Text

Last time in Letters from Watson, @paulgadzikowski provided the awesome and terrifying news that Thaddeus Sholto is meant to be modeled on Oscar Wilde. I get the strong feeling that it's not meant to be a flattering likeness.

So I was barking up the wrong tree with physiognomy. I was also envisioning something more like this villain-of-the-week from Mission: Magic! (the spiritual predecessor to The Magic School Bus).

This says more about me than about Doyle.

Last week of The Sign of the Four ("The Tragedy of Pondicherry Lodge") is filled with Exotic Adventure elements, which weirdly, for me, makes it harder to react to. In A Study in Scarlet, Doyle goes to great pains to describe the vacant house in Lambeth. This time, it's just "a huge clump of a house, square and prosaic."

The truly important thing here is that Sherlock Holmes boxes. The rabbit hole I fell down in trying to understand boxing in Victorian society is where I've been lost for so long. Boxing was simultaneously the sport of gentlemen and the lowest-class sort of pastime, plus at the time of the novel, Queensbury Rules are still new enough that the first champion under them hasn't been crowned.

Boxing is a measure of both Holmes' physical fitness and his social flexibility. He's not afraid to go fist-to-fist against a worthy opponent.

“You see, Watson, if all else fails me I have still one of the scientific professions open to me,” said Holmes, laughing. “Our friend won't keep us out in the cold now, I am sure.”

English journalist Pierce Egan coined "the sweet science of bruising" to describe prize-fighting, way back in the 1810s. Egan also published a journal called Boxiana.

Meanwhile, my cinnamon roll Dr. Watson and Miss Morstan hold hands, and I can't help imagining that it's Watson that wants support in this situation. Nonetheless, it's a relief that we're not going to play "will they or won't they?" for thousands of words. It's the 19th century: we can play "can he or can he not afford a wife?" instead.

I have no idea at all what to make of thorns, lab equipment, and the whole Pondicherry Lodge mess, so I guess I'll see what today's chapter brings.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

In both #3 and #4 of the Letters from Watson for The SIgn of the Four, Watson loses his mind and babbles when he's trying to have a conversation in the presence of Mary Morstan, and I'm here for it.

For the rest of these two letters, especially #4, I feel like I've stumbled into a story by Edgar Allen Poe or Wilkie Collins. Mr. Thaddeus Sholto feels like exactly what would happen if a colorful Wilkie Collins character -- say, the terrifyingly affable, rotund Count Fosco from The Woman in White -- stumbled into Holmes' world of deduction and logic.

Thaddeus Sholto had me digging for physiognomy texts, as that protruding lower lip feels like a detail meant to say something specific in an era that took "facial composition as a sign of character" very seriously.

The Pocket Lavatar (1817) gives us one possible interpretation:

When the lower lip projects beyond the upper, it denotes negative goodness.

Also, relevant to Sholto's watery blue eyes:

Blue eyes are frequently found in persons of phlegmatic character; they are often indications of feebleness and effeminacy.

Physiognomy and phrenology both had multiple rounds of being in fashion in the 19th century, with different gurus disagreeing on what exactly your nose or the shape of your skull meant. The whole field is, of course, wildly racist, with a garnish of ableism and a drizzle of classism. It was also a fairly familiar vocabulary to contemporary readers.

Meanwhile, I feel like every reference to Thaddeus Sholto's snobby little habits is meant to make the reader chuckle at his pretentiousness and poor taste, but I can't prove it.

Since the premise of this story seems to require acting as if plundering India for gems and wealth is okay, my hackles went up at referring to Major Sholto's long-time Indian servant as Chowdar. Turns out this was a common transliteration of a name we'd now render more like Chaudhuri.

(Major Sholto had had malaria, by the way, as evidenced from the quinine bottle present when he received his startling letter. It's likely that malaria contributed to his fragile health.)

Major Sholto's relationship with his manservant Lal Chowdar is solid enough that they hide a body together, but I have to raise an eyebrow at the major's naivete.

If my own servant could not believe my innocence, how could I hope to make it good before twelve foolish tradesmen in a jury-box?

His own servant saw how he behaved in India and probably has an accurate view of his ethics. That he'd kill out of greed happens to be wrong in this case (assuming a reliable narrator, which is a big assumption).

A face was looking in at us out of the darkness. We could see the whitening of the nose where it was pressed against the glass. It was a bearded, hairy face, with wild cruel eyes and an expression of concentrated malevolence.

My bet was "monkey," but then the Sholtos found boot prints, so either it's a monkey that wears shoes, or it's a man. Oh well.

My hackles weren't up about taking Miss Morstan's mysterious pearls from a "chaplet," but they should have been. I blush to admit that I was envisioning some sort of tiara -- but I googled before making a fool of myself and discovered that a chaplet is prayer beads. It's like a rosary, but not all chaplets are rosaries, and not all rosaries are chaplets. Is this an Anglican chaplet made from stolen gems, or were Sholto, Morstan, and their friends straight-up stealing prayer beads of another culture?

