Quote

We're told, "If you work hard, you'll get results." But for my family, there haven't been any results - just survival.

Jairo Gomez (7 Kids, 1 Apartment: What Poverty Means To This Teen)

0 notes

Quote

I don’t feel this is my family . . .. I feel I’m in the middle and most people just fall away from me. I feel so...I don’t feel loved.

(A child under the care of foster parents in Biehal’s [2014] study)

0 notes

Text

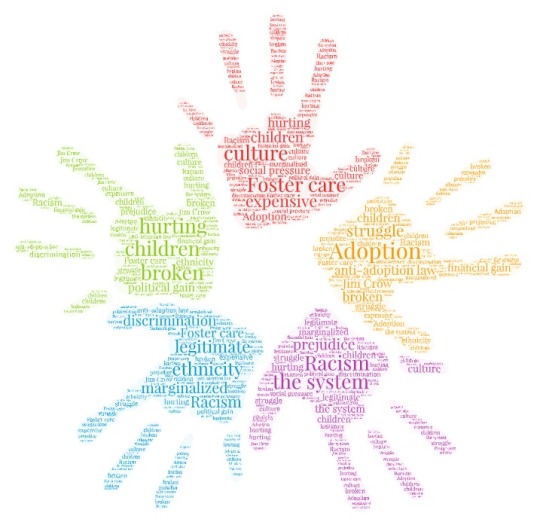

For our Zine, entitled, “Marginalized Family Groups,” we compiled separate essays all relating to the topic of experiences of marginalized family groups. These groups included foster children, families in poverty, adoption, and families that have a child with a disability. All of our essays seek to explore these families' unique experiences and how they face things that other families do not. We also discuss how the “system” or our society and the social services that our country institutes often fail to provide adequate support to these family groups. This lack of support causes problems that are unique to these family groups.

Children in the foster care system can face many adversities. One difficulty that is not considered in most discussion on foster care is the loyalty conflict that the children face when transitioning to a new home. In this zine, Emily will consider how the normalized definition of family plays a troublesome role in the transition to a new home, and how the transition challenges children’s mental health and physical well-being.

Families experiencing poverty continues to be a problem in America that lacks concern from the public and neglects to be addressed by the government. Abigail will discuss the reality of the ways in which the system created to assist those in need, ends in a continuous cycle of financial vulnerability. She will then present the ways in which this cycle is handed down from generation to generation and how this effects the children of these impoverished families.

Greer discusses the role of policy and law in the process of adoption and how the adoption system continuously marginalizes children of color. Systemic racism has contributed to the impacts of the adoption system on marginalized children. She takes a historical approach to examine how the impacts of racially charged law impacted adoption during the Civil Rights era and its lasting impact on adoption and adoptive policies today.

Families with a member with a disability often face many problems within the U.S. educational system, specifically in getting proper services for their child. Abby will explore how fathers in particular fight normative gendered roles in navigating educational planning meetings and how they struggle with communicating with educators. She will also investigate the reasons why families choose to move to new neighborhoods to get their child in an inclusive school or program. In making connections to other marginalized family groups, she will also explore how poverty impacts these families in unique ways. Abby will also consider how policy changes could positively impact the lives of these families by making educational services more accessible both to parents and their children.

The families we discussed in our zine are important to acknowledge and should be examined further, as they are real people with real struggles. We should seek to learn more about the experiences of these families in order to best support them. We also need to address the system that we live in and how it contributes to the problems that these families face. Listening to these families and their unique perspectives on the world will allow us to understand how we can create positive change in our society to improve the lives of others.

Created by: Emily B., Abigail R., Greer A., Abby N.

Sociology of the Family 2021

0 notes

Photo

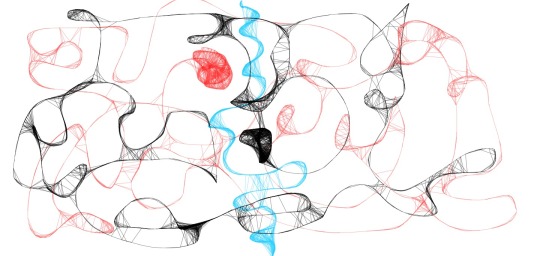

Synthesis

Synthesis represents the struggles and crises of identity that accompany a child in a foster care family, especially through the entanglement of loyalties to both birth and foster families.

- Emily B. 2021

0 notes

Text

The Effects of the Loyalty Conflict on Children in Foster Care - Emily B.

