Photo

Here’s what I’m learning, working as a photographer and writer, and publishing my photographs and stories in the communities in which they are made: People want to be respected. They want fairness. They want for themselves and their communities to be seen.

The problem is, it is nearly impossible for any group of people to agree on what that means. I have found that one person may see a photograph or read a story and experience it as beautiful, aspirational, even transcendent. Another person may see the same photo and story and view them as outrageous, harmful, disrespectful. In the end, I hope that these clashes of perspective might lead to a finding of commonality, to an appreciation for others’ views, and to respectful dialogue and conversation.

My work in Georgia is a work in progress, with a public installation as the final goal. There is much more to be done, and I have much more to learn. I have come to love the people I have photographed. To try to be the most fair to them all, as I express what I see, I’ve decided it will be best to publish the photographs and stories all together, when the body of work is complete.

I hope you will stay tuned! Thank you to all,

Mary Beth

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It was the day of the senior prom in Newnan, Georgia, and it was hot – unseasonably hot, I was told, for the South. I had been running around all afternoon when I received a text that the downtown was full of young men and women in their tuxes and gowns. As I headed there, I crossed the train tracks, where a girl in a long red dress was posing for a picture. I stopped at the city park, which was fluttering with teenagers as though they were butterflies, in brilliant raiment of magenta, azure, peach, gold . . .

I got out of the car and started photographing couples: girls holding balloons with elaborate hairdos piled on their heads, boys standing tall with lots of promise in their stiff clothes. Nothing I made felt good to me. Plus, it was so hot!

Just as I was about to leave I saw a woman using her cell phone to photograph a couple. Her blond-streaked hair was catching the light, and her jewelry sparkled from feet away. I approached her, asked if I could make a few pictures of her. She said yes and told me her name was Teneka, and that her two small daughters were with her. While the girls circled around us, we made a few frames. Then I left.

When I later looked at the photographs of Teneka, they – like so much of the work I’d done that day – disappointed me; they didn’t feel the way I had felt when I had first seen her. But then there was one photograph that I didn’t remember taking, in which the wind had lifted her hair, and she seemed for a moment to depart to another place. I decided to make a print, and to call her.

When I reached Teneka by phone, she told me that she was working – she goes to people’s homes, doing their hair and makeup – in a neighborhood north of town. She said she’d have a lunch break in the afternoon, and that we could meet then. She gave me an address, and when I arrived, she was sitting in her car, waiting for me.

Inside Teneka’s car, the air was cool and scented by the spicy wings she’d picked up for lunch. When I pulled out her portrait and gave it to her, she stayed silent for a second. Then she said, slowly, “Oh my God, oh my God,” and started to cry. Then I started to cry, and we just sat there for a while.

“It’s like I’m saying, ‘God, just take the wheel,’” she finally said. “‘Just give me the faith that I need, that strong independence. Just help me move on to my next destination.’”

Teneka told me all about her two daughters, ages 6 and 9, and her father, whom she’s caring for, who has early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. She told me that she loves having her own business, but that the strains and frustrations have grown increasingly trying. She said that when I met her she’d been photographing a client she’d been with all day.

“I’m a total believer, and I’ve been praying a lot,” Teneka continued. “Like, I don’t know, sometimes you wake up with a lot of demons, or a lot of weight on your back. And you know, you just gotta talk to yourself, and faith is what you need. I got to keep moving. I got to keep going, no matter what goes on in my life.”

I asked her what she thought her photograph said about her. “It says I’m humble,” she said.

"I’m God-fearing. I’m a hard worker. I love.”

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

While working in Georgia, I am trying to consider the long threads of history: how they come together to weave the present moment, tethering the present to the past. If I’m to make work that helps people see past their bubbles into the lives of another, mustn’t I look backward, to see how these bubbles were created?

In Newnan, black and white people have lived side by side – and in almost equal numbers – since its founding, in the early 1800s. At that time, Scotch-Irish and English settlers moved inland from the coast, bringing their families, their animals, and their slaves. Many built cotton plantations and immense fortunes – soon turned to dust by the Civil War. In the following decades, poor white farmers and freed black slaves, both now tied to the land as sharecroppers, would replant the cotton and bring it to harvest. The landowners, with their newly built textile mills, would turn that crop into a dazzling wealth. By 1910, a local newspaper reported that Newnan was the fourth-wealthiest town per capita in the United States.

I’ve noticed that with many white people in Newnan, talk of the power structure that underpinned the town’s beginnings is met with hushed tones, or outright resistance. What does that have to do with today?, I’m sometimes asked. What is the cutoff date, beyond which we don’t have to talk about this anymore? But with members of the black community, talk of those times rises quickly to the surface. Speaking of his ancestors’ contribution to the town’s white ruling class, one black man told me, “I earned that money for them, and I didn’t get anything.”

So in thinking about Newnan’s founders, I wondered where I might meet their descendants today. I was told they attend Central Baptist Church.

On the Sunday that I visited the church, Barbara caught my eye. She was petite and trim, with a bright blond bob and a rosy-pink jacket. She looked the way I’d imagined a Southern woman would look, and I asked to be introduced to her. I told her about my project, and asked if she’d be willing to let me make her portrait. She laughed, and agreed to let me call her later that week. I asked if she would wear the same pink jacket.

Barbara told me that she’d moved a log cabin onto her parents’ property, but when I arrived at the address I found myself in front of a white house. I called Barbara on her cell phone, and she told me that I was at her parents’ house, but that she’d come to get me. While I waited I looked around – at the vast woods, the flower garden, the American-eagle ornaments everywhere. I couldn’t help noticing a small statue, situated on one of the house’s front steps. It portrayed a black child seated with his ankles crossed, holding an American flag. It shocked me.

Barbara arrived, and we sat down on those steps. She told me about herself – that she’d been a flight attendant for Delta, that she competed in triathlons, that she had two grown children. She had just moved back home, to be near her family, after living in Atlanta for two decades. She told me that her parents’ house had been built before the Civil War, and that the land had been in her father’s family since the early 1800s. She said that her mother’s family had been in the cotton-gin business.

