capitoline in the middle of the sixteenth century as the focal point of Michelantelo’s Piazza del Campidoglio.)

While equestrian portraits were reserved for emperors and rulers in the ancient world and Middle Ages, by the Renaissance the motif was used to celebrate military captains and soldiers. Verrocchio imbued his statue with great energy, as Colleoni’s horse strides forward and turns into space. The rider himself looks alert and strong, his watchful gaze protecting the citizens of Venice who passed underneath his feet.

Colleoni’s military exploits allowed him to amass great wealth, which he used to commission numerous artistic projects. In addition to leaving a bequest for a commemorative statue in Venice, Colleoni erected a splendid burial chapel in his hometown of Bergamo.

Bertrand Jestaz. “Colleoni, Bartolomeo.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. <http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T018600>.

Andrea del Verrocchio, Equestrian Portrait of Bartolomeo Colleoni, 1483-94. Bronze. Venice, Campo di SS. Giovanni e Paolo.

Sisto and Siry of Nuremburg, Equestrian Portrait of Bartolomeo Colleoni, 1501. Bergamo, Colleoni Chapel

Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, 176-80 CE. Gilded bronze. Rome, Capitoline Museum

Giovanni Antonio Amadeo, Colleoni Chapel, 1470-6. Bergamo

Colleoni Coat of Arms, marble. Bergamo, Colleoni Chapel

Tomb of Bartolomeo Colleoni, after 1476. Bergamo, Colleoni Chapel

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

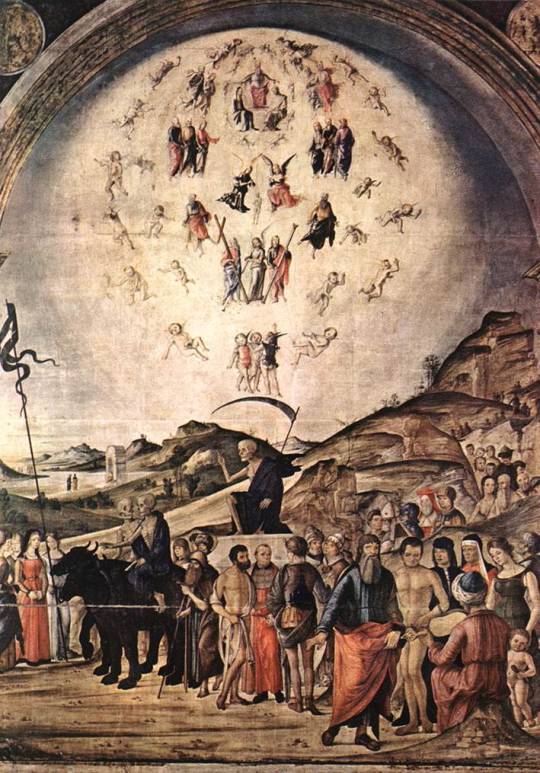

Hallowmas and Beyond: The Inevitability of Death in Medieval and Early Modern Italian Art

Hallowmas season is a Western Christian religious festival that encompasses All Saints’ Eve (Halloween), All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. During this triduum, which is celebrated between 31 October and 2 November each year, the living faithful of the Roman Catholic Church are obliged to honour the dead, including the saints in heaven and those souls in purgatory. The feast also serves to remind the living that they can be saved or damned and that heaven, hell and purgatory exist.

Outside of the Hallowmas season, inhabitants of the Italian Peninsula during the Medieval and Early Modern periods would have been regularly reminded that death was certain and omnipresent. Apocalyptic preaching was popular in various regions and throughout the ages, with participants such as Salimbene of Parma, Bernardino of Siena, Girolamo Savonarola, Giovanni Dominici and Francesco da Montepulciano warning that one could not escape God’s judgement both in this life and the next. Bernardino of Siena for example, spoke of God’s “fearful judgement” and the “boils’ and “scourges” that would blight individuals and entire populations as a result of their vanities and other sinful activities.

As if to affirm these spoken revelations, the harsh realities of Medieval and Renaissance life would likely have worked to confirm the faithful’s belief in Divine retribution. The horror of war, regular outbreaks of plague, generally high mortality rates and the grisly reportage of violent and unexplained events (such as crop failure, suicides, murders, human and animal birth defects) would ostensibly have added to the apocalyptic climate, as would the popularity of death-centric literature, such as Petrarch’s Triumph of Death.

