Text

Moby Dick

There is a witchery in the sea, its songs and stories, and in the mere sight of a ship, and the sailor's dress, especially to a young mind, which has done more to man navies, and fill merchantmen, than all the press gangs of Europe.

Richard Henry Dana Jr., Two Years before the Mast, 1840

0 notes

Text

Economic Statecraft

Man cannot discover new oceans unless he has the courage to lose sight of the shore.

André Gide, 1947

Between the postcolonial Tonnage Act, lighthouse proliferation, the Erie Canal’s inauguration, mail subsidies, the Panama Canal moonshot and the Great Depression’s ex post legislation statecraft has perennially been a prime mover. These vignettes essentially belie free market purists whose reductive views do not align with history. At critical moments across America’s storied past has industrial policy purveyed the seedbed for economic development. Of course the magic of free enterprise creates wealth in the spirit of Adam Smith’s invisible hand but government perpetually remains a handmaiden to it bereft of which nothing would take root in barren soil. A myopic exegesis conflates effect with cause. Such a ‘chicken before the egg’ fallacy remains blinkered to how the apposite conditions must exist as a precursor to the works of laissez-faire capitalism. Ergo there is a special place for government when a country finds itself in the midst of industrializing. Rather than anathema to growth this intervention begets a matrix wherein firms are vested with the latitude to innovate whilst immune to liabilities hence their carte blanche enables them to gestate. Or if not for the right infrastructure these same outfits would be deprived of markets particularly where it relates to their supply chains.

During the nascent years of the Republic in the wake of the Revolutionary War economic nationalism bore the imprimatur of Alexander Hamilton whose advocacy captured a vast audience. With the inordinate clout of British imperialism still looming large over America it behooved President George Washington to channel this doctrine in his government so London’s predations could be checked. It followed that the Tonnage Act of 1789 imposed onerous levies on foreign ships not only as a method to generate revenue but equally to hem in infant industries against the maritime monopoly of Britain. Import-competing shipbuilders could finally carve out a space for themselves where they were once unable. Henceforth America would not be beholden to its counterparts for the carriage of its wares and fare nor would it be idle in the defence of its proper interests overseas. By discriminating against competitors domestic industries catapulted the country into the pantheon of a seaborne power. By stimulating demand for American-made ships producers reaped a windfall of capital whereby they could plough it into their expansion. By running afoul of free trade orthodoxy foreign industries no longer prostrated shipbuilding at home. The Tonnage Act made America a great power to be reckoned with.

Whilst sharing the same vintage as this legislation the federalization of maritime infrastructure also came to substitute for the piecemeal efforts led by states in governing lighthouses. Where trade routes might have once been neglected these upright sentinels lighting the path for ships began to take precedence. Since private investment did not square with the reality of such a public good insofar as the free-rider dilemma disincentivized individuals from contributing to its provision this beckoned government to intercede. Thereafter lighthouses became the ward of the federal treasury. Rather than fall into disuse the proper funds saw to the upkeep of this infrastructure. Lighthouses were unambiguously the sine quo non to the safe passage of ships and this industrial policy made sure that underinvestment no longer beleaguered their operation. Through the mitigation of maritime hazards government attended to the constellation of interests between shipwrights and mariners who could now be assuaged of their anxiety about voyages at sea. Were it not for the Lighthouse Act these same trips would be fraught with the perils of having vessels run aground or worse. Insurers thus breathed a sigh of relief. Although perhaps a roundabout way this investment certainly gave patronage to the maritime industry.

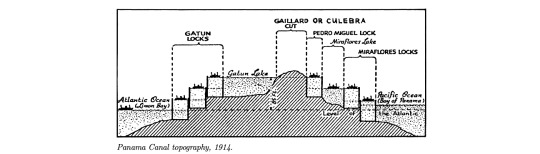

In the same vein as infrastructure the heavy-handed industrial policies giving vent to the Erie and Panama Canals were equally landmarks in America’s development. By cleaving a path through the wilds of the Adirondack region for a gateway to the Atlantic or parting the Isthmus of Panama in two it followed that dividends were had by all. America’s breadbasket in the interior would unite with the cosmopolitan metropolis of New York and the quasi-teleportation portal in the South abridged the journey of commerce between the Western and Eastern seaboards. These corollaries to industrial policy birthed westward expansion in keeping with the providence of Manifest Destiny before the ubiquity of railroads. Both of these monuments to government dirigisme truncated time and transportation costs such that these shortcuts enhanced the competitiveness of America’s exports and imports. Where in a bygone time the prohibitive sum of outlays deterred industrialization now the economic calculus indelibly changed. What these monolithic pieces of infrastructure wrought then was a reconfiguration of trade from a dribble to a torrent of volume. Quite precipitously were capitalism’s animal spirits awakened once nature had been conquered between the Hudson River and Lake Erie or via Panama’s thoroughfare.

The last method by which America trafficked in industrial policy for the maritime sector since jettisoning the British yoke of imperialism entailed both mail and direct subsidies. The former in the guise of the 1845 and 1847 Acts of Congress underwrote packet ships and steamships alike as a stimulus to harness the winds of commerce. By subsidizing mail service Washington feathered an impetus to businesses so they may bootstrap their own growth. A steady stream of revenue promised these firms a lifeline to weather the vagaries of markets with a long term outlook to plough capital into further expansion whether it be in the size of fleets or in the number of trade routes. Upon lowering risk it made private investment more attractive. In turn a stronger Merchant Marine would be a counterpoise to the British Empire that long claimed dominion over the seas. As for direct subsidies like the 1916 Shipping Act or the 1936 Merchant Marine Act they centralized authority between the Shipping Board and the Maritime Commission respectively in order to spur the drumbeat of industry. America’s supply chains diversified in earnest under their purview with the buildup of inventory in ships. Rather than being some derivative footnote all the aforementioned industrial policies nurtured America until it bestrode the world like a giant.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Modernizing America's Fleet

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

William Butler Yeats, The Second Coming, 1919

Although President Woodrow Wilson was partial to isolationism his dovish predilection could not be reconciled with WWI which contravened all etiquette pertaining to freedom of the seas. German U-boats prowling the North Atlantic ran roughshod over ethics governing the longstanding neutrality of merchant shipping in an escalation of submarine warfare. With material losses mounting akin to a game of cat and mouse across unfriendly waters an existential threat emerged against Allied powers. Europe’s fratricide of the Great War made obsolete the traditions of yore where belligerence was once reserved for combatants alone away from civilians. With America’s ships imperilled the federal government took it upon itself to create the world’s largest fleet by 1922 (Roland 2007). Six years out from the Act’s inception the gross tonnage of vessels soared by 117 percent in a renaissance at sea for the fledgling economy. How the heyday of shipbuilding came to be was through the Act’s Shipping Board which fostered the industry’s growth in a centralized manner. No longer would the Merchant Marine languish as statesmen recognized it to be part and parcel of America’s well-being with the floodgates of federal funding now open. A building boom was afoot.

The primary mandate of this legislation was the construction of ships courtesy of a $3.3b fiscal infusion after a suite of rounds in financing (Bess and Martin 1981). Provisions of this crash program enshrined the high watermark of building three thousand new vessels in short order for the purpose of seagoing commerce in what became America’s boldest industrial policy hitherto (Lawrence 1973). Government would claim ownership over half of America’s fleet and later sought to offload it onto the private sector at competitive prices following WWI’s armistice. What this industrial policy did was reverse the torpor afflicting native shipbuilders when Europe commandeered its own vessels for war whereby a void was created for indigenous production. As the spectre of hostilities expropriated foreign vessels and German submarines further exacerbated the shortage the Act remedied the quagmire in which America found itself. Shipyards changed into factories of the sea in shoring up the Merchant Marine upon the influx of new capital. Necessity was the mother of invention and the quantitative surge borne from war quickly replenished the stock of vessels in the country’s fleet. Mobilization and modernization were thus functions of this industrial policy as mass production saw America take to the seas with gusto.