When I asked if I could make Barbara’s portrait there, as she sat on those steps, she chafed a little. She put her hand on the statue and said, “Doesn’t this offend you, sort of, a little? I mean it’s kind of cute, but can you imagine some black person walking up and seeing that? If I had a friend of mine who’s black come here,” she went on, “I just don’t think they’d appreciate their race sitting on the steps. They’re portrayed as being a slave, like ‘the good old days.’ I just don’t know about Little Black Sambo out here. It’s not nice.”

For the next hour Barbara and I talked about this portrayal. She told me about Elvo, her family's African-American maid, whom she had loved growing up, and her grandmother's beloved chauffeur, who once drove a birthday cake all the way up to Barbara in Atlanta. “They were not viewed as anything different,” said Barbara. I wondered if she meant that they weren’t viewed as unequal.

“But they were, kind of like, in their place, though,” I said.

“That’s what their place was, yeah. That’s how we viewed 'em, as just kind of helping.”

“The help,” I said.

“Yeah, there you go,” she said. “The Help. Driving Miss Daisy.”

I could tell Barbara didn’t want to criticize her parents, yet she talked of their views as both generational and persistent. I asked her to name a stereotype of black people that she’d often heard. “Lazy,” she said quickly, and added, “When I lived in Atlanta, you know, you just see a black guy walking with his pants half down and you’re scared to death. I am. I don’t know why.”

Then she told me a story about a running group she had belonged to, which worked out with homeless men, most of whom were black. Three times a week she rose at dawn, picked up the men in her car, and took them on long runs. They charted one another's progress, and competed in races. “It’s amazing how you get to know someone like that,” she said. “I mean, you encourage them to come work out, and they become your best friends. And oh my God, it was just a rude awakening. It will be a lifetime experience I’ll have forever. It was wonderful.”

When we were finished making photographs, Barbara and I agreed that we’d meet again before I left town. I admired her honesty, and in the following days I imagined her as somehow wedged between a generation compelled to portray a black person in humiliating caricature – a childlike object on a step – and a generation to which people of color might appear as equals.

I showed Barbara's portrait to a few people – including a friend of mine, who is black, who said, “She let you set her up like that?,” and Barbara’s mother, who said, breezily, “Oh I love that you’ve got the little black man in there!” When I showed it to Barbara, she gasped at her appearance, making a joke about needing plastic surgery. But then she said, “I love it.

“I love the picture because I think it speaks about the way our country is so divided right now. It speaks about the controversy between the blacks and the whites. . . . You have the Southern house – the Antebellum house – and the Little Black Sambo holding the American flag. And then you’ve got the eagle, which is the symbol of our country. And you’ve got the white supremacy.”

“Barbara,” I said, “this picture puts you in the position of the white supremacy.”

“That’s what I’m saying,” she said. “It puts me in the position of the white supremacy. I don’t like that. But that’s how it is.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

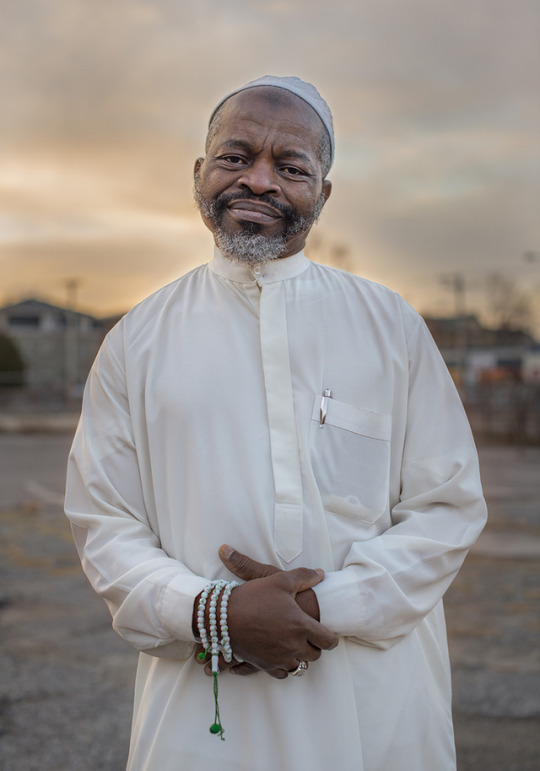

When I first met Imam Alli-Owe, he was wearing a kelly-green T-shirt over a white prayer robe. Bold white letters on the front of the shirt spelled: Your Friendly MUSLIM Neighbor. On the back of the shirt was written: Islam for PEACE.

This was during the 2016 presidential campaign, when anti-Muslim rhetoric had begun to grow, the violent acts of a few becoming confused with the beliefs of many. The Masjid Al-Kareem, a mosque on Providence's Broad Street, was holding an open house to educate its neighbors in their understanding of Islam.

I was struck by how little I knew about Islam, how foreign and remote the religion seemed, despite the decades I’d been working with cultures other than my own. I began visiting the mosque on Fridays for midday Jumu'ah prayer, when the low white building was filled with hundreds of worshipers. I was surprised at how, in this both foreign and familiar setting, the images of young Muslim men as terrorists had seeped into my consciousness.

Yet here were all these friendly people in their green T-shirts! As the white-robed man scurried around, arranging chairs and putting out refreshments, I met people from Somalia, Ghana, Pakistan. I met Providence-born people of Cape Verdean descent, and a woman who traces her roots to the Mayflower.

I introduced myself to the man, who told me his name was Imam Alli-Owe – Imam Alli for short, the title Imam a reference to his position as a leader in the Muslim community. He was open to being photographed, and we agreed to meet on the coming Saturday at the mosque. He told me he would be there for the first daily prayer, before sunrise.

It was still dark when I got to the mosque that morning, but as the prayer ended and people streamed outside, the sky began to lighten. Imam Alli approached me, wearing his prayer robe and beads wrapped around his wrist. We made some photographs behind the mosque, in the pearly moments between night and day.

I didn’t see him again until almost a year later. This time it was at a different mosque, the Masjid el Rassaq, also on Broad Street; it had been started by Imam Alli and others to serve the specific needs of the Muslim community from Nigeria, Imam Alli's native country. This time he was dressed in a robe of blue and gold, and was headed to a wedding. He said we could talk at the mosque the next day, after sunrise prayer.

When I arrived the next morning, a bright moon shone in the sky, and Imam Alli was still wearing his clothes from the night before. He told me that after the wedding he’d returned to the mosque at about one a.m. and, rather than go to sleep, he decided to stay awake, and pray. I asked him what he’d been praying for.