Honestly, I'm up for the Sholtos being actively cursed, but since Holmes is a rationalist, I'm also up for the more plausible outcome of their actions having brought mundane vengeance down upon their heads.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

In both #3 and #4 of the Letters from Watson for The SIgn of the Four, Watson loses his mind and babbles when he's trying to have a conversation in the presence of Mary Morstan, and I'm here for it.

For the rest of these two letters, especially #4, I feel like I've stumbled into a story by Edgar Allen Poe or Wilkie Collins. Mr. Thaddeus Sholto feels like exactly what would happen if a colorful Wilkie Collins character -- say, the terrifyingly affable, rotund Count Fosco from The Woman in White -- stumbled into Holmes' world of deduction and logic.

Thaddeus Sholto had me digging for physiognomy texts, as that protruding lower lip feels like a detail meant to say something specific in an era that took "facial composition as a sign of character" very seriously.

The Pocket Lavatar (1817) gives us one possible interpretation:

When the lower lip projects beyond the upper, it denotes negative goodness.

Also, relevant to Sholto's watery blue eyes:

Blue eyes are frequently found in persons of phlegmatic character; they are often indications of feebleness and effeminacy.

Physiognomy and phrenology both had multiple rounds of being in fashion in the 19th century, with different gurus disagreeing on what exactly your nose or the shape of your skull meant. The whole field is, of course, wildly racist, with a garnish of ableism and a drizzle of classism. It was also a fairly familiar vocabulary to contemporary readers.

Meanwhile, I feel like every reference to Thaddeus Sholto's snobby little habits is meant to make the reader chuckle at his pretentiousness and poor taste, but I can't prove it.

Since the premise of this story seems to require acting as if plundering India for gems and wealth is okay, my hackles went up at referring to Major Sholto's long-time Indian servant as Chowdar. Turns out this was a common transliteration of a name we'd now render more like Chaudhuri.

(Major Sholto had had malaria, by the way, as evidenced from the quinine bottle present when he received his startling letter. It's likely that malaria contributed to his fragile health.)

Major Sholto's relationship with his manservant Lal Chowdar is solid enough that they hide a body together, but I have to raise an eyebrow at the major's naivete.

If my own servant could not believe my innocence, how could I hope to make it good before twelve foolish tradesmen in a jury-box?

His own servant saw how he behaved in India and probably has an accurate view of his ethics. That he'd kill out of greed happens to be wrong in this case (assuming a reliable narrator, which is a big assumption).

A face was looking in at us out of the darkness. We could see the whitening of the nose where it was pressed against the glass. It was a bearded, hairy face, with wild cruel eyes and an expression of concentrated malevolence.

My bet was "monkey," but then the Sholtos found boot prints, so either it's a monkey that wears shoes, or it's a man. Oh well.

My hackles weren't up about taking Miss Morstan's mysterious pearls from a "chaplet," but they should have been. I blush to admit that I was envisioning some sort of tiara -- but I googled before making a fool of myself and discovered that a chaplet is prayer beads. It's like a rosary, but not all chaplets are rosaries, and not all rosaries are chaplets. Is this an Anglican chaplet made from stolen gems, or were Sholto, Morstan, and their friends straight-up stealing prayer beads of another culture?

Honestly, I'm up for the Sholtos being actively cursed, but since Holmes is a rationalist, I'm also up for the more plausible outcome of their actions having brought mundane vengeance down upon their heads.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

In both #3 and #4 of the Letters from Watson for The SIgn of the Four, Watson loses his mind and babbles when he's trying to have a conversation in the presence of Mary Morstan, and I'm here for it.

For the rest of these two letters, especially #4, I feel like I've stumbled into a story by Edgar Allen Poe or Wilkie Collins. Mr. Thaddeus Sholto feels like exactly what would happen if a colorful Wilkie Collins character -- say, the terrifyingly affable, rotund Count Fosco from The Woman in White -- stumbled into Holmes' world of deduction and logic.

Thaddeus Sholto had me digging for physiognomy texts, as that protruding lower lip feels like a detail meant to say something specific in an era that took "facial composition as a sign of character" very seriously.

The Pocket Lavatar (1817) gives us one possible interpretation:

When the lower lip projects beyond the upper, it denotes negative goodness.

Also, relevant to Sholto's watery blue eyes:

Blue eyes are frequently found in persons of phlegmatic character; they are often indications of feebleness and effeminacy.

Physiognomy and phrenology both had multiple rounds of being in fashion in the 19th century, with different gurus disagreeing on what exactly your nose or the shape of your skull meant. The whole field is, of course, wildly racist, with a garnish of ableism and a drizzle of classism. It was also a fairly familiar vocabulary to contemporary readers.