With the statecraft of the Shipping Act of 1916 engendering a certain level of economic autarky the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 further consolidated this reality. Also referred to by its nom de guerre of the ‘Jones Act’ this legislation departed from the ancien régime of giving liberties to foreign ships by making trade between American ports the sole preserve of domestic shipowners. This species of protectionism vouchsafed a captive market to American mariners and shipbuilders as a way to militate against the gales of international competition. So influential was this reform that well-nigh half of all American commerce sailed aboard domestic ships in 1920 versus the meagre 10 percent in 1900 (Smith 2004). Under the auspices of the Jones Act did the maritime sector industrialize in earnest. Although the industrial policy’s detractors are correct that non-contiguous regions like Alaska or Guam ponied up higher outlays for goods the positive externalities were many: (1) a robust merchant marine would be a bellwether for national security; (2) the policy was a fillip to shipbuilding. These vessels could then be readily pressed into service in times of war whilst government hedged against any encroachment on the sector by outsiders. The WWI surplus of ships being plied to expand trade was thereby a boon to the economy.

Later in the interwar years the Merchant Marine Act of 1936 epitomized the Magna Carta of industrial policy in shipbuilding. Somewhat a laggard in the adoption of new technology like the substitution of diesel oil for coal the modernization of America’s fleet would be heavily subsidized by the federal government to remedy this anachronism. Up to 50 percent of construction and operating costs were underwritten by this fiscal policy in keeping parity with international market prices to incentivize domestic shipyards. Older vessels of twenty years or more however would not be grandfathered into this scheme so as to compel the retirement of vessels which approached obsolescence. Such industrial policy arrested the sector’s decline when mail contract subsidies were too impotent to be of substance. Where once the industry was in distress America’s Merchant Marine transformed into the envy of the world. Subsidies equally mitigated risk for financiers who may have otherwise looked askance at investment in the sector. As foreign shipowners boasted a competitive advantage in construction and operating costs it was therefore incumbent on President Roosevelt to preserve America’s waterborne commerce. The Merchant Marine Act of 1936 did precisely that with auspicious timing in the prelude to WWII.

A robust industry was the progeny of this industrial policy insofar as 5,592 merchant ships were manufactured between 1942 and 1945 in the fight against the Axis Powers (Harris and Kennedy 1965). Shipbuilders were already manufacturing at scale when wartime production saw an armada of Liberty, Victory, tanker and cargo ships exiting shipyards. As the world reeled from war the infrastructure had long been in place to expedite the output of vessels bound for the Atlantic and Pacific theatres. What throttled America’s Merchant Marine prior to 1936 was the nebulous nature of mail subsidies which sowed confusion in how the patronage of government backstopped the industry. The structure showed to be far too atomized for a proper audit (Hessdoerfer 1984: 23). The multitude of postal contracts distorted any stocktaking as a demerit to America’s fleet. This predicament like some sort of de facto sabotage lent credence to the government plying direct subsidies for the sake of the industry’s buildout. Such paternalism averted the brinkmanship of letting the status quo prevail lest the entire fleet be rendered obsolete all at once. America’s ships were aging too quickly. As the economy atrophied in the jaws of the Depression President Roosevelt’s policy would herald a paradigm shift in the governance of shipbuilding.

#Shipping Act of 1916#Merchant Marine Act of 1936#President Woodrow Wilson#President Franklin D. Roosevelt#Industrial Policy

0 notes

Text

The Panama Canal's Epidemiology

Cowards die many times before their deaths;

The valiant never taste of death but once.

William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, 1599

Another oversight shunned by Americans but had hampered the French was the latter’s want of disease control claiming 22,000 lives. The Canal’s predecessors seem to have stood idly by as the grim toll of pestilence decimated the ranks of workers. The ubiquity of funeral trains laden with remains ravaged by malaria and yellow fever testified to the illiteracy for epidemiology on the isthmus at the time. The arrival in 1904 of Colonel William Gorgas who helmed the Department of Sanitation would herald a paradigm shift. In a bid to end the miasma of stagnation throttling the Canal’s progress a regimen for prophylaxis displaced the unreconstructed one of therapeutics. In taking stock of this epidemic Gorgas took the offensive with his petition for countermeasures against the blight of mosquitos which bore culpability for the tyranny of death. In a knee-jerk response Chief Engineer John Wallace balked at this cri de coeur and abruptly resigned but his successor John Stevens elected instead to mobilize four thousands engineers against this vector of infirmity. Such a theory of transmission first gained prominence in 1900 when Gorgas and his peer Dr Walter Reed quarterbacked off the scientific corpus of physician Carlos Finlay who fathomed causality between mosquitos and Cuba’s mortality rate.

The capital of Havana was once a necropolis-cum-laboratory writ large for testing the pathogenesis of disease when the dated Miasma Theory had long been medical lore. This established dogma equated illness with fetid air but germ theory began to gain currency over the cognoscenti particularly after physician John Snow mapped London’s cholera outbreak in 1854 to a contaminated water pump. Neither fomites nor foul gasses from decaying matter sickened the population as it was firmly believed. By the dawn of the 20th century a consensus that looked askance at the communicability of polluted air crescendoed into Cuba’s Yellow Fever Commission which defenestrated this relic of a theory for good. Although the idea specific to mosquito-borne transmission languished in obscurity for two decades due to a lack of empirical evidence it was Gorgas and Reed who put the hypothesis under scrutiny anew. Amidst the onslaught of yellow fever besieging Havana in the wake of the Spanish-American War a public health crusade was set loose to pinpoint the cause. At Camp Lazear mosquitos revealed themselves to be the vector for the rogues’ gallery of disease running amok across the archipelago of islands. No longer captured by ignorance a new edict thus spurred proactive measures to spoil the habitat of these winged critters.

Lessons of sanitation from Cuba were exported to Panama three years later so the Canal could be salvaged after the heavy toll exacted upon the French. The intervention by Gorgas and his army of engineers would consume 35 percent of the project’s lucre in its most prolific phase which systematically fumigated buildings, scythed down tall grass and drained standing water (Rogers 2014: 156). The big dike would have come to naught were it not for such mitigation lest panic prompt workers to flee which they initially did. Fear was sown most acutely in the spring of 1905 when three-quarters of expatriates boarded steamers bound for New York (Rogers 2014). In fact Chief Engineer Wallace tendered his resignation amongst this very same cohort to escape the harrowing crisis a mere fifteen months after his appointment. Prior to Gorgas’ breakthrough this pall of phobia put the Canal at risk since the etiology of yellow fever and malaria was little understood and speculation gave rise to hysteria. The psychological trauma borne from this indiscriminate threat spared no one as labourers and administrators alike were prostrate with fear when symptoms between jaundice and hemorrhages gnawed at morale. Salvation against such defeatism came by Gorgas who won credence as the spectre of disease subsided.

By happenstance Roosevelt’s industrial policy on the Isthmus engendered nothing short of a revolution in epidemiology. Many of the remedies to ward off infection would be universally adopted much like how screen windows find themselves in homes today. After Gorgas procured $90k of these copper meshes for structures abutting the Canal this same feature saw prevalence in the abodes of South Florida until it evolved into standard practice for homebuilders (Rogers 2014). Other measures brought to bear included: (1) drainage of pools within a radius of a hundred yards from dwellings; (2) admixtures of oil and kerosene as larvicide that coated swamps; (3) prophylactic daily doses of quinine made available at dispensaries. Statistics fructified these concerted efforts as hospitalization rates from malaria declined sharply between 1905 and 1909 from 9.6 percent of the workforce to 1.6 percent. Where deaths mounted each month from yellow fever by 1906 only one non-fatal case emerged for the entire year. Under Gorgas’ residency the bête noire of pestilence appeared to be all but eradicated. The sea change placated the public relations fiasco ginned up by the fourth estate back home and by 1913 the tide of disease was stemmed insofar as 5.2 deaths per thousand were recorded (Maurer and Yu 2023).

