Text

/k/ Planes Episode 103: German Night Fighters

It’s time for another episode of /k/ Planes! This time, we’re looking at the night fighters of the Luftwaffe.

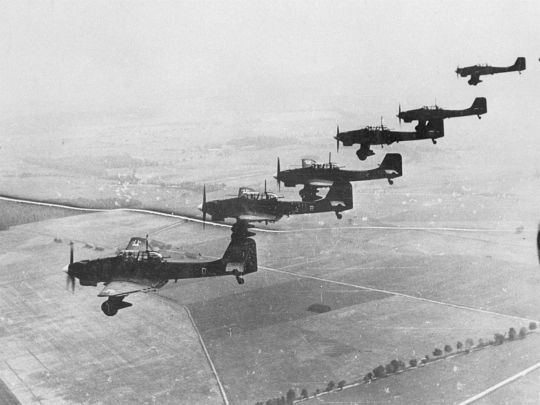

Early in the Second World War, the RAF made the decision to undertake a nighttime strategic bombing campaign. In doing so, they spurred the development of an elaborate air defense network in Germany centered around the use of night fighters. As the system evolved and expanded, an arms race began between the Luftwaffe and RAF, resulting in quite possibly the most technologically advanced theater of the entire war. Unfortunately, the night fighters had more than just the RAF working against them. From the start, they experienced resistance from high command, who perceived such an elaborate defensive network as defeatist. Offensive arms of the Luftwaffe were consistently given priority over the night fighter corps, and, even when resources were allocated, the night fighter corps was often left competing with cities to improve their network. Even so, Germany’s nighttime air defense network would come to be one of the most elaborate and effective defensive networks of the entire war, only truly losing its effectiveness after factors beyond the control of the night fighter corps began to degrade their network.

Background

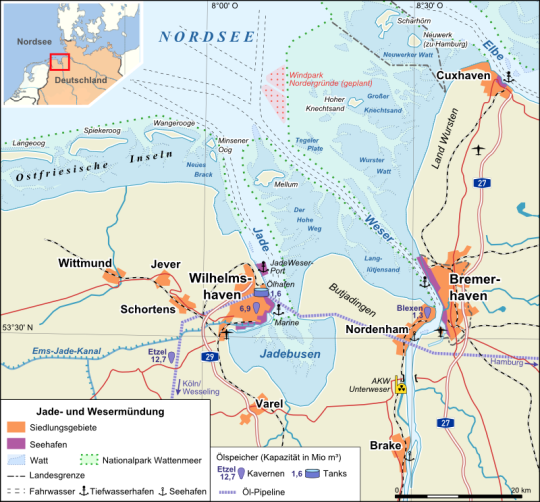

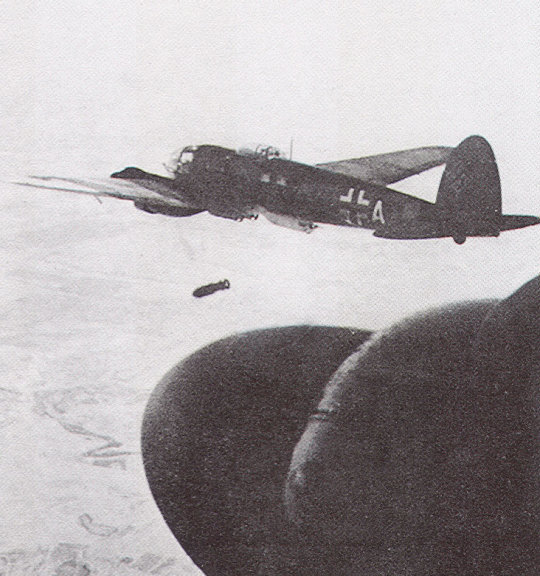

In the opening months of the Second World War, Britain had begun limited bombing efforts against Germany. Though the RAF had in its possession a sizeable force of long-range bombers, they lacked any fighters capable of escorting them. Night bombing had been a regular practice of the RAF in the years leading up to the war, but most raids would be conducted in daylight without fighter escort. Such missions went predictably poorly. Despite their comparatively heavy defensive armament, British bombers were far too vulnerable to German fighters. This vulnerability was demonstrated in its extreme in December 1939, when the RAF sortied 22 Vickers Wellington bombers to attack the Kriegsmarine base at Wilhelmshaven. The bombers were picked up by German radars an hour out from their targets, and, though they arrived over the target without being intercepted, they were followed much of the way home by a massive force of German fighters. Without escort, the bombers suffered the loss of 12 aircraft, along with a further 3 damaged. Though the RAF had suffered heavy losses before, this most recent engagement over Heligoland Bight was the final straw. Daylight operations were to be completely abandoned.

Freya Radar

In early 1933, after promising tests of Sonar systems, the Kriegsmarine began experimenting with radar systems. Rudimentary systems were developed at first for a proof-of-concept, but, after successfully showing that a radar system could detect surface ships several miles away, the project gained significant support from the Kriegsmarine. While the Kriegsmarine went on to develop surface-search radars for their ships, the concept saw surprisingly little interest among the Luftwaffe. Though the Kriegsmarine’s radar experiments were showing the clear ability to detect aircraft at range as well, such a system was looked down upon for numerous reasons. First and foremost was an institutional bias against an early-warning network, as it was felt that such systems were purely defensive in nature and thus useless for Germany’s offensive focus. The Luftwaffe had its practical reasons to not want the systems, however, as they lacked a real command and control network that would be necessary to make the most of such systems.

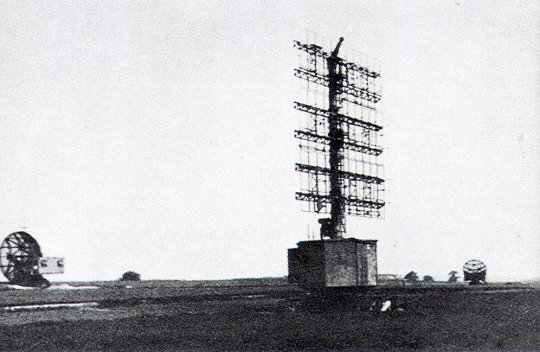

Because of the resistance to air-search radars, it wouldn’t be until the eve of war that the first radar stations were deployed. In early 1937, after successfully delivering their first operational radar sets to the Kriegsmarine, the company GEMA began work on an air-search radar. Known as Freya, the new system was derived from the Seetakt radar developed for the Kriegsmarine, differing in its lower frequency range (120-166MHz vs 368MHz), longer wavelength (2.5m vs 50cm), and longer range (120km vs 20km). The Freya system was ordered by the Luftwaffe in 1938, with the first eight systems reaching service that year. Compared to the Chain Home system being used across the Channel, the Freya was considerably more advanced. With its smaller wavelength, it could use a smaller and more manageable antenna and provide higher resolution images for operators. However, this came at the cost of complexity - only eight Freya stations were operational when war broke out.

Though the Freya network had large gaps in its coverage early in the war, it would come to demonstrate its utility very quickly. When the RAF made their raid on Wilhelmshaven on December 18, 1939, they were picked up by two Freya radar stations at a range of 113km. Poor coordination prevented the Luftwaffe from intercepting the bombers before they made landfall, but Freya operators were able to guide intercepting fighters to the formation, leading to such devastating losses that the RAF would abandon daylight raids altogether. This success prompted a massive expansion of the radar network. Three more Freya nodes were operational by early 1940, and, once France fell, Freya installations began to pop up all along the occupied Atlantic coast.

Wurzburg

GEMA would follow up on the Freya radar with a more precise piece for guiding AAA and searchlights. First demonstrated in mid-1939, the new set - known as Wurzburg - was an ultra-high frequency radar with a range of 553-566MHz. With a wavelength of a little over 50cm, the Wurzburg could provide much more precise information, so much so that searchlights could be directed with reasonable accuracy towards individual aircraft. As originally conceived, the Wurzburg consisted of a 3-meter dish antenna on a manually operated rotating mount. Tracking targets was done by scanning for a maximum return on the oscilloscope display. In this arrangement, the Wurzburg was hardly a very practical device. Tracking targets was difficult, and, with a range of under 30km, the system was reliant on other elements of the early warning network to alert them of incoming aircraft.

The first Wurzburg sets made it into service in 1940, and very quickly they began to prove their worth. In May 1940, Wurzburg sets were credited with their first shoot-downs, with crews tracking targets and verbally relaying the commands to nearby flak and searchlight units to engage aircraft. As the Kammhuber Line took shape, the Wurzburg set became an integral part of German night-fighting operations. Freya radars would detect incoming aircraft at a standoff range, relaying a general area for the Wurzburgs to scan. Wurzburgs within range would then search for the aircraft, directing nearby flak and searchlights, and even the occasional fighter, to the incoming aircraft.

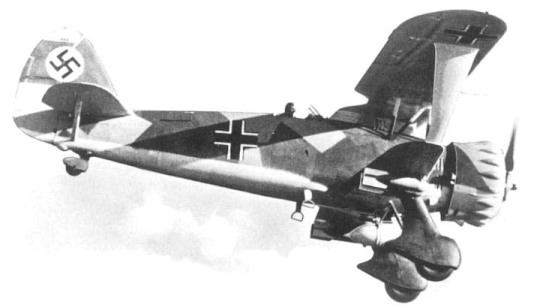

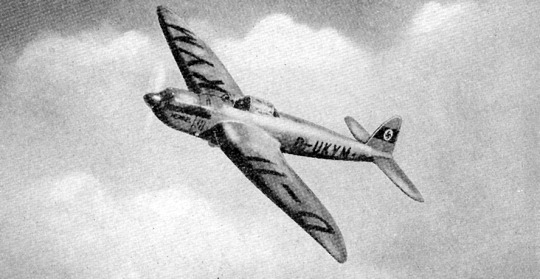

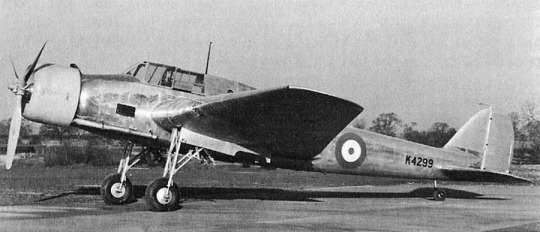

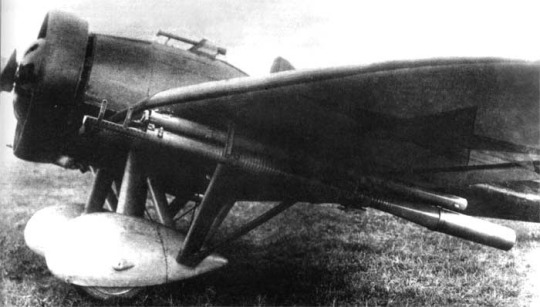

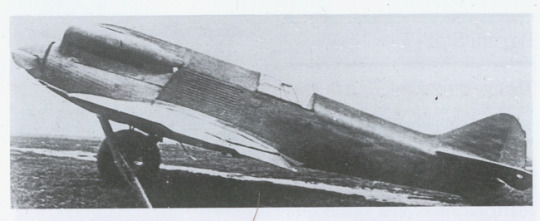

Night Fighters: Messerschmitt Bf 109

The first fighter the Luftwaffe would commit to night fighting duties was the ubiquitous Bf 109. With no dedicated night fighters in the inventory at the outbreak of war, the Bf 109 was pressed into the role. The Bf 109 was hardly an ideal platform for the role, being a short-ranged single-man machine with no special equipment for night fighting. However, with an onboard radio, the Bf 109 could be directed by ground stations to incoming aircraft. By 1940, the practice of night fighting with the Bf 109 had been fairly well ironed out. Freya radars would detect inbound enemy bombers, and a general intercept area would be relayed to sortieing Bf 109s. Searchlights would then attempt to illuminate the target aircraft, allowing the fighters to acquire the targets visually to engage. With the arrival of the Wurzburg sets later that year, the effectiveness of such missions increased. However, the Bf 109 remained far from an ideal platform, and, with the limited resources available for the defense of the Reich, the practice was unable to prevent RAF bombers from getting through. For the time being, the Bf 109 could manage, as poor navigational practices were making RAF raids incredibly ineffective. However, the RAF was rapidly improving, so something better than the Bf 109 was needed.

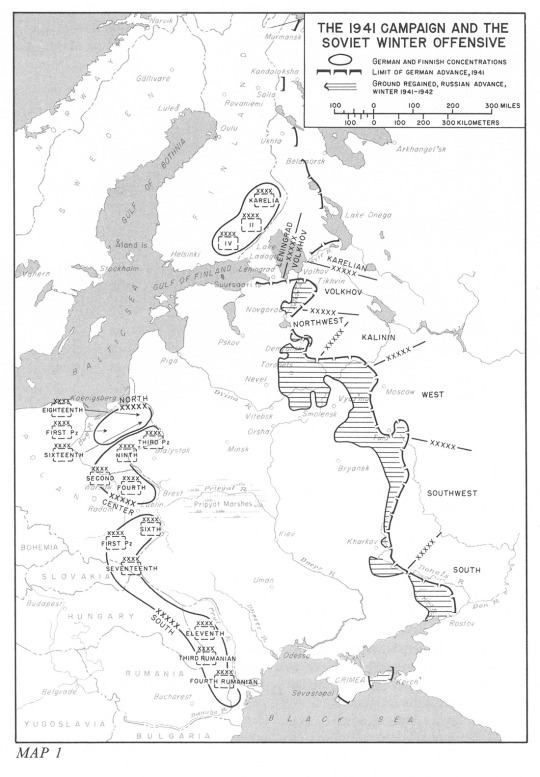

Kammhuber Line

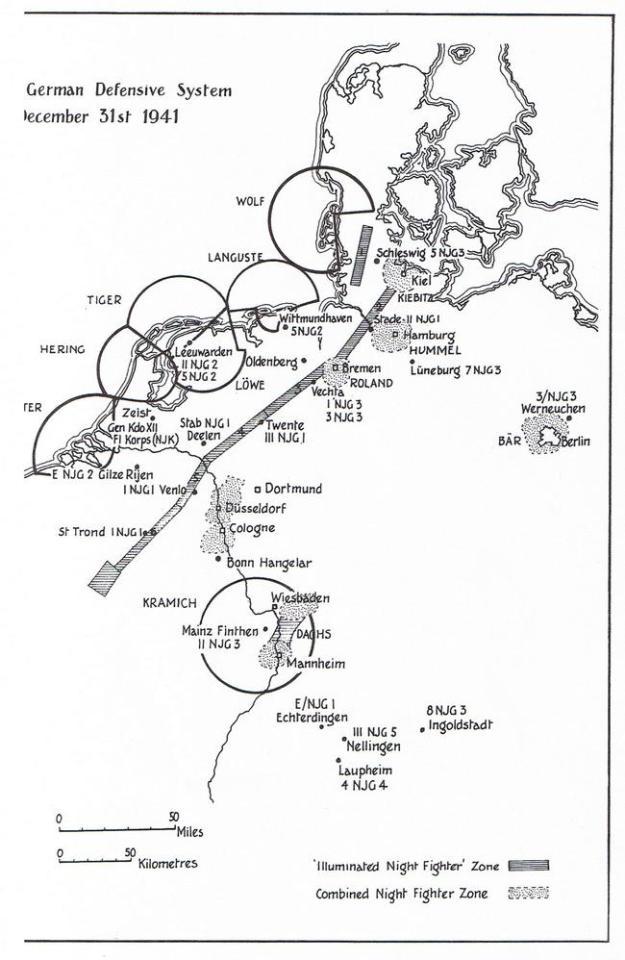

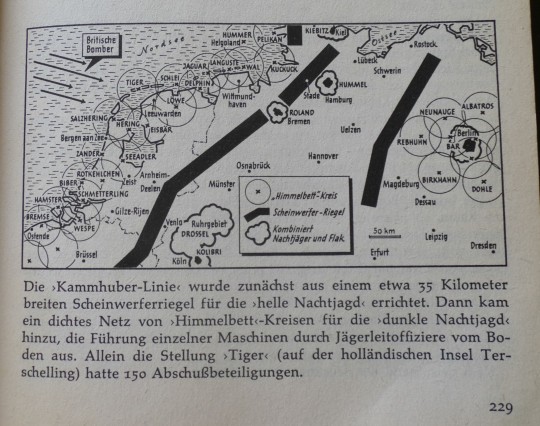

As France began to fold under the weight of the German offensive, the Luftwaffe took the opportunity to expand its early warning network. Starting in June 1940, the Freya radar network was expanded into occupied Europe, with stations growing to cover the the mouth of the Rhine to the Denmarks Straits. Meanwhile, in July 1940, Generalmajor Josef Kammhuber was placed in charge of the Reich’s flak, searchlights, and radars. When Kammhuber arrived, the system was in great disarray. Though local cooperation existed between stations and flak batteries, there was no single chain of command. The lack of communication was so poor that newly-developed operational practices were not being shared between stations, causing effectiveness of the air defenses to vary massively by region. Kammhuber swiftly addressed this. A new, streamlined command system was put in place, coordinating communication between radars, flak batteries, and night fighters. Construction continued until March 1941. As the Allies came to recognize the new network of defenses, they would dub it the Kammhuber Line.