The definition of family has changed immensely over time, and it is continually changing at a rapid pace. More recently, the definition has broadened to extended family, nonrelatives, friends, roommates, coworkers, and the list goes on. As the societal definition of family broadens, so too should it encapsulate the discounted or ignored marginalized family structures. Children in the foster care system face a unique challenge to the familial definition. As young children in foster care are transplanted from a birth family to a foster care family, they not only experience a family dynamic that could be much different from their birth family, but can also change schools and neighborhoods. All of the rapid changes that these children face can lead to shaky ideas of identity, loyalty, and self-awareness. Any fluid family structure can produce confusion over loyalty and trust in a young child, but the loyalty conflict among children in the foster care system have been of pique interest. When children face a loyalty conflict, the effects go beyond an internal struggle; studies have shown that the loyalty conflict can affect the child’s well-being, sense of belonging, and even physiology.

Many factors contribute to the severity of a child’s loyalty conflict, if they confront a conflict at all. Older children can have an easier transition to a foster care family because they are aware of their situation and more receptive towards a stable household, and likely, a better school and neighborhood. The circumstances that led to foster care placement is also a significant factor in how the child takes to their new carers (Maaskant et al., 2015). A heavily studied factor that influences a child’s sense of belonging is the frequency of visits with the birth parent(s). The parental visits are widely debated, with some researchers suggesting that any visits at all can cause harm to the child, while others believe that to cut off visits entirely is more detrimental to the child’s well-being (Biehal, 2012; Fawley-King et al., 2017; Fossum et al., 2018).

The well-being of a child in foster care is influenced by an amalgamation of inherent parts of the foster care system, such as parental visits and a new environment. Maaskant et al. (2015) surveyed children and found that those with high senses of loyalty towards foster parents also felt high senses of loyalty towards their birth parents, but the children exhibited a stronger attachment to the foster parents. The children knew that they were able to rely on the foster parents more, and the researchers concluded that the child’s well-being related mostly to the relationship with the foster parents. Of course, not all children are able to compartmentalize feelings and needs, but some children are able to differentiate the two and ameliorate the chance of loyalty conflicts. The relationship between the child and birth parent(s) can also dramatically affect the transition into a new family. When Dansey et al. (2018) interviewed children that were placed in foster care by intervention of Child Protective Services, they found that many children could not explain why they were put into the foster care system and even idealized the relationship with the birth parents. The children lacked coherent narratives of their reality, meaning they could have issues with self-identity and loyalty conflict could exacerbate this false impression. Parsing through who to rely on can be hard to figure out when both families are integral to a child’s life, and when having to consider one’s well-being can make the loyalty conflict even harder.

Closely related to a child’s well-being is their sense of belonging in their new home; a sense of belonging can be determined by emotional dependency and foster parents’ inclusivity of the child. Children have a sense of their birth parents and can directly compare that to their foster care parents. The perception of each family can inform children on who to rely on in times of need or distress, and children are good at understanding this. Perception of either parents can hurt or help loyalty conflict. Emotional dependence is also influenced by the birth and foster care parent’s reception and handle of the child’s needs. Biehal (2012) studied children’s sense of belonging in long-term foster families and found that most of the participants fell into a “qualified belonging” category. This category included children who reported that their placement felt like belonging in a family, but these children held unresolved feelings (anger, hurt, resentment) toward their birth parents and showed evidence of loyalty conflict. While these children had every reason to attach fully to their foster parents, unresolved feelings can lead to isolation or detachment. Maaskant (2015) reported that most of the children trusted their foster parents and saw them as less vulnerable than their birth parents, and the children who trusted their foster parents felt more accepted by them as well. Acceptance and dependability of parents largely instructs a child’s place in the family and whether the child, themself, feels that they belong.

Studies have proven that the confusion and stress children experience when transitioning to or from birth parents can be seen at the molecular level. Researchers studied children living with birth or foster care parents, following an incident with Child Protective Services. Salivary samples were taken to measure cortisol levels at morning and night. This study found that children who lived with birth parents showed low levels of cortisol in the morning, but higher levels at night, and the opposite trend was observed for children living with foster care families (Bernard et al., 2010). These findings could mean that children living with foster families are initially anxious due to the transition, but the calmer environment lowers that anxiety. Children that stay within the birth family home may have lower levels in the morning because they are in a familiar environment, but face a more stressful day, and Bernard et al. concluded that the stress of a transition into a foster family can outweigh the stress of staying in a neglectful or abusive family.

There are a myriad of issues with the foster care system, and unfortunately there is never a single solution to fix it all. One problem that social workers can try to mitigate, though, is the loyalty conflict children face by reading the literature and understanding what aspects of the transition children struggle with the most. Checking in with children’s well-being, feeling of belonging within the new family, and asking if the birth parental visits are helpful or hurtful, are actions that could make the transition smooth and put the child at ease within a new family.