The seminal public health policies on the isthmus curved the bacchanalia of death where once the Canal stood on the precipice of failure. Within the firmament of construction a symbiosis between epidemiology and engineering is seldom seen whose absence in this case would have conduced to a French redux of futility. Whether by machine or microbial mitigation success on the Canal hinged on the mastery of nature that defied human control for millennia. At the dawn of the 20th century President Roosevelt’s industrial policy reversed this longstanding status quo as a testament to America’s preeminence. Akin to a palimpsest the project went on to domesticate the jungle where once this notion bordered on the realm of science fiction. The saga of the Canal therefore bears the hallmarks of engineering just as much as epidemiology. If the lifecycle of the Anopheles and Aedes aegypti mosquito was not disrupted it is dubious if the Canal would have ever seen the light of day. What made matters untenable was how in the incipient stages the Canal became tantamount to a lottery of death. The scare from an invisible foe brought work to a standstill. Were it not for the draconian interventions the flight of workers would have continued unabated. Until and unless Gorgas hedged against disease the Canal could not proceed.

0 notes

Text

Macaroons versus Monster Trucks

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities, 1859

Other than the divergence from the myopia of prying apart the isthmus with a sea-level canal Washington also bested its fleur-de-lys counterpart with superior technology. The suite of machinery in America’s inventory had a material effect on the alacrity with which regolith and rock was removed from the bed of the waterway. Mythologized as a Goliath of steam and steel the Bucyrus dragline weighing ninety-five tons weathered the wear and tear of construction for a decade as it bent nature to its will. Sporting a bucket to accommodate five cubic meters of spoil with each bite into the ground and whose efficacy boasted a fivefold increase in productivity versus any French copy the machine expedited work by orders of magnitude (Parker 2009: 464). An army of these giants sitting atop rail tracks led the mechanized assault on the 50-mile trench together with a phalanx of trains in the vicinity of 160 each day which hauled the muck out to build the Gatun Dam. This grist sourced from the dig impounded an artificial lake that would later feed the lock system with a steady supply of water to make the Canal’s passage uninhibited. The bespoke Bucyrus made uniquely for this project pared down labour-intensity when the behemoth manipulated 4,800 cubic yards of material each day bereft of protracted downtime (Ryckman 2018).

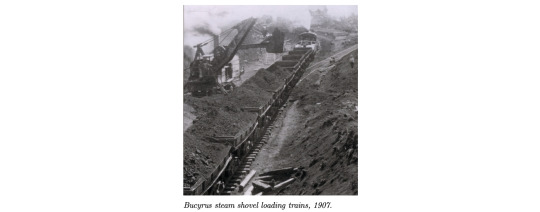

Seven shovels of earth filled a rail car in under ninety seconds or forty-five minutes for a whole train whereby locomotives were kept in perpetual motion when each outbound trip greeted an inbound one (Rogers and Magura 2018). Such continuous kinetic energy militated against any gridlock which might cripple the venture’s lead time. This cavalcade of twenty buckets on four wheels that vacated ground zero took two hours to complete a circuit between the dumpsite and worksite (Giroux 2014). As the railroad expanded piecemeal into the inhospitable terrain a slight gradient always exploited gravity to help the departure of trains laden with rock and rubble. This innovation equally allowed for drainage to keep the roadbed dry for the maze of tracks crisscrossing the Panamanian jungle. Where the French most acutely erred was in their logistics which saw a mismatch between the mounds of earth removed and their disposal. By contrast Chief Engineer John Stevens devised 450 miles of railway akin to a Jackson Pollock painting of lines zigzagging the geography to move dirt apace with the brisk clip at which it was dug (Keller 1983). Automobiles were alien to this world as man and material moved exclusively by the monopoly of rail. A robust network for egressing detritus from the Canal was not an afterthought this time around.

Over the life of the project seventy-seven Bucyrus and twenty-four Marion shovels laboured tirelessly on cleaving a path through the wilds of Panama. In tow with these metal workhorses were track-shifters that exhumed old rail and plopped it down anew as the ensemble of men and machines invaded deeper into the thicket of jungle. The genius of plying trains this way to scaffold the Panama Canal lay in the relentless momentum when a dozen men partook in the migration of track with haste versus the six hundred under past French fiat. Such innovation crimped labour and time to maximize productivity as idleness was anathema to progress. The systematic use of rail in the supply chain equally gave vent to a nocturnal character where by day the drums of industry boomed and by night a bouquet of workers commuted onsite and tended to the machines for repair and restock of coal. Things were always astir and never asleep. The lion’s share of controlled demolition also coincided the evening hours or midday breaks when the flight of personnel transformed worksites into a tabula rasa for Dupont dynamite. Thirty-six years after Alfred Nobel unlocked the power of nitroglycerine this substance evolved into the sine quo non of operations insofar as sixty-one million pounds of it blasted asunder the isthmus (McCullough 1977).

The Canal emblematized the jewel of empire when the might of industry descended upon this barren strip of land. As America rode the crest of the Industrial Revolution amidst the heyday of the Gilded Age with mechanical juggernauts of great calibre the project hurried along in earnest. The Cartesian method of excavation proceeding in lockstep with disposal across a constellation of fixed capital was the single most salient innovation. Pneumatic drills amongst this lot further guaranteed time was a commodity well spent which the economies of $22 million below final budget estimates evidenced (Rogers 2014). Compressed air plants of vast dimensions attended to these rigs whose boreholes at a maximum depth of fifty feet accommodated strings of dynamite. Over 725 of these contraptions perforated the landscape to fracture stubborn rock. Both churn and well drills powered by coal counted themselves amongst the company of tools used along the route as well (Giroux 2014). A choreography of diggers, blasters and haulers thereby manifested into the mainstay of this gorge linking the Atlantic and Pacific. For a measure of perspective more explosives found use in the throes of this project than the sum from America’s wars hitherto. The efficiency wrought by dynamite was made famous in the Culebra Cut.

For the Americans just as it was for the French this nine-mile stretch of dirt hung the Sword of Damocles over the Canal’s prospects. A quarter of expenses or $90m financed this chapter of excavation alone (Rogers 2014). Heavy rains waterlogged the site which landslides compounded by engulfing the lowest-hanging fruit of equipment too ponderous to escape. What made this tranche of work most daunting was the heterogeneity of soil. The unstable geology of soft shale coupled with sandstone at the Canal’s highest elevation wrought havoc on the exigency to remove 96 million cubic yards of material from the Continental Divide. In fact this very conundrum which defeated the French a decade prior would spur the creation of the Bucyrus steam shovel in its 95-ton and 105-ton incarnations as a sui generis remedy to the spectre of failure. Bref the Americans simply engineered the problem away. Whereas Paris sought to cross the isthmus with a minimal amount of digging the buccaneers in Washington set upon doing the most. The former being partial to minimalism and the latter plumping for maximalism evokes the popular stereotype of the disparity in preferences for either country: a dichotomy of macaroons and monster trucks. Facts do countenance this bon mot since France cleared 78 million cubic yards versus the 246 million by the Yankees (Herndon 1977).

0 notes

Text

The Monroe Doctrine's Panama Canal

Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.

Theodore Roosevelt, 1901

America succeeded where France failed in excavating the Panama Canal as the latter stumbled upon financial ruin with $287m in funds haemorrhaged and 22,000 lost souls (Ameringer 1970). The initial follies of this white elephant with its pecuniary overruns and human tragedy was symptomatic of hubris when architect Ferdinand de Lesseps had recently been canonized for his iconic Suez Canal in the twilight of the 19th century. Unbeknownst to the Frenchman however was how the jungle proved far less forgiving if not outright sadistic between the scourge of tropical disease and logistics. The learning curve for the Panama Canal differed from the Suez Canal in that the first was much steeper relative to the benign desert whose excavation took place at sea-level. Furthermore a jungle’s habitat incubates malarial and yellow fever vectors as in mosquitoes which only exacerbated woes like landslides most prominent in wet seasons. Equipment quickly succumbed to the cancer of rust from humidity or the bog of mud (Hook 2010). Workers fared no better as three out of every four engineers embroiled in the snafu perished to disease within a few short months upon arrival. By conservative estimates five hundred lives were sacrificed for every mile of the canal built (Parker 2009). From the outset this monument to empire was accursed.