The Kammhuber Line consisted of a well-organized network with three successive zones extending east from the North Sea. The first line was broken into “boxes” roughly 20 by 20 miles in size centered on control centers. Each box was assigned a single Freya radar system and two Wurzburg radars - one to track the bombers for searchlights, and the other to guide night fighters. Manually guided searchlights and flak batteries were also spread throughout the boxes, and a two night fighters - one primary and one backup - were assigned to the box. The three radar sets reported directly to their local control center, which used the data from the three sets to plot the movement of the incoming bombers and keep track of friendly fighters. Behind this frontier line were the “Henaja” (helle Nacthjagdraume) sectors, which consisted of belts of searchlights roughly 22km deep with night fighters assigned to them. Unlike the first line of defenses, the second line was reliant on sound detection equipment to alert operators of an incoming raid. Once the bombers were detected, night fighters were sortied, orbiting local beacons and waiting for the incoming bombers to be illuminated by the searchlights. Like the first layer, however, sectors were limited to just a single night fighter at a time to reduce confusion.

Beyond this second line of defenses, a final zone was established to protect target areas more directly. These final zones were a mix of the previous two. Defended by both night fighters and flak, they were the last line of defense over German cities and industrial areas. Berlin was given an extra line of defenses as well, with a Henaja sector west and northwest of the city in addition to the mixed sector over the city itself. Kammhuber’s system would evolve over time. When construction began in 1940, the Wurzburg radar had yet to enter service, so ground operators were reliant on just the less-accurate Freya. As the Wurzburgs became available, however, they came to augment the line. Once the air defense sectors along the front of the line were filled out, Wurzburg sets began to move backwards, in particular augmenting and finally replacing the impractical listening posts that supported the Henaja zones.

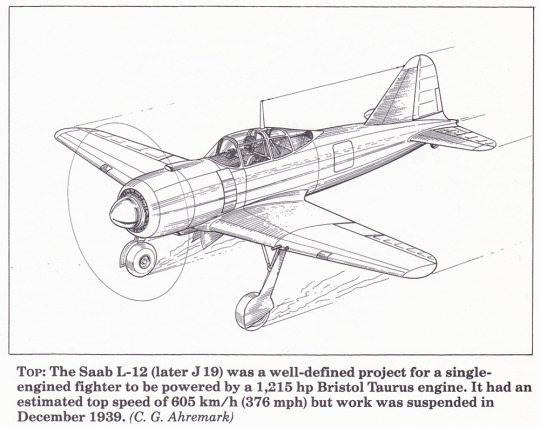

Though the Kammhuber Line was still under construction through the end of 1940, its effectiveness rapidly became apparent. In the second half of 1940, 170 RAF bombers were lost in raids on Germany. 72 were credited to Kammhuber’s night fighters, while 42 more were credited to regular Luftwaffe fighters and 30 to ground fire. With fewer than 60 aircraft operating across 16 Staffeln, the Kammhuber Line had inflicted a higher loss rate upon the RAF than the Luftwaffe had suffered in their own bombing campaign against Britain. And as the Line only continued to improve, RAF losses mounted. In 1941, 421 RAF bombers were lost to the Kammhuber Line. Unfortunately, things were not going entirely to Kammhuber’s plans. Kammhuber hoped to support the domestic defenses with an offensive campaign against the RAF’s bomber airfields. Though a modest campaign had been conducted through 1941, operations against the bombers never saw much priority, and, as the bombing of England ceased, the RAF received a much-needed relief that would only allow them to intensify their campaign.

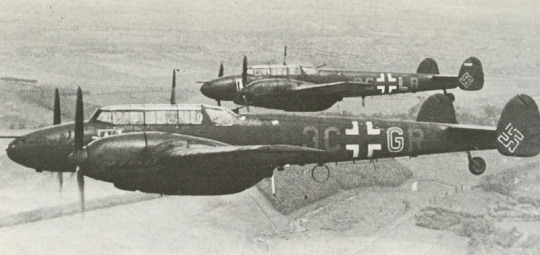

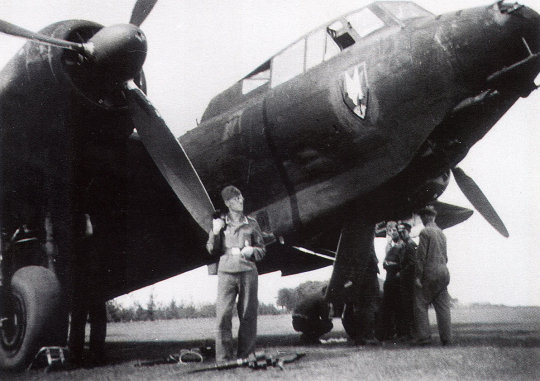

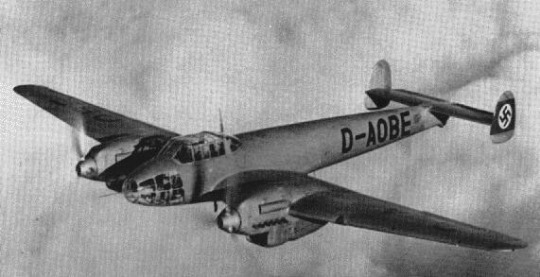

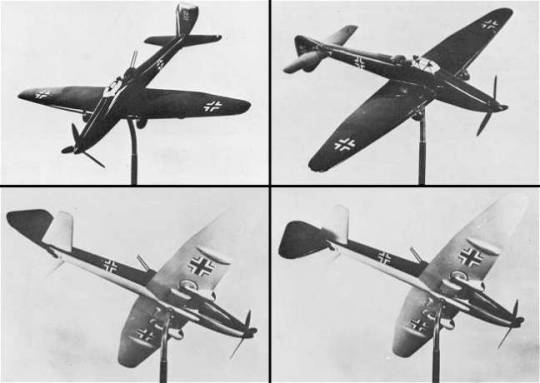

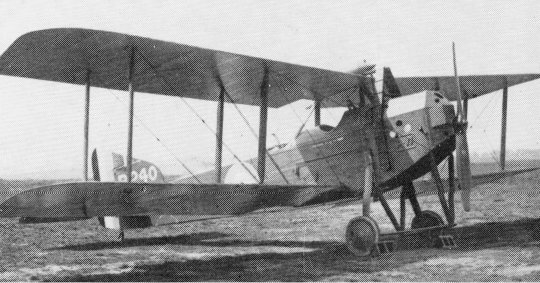

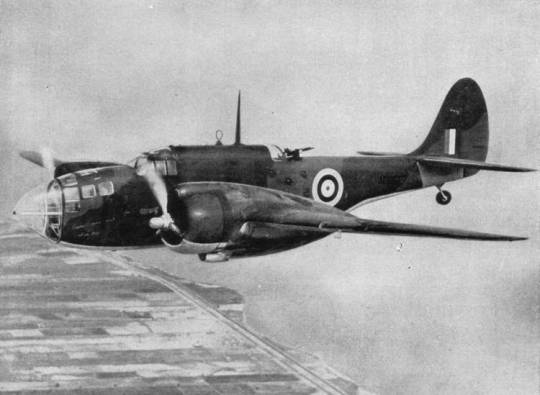

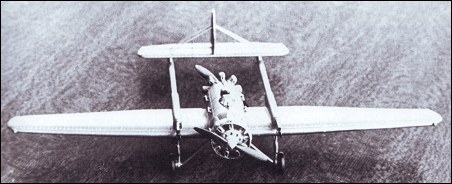

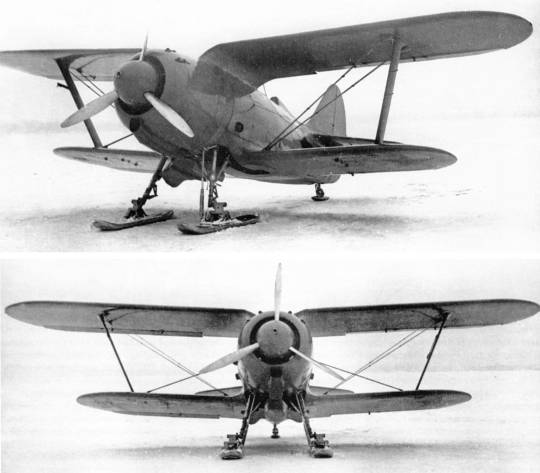

Night Fighters: Messerschmitt Bf 110

As the Bf 110 had proven itself to be incapable of holding its own as a frontline fighter, the fighter was gradually drawn back in the Fall of 1940. Small numbers of Bf 110s were passed onto Kammhuber’s night fighter forces, immediately proving its worth. Though the Bf 110 lacked the agility of the Bf 109, such shortcomings were of little consequence as a night fighter. However, the Bf 110 massively outperformed the Bf 109 in areas that mattered for night fighting - endurance, firepower, and extra carrying capacity. Early operations were not unlike those of the Bf 109 - unmodified fighters being directed by ground control to targets. Though the system was far from ideal, the low rate of bomber attacks and limited damage being done meant that the Bf 110 was more than good enough to get the job done.

Because of the limited effectiveness of the ground-based radar system, the Bf 110 would find itself at the forefront of efforts to make interceptions easier. By 1941, the new Bf 110E series was entering production, with two dedicated night fighter variants developed. The first made use of the spacious airframe to mount a passive infrared device - Spanner Anlage - to detect exhaust flares from British bombers. Its success was limited, as the British quickly modified their bombers to muffle the engine flare. The more successful variant was a simpler conversion, merely adding a third crewman to give the fighter an extra set of eyes. By mid-1941, however, these were being superseded by the Bf 110F-4 - the first purpose-built Bf 110 night fighter. The F-4 was designed around two new systems - the Lichtenstein air-intercept radar and the Schrage Musik upward-firing cannons. Though these too would be replaced by a newer variant, they marked a major leap in the Bf 110’s night-fighting abilities.

The ultimate development of the Bf 110 night fighter would be the Bf 110G-4. Designed from the start to mount an air intercept radar, the G-4 would see constant updates to its electronics suite to keep it relevant. By the time the Bf 110G-4 began entering service in mid-1943, it was now seen as one of the less capable night fighters, owing to its lower endurance and limited firepower. A series of field modification kits would arise, doing everything from augmenting firepower (either with Schrage Musik guns or replacing the 20mm cannon with 30mm Mk 108s) to expanding fuel capacity. Despite shortcomings, the Bf 110G-4 would be the mainstay of the Luftwaffe’s night fighter corps. Production was handed off to Gotha, with over 1,800 built before production finally ended in February 1945.

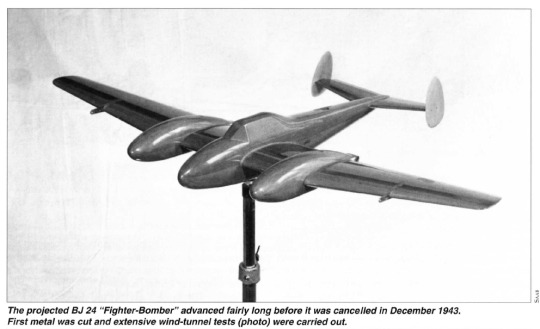

With the introduction of the dedicated night-fighter Bf 110 variants, RAF losses spiked. Even as the RAF began introducing tactics like the Bomber Stream to overwhelm defenses, the Bf 110 exacted a heavy toll on the bombers. The introduction of such systems like the airborne radars and Schrage Musik armament would massively improve the Bf 110’s effectiveness, and, in 1943, Bf 110s would play a part in the destruction of 2,751 RAF bombers. Unfortunately, this excellent performance would not last forever. The introduction of countermeasures such as Window and feint attacks with de Havilland Mosquitos confused defenses and often led to the (comparatively) short-ranged Bf 110s straying too far from the real targets to make interceptions. Worse, Goering was forcing Kammhuber to commit the night fighter force to combatting the daylight raids as well, leading to heavy attrition.

Though losses would subside after the heavy fighters were finally withdrawn from daylight operations, the Bf 110 would get little respite. The development of radar warning receivers by the RAF allowed for the bombers to start being accompanied by escort night fighters. Weighed down by the heavy night fighting equipment and unable to distinguish on their radars between RAF bombers and their accompanying night fighters, the Bf 110s would begin to suffer increasing losses on night missions as well. Losses only continued to worsen as the war went on, and, as the Kammhuber Line fell apart in late 1944, the Bf 110 was no longer capable of operating effectively. The Bf 110 continued flying as a night fighter to the end of the war, but production would halt in February 1945 to free up resources for more promising endeavors.

