Quote

魄依鉤樣小,

扇逐漢機團。

細影將圓質,

人間幾處看。

My soul, conforming to this crescent, dwindles

and flying, now chases a gathering of stars.

Its fine light form, against the darkness, fills again

and, from all this world of men, its circle can be seen.

Moon (月) by Xue Tao (薛濤). Tang Dynasty.

Moon is a spontaneous poem about characters embracing light and darkness. Xue Tao (薛濤), courtesy name Hongdu (洪度/宏度), is one of the most well-known poets of the Tang dynasty. She was the daughter of a government official in Chang’an. After her father transferred to Chengdu, she was later registered as a courtesan and entertainer there. Famous for her poetic talent and wit, she attracted the attention of Wei Gao, the military governor of Xichuan Circuit, and he made her his official hostess. About 100 of her poems showcasing her lively intelligence and literary skill are known to this day, more than any other Tang dynasty woman poet. The Venusian crater, Hsueh T’ao, was named after her.

Follow sinθ magazine for more daily posts about Sino arts and culture.

(via sinethetamagazine)

211 notes

·

View notes

Text

sansarika:

Kshama turned her head to look at Yaling with subdued surprise. “I do not wish to unload what is in my my heart onto you, Ya. Not when you have gone through so much trouble just to see me as I am… or as I should be. I am nothing but worried, and I do not want that to worry you too.”

Misty-eyed, Kshama moved Ya’s hand off her shoulder to hold it in her own, kissing the other woman’s knuckles tenderly before placing her hand back in her lap for her. “I am sorry that I have brought my sorrow with me, and I regret not seeing you when my heart was happier.”

After a pause, a smile began to play on her face — she picked up a chopstick on their table and skewered an apricot slice on it before raising it to Yaling’s lips as if she was going to feed her. “But I have learned that sorrow can be drowned in indulgence. Open up!”

“Oh, Kshama...”

Before she could even argue, Kshama was already sticking food into her mouth. “I am not a baby!” she laughed, but Yaling opened her mouth anyway. She turned Kshama’s own distraction on her, picking up the little cakes and placing them between Kshama’s pretty lips. “How does that make you feel, hm?”

If she had to lie in wait to extract the news from Kshama, then she would play the part.

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Traditional Chinese fashion from 1980s dramas.

339 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Magical girl Nyo!China commission for @rainbowcolouredafternoon 💖

I haven’t tried to design any fantasy clothes in forever… :;(∩´﹏`∩);:

>Commission me here!

313 notes

·

View notes

Photo

costumes per historical period: imperial china: five dynasties and ten kingdoms, song dynasty (907-1279)

835 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ref for my OC, but it’s too beautiful to not spread the love

Lips make up in Tang Dynasty style

748 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lian Zhang (Chinese, b. 1984, Hangzhou, China) - Elsewhere, 2013 Paintings: Oil on Board

611 notes

·

View notes

Text

sansarika:

“Can you blame me for being clueless, Ya? I hardly know where to start!” A laugh in her voice, Kshama watched Yaling assemble her plate and did the same with her own. “And I do not want to embarrass myself. I remember my first time leaving my place — apparently not everyone everywhere eats with their bare hands.”

She subconsciously inched closer to the other woman where they sat before looking up when she was addressed. “Tea? Any kind of tea is good tea. Ginger, maybe? Oh, no, we had that earlier.” A smile. “You are the hostess, yes? You decide.”

“We use chopsticks to serve and cook our food because we want to be far away from it, I suppose,” Yaling laughed.

Since Kshama had no preference, Yaling picked the green tea. It was a simple staple, and everyone could agree on it. They could have fancier tea cakes for dessert.

“Settle in,” she instructed softly, laying a gentle hand on the other’s shoulder. “I want you to unload your heart at the same time you fill your stomach. What has been happening at home?”

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know what sort of material was used in traditional Chinese makeup? Did they have similar issues with toxic makeup products as Europe? Sorry, historical makeup is just so fascinating to me!

Hi, thanks for the question!

Makeup in ancient China was created by boiling and fermenting ingredients such as plants, animal fats, and spices.

Facial powder (foundation) was one of the most rudimentary forms of makeup that was made by grinding fine rice. Another form of powder was made using lead, which despite its toxicity, was coveted for its skin-whitening properties.

Rouge, powder used to color the lips or cheeks, was made from the extracted juice of leaves from red and blue flowers. Ingredients such as bovine pulp and pig pancreas were also known to have been added, to make the product denser.

Lip makeup was made from the raw material vermilion, a scarlet pigment originally made from the powdered mineral cinnabar. Eventually mineral wax and animal fat were added, making the vermilion water-proof with a strong adhesive force. In order to add fragrance, raw materials such as ageratum and clove, and artificial flavors were added.

To paint their eyebrows, women used the soot derived from burning willow branches. Another type of eyebrow makeup was made using dai, a blue mineral that was grinded into powder and mixed with water.

From the Tang Dynasty and onwards, huadian, a decorative element located on the forehead, came into vogue. Huadian was often created using gold or silver foil, paper, fish scales, or even dragonfly wings (or just painted on). I have a detailed post about huadian here.

Finally, nail polish originated in China (!!) and dates back to 3000 BC. To paint their nails, the ancient Chinese used a mixture of egg whites, gelatin, beeswax, gum Arabic, alum, and flower petals.

Hope this helps!

Sources: 1, 2, 3

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Traditional Chinese hanfu in Ming dynasty style by 李哥哥要当红军咕唧

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Swaying with Every Step: an Analysis of the Chinese Hair Ornament Buyao

Translation of original post here

Historically, buyao (步摇), the step-swayer hairpin, has always been the favorite jewel of many a Chinese woman’s vanity closet, and even migrated across the sea in the form of Bira-bira kanzashi (びらびら簪) Yet when studying hanfu, one finds that there are two very different sorts of buyao. One stands upright and sprouts out of a base like the bough of a tree, the other dangles a strand of beads from a single straight pin. This division comes from ancient people confusing two separate types of hair ornaments for each other. Of the two, the dangling beads variety of buyao has proved to be more popular after the Song Dynasty.

A buyao is a type of hair ornament that originated with the northern steppe nomads, and spread into Northern China after repeated contact between the two peoples. While the steppe nomads led a harsher and less advanced life than the sedentary Chinese, they possessed amazing metalworking technologies and produced a plethora of delicate, beautiful ornaments, among them the buyao. Song Yu, one of the greatest poets of the Warring State Period, writes in his Ode on Satire “The master’s’ daughter, cloaked in the splendor of sun, wrapped in a green cloud-like feather cloak, and moreover dressed in a tunic of white gauze, with buyao decorated with hanging pearls…” The Shiming Dictionary, compiled by Liu Xi in the final years of the Eastern Han, defines the buyao ornament as: “Buyao, an ornament with pearls dangling down, which sways with every step.” A Xiongnu crown excavated during the Han Dynasty shows a golden band topped with a small hawk-shaped ornament, which might have bobbed up and down as the wearer walked. In this, the decorative purposes resemble that of Scythian crowns.