When France debuted its star-crossed project in 1881 until its premature end in 1889 the method of construction encountered a litany of problems. The single biggest fault in a constellation of them hinged on the preference to dig a sea-level canal versus one governed by locks. Blinded by accolades from the Suez Canal engineers sought to recycle past know-how and extrapolate it wholesale onto Panama’s geological map. In the absurdity of such logic it never occurred to the Pollyannas that a mind-numbing amount of earth would need to be excavated. Moreover if the tolerances of slopes were not minded then landslides could become a thing of habit. The latter did manifest. Not only was a sea-level anatomy a great fiscal burden its design also begot a minefield of complications from the inherent instability of soil. Although locks were added later to the architecture’s plan in 1887 a gratuitous waste of money had already aroused skepticism for the project hence hubris doomed it from the start. Lessons from triumphs of old across the sand dunes of Egypt bore no resemblance to Panama’s topography (Bonilla 2016). Upon taking the helm in 1903 American engineers adumbrated in a meticulous study that a sea-level canal was so outlandish its costs would have exceeded one with locks by $100m in tandem with a ten-year delay (McCullough 1977).

The Icarus syndrome afflicting the French had much to do with a lack of deference for geometry which in turn blighted their gambit of vicariously attempting godhood in bridging two oceans via the Isthmus. Because a sea-level canal was prized the subsequent cut had to reach an incredible depth as it would need to taper off with a shallow gradient to eschew landslides. The nemesis of rainfall endemic to the region however made it abundantly clear that the angles chosen would destine any work to be in vain since excavations were refilled just as quickly as they were dug. A run-of-the-mill project deteriorated into a Sisyphean task when floods wrought havoc on worksites by turning them into a sodden mess. This misadventure brought forth by miscalculation from the parochialism of insisting on a sea-level canal led to an ever faster depletion of resources as cash reserves in Paris dwindled. Ferdinand de Lesseps simply could not be moved from his brash notion of terraforming the Isthmus in spite of how the attrition of wasted time claimed more lives by the day when disease terrorized the workforce. In all fairness upon Americans resurrecting the project they too were intoxicated by a sea-level canal in the incipient stages but averted disaster by the narrowest of margins when the Senate voted 36 to 31 for locks (McCullough 1977).

Blessed with the luxury of hindsight the cautionary tale of France’s ignominy ensured the project would not be abdicated anew. The next chapter of the saga began when Columbia reneged on the Hay-Herrán Treaty promising Washington a lease over the Panama Canal Zone. When the latter did not take kindly to this effrontery the stick substituted for the carrot as America militarized Panama on its quest for independence. In the spirit of the 1823 Monroe Doctrine which sought to make a protectorate out of the Western Hemisphere the ribbon of land soon fell under the prerogative of President Theodore Roosevelt after the yoke of Columbian rule was cast off. Upon ratification of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty in November of 1903 ownership of the real estate stretching fifty miles across the isthmus was formally transferred at the cost of $10m and $250k in annuities henceforth (Connie 2012). Panama ceded the Canal Zone in perpetuity as recompense for the gun-boat diplomacy that was brought to bear when the USS Nashville shored up deterrence against Columbia’s tit-for-tat through its proximity to the coastline. With such realpolitik put to rest this patch of land which proxied for a de facto outpost of American imperialism saw work begin in earnest. President Roosevelt thus inherited the defunct Panama Canal.

Unlike the brinkmanship of the French the esprit de corps for the Canal under American stewardship evoked much more intensity for it was an existential matter. Whereas private capital financed the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique it was the Treasury which shepherded the project in its entirety as it incurred $375m (1910 USD) in costs. Such statism was a function of the Progressive Era when pundits and technocrats subscribed to a larger role for government. Hence President Roosevelt would couch the infrastructure in the firmament of industrial policy for two red-letter reasons: (1) proffering a gateway of a 11,700-mile shortcut for commerce between New York and San Francisco (Lesseps 1886); (2) remedying the impasse of the isthmus that divided the Atlantic and Pacific theatres to the detriment of deployment. The Canal was equally esteemed for diplomacy in the Asia-Pacific region when Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines were seized as spoils of conquest following the 1898 Spanish-American War. A strategic artery spanning the isthmus that transcended its utilitarian function could therefore consolidate territorial possessions for overseas imperialism. Seen through American exceptionalism the Canal became a physical expression of empire.

0 notes

Text

Children of Hamiltonianism-Keynesianism

The burned hand teaches best. After that, advice about fire goes to the heart.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, 1954

For couriers with the gumption to haul mail overland by horse from one side of the continent to the other the trip would be braved over forty days atop pockmarked roads of poor quality (Kemble 1938: 11). Albeit until 1858 all mail delivery would be left to the exclusive province of steamships the horseback Pony Express brought to the fore in 1860 lasted only a single year before being prostrate with bankruptcy. By contrast boats halved the journey with a cargo capacity beyond compare as their nautical bridge transported a staggering amount of goods and passengers in service to westward expansion. It was the happy accident of the Gold Rush entreating fortune-seekers who were spellbound by California’s Eldorado which paid rich dividends to the Pacific Mail and United States Mail companies. Business for the former swelled with such alacrity it compelled the firm to establish an engine foundry of behemoth size in what was erstwhile the sleepy San Francisco Bay (Chandler and Potash 2007). Coal stations sprung up at waypoints all the while the company built a forty-seven-mile railroad to expedite the trek over the Panama’s Isthmus which began service in 1855. Two decades on from the Pacific Mail’s founding did the Panama route account for half of the rush of humanity who sought California’s friendly climes (Kemble 1938).

The industrial policy subsidizing steamships had partly to do with the geopolitics of the time as well. Territory was ceded as concessions inked in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo amidst the postbellum year of the Mexican-American war. The prevailing winds of Manifest Destiny saw the land acquisition of 525,000 square miles under this modus vivendi in 1848 transferred from the Republic of Mexico to the Union (Suarez 2023). The magnitude of this annexation was on par with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 when Napoleon Bonaparte who was in dire need of funds for his looming conflict with Britain relinquished France’s stake in the New World (Cowen 2020). In fact so alike were these two transactions that a symmetry of nominal terms existed since America procured both swathes of land for the identical amount of $15m each. Therefore with the advent of steam propulsion making the caprices of wind for sails outdated the opportunity was plumbed to link the eastern and western coasts. As if by providence the gold soon discovered in Sutter’s Mill at the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains was a coup de foudre for statesmen whose steamship subsidies would broach nationhood as much as it was about mining gold. A species of symbiosis emerged between the geopolitics of colonizing the West and partaking in its bonanza.

Bringing distant markets together by plying an artificial duopoly between the Pacific Mail and United States Mail Steamship Companies set a standard to replicate. The legacy of selecting champions to spur economic development would be a lodestar for future statecraft. Whatever industry was held in abeyance in virtue of less than ideal conditions would be remedied by government favouritism. Observe how the prototype of steamship subsidies inspired the railroad duopoly between the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific Railroad Companies as codified by the Pacific Railway Act in 1862. Observe the oligopoly of domestic airlines between the TWA, United Airlines, American Airlines and Eastern Airlines which owed its provenance to the 1925 and 1930 Air Mail Acts. Observe how Pan American Airways monopolized foreign travel courtesy of the Foreign Air Mail Act of 1928. Each of these vignettes were wrought by industrial policy in specific instances where economic liberalism could not enter the fray when beleaguered by unmitigated risk. The bespoke solution to this market failure invoked government as a lender and guarantor for a subset of companies whose position could foster the industry until firmly established. Contextualizing steamship subsidies throws into relief just how seminal this policy was.

Unlike the sail-driven predecessors operating costs were too prohibitive were it not for the grace of statism. In fact American subsidies would be gleaned from the practice of Victorian Britain’s Cunard Line which Parliament underwrote and whose largesse was reciprocated with mail service across the Atlantic. The Union’s mimicry of this market intervention helped defray costs apportioned to the upkeep of these seagoing leviathans. Engines, boilers and four-hundred tons of coal accounted for well-nigh half of gross tonnage and provisions parcelled out for the multi-week trip further added expense. The real limiting factor lay squarely in the law of diminishing returns insofar as early steam technology failed to generate dramatic gains in speed commensurate with a ship’s stockpile of coal. A voyage at 10 knots consumed 37.75 tons daily whereas 12 knots saw a twofold increase of intake at 65.25 tons just for that little extra pickup. The scores of coal depots scattered along the route for layovers somewhat attenuated the profligacy of fuel but this fiscal bête noir was not so easily dismissed. In little time did the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s annual subsidies rise by 58 percent from $190k to $348k in adjusting for these logistics. The outlays were nevertheless worthwhile as they funded circa 30,000 missives departing on each trip (Chandler and Potash 2007).