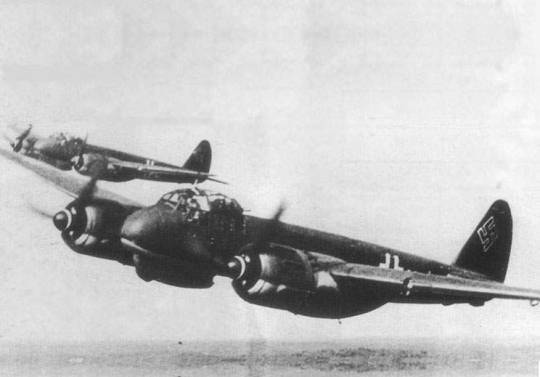

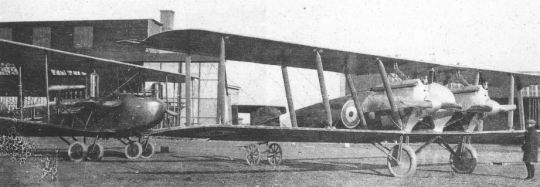

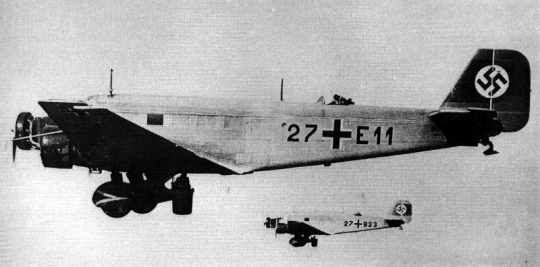

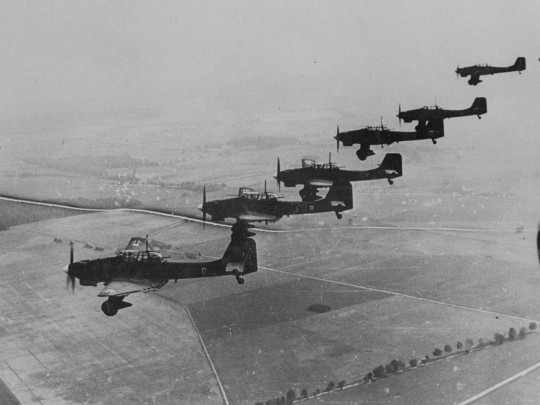

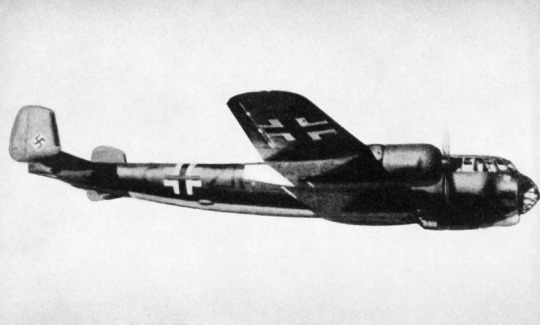

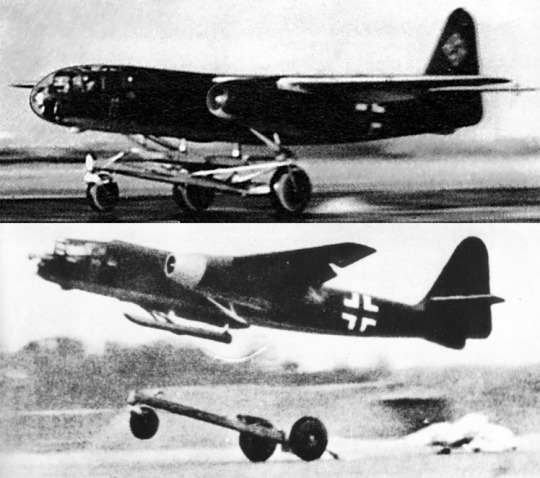

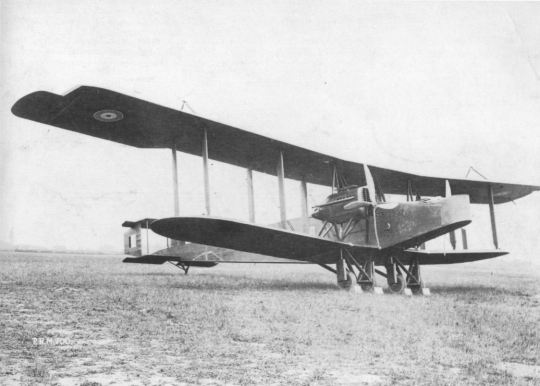

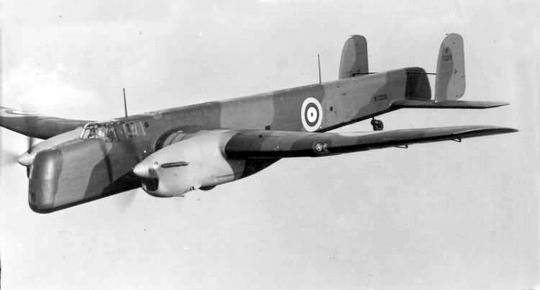

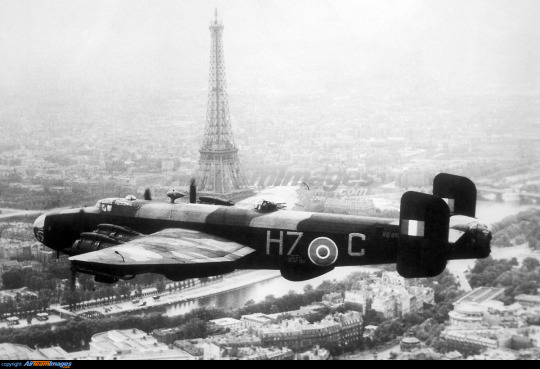

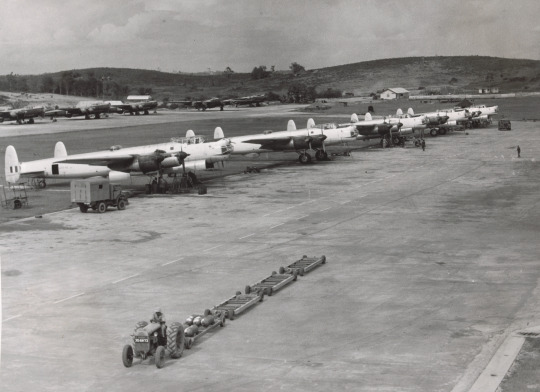

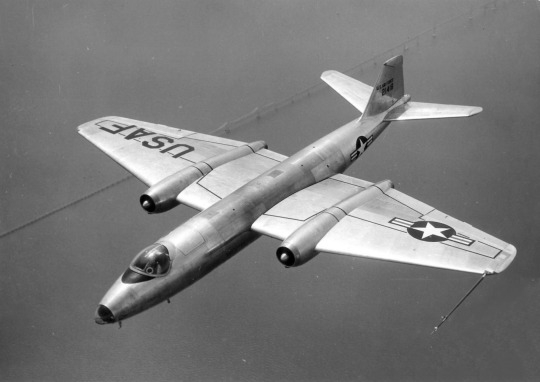

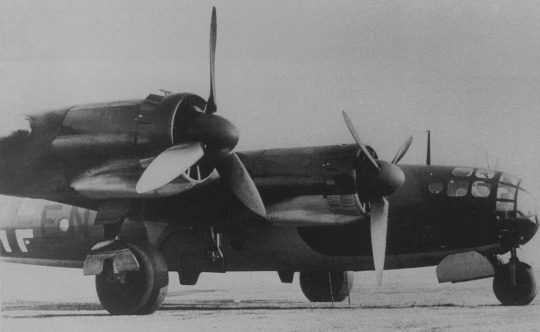

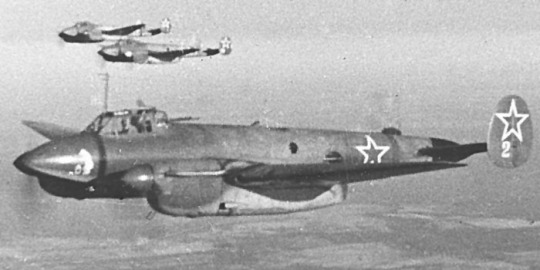

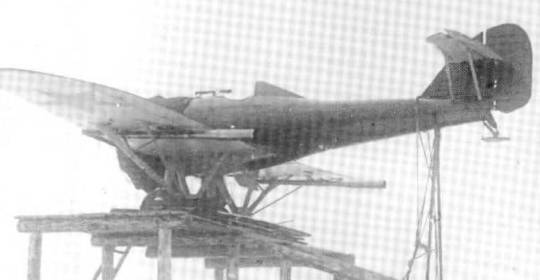

Night Fighters: Junkers Ju 88

As the Kammhuber Line took shape, small numbers of Ju 88Cs were committed to serve as night fighters. The Ju 88C was originally developed as a heavy fighter, with three MG 17s and a single 20mm MG FF installed in a new solid nose. At first flying with a Zerstorerstaffel of KG 30, they were broken off in July 1940, forming II./NJG 1. Unfortunately, lackluster performance in the early months of the war meant that production of the Ju 88C was limited, even after it took on the night fighter role. After becoming I./NJG 2 in September 1940, the sole Ju 88C unit took a more aggressive stance in the defense of the Reich. Unlike the Bf 110s, which were mostly kept in the rigidly structured network Kammhuber had developed, the Ju 88C was flown on night intruder missions over Britain. These missions coordinated with intercepted RAF radio transmissions and projections from friendly radars, with Ju 88s sortied to intercept the RAF bombers over England as they returned to their airfields. The Ju 88s would orbit the bomber airfields, picking off the aircraft as they presented themselves. Alternatively, payloads of bombs would be dropped across runways.

Operations continued for a year with excellent results. Though they started with just 7 aircraft on hand, the unit claimed 143 RAF bombers. Unfortunately, attrition of the fleet and the lack of any tangible results would lead to Luftwaffe commanders halting the attacks on Britain in 1941. With the night intruder mission over Britain over, I./NJG 2 was shifted south the the Mediterranean in October 1941. IV. and II./NJG 2 followed soon after with deployments to Sicily and Benghazi, respectively. Their first kills came in December, when a Ju 88C downed a Beaufighter over Crete, and several days later, a Hurricane was claimed as the fighters escorted Ju 88s making attacks on Malta. Through 1942, Ju 88Cs were spread across the Mediterranean to meet night fighter needs. Despite lacking a coherent air defense network like the Luftwaffe enjoyed over Northern Europe, the Ju 88Cs performed reasonably well. In October 1942, Leutnant Heinz Struning of IV. /NJG 2 was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross for downing 24 enemy aircraft.

The Ju 88 returned to Germany as a night fighter in early 1942, when the first Ju 88Cs equipped with the new Lichtenstein air-intercept radars entered service with I./NJG 1. Flying their operational trials with the unit, they performed well enough to be ordered into production in the new configuration. Delays in production slowed the type’s entry into service, but by the start of 1943, the radar-equipped Ju 88Cs and newly developed Ju 88R (mounting the BMW 801 engine along with radars) had reached squadron service in significant numbers. Unfortunately, just as operations kicked off, disaster struck. A Ju 88R, complete with a full crew and all its advanced electronics, defected to Britain in May 1943. The capture of an intact Lichtenstein radar system allowed the RAF to refine their tactics and countermeasures, leading to the development of the Window chaff system that began to appear in the skies over Europe in July 1943.

As the new countermeasures compromised the Kammhuber Line, the Ju 88s were forced to adapt. Newly developed tactics called for night fighters to be sortied once a raid was determined to be coming, with the fighters orbiting beacons until the bomber stream was identified. Such tactics put an emphasis on high endurance - something the Ju 88 had over all the other night fighters. With this newfound superiority, production of the Ju 88 night fighter variants accelerated. These new tactics, coupled with the arrival of the newest radar systems, mitigated the impact of the British countermeasures and led to mounting losses. By the end of 1943, losses among the RAF bomber forces were getting unsustainably high.

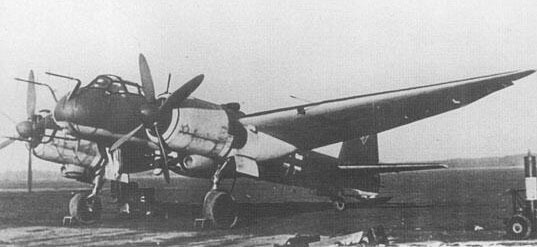

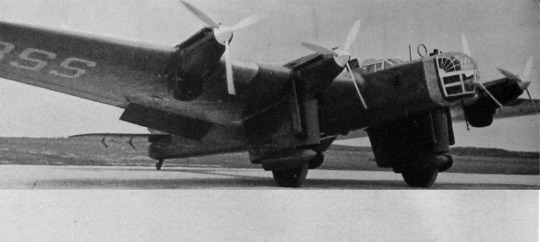

In late 1943, the ultimate night fighter variant of the Ju 88 entered production. Designated Ju 88G, the new variant was a major overhaul of the design. An all-new fuselage was built for the Ju 88G, omitting the Bola ventral gondola and introducing the enlarged tail of the Ju 188. Powered by the BMW 801 radial engine, the Ju 88G was fitted with the newest electronic equipment - the FuG 220 Lichtenstein radar in the nose and FuG 350 Naxos or FuG 227 Flensburg radar detector in fairings around the aircraft. Four 20mm cannon were carried in a ventral pack, while provisions for two more in a Schrage Musik upward-firing mount were also added. Fuel tanks were also expanded to increase the fighter’s endurance.

Though the Ju 88G marked a new level of effectiveness among the night fighters, it too would soon be the center of disaster when a Ju 88G-1 mistakenly landed in Essex after an issue with the onboard compass. The newly developed radars were captured, and the RAF developed a modified version of their Window countermeasures that once again left the night fighters blinded. By the time new radar sets were available to regain the advantage, the worsening situation on the ground was becoming more critical. The Kammhuber Line began to fall apart at the end of 1944, meaning the early warning radar network could no longer be relied on. Worse, fuel shortages were now hitting the night fighter fleet, negating the Ju 88’s endurance advantage. The final blow came at the end of the war, when the Luftwaffe threw its night fighters back into daylight combat, with predictable results. Already having suffered heavily in 1943 when used against daylight raids in friendly air superiority, the Ju 88 night fighters couldn’t hope to compete in the face of Allied air supremacy. After suffering catastrophic losses, the fleet was finally grounded in early April 1945 owing to fuel shortages.

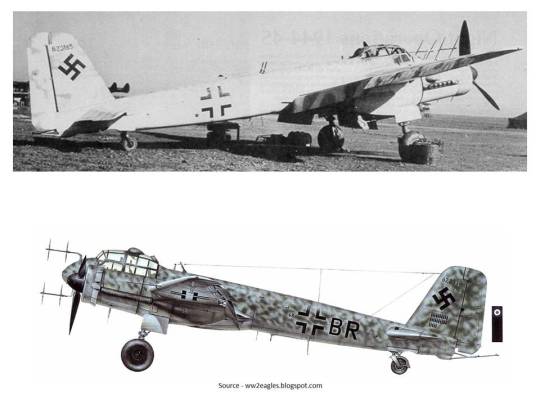

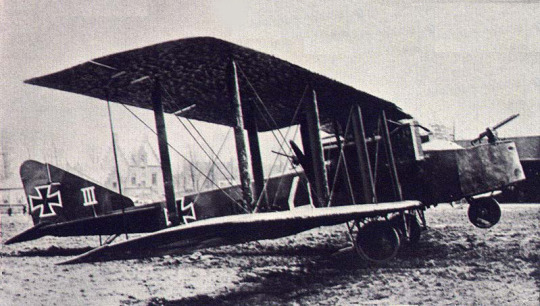

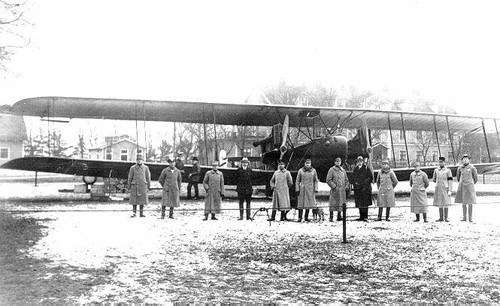

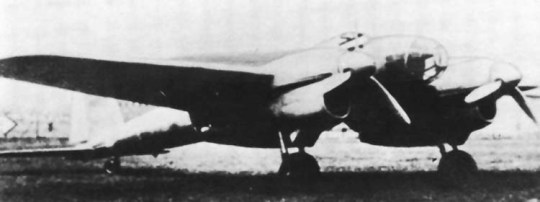

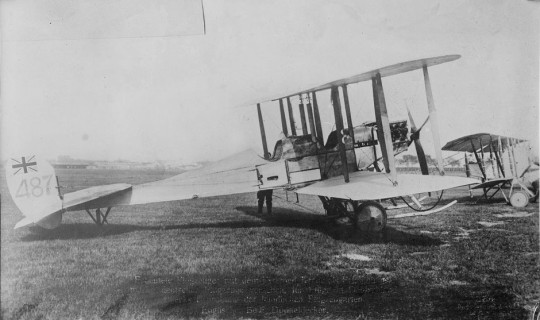

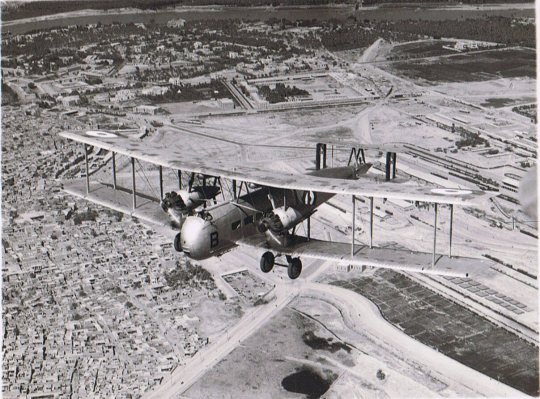

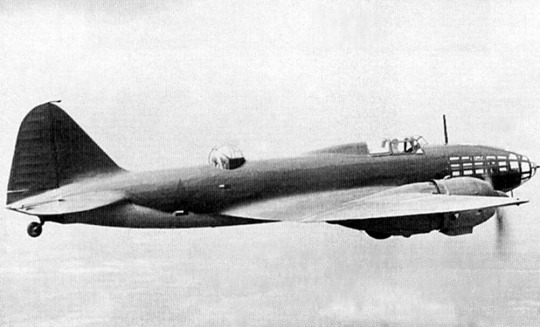

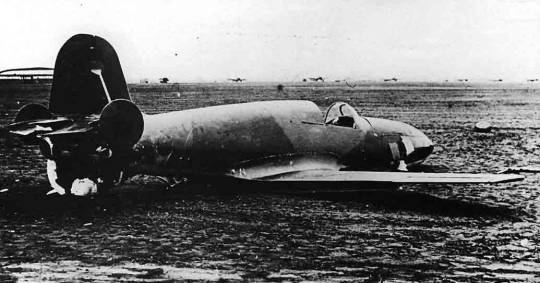

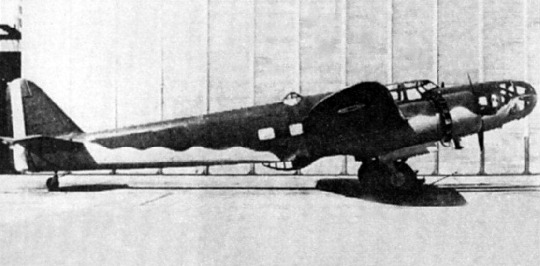

Dornier Do 17

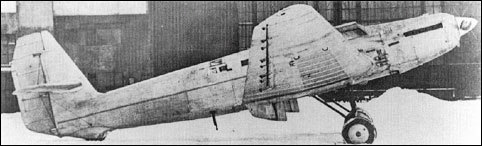

When production of the bomber Do 17Z variants ended in 1940, Dornier began experimenting with night fighter variants. Three Do 17Zs were fitted with the solid nose from the Ju 88C, turning it into the Do 17Z-7. Armed with three machineguns and a 20mm cannon, the Do 17Z-7 had a large fuel tank installed in the bomb bay and an armored plate placed in front of the crew compartment to protect the crew from defensive fire from the bombers. A more substantial reworking in the form of the Do 17Z-10 followed, with armament revised to four machineguns and two 20mm cannon and a Spanner-Anlage infrared detection system installed. However, conversions were limited - only about 10 Do 17s were converted to the new standard. Entering service in 1940, they saw limited use. Crews found the Do 17 to be inferior to the Ju 88 night fighters, and, though experiments were done with mounting the Lichtenstein radars on the Do 17s, the fleet was never fully converted, and surviving aircraft were withdrawn from frontline service in the summer of 1942. Despite a generally poor service record, the type did see use by some of the night fighter Experten, particularly Helmut Woltersdorf.

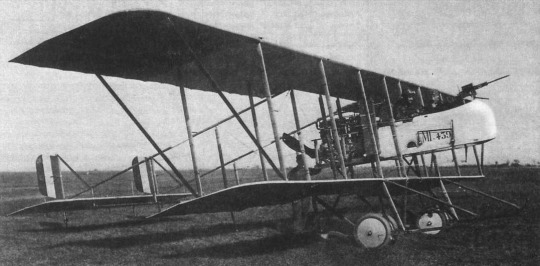

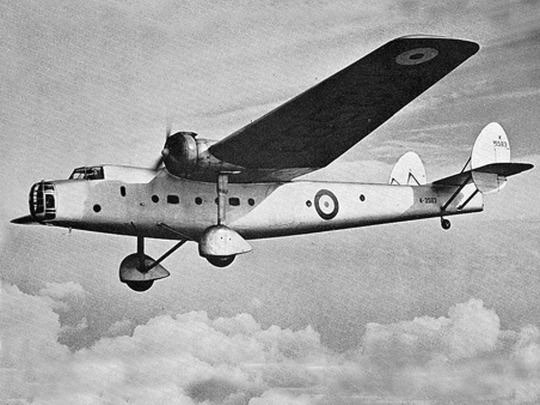

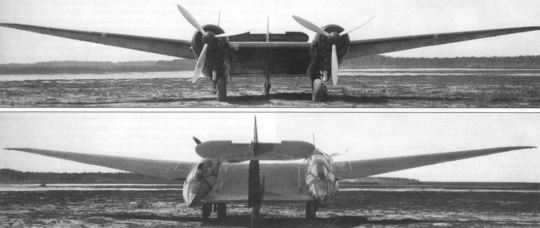

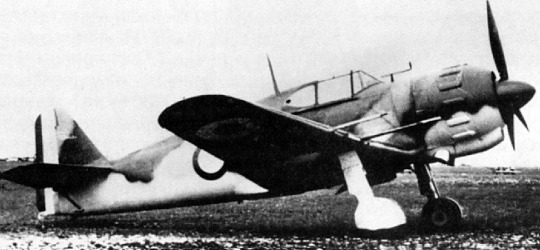

Dornier Do 215B-5

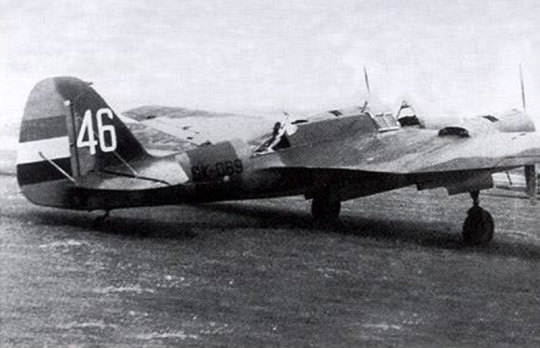

Dornier would also convert a number of Do 215s to night fighters. Taking 20 B-1 and B-4 variants, Dornier modified the aircraft along the same lines as the Do 17Z-10 conversion, with four machineguns, two cannons, and a Spanner-Anlage IR system in the nose. It followed the Do 17Z-10 into service, flying with elements of NJG 1 and 2. The IR detector in the nose rapidly proved to be useless, so, as the Luftwaffe experimented with the new Lichtenstein radar, the Do 215B-5 would be among the first aircraft to be upgraded with the new system. Unlike the Do 17Z-10, the whole fleet of Do 215B-5s would be converted to carry the Lichtenstein radar in 1942. Even with these conversions, however, the Do 215B -5 wouldn’t last much longer than the Do 17 night fighters - the Do 215 doesn’t appear to have lasted in the night fighter role into 1943.