Word count: 1,093

0 notes

Text

Families in Poverty - Abigail R.

Intro:

Poverty is a disease that has plagued many Americans without true acknowledgment from those of higher socioeconomic status or from the government itself. The government’s purpose is to help the country as a whole but instead it ignores those in need while assisting those in power to remain in power. There have been implementations of government issued assistance for those in need, but it always includes a hole in the system that allows those in poverty to slip through the cracks and fall back into the only lifestyle most of them have known. Families in poverty provide a higher sense of urgency due to the needs that are required for raising children. Along with the parent’s necessities for living, with the addition of one or more children this can continue to push the family lower and lower into poverty. Children in impoverished families are faced with an incredible amount of stress and expectations to break the cycle of generational poverty and most of these attempts end in failure. In this Zine I will address the ways in which the United States Government provides false promises of assistance to those in need and how the system creates generational poverty within the families it effects.

The Enforced Cycle:

Poverty is handed down from generation to generation in this vicious cycle that continues to be placed in the next child’s hands to break. This is the way in which America’s socioeconomic system is set up; it is designed to keep those in low socioeconomic status or poverty in the situation they are in. The government implements ways in which those with financial struggles may be assisted such as Food Stamps. These are made to help families with purchasing enough food for a month or, how the Arkansas Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) describes, “get the food they need for good health”. This program sounds like a good solution for those of low-income families but as you look at the requirements of this program you can find faults within the eligibility. The website states that to be eligible for the benefit program you must fall into one of the two of the following groups: “Those with a current bank balance (savings and checking combined) under $2,001, or Those with a current bank balance (savings and checking combined) under $3,001 who share their household with either: a person or persons age 60 and over or, a person with a disability (a child, your spouse, or yourself).” By setting a maximum amount money one can have in their account, this creates an internal conflict of what the correct actions are to take to survive within the broken system the government has established.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the average household size from 2015-2019 was 2.52. For the sake of this example, we will be rounding this number up to 3. Looking back to the SNAP webpage, there is a section where you select the amount of people who currently live in your household to determine your eligibility for the program based on your income. If we select the given average household size the Census Bureau provided, it shows that your annual household income (before taxes) must be below $28,548. With this in mind, we now look to the Living Wage Calculation for Arkansas, which provides the Living Wage, Poverty Wage and Minimum Wage for the state. The living wage for the average family of three are represented in these combinations of adults and children; one adult and two children is $34.85, two adults (one working) and one child is $27.15, and two adults (both working) and one child is $15.54. While all of these seem to become easier with the addition of each parent working, the minimum wage in Arkansas continues to be $10.00. This is significantly less than what is needed to have a living wage for families with one adult and two children and even with two parents working, this wage is less than what is needed for them to have a comfortable income for their family.

To look specifically at the family of one adult and two children, the required annual income for this family to remain out of low socioeconomic status or poverty is $72,484. Let’s say that SNAP takes care of the necessary food for each month, there are still many expenses that the adult must pay for including childcare, housing, transportation, etc. Housing itself for this family of three, on average, is $8,777 and transportation averages at $11.672. If the adult of this household decides to save money for bills for their current car or home or if they are attempting to save up to provide a better home or form of transportation for their family, if they exceed the set amount of $2,001 or $3,001, they lose eligibility for these benefits which sends them back into the cycle. Families find themselves afloat financially just for a moment until the government determines them to be financially stable enough to cut off their Food Stamps which was a large part of their ability to stay out of poverty.

The government gives this sense of hope for families struggling financially to climb out of low socioeconomic status just to send them back down once they have become comfortable. This leaves those in poverty working their hardest to get out of the situation they’ve found themselves in but with the fear of losing eligibility to keep the financial assistance by earning ‘too much’ money.

A Child’s Perspective:

Children born into poverty are shoved into the harsh realities of the world before most adults ever have to. Child poverty rates have fluctuated over the last decades but have remained relatively steady. In 2019, according to the Center of American Progress, 14.4 percent of all children under the age of 18 in the United States were living below the official poverty measure, about 6 percent of children were living in deep poverty, and one-quarter were living in poverty or at risk. This is measured with the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), which is the number of noncash benefits the government provides, including the SNAP program as described before. Considering the previous section, the measure of child poverty may be underestimated with the conditions that are implemented with the SNAP program that may be taken away even while a family is still impoverished. Children of color are disproportionately represented among children in poverty, for example, while 14 percent of the children in the United States are Black, they make up more than one-quarter of children living below the poverty line. This statistic is due to the discrimination of labor markets that work against consist of racism, sexism, ableism, etc. The failings of the structural stability of the workforce remains unacknowledged while the promotion of the idea that poverty is the result of personal and cultural issues continues to be the reason people accept to be the true issue in America.