Detractors are not erroneous in their persuasion that government subsidies are liable to distort market forces but the alternative is no better. Naturally the perennial debate between classical supply-side economics and Hamiltonianism or Keynesianism is appropriate since no single remedy has universal application. Yet it is irrefutable that just the right amount of monetary stimuli can kickstart whole industries whose existence would have otherwise fallen into oblivion. A catch-22 thus emerges: to have something by hook or by crook versus having nothing at all. Where a vacuum exists when none dare to create industry the treasury can be the progenitor of enterprise to offset risk. Underinvestment epitomizes the death knell for great projects which have floundered. America’s steamships manifestly lend credence to this proposition as the darlings of subsidies like the Pacific Mail and the United States Mail Steamship Companies precipitated a good deal of development. Perhaps perfect competition might have been defenestrated as the duopoly crowded-out competitors in its coastwise service yet the truism remains that the endgame begot a bevy of benefits for the country (Kemble 1933: 407). Before railroads would usurp this preeminence the Union could now penetrate remote lands where riches lay.

0 notes

Text

Mining Gold with Mail Subsidies

All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, 1954

The maritime sector was equally held aloft by industrial policy in the shape of contracts for sea captains to make a routine of servicing ports regardless of whether their boats were laden with goods. These crafts would be christened ‘packet ships’ for hauling mail to their destinations in acquiescence to a strict schedule. This quasi-public procurement authorized by the 1845 Act of Congress saw firms enter contractual agreements with government to sail with regularity between cities as the heralds of news and the bringers of goods to populations that would have otherwise been left oblivious to the goings-on of the world. This early form of correspondence was a manifestation of Congress consolidating nationhood through the bilateral trade of distant cities. Prior to this seminal piece of legislation meant to subsidize the steamship industry packet lines had long been tasked with plying the waters between New York, Liverpool, London and Le Havre on transcontinental routes. Departures hewed to high standards of punctuality unlike previous norms when the weather and clime dictated the days for setting sail. Packet lines put America on the path towards industrialization early in its formative years since the clockwork flow of trade that ensued left no scintilla of idleness from an ad hoc calendar to hamper commerce.

The first industrial policy in a series of them to seed the steamship sector bestowed authority upon the Postmaster General to unilaterally recruit ship outfits for mail service. Before long this mandate by itself proved toothless to bootstrap growth when the full spectrum of government patronage was required in what was to be a zero-sum game of curating winners. It behooved Congress to mount the financial backing for a few handpicked companies if the venture had any likelihood of success despite the appearance of crony capitalism when some firms were to be forsaken of such strategic investment. This plank was perforce a function of two imperatives: (1) increasing the fleet size of steamships that would be repurposed in the event of war for the Navy hence the appellation of quasi-public procurement; (2) the unification of California and Oregon with the rest of the country. Likened to a centripetal force the 1847 Act of Congress culminated in the creation of postal routes snaking along the Eastern Seaboard off the continental shelf to link major cities from New York all the way to Astoria in Oregon. The advent of steamships emblematized the sine quo non of America’s Manifest Destiny whose Weltanschauung called for the colonization of geography in short order to make way for a national identity. Westernmost states would no more be left unmoored from the workings of the young nation.

Vast distances fragmented the American body politic in the mid-19th century whereby bringing the West Coast into the fold of the Union took precedence. What better method to actualize this lofty ambition than by a transcontinental link on water as a precursor to railways. California’s charm for statehood lay in its auriferous topography that beguiled a cottage-industry of miners amidst the Gold Rush. Oregon’s wilderness on the other hand was extolled as Eden for its fertile lands when homesteaders Americanized the West. The 2,170-mile Oregon Trail fraught with perils would cement the country’s sovereignty over the frontier. Upon the judicious use of industrial policy what came to manifest were broad implications where in one respect shipping boomed and in the other gold operations saw gains from speedier supply chains. The federal government’s repudiation of laissez-faire economics in this instance from its proper patronage of the maritime industry became integral to America’s development. In 1847 the Pacific Mail Steamship Company was conferred a ten-year mail subsidy of $190k per annum to ferry goods from the western shore of Panama’s Isthmus onto California and Oregon. The eastern leg of the journey would be manned by the United States Mail Steamship Company which was granted $290k each year (Bacon 2023; Kemble 1949).

Since this expedition preceded the Panama Canal’s arrival by fifty years the umbilical cord that bound the East and West Coasts was sundered in two giving a wide berth to the lengthier journey around Cape Horn. The sixty miles of the Panama’s Isthmus would instead be overlanded by argonauts and mules alike as a land nexus for the two discrete routes. Wet seasons saw canoes being commissioned along the Chagres River to make the journey less arduous. Upon embarking a second boat destined for the terminus the trip could then be completed in its entirety. Subsidies earmarked for this endeavour were lifelines for steamships bereft of which the budding industry would have floundered in the absence of such fiscal injections. When economic viability is marginal as it belies the law of supply and demand it is at this juncture where industrial policy’s merits reveal themselves. If risk exceeds reward no investor of sound mind would partake in the adventurism where liabilities are too great. If a company is projected to operate at a loss or at a break-even point without having some purchase on profitability within a reasonable time horizon then no amount of capital investment could be justified. In the vignette of steamships their profit margins would have been mediocre if not non-existent were subsidies forfeited.

Behold the ledger where an average trip to Panama for the Pacific Mail Steamship Company from the West Coast approximated $38k of which $35k was recouped from passenger revenue. Within spitting distance of solvency it was only with the addition of mail subsidies that a salubrious buffer of profit was purveyed as a source of income. Later in 1876 the value proposition of passenger and freight service cleared well above the threshold of yearly expenses by $60k where government succour made the whole venture that much more lucrative (Chandler and Potash 2007: 34). It was Congress which thereby midwifed the steamship industry, kindled the Gold Rush upon streamlining supply chains and united the country in one fell swoop. By discarding entry barriers to markets the government made conditions more amiable where opportunity costs would have been too high not to jockey for the chance of being a first mover in the industry. No longer were steamships mere curiosities but rather they were held in greater esteem after having wed New York to San Francisco in a thirty-five-day and later a twenty-one-day trip (Kemble 1938). No sooner did the duopoly of steamship companies sail its maiden voyages along the two routes that the Gold Rush caused a frenzy of demand for transport between the Pacific and Atlantic seaboards.

0 notes

Text

How the West was Won

The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever.

Jacques Yves Cousteau

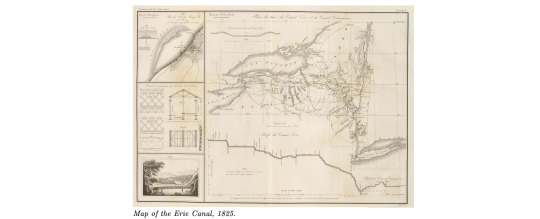

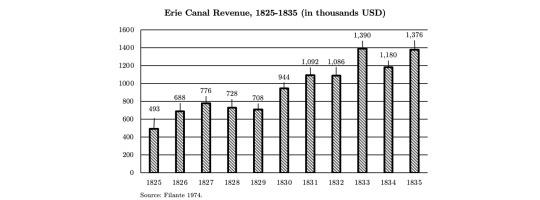

Isolationism disembodying the interior into economic silos from the rest of the country was subverted by the Erie Canal which cut travel times from six weeks to a mere six days. With this quantum leap in transportation a population bomb tripled the census of inhabitants residing in primary cities adjacent to the corridor between the Hudson River and Lake Erie (Morganstein 2001). Urban agglomeration changed cities like Rochester and Syracuse into epicentres of industry overnight. Without delay a tenfold decrease in the cost of logistics kindled the exponential growth rate of industries downstream both literally and figuratively as commodities flowed downriver and finished goods went upriver. The Industrial Revolution’s pedigree was unambiguously sourced in the wellspring that was the Erie Canal which reified Alexander Hamilton’s tenets informing the era’s beginnings. Dogged by malarial swamps and dense forest this artificial river would be cleaved through the wilderness upon the solicitation for an army of 50,000 hard men who laboured on the megastructure. Scrutiny over the schematics throws into relief the sheer scale and scope as unprecedented since they approached thirteen times the length of America’s longest canal whilst outdistancing the country’s combined stock by a factor of three (Koeppel 2009).