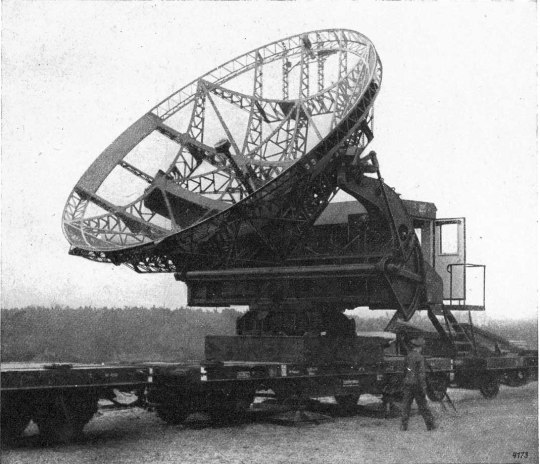

Wurzburg-Riese

In 1941, GEMA followed up on their successful Wurzburg system with a larger, more sophisticated set fittingly known as Wurzburg-Riese (giant). Making use of the same conical-scanning system developed for the “regular” Wurzburg sets, the Wurzburg-Riese was a much larger system with a 7.4 meter antenna and much more powerful transmitter that gave it a range of up to 70 degrees. Combined with the added accuracy afforded by the conical scanning system, the Wurzburg-Riese provided the Luftwaffe with a long-range system capable of providing accurate enough information for gun-laying. Because of the dish’s larger size, the Wurzburg Riese was placed on a powered mount, complete with an enclosed cabin for the crew to work in. The Wurzburg-Riese began to enter service in 1941, and over the course of the war roughly 1,500 would be built. However, it appears the Wurzburg-Riese never fully replaced the smaller Wurzburg sets. Rather, production and use continued alongside the regular Wurzburg until the end of the war. Though only the Wurzburg-Riese was accurate enough for gunlaying, the conical scanning system was still accurate enough for the regular Wurzburg to direct night fighters and searchlights, all while being significantly less resource-intensive to produce and operate.

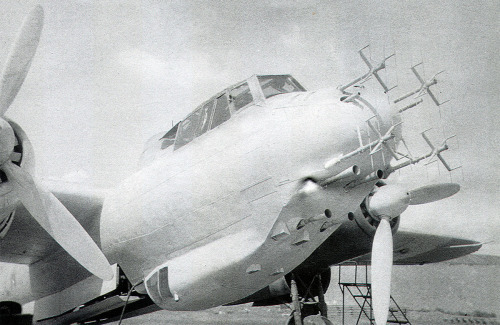

Lichtenstein

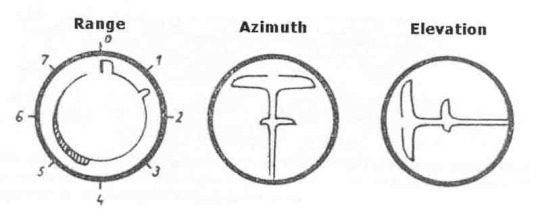

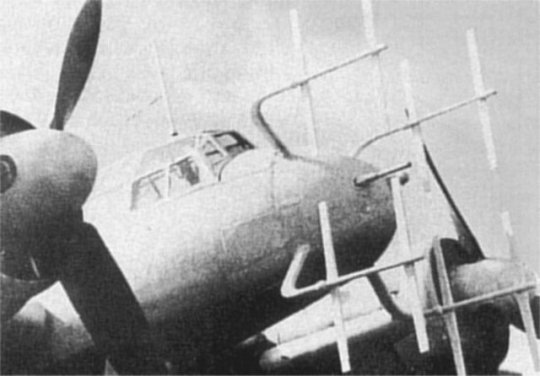

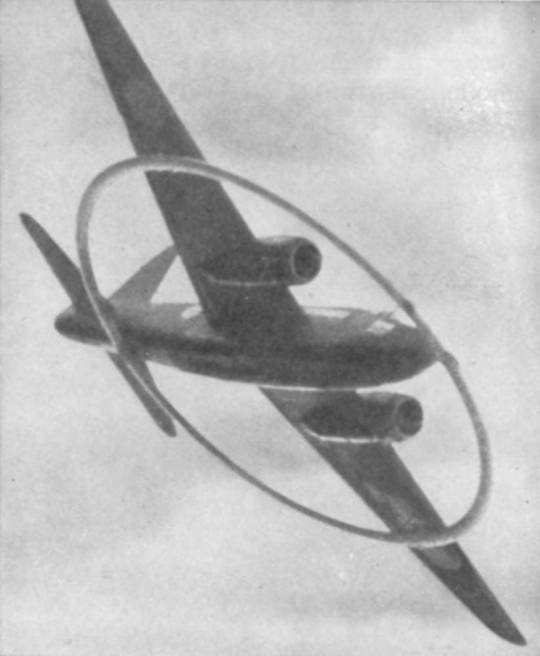

Though a sophisticated ground-based radar network would be established by early 1941, there was still a glaring need for an aircraft-based system for the night fighters. The first such system would take shape in mid-1941, a product of the Telefunken company known as Lichtenstein. The Lichtenstein radar sets consisted of four cross-shaped antennas mounted in the nose of an aircraft. Operating at 600 MHz, the system had a fairly short range - maxing out at just 4 kilometers and having a minimum range of 200 meters - but, with the accuracy afforded by conical scanning and the aid of ground-based systems would mean that the fairly limited capabilities of the system were still a major leap. Limited operational trials were conducted in 1941, but it took until 1942 for the Lichtenstein radar to get into service as Telefunken refined the system.

The first Lichtenstein B/C FuG 202 sets entered operational service in early 1942 aboard Ju 88s and Bf 110s. Intercepts with the new system continued with the same practices that Kammhuber had developed. Freya radars would detect the incoming bombers at a distance, directing the Wurzburg sets as the targets got closer, which would then in turn direct the night fighters as they closed in. The FuG 202 would be used in this critical final stage of the intercept, allowing the onboard radar operator to direct the pilot to the target rather than relying on a less accurate ground-based set. The impact of the Lichtenstein was quickly apparent to the RAF. Losses rose, and operators listening in on German radio transmissions were regularly hearing references to an “Emil-Emil.” It wouldn’t be until late in 1942 that the RAF finally learned that it could be an air intercept radar. To confirm the suspicions and learn what kind of radar they were working against, the RAF sent out a lone Wellington bomber fitted with radar receivers to gather details about the frequency range of the new radars. The mission was a success - the Wellington was intercepted, and, though badly mauled, it made it home with data on the new system.

Though this data would prove useful for the RAF, they wouldn’t be able to develop a truly useful countermeasure until a Ju 88, complete with an intact FuG 202 and mostly cooperative crew, defected in May 1943. With a full working set now in their hands, the RAF was able to tailor a new countermeasure - chaff deployment codenamed “Window” - to the radars. By the time this was ready, however, the Lichtenstein B/C was already old news. The FuG 202 had been refined into the FuG 212 by dropping its frequency to extend range and provide a wider view angle, but this too was soon superseded by a far more advanced set. Designated FuG 220 and known as the Lichtenstein SN-2, the new set dropped to a far lower frequency - 81 MHz - that provided a much longer range, wider field of view, and, most critically, relative immunity from British jamming. Because the FuG 220 operated in the same range as the Freya, it took time for the British to recognize its presence. The FuG 220 required a larger antenna array in the nose, producing more drag, and, with a minimum range of 500 yards in early sets, it still lacked the ability to perform close-range targeting. To compensate, the old B/C sets would stick around for a bit, albeit in a greatly reduced form, as it was found that the drag from both the FuG 202 and 220 mounted simultaneously was unacceptable.

Because of the appearance of the Lichtenstein SN-2, the new British countermeasures were far less effective than the RAF had hoped. Though a combination of jamming and Window deployment, the Lichtenstein B/C was effectively blind for the latter half of 1943, but the RAF struggled to counter the SN-2. It wouldn’t be until July 1944, when a Ju 88G equipped with a FuG 220 radar mistakenly landed in Britain due to a navigational error, did the Allies finally develop countermeasures for the SN-2. Jamming was fine-tuned to the new sets, and the Serrate radar warning receiver was developed to allow for Mosquito heavy fighters to hunt down and destroy German night fighters by tracking their radar emissions.

With the Lichtenstein SN-2 compromised, the system’s days were numbered. As jamming closed off the bands in which the Lichtenstein operated, some units transitioned to other sets operating on different bands, while others reworked their antennas to optimize them for the still-operational bands. Attempts were made to refine the Lichtenstein into a new system that could work on a wider spectrum, but by then the war was reaching the point where it made little difference. The last development of the Lichtenstein - the FuG 228 SN-3 - was small enough to fit in a streamlined fairing in the nose of a Ju 88G, but it arrived so late in the war that it saw little service. Even if they had managed to see significant service, they would have been of little use as Germany’s air defense network dissolved.

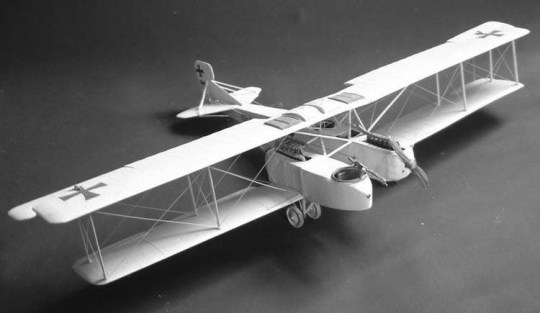

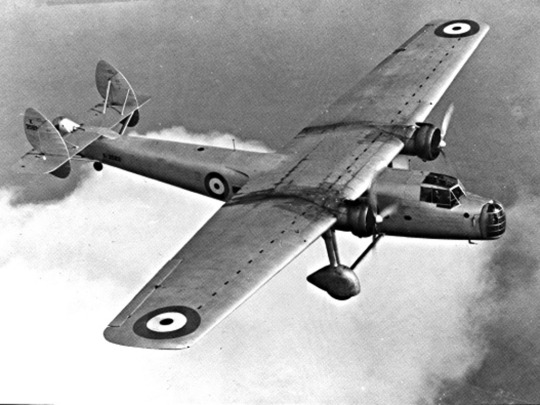

Dornier Do 217

Dornier’s next attempt to produce a night fighter would be a conversion of their Do 217 bomber. Owing to shortages of Bf 110s and Ju 88s, the decision was made to experiment with a night fighter variant of the Do 217E. Taking shape as the Do 217J, the aircraft was given a new solid nose with four forward machineguns supplemented by four 20mm cannon placed in the ventral gondola. The dorsal turret of the bomber was retained, as were the bomb bays, meaning the night fighter could still carry a payload of eight 50kg bombs. As the prototype, converted from an E-2, took shape in early 1942, it would also mount a FuG 202 radar and Spanner-Anlage infrared sight. Poor performance of the IR system lead to its omission on early series Do 217Js, and, owing to availability issues, the FuG 202 would not make it onto the first series of production, but overall, the prototype performed well enough for production to begin in March 1942.

The first Do 217J-1 reached 4./ NJG 1 soon after production began. Though it carried a formidable armament, it was not popular with crews. The Do 217J was found to be too heavy and unwieldy, with a poor climb rate and unsatisfactory takeoff and landing characteristics. Because of the decision to retain much of the bombing equipment, the Do 217J was significantly heavier than the Do 217E it was derived from. Nevertheless, production continued through 1942. Because the fighter retained its bomb bay, they picked up the night intruder mission that had been halted in 1941, intercepting and harassing RAF bombers as they returned home. However, this role was short-lived, and, as the Luftwaffe again abandoned night intruder missions, the order was given to halt Do 217J production. Dornier kept the production lines going, but by the end of 1942 only 130 Do 217J-1s had been built.

The J-1 was followed by the J-2, which aimed to address some of the shortcomings of the design. The Do 217J-2 installed the FuG 202 radar in the nose of the fighter and faired over the bomb bay, while the MG FF/M cannon were replaced with MG 151/20 cannons. Unfortunately, these changes did little to alleviate complaints, and in May 1942, Erhard Milch ordered Dornier to cease work on night fighters. Nevertheless, Dornier continued to refine the design, producing the Do 217N. The Do 217N addressed the sluggish performance of the J series with more powerful DB 603 engines, and, as trials of Do 217Js with the Schrage Musik armament were promising, the N-series was fitted with upward-firing guns. Fuel tanks would fill the faired-over bomb bay, though bomb release mechanisms remained, and a host of advanced navigational equipment - including the FuG 202 radar - was installed.

The Do 217N series entered service in January 1943. The N-1 proved just as disappointing as the earlier J-series, with its high endurance coming at the cost of poor performance, but, with the arrival of the N-2, Dornier finally had a workable night fighter. The N-2 finally removed the defensive armament and bomb release mechanisms from the design, dropping weight by two tonnes and allowing for major improvements in performance. Even with the changes, however, the Do 217N’s service was brief. The Luftwaffe began phasing out the type soon after it entered service, and it appears that none lasted beyond mid 1944. Despite consistently unfavorable reports, the Do 217 quite a bit of use by the night fighter corps. Over 300 Do 217 night fighters were built, and the aircraft flew with 11 Gruppen - though they never fully equipped any. Their high endurance gave them a niche advantage, making them particularly useful when deployed over Italy or the Eastern Front. When flying directly in defense of the Reich, however, they were generally found to be less capable than the other night fighters they served around, and, apart from a couple notable pilots like Rudolf Schoenert, crews tended to prefer other aircraft.

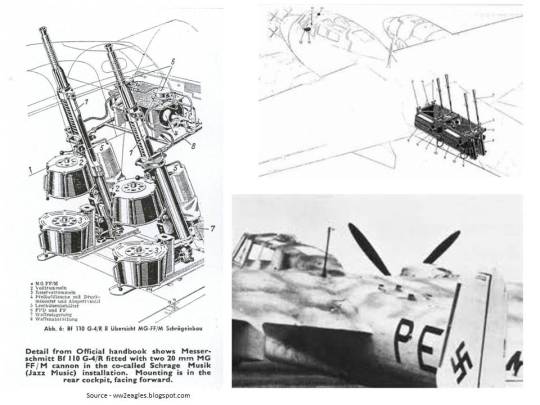

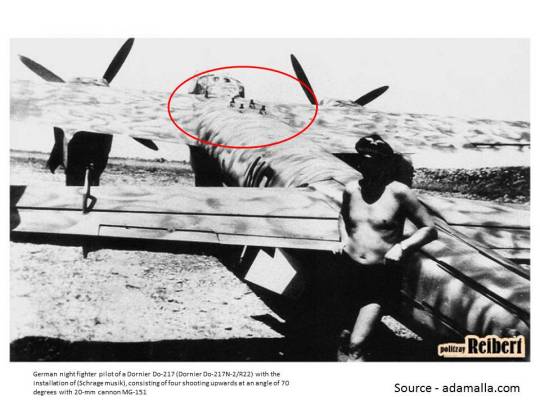

Schrage Musik

In 1941, Oberleutnant Rudolf Schoenert of IV. /NJG 2 began experimenting with a new armament layout on his Do 17. Rather than adding extra cannons firing forwards, he mounted two 20mm cannon behind the cockpit angled upwards. Though far from a conventional layout, it offered the benefit of allowing the night fighter to attack British bombers from below, where they lacked any defensive armament. Despite skepticism, Schoenert modified his Do 17Z-10 in late 1941 for operational trials. After several months of experimenting, Schoenert presented the idea to General Kammhuber, who authorized the conversion of three Do 217J-1s for further trials. Fitted with four to six upward-firing guns, the machines flew countless tests through the end of the year, allowing the Luftwaffe to refine the layout. Installed at an angle between 60 and 75 degrees, the arrangement would allow for the attacking aircraft to perform modest maneuvering while still keeping the target in its sights.

After trials showed the arrangement to be sound, Schoenert was put in charge of II./NJG 5, where he began modifying the Gruppe’s Bf 110s with the new gun arrangement, now known as Schrage Musik (Jazz Music). The conversion for the Bf 110 was fairly simple - a pair of MG FF/M 20mm cannon were mounted in the rear of the crew compartment, extending through holes cut in the top of the canopy. Schoenert himself took the system to the skies, claiming his first kill with it in May 1943. Meanwhile, conversion kits were developed for the Luftwaffe’s other night fighters as well. In June 1943, kits were produced for the Ju 88 and Do 217N, and, by August, enough fighters were equipped with the system for it to finally make its operational debut. Unsurprisingly, Schoenert himself became an expert with the system, claiming 18 kills from August 1943 to the end of the year using the Schrage Musik system.