Xiongnu crown

Bactrian Tomb VI gold crown

Around the same time, during the Eastern Han Dynasty, the buyao ornament rose in prominence to become part of a noblewoman’s ceremonial regalia. In the Book of the Later Han, the section ‘Travel and Dress’ records the Empress’ regalia for making offerings at the ancestral temple as: “Bejeweled in buyao and zan-er. The buyao has a peaked base constructed of gold, connects white pearl pendants in the shape of intersecting osmanthus branches, and features one jue and nine flowers, along with the six beasts of, bear, tiger, red bruin, heavenly hart, evil-repelling chimera, and the Great Divine Horned Beast of Nanshan, which are the ‘In her headdress, and the cross-pins, with their six jewels’ mentioned in the Classic of Poetry. The jue and the various beasts all have their fur and feathers constructed from jadeite and their base constructed from gold, and are further surrounded with white dang beads, with clusters of flowers constructed from jadeite.” A buyao has a golden peak base. The basic shape of the base is rectangular, but can also be peaked like the golden badge of the Emperor’s crown. There are also buyao which have bases shaped like horses and oxen and other animals. Above the base, white pearls are strung into vertical branches like those of the osmanthus tree. On the branches perch one jue and nine flower decorations. A “jue” is a Chinese word denoting “nobility”. This character is interchangeable with the character for “pheasant”, having evolved out of the use of pheasant-shaped crowns by nobility of neolithic times. When used to refer to jewelry, it denotes a bird-shaped ornament. A “jue”, then, is a jeweled bird perched upon the branches of the buyao. Also perched on the branches are six auspicious beasts, imitating the “cross-pins with their six jewels” mentioned in the Classic of Poetry. A tiger is a tiger; a bear is the Asian black bear; a red bruin is a brown bear; a heavenly hart is a deer with a single horn and a long tail, which serves as a companion to the chimera; a chimera, also called pixiu, is a beast with the head of a dragon and the body of a tiger, but short and squat; a Great Divine Horned Beast of Nanshan is a divine bull spirit said to reside in the trunks of ancient trees. The bird and all the beasts have a golden base, and have jadeite inlays forming feathers and fur. They are surrounded by white beads in the shape of double-headed, narrow-waisted drums. The nine clusters of flowers are also constructed from jadeite.

Han Dynasty gold bird and flower ornaments

The size and prominence of the buyao increased come the Jin Dynasty, and the scale became eight bird decorations and nine clusters of flowers. Also added to the Empress’ regalia were twelve huadian hairpins. With the advent of Xianbei rule during the Sixteen Kingdoms and the Northern and Southern Dynasties, buyao gained popularity with the upper classes. Not only was it worn by women, but also by men. One group of Xianbei, due to their custom of wearing golden buyao, took the name of the ornament as their surname, becoming the Murong Xianbei.

Various buyao of the Northern and Southern Dynasties

Northern Yan gold Murong buyao crown

Depictions of Jin Dynasty and Northern Wei women wearing buyao

The ‘Etiquette’ section of the Book of Song from the Northern and Southern Dynasties records: “According to the regulations of the Han, the Empress Dowager’s robe for entering the ancestral temple and offering sacrifices would have a navy top and a black bottom. The robe for the Silkworm Ceremony would have a blue top and a white bottom. Both are forms of shenyi, which means one continuous garment. Her hair would be jeweled with a jianmao band. According to the regulations of the Han, The Empress’ robes for entering the ancestral temple and offering sacrifices would have a navy top and a black bottom. The robes for the Silkworm ceremony would have a blue top and a white bottom. Her hair would be jewelled with a false coiffure wig, and a buyao featuring eight pheasants and nine flowers and decorated with jadeite. The Jin Dynasty annotations of the ‘Silkworm Ceremony’ chapter note that the Empress has twelve huadian, buyao, and a great-handed coiffure wig; and wears a pure blue robe with jade waist-pendant and train. In the current era, the Empress wears a long swallow-tail hem robe that has been given the name of the Great Pheasant robe.” The “Etiquette” section of the Book of Sui records the regalia of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, with the Empress’ regalia from the Liang and the Chen Dynasties in the south being: “When the Empress visited the ancestral temple, she wore the long robe with apron which also serves as her wedding gown, given of the Great Pheasant robe. Its top is black and its bottom is black. The robe for the Silkworm Ceremony, on the other hand, has a blue top and a white bottom. Both are forms of shenyi. The borders of the collars and sleeves would be obscured and hemmed with strips of green. Her hair would be jewelled with a false coiffure wig; buyao, which is also called the beaded pine; and zan-er. The buyao has a peaked base constructed of gold, connects white pearl pendants in the shape of intersecting osmanthus branches, and features eight jue and nine flowers, along with the six beasts of, bear, tiger, red bruin, heavenly hart, evil-repelling chimera, and the Great Divine Horned Beast of Nanshan. All the birds and beasts are adorned with jadeite. The jade waist-pendant and the train are the same as the Emperor’s travelling regalia.” Meanwhile, in the North, the Northern Wei Dynasty’s regalia were: “The Empress’ seal, train, and jade waist-pendant are the same as the Emperor’s travelling regalia. Her regalia are the false coiffure wig, buyao, twelve huadian, and the eight pheasants and nine flowers. When she assists in sacrifices in the Court, she wears the Great Pheasant robe; when she accompanies the King on sacrifices outside city walls, she wears the Lesser Pheasant robe; when she attends banquets, she wears the Courtyard Pheasant robe; when she hosts the Silkworm Ceremony, she wears the Yellow Mulberry robe; when she greets the Emperor, she wears the Plain White robe; and in private, she wears the Bordered Robe. The six robes all require an apron and trailing colored sashes. The Empress Dowager’s and the Empress’ great seals are constructed of white jade, with a perimeter of one cun and two fen. They are decorated with a wyrm handle and they carry an inscription of the holder’s titles. The great seals were not widely used, and instead the Empress Dowager used Captain of the Guard’s seal which carried the name of her palace of residence, and the Empress used the seal of the Chief Eunuch. The Inner and Outer Titled Women of rank five and above have their hair jeweled with a false coiffure wig and their rank expressed through the number of huadian they wear.” The Northern Zhou Dynasty in turn had: “The Empress’ flower ornaments are arranged in twelve clusters. The wives of the barons decrease one cluster of flowers for each number of their rank. Below the Three Consorts and the wives of the Three Excellencies again decrease one cluster of flowers for each number of their rank. Women of the first rank wear three clusters of flowers fewer than the Empress.” During the Sui Dynasty, the buyao with flower clusters and the huadian of the Northern Dynasties were combined into the flower crown, which then in turn evolved into the Phoenix Crown.