An article from the National Public Radio that was aired in 2014 provides the perspective of a teen and how poverty has influenced how he takes on challenges he is faced with. At the time of airing, Jairo Gomez was 17 years old and living in a one-bedroom apartment in New York City with eight other family members. Jairo is constantly faced with media and other forms of information reinforcing how unlikely it is for him to make it out of the cycle of familial poverty. Beginning high school, he still did not fully realize the financial circumstances he was under regardless of the state of his worn-down clothes. As someone who has grown up in poverty, I believe it to be a universal experience for a child living in such circumstances to not fully understand the extent of the situation until it is time for them to start making a life for themselves and planning for the future. Jairo was not always able to put his full attention into getting an education because he had to help his mother around the house and take care of his siblings while his mother worked endlessly to provide food and housing for them. He expresses his anger with others being born into wealthy families while he watches his mother work incredibly hard for them to never break out of this constant struggle to just get by. As many children in impoverished families do, they hope to be the one that breaks out of the cycle and be able to make a better life for themselves and future generations. Jairo expresses this dream but also takes into account the reality of the situation with dealing with college expenses. He realizes that he either must save for his own place out of the cramped apartment he is currently living in or for college where he can create a financially stable life for himself. The article ends with Jairo stating, “We’re told, ‘If you work hard, you’ll get results.’ But for my family, there haven’t been any results – just survival. (Jairo Gomez, 2017)”, which I believe summarizes America’s understanding of families in poverty.

Conclusion:

American families are constantly given this false image of hope through affirmations of the American dream or government ‘help’ that is promoted to provide families with financial help to further their work towards the American dream. As someone who has experienced this way of living first-hand, the amount of pressure put on the adults of the family to provide a financially stable household without the assistance of outside sources directly effects the children of the family. A child witnessing their parental figure’s struggles with money can create a sort of drive within them to gain success and someday find financial stability, but others fall into the habits their parents do. Whether these habits consist of inability to understand the virtue of saving money, resorting to drugs or alcohol as a form of coping or just an overall lack of hope of getting out of these financial struggles, they all enforce the cycle that low-income families face from generation to generation. Low-income and impoverished families seem to be acknowledged and taken care of by the American Government but if these forms of assistance actually did what they are promoted to do, there would not continue to be a steady percentage of Americans facing these financial struggles every year.

Word Count: 1,721

0 notes

Text

Marginalized Children in the Face of a Broken Adoption System - Greer A.

Throughout the history of the United States, marginalized communities have faced the brunt of racial discrimination and prejudice culturally, socially, economically, and politically. An important factor that has contributed to systemic racism throughout the course of the United States is the adoption process. Historically, adoption law has made it extremely difficult for children of color to be adopted by white people and for people of color to adopt white children. This dynamic created by our racist government has set back the foster care and adoption system decades.

The adoption process today is long and expensive and makes it difficult for those who struggle financially to engage in adoption. The process of adoption begins with a legal consent from the birthparents to relinquish their child for adoption (Adoption Center). After all legal and agency requirements have been met, a second consent to adoption must be granted to allow the adoptive family to finalize the adoption (Adoption Center). In most states, a consent from the child is needed. (Adoption Center). Finally, in a court hearing, an attorney representing the adoptive family presents the case and files for an adoption decree in which they can now become the legal guardians of the child (Adoption Center). A second finalization hearing occurs where the judge can ask final questions to the adoptive family, the child, the attorney, and the social worker (Adoption Center). This is to ensure the child is being placed in a safe and loving home. This seems straight forward, right? Maybe for the average white adoptive couple. However, this is far from true for parents of color.

Every year, about 135,000 children are adopted in the United States. Excluding adoptions by stepparents, 59% of adoptive children come from the welfare or foster care system (Adoption Network). 26% of children who are adopted from the United States are from other countries, and 15% of them are voluntarily relinquished (Adoption Network). It is important to note that 62% of children who are adopted are adopted within one month of their birth (Adoption Network). The majority of children who are adopted are babies, showing that older children are less likely to be adopted and are most likely seen as less desirable. How does race play a role into these statistics? According to the Adoption Network, 73% of adoptive parents are white, 40% of adopted children, “are of a different race, culture, or ethnicity than both of their adoptive parents” (Adoption Network).