“We pray for the blessings of Allah. We pray for the world – for peace in this world. There’s no peace in this world. Everywhere there is killing – we don’t love each other, and that is against God.”

I asked him what he thought was the very worst thing going on in the world. “The worst is that we don’t love each other,” he said. “We don’t love ourselves. Everybody is lost.

“We are all – we all came from the same father and the same mother! We are all from Adam and Eve! So Allah created us – but we don’t love each other because of power. We want to have power. So many – they don’t believe in God, but they believe in money. They believe in dollars.”

Imam Alli continued, “This ISIS – they are killing innocent people! That is not Islam! Killing people is not Islam.” Then he repeated, almost to himself, “That is not Islam.”

Imam Alli insisted that a central rule of Islam is to love one’s neighbor. His words rang deep, and so much at odds with the fear of Muslims as terrorists – impossible to reconcile with the words of the U.S. president, who has convinced so many Americans that Muslims are their enemies.

With these thoughts, I asked him if Love your neighbor applies only if one’s neighbor is Muslim.

“Your neighbor!,” he said, almost scolding me. “It doesn’t matter! Your neighbor might be Muslim, might not. But your neighbor is your family.

“For instance, we came here. We have our family back in Africa, but we live here now. If you’re living beside me, if anything happens, you will be the first person to reach me.

“Do you understand me?” said Imam Alli. “You are my family!”

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

What is it that I should tell you? Should I describe the way the bombs sounded, or name the friends and neighbors killed? Should I list what she packed in her meager bag as she walked away from her home, her family business, her life? Should I use the word refugee, and summon up all that that word conjures?

Here is Bidur – a photograph of Bidur. She is 27 years old. We made it on a freezing cold afternoon, outside the apartment where she now lives, in Providence. She and her family are among the eleven million – eleven million – who’ve lost their homes during six years of war in Syria. Some 18,000 of these people have made it to the United States; fewer than 200 of them have made it to Rhode Island.

When Bidur, her husband, Hussein, and their three children arrived in Rhode Island, in February of 2016, a cheerful committee met them at the airport, holding welcome signs, written in Arabic. The greeters were members of Rhode Island’s Muslim and interfaith communities, and representatives of Dorcas International Institute and the Refugee Dream Center, which settle new arrivals. Bidur says she thought she’d be safe in Providence, able to forget everything about the war. But then rats scurried through the apartment into which she and her family had moved, and a burglar broke in and stole the TV they’d been given, and Bidur started to feel afraid again.

Now in a clean, bright apartment above a restaurant, she tries not to be alone, but always to have her husband or children with her. She looks forward to the summer, when her windows will be open and she’ll be able to enjoy the sounds of the diners on the restaurant patio below, laughing and singing and playing music.

I want you to know that when a visitor arrives at Bidur’s apartment, her children approach the door, pointing their chins upward to kiss the stranger’s cheek. Bidur and Hussein do the same, and then she disappears, returning with a tray of dark coffee in tiny cups, dried dates, and sweet cake dusted with pistachios and scented with rosewater. I also want you to know that her children were examined by doctors and she and Hussein answered more than 16 hours of questions – Have you ever been in prison? Have you ever owned a gun? Have you ever killed someone? … – before being allowed to enter this country.

I want to tell you that Bidur misses the electric appliances she had in Syria, that she grabs her baby and kisses him with relish, that she disagrees with at least half of what her husband says. She is feisty, funny, quick. She wants to learn English (endearingly, she sometimes says “You’re welcome” when she means “Thank you”) and wants to learn how to drive. She hopes her husband, who in Syria had a pump manufacturing and repair business, can find a job: working with electricity, heaters, air conditioning – anything. She is grateful that her children are in school. That’s it – she doesn’t want anything else, except to be safe.

Bidur laughs a lot, even when telling the worst of her story. “Because everything is bad,” she says, in Arabic, “we have to laugh. If we cry we will not change anything.”

An English-speaking friend of Bidur’s, named Baraa, is here, translating for us. Baraa is also Syrian, having arrived in Providence with her family just six months ago. Often, while we all talk, Baraa weaves her own thoughts into her translations.

With Baraa’s help, I ask Bidur why she has agreed to be photographed, to have her image publicly displayed, at such a contentious time. She says something in Arabic and holds up her hands, lacing her fingers together. Baraa translates: “We should all be able to live together – Christian, Muslim, Jew." Baraa then says, “If I take off my hijab, or I take off my clothes, what is the change in me? My heart is my heart. Your heart is your heart . . . We love Jesus. We believe in Jesus. We believe in David, and we believe in Mohammed – we believe in all the messengers.”

We discuss the fact that many Americans don’t know this about Muslims – that they honor Jesus and are not enemies of Christianity. We acknowledge that it’s a dangerous time in the United States to be wearing a hijab, to look like “the other." We talk about the many Americans who are angry, protecting their turf – and how they are apt to confuse Islam with terrorism. We talk about ISIS.

“ISIS?” says Hussein, through Baraa. “They are crazy, like Trump. They are not Muslims. Muslims do not kill people, don’t do anything to make God angry at them.

“There are a lot of people like Trump,” Hussein continues. “A lot of things they think about Muslims – they think all of us are like ISIS, because they don’t know about us. When they see we are good people, they will respect us.”

Baraa considers his words, as she translates for him. Then she adds: “I don’t know if that will happen.”

Bidur, too, has a moment of hesitation – of worry – about putting her photograph out there. "What if someone tries to hurt my children?" she says. But then they all decide that that won’t happen, that all will be fine. They agree it will be as God wants it.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I first see D.J. along the route of the Veterans’ Day parade, in Newnan, Georgia. He’s sitting in a plastic folding chair patterned with the American flag, next to a woman seated in an identical chair. I’m rushing to get to a ceremony nearby, but I can’t help noticing his appearance: long graying beard, a black vest covered with pins: one for the Marine Corps, one for the U.S. flag, one for the Confederate flag.

When I look at him, I think I know what I see. I think: Here’s the guy who will give me the white, redneck view of the South.

Quickly, I introduce myself. I tell him about my work, photographing people, and ask if I can visit him sometime. He tells me his name and number, and that he works at a local flea market. He gives me directions and says he’ll be there later that afternoon.