The first operational use of the Schrage Musik system by pilots other than Schoerner came in August 1942 when the RAF bombed Peenemunde. Though diversionary tactics prevented the night fighters from intercepting the first two waves of the bombers, the third wave was caught by the Schrage Musik-equipped night fighters with devastating results - 40 bombers were lost. The success of the system prompted more conversions, and by 1944, a third of all night fighters mounted Schrage Musik guns. Even better, the arrangement was designed into the newest Ju 88 variant - the Ju 88G - and the new He 219. Overall, the Schrage Musik system was devastatingly effective. By the winter of 1943-44, Schrage Musik-equipped fighters were inflicting such a toll on RAF bombers that losses were no longer sustainable. Even better, because the profile kept the attacking aircraft out of view of the bomber’s gunners, Bomber Command was slow to recognize the threat, thinking that it was just unusually accurate flak.

Once the RAF did finally realize where the attacks were coming from, several changes were made. Some bombers were modified in the field with makeshift ventral gun mounts, and others resorted to faired-over observer positions to allow dorsal gunners to keep a look out for night fighters below them. The decision to mix in Mosquito night fighters with the bombers also helped, as the slow, docile flight profile required for Schrage Musik attacks left the night fighters in no position to defend themselves. Even so, the Schrage Musik was never fully countered, and it remained an effective weapon right up to the end of the war.

The Bomber Stream

With the Kammhuber Line inflicting ever greater losses upon the RAF’s bombers, a major change in tactics was needed. In the early stages of the war, RAF practices called for bombers to fly individually, with each bomber navigating alone so as to avoid inflight collisions and allow them to better maneuver around air defenses. However, this made the bombers easy targets for Kammhuber’s night fighters. The development of the GEE radio navigation system offered part of a solution by allowing bombers to fly together in formations at night, but standard practices still meant that bomber formations would be vulnerable to enemy fighters. At the end of 1941, RAF officials, following the recommendations of strategist R. V. Jones, looked into a new concept. Known as the “bomber stream,” the practice was less a countermeasure than a brute-force approach. The bomber stream seized upon the limitations of the Kammhuber Line - which could only handle six interceptions per cell per hour - by concentrating bombers into a single cell and overwhelming local defenses. By concentrating hundreds of bombers along the same stream, the bombers could not only reduce losses and overwhelm defenses, but reduce the time the bombers were over their targets from a four-hour window (with the older individual approaches) to just a 90 minute period.

The Bomber Stream would make its debut over Cologne on the last night of May 1942. Under the codename Operation Millennium, Bomber Command would launch the largest raid the world had yet seen. Every single aircraft available was earmarked for the raid, with aircraft and crews drawn from training units and spares. In doing so, Bomber Command was able to field 1,047 bombers - more than double their “regular” strength of only about 400. Though “only” 868 aircraft were aimed at Cologne itself, the new tactic was tremendously effective. 1,455 tons of bombs were dropped on Cologne, two thirds of which were incendiaries. Nearly 13,000 buildings were destroyed, killing nearly 500, injuring 5,000, and displacing 45,000. And for all the damage done, losses were light - just 43 bombers were lost, and only four were downed by night fighters. With a loss rate of under 4% and devastating damage done to Cologne, the Bomber Stream had proven itself.

After the devastating raid on Cologne, Kammhuber was left scrambling to rework the night fighter system. Clearly, the rigidly structured system was not capable of dealing with massive raids like the British had just conducted. The only solution - break the rigid structure and divert all available night fighters to the stream - was itself stretching the abilities of the Kammhuber Line, and, to implement it, Kammhuber needed a major expansion of the air defense network. More powerful Wurzburg sets were brought in to expand the size of individual night fighter boxes, and the boxes were expanded backwards several lines deep to allow night fighters to follow the stream into Germany. The new tactics worked, though it took time for the changes to take effect. Losses slowly crept back up to the rates they were at before the bomber stream was implemented, forcing the RAF to develop new solutions.

Erhard Milch Ruins Everything

Following the disaster that was the 1,000-bomber raid on Cologne, Kammhuber began looking for a new dedicated night fighter to supplement his forces. The appearance of the de Havilland Mosquito that same month would set the de facto requirements for Kammhuber’s new night fighter. A new high-performance machine was needed, capable of carrying all the night fighter equipment for tracking and killing bombers while still being fast enough to intercept the Mosquito. Despite constant contention with the head of the RLM, Erhard Milch, the need for such an aircraft was generally agreed upon. The issue came in procurement. Kammhuber was greatly interested by a design Heinkel had proposed, going as far as ordering it into production without consulting the RLM after seeing the aircraft in November 1942. Milch, who had personally rejected Heinkel’s design earlier that year, had instead favored a competing design from Focke Wulf. Outraged that Kammhuber went behind his back, Milch got Kammhuber reassigned to Luftflotte 5 in Norway while repeatedly trying to cancel Heinkel’s winning design. Only after Focke Wulf’s contender proved impractical and the Ju 388 ended up being failures did Milch finally relent, but by the time production was finally allowed to resume two years had passed and the new fighter would not be able to make a significant impact on the war.

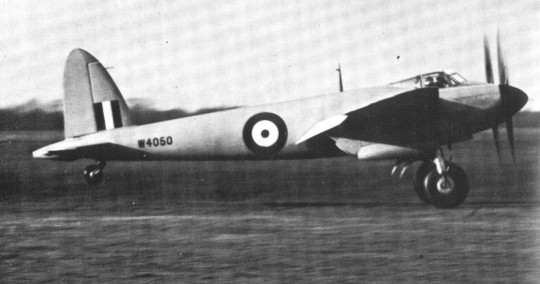

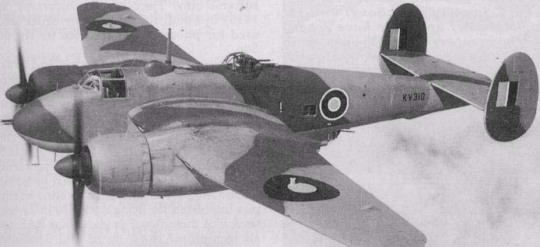

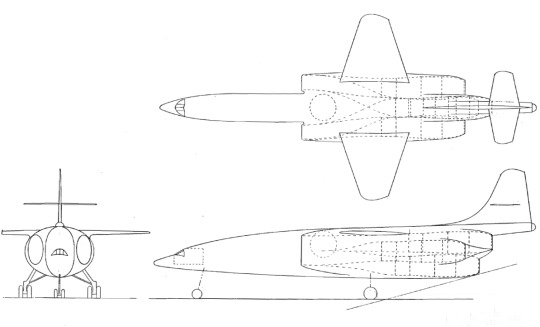

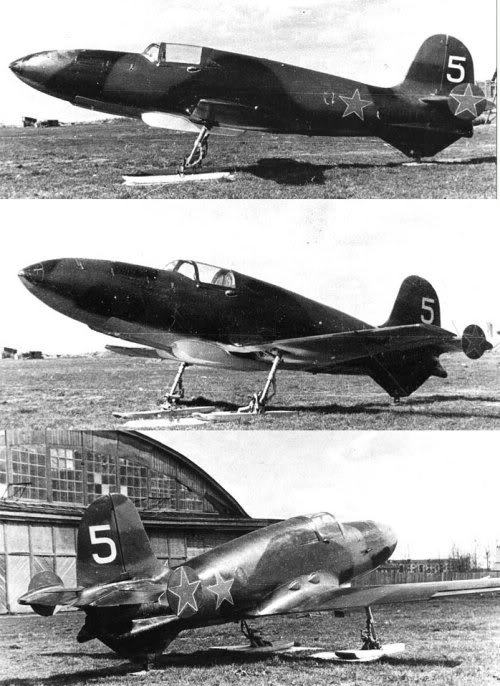

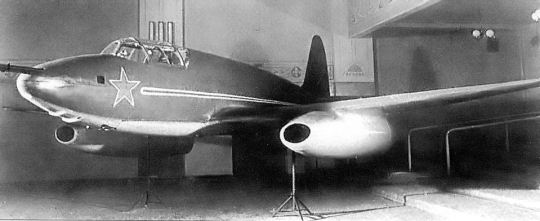

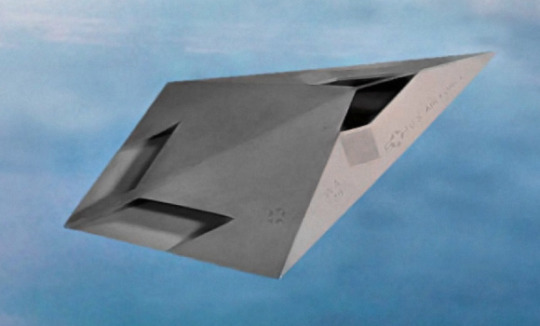

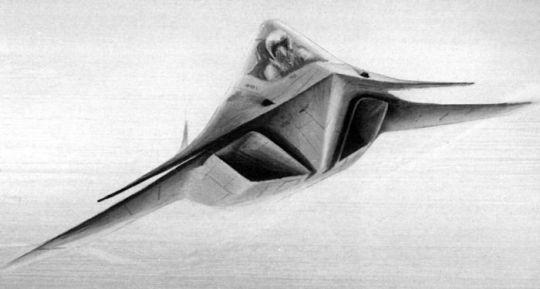

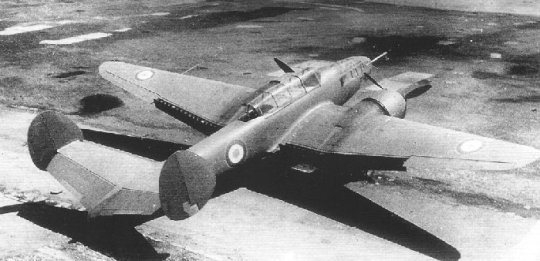

Heinkel He 219

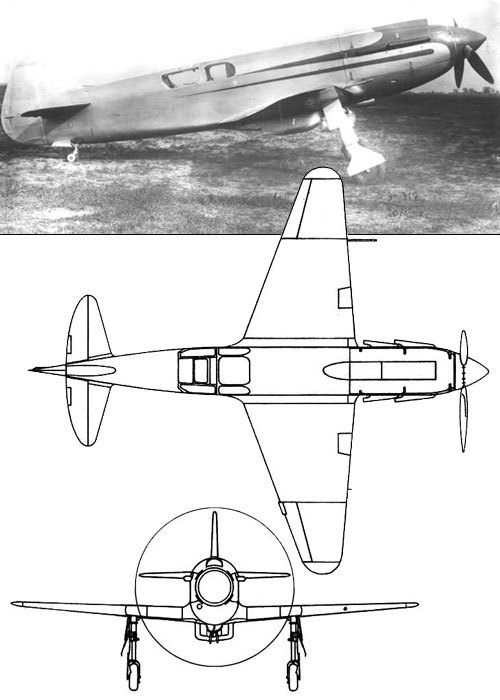

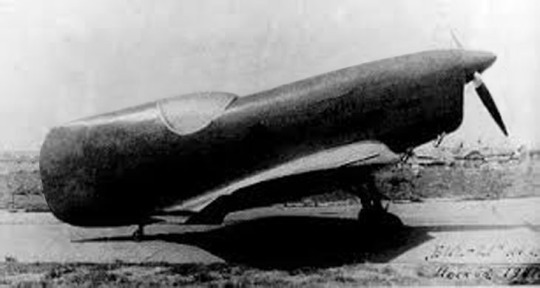

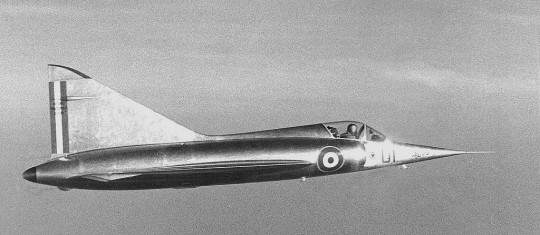

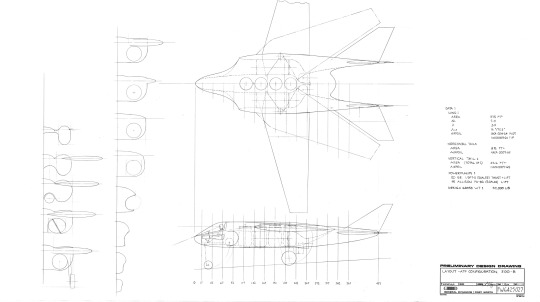

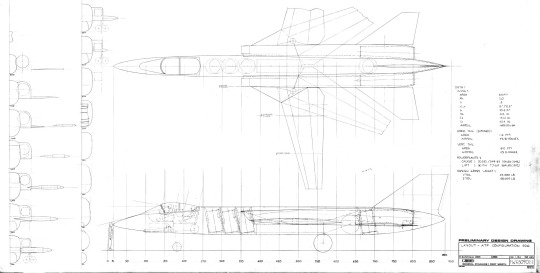

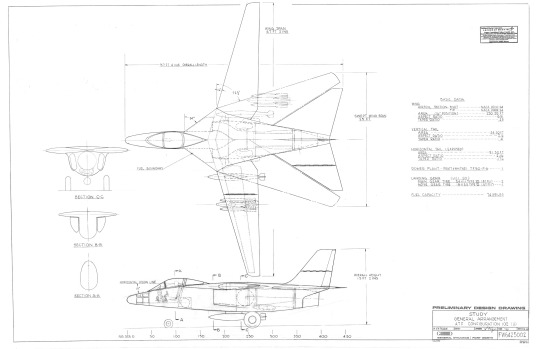

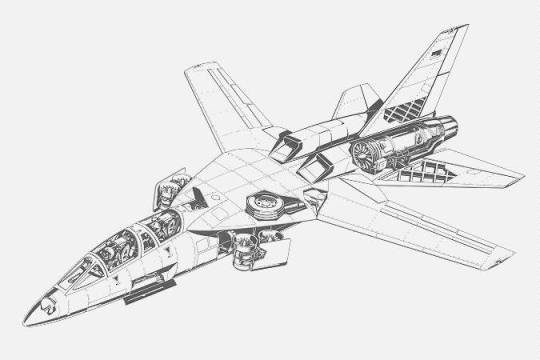

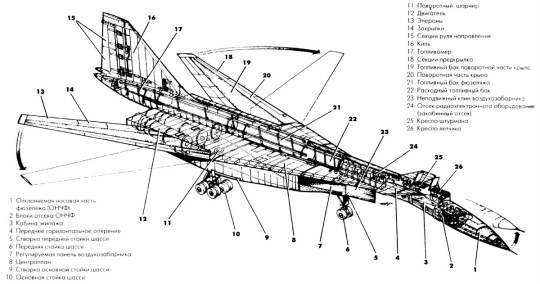

Heinkel’s new night fighter began life in 1938, when Robert Lusser transferred from Messerschmitt and began work on an advanced high-speed bomber project designated P.1055. The P.1055 was to incorporate a host of modern features, including a pressurized cockpit, the first ever ejection seats planned in a combat aircraft, tricycle landing gear, and remote-controlled defensive armament. Powered by the coupled DB 610 engine, it was to have a top speed of 470mph. Unfortunately, the RLM rejected the design when it was first proposed in August 1940 on grounds of its complexity, and even though Lusser reworked it with various new engines and wing planforms, it was again rejected in 1941. However, as Kammhuber began looking for a new night fighter, Heinkel quickly reworked the design to meet the new requirements. The design shrank slightly and used two DB 603 engines with annular radiators. Heinkel saw the design as so promising that he personally funded a prototype while the proposal was sent off to the RLM in early 1942. However, the RLM again rejected the design, opting in favor of Ju 88 and Me 210 variants.

Despite the rejection, Heinkel continued on with the prototype. Because of engine shortages, Heinkel had to make do with a different variant of the DB 603 poorly suited to high altitudes for the prototype. Even then, the engines weren’t ready until August 1942, meaning the prototype wouldn’t fly until early November 1942. The prototype was demonstrated to Kammhuber on November 19, who was so enthusiastic about the aircraft that he immediately ordered it into production as the He 219. Meanwhile, Heinkel refined the design. Defensive armament was removed due to the ineffective mount, and, with weight “freed up,” forward firing armament was increased by adding two 20mm cannon in the wing roots. Combined with the ventral tray carrying four more cannon, the He 219 would have a formidable armament. Being a night fighter, the He 219 also had room for a Lichtenstein radar in the nose.

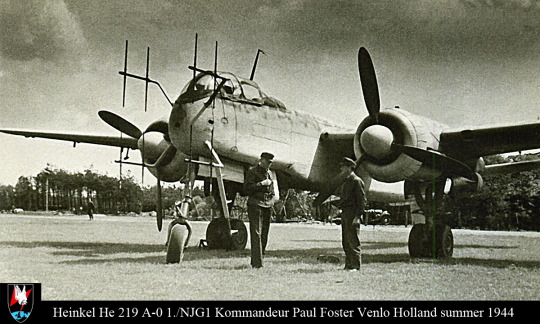

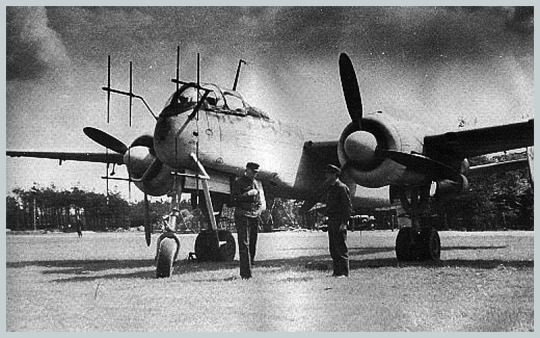

Because of the resistance from Erhard Milch, production proceeded slowly. Though Kammhuber had ordered 300 machines and ultimately hoped for a fleet of 2,000, only three pre-production machines would reach service by April 1943, flying with I./NGJ 1 out of Venlo in the Netherlands. The type’s combat debut came on the night of June 11, when the V9 machine downed five bombers in a little over an hour. In the next ten days, the He 219 continued to excel, reportedly claiming some 20 RAF bombers. Despite an excellent debut, however, the resistance from the RLM and damage done by Allied bombing meant that the first production aircraft wouldn’t reach operational units until October 1943. Though initially intended as a pre-production variant, the He 219A-0 would continue production until mid-1944, with a total of 104 examples built.