Early Tang Dynasty Empress Xiao Crown

All of these buyao, without exception, refer to branched buyao with a base. There are no records of buyao with dangling beads. The people of the Later Han Dynasty compared the Empress’ ceremonial attire to the ceremonial headdresses found in the Rites of Zhou. From their annotations, one can see their concept of a buyao ornament. In “Book 1: Heavenly Minister Great Administrator” of Rites of Zhou, the section “Service of the Chief Jeweler” records: “Zhuishi, the Chief Jeweler: He is charged with overseeing the headdresses of the Queen, which are the tiaras, the wigs, the hairpieces, the caps, the crosspins and the hairsticks. These ornaments serve as the headdresses of the Nine Companions as well as the Outer and Inner Titled Women so that they might attend sacrifices or receive guests. In the event of a funeral, he shall bear the same responsibilities over the hairsticks and mourning ties.” Annotations from the Later Han Dynasty scholar Zheng Xuan in Rites of Zhou, Annotated and Explicated state: “Zhui: a type of cap. The ‘Capping Rites for Common Officers’ section of Etiquette and Ceremonial records: ‘Weimo, the name during Zhou. Zhangfu, the name during Shang. Muzhui, the name used by the lords of the Xia.’ The Zhuishi is thus the master of caps and crowns, and so too does he oversee the headdresses of the queen. The item of Fu or Tiara: a woman’s headdress. ‘A Summary Account of Sacrifices’ from the Book of Rites states: ‘The ruler, in yellow-black robes and square-topped crown, stood at the top of the steps on the east, while his wife in her Tiara Headdress and Great Pheasant robe, stood in the chamber on the east.’ The Heng, or Crosspins, are items that fasten the cap in place. The Spring and Autumn Chronicle lists ‘crosspins, ear tassels, fastening strings, and crown coverings—all these illustrate his observance of the statutory measures.’ All refer to the fact that a Fu tiara references the word ‘covering’, which has the same sound, and therefore, the tiara is an ornament that covers the head. Its modern derivation is the buyao. It is worn when accompanying the King to sacrifices. The item of Bian or Wig: used to coif the hair, its modern derivation is the false coiffure wig. It is worn when attending the Silkworm Ceremony. The item of Ci, or Hairpiece: used to adjust the length of the hair, its other name is the false lock. It is worn when attending upon the King. When the Queen is in private, she but fastens her hair with streamers and a hairstick. The Classic of Poetry has the line: ‘Engraved and chiselled are the ornaments.’ The Queen’s crosspins and hairsticks are all made of jade. Only sacrificial regalia includes crosspins. They hang to the two sides of the tiara above the ears, and below each of them jade plugs dangle from ear tassels. The lines ‘How rich and splendid is her pheasant-figured robe! Her black hair in masses like clouds, no false locks does she descend to. There are her ear-plugs of jade…’ from the Classic of Poetry refer to these ornaments. The item of Ji, or Hairstick: used to curl up the hair. Outer and Inner Titled Women dressed in the Yellow Mulberry robe wear wigs, while those dressed in the black Bordered Robe wear hairpieces. When the Outer and Inner Titled women are not assisting the Queen in rituals of sacrifices or greeting guests, their regalia goes down a rank back in their own homes. For example, ‘Then the wife of the host builds up her hair with false locks. She wears the Bordered Robe with wide flowing sleeves.’ from ‘Rites of the Secondary Pen Victim Offering’, and ‘The wife of the Master of Ceremonies, with her hair wrapped in streamers, and wearing dark Everyday Robes’ from ‘Rites of of the Single Victim Food Offering’, from Etiquette and Ceremonial. In the section of ‘Nuptial Rites for a Common Officer,’ the bride’s hairpiece and black Bordered Robe are an exception to clothing restrictions allowed for celebratory costumes. The groom wears a nobleman’s square-topped cap to greet her. Wide flowing sleeves refer to the sleeves of the Bordered Robe. The wives of the great barons dress in the same clothes as the queen in their own fiefs.”