After lunch I drive out to the market, only a short distance from the center of Newnan, but the landscape becomes rural very quickly here. When I arrive I see D.J. in front of a little stall on the corner, fabricated out of corrugated metal and painted blue. I approach him and ask if he has time to talk. It’s been slow today, he says, and agrees to sit down with me. We drag two chairs over to the side of the stall.

I ask D.J. about the parade, and about his military service. He tells me he’s been in the Marine Corps, served in the latter part of the Vietnam War.

Wanting to get to the heart of the matter, I ask him who he supported for president.

“Hillary,” he says.

Surprised, I pause.

“I was raised by Democrats,” he says. “When I grew up, the Southern part of the country was Democrat – it switched to Republican probably in the '70s. So, when I was growing up, my parents and people, if they voted, they usually voted Democrat. But votin’ wasn’t a big deal back then. Everybody was too busy to vote. Most of my people were farmers, they were raising their own food. It’d be a long trip to town, too, to vote – in a beat-up wagon and mule, or my parents’ old pickup truck.”

I ask him about the Southern switch, from Democratic to Republican, which, as I understand it, had to do with the Democrats' having embraced civil rights. “It was mainly because of what I would call the Bible Belt beliefs,” D.J. says. “Anti-abortion, anti-gay – all the stuff, stuff like that. I don’t believe in abortion, but I believe women – what I say is, you can regulate laws, but you can’t regulate morals. You can’t make a law because you don’t like the way I believe. This is the way I think of it.”

I ask D.J. now what he thinks of Donald Trump. “To me, he acts to me like a high-school bully,” he says. “He’s rich, and he thinks he’s better than everybody else. . . .

“It’s pretty obvious that he is anti-anybody but white,” D.J. says. “White-collar rich people making over two hundred thousand dollars a year – that’s all he has anything to do with. He doesn’t have anything to do with people like me and you, or blacks or Muslims or Spanish people, Mexican people. He just don’t like nobody. He likes his self, a model for a wife, and his kids. That’s the only people he cares anything about. And I’m not so sure he cares about his kids.

“I think that his hot head gonna get us into the biggest war we’ve been in since World War Two.”

I can’t bring myself to confess my initial impression of D.J., but I tell him that if any old Northerner were to meet him, they might assume he was a white racist, who’d supported Trump.

“No, I’m not nowhere near racist,” he says. “I was in the service with a bunch of guys, and I judge – I try not to judge people, period. But if I judge you, it’s because I know you. It doesn’t have anything to do with your color, your race, or your creed, or your sex, or anything. I don’t even have a problem with Muslims. Southern guys, they don’t like the Muslims. And some old school Southern people have a problem with blacks, and people who don’t believe like they do. But I don’t have a problem with anybody.

“My experience is, times I’ve been up North and Midwest, they’re more racist than the South. They’re more segregated than we are – in the big cities, the blacks all in one section, the whites in another. We blend together more than in other parts of the country.

“It just seem like they have more problem with the blacks than we do.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s a bright fall day in Courthouse Square, and I’m looking for a place to sit down. Farmers from around Newnan, Georgia, have set up tables – displaying tomatoes and beans, pickles and jellies – and I find an empty spot next to a man on a bench.

Juggling my camera and notebook I sit, and the man and I greet one another. I ask him if he’s from around here.

“I was born in Newnan – this is my hometown,” he says, and he tells me his name is L.C. I ask if he lives nearby and he names an area that I don’t recognize. I ask him to repeat the name and, still unclear, I ask him how it is spelled. He pauses. “I ain’t been to school,” he says; “I went through the seventh grade, that’s all. I learned more stuff out of school. I was raised up on a farm.”

We talk some more, and I explain my work – photographing people, and writing about them – and then I ask if I may photograph him. “You want to take my picture?” L.C. says, then chuckles, demurs. He’s got work to do, he says. He’s not dressed right. He needs a haircut. In fact, he’s been waiting for a chair to open up at the barbershop, and is just about to go over and check. I ask if I can go with him, and he says okay.

Even though almost everyone in the square is white, inside the barbershop – just a block away – everyone is black. The barber chairs are full, so L.C. decides to wait outside, and I ask if I can wait with him. While we stand we continue to talk, and L.C. fills in a sketch of his young life.

“We were raised the hardest way,” he says, “picking cotton, pulling corn, raising sorghum cane.” He says his mother left him when he was a baby, and he was raised by an aunt and uncle, amid his cousins – fourteen kids total. As he talks I notice that L.C. doesn’t look me in the eye. When I say something he’d like me to repeat, he says, “Ma’am?,” even though he is older than I.

I ask where the family lived, and L.C. tells me they traveled from farm to farm. “I done stayed in a heap of farmers’ houses,” he says. “We didn’t have no house – that’s the way we went. Sometimes we’d wake up in a barn. We done stayed that away until we found another place to stay, you know. Back in them days, folks looked out for you if you had a bunch of children.”

“Other black folks, you mean?” I ask. “No, the whi – black folks didn’t have nothing!” says L.C. “They’d be trying to find something themselves.

“They come from slavery time,” he continues, and chuckles again. “My folks come from slavery,” he says. “Everybody you see around here: if they’re living in some broken-down house and can’t hardly make it, I guarantee their people come from slavery.” My head starts to swim, and I think of the slaves who were sold in Courthouse Square, just steps from where L.C. and I first met.

L.C. continues and describes the jobs he’s worked in his lifetime – putting cotton into the hopper at a textile mill, inspecting the lumber at a flooring factory, laying sewer pipe in the road – and I think: Here he is. Here is the man. Here are the hands, the shoulders, the arms, the legs upon which all of this was built.

Now that the barber is finally free, L.C. enters the shop, and I follow him. The television is on, and there are pictures of Barack Obama affixed to the walls. I wait in a back corner while the barber clips L.C.’s hair, trims his beard, and powders his neck. When the barber’s done, L.C. pays him, and I follow L.C. back out into the street. “I thank the Lord for the hair cut,” he says.

I think L.C. is surprised that I’ve stuck around this long, and he finally agrees to let me photograph him. But he says he wants to change his clothes first, and we decide that I’ll get in my car and follow him home. He tells me he lives with his sister, and as I follow him out of town, down a long country road, I try to imagine what the house will be like – wondering if it’ll be a “broken-down house," like the ones he mentioned. But we turn into what looks like a new subdivision, carved out of farmland: tidy houses along streets with names like Corn Row Court and Corn Crib Drive.