The history of adoption places a deep-seated role in adoption policies and law today, greatly due to the presence of racism in the United states for centuries. In the work of Sarah Trembanis, A Darker Hue: Race and Adoption in Richmond, VA, Trembanis outlines the racially charged adoptive process. A Darker Hue seeks to examine how the issues of race and colorism intersect with African American adoptions and state policies during the 1950s and 1960s. The era of Jim Crow laws greatly impacted state policies in regard to laws surrounding the family. For instance, anti-miscenegation laws were common across the country. These laws banned relationships between men and women of different races and would not recognize them as legitimate marriages. Due to anti-miscenegation laws, these families could not be adoptive parents. In addition, religion was many times used as a guise for racism in law. In the state of Virginia, a judge refused to approve the adoption of a blue eyed and blonde hair child to Black parents. However, the reasoning for this was that this decision would protect the children’s inborn Catholicism (Trembanis 2017, p. 8). Trembanis (2017) discusses the “problem of the brown baby” as a public policy as early as the 1940s. Historically, few adoptive homes and orphanages were willing to take children or babies of African American or mixed racial descent. This was due to a variety of reasons. Trembanis argues that this was due to a lack of public funding or agencies that would take on black children, racial prejudice among a majority of white social workers, and a history of informal kin adoptions (Trembanis 2017, pp. 6-8). She also argues that there was a justified concern by African American adoptive families that social workers and the state would judge their families, lifestyles, and homes and would be unwilling to grant a legal adoption.

In 1959, in the state of Virginia, the infamous contested adoption case of David Alexander Rowe came to a head. David was born to a fourteen-year-old African American girl, Georgia Mae, who was working as a prostitute when she was impregnated by a twenty seven-year-old white father of two. Georgia Mae was arrested for prostitution and taken to jail while her white counterpart did not face any charges for eliciting sex from a minor. During her arrest, no family members were contacted despite her status as a minor. David’s mother was confined to an all-girls home until her eighteenth birthday after being released from prison. She requested that David be adopted by her aunt. This request seemed to be noncontroversial as the mother wanted him to go to a family member. However, the Virginia Department of Welfare denied this adoption as David was “too fair” to be adopted by a dark-skinned family member despite the aunt passing all home inspection and requirements.

While there has been an improvement in the policy and law-making surrounding trans-racial and cultural adoption, there are still many things to be improved. Katherine Sweeney organized and facilitated 15 in-depth interviews with white parents who were willing to adopt children in her pursuit in understanding how race plays a role in adoption choices. She found that parents who were willing to adopt children of color stressed an unwillingness to adopt Black children (Sweeney 2013, p. 44). There is a clear discrepancy between the available adoptive children and the willingness of White adopters to adopt children of color, particularly Black children (Sweeney 2013, p. 44). Racial classification plays an important role in this as well since multiracial children are classified separately from Black children as if multiracial children would not experience racism. Children who are waiting to be adopted are listed with their race, so adoptive parents are making choices based on race whether not it is a conscious thought process or not. White children, specifically infants are at the top of the hierarchy in adoption preference and are typically more expensive to adopt as they are usually adopted through private domestic adoption agencies (Sweeney 2013, p. 48).

Race and racial discrimination are prevalent in adoption and has been for a long time. Systematically, the welfare and child protective services system continually fail children of color, leaving them stuck in a hurting and broken foster care system. The legality behind the adoption process makes it difficult for children of color to break through the oppressive foster care system. As we move forward as a nation, we must not forget about some of the most vulnerable and marginalized people in our country, our children. Creating racially conscious legislation and dialogue will enable us to benefit children of color instead of favoring a system that seeks to benefit the rich, white, and powerful.

Word Count: 1184

1 note

·

View note

Text

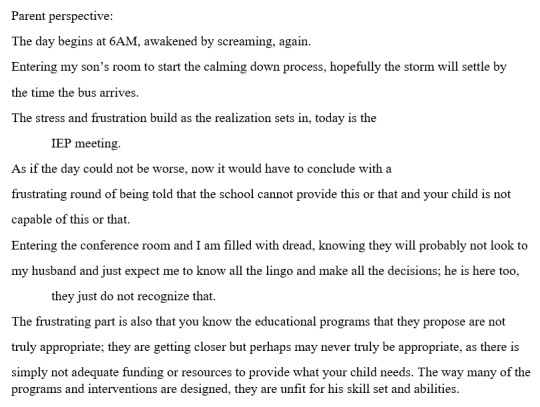

Families with children with Disabilities: U.S. Education System - Abby N.

American social programs and systems have good intentions, but they often fail to truly provide adequate services to families in need. The families in our zine have experienced hardships as a result of these inadequate systems. Consequently, just as other marginalized families, such as those in poverty or those with adopted members experience adversity, families that have a member with a disability face a host of challenges that other families cannot imagine. These struggles often go unnoticed, but they nevertheless have a great impact on the lives of many families.