By the time of the Tang Dynasty, the Han Dynasty annotations had become too esoteric, so the Tang Dynasty scholar Jia Gongyan expanded upon the annotations with: “The line ‘He is charged with overseeing the headdresses of the Queen’ draws a parallel between the Chief Jeweler and the Master Haberdasher of Ministry of Summer, who oversees the headdresses of the men. The headdresses of the women are the tiara, the wig, and the hairpiece. In the line “zhui bonnet, crosspin, and hairstick”, “zhui” actually means to carve jade. Thus, it means “crafting jade into cross-pins and hairsticks.” In the line “These ornaments serve as the headdresses of the Nine Companions as well as the Outer and Inner Titled Women”, the phrase “as well as” mean the same as when used to describe the duties of the Director of the Clothing of the Inner Quarters. Both connote the difference of rank between women listed. The Hereditary Titled Women are not listed under the Nine Companions.. Therefore, in abbreviated list given by the text, Outer Titled Women refer to the wives of the Three Excellencies and the wives of the great officers, while Inner Titled women refer only to the Royal Concubines.The line ‘so that they might attend sacrifices or receive guests’ also refers to their duty to assist the queen during rituals. According to the annotations from Minister of Finance Zheng, the line ‘Zhui: a type of cap’ quotes ‘Capping Rites for Common Officers’ as proof because of the explanation found in ‘Capping Rites’ about the Muzhui cap used by the lords of Xia. In the line ‘The Zhuishi is thus the master of caps and crowns, and so too does he oversee the headdresses of the queen”, Minister Zheng implies that the Chief Jeweller oversees the construction of the caps and crowns, while the Master Haberdasher oversees their design, similar to how while the Tailor is responsible for the sewing of the robes, there are also the offices of the Director of Clothing and Director of the Clothing of the Inner Quarters; and, therefore, there are two officers in charge of the men’s headwear. Yet contrary to Minister Zheng’s analysis, if the Chief Jeweller was also charged with overseeing the men’s headwear, then his duties would be described in the same manner as those of the Cordwainer: ‘he is charged overseeing the footwear of the King and Queen,’ with the King and Queen mentioned separately. As the description does not include the King, it is apparent that the two offices are not both responsible for the King’s headgear, and instead, the Chief Jeweller only oversees the headdresses of the Queen and the women ranked under her. The quote from ‘A Summary Account of Sacrifices’ proves that a tiara is an item of jewelry. The quote from the Spring and Autumn Chronicle is cited from the remonstration of Zang Aibo during the second year of Duke Huan. When he lists the ‘crosspins, ear tassels, fastening strings, and crown coverings’, he refers to crosspins being used by men. Using this as evidence Minister Zheng implies that both men and women use crosspins, and both their headgear would be in the charge of the Master Jeweller. Yet after this, Minister Zheng does not involve any men nor their regalia in his annotations. ‘All refer to the fact that a Fu tiara references the word ‘covering’, which has the same sound, and therefore, the tiara is an ornament that covers the head.’ The word of “fu” means “secondary” or “to assist” and thus is also used to mean “to cover.” Minister Zheng states ‘Its modern derivation is the buyao’. The buyao of the Han Dynasty refers to an ornament worn on the head that sways with the wearer’s step. He must have come to this conclusion by observing the modern regalia and using it as a basis to reconstruct the ancient version. Much time has elapsed between the Han Dynasty and now, and it is impossible to know whether or not he was right. The Classic of Poetry mentions ‘In her headdress, and the cross-pins, with their six jewels’, referring to six items added to the tiara, yet what items remains unknown. As a result, Minister Zheng’s annotations of the Classic of Poetry state, ‘A tiara is a hairstick with added items. I have not found out the design used by the ancients’. In the line ‘It is worn when accompanying the King to sacrifices’, Minister Zheng implies that the Three Pheasant Robes all include a tiara as a headdress. The sacrifices include offerings to the ancient kings, the ancient princes, and the multitude of offerings to lesser divinities, which are thus all encapsulated in the word ‘sacrifices’. In the line ‘the item of Bian or Wig: used to coif the hair’, Minister Zheng again uses the typical meaning of the word ‘bian’, which means to arrange, to interpret the function of the headdress. The line ‘ its modern derivation is the false coiffure wig’ is again Minister Zheng extrapolating the ancient version from contemporary wigs, and on this also, too much time has elapsed to know whether or not he was right. ‘It is worn when attending the Silkworm Ceremony’. Previous annotations state that the Yellow Mulberry robe is worn to the Silkworm Ceremony, while later annotations along with Minister Zheng’s Answers state that the headdress for the Plain White robe is the false coiffure; therefore, only mentioning the Yellow Mulberry robe being worn to the Silkworm ceremony, while not mentioning the Plain White robe is an abbreviation. The wig is also worn with the Plain White Robe. The line ‘the item of Ci, or Hairpiece: used to adjust the length of the hair’ is also a literal interpretation. Since the headdress is called ‘ci’, and ‘ci’ means ‘to measure’, the headdress is understood to be an item that adjusts the length of the hair. The line ‘its other name is the false lock clarifies that the ‘false locks’ from ‘Rites of the Secondary Pen Victim Offering’ is the same as the ci hairpiece. The term ‘false lock’ is based off the term for shaved locks, and refers to the practice of shaving the hair of slaves or criminals and weaving it into a toupee. Minister Zheng must have understood that the Three Pheasant Robes are coupled with the tiara, the Yellow Mulberry and the Plain White robes are coupled with the wig, and the Bordered Robe is coupled with the hairpiece. The King has three sacrificial robes, all of of which coupled with the flat-topped crown, therefore, for the Queen’s three sacrificial robes, they must all be paired with the the tiara. When the ‘Nuptial’ section mentions ‘the bride in her hairpiece and black robe,’ the black robe is the Bordered Robe, and it is coupled to the hairpiece. Thus, the typical headdress for the Bordered Robe must be the hairpiece. There is also the wig, which is understood to be the headdress for the Yellow Mulberry and Plain White robes. The hairpiece is stated to be ‘worn when attending upon the King’, while previous annotations state the Plain White robe is worn ‘when greeting the King with full dignities’, which would mean that the Plain White robe coupled to the hairpiece is used to greet the King with full dignities. Here, it is stated that the hairpiece is used to attend upon the King, therefore, there must be two contexts for attending upon the King: the first, greeting the King with full honors while holding court, using the same regalia used for greeting guests, which is the wig and the Plain White robe; the second, the hairpiece and the Bordered Robe. The hairpiece and the Bordered Robe is used to receive the King in the Queen’s personal apartments. ‘When the Queen is in private, she but fastens her hair with streamers and a hairstick.’ According to the ‘Capping Rites for Common Officers’, a streamer is six chi long and used to wrap the hair. The hairstick is used to secure the hair. To fasten means to both tie the start of the hair and secure the ends. Being in private means the Queen is not alongside the King, and is by herself in her own apartments. The poem ‘Ji Ming’ from the Classic of Poetry states, The east is bright; the court is crowded’. The Mao Commentary contains the annotation ‘the east is bright means that the Lady has arrived in the King’s court wearing streamers and a hairstick.’ Yet the wives of the great barons dress the same as the Queen in their own fiefs, and as for attending court wearing a streamer and hairstick, these annotations state that the tiara, wig, and hairpiece are worn to attend sacrifices or greet guests, clearly indicating that the hairpiece is not used in private, so naturally, the hair is arranged with a streamer and hairstick. However, when the Mao Commentary states that the Lady attended court wearing a streamer and hairstick, it is because Mao Ting himself had witnessed it, and not derived from Minister Zheng’s analysis. If so, those who do not follow Zheng’s analysis might take Mao’s interpretation, as there are no texts that state a streamer and hairstick is worn in private. In actuality, the headdress for paying court to the King is the wig. Citing the Classic of Poetry’s ‘engraved and chiselled are the ornaments’, ‘zhui’ means ‘to carve’. The line ‘the Queen’s crosspins and hairsticks are all made of jade’ can be supported with the statement in the section of the Master Haberdasher that the King’s hairsticks are made of jade, and thus it is known that the King and the Queen both use jade for their ornaments. The section of the Master Haberdasher states that ‘the dukes use earstoppers of jade’, and the Classic of Poetry’s ‘there are her ear-plugs of jade’, refers to wives of the great barons, proving both the lords and their ladies use jade earstoppers, and so their crosspins and hairsticks should also be of jade. The wives of the Three Excellencies and the Three Noble Ladies also dress in Pheasant Robes, so it is clear that their crosspins and hairsticks are also constructed from jade, while the Nine Companions