We pull up in front of a gray duplex with an old red truck parked outside. Inside, the house is cozy, with the dining-room table covered by a lace cloth. L.C. introduces me to his niece, who tells him that she’s left a plate of breakfast for him in the microwave. He asks me to wait while he goes to change, and while he does I look around. There on a wall, crowned with a garland of ivy, is a framed photograph of an elderly couple: a man in overalls, a heavy-set woman whose face reflects the girl I’ve just met. The frame is bordered by the letters F-A-M-I-L-Y. There they are, I think. There are the people who moved from farm to farm, with fourteen children to feed and clothe. There are the people who raised him.

After a few minutes L.C. comes out, wearing a neat black T-shirt and matching cap, and a black-leather vest trimmed in fringe. He says the vest was part of a bundle of second-hand clothes given to him by a woman for whom he does odd jobs. “I think this might be a lady’s vest,” he says. “But I like it.”

“You look real nice, Uncle L.C.,” says his niece.

The three of us go outside as the sun is starting to set. We make photographs by L.C.’s red truck, and then he asks to have some made by an old Mercury that he loves. While we work, L.C. looks straight into the camera – and finally I can really see him. My heart is getting pulled and I want to stay all evening, but I finish up and thank him and his niece. I tell L.C. that I will bring him a print, and as I drive away I can see them in the rear-view mirror, sitting on their front steps. I cross over Corn Row Court and Corn Crib Drive, and head back toward town.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On my first trip to Newnan, Georgia, I started to panic a little. I know how to talk to, and represent, those whose views I share. But the South is new territory for me, and I began to worry about understanding the people there, and representing them fairly. I wrote to a friend for help.

My friend is a Buddhist teacher. I wrote: I am in Georgia now, sussing out this project. You've reminded me that my work is to meet people, get to know them, stay open, and do my photography and writing to represent them as best I can. This is easy when I'm with someone with whom I'm "sympathetic": a new immigrant, etc.

What if I'm with someone who is patently racist, or represents a view I strongly disagree with? (A view of racism or slavery, for example.) How do I let those people speak through me, or how do I represent them in a way that doesn't compromise my own views?

She replied: I think it's always good to practice deep listening in order to understand. Ask good questions to try to get to understand the conditioning that led them to develop views different from yours. No need to have an opinion, and sometimes if we ask good questions the other person winds up understanding themselves better in the process.

Months later, on my second trip to Newnan, I walk into Trump headquarters in on Election Day. It is a small room in the back of an antiques store in the center of town. Red curtains cover the windows and “Trump” signs are stacked on the floor. The first person I meet is a blond woman wearing a red Mickey Mouse T-shirt. I introduce myself and tell her about my project. She says she’s the owner of the shop, and when I ask if I may make her portrait, she agrees.

Her name is Kelli, and she takes me into the shop, whose specialty is “vintage” toys from the 1980s – Star Wars figurines, Strawberry Shortcake dolls, Dukes of Hazzard lunchboxes. She introduces me to her husband, who once ran for Congress, as a Republican, and who set up this Trump headquarters. “You’re from Rhode Island?” he asks. “You must be a liberal.” “I am,” I say. “It’s true. But I’m trying my best to be a good listener.” They seem to like that, and I make some photographs of Kelli near the office’s red curtains. Then we sit down to talk.

I learn that Kelli was raised a Democrat, in Michigan, and that she voted for Obama “the first time.” I learn that she is a mother, a writer, and a professional poker player. I learn that she has a sister – “a Bernie supporter” – who is married to a man from Jamaica, and who has two children, whom Kelli adores. Kelli is the chair of the local organization of court-appointed advocates for children, and she considered voting for Hillary Clinton. She thinks Trump is “ignorant . . . I don’t like him as a person at all.” And about the “pussy” tape she says, “I know – I hate him for that.”

But she and her husband have struggled more each year to cover their bills, and she sees people in the community whose finances have grown more and more dire; she recently had a customer try to hock his grandfather’s sword from the Civil War. “I think we need a businessman in there,” she says of the presidency. When she learned that in 1975 Clinton had defended a man accused of having raped a 12-year-old girl, her distrust of the Democratic candidate became unbearable. “I weighed my decision very heavily,” she says. She voted for Trump.

Since the election, the media have spent much time trying to understand, and “humanize,” the people who have put Donald Trump in power. Writers of all persuasions have pleaded for empathy for Trump voters, while others are morally repulsed by this request. Back in May, The New York Times published a piece called “This Is Trump Country.” It seemed an important attempt to portray these folks in nuanced terms, to try to understand them, and I posted the story on Facebook. The rumblings from my fellow liberal friends began. Don’t ask me to understand them, or have empathy for them, said my friends. Trump voters are all racist, misogynist xenophobes.

I return to the store to speak with Kelli over the next few days. As I listen to her, I don’t agree with her conclusions: that Donald Trump will solve her economic problems, that he isn’t provoking the violence being committed in his name. But I do keep trying to listen to her. I struggle with my role: Is it, instead of listening, to try to persuade her of my views?

The day after the election, my husband rode the train to Boston behind a woman who was talking on her cell phone, explaining to someone why she’d voted for Trump. He heard her describe her soaring health-care costs, her belief in limited government, and her distrust of the Clintons. As I had done, regarding the Times story on Trump supporters, he wrote about this experience on Facebook – acknowledging his shock and disgust with Trump, but saying of this Trump supporter, “She was not crazy, or a redneck, or even remotely stupid, and she never raised her voice. She was being forced to defend her vote as though it had been an overt act of racism, or misogyny, or betrayal . . . My worry is that we are confusing the president-elect with his supporters, without ever really thinking about what motivated many of them to vote for him.”

The firestorm from our friends surprised us both. My husband was lectured on the horrors of Trump, as if he didn’t know them. He was pelted with cries of their pain, as if he were not in deep pain himself. At a gathering the next evening, one old friend – a journalist – eviscerated him for having chosen one anecdote that obscured all others. “Now I know how it feels to be screamed at by the left,” my husband told me.