The He 219A-2 would be a more refined production model, incorporating longer engine nacelles filled with fuel tanks, improved engines, and provisions for two 30mm Mk 108 cannon in a Schrage Musik mounting. The A-2 also carried the more advanced SN-2/FuG 220 radar, allowing it to evade jamming. Though the heavy night fighting equipment and high-drag radar antennas meant that the He 219 was still too slow to catch the Mosquito, it was far from an unimpressive aircraft. It was a major improvement over the Bf 110s and Do 217s it served alongside, while also still holding advantages over the Ju 88. Thanks to its heavy firepower and expansive fuel tanks, the He 219 was able to engage multiple bombers in a single sortie, making it far more effective than the older aircraft in the inventory.

For all the He 219’s impressive performance, however, it still struggled to catch the elusive Mosquitoes. In hopes of giving the fighter the performance necessary to intercept the Mosquito, the stripped-down A-6 variant was developed. The A-6 was a simple conversion that could be done at the unit level, removing some armament and radio systems to bring the top speed up to 400mph. Though none were produced, several were converted in the field. With the failure of the RLM’s favored night fighters - the Ju 388 and Ta 154 - Erhard Milch would finally relent in 1944 and allow mass production to proceed unimpeded. By then, however, it was too late. Though the He 219 finally offered the Luftwaffe a night fighter capable of intercepting Mosquitoes and competing on even terms with the increasingly common Mosquito night fighters, political infighting had held it back until it was too late. The war ended with fewer than 300 He 219s completed.

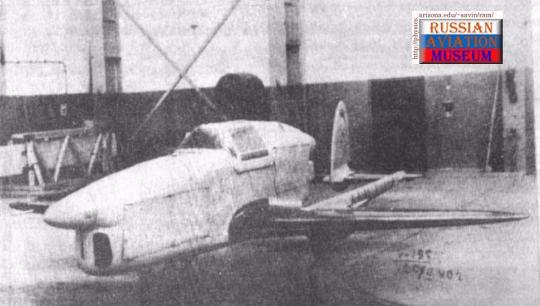

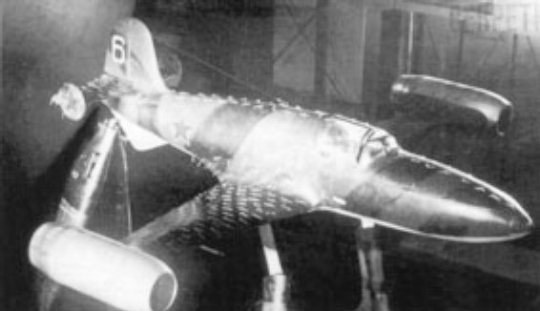

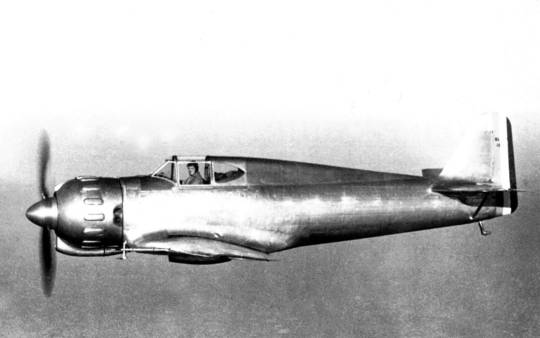

Focke Wulf Ta 154

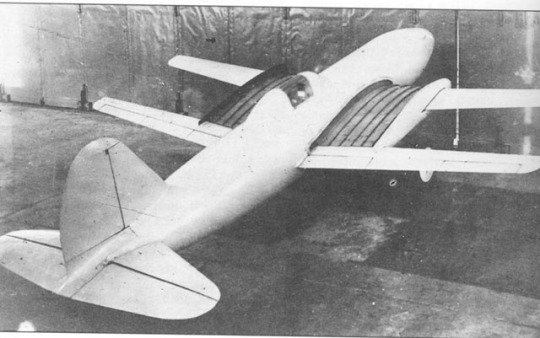

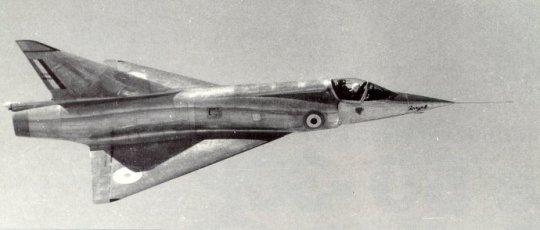

In August 1942, reacting to the appearance of the Mosquito in the skies over Germany, Erhard Milch demanded the development of a similar aircraft for the Luftwaffe powered by the Jumo 211F engine and constructed of the Homogenholz plywood. Focke Wulf would be the first to respond, proposing a high-winged twin-engined fast bomber constructed of a mix of conventional metals and the specified plywood laminate. Initially developed as an unarmed bomber, Milch would request the addition of defensive armament, so two 20mm cannon were to be installed in a tail barbette. Focke Wulf also developed a night fighter version of the aircraft, differing in that it was stripped of its bomb bay and given two forward firing 30mm Mk 103 and 20mm MG 151 cannons, as well as 100kg of armor. When the RLM belatedly issued specifications for a new night fighter to catch the Mosquito, they were practically written around Focke Wulf’s new design. The night fighter variant received an order for prototypes, taking shape as the Ta 154.

The V1 prototype Ta 154 would fly on July 1, 1943. It was sent off for comparative trials against the He 219 and Ju 388, where the unarmed prototype easily outflew the competitors, which were weighed down by armament and radars. The Ta 154 V3 was the first example to be armed and fitted with a radar, and when testing began, the effect was painfully clear. While the V1 was capable of a blistering 700km/hr top speed, the V3’s top speed dropped by 75km/hr, making it only marginally faster than the He 219. Nevertheless, having gained favor from Milch, the Ta 154 was ordered into production, with plans for the production aircraft to mount the more powerful Jumo 213. Thus, while the fifteen pre-production Ta 154A-0s used the Jumo 211s of the prototypes, the uprated engines of production machines would give it an edge over the He 219.

Unfortunately, delays in the Jumo 213 development meant that the engines weren’t ready until June 1944. Just before engines could be delivered, however, the factory making the glue that held together the Ta 154’s wooden structure was bombed out, forcing Focke Wulf to switch to an alternative adhesive that was weaker. Though deliveries finally began in mid 1944, a series of wing failures led to the loss of several Ta 154s - a result of the apparently corrosive nature of the substitute glue. With the Ta 154s literally falling apart and continuing engine shortages plaguing production, Focke Wulf’s Kurt Tank halted production in August, and the RLM cancelled the order for 154 A-1s in September. By then, 50 machines had been completed, and surviving A-0s were brought to the A-1 standard. The extent of their service is unclear - it appears that several Ta 154s did see service with NJG 3, while a few others were used as conversion trainers for jet pilots. However, it’s unclear how many missions they flew, if they downed any enemy aircraft, or even what pilots thought of the fighter.

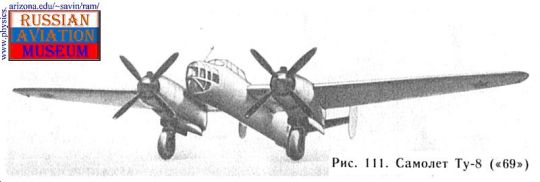

Junkers Ju 388J

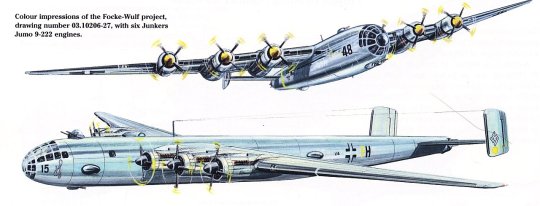

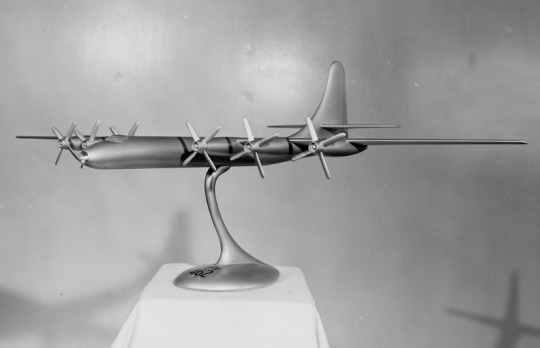

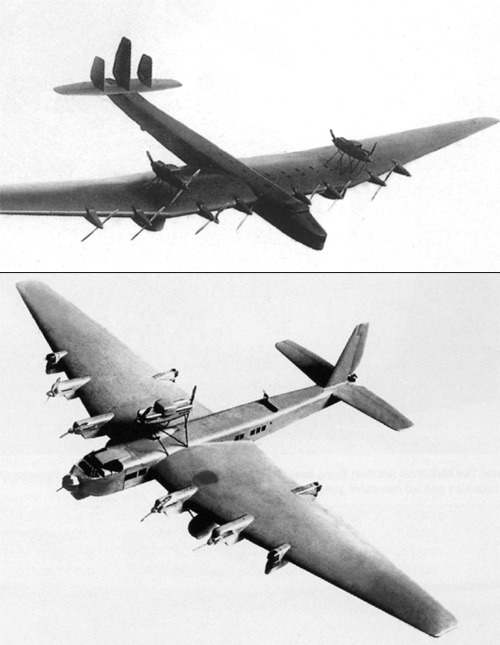

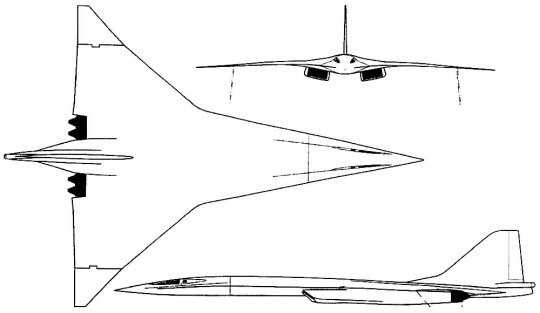

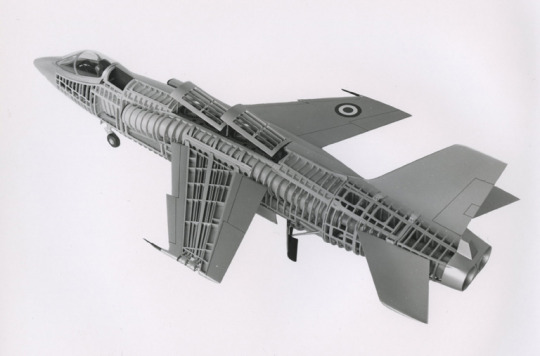

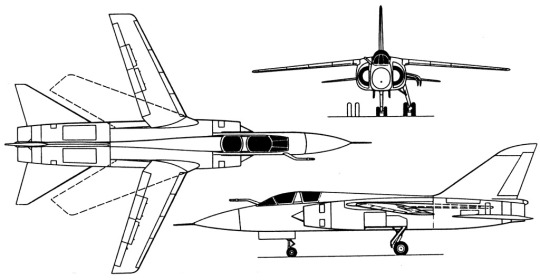

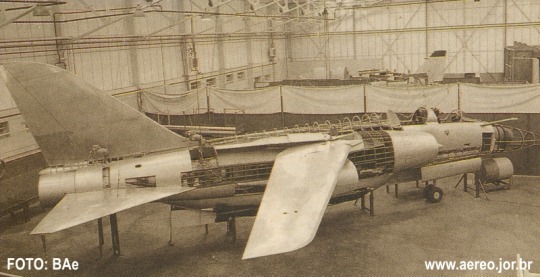

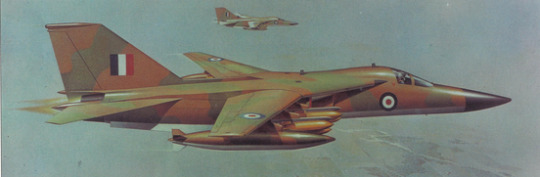

Though the He 219 and Ta 154 were promising designs, they achieved their performance through the use of low aspect-ratio wings, meaning that performance at altitude suffered. The need for a high-altitude fighter actually predated either of the two designs, with development of high-altitude interceptors beginning shortly after Germany learned of the B-29 in late 1942. For high-altitude night fighter duties, Junkers was selected to develop a variant of their Ju 188 high-speed bomber. Becoming the Ju 388, Junkers was to develop not just a night fighter, but also bomber and reconnaissance variants. The general design had the cockpit pressurized and all defensive armament replaced with a twin-13mm machinegun tail barbette that was to be controlled remotely. The Ju 388J would have an all-new solid nose, providing space for two 30mm Mk 103 and 20mm MG 151/20 cannons. For night operations, the Mk 103s were to be switched with shorter-barreled Mk 108s, while two more Mk 108s would be added in a Schrage Musik mount. Space for a radar in the nose was also made.

The first Ju 388 prototype would be a reconnaissance-oriented L model, flying in December 1943. Two Ju 388J prototypes would be made, but by the time production was ready, it was clear that the B-29 was being sent to the Pacific, so production concentrated on the L models. Not only had the need for a high-altitude fighter evaporated, but the RLM had long since relented and approved full production of the He 219 by the time the Ju 388J was ready for production. Due to the disruption caused by Allied bombing, deliveries wouldn’t begin until August 1944. Roughly 47 Ju 388Ls and 15 Ju 388K bombers were completed, but only a single Ju 388J beyond the original two prototypes were finished.

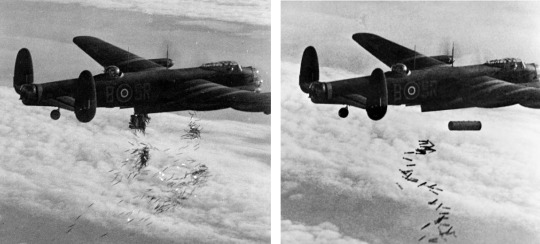

Window

The next groundbreaking countermeasure the RAF would deploy against the Kammhuber Line could trace its origins back to 1937, when British researchers began suggesting deploying wires or foils strips in the skies to create false radar returns. While this seemed promising, development of the concept didn’t pick up until early 1942, when the idea was refined to call for packets of reflective strips to be dropped from aircraft. Working off of data from a Wurzburg radar set that had been captured in a commando raid earlier that year, researchers at the Telecommunications Research Establishment tailored the system to the Wurzburg’s sets. The reflective strips consisted of black paper backed with aluminum foil cut into 27 by 2 cm sections - making their length exactly half that of the Wurzburg’s wavelength for optimum reflectiveness. Though testing showed the concept to be incredibly capable - the Wurzburg would be unable to distinguish between the aluminum strips and actual bombers - it was decided to hold off on the system until bomber losses rose once more. Codenamed Window, the novel new chaff countermeasure would have to wait almost a year before making its debut.

On the night of July 24, 1943, the RAF finally decided to break out Window along with several new jamming platforms to support a new bombing operation against Hamburg. Appropriately named Operation Gomorrah, the operation would last eight days and seven nights, marking the heaviest aerial assault yet launched. 24 aircraft were earmarked to deploy Window, deploying their payloads in a wide swath across the Kammhuber Line. The results were impressive - completely blinded, searchlights scanned desperately and flak fired blindly into the skies. With radar displays overwhelmed, the night fighters were unable to find the bomber stream, allowing the RAF bombers to hit their target over roughly an hour and egress with only 12 of the 791 attacking bombers lost.

Though this first raid already left Hamburg devastated by ongoing fires, it was far from the end. The USAAF hit the city with 90 B-17s that day while Mosquitoes dropped delayed-fuse bombs to hinder firefighting efforts through the day. The fires continued to rage into the next night, putting out a smoke cloud so dense that the planned 700-bomber raid for the night was diverted to Essen. Thunderstorms prevented any significant attacks to be flown on the 26th, but the RAF would sortie 787 bombers on the night of the 27th. Capitalizing on the damage already done to the city that hindered firefighting efforts, the RAF hit Hamburg with incendiaries. The resulting firestorm engulfed over 21 square kilometers of the city. Two more major night raids were launched on July 29 (777 bombers) and August 3 (740 bombers). By the end of the operation, the Allied forces had flown 17,000 bomber sorties and dropping 9,000 tons of bombs for minimal losses - the heaviest losses occurred on the final raid, with only 30 bombers lost. For the Germans, it would be the most devastating bombing raid of the war. 183 of 524 large factories in Hamburg were destroyed, along with 4,118 of 9,068 small factories, complete disruption of local transport, and destruction of over half the dwellings in the city. 42,600 people were killed and 37,000 wounded, and of the survivors, over a million would flee the city for the duration of the war.

Zahme Sau

The immediate reaction of the German night fighter corps following the Hamburg raids was the implementation of the Zahme Sau practice. Zahme Sau dropped the previous means of directing night fighters wherein ground radars rigidly controlled night fighters within their boxes. Instead, upon the detection of an incoming raid, night fighters were scrambled and sent to orbit several radio beacons until the bomber stream was identified. Once the stream was found, all available night fighters were vectored in by Wurzburg radars. The fighters would feed into the stream, operating independently from ground control until fuel or ammunition ran out. Unlike the previously developed counter to the bomber stream, ground based radars were not relied upon as much for intercepts. Instead, they merely directed the fighters in the direction of the stream, with onboard radars doing the bulk of the legwork.