use ivory. The line ‘Only sacrificial regalia includes crosspins’, those who know the context, seeing that the Queen is listed separately from the Nine Companions and those ranked below them, understand that there is a difference between the attire of the Queen and the attires of the lower ranked ladies, and therefore, the crosspins are only worn alongside the Pheasant Robes, and ceremonial attire descending from the Yellow Mulberry robe do not include crosspins. Again referencing Zang Aibo’s speech from the second year of Duke Huan, ‘His ceremonial robe, crown, kneecovers, and sceptre; his girdle, kilt, buskins, and shoes; his crown’s crosspins, ear tassels, fastening strings, and crown coverings’ all refer to a man’s mianfu sacrificial regalia, and thus proves that a woman’s crosspins are only worn alongside the Three Pheasant Robes. This is the reason Minister Zheng asserts that only sacrificial regalia includes crosspins. Yet while the Yellow Mulberry and lesser ranked robes do not include crosspins, their regalia should still include ear tassels from which to hang earstoppers. Because the poem ‘Zhu’ from the Classic of Poetry includes the lines ‘The strings of his ear-stoppers were of white silk’, ‘of green silk’, and ‘of yellow silk’, referring to the tassels that subordinate officers use to suspend their earstoppers, it is known that women of lower rank also have tassels from which to suspend earstoppers. ‘They hang to the two sides of the tiara above the ears, and below each of them jade plugs dangle from ear tassels.’ The Spring and Autumn Chronicle groups ‘crosspins, ear tassels, fastening strings, and crown coverings’ together, with the ear tassels immediately following the crosspins, clearly stating that the ear tassels were created for use with the crosspins. Since the hairstick is worn horizontally, the crosspins must be worn slanting down. If so, the “heng” crosspins, which pronounced the same as the word for “horizontal”, and the reason they slant downwards but are still regarded as horizontal is because while the hairsticks are described as horizontal for penetrating horizontally through the bun, the crosspins are at the sides above the ears, so regarding the human body as vertical, they form a horizontal line. From these crosspins are suspended two earstoppers on tassels. Analyzing the ‘Odes of Yong’ portion of the Classic of Poetry, the annotations state: ‘“Pi from the first line refers to something rich or splendid. “Zhen” from the third line refers to glossy black hair. “Like clouds” refers to hair being long and beautiful. “Descending” means descending to use. “False locks” refers to a hairpiece.’ This passage is used as reference to prove that the Pheasant Robe includes crosspins, and thus Minister Zheng adds that the poem ‘refers to these ornaments’. The color of the tassels vary with the type of gem used for the earstopper. Ladies who are qualified to wear the Pheasant Robes have tassels of five colors and earstoppers of jade; those qualified for the Yellow Mulberry robe and those of lesser rank use tassels of only three colors and earstoppers of stone. Those who know the context will refer to the ‘the strings of his ear-stoppers were of white silk’ from ‘Zhu’. Minister Zheng writes in his annotations: ‘This poem describes someone following a gentleman out into the entranceway, and there, the gentleman offers him a salute. As the narrator regards the gentleman, he notices that his earstoppers have strings of white silk, referring to the strings from which his earstoppers hang down, cloth ear tassels which are woven from thread of five colors for rulers, but only three colors for subordinate officers. Strings of white describe the color first noticed by the speaker.’ The next line is ‘And there were appended to them beautiful Hua-stones.’ The annotation states that hua-stones are ‘a sort of precious stone.’ The next stanzas include ‘green silk’ and ‘yellow silk’, encompassing the three colors of thread used by subordinate officers, and therefore, the annotations explain that rulers use five colors of threads. The Classic of Poetry also includes ‘ear-plugs of jade’, which proves that a ruler’s wife uses earstoppers of jade, so a subordinate officer’s wife would be the same as her husband in using earstoppers of opaque gems. The Mao Commentary defines “white” to refer to ivory earstoppers. The reason Minister Zheng does not agree with this assessment is because, if the earstoppers themselves were of ivory, why mention the opaque gems? As a result, Minister Zheng interprets the colors to refer to the tassels of the earstoppers. ‘Ji, or Hairstick: used to curl up the hair.’ The ‘Brief Record of Funeral Robes’ in Minister Zheng’s annotations for the Book of Rites also state that ‘the hairstick and the belt must remain as they were first curled or fastened.’ ‘Outer and Inner Titled Women dressed in the Yellow Mulberry and Plain White robes wear wigs, while those dressed in the black Bordered Robe wear hairpieces.’ Those who know the context will refer to the the ‘Nuptial’ section mentioning ‘the bride in her hairpiece and black robe’, and understand that the black robe is the Bordered Robe. Since the groom, a common officer, wears a nobleman’s square-topped cap to greet her, in an exception from clothing restrictions, the common officer’s bride, similarly elevated, should wear the Bordered Robe and decorate her hair with the hairpiece. Since the Bordered Robe is coupled with the hairpiece, and the Three Pheasant Robes are coupled with the tiara, thus it stands to reason that the Yellow Mulberry and the Plain White robes are coupled with the wig. ‘When the Outer and Inner Titled women are not assisting the Queen in rituals of sacrifices or greeting guests, their regalia goes down a rank back in their own homes.’ Those who know the context understand that the wives of great officers wear the Plain White robes with the wig and the wives of common officers wear the Bordered Robe with the hairpiece when in company of the Queen. ‘Rites of the Secondary Pen Victim Offering’ and ‘Rites of of the Single Victim Food Offering’ detail the rites of sacrifice in ancestral temples for great and common officers and their wives’ participation. ‘Rites of of the Single Victim Food Offering’ states ‘‘The wife of the Master of Ceremonies, with her hair wrapped in streamers, and wearing dark Everyday Robes’ and ‘Rites of the Secondary Pen Victim Offering’ states ‘Then the wife of the host builds up her hair with false locks. She wears the Bordered Robe with wide flowing sleeves.’ As the wife of the great officer’s wide flowing sleeves were worthy of notice, and she does not wear the wig, it is apparent that her ceremonial attire is of a lower rank in her own home. Again with ‘Rites of the Secondary Pen Victim Offering’ as evidence, ‘the wide flowing sleeves are the sleeves of the Bordered Robe’.’ This is the explanation Minister Zheng gives for ‘Rites of the Secondary Pen Victim Offering’, that the host’s wife’s wide flowing sleeves come from widening the sleeves of the Bordered Robe. The previous text only states that the host’s wife wears garments with wide flowing sleeves, with the explanation of widening the sleeves of the Bordered Robe differing from the original text. Yet when the wife of common officers wear the Everyday Robes and the Bordered Robe for participating in sacrifices and marrying, they do not widen the sleeves. Here, the wife of the great officer widens the sleeve of her Everyday Robes to form the sleeves of the Bordered Robe. As the wives of great officers and common officers both wear Everyday Robes, and the sleeves of the Everyday Robes are not mentioned as wide or flowing, widened sleeves must belong on the Bordered Robe. ‘The wives of the great barons dress in the same clothes as the queen in their own fiefs.’ The wives of the various ministers assist the Queen and the Great Ladies in offering sacrifices, while the Great Ladies themselves do not assist the Queen. Therefore, in their own fiefs, they use the same regalia as the Queen. As to how similar, the wife of the great dukes qualify for the Great Pheasant robe down to the Bordered Robe. The Great Pheasant robe is used for paying reverence to the ancestral temple alongside the ruler, the Lesser Pheasant robe is used in sacrifices to the various gods of nature, the Courtyard Pheasant robe is used in sacrifices to all the lesser gods, the Yellow Mulberry robe is used for the Silkworm Ceremony, the Plain White Robe is used for greeting guests and paying court to the ruler, the Bordered Robe is used for greeting the ruler. The wives of the marquesses and counts qualify for the Lesser Pheasant and all robes lower in rank. The Lesser Pheasant is used to accompany the ruler to sacrifices to the ancestral temple and the various gods of nature, with the Courtyard Pheasant and all the other robes used for the same purposes as those of a Duchess. The wives of the viscounts and barons qualify for the Courtyard Pheasant and all robes lower in rank. The Courtyard Pheasant is used to accompany the ruler to sacrifices to the ancestral temple, the various gods of nature, and all the lesser gods, with the Yellow Mulberry and the other robes used for the same purpose as those of a Marchioness or Countess, as well as streamers and hairsticks coupled with the Everyday Robe for private use. The wives of the descendants of the kings of the previous dynasties and the Duchess of Lu are allowed the regalia of the great dukes. Thus the ‘Places in the Hall of Distinction’ section of the Book of Rites states: ‘In the last month of summer, the sixth month, they used the ceremonies of the great sacrifice in sacrificing to the Duke of Zhou in the great ancestral temple…[the ruler’s] wife, in her tiara and Great Pheasant robe…’”