Families that have a member that has a disability face particular challenges within the U.S. education system. These experiences are especially important as Glenn Fujiura contends that, “…families with disabilities represent a significant proportion of today's families.” (Farrell & Krahn, 2014, p. 2). Thus, a large portion of families today include members with disabilities and therefore may face these struggles. Farrell and Krahn (2014) concluded that families with a member with a disability are diverse, resilient, face stress, and often have issues getting proper support (1). Some specific struggles that these families face are a lack of appropriate education and communication with educational professionals and a lack of an inclusive education. Additionally, Farrell and Krahn make the point that poverty is more common among families with disabilities than in the general population (3). This indicates that poverty should also be discussed within the context of families with disabilities. Therefore, since families with members with a disability make up a significant portion of the population, and they are facing struggles that are often exacerbated by poverty, we should seek to learn more about the hardships of these families. We should also seek to change policies to ensure that these families receive the support they need.

A big part of the problem of the lack of appropriate education and communication with educators stems from the structure and format of the Individualized Education Plan or IEP process. In the article, “Fathers’ Experiences With the Special Education System...,” Mueller and Buckley address how overall the IEP process is poorly designed and very difficult for parents of children with disabilities. At an IEP meeting, the parents, or guardians of the student with a disability meet with the school personnel to discuss the child’s educational plan, including their extra interventions and goals. These meetings are often a source of great stress for these families (speaking from personal experience as well). There is often a power difference between the parents and educators, as the educators tend to use lots of educational jargon that the parents do not understand. This makes communication between parents and educators difficult which makes it challenging for parents to advocate for their child’s needs (Mueller & Buckley, 2014, p. 120). The authors specifically review the experiences of fathers when dealing with IEP meetings, as fathers’ experiences are not usually talked about. The authors discovered that the fathers faced many issues regarding the IEP meeting itself and with collaborating with the educators (Mueller & Buckley, 2014, p. 124). The fathers found the meeting itself overwhelming, unwelcoming, uncomfortable due to the use of fancy jargon and requirement of an extensive knowledge of laws and rights. The fathers also found the IEP meeting to be insufficient in that it was not efficient or productive, and there was no agenda or structure (Mueller & Buckley, 2014, p. 124-125). Regarding the collaboration issues, the fathers also felt unheard and as though they were fighting a battle with the school district to advocate for their child’s needs. They wanted to be able to work together to come up with a resolution (Mueller & Buckley, 2014, p. 126-128). Therefore, the disconnect between the fathers and the educators in the IEP meeting causes communication difficulties. This translates into the child not being provided the appropriate services, as the parents are unable to effectively advocate for what their child needs.

Additionally, the fathers felt especially left out of the meeting given their apparent role in the family and in the child’s life, as the father is assumed to be more of a playmate. Since our society assigns this role to fathers, they are often left out of educational decisions and the school professionals look to the mothers for input regarding the child’s educational plan (Mueller & Buckley, 2014, p. 121). This is similar to the discussion in our class of gendered family roles, where men are expected to be the breadwinners and the females the child caretakers (Class Notes 2/16). This conception of gender roles keeps the fathers from being truly included in the educational process. Consequently, to provide the best care and educational experience for the child, we need to overcome these social norms and seek to include both parents/guardians equally in the conversation about the child’s services.

“There’s so many different abbreviations for this and that, sometimes it, it’s overwhelming. Maybe try to get the fathers to participate a little bit more. Try to draw them in . . . maybe remember that when you’re talking in IEP language, that not everyone at the table understands what all the abbreviations mean.” (From one of the fathers from Mueller and Buckley’s study, 2014, p. 125)

What can we do about these problems?

The authors also suggest many policy changes that our society could put in place to support families with children with disabilities, specifically in the IEP process. These include trying to ensure that both parents or guardians are equally participating and involved in making decisions about their child’s care. They also propose that there should be policies to make IEP meetings more productive and fit parents’ knowledge and skill set better. (Mueller & Buckley, 2014, p. 129-130). Similarly, the Center for Parent Information and Resources also provides some suggestions for how to make the IEP process better and the schools more accommodating to students and parents. First, schools should provide parents with appropriate information about the process. Parents need to clearly understand what their child is entitled to in the IEP process and what that process looks like before having to advocate for their child’s educational services. Some policy changes could be a course that educates parents on the process and what their child is entitled to, presented in a way that the parents understand (Center for parent information and resources, 2021). These policy changes could address some of the communication difficulties faced by these parents, improving the quality of education that their child receives.