I know that there is not much I can write about Kelli that could convince some that her vote was not a “hate crime,” as many consider the supporting of Trump. I understand why they feel that way. And I agree with everyone on the planet who is horrified by what a Trump administration might do, who is terrified of the vitriol he has stirred and the violence attached to his support that is being committed against the most vulnerable among us. And I truly do not understand how someone like Kelli – engaged, thoughtful, compassionate – does not see what I see.

But I know in my bones that she did not vote for Trump out of any subconscious racist or xenophobic urges. I know she’s not suffering from Stockholm syndrome, as one friend posited, about all women who voted against Clinton – that they’ve been so brainwashed by their abusers (men) that they’ve identified with them.

At the end of our last conversation, Kelli says, kindly, “Well, I’m sorry that you’re so sad about how everything played out.” She says she will read more about the attacks that I’ve told her are escalating – the hijabs being pulled off women’s heads, the swastikas that are appearing. I say I'll read up on the case of the accused rapist whom Clinton defended, about which I’ve never heard.

We could loathe and dismiss people like Kelli for having put Donald Trump in office, but I don’t understand how that moves us forward. I do know this: I liked Kelli. And I enjoyed spending time with her more than I’ve enjoyed being yelled at on Facebook by people with whom I agree.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I noticed Carmen this morning at a Veterans Day ceremony, when I heard a lady exclaim “Welcome back!” The exclaiming lady was white, wearing a pink hat, and when I turned toward her she was hugging Carmen. Bedazzled by Carmen, I introduced myself. She told me she was there to support her uncle, who had been to Iraq with the Army. She works in a beauty shop, and she has lived in Newnan all her life.

I have been in Newnan, Georgia, for exactly one week, invited here to continue my SeenUnseen work. The group that extended the invitation said that they “live in their own little bubbles, and don’t know each other;” they think my work might bridge those gaps.

There are people on both sides of many aisles who have contacted me since I arrived, expressing their investment in what I do here. There are people of color who want me to unveil the legacies of slavery, of segregation, of racist policies. There are white people who are afraid I’m “going to make them all look racist.” It is complicated, and it is really hard.

When I asked Carmen if I could photograph her, she readily agreed. She sat down at the base of a war memorial statue, “because we’re supporting the troops,” she said. It is a statue of two men in uniforms, and a boy scout holding a flag. Though they are fashioned from bronze, they have Caucasian features. I think about the ironies of those white men enshrined behind Carmen, and wonder whether they have really fought for her. I see the hand of the white man over her head and I think This is ironic. This is symbolic. People will see this in the photo, and they will question it.

I knew I’d be in Newnan on Election Day, instead of in my tiny blue state. I have made a good friend here named Cynthia, who is black. We were supposed to have breakfast the morning after the election, but I called her to cancel. I couldn’t stop crying, couldn’t get out of my pajamas. She came to the house where I’m staying anyway, banged on the door, and brought in food. She said “This is just another crash course in the South. We have been through worse, and I’m not gonna cry about this. You have got to pick yourself up, get focused, and get to work.”

Standing with Carmen at the Veterans Day ceremony, I ask her about the election. She says “We only have one President, and that’s the man up above. God is watching over him, as well as he’s watching over us.” I ask her about the prejudice, the hate crimes that are already happening; I ask her if she has felt racism here in Newnan. She says “No.”

I wonder if she feels she can be honest with me. I also wonder if it’s patronizing for my white Northern self not to believe her, or to assume that she’s missing something. I remember something else Cynthia has said to me: “I notice that you see Newnan through a very Northern lens, without seeing some of the nuances about race that are here. We do have our out-and-out racists, and then we have people who are struggling unconsciously with their own biases that were taught to them, and that our culture teaches them, that are not necessarily equitable. But it’s not as conscious as you think it is.”

I ask Carmen “If I were not a white lady, would you be able to tell me about racism here, and your experiences?” She puts her arm around me, and I suddenly feel like I’m about to cry. She says “No. I love my sisters and brothers the same. Don’t think like that. I don’t believe in that. We are different colors, but we are all the same blood.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

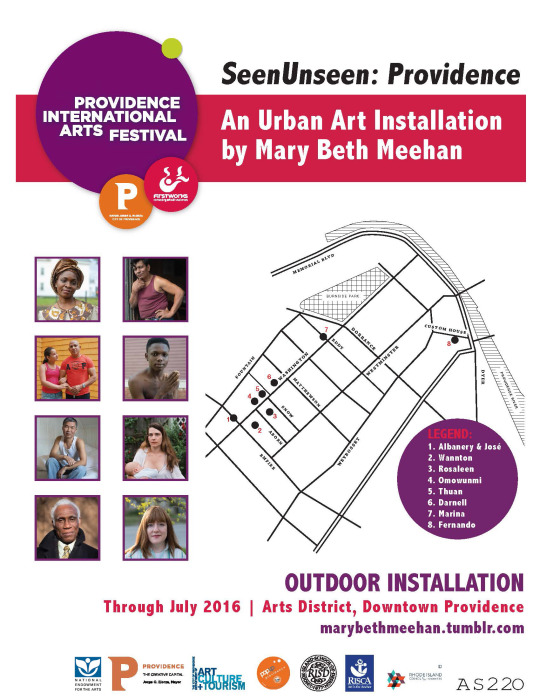

SEEN/UNSEEN Installation

With support from the National Endowment for the Arts, and in conjunction with the Providence International Arts Festival, eight portraits from Seen/Unseen have been installed as large-scale banners on buildings in downtown Providence.

Beginning with a talk at the RISD Museum, the work has launched a series of city-wide conversations about identity, community, inclusion, and visibility.

They will be on view through July of 2016. Please find map and stories below; visit artsnowri.com for more.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Marina was one of eight people who agreed to having her photograph reproduced on a large-scale banner, amid the public bustle of downtown Providence. As an Orthodox Jewish woman who practices according to the laws of modesty, this was a big decision for her.

She writes about it on her blog, Women and Jewish Tradition, and has shared her thoughts with me.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

I’m sitting in my car in Washington Park, in front of a big white house with red trim, and I can’t believe what I see: Annye is walking onto the porch and down the steps, decked out in a sun-yellow suit and plum-colored hat. After weeks of introductions and phone calls and being cajoled, she has finally submitted to my making her portrait. I’m excited but also a little worried that I won’t do her justice.