The Three Pheasant Robes from Illustrated Three Rituals

In summary, a Muzhui is a sort cap from the Xia dynasty, similar to the Zhangfu of the Shang Dynasty and the Weimo of the Zhou Dynasty. Therefore, the Zhuishi or Chief Jeweller is the officer that oversees the royal headdresses. The Queen’s six types of headdresses include the tiara, wig, hairpiece, cap, cross-pins, and hairsticks. A “zhui” is a form of cap and crosspins are hairpins that hold the cap in place. The tiara is a headdress that covers the head, which scholars of the Han Dynasty believe to the prototype the buyao, but Tang Dynasty scholars doubt this theory and clarify that the “six jewels” of the Classic of Poetry refer to a tiara being worn alongside hairsticks, with six decorations, but the decorations themselves were never defined. A wig is used to coif the hair, and scholars of the Han Dynasty believe it to be the prototype of the false coiffure, a very popular form of wig, but the Tang Dynasty scholars also doubt this interpretation. A wig is a ceremonial decoration used in conjunction with the Yellow Mulberry robe for Silkworm ceremonies, as well as alongside the the Plain White robe to greet guests or pay court to the King. A hairpiece is another form of wig, the ancient version of hair extensions, called “false locks” during the Han Dynasty. It is woven from real human hair and used to accompany the Bordered Robe when greeting the king as his spouse. The hairpiece and the black Bordered Robe are also the wedding outfit for low level officers and commoners, with the Bordered Robe being referred to by color in the context of a wedding. When the Queen is by herself in her private apartments, she only uses a strip of cloth called a “streamer” to wrap up her hair and pin it with a hairstick. She also wears a modified Bordered Robe called the Everyday Robes. The zhui cap is paired with the crosspins. The Queeen’s crosspins are made of jade and come in a pair of left and right, with one worn on each side of the tiara, slanted with their heads coming just above the ears. A pair of earstoppers dangle from tassels attached to the head of the crosspin. Only sacrificial regalia includes crosspins, and Tang Dynasty scholars point out that sacrificial regalia is the Pheasant Robe. The Yellow Mulberry and other ceremonial robes do not include crosspins, but still have dangling earstoppers. Both crosspins slant down while the hairstick is pinned horizontally through the hair. The lines ‘How rich and splendid is her pheasant-figured robe! Her black hair in masses like clouds, no false locks does she descend to. There are her ear-plugs of jade…’ from the Classic of Poetry describes the crosspins. A hairstick is used to curl up and arrange the hair, and there are special requirements for the hairsticks used in funerals. The wives of the various ministers use ceremonial outfits of lesser rank in their own home than around the queen, but the wives of the feudal lords use similar regalia as the queen, only with different types of Pheasant Robe. From the pre-Qin rites, as well as the way that Han Dynasty and Tang Dynasty scholars have interpreted them, the buyao is a vertical ornament that also covers the head. It is a radically different concept than the crosspin, which dangles beads from its end.

Yet after the Zhou Dynasty, there truly existed a form of a single-pronged, needlelike hair ornament with beads hanging from the end. As to what it looks like, and what it is, one must understand a certain ornament that was promoted alongside the buyao: zan-er (簪珥), the ear-bead.

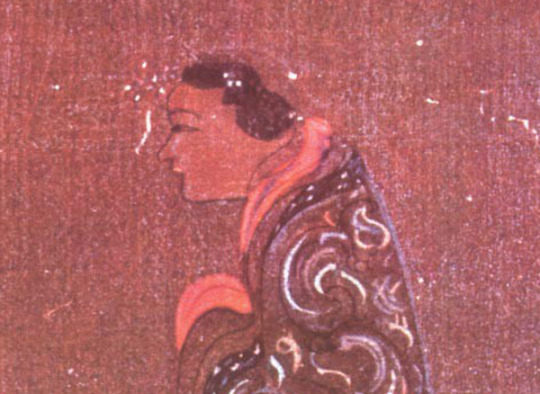

Funeral banner of Lady Dai depicting Xin Zhui wearing a hair ornament with strings of white beads

Pre-Qin Dynasty documents that mention zan-er are the ‘King Mu of Zhou’ section of the Liezi: “the King proceeded to fill [the palace] with maidens, selected from Zheng and Wei, of the most exquisite and delicate beauty. They were anointed with fragrant perfumes, adorned with moth-eyebrows, provided with jewelled hairpins and ear beads, and arrayed in the finest silks, with costly satin trains. Their faces were powdered, and their eyebrows pencilled, their girdles were studded with precious stones. All manner of sweet-scented plants filled the palace with their odours, and ravishing music of the olden time was played to the honoured guest. Every month he was presented with fresh and costly raiment; every morning he had set before him some new and delicious food.”And the ‘Economic Policies Part I” section of Guanzi: “raising items like hairpins and ear-beads to the price of thousands of taels of gold, while they are made of jade and gems, shall acquire the homage of the land of Kunlun, eight thousand miles away. If there is no one to regulate the prices of these precious commodities, nor anyone to forge economic ties between lands, so that distantly space areas cannot benefit from each other, then none of the surrounding barbarian nations will do you homage.” Liezi refers to the lavish treatment King Mu gave to an enlightened man, with one of the ornaments adorning the palace beauties being “zan-er”. Guanzi has Guan Zhong giving Duke Huan of Qi an economics lesson, with zan-er being listed as a precious item.