In post-Tridentine Europe, the ongoing discord between the various forms of Protestantism and Counter-Reformation Catholicism guaranteed that the apocalyptic mood of earlier epochs would continue during the sixteenth century.

It is unsurprising then, that visual representations based on biblical sources, church dogma, death-centric popular literature, historical events and hard fact emerged as recurrent themes in Medieval and Early Modern Italian art. Genres and sub-genres including The Triumph of Death, allegories of death, the Momento Mori and the Danza Macabra, all serving as perpetual reminders that death will come to us all - any day - any place - anytime - and the faithful should consider its inevitability not just at Hallowmas, but always.

References: The Revelation of Saint John, King James Version of the Bible, 1611.

Andrew Cunningham and Ole Peter Grell, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Religion, War, Famine and Death in Reformation Europe, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Luca Landucci, A Florentine Diary from 1450-1516 by Luca Landucci Continued by an Anonymous Writer ‘Till 1542 with Notes by Iodoco del Badia, trans. Alice de Rosen Jervis, London, J. M. Dent and Sons, 1927.

John M. McManamon, “Renaissance Preaching: Theory and Practice. A Holy Thursday Sermon of Aurelio Brandolini.” In Medieval and Renaissance Studies, vol. 10, pp. 355-374.

Ottavia Niccoli, Prophecy and People in Renaissance Italy, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane, New Jersey, Princeton University Press, 1990.

Francesco Petrarch, Triumphus Mortis. © 199-2006, Peter Sadlon. Available at http://petrarch.petersadlon.com/read_trionfi.html?page=III-I.en

Girolamo Savonarola, Selected Writings of Girolamo Savonarola: Religion and Politics, 1490-1498, London, Yale University Press, 2006.

Bernardino of Siena, Saint Bernardine of Siena: Sermons, ed. Don Nazerino Orlandi, trans. Helen Josephine Robins, Siena, Tipografica Sociale, 1920.

Ingrid Volser, The Theme of Death in Italian Art: The Triumph of Death, MA Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, 2001.

Images: Lorenzo Costa, The Triumph of Death, 1490, fresco, San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Andrea di Cione (Orcagna), Detail from The Triumph of Death, 14th century, fresco, Santa Croce, Florence, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Giacomo Borlone de Burchis, The Triumph of Death, 15th century, fresco, Oratorio dei Disciplini, Clusone, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Giacomo Borlone de Burchis, Dance Macabre, 15th century, fresco, Oratorio dei Disciplini, Clusone, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Unknown, The Triumph of Death, 1446, fresco, Palazzo Abetellis, Palermo, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Gaetano Giulio Zumbo, A Damned Soul, c.1700, relief, wax on painted copper, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Copyright: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2017.

Giovanni Bernardino Azzolino, A Soul at Death, 1620-1630, relief, coloured wax on painted glass in deep stained and gilt box frame, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Copyright: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2017.

Giovanni Bernardino Azzolino, A Soul in Purgatory, 1620-1630, coloured wax on painted glass in deep stained and gilt box frame, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Copyright: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2017.

Caterina de Julianis, Time and Death, before 1727, coloured and moulded wax, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2017.

Attr. Apollonio di Giovanni, The Triumph of Death, 15th century, tempera and ink on parchment, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Italy. Wikimedia Commons.

Stefano della Bella, Death on the Battlefield, c. 1650–64, etching; proof state retouched with graphite and pen and brown ink, sheet (trimmed): 7 ½ × 11 ¾ in. (19.1 × 29.8 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928, and The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959, by Exchange. Public domain.

Posted by Samantha Hughes-Johnson.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just In Time For Halloween... Cortenova’s “House of Witches.”

In the hamet of Cortenova, within the forested Province of Lecco, Lombardy, sits a nineteenth-century mansion variously known as “The House of Witches,” “The Ghost House” or “The Red House.” In the spirit of Eclecticism, the building’s architectural heritage can be found in Baroque and Eastern forms of the discipline.

The house was built between 1854 and 1857 by Count Felix de Vecchi and was meant to be his family’s residence during the halcyon days of summer. Vecchi employed Alessandro Sidoli as his architect although he did not see the project brought to fruition, as he died around one year before it was completed. In retrospect, this event could be where the rumours of bad luck and hauntings connected to the property began.