She was first introduced to me as Sister Annye, at the Bethel A.M.E. (African Methodist Episcopal) Church, on Rochambeau Avenue, just down the street from my house. I’d lived there for twelve years, often passing the tiny brick structure with its glossy red door, but had never entered. So one winter morning I decided to go there and introduce myself to the pastor. I told him I was making portraits of Providence people and that I was interested in his congregation. He invited me to a service, and told me that I had to meet Annye.

When Annye and I were introduced she was polite, but when she heard about my wanting to make photographs she said, “No, no, no!" She didn’t want to be singled out, didn’t want any “glory”; but she did give me her phone number, saying that I could call her. Nighttime was best, she said. During the day she was “always running,” doing errands for the elderly, visiting the sick. But at night she stayed home reading – the Bible and African-American history. Sometimes, she said, she’d get so engrossed in her reading that the sun would come up before she turned out her light.

Many weeks and many conversations followed. I learned that in 1959 Annye had come to Providence from Montgomery, Alabama. She’d answered an advertisement in the newspaper, placed by an East Side widower who was looking for a live-in caretaker for his three children. She met other domestic workers in Rhode Island, many of them also Southern black women – some of whom had college degrees but found that they could make more money here, taking care of white people’s children, than they could in their professions in the South.

I learned that Annye had had eight children, that all had been well educated – “Thanks be to God” – and that one had even had an audience with the pope. But there were many questions Annye refused to answer. She wouldn’t tell me her age, and was stony silent when I asked about the father of her children. “No, no, no,” she said. “That’s a sore subject.” But she finally agreed to a photograph.

So on this spring evening she gets into my car and I suggest that we go to Roger Williams Park. She agrees, saying she remembers many evenings there, with her children in pajamas, enjoying a dinner under the trees, on a broad blanket spread with chicken, potato salad, chocolate cake, and punch.

We get out in front of a beautiful old tree – “This tree is older than the both of us” – and as I work Annye is patient with me in ways I’m grateful for.

When we are finished and back in the car, she hands me something that she says she’s written and would like me to quote. Here’s an excerpt:

Annye R. P.

Community Missionary

Is a fanatic when it comes to Serving God, about Obtaining a Religious Education, Scholastic Education, Black History Education . . . . Service to your Fellow Man, Especially the Elderly, and Teaching and Training our young people to Utilize their God-Given Gifts and Talents.

Not to Expect Anything In Return but God’s Grace, Mercy, and Blessings.

When it’s all over remember whatever you have done for the last one you have also done it unto God.

May the Work I have done speak for me.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On the East Side, clustered around the Providence Hebrew Day School, on Elmgrove Avenue, is an enclave of Orthodox Jews. I live near there, and when I walk to the store or take my children to the playground, I often see the members of this community, the men wearing stiff black hats, the women with their hair covered and long skirts concealing their legs. When I pass them on foot, I say, “Hello,” but often they don’t meet my eye. Sometimes I put an extra effort into greeting them, to see if they’ll respond to me. Over time I began to notice something that I didn’t like: when they didn’t engage with me I would get angry. And when I saw the women, with their bodies encased in clothing and their many children trailing them, I would think how oppressed they must be. I’d get angry about that, too.

When I began making portraits of Providence people, I decided to try to include someone from this community. I contacted the Hebrew school's rabbi, and, after a series of phone calls, emails, meetings – and even a letter of reference – he asked me to write a short description of my work, which he said he would distribute within the community. Slowly, there followed a wave of openings; I, with my camera, began to be invited in.

I was invited to a morning prayer service, to a winter Purim parade, to a community-wide fundraiser. At one banquet a young woman approached me and said, “You must be the person who wants to meet us.” We chatted, and I asked if I could speak with her again, at her home. When I later got to her house, as arranged, she told me that she'd called the rabbi -- twice -- to make sure it was okay to let me in. Thinking of the women who didn’t say “Hello” to me on the playground, I asked her why she’d been so wary. She said that all four of her grandparents had been in the Holocaust, and that that colored the way one looked out on the world. This stopped me cold.

During the weeks that followed, I photographed many people in the Orthodox community, including students at the Hebrew school and an elderly rabbi who had taken in two non-Jewish homeless men, saying, "The Talmud doesn’t talk about love for fellow Jew – it talks about love for all God’s children.” But I remained most interested in the women.

For many of the women, the idea of being photographed conflicts with the law of modesty. This topic launched numerous conversations, in kitchens and on front steps, as the women explained to me that the law of modesty led to a kind of freedom: from the world of appearances, from the outside culture’s obsession with women’s bodies, from the gaze of men other than their husbands. Many refused to be photographed, especially if their names were to have been used and their pictures seen widely. But then I met Marina.

Marina was born in Russia and raised as a non-Orthodox Jew, but as an adult she had converted to Orthodoxy. She is now a professional in the financial sector, in Providence. She acknowledged that the law of modesty is complicated, and that in some Orthodox communities it is indeed used to subjugate women. But as someone who has chosen this spiritual path – and written two books on it – she has come to revel in the liberation that the law enables. “True beauty must stem from one’s deeds, speech, and thought, and it radiates from the inside out,” she has written. She described a culture that I know well: one that worships youth and beauty, in which adolescent girls, consumed with anxiety about their looks, often fall prey to eating disorders. Marina said that within the bounds of modesty there is room to concentrate on one’s inner virtues, to see oneself as completely human, regardless of how one’s body, social standing, or material wealth conforms to society’s standards. And she referred to the Orthodox community as a source of support, within which the outside culture’s superficial rules are irrelevant.

When I first met Marina she’d been wearing a snood, a crocheted covering of her head. When I returned to make her portrait, she was wearing a wig. It brushed her shoulders and framed her face in thick bangs. When we stepped outside to make the picture, the late-evening sunlight glinted off the auburn strands.

Back in the house, since we were just two women alone, I asked Marina if she would show me her hair. She said, “No.” She asked if I would get naked in front of a stranger, even if that stranger was another woman. I said, “Probably not.” She said that it was the same thing; my modesty was akin to hers. “It’s private,” she said.