Zahme Sau made its debut on the night of 23/24 August 1943 against a raid on Berlin. Flying against a stream of 727 bombers, the night fighters managed to claim 56 RAF aircraft - a loss rate of 8%. Further improving the chances of interception was the introduction of the Naxos radar detector, which began to reach operational units in September 1943. Though the Naxos was incapable of directing night fighters to individual aircraft, it could detect emissions from the H2S radars on British bombers as far as 35 km out. As the device became more prevalent, the Zahme Sau practice became more effective. Window continued to be a problem, but Zahme Sau would provide the Luftwaffe with a night fighter practice for which the RAF would not be able to develop an effective counter.

Wilde Sau

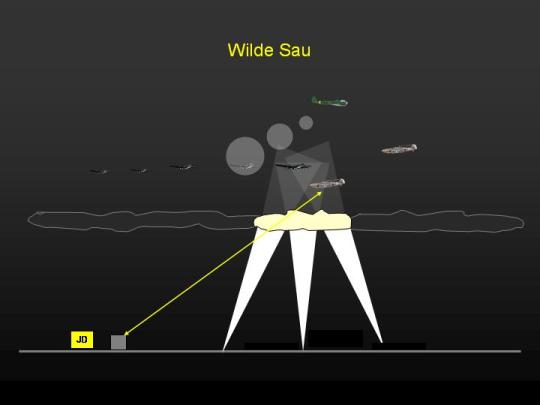

The far more radical reaction to the devastating Hamburg raids was the Wilde Sau practice. Wilde Sau actually predated the Hamburg raid, being proposed by bomber pilot Major Hajo Hermann in early 1943. Wilde Sau completely dropped the use of airborne radars, instead opting to fly unmodified single-engined fighters. Ground controllers would direct the Wilde Sau aircraft to the bomber stream via radio, at which point the fighter would identify and engage targets visually. To provide adequate lighting for the fighters, the target city would produce as much light as possible to illuminate the sky - going completely against all established doctrine. By flying above the bomber stream, the fighters would then be able to identify the bombers over the illuminated city, at which point they would dive in and engage.

Unsurprisingly, this new concept was hardly popular amongst officials. Such an unorthodox practice was incredibly dangerous, not just because pilots were being drawn from daylight fighter units, but because operations were to be flown exclusively over the flak-filled skies above Germany’s cities. City officials resisted the call to illuminate themselves, so large numbers of searchlights would have to substitute. Nevertheless, Major Hermann’s Wilde Sau concept gained traction. In late June 1943, a test unit was established, drawing pilots and aircraft from JG 1 and JG 11. Known as JG Hermann, they would make their debut over Cologne in early July, flying against 653 RAF bombers. Working with the illumination provided by searchlights, target-marker flares, and fires in the city, the Wilde Sau fighters claimed 12 bombers - shared with ground-based flak. To prevent friendly fire, flak was limited to a certain ceiling, above which the Wilde Sau would operate.

The relative success over Cologne seemed to have validated Hermann’s proposal, leading to the expansion of JG Hermann into a full-fledged Jagdgeschwader - JG 300. Initially, they performed well. They accounted for several bombers downed during Operation Gomorrah, and through August and early September they were regularly claiming more than 10 aircraft per raid. On the night of August 23, 1943, over Berlin, Hajo Hermann himself led the Wilde Sau on their most successful operation ever, claiming 57 RAF aircraft. In September, JG 300 were followed by JG 301, and in November, JG 302 was formed. The Wilde Sau force came under the command of 30. Jagddivision, which commanded the three Wilde Sau Jagdgeschwader, as well as III./KG 3, which was tasked with dropping illumination flares over bomber streams to support the fighters.

Unfortunately, Wilde Sau was far from sustainable. As the daylight campaign picked up, the pilots of 30. Jagddivision found themselves flying day and night, leading little time for rest and maintenance and leading to high attrition. Poor weather in the Fall and Winter of 1943 led to reduced effectiveness and high accident rates, and, as American fighters began to attain air superiority, losses mounted. With the Zahme Sau proving more effective, the Wilde Sau Geschwader were increasingly relegated to daylight missions. Night operations became scarce, and their strength was drained away by American fighter escorts. JG 302 was folded into JG 301 at the end of 1944, and JG 300/301 would fly almost exclusively daylight missions in the last year of the war.

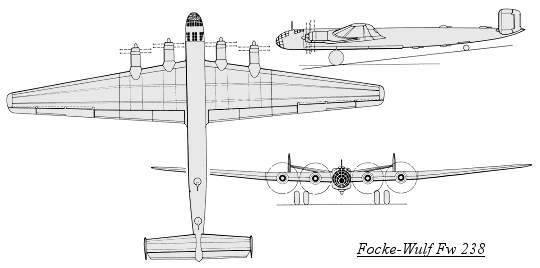

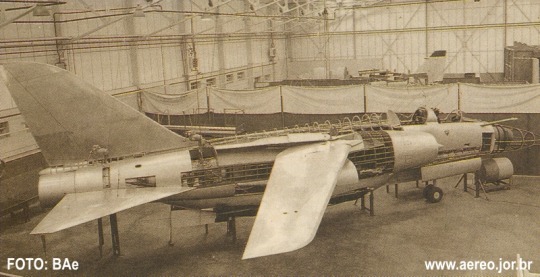

Dornier Do 335

The promising Do 335 tandem-engine heavy fighter would be selected for development as a night fighter sometime in the winter of 1943/44. In mid-January 1944, the RLM ordered five prototypes to be built as night fighters. Unfortunately, Allied bombing seriously hampered production, meaning that these were never completed. Nevertheless, Dornier did make plans for full production night fighters. The Do 335A-5 was slated to be a single-seat machine, while the Do 335A-6 would be derived from the two-seater trainers. Though there was no space in the nose for radar equipment, Dornier apparently planned to mount radar antennas on the aircraft by splitting them across the wings. Thus, the fighter would still be able to use the ubiquitous Liechtenstein and Neptun radars. However, none of these materialized - the limited Do 335 production that took place before the end of the war concentrated on the A-1 series fighter bombers.

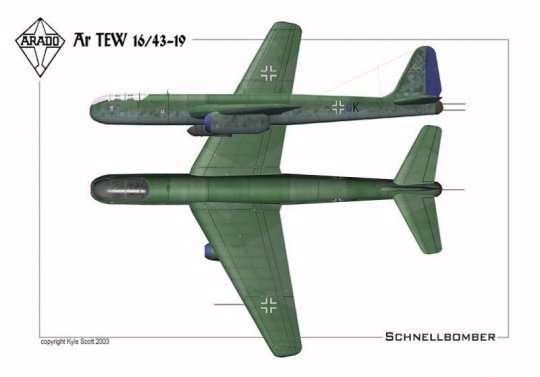

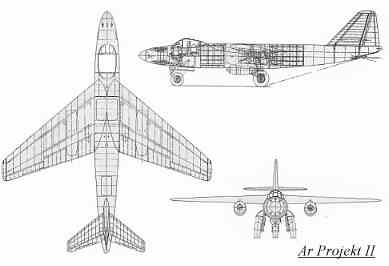

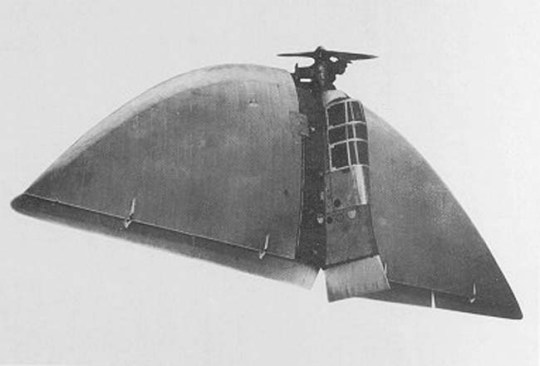

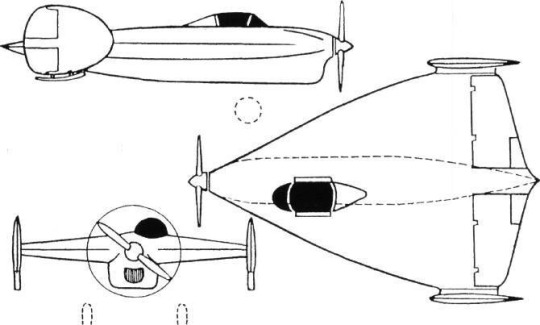

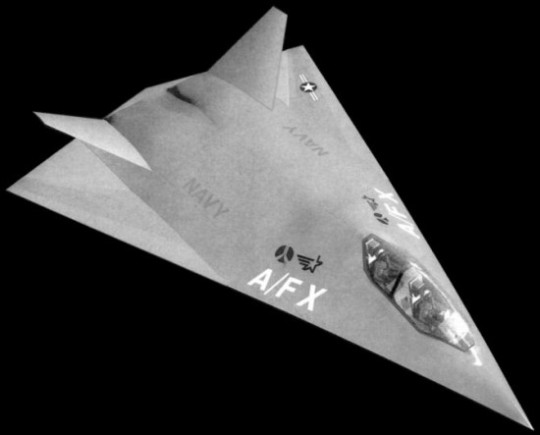

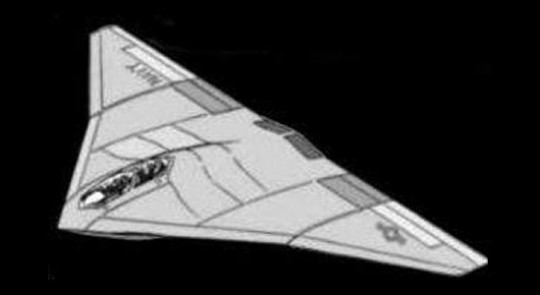

Arado Ar TEW 16/43-19

In August 1943, Arado began work on a new multirole jet aircraft. Designed around an all-metal mid-winged monoplane layout, the new aircraft would be powered by two jet engines and feature a crew of two in the nose. Three variants were proposed - a bomber, heavy fighter, and night fighter. The night fighter variant would mount two 30mm Mk 108 cannon under the nose, as well as three 20mm Mk 213 cannon in a ventral pack and two more Mk 213 on the sides of the nose. Provisions were also made for two Schrage Musik Mk 108s behind the cockpit, and the defensive tail barbette seen on the other variants was retained. For night fighter operations, a Berlin radar would be carried in a radome in the nose, and a radar operator would be placed in a compartment aft of the wing to operate the equipment. Unfortunately, the design never materialized, as the success of the Ar 234 and Me 262 made the design surplus to requirements.

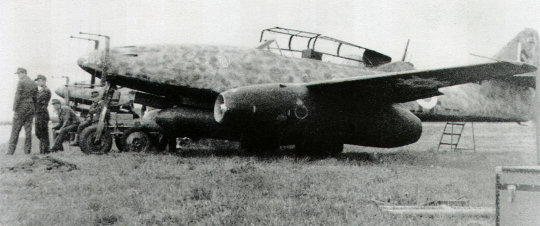

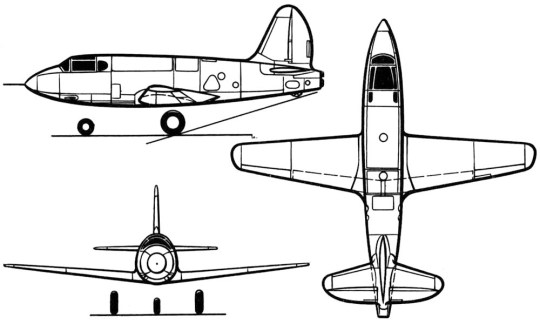

Messerschmitt Me 262B

In the Summer of 1944, Messerschmitt had produced the two-seat Me 262B-1a trainer. Though only about 15 were built, the two-seat Me 262 showed promise, offering far better performance than contemporary night fighters while still being able to mount an air intercept radar. To experiment with the concept, an Me 262B-1a was converted to the B-1a/U-1 standard, with a FuG 218 Neptun radar installed in the nose and a Naxos radar homing system. Because of the space taken up by the radar equipment, armament was reduced, but still heavy - two 30mm Mk 108 and two 20mm MG 151. Trials of the new night fighter began in October 1944, flown by Hajo Hermann. Though performance was cut by the protruding radar antennas, the Me 262B-1a/U-1 remained a capable machine, putting its performance far beyond that of the Mosquito night fighters that were devastating the night fighter corps.

As the two-seater night fighter continued trials, the single-seat Me 262 fighter made its debut as a night fighter. Led by Hauptmann Kurt Welter of NJG 11, a handful of Me 262As began Wilde Sau operations in December 1944. Wilde Sau operations concentrated on hunting down the elusive Mosquito pathfinders, with Welter himself credited with three such aircraft by February. Once the Me 262Bs finished testing, they too were passed onto NJG 11. Seven of these entered service in April 1945. Unfortunately, details of their service are scarce, and, reaching service in the last month of the war, they likely saw little use. As these seven two-seaters were on their way into service, Messerschmitt was also working on a more refined Me 262B-2a. Intended to be the definitive production variant, the Me 262B-2a would have a longer fuselage to increase fuel capacity and a new nose capable of carrying either the Neptun radar or the new Berlin centimetric radar. Additionally, the fighter would have provisions for Schrage Musik guns behind the cockpit. Unfortunately, the war ended before any of these could be completed.

Arado Ar 234B-2N

In September 1944, engineers at Arado proposed a night fighter variant of their jet bomber. Designated Ar 234B-2/N, the bomber would be fitted with the FuG 218 Neptun radar in the nose and a pair of 20mm MG 151 in a ventral gun pod. To accommodate the radar operator, a cramped compartment behind the wing was installed. Though hardly an ideal arrangement, it gained enough traction for two prototypes to be ordered. These two prototypes were sent to Kommando Bonow, where they would perform operational trials. Tests began in March 1945, but it was very quickly determined that the aircraft were unsuitable for night fighter operations. Operational trials ended quickly, and no victories were claimed by the aircraft.

Berlin

In early 1943, a Short Stirling Pathfinder, complete with its advanced H2S radar, was downed near Rotterdam. The radar system was pulled from the wreckage mostly intact, allowing technicians to analyze the system. The most important piece pulled from the H2S radar would be its cavity magnetron, which allowed the system to produce centimeter-wavelength signals in a fairly compact package. Developing detection equipment for the H2S was a fairly simple endeavor - the FuG 350 Naxos radar detector would be operational by September. However, creating an air intercept radar out of this captured system was a far more complicated project. Though Telefunken would largely copy the British design, it took nearly two years to complete what became the FuG 240 Berlin radar. The Berlin was a compact system with a .7 meter dish antenna. With a 10cm wavelength, it had a range of up to 9 km. Most importantly, however, it was compact enough to be contained under a radome, allowing for drag to be greatly reduced on night fighters. Unfortunately, development dragged out for far too long. Production didn’t begin until the Spring of 1945, and the first units weren’t installed on combat aircraft until April 1945.

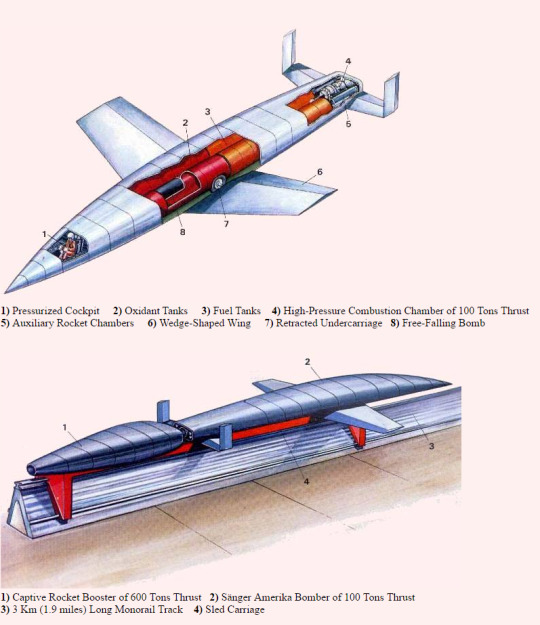

The 1944 Night Fighter

In January 1944, the Technical Air Armaments Board of the RLM issued requirements for a new night fighter. Calling for a top speed of 900 km..hr and endurance of four hours, the new fighter was to have an armament of four cannon and the ability to carry a FuG 240 or FuG 244 radar. Dornier, Arado, Blohm & Voss and Focke Wulf all produced designs. All of the proposals were wildly unconventional, ranging from mixed-propulsion aircraft to full jet-powered designs. Development would go on for over a year without any prototypes materializing before the RLM dropped the requirement, replacing it with a new specification that called for far higher performance than any of these proposals could hope for.

Messerschmitt P.1099B

Messerschmitt would begin work on a two-seater multirole development of the Me 262 around the same time as the new night fighter requirements were issued. While a wide variety of armaments were proposed, Messerschmitt’s night fighter development of the design was surprisingly simple. With a solid nose capable of holding a radar, the night fighter P.1099B proposal completely eliminated the elaborate remote-controlled defensive armament of the other designs, instead replacing it with a simple arrangement of two forward firing and two Schrage Musik 30mm Mk 108s.