The industrial policy could be rhapsodized as nothing short of a runaway success given that it shepherded the country into modernity. This effusive adumbration is no hagiography when half of all the aggregate traffic across such purpose-built waterways traversed the Erie Canal (Ransom 1964). If a proverbial Big Bang for America’s industrialization does exist it would be none other than the nexus bridging New York’s namesake city with Buffalo. Effectively the canal personified a workhorse for the Northeast monopolizing freight when railroads in the main serviced the market’s segment of passengers (Filante 1974: 101). As supply chains of old exploiting beasts of burden fell into obsolescence a domino effect was engendered whereby regions discovered they could maximize their comparative advantage. The Midwest exported ever greater numbers of raw materials juxtaposed with the industries in the East which churned out manufacturers en masse. The prohibitive costs that predated the Canal were barriers to trade but upon the Erie Canal’s inauguration businesses began to use less of their bandwidth on outlays for shipping and paid more heed to their productivity. The shrinking of time and space through the scale economies of transportation allowed for the prolific yields of foodstuffs and merchandise.

Spatial economics of this kind conduced to the spate of urbanization and industrialization by vanquishing the ‘friction of distance’ (Janelle 1969). Where vast sums of money would have been spent profligately upon onerous supply chains now these same funds could be shrewdly ploughed into capital investments to produce at scale. With the region no longer balkanized into pockets of industry the rapprochement signposted the beginning of America’s renaissance prior to its take-off into the pantheon of great empires. Shipping costs were no longer gatekeepers for markets whose newfound accessibility heralded an open invitation to firms previously ostracized. Under the aegis of industrial policy it came to pass that capitalism was finally unbridled to fill the void of commerce where one had long existed by tapping the magic inherent in the law of supply and demand. All roads lead to Rome or in this case New York City since the Erie Canal’s market integration mothered the explosion of migration into the cosmopolitan metropolis and elsewhere. Between 1820 and 1850 Rochester witnessed an influx of 35,000 townsfolk; Buffalo welcomed 40,000; nearby Lockport saw 9,300 homesteaders; and New York City burgeoned to half a million from 200,000 (Shaw 1966: 263). The prospect of prosperity was a siren call for settlers.

As the parameters of transportation were redefined a sea change in production revolutionized the economy where volume was suddenly king. Fifteen years out from the christening of the Canal the wheat output reaped from the Erie basin soared from 14,000 to 8,000,000 bushels for consumers awaiting such fare downstream (Shaw 1966). By democratizing markets the Erie Canal incentivized the tilling of more acreage together with sounder agronomic techniques of horticulture so that supply may align with demand. These farming methodologies descended from opportunities unlocked by the cost efficiencies of waterborne transportation that no longer hinged on fair weather or topography as did land carriage. Equally the conveyance of timber by this man-made river was imparted no less of an advantage where jerry-rigged rafts hurried it to sawmills for processing (Koeppel 2009: 266). Although these clumsy contraptions exasperated boat captains who took umbrage at their improvised construction which slowed traffic the new affordability of lumber meant furniture and dwellings could be traded with more abandon than before. A construction boom resulted and the halo effect beguiled others into the development of infrastructure such that by 1850 over 4,000 miles of canal were built at a rousing cost of $300m (Harrison 1980).

The hydraulic highway of the Erie Canal that slowly lifted or lowered ships to their destination in lockstep with the elevation differences between Buffalo and Albany birthed industry and its trappings of granaries, mills and foundries across the Northeast. Rochester earned the epithet of ‘Flour City’; Syracuse was bestowed the moniker ‘Salt City’; and Troy contiguous to Albany was dubbed ‘Collar City’ for its sartorial monopoly. Further east at the terminus of the canal in New York City factories and docks were brought to life as human capital of all stripes converged on this boomtown. Two-thirds of American imports and one-third of its exports left and entered the city respectively not long after the Canal’s completion (Albion 1984). An a posteriori analysis reveals a parity of commercial activity between New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore but this evenness petered out once the Great Lakes were bound to the bosom of the Hudson River’s leading port. The Canal was analogous to a black swan event where firms abruptly took the liberty to divert their business that irrevocably changed the status quo. The New York Port had already seized the coveted ‘packet lines’ or mail service by ship and the ‘Cotton Triangle’ of cash crop plantations in the South connected to Britain’s mills and Africa’s slave trade but it now also annexed the Midwest (Wheeler 2009).

0 notes

Text

The Erie Canal

Good roads, canals, and navigable rivers, by diminishing the expense of carriage, put the remote parts of the country more nearly upon a level with those in the neighbourhood of the town. They are upon that account the greatest of all improvements.

Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 1776

The zeitgeist of nationalism fostering the ascendancy of the Merchant Marine between the Tonnage and Lighthouse Acts from the selfsame vintage in 1789 crescendoed into the famous ‘Report on Manufactures’ two years later. This polemic propounded by Alexander Hamilton who was an early exponent for a mixed economy with some influence of statism upon free markets sought to remake America from an agrarian into an industrial society. As an iconoclast he espoused the belief that statecraft could incubate a Cambrian explosion if government elected to play a bigger custodian in the country’s development. With robust industries ascribed to tariffs and subsidies America might begin to disentangle itself from colonialism’s legacy in a bid to assume autonomy. Such policies of market interference were anathema to the orthodoxy of the day when economist Adam Smith had authored his iconic apologia for the invisible hand of laissez-faire capitalism in the ‘Wealth of Nations’ only fifteen years prior. At the same time the literati looked askance at all centralized power upon having just defeated the British monarchy under the banner of individual liberty. Nevertheless the Hamiltonian doctrine admonished that if not for an interventionist state infant industries would be deprived of growth in perpetuity.

Limited government simply emboldens more established incumbents to purloin what little marketshare might be used to nourish younger companies. Fatalism characterizes all possible outcomes thereafter since any manufacturing base would be stillborn if vulnerable firms were left to their own devices. A dirigiste variant of governance with a predilection for protective tariffs and federal subsidies by contrast could be a standalone buffer against the asymmetrical advantage held by foreign firms. Reprieve from such intense competition would be enough of fertile ground for fledgling industries to become self-sufficient. Hamilton’s thesis really did emblematize a clarion call for the country to transcend its primordial ways of husbandry by finding deliverance in a diversified economy. Therein the manacles of colonial subservience could be broken if firms were insulated long enough so they may scale up through the accumulation of capital and technology. This judicious use of policy was the ideal antidote against the capture of indigenous industries from the exploitation of foreign firms operating with impunity. Although the logic of this statecraft was a radical departure from the traditional precepts of free markets a whole conceptual edifice was eventually built around it with the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

The manifesto of the Report on Manufactures was manifestly the progenitor of the country’s early development. What coincided with this new regime eponymously dubbed the ‘American System’ that came into mainstream acceptance due to the maverick Henry Clay was a gamut of industrial policies whose stimulus saw factories abound. The monoculture of agriculture production incrementally took less precedence with manufacturing growing at a faster cadence ex post independence. A consensus soon emerged of how a strong central government might very well be the gateway to an America becoming a juggernaut of industrial strength. Likeminded thought leaders thus began to form a critical mass of opinion in favour of a more proactive posture in markets. On the eve of the Report on Manufactures the Patent Law of 1790 was equally amongst that same array of policies in the camp of statism protecting know-how from pirates who would otherwise sabotage growth. In this case the latitude of having a temporary monopoly over new self-made technologies for fourteen years was a boon to companies seeking profitability (Frederico 1936). Henceforth inventors boasted the right to profit from their creations as they were immune to imitations whilst America ratcheted up its industrialization in earnest.