Another key struggle that families with children with disabilities face specifically within the U.S. Education system is receiving an inclusive and appropriate education. Under the IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act), all children are entitled to a free and appropriate education. Yet, many parents face the decision of whether to move to get their child in an appropriate school or to take the school system to court and fight it (Kluth et. al., 2007, p. 43). This should not be a decision that parents have to make. The schools should be inclusive and provide appropriate services, as is mandated by the law. This situation can have implications in our class discussion of parenting and social class. This is in how parents will do anything for their child, like go to extreme lengths to provide diapers for their child, just as these parents were willing to move to provide their child with an inclusive education (Class Notes 2/18/21).

Kluth et al. (2007) interviewed twelve families of children with severe disabilities who decided to move to get their child placed in an inclusive school. The authors of the article addressed the parents’ reasons for moving, which included concerns about their child being accepted at the school or schools being resistant to being inclusive. In addressing concerns about being wanted at the school, many parents expressed that they did not feel as though their child was welcome at the school. One parent was practically told “why don’t you go somewhere else�� (48). These parents shared how they just wanted a school that wanted and accepted their child and was willing to make the school fit their needs. This is articulated by the quote, “All I want is a school that wants my daughter. That’s it.” (48). The parents also discussed how inappropriate the curriculum was in that it only focused on behavior issues or functional skills and not academic or age-appropriate curriculum that fit the child’s skills set. Parents also faced resistance from the school in being inclusive, where the school simply told them they do not provide an inclusive education or that they did not have the supports to do so (47). These concerns all indicate the problems within the school systems that should be addressed. Overall, all these concerns often result in parents deciding to move to get their child placed in a more inclusive school environment, which can cause a lot of financial and emotional strain on a family.

I said, “Where is the special education teacher?...” The principal said, “Oh no, when you chose this school, instead of the [segregated] placement that you were offered, you gave that up. You gave up having a special education teacher.” (Colleen, a parent described in Kluth et. Al's study, 2007, p. 48).

“I mean, everything within me wanted to stay there and fight. Everything! I think that is just myself and who I am. I think we owe it to the next person to try and make it easier.… the fact that the teachers don’t want that child there. It’s very obvious. Your child is not going to be able to learn in that environment.” (Darcy, a parent described in Kluth et. Al's study, 2007, p. 49).

Finally, the authors mentioned many possibilities for policy changes or guidelines that schools should follow to promote inclusive educations. Some of these suggestions included making inclusive schooling viewed as a “process and as an action.” This entails having schools take an active approach to promoting an inclusive education and an attitude of true acceptance of the child (Kluth et. al., 2007, p. 53). Another suggestion was that the schools must have “strong and visionary leaders” who will promote inclusive schooling and adjust their teaching style to fit the needs of the students (54). Some policy changes within the education system that the Arc is pushing for include encouraging the government to fully fund educational services for children with disabilities, not just part of it. Currently the government is leaving it up to the states to handle which results in insufficient funds. They also support families in ensuring that the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) is upheld, and its premises followed (The Arc, 2020). Overall, there needs to be changes in how our schools are run and funded, so that parents are not forced to make the difficult decision of moving to give their child a better educational experience. It is up to future educational professionals to promote this type of learning, where the students’ educational needs can be met, and they feel welcome and accepted for who they are.

In connecting these educational issues with issues of poverty, in an article describing the impact of poverty on the lives of families of children with disabilities, the authors (Enwefa, Jennings, 2006) discuss how 28% of children with disabilities aged 3 to 21 are living in families in poverty (3). Poverty and all the difficulties that come with it is extremely stressful on families that have children with disabilities; so much so that it even hurts the children’s ability to succeed in school (1). Poverty puts a huge strain on the parents, who face difficulties focusing and managing their child’s educational needs when they are struggling just to provide for their daily needs (7). Some of the specific stressors that these parents deal with are a lack of a social service system, education, healthcare, and employment (4). These are extremely detrimental to these families, as they are not only trying to deal with all the challenges that come with living in poverty, but also caring for a child with needs that surpass that of a typical child. The authors discuss how to support these families, there needs to be more awareness of their experiences. The community should also create a support system to assist the families (13, 15, 19). Overall, communities need to come together to evaluate how their current systems are not helping but are hurting these families and how everyone can work together to help each other (25).