According to gossip and legend, in 1862 Vecchi, who had been out, returned to the property to find his wife brutally murdered and his daughter missing. The latter was never found and apparently the count cold not live with this and went on to take his own life. Accordingly, the property passed directly to the count’s brother, Biagio, who lived on the estate with his family until around the time of World War II. During the 1920s, it was said that Aleister Crowley, the self-proclaimed prophet and controversial occultist, had stayed there, which fuelled the fires relating to gossip concerning witchcraft, sex rites and ritual sacrifice.

Beyond the remians of the house, which in itself is a verifiable architectural primary source, exactly which parts of the story are urban legend and what sections are fact remains unclear. What is certain however, is that when you look upon these images of a home now abandoned and vandalised… today, of all days, when the veil between the living and the dead is at its most thin, you may feel a little shiver as you sip your pumpkin spiced latte. Not to worry though. Stoke up the fire, draw the drapes and try to convince yourself that you DID NOT just hear the tinkling keys of a grand piano…

Images: Image 1 Courtesy of NSS Magazine.

Images 2 - 7 courtesy of Matteo Rubboli and Vanilla Magazine.

Image 8 Wikimedia Commons.

References: “Villa de Vecchi,” Atlas Obscura.

“Is This The Creepiest Villa In The World,” Daily Mail, 17 October, 2018.

Posted by Samantha Hughes-Johnson.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Martina Bollini

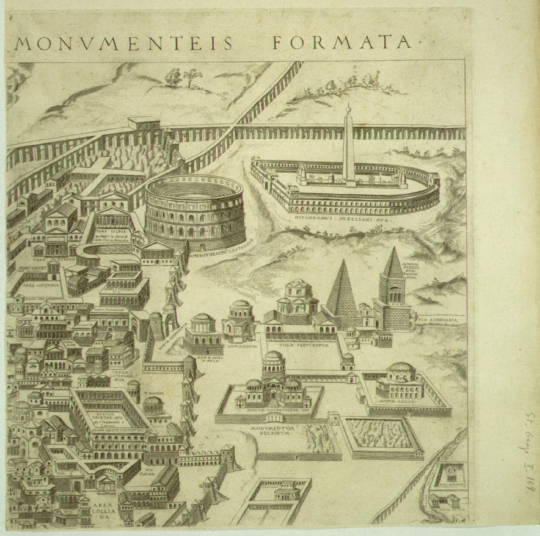

Architect, painter, landscaper, and antiquarian Pirro Ligorio died on 26 October 1583. He was born in Naples between 1512 and 1513 from a patrician family. Little is known about his early formation. His contemporary Giorgio Vasari did not include an account of Ligorio in his Lives, most likely because of professional rivalry. What we know is based on Giovanni Baglione’s Lives, published in 1642. According to Baglione, in 1534 Ligorio was in Rome to work as a painter. In the Eternal City the artist developed his interest in classical antiquities. Later, he worked on two very detailed encyclopedias of classical artifacts, which he was never able to publish because of their massive size. He did publish a series of maps, including his famous map of ancient Rome (Antiquae Urbis Imago), in 1561.

In 1549 Ligorio became archeologist for Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este. From then on, his work was characterized by a more strict intellectual approach. For the cardinal, Ligorio devised the iconographic program for the gardens of Villa d’Este at Tivoli, greatly influenced by the nearby Villa Adriana.

Ligorio then moved to the papal court in 1558. For pope Pius IV he designed the Casina Pio IV in the Vatican gardens, considered one of his masterworks. In 1564 Ligorio was appointed chief architect of St. Peter’s. However, his fortune declined with the next pope, Pius V (1566-1572) who, disapproving the artist’s passion for classical antiquity, dismissed him.

In 1568 Ligorio accepted the offer of a post as Ducal Antiquary at the court of Alfonso II d’Este in Ferrara. Following the 1570 earthquake that devastated the city, he conducted a series of engineering studies, with a striking modern approach.

Reference: “Ligorio, Pirro”, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 65 (2005).

Further reading: David R. Coffin, Pirro Ligorio. The Renaissance Artist, Architect, and Antiquarian, University Park, PA, 2004.

Antiquae Imago Urbis (detail), Lossi reprint, 1773.

Sketches after the Antique: Bacchic Revels; Neptune in His Chariot, c. 1535, Black chalk, with pen and brown ink, on ivory laid paper, laid down on cream laid paper, Art Institute, Chicago.

Villa d’Este – photo of the author.

Casina Pio IV, 1558-1561, Vatican City.

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Martina Bollini

On this day (26 October) in 1640, Pietro Tacca died in Florence.