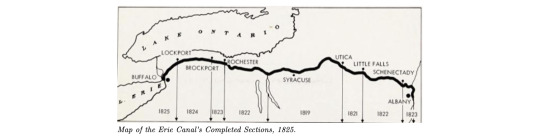

What the ‘American System’ inherited as the progeny of the Hamiltonian doctrine in the wake of the War of 1812 was a trinity of nationalist policies: (1) trade protectionism; (2) a national bank to stabilize the dollar in times of distress; and (3) industrial policies providing the wherewithal for public infrastructure. The third funded America’s first marvel of engineering linking the Hudson River with the Great Lakes so trade may seamlessly pass through the region. In lieu of the federal government it was the New York State Legislature which bore the onus of allocating money destined for this gambit. By the end vast tracts of land totalling 363 miles was excavated after nine years of laborious effort at a substantial cost of $7m or $166m after inflation that saw America’s rapid industrialization (Utter 2020). Such a mammoth piece of infrastructure cemented New York City’s station as America’s premier place of business by reconciling the hinterland with the Empire State. Raw commodities from the breadbasket of the Midwest came to be ensconced in the teeming markets across the Atlantic seaboard. Iron deposits sourced from this Elysium of minerals equally supplied the panoply of foundries and steel mills in the East. The economics of waterways would eclipse overland routes by orders of magnitude (Bowlus 2014).

The completion of inland navigation via the Erie Canal between 1817 and 1825 from Buffalo to Albany with a total of 83 locks pared down shipping costs by a precipitous 90 percent. This vertiginous decline from $100 per ton of freight to a pittance of that at only $10 was a revolution for America’s supply chains as boats with a capacity of sixty tons superseded wagons drawn by quadrupeds whose pathetic limit was a single ton (North 1900: 123). Since waterways relegated overland shipping to an anachronism the cost difference between the two was so considerable that higher tolls could be added without being exploitive. In the first year alone did the Erie Canal amortize half a million dollars of its cost from the provenance of revenue generated from operations. Even with the stepwise growth of railroad expansion the throughput of tonnage by water appealed to merchants much more than that of locomotives despite the latter’s speed (Filante 1974). Far from being a flight of fiscal folly this investment in infrastructure ignited a mania for economic activity from the American interior to the bay of New York City. Where once eye-watering freight rates prohibited industrialization now the calculus had shifted to encourage the scale economies of production. Cheap transportation was in vogue.

0 notes

Text

The Public Good of Lighthouses

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters. And God said, 'Let there be light,' and there was light. God saw that the light was good, and he separated the light from the darkness. God called the light 'day,' and the darkness he called 'night.' And there was evening, and there was morning—the first day.

Genesis 1:1-5

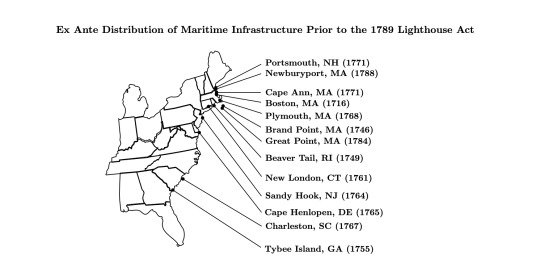

Concurrently when the Tonnage Act was legislated Congress took it upon itself to federalize the upkeep of maritime infrastructure to avert mishaps over treacherous waters. The Lighthouse Act of 1789 was one such piece of industrial policy that sought to correct the patchwork of authority informing the critical scaffolding of assets like beacons and buoys across shipping routes. Navigational aids like the foregoing were part and parcel of maritime trade and it behooved Congress to standardize them in the reduction of shipwrecks riddling the desolate coastline. This consolidation of regulatory oversight not only mitigated insurance premiums with the promise of passage unmolested by hazards but it equally unified disparate regions under one cohesive market. Economic homogenization of this species meant sea voyages were more economically viable now that government paternalism placed a greater currency in the minimization of risk for seagoing vessels. Far from a cynical gesture of bureaucracy this formative measure militated against losses and accidents for boats frequenting American ports with infrastructure now in the province of government fiat. Also it was the case that lighthouses were seen for more than their utilitarian function since a network of these structures might be the sinews of nation-building.

The spectre of division from the unique interests of so many states at cross-purposes with each other was allayed by this system of uniformity that bore the fingerprints of federal lawmakers. Amongst the thirteen lighthouses predating the Act alongside the Eastern seaboard it was the one on the approach towards New York City in Sandy Hook whose form factor was espoused for future towers. Expenses were not spared for the battery of new lighthouses to follow as they were to be expressions of the power vested in the federal government and thus their longevity were of great import. The archetypal design consisted of stones laid down in an octagonal shape that offered resistance against the windswept coast which rose up seven flights of stairs to reveal an oil lantern at its summit (Miller 2010: 26). Because these freestanding structures spoke to the national interest of maritime trade just as much as they were about saving property and lives it fell upon Congress to spearhead the whole project. More often than not these monuments to government signalled a mariner’s proximity to a harbour as a landmark for the sake of expediting transit rather warn of nearby reefs where few existed. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton invariably was the protagonist in this saga since he was the architect of these towers in the wake of the Act.

Lighthouses with their spartan appearance echoed the utilitarian aesthetic of the Republic unlike France’s own ornate proclivity bespoken by the Cordouan specimen fit for a king near Bordeaux. Instead for America’s sensibilities form followed function and the constellation of these cyclops made of stone were of special use to project power at night when foreign ships could spot their light from afar in a show of strength according to lawmakers. So diplomatic dividends were recouped just as much as economic ones from this industrial policy of infrastructure. But why was it so befitting for the government to arrogate to itself the provision of these buildings rather than leave them to the laissez-faire spirit of private markets? The answer here actually evokes the rationale behind the state being the author of public infrastructure more generally where businesses might fail. As economist Ronald Coase (1974) monographed in his seminal treatise titled ‘The Lighthouse in Economics’ these structures that hold vigil over waters are public goods. The benefit rendered in the form of light is neither excludable nor rivalrous meaning all mariners within range may use it for navigation without impinging on its availability for others. In economic theory a revenue model would thus be impractical to collect fees for what is otherwise termed a classic 'free-rider dilemma'.

Essentially the prevalence of parasitism means all seamen may steer themselves into safe harbours courtesy of lighthouses atop bluffs regardless of whether they paid for them. Since homo economicus maximizes his self-interest the suboptimal outcome would be the undersupply of such structures in the absence of revenue as no one would voluntarily finance their construction and upkeep. The only remedy to this free-rider conundrum fraught with users shirking costs which economist Mancur Olson (1965) noted is to collectivize the infrastructure under state control through taxation. By dispensing with voluntary payments where individual rationality would have led to collective calamity as shipmasters were left liable to shipwrecks it is only by government coercion that safe traffic could be reconciled with taxes. Subjecting all actors to these costs mitigates the inequity inherent in a system more atomized where individual interests might trump group interests. In the wake of the Lighthouse Act signed into law by President George Washington the sustenance of this infrastructure thereafter was borne collectively by the nation’s federal treasury. Where private investment was once parsimonious the grim regularity of lost ships and lives came to be arrested by government dirigisme with twelve new towers proliferating in the 1790s (Bruce and Jones 1998).

Chronic underfunding whose outcome saw dilapidated lighthouses like carcasses dotting the seaboard then found its solution in a paradigm shift that nationalized these structures. In the fourteen years between 1791 and 1805 federal expenditure for these buildings as more were added in quick succession burgeoned 137 percent. By 1820 the count had grown to fifty-five from its dearth of only thirteen back when individual states lorded over construction (Noble 2004). A sense of haste was palpable. It occurred to lawmakers that these sentinels overlooking the Atlantic were germane to the maritime industry whose ships laden with goods were the logistical arteries of the nation’s development. What finer way to mark America’s extrication from British suzerainty than for Congress to promise the timely movement of commerce by funding a robust system of lighthouses. A post-Revolution identity began to be forged all the while shipowners would be less beleaguered by the prospect of losing property under the auspices of the federal government. Maritime safety inarguably correlated with shipping costs. Where once infrastructure was fragmented it now fell in the province of a standardized system. This landmark piece of legislation in a prescient way laid a precedent where the state became the scaffolding for other industries in the future.