Often the experiences and struggles of families with children with disabilities go unnoticed by many in our society. I think this is because a stigma exists around disabilities in general. This is also because children with disabilities and their families are different and our society shies away from discussing or associating with anything that is deemed “different.” People in our society are often left uncomfortable by people with disabilities. I feel as though this usually stems from a place of ignorance and the fact that we do not like things we do not understand. Thus, to begin to understand those with disabilities and their families, we must start listening to them and their experiences. This not only applies to these families, but all families of marginalized groups discussed in this zine.

The brokenness of our U.S. education system needs to be addressed and that can start by listening to the experiences of these families and acting on it. Children with disabilities and their families need voices and to be heard so that this stigma can disappear, and people can start to support these families. This support can go a long way in advocating for the improvement of our education system. This can start with you, you can first be willing to listen. Then you can take what you have heard and use it to positively impact those around you, by being empathetic and kind to those with disabilities and their families. This message of being understanding and willing to listen applies to all the marginalized groups previously discussed. All these families should receive support and encouragement from others, so that they can have their voices heard.

Word Count: 2,155

0 notes

Text

Zine Bibliography

Adoption Center. P. (n.d.). Adoption laws. Retrieved April 17, 2021, from http://www.adopt.org/adoption-laws

Bernard, K., Butzin-Dozier, Z., Rittenhouse, J., & Dozier, M. (2010). Cortisol production patterns in young children living with birth parents vs children placed in foster care following involvement of child protective services. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164(5). doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.54

Biehal, N. (2012). A sense of belonging: Meanings of family and home in long-term foster care. British Journal of Social Work, 44(4), 955-971. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcs177

Center for Parent Information and Resources. (2021) What Is the CPIR? Center for Parent Information and Resources. https://www.parentcenterhub.org/whatiscpir/

Dansey, D., John, M., & Shbero, D. (2018). How children in foster care engage with loyalty conflict: Presenting a model of processes informing loyalty. Adoption & Fostering, 42(4), 354-368. doi:10.1177/0308575918798767

Enwefa, R. L., Enwefa, S. C., & Jennings, R. (2006). Special Education: Examining the impact of poverty on the quality of life of families of children with disabilities. The Forum on Public Policy, 2006(1), 1-27. http://www.forumonpublicpolicy.com

Farrell, A. F. & Krahn, G. L. (2014). Family Life Goes On: Disability in Contemporary Families. Family Relations, 63(1), 1-6.

Fawley-King, K., Trask, E. V., Zhang, J., & Aarons, G. A. (2017). The impact of changing neighborhoods, switching schools, and experiencing relationship disruption on children’s adjustment to a new placement in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 141-150. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.016

Fossum, S., Vis, S. A., & Holtan, A. (2018). Do frequency of visits with birth parents impact children’s mental health and parental stress in stable foster care settings. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1429350. doi:10.1080/23311908.2018.1429350

Glasmeier, A. K. (2021). Living wage calculator. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://livingwage.mit.edu/states/05

Haider, A. (2020). The Basic Facts About Children in Poverty. Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress.

Kluth, P., Biklen, D., English-Sand, P., & Smukler, D. (2007). Going Away to School: Stories of Families Who Move to Seek Inclusive Educational Experiences for Their Children With Disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 18(1), 43-56.

Maaskant, A. M., Van Rooij, F. B., Bos, H. M., & Hermanns, J. M. (2015). The wellbeing of foster children and their relationship with foster parents and biological parents: A child’s perspective. Journal of Social Work Practice, 30(4), 379-395. doi:10.1080/02650533.2015.1092952

Mueller, T. G. & Buckley, P. C. (2014), Fathers' Experiences With the Special Education System: The Overlooked Voice. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 39(2), 119-135. DOI: 10.1177/1540796914544548

Stein, C. (2014) 7 kids, 1 Apartment: What poverty means to this teen (1202092942 897117210 K. Pitkin, Ed.). Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2014/11/18/364062673/new-york-city-teen-balances-school-and-life-in-poverty

Sweeney, K. (2013). Race-Conscious Adoption Choices, Multiraciality, and Color-blind Racial Ideology. Family Relations, 62(1), 42-57. Retrieved February 16, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org.hendrix.idm.oclc.org/stable/23326025

The Arc. (2020). About Us. The Arc. https://thearc.org/about-us/

Trembanis, S. (2017). “A Darker Hue”: Race and Adoption in Richmond, Virginia, 1959.

Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 5(1), 3-26.

doi:10.5406/womgenfamcol.5.1.0003

US adoption statistics: Adoption Network: Adoption Network. (2021, March 10). Retrieved April 17, 2021, from https://adoptionnetwork.com/adoption-myths-facts/domestic-us-statistics.

U.S. census bureau QUICKFACTS: United States. (n.d.). Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

Welcome to benefits.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.benefits.gov/benefit/1108

0 notes