Later, in the waning years of the Warring States period, Li Si of Qin submitted a petition In Advice Against the Driving Away of Guest Immigrants, mentioning: “If all the decorations of the palace, the items of entertainment, and the items that please Your Majesty’s eyes and ears must be produced in Qin, then hairpins topped with the pearls of the land of Wan, ear decorations created from the unrounded studs of the land of Fu, fine silk clothing from the land of Dong-e, and brocaded decorations would not be offered before Your Majesty. Nor might the sultry girls of Zhao stand at Your Majesty’s side.” Li Si offers a powerful pro-immigration argument by comparing the imported enjoyments of Qin Shihuang to the immigrant scholars who have come to Qin. At the same time, the “Outer Collection of Sayings” section of Han Fei’s Hanfeizi mentions “Lord Jingguo presenting ten ear-beads”, an allusion to Tian Ying, the Lord Jingguo. The Strategies of the Warring States is much more detailed: “The King of Qi’s Queen died. There were seven beautiful young women, all of whom had access to him. The Duke of Xue wished to know which of them the King wished to appoint. So he presented seven ear ornaments, one of which was particularly beautiful. On the morrow, he looked where the beautiful ear ornament was. He urged the King to appoint her as his Queen.” The son of King Wei of Qi, Tian Ying, was the feudal lord of Xue. After the Queen died, he gave his father either ten or seven “ear ornaments”, or “er”. One of them was fancier than the others, and the next day, he observed the various consorts and judged who among them was most favored and should be made queen based on who had the best “ear ornament.” From these descriptions, both hairpins and ear ornaments are precious items, and “zan-er” is an ornament of noble women. Removing the zan-er, like removing the hat and shoes, is an act of penance. In Records of the Grand Historian, the Western Han historian Sima Qian records that when Emperor Wu of Han accused Lady Gouyi of crimes and ordered her executed, “the lady removed her zan-er and prostrated herself.” Liu Xiang’s Biographies of Exemplary Women records that King Xuan of Zhou was once so enamoured with the beauty of his new bride that he thought of nothing but staying at her side, ignoring matters of state in the meantime. His wife was a wise woman, who took upon herself the responsibility to advise the King, albeit with an unorthodox method. “The queen removed her zan-er and locked herself away in the slave quarters as a criminal awaiting punishment. She sent her governess to deliver a message to the King saying, ‘Your concubine is worthless. Your concubine’s lust is apparent, in that she has seduced the King to discard the proper rituals and abstain from governance, and has transformed the King into a man who abandons virtue for pleasures of the flesh.’” The Later Han historian Xun Yue’s the Earlier Chronicles of Han records in the Chronicles of Emperor Xiaowu that when Princess Royale Guantao’s affair with Dong Yan was discovered, “the Princes removed her zan-er, and, barefoot, prostrated herself and apologized for her crimes.” The records show that as early as the Qin Dynasty and the Han Dynasty, zan-er had become a common ornament among high ranking ladies, as well as a symbol of their status. To wear the ornament was to show that one was among the highest nobility, to remove it an act of humble penance.

What sort of ornament was this zan-er? The “zan” part is easy to explain. It is the long, needle-like, single-pronged hairpin traditionally used by Chinese women. The “er” part is more complicated. First it must be made clear that during the Qin and Han dynasties, “er” could refer to any decorations that stuck out to the side of an item like ears. For example, the “Astronomy” chapter of Huainanzi uses “er” to describe the silkworm’s production of silk. Master Lu’s Commentary of Spring and Autumn uses “er” to refer to a meteorological phenomenon. The Songs of Chu use “er” to mean the handle of a sword. Yet in all the texts, when “er” is used as an item of jewelry, it is almost always coupled with the “zan”. The “Definitions” section of Li Si’s Cang-E Chapter describes “er” as “beads on the ear; beads hanging from ear ornaments are called ‘er’”. The Shuowen Jiezi dictionary compiled by Xu Shen in the time of Emperor He of Han defines “er” as “ear-stoppers; grouped with the jade particle, pronounced like the word for ‘ear’.” It further defines ear-stoppers as “Using jade to plug the ears; grouped with the jade particle, pronounced like the word for ‘truth.’ The Classic of Poetry mentions ‘there are her ear-plugs of jade.’” The Shiming defines earstoppers as “barriers; worn by the ears to caution people against listening without thinking, so that they might exercise discretion with what they hear. They might also be called ear-plugs, which mean that they can be plugged into the ears, so that they might shut out noise. That is why there is a saying that ‘lest you be blind and deaf, be not a father nor mother in law.’” These definitions, combined with the fact that “er” is written with the word for “jade” next to the word for “ear”, can cause a reader to conclude that an “er” is in fact an earring. Not only do modern people hold this misconception, but so did the ancients after the Song Dynasty. For example, the Broad Rimes compiled by Chen Pengnian in the era of Emperor Zhenzong of Song, defines “er” as “ear ornaments.” It seems then that zan-er are two different ornaments: a hairpin and a pair of earrings. Ancient China did have earrings, the earliest type appearing during the Xia and Shang Dynasties. They were called “jue”, written as two words for “jade” placed next to each other. Like its shape, the “jue” earrings were two jade disks with a round hole in the middle and a long, narrow gap at the side. It could be worn by slipping the earlobe in the gap, or running the earlobe through with a length of rope, on which could also be threaded the earring. After the Zhou Dynasty, it became obsolete and survived as the singular “jue” ornament worn at the waist. Then, during the Later Han Dynasty, a new ear ornament, the moon-bright pearls, spread into China alongside Buddhism. These pearls had a pinched, drum-like profile, and two flat, round ends, appearing to be a bright moon. They were not so easy to wear as modern earrings, requiring the wearer to first make a hole on the ear and start with a small ornament, and then gradually increase the size until the piercing becomes large enough to admit the moon-bright pearls. At the same time, because of the weight of the ornaments, the earlobes lengthen and droop, which is the true cause of Buddha’s big ears. Several Han Dynasty terracotta tomb figurines depict women with ear piercings, reflecting the popularity of ear ornaments.

Shang and Zhou Dynasty jade jue

Han Dynasty moon-bright pearls

Early Tang Dynasty mural of Bodhisattva with ear ornaments

However, the greatest obstacle to this interpretation is that the Shiming defines moon-bright pearls as: “beads that require piercing the ears are called studs; this custom was originally found among barbarian tries. The barbarian women are lascivious and flighty, so they use these clinking ear ornaments to restrain their movements. In the modern day, Chinese people have started imitating them.” Since piercing the ears is a barbarian custom, it would not have been admitted into formal rituals, or become part of ceremonial clothing to be worn by the people of the Zhou Dynasty. Thus, the “zan-er” that appears as a part of the Imperial regalia of the Later Han must be some other form of ornament. Returning to “ear-plugs” a commentary by Wang Fuzhi of the Qing Dynasty on the Classic of Poetry states: “ear-plugs, or studs, are decorations on the Imperial crown.” Ear-plugs have been a decoration on the crowns of several generations of emperors. Ancient caps and crowns required a hairpin to pin it to a man’s hairbun, and on either side of the hairpin for the mianfu crown, one jade ball would be suspended from either side, left and right, and allowed to hang down next to the ears. These are the “ear-plugs”, which remind the emperor to listen to good advice and dismiss idle chit-chat.