0 notes

Text

Maritime Nationalism

He who commands the sea has command of everything.

Themistocles, c.525-460 BC

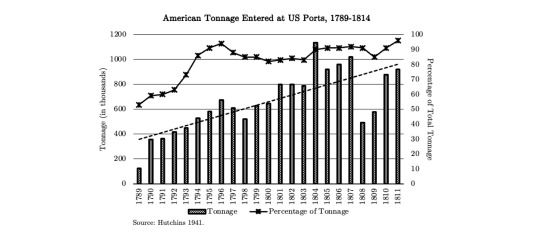

Both protectionism and strategic investment have been mainstays in America’s buildup of its Merchant Marine whether by cabotage or subsidies since its divorce from the metropolitan power of Britain. In the post-independence era statesmen began in earnest to cradle waterborne commerce against the predations of Europe’s many empires in the Mercantilist Age. No longer a captive market or a feedstock of Old Europe the New World of America came to be emancipated from the yoke of subjugation to claim sovereignty once and for all over its proper interests. From that point onward the country would be spared from Britannia’s monopoly. Economic growth so became a function of efforts meant to fructify an armada of ships as the young republic was poised to command the high seas. Seafarers who braved the open waters with the countenance of Congress went on to carve out new trade routes bereft of the previous restrictions prevalent under the jackboot of British colonialism. In fact right in the thick of the Revolutionary War was the Treaty of Amity and Commerce of 1778 negotiated with France to export commodities and import manufactures. Access to French ports gifted America with a ‘Most-Favoured Nation’ status whereby its trade advantages would be as favourable as any other counterpart with such privilege.

This parity in trade relations not only vouchsafed greater autonomy to the fledgling economy through the diversification of markets but it was a fillip to industrial development as well. The influx of capital goods which circumvented both colonial and agrarian dependence quickly became the grist for manufacturing. America’s lowly status as a supplier for raw goods would be no more when the paradigm of exploitation codified by Britain’s Navigation Acts came to be undone. Exports from the homeland thus began to skirt the predatory practices endemic to Britain’s dealings with its colonies. Those prohibitively high tariffs that once hobbled America’s industries gave way to a stronger purchasing power whereby capital accumulation could be more keenly ploughed into investments for machines and factories. This shift of production factors essentially laid the foundations for the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century on the opposite side of the Atlantic. Finally American industries stopped being curtailed when the growing profitability of cash crops were not marauded by tariffs in a stark departure from the mores of mercantilism under Britain (Eckes 1995). This newfound inflow of capital set America upon the path of industrialization whilst its cities evolved into hives of commercial activity.

Industrial policy buttressing maritime trade had an intimate symbiosis with urban growth as the economy matured. Over time a panoply of consequences saw a throng of dockworkers and businesses coalesce around the magnet of shipyards in New York and Boston which epitomized gateways to Atlantic trade. In short order did the copious amounts of cargo to these ports transform them from sedate outposts into the beating heart of America’s industrialization. Like a beacon in the dark the wealth generated here attracted immigrants and migrants alike who in turn changed the profile of these metropolises in indelible ways. It was within this melting pot of people and goods that the Buttonwood Agreement of 1792 emerged which heralded the genesis of the New York Stock Exchange and the creation of Wall Street that was once the physical wall on the periphery of the New Amsterdam settlement (Eisenstadt 1994). The reason why banks proliferated most prominently in New York was in virtue of how merchants and traders availed themselves of these institutions to manage their earnings whereby the financial sector found itself wedded to the maritime industry. Pursuant to the laws of unintended consequences Wall Street was therefore intrinsically a function of New York City’s thriving docks by catering to the nouveau riche.

Around the same time the Tonnage Act of 1789 further cultivated the indigenous maritime industry to run athwart of the legions of fleets from established merchants across the sea. To build, be a proprietor of or operate an American ship was given greater prominence than the scores of vessels registered outside of the territory. The genius of this industrial policy was to proffer a substantial cost advantage to the domestic industry so it may wean itself off from Europe’s hegemony. Where shipbuilding once languished this new incentive by government design beckoned shipwrights to produce at scale so they may remedy the disparity that would follow from American harbours being less hospitable to foreign craft. Those behemoths in the water made at home were subjected to nominal tariffs of only 6 cents per ton whereas others were levied 50 cents for the equivalent mass (Miller 1960: 19). Naturally it became more profitable to ferry goods aboard domestic ships whereby in less than a decade 94 percent of vessels entering mainland ports originated from the Union (Hutchins 1941). Not only did this Act serve as a source of revenue for the federal government but it equally hedged against industry being overwhelmed by European competitors. This stratagem of bestowing preferential rates onto native ship producers aroused the growth of the maritime sector.

By the mid-18th century the fruits of this partiality towards American shipbuilders saw their gross tonnage of craft reach 3.5m only second to Britain’s 3.8m. Where the Merchant Marine acquired their comparative advantage was in the ready supply of oak timber and pine masts that could be exploited to build the variety of barques, brigs, schooners and clippers with gusto (Hutchins 1941: 172). This taxonomy of ships was turned out in large numbers since America prospered from natural endowments of production factors that were scarcely found in such bounty elsewhere. Whilst this deficit handicapped other economies the eastern seaboard was left immune to this affliction of timber famine. It was particularly the fallowed lands of Maine where vast stores of wood could be felled next to tidewaters whose location was propitious for sawmills in close vicinity. The short haul of local timber was just one of many cost advantages conducing to a maritime industry of international repute. Economies were aplenty in the midst of the early years so long as it was not necessary to venture deep into the interior across marshes for the purpose of cutting down forest lest shipyards become crippled by the paucity of inputs. In the fourth quarter of the 18th century shipbuilding was then a staple for the seaboard economy as production intensified.

0 notes

Text

The Demand-Pull Economics of Space

To look out at this kind of creation and not believe in God is to me impossible.

John Glenn, 1962

Investment that seeded the space race opened a number of market opportunities for major firms amongst the cascade of downstream effects visited upon the private sector. In the main what government largesse basically did was stimulate the production of new technology for NASA whereupon each $1 billion earmarked from Federal spending added 20,000 employees to America’s payroll (Evans 1976). And yet far more pregnant with consequence than this dynamic of job creation is not this influx of labour so much as its nature. Rather than run-of-the-mill openings like in hospitality or retail what proliferated instead was employment defined by a great intensity of STEM research. What this disruption to the status quo intimates is the reality of how breakthroughs in science go on to parent new technologies whose later use enables an economy to produce more than what it did previously. A distinction then differentiates conventional versus high-tech employment. In the parlance of economists the former maintains the existing Production Possibility Frontier whilst the latter pushes its boundaries outward. The concept of PPF adverts to the maximum output an economy can produce within the parameters of its current technology. A great deal of innovation and productivity thus followed courtesy of public investment in NASA.

The magic of industrial policy here cannot be overstated. Creating jobs in industries informed by a high degree of human capital conduces to an economy becoming a hotbed for innovation. Borne out of this relationship are technologies that migrate into a sundry of other sectors which in turn ply them to increase their proper productivity and reduce costs. Observe the journey of microchips from Apollo’s Guidance Computer to robotic manufacturing. A serious revolution on production lines accompanied this technology as labour costs diminished commensurately with higher output whose economies were passed onto consumers by way of lower prices. Elsewhere the ubiquity of these semiconductors saw the exponential growth of computing power when efficiency gains were had from processing data. Whether it be point-of-sale systems like cash registers or the advent of ATMs in the financial industry or perhaps the cordless tools so common on construction sites NASA was a boon to America’s productivity. With greater production and its faster cadence which in the foregoing examples would imply more shopping or banking transactions or homes being built came a better standard of living since profits translate into wage growth. Ergo the knock-on effects in the economy were many.