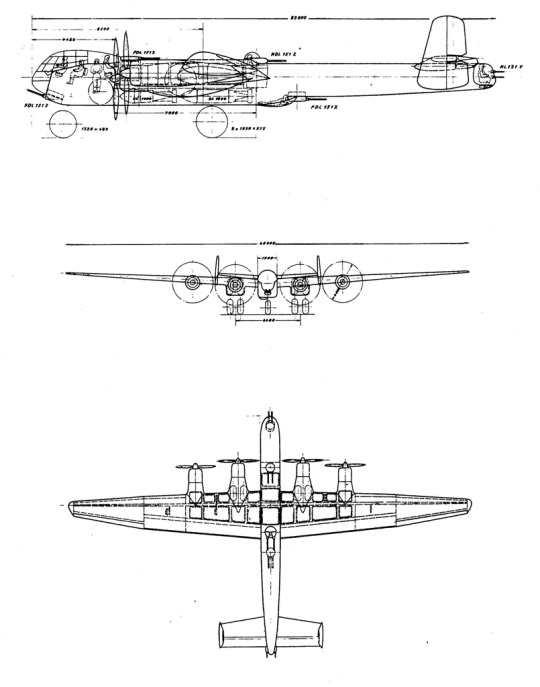

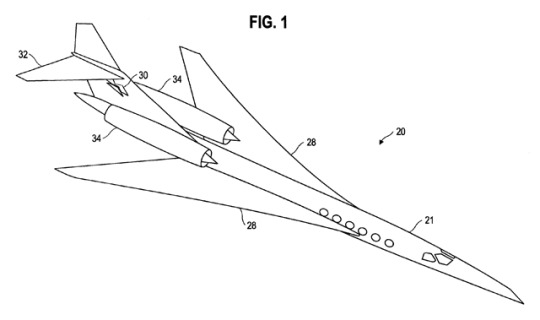

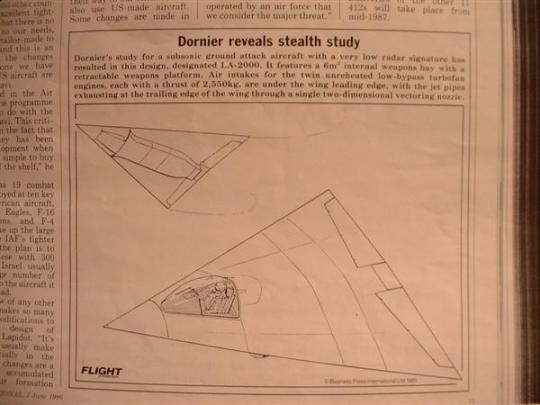

Dornier P.252

Dornier’s night fighter proposal actually predated the requirements, with Dornier repurposing the design as a night fighter once the RLM issued the specifications in early 1944. The P.252 morphed into three proposals all based off the same general design. A long, slender fuselage would carry a crew of three and two Jumo 213J engines in tandem geared aft to drive contra-rotating propellers. A cruciform tail would protect the propellers from ground strikes. The three proposals differed mainly in their wings. P.252/1 had fairly straight wings, while P.252/2 made use of high aspect-ratio swept wings. P.252/3 also used swept wings, but with a reduced sweep and broader chord. Armament was to be heavy - four forward firing and two upward firing 30mm cannon. Unfortunately, despite the promise of the design, it gained little traction among an RLM now firmly set on procuring a jet aircraft. Thus, Dornier was forced to abandon the proposal.

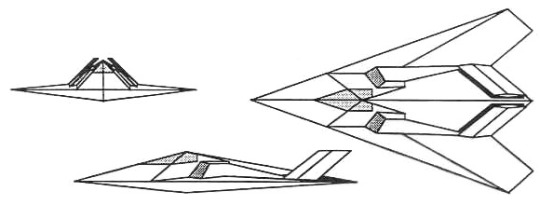

Blohm & Voss P.215

Blohm & Voss would derive their night fighter proposal from the P.122 single-seat fighter. The fuselage of the P.215 was a compact nacelle, containing the crew of three, two He S 011 engines, and a nose-mounted radar. The P.215 lacked a tail, instead relying on the outer sections of its swept wings to provide pitch control. The crew sat in a pressurized cockpit, with pilot and radio operator sitting side by side and radioman facing backwards, controlling a remote-controlled dorsal barbette. A variety of armaments were envisioned, ranging from up to six forward firing 30mm cannon to two 55mm cannon or even several Schrage Musik guns. The P.215 was also designed with ease of transport in mind, with the aircraft able to be transported without any special equipment once the wings were removed. Development work continued until late February 1945, when the specifications were updated. The P.215 fell short of the new requirements, but it still offered far better performance than the other designs it was developed alongside. Likely because of this, it was chosen for further development in March 1945. By then, it was too late. The P.215 would never leave the drawing board, coming to an end when Germany surrendered.

Arado Projekt I

Arado’s first submission to the new requirements would be a sleek tailless design. Powered by two BMW 003A turbojets mounted under the fuselage, the night fighter would have its crew of two sitting side by side in a pressurized cockpit. Four 30mm Mk 108 cannon were mounted in the nose along with a Berlin radar. Provisions were also made for Schrage Musik guns, as well as a small payload of bombs. Unfortunately, when looked over by Luftwaffe officials, several major shortcomings were found. Poor intake design would hurt engine performance, and the small vertical fins on the trailing edges of the wings were deemed to be inadequate. When the Luftwaffe revamped night fighter requirements in early 1945, this proposal was dropped.

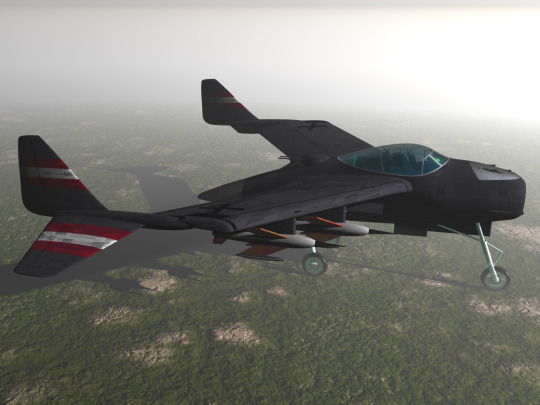

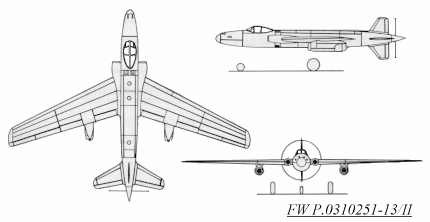

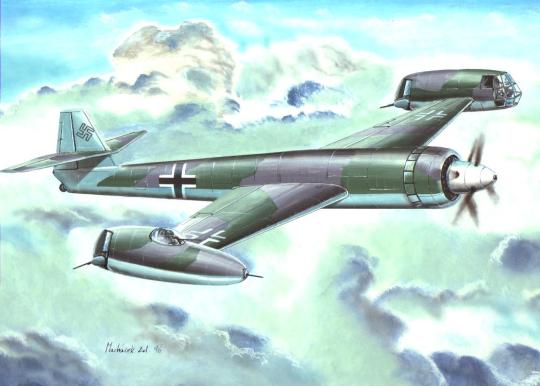

Focke-Wulf 1310251-13/II

Focke Wulf would propose a mixed-construction design for the new night fighter requirements. Vaguely resembling Dornier’s P.252 with its swept wings and pusher propeller, Focke Wulf’s design was to be powered by a single piston engine in the center of the aircraft and a BMW 003A turbojet slung under either wing for high-speed dashes. A crew of three would sit in a pressurized cockpit near the nose, while an armament of up to four 30mm cannon could be carried around the nose. Alternatively, two of the nose guns could be switched out to allow for two to be mounted in a Schrage Musik configuration. The designation of the design is unclear. Focke Wulf did produce three slightly different variants of the design (differing in their choice of piston engine), but it appears that all that has survived of the aircraft is a few design drawings. Thus, the design is known only by the drawing number of one of the surviving documents.

Collapse of the Kammhuber Line

While the Luftwaffe was doing a reasonably good job at keeping pace with British countermeasures and inflicting heavy losses on RAF bombers, the changing strategic situation would be their undoing. Attrition of men and crews was unusually high through the winter of 1943/44 due to poor weather, and as Allied bombing took its toll on aircraft production, replacements became scarce. In just the first 3 months of 1944, 15% of the night fighter crews were lost. The night fighter corps was always lowest on the Luftwaffe’s priorities, so when shortages set in, the night fighters suffered the most. Things only worsened with the introduction of the Mosquito night fighter escorts in mid 1944, which presented the Luftwaffe with something for which they had no real counter. Soon afterwards, oil shortages began to hit the night fighter corps hard, leaving them without enough fuel to train their crews. From then on, effectiveness only continued to decline, with fuel shortages ultimately getting so bad that even the regular patrol methods had to be abandoned.

As the Luftwaffe’s night fighter corps declined in quality, another major blow was dealt to them. The liberation of France and the Low Countries saw Allied forces encroach on the leading elements of the Kammhuber Line. With every mile the Allies advanced eastwards, the Kammhuber Line deteriorated. Just as bad, the advancing Allies brought night fighter airfields ever closer to the front. The night fighters would gradually find themselves subject to night intruder raids, forcing ground crews to seriously restrict lighting at airfields. Even with the declining situation, overall numbers increased - from July to October 1944, the night fighter corps went from 800 to 1,020 aircraft. With their early warning network gone, however, this made little difference. By the new year, significant numbers of aircraft were tasked with North Sea reconnaissance to pick up incoming bombers. Night fighter operations in the new year were sporadic. With no more Kammhuber Line to direct them and quality seriously hampered by shortages and inadequate training, the last months of the war was the Luftwaffe’s night fighters reduced to little more than a harassment force. Though they posed no threat on a strategic level, they continued fighting where resources held out right up until the war’s end.

Late War Night Fighters

As the war situation worsened, the RLM revamped their night fighter requirements. Though exact specifications are unclear, the general trend was to increase all requirements. New requirements called for a much faster night fighter, well beyond the capabilities of those then in development. Rather than follow the trend of most late-war fighter programs, this final round of night fighter development would not simplify demands to account for Germany’s rapidly declining industrial capacity. Rather, they continued with demands for advanced, complex designs, taking full advantage of all technology available at the time.

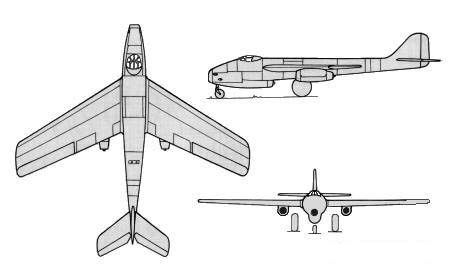

Arado Projekt II

Arado’s final night fighter project of the war would be a fairly conservative proposal. Known as Projekt II, the fighter was a simple twin-engined high-winged design. The crew of two would sit in a pressurized cabin with ejection seats, and a BMW 003A or He S 011 turbojet slung under either wing would power the aircraft. The wings were swept back 35 degrees with the intention of improving performance at high speeds, and armament was to be four 30mm Mk 108 in the nose placed round a Berlin radar. Unfortunately, this design would not progress past the drawing board before the end of the war.

Dornier P.256

Dornier’s contender to the new night fighter requirements was perhaps the most realistic. Broadly derived from the Do 335, the P.256 was to be powered by an He S 011 turbojet under either wing. Because the piston engines were removed, the fuselage was heavily reworked - the cruciform tail gave way to a more conventional one, and the space made in the nose allowed Dornier to fit a radar and several 30mm cannon in it. The crew compartments were also heavily reworked, with the pilot and radioman sitting side by side in a pressurized cockpit in the forward fuselage, while the navigator had his own station facing aft in the rear fuselage. Unfortunately, while the P.256 offered the easiest way to get a night fighter into production (given that it was heavily derived from something already in production), its unswept wings meant it would fall well short of performance requirements. Thus, it was rejected.

Focke Wulf P.011-47

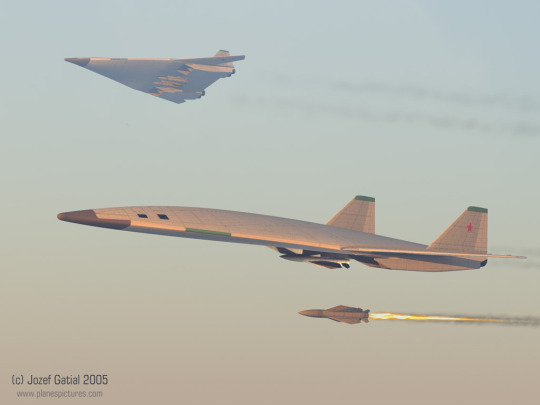

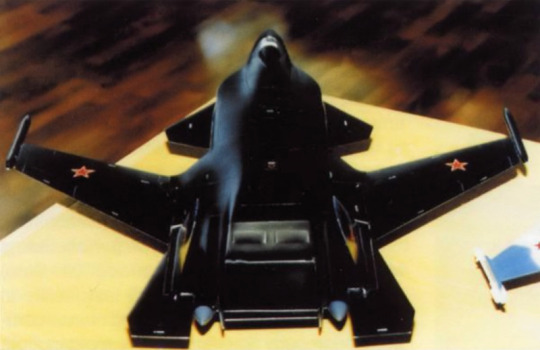

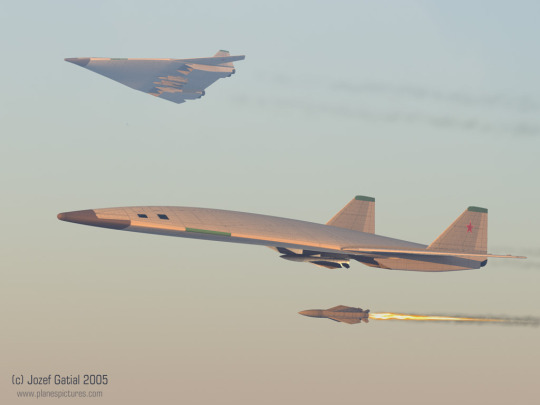

Focke Wulf would produce a unique three-engined design of mixed construction for the new night fighter requirements. The P.011-47 was fairly conventional in layout, being a mid-winged monoplane with 30 degree swept wings. A single He S 011 turbojet was mounted in the nose, exhausting under the fuselage, while another was carried under either wing. The crew of three sat in a pressurized cockpit in the nose, and a radar would be carried above the nose intake. Two 30mm cannon were to be mounted in the nose, while two more would be carried in a Schrage Musik mount behind the cockpit. The aircraft also had a unique flight profile planned - at least one engine could be shut down inflight for more efficient cruise while still allowing the fighter to perform high-speed dashes. Like the competing designs, it would not materialize before the end of the war, though the design did fall into Soviet hands, where it had significant influence on Soviet postwar all-weather interceptor designs.

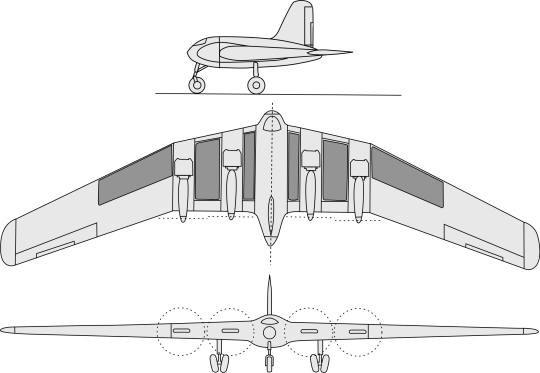

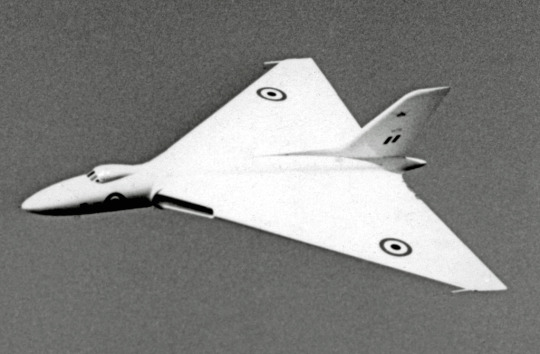

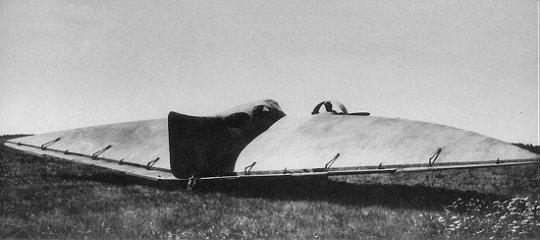

Heinkel P.1079

Heinkel’s final night fighter designs would be a series of design studies known as P.1079. All three P.1079 studies would be two-man machines with a 35 degree swept wing powered by an He S 011 turbojet in either wing root. P.1079A was the most conventional, using a long fuselage, wings with no dihedral, and a V-tail. P.1079B shortened the fuselage and replaced the tail with a single vertical surface, while the wings were given a gull-wing layout, and the P.1079C refined this further into a sleek pure flying wing. While Heinkel seems to have developed these studies fairly far, they don’t seem to have been submitted to the RLM, and they never left the drawing board before the war’s end.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

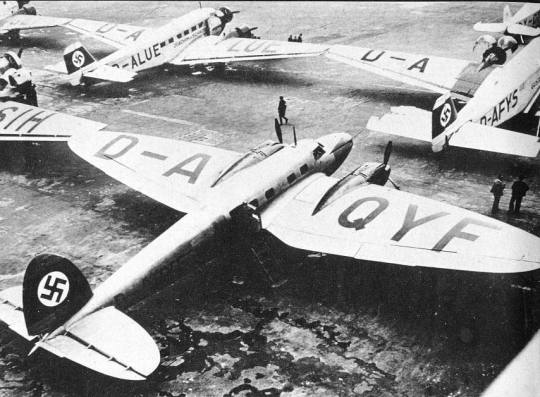

/k/ Planes Episode 102: German Bombers

It’s time for another episode of /k/ Planes! This time, we’ll be looking at the bombers of the Imperial German Air Force and the Luftwaffe.