The chief pupil of Giambologna, he worked for the Medici Grandukes of Tuscany as court sculptor. To celebrate Ferdinand I’s triumphant victory against the Barbary corsairs, Tacca made the monument of Four Moors in chains for the port city of Livorno. The group was placed at the foot of Giovanni Bandini’s marble portrait of the Duke.

Tacca’s sculptures also decorate two iconic public spaces in Florence: piazza Santissima Annunziata and the Loggia of the Mercato Nuovo (although here the original statue of the Porcellino has been replaced with a copy).

His service for the Medici included the execution of the tombs of Ferdinando I and Cosimo II. The cenotaphs are located in the Cappella dei Principi in the church of San Lorenzo, traditional burial place of the Florentine family.

Tacca worked for other European monarchs too, creating equestrian monuments such as the colossal statue of Philip IV of Spain, his last major project (1634-40). The statue, originally designed for the garden of the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid, is now dominating the Plaza de Oriente.

Four Moors, 1623-26, bronze, Piazza Micheli, Livorno.

Fountain, ca. 1629, bronze, Piazza Santissima Annunziata, Florence.

Il Porcellino, 1621-34, bronze, Museo Bardini, Florence.

Detail from the Monument to Ferdinando I de Medici, 1626-1632, Cappella dei Principi, Basilica di San Lorenzo, Florence. Photo Credit: The Courtauld Gallery

Equestrian monument to Philip IV, 1634-40, bronze, Plaza de Oriente, Madrid.

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By Martina Bollini

Today, 24 October, is the feast day of Saint Raphael the Archangel. Raphael is one of the seven Archangels, and one of the only three mentioned by name in the Bible, together with Gabriel and Michael (Luke 1:9–26; Jude 1:9).

Raphael only appears in the Biblical Book of Tobit, as the travelling companion of Tobias, Tobit’s son. He initially presents himself as “Azarias the son of the great Ananias”. Back from his journey with Tobias (sent to Media to collect a debt), Raphael delivers Sarah, Tobias’ future wife, from the demon Asmodeus, and heals the blind Tobit. His true identity is then revealed and he makes himself known as “the angel Raphael, one of the seven, who stand before the Lord” (Tobit 12:15). In virtue of his healing powers, Saint Raphael is also believed to be the archangel who healed the multitude of infirm at the pool of Bethesda (John 5:1-4).

St. Raphael is the patron saint of travelers, and as such he is depicted holding a staff. Often, he is represented with Tobias, holding or standing on a fish, which alludes to the healing of Tobit with a fish’s gall.

Francesco Botticini, The Three Archangels and Tobias, 1470, tempera on wood, Florence, Uffizi Gallery.

Pietro Perugino, The Archangel Raphael with Tobias, 1496-1500, oil with some egg tempera on poplar, London, National Gallery.

Altobello Melone, Tobias and the Angel, early 1520s, oil on panel, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum.

Domenichino, Landscape with Tobias laying hold of the Fish, 1610-13, oil on copper, London, National Gallery.

Francesco and Gianantonio Guardi, The healing of Tobit, c. 1750, oil on canvas, Venice, Church of the Arcangelo Raffaele.

101 notes

·

View notes

Photo

By Jennifer D. Webb

Architect Bernardo Vittone died on October19th, 1770. Over the course of his career he worked in small towns in the region of his birth. In 1732, he spent a year in Rome studying at the Accademia di San Luca. Immediately after his return to Turin he collaborated with the Theatines on an edition of Guarino Guarini’s Architettura Civile (1737). This undertaking familiarized Vittone with Guarini’s ideas at the same time that he could experience first-hand the near-complete buildings of another great architect, Filippo Juvarra. Rudolf Wittkower notes that it was Vittone who “reconciled the manner of Guarini with that of Juvarra.” (47)

While Vittone completed both secular and ecclesiastical buildings, it is for the latter that he is best known. His first project, the Sanctuary at Vallinotto (near Carignano) was begun in 1738 and typifies the architect’s preference for centralized planning. Wittkower notes that “the interior surpasses that of the exterior” and that the hexagonal-plan with segmented chapels is “a climax right at the beginning.” (48)

Reference: Wittkower, Rudolf. Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750. (1999)

Bernardo Vittone, Sanctuary, Vallinotto (1738-39) (photo credit: K. Weise)

Further Reading: Oliver Bernier, “Turin’s Baroque Splendors.” The New York Times (1990); Guarino Guarini, Architettura Civile. London: Forgotten Books, 2018.

4 notes

·

View notes