This past weekend, a group of Orthodox women and children were at the neighborhood playground. I have a plot at the adjacent vegetable garden, and while I was working there my T-shirt and pants had gotten muddy. I spotted some of the women I recognized, and I was tempted to say “Hello” to them. But I was self-conscious about my appearance, and didn’t want to intrude. I noticed, though, that nowadays I feel differently about them.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My friend Molly is from Cambodia. She is very active within the Southeast Asian community in Rhode Island. I told her I was making portraits of Providence people, and she invited me to meet – and maybe photograph – her mother. One evening in the winter I went to see them, in the apartment house they own in Silver Lake. While I sat on the couch with a cup of tea I noticed a man walking among the rooms. He was a friend of the family who lived with them, Molly said. I found I was very drawn to this man, and I asked him if I could make his portrait.

His name is Thuan, but Molly calls him Pou, for Uncle. He speaks Khmer, and very little English, so Molly translated for us. We set up a time for me to come back to the house, and when I arrived he was waiting for me, with his hair wet and neatly combed. We made the portrait in the front room of their apartment, by a window.

When I later returned with the portrait, Thuan said he liked it. Molly said it looked as though he was between two worlds, the blank wall and straw mat reminding her of life in a refugee camp, but his tank top and jeans making him look like a cool American guy. Thuan said that the photograph was nice, but that he looked sad, even though he didn’t feel sad. When he said this, Molly made a face at me, as though she disagreed with him.

In the hour that followed, Molly told me Thuan’s story, sometimes asking him questions in Khmer, sometimes just talking while he sat quietly. The story is complicated: though he had Cambodian parents he was born in Vietnam, and in 1984, while the two countries were at war, he was mistaken for Vietnamese. He was imprisoned by Cambodian soldiers, and beaten, tortured, and forced to witness the torture of others. Molly said, “The prison in Cambodia took everything: took away his life, his soul. That’s why we love him and take care of him. Right, Pou?”

Molly said that Thuan, who is 65, now works on an assembly line in Massachusetts, putting together bottles of air-freshening spray, but that the effects of his time in prison -- backaches, migraines -- make it hard for him to hold down a job. As I listened and looked at Thuan, I grew more and more uncomfortable. I felt it would be impossible for me ever to understand these fragmented pieces of his life, and that, no matter how I presented it, it would be inadequate. Still, I said to Molly, “When you asked him if he was sad he said, ‘No,’ right?”

“Yeah, but that’s why I gave you that face,” she replied. “Because I know the truth.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Omowunmi is a soldier, a mechanic in the U.S. Army. Her specialty is “light-weight vehicles”: trucks, trailers, Humvees. She has been stationed at Fort Campbell and Fort Bragg, and was deployed twice to the war in Iraq. It was there that an accident injured her hand and ended her military career.

She told me all this inside the sweet yellow bungalow she shares with her husband, off Mount Pleasant Avenue. She’d invited me there to tell me her story. When I first arrived, we stood in the entryway talking – “Where are my manners?” she suddenly said, and took me into her living room. While we talked she served fried fish and fruit, and cold drinks.

I had first met Omowunmi at the Chapel of Peace, a small church on Potters Avenue; I’d been attracted to it by the name. Her husband, whom she had met and married in their native Nigeria, is the chapel’s pastor. She had wanted to marry a man of God, and had dreamt of him almost ten years before she met him. There were others who wanted to marry her, but she knew that he was the one.

Before coming to the United States, Omowunmi was trying to make a living in her country, selling bottled soda and bread on the roadside, when her uncle told her she’d won “the lottery.” He was in Providence, and had entered her name for a green card. She was selected.

Soon after she arrived here, almost twenty years ago, she bought a used car, for $800. It turned out to be a lemon, and cost more than that to be fixed. So that this would never happen again, she decided to learn to be a mechanic.

Omowunmi's father was a Nigerian soldier in World War II, and she adored him. He died when she was eight. From then on she’s wanted to honor him, by living a life of discipline and service – first as a soldier, now as a wife and a teacher of Sunday school, and then in whatever callings might follow.

Last year Omowunmi got her bachelor’s degree at the University of Rhode Island in health-care services, and now works at a veterans’ hospital. Her nickname is Peace. She’s thinking about changing her name permanently. It’s easier for Americans to pronounce, but, more important, she loves the word. “I love the meaning of that name.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My sons play baseball at the fields on Gano Street. I recently ran into a guy there I’d known in graduate school, whose name is Thom. I’d never associated Thom with Providence. I knew him in Missouri; he is from Virginia, but he said he’d married a woman from Rhode Island and had moved here. On this afternoon he was tending a plot at the Fox Point Community Garden, right near one of the ball fields. With him was a smiling girl in a school uniform. Her name is Elizabeth Li, and she is his daughter. Her nickname is Li Li.

On this glorious spring day, the cherry trees adjacent to the garden were in full bloom. I made some portraits of Li Li, and then we parted ways. When I had a print I went to see Thom and Li Li, in their big house off Elmgrove Avenue. Thom’s wife, a pediatrician, was out of town, so they were alone. He poured me some lemonade and puttered around the kitchen, preparing their dinner. On the cabinets all around him were magnets printed with the Chinese alphabet.

I often use my phone to record the conversations I have with people regarding the portraits I’m making, and as I later listened to my conversation with Thom I heard myself stumble: “When did you . . . ? When did . . . ? Tell me about Li Li.” Thom says he knows that as soon as people see his family – two white parents and an Asian child – they make assumptions. He says there’s a language that adoptive families learn, as in you don’t talk about the adopted child's “real” mother; you refer to her "birth" mother. And people have asked Thom if he and his wife would like “a child of their own.” “We have one” is Thom’s reply.

Thom says he knows that the complexity of a transracial adoption will be a big part of Li Li’s life, and he and his wife have focused on Li Li's learning Chinese as a bridge back to her native culture. When they first brought her here, when she was 11 months old, they hired a Chinese nanny who spoke no English. And they have since hired Chinese graduate students to tutor her. In the fall, they will travel as a family to China, visiting her orphanage and trying to meet the foster mother who cared for her.

But at this moment, it’s another gorgeous spring afternoon in Providence. We are in the family’s back yard; Thom is working the grill and Li Li is playing on her swing set. She asks me about my boys, tells me that her best friend’s name is Julia, and says that she loves to read Percy Jackson books. Her dog, which she named Ji Ji – after Jiangxi, the province where she was born – has made a mess in the grass, which she has to clean up (“It’s my responsibility”). Somewhere in the neighborhood a flute is being played. The windy notes of “America the Beautiful” are floating through the yard.

9 notes

·

View notes