Mian crown with earplugs

From the information above, we can conclude that a zan-er is a female version of the earplug. Like the male version, it consists of beads hanging down from the ends of hairpins. The beads reach to the sides of the ears, and thus would be written with a character composed of “jade” and “ear”. The Later Book of Han actually clearly records the zan-er as a single ornament. The Empress’ zan-er requirements were: “Zan-er. Er–dangling drum-shape ear beads. The zan, or hairstick, has a body constructed of turtle shell, one chi in length. It ends are covered in flower disks, which is decorated with the pattern of a phoenix bird with feathers of jadeite. Underneath there are white beads from which hang golden nie ornaments. The hairstick is worn horizontal, from left to right, and used to secure the hair band. The zan-er all share the same design, but the body differs depending on rank of the wearer.” The zan-er is a hairpin which has drum-shaped beads hanging down toward the sides of the ears. Its body is made of turtle shell and very long, while both its ends sport flower disks or huasheng, a sort of circular plate-shaped ornament decorated with flower designs. The ceremonial regalia zan-er has flower disks decorated with a phoenix pattern, with jadeite arranged into feathers, and underneath are white beads and golden “nie”. “Nie,” usually meaning “tweezers”, in this context, is used to refer to small, thin ornaments that hang down. Therefore, golden nie are strings of small golden ornaments. Every zan-er has two identical heads, and is arranged horizontally in the coiffure to secure the headband. All the noblewomen who qualify have the same design of zan-er, but the body of the ornament differs according to rank.

In summary, Zan-er before the Tang Dynasty refers to the modern day dangling bead buyao!

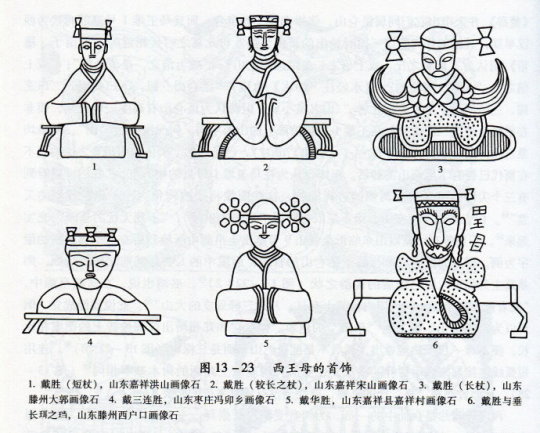

Han Dynasty depictions of the goddess Queen Mother of the West wearing double-headed flower disks

Reconstruction of woman wearing ornament with drum-shaped beads

As to why zan-er and buyao would be confused for each other, I have not yet done enough research to find the answer. I only know that late into the Tang period, as recorded in the Song Dynasty author Wang Dang’s Tang Dynasty Prose, “In the Changqing era, the jewelry of the women of the Capital included gold, jasper, pearls, and jadeite; hairsticks, combs, and buyao, not one of which was not exceedingly beautiful, and they were called the ‘hundred unknowns.’ Women shaved away their brows and drew three or four horizontal purple lines beneath their eyes, a look called the “bloody makeup”. During the late dynasty, buyao had become very widespread, and was listed along with hairsticks and combs as commonly seen ornaments. Based on excavated artifacts, this was the dangling pearl variety of buyao. By that time, the definition of buyao had already changed. By the time of the Song Dynasty, according to Miscellaneous Facts Among the Orchids (lost, selections cited in the Yuan Dynasty short story collection Records of Sakra’s Divine Library), “Everyone believes buyao is used by women to hold up their hair. That is incorrect. It is built by twisting silver wires into the shape of flowering branches, then pinned behind the hair so it might sway with every step, increasing a woman’s sensual allure. That is why it is called the buyao, the step-swayer”. At this point, the populace no longer recognised the branching buyao, and instead only know about buyao with strings of beads. My own hypothesis is that with the advent of Buddishm and flower crowns that sought to emulate the decorations of Bodhisattva iconography, the Han Dynasty zan-er began to lose its appeal, and evolved into the crown wings that can be seen in modern phoenix crowns. When the dangling pearl buyao came back into vogue, everyone had already forgotten the previous name, remembering only the buyao.

Tang Dynasty stone line engraving from Tomb of Princess Yongtai, depicting woman wearing ornament with dangling beads

Court Ladies Wearing Flowered Headdresses attributed to Zhou Fang

During the Northern and Southern Dynasties, there was yet another type of hair ornament called the chai-nie, the tweezer clips. Chai are double-pronged hairpins akin to the modern day hairclip. Nie has already been defined above. In the context of jewelry, it refers to small, lightweight dangling decorations. Chai-nie were also common ornaments during this time, as can be seen from Biography of Empress Wang Wen-an from the Book of Southern Qi: “The Crown Prince issued new and luxurious clothes and jewels for all his palace women, yet the Queen’s bed canopy and the items in her room were the same as old, and she only had ten or so chai-nie.”

This type of ornament also remained in use into the modern era, only it is referred to with the blanket term buyao. The modern day buyao includes both single and double prong variants.

Late Tang Dynasty “buyao” double-prong hairpin

In conclusion, for all the people out there studying hanfu and ancient texts, please be mindful: Before the Tang Dynasty, when texts refer to buyao, they are referring to a vertical ornament with a base at the bottom and spreading branches on top. Zan-er refer to horizontal, single ended or double ended, single-prong ornament with trailing beads at the end. Chai-nie refers to a double-pronged ornament trailing beads at the end. As for clothing in the modern era, the time is so removed from the Tang Dynasty that it makes no difference whether an ornament is buyao or zan-er.

521 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Facial makeup was an elaborate process for Tang Dynasty women. It began with a foundation of face powder, followed by rouge and a dusting of light yellow powder. Bluish black eyebrows were then painstakingly painted in, lipstick applied, and dimples either added or accentuated. Last was an ornamental design either pasted or painted on the forehead.

Although facial makeup had not been invented in the Tang Dynasty, it advanced during this progressive era.

Eyebrows have always taken precedence within Chinese facial aesthetics, each style with its own name. Tang Dynasty eyebrows painted in bluish black were called daimei, long, fine eyebrows were emei, and guangmei eyebrows were short and thick. Eyebrow modes seen in the imperial palace included the yuanyang, xiaoshan, sanfeng, chuizhu, yueleng, fenshao, hanyan, fuyun, daoyun, and wuyue. Popular folk eyebrow styles included the liuye, queyue, kuo and bazi.

The ornamental designs Tang beauties pasted on their foreheads were often of bird feathers or black paper, and possibly of shell, goldleaf, fishbone or mica. Or they would simply paint on a motif.

The scope for innovation in these fashionable make up trends had been exhausted by the late Tang Dynasty, when women stopped using face powder and colored their lips black, in the “Sad” or “Tear” gothic mode that gave a more dramatic emphasis to feminine beauty.

225 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Video and Gifs: 100 Years of Beauty in 1 Minute: China

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Traditional Chinese hanfu and makeup of Tang dynasty by 杭州纳兰

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Trying to do the 1940s clothing…… I am really bad at drawing hairstyles lol. I still feel that Chunyan should have short hair at that time instead of the original one. (´・Д・)」

Tbh, cheongsam had its best styles from the late 20s to the 40s. Since it was a fashion that kept following and absorbing the ideas of western fashion, it started to exaggerate the curves of female figure in the 50s which is honestly too much.

192 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ねーねとにーに

Pixiv ID: 30914298

Member: 2950176 - ナイトメリー

※Posted with the artist’s permission

~Please ask the artist first if you want to repost the artist’s art~

78 notes

·

View notes