Meanwhile, I feel like every reference to Thaddeus Sholto's snobby little habits is meant to make the reader chuckle at his pretentiousness and poor taste, but I can't prove it.

Since the premise of this story seems to require acting as if plundering India for gems and wealth is okay, my hackles went up at referring to Major Sholto's long-time Indian servant as Chowdar. Turns out this was a common transliteration of a name we'd now render more like Chaudhuri.

(Major Sholto had had malaria, by the way, as evidenced from the quinine bottle present when he received his startling letter. It's likely that malaria contributed to his fragile health.)

Major Sholto's relationship with his manservant Lal Chowdar is solid enough that they hide a body together, but I have to raise an eyebrow at the major's naivete.

If my own servant could not believe my innocence, how could I hope to make it good before twelve foolish tradesmen in a jury-box?

His own servant saw how he behaved in India and probably has an accurate view of his ethics. That he'd kill out of greed happens to be wrong in this case (assuming a reliable narrator, which is a big assumption).

A face was looking in at us out of the darkness. We could see the whitening of the nose where it was pressed against the glass. It was a bearded, hairy face, with wild cruel eyes and an expression of concentrated malevolence.

My bet was "monkey," but then the Sholtos found boot prints, so either it's a monkey that wears shoes, or it's a man. Oh well.

My hackles weren't up about taking Miss Morstan's mysterious pearls from a "chaplet," but they should have been. I blush to admit that I was envisioning some sort of tiara -- but I googled before making a fool of myself and discovered that a chaplet is prayer beads. It's like a rosary, but not all chaplets are rosaries, and not all rosaries are chaplets. Is this an Anglican chaplet made from stolen gems, or were Sholto, Morstan, and their friends straight-up stealing prayer beads of another culture?

Honestly, I'm up for the Sholtos being actively cursed, but since Holmes is a rationalist, I'm also up for the more plausible outcome of their actions having brought mundane vengeance down upon their heads.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sign of the Four: The Statement of the Case

CW for the end of this as it includes discussions of child murder and detailed discussions of capital punishment.

Turbans have never been particularly common in the United Kingdom; these days, they are most likely to be worn by West African women or those who are undergoing chemotherapy.

It was the norm for a married woman to be referred to as "Mrs. [husband's name]", especially on something like a dinner invite. Historically, in the English common law system the United States also uses, a woman's legal identity was subsumed by her husband on marriage, in something called coverture. In some cases, a woman who ran her own business could be treated as legally single (a femme sole) and so sue someone - or be sued. This practice was gradually abolished, but did fully end until the 1970s.

@myemuisemo has excellently covered the reasons why Mary would have been sent back to the UK.

As you were looking at a rather long trip to and from India, even with the Suez Canal open by 1878, long leave like this would have been commonplace.

The Andaman Islands are an archipelago SW of what is now Myanmar and was then called Burma. The indigenous Andamanese lived pretty much an isolated experience until the late 19th century when the British showed up. The locals were pretty hostile to outsiders; shipwrecked crews were often attacked and killed in the 1830s and 1840s, the place getting a reputation for cannibalism.

The British eventually managed to conquer the place and combine its administration with the Nicobar Islands. Most of the native population would be wiped out via outside disease and loss of territory; they now number around 500 people. The Indian government, who took over the area on independence and now run it as the Andaman district (the Nicobar islands are adminstratively separate), now legally protect the remaining tribespeople, restricting or banning access to much of the area.

Of particular note are the Sentinelese of North Sentinel Island, who have made abundantly clear that they do not want outside contact. This is probably due to the British in the late 1800s, who kidnapped some of them and took them to Port Blair. The adults died of disease and the children were returned with gifts... possibly of the deadly sort. Various attempts by the Indian government (who legally claimed the island in 1970 via dropping a marker off) and anthropologists to contact them have generally not gone well, with the islanders' response frequently being of the arrow-firing variety. Eventually, via this and NGO pressure, most people got the hint and the Indian government outright banned visits to the island.

In 2004, after the Asian tsunami, the Indian Coast Guard sent over a helicopter to check the inhabitants were OK. They made clear they were via - guess what - firing arrows at the helicopter.

In 2006, an Indian crab harvesting boat drifted onto the island; both of the crew were killed and buried.

In 2018, an American evangelical missionary called John Allen Chau illegally went to the island, aiming to convert the locals to Christianity. He ended up as a Darwin Award winner and the Indians gave up attempts to recover his body.

The first British penal colony in the area was established in 1789 by the Bengalese but shut down in 1796 due to a high rate of disease and death. The second was set up in 1857 and remained in operation until 1947.

People poisoning children for the insurance money was a sadly rather common occurrence in the Victorian era to the point that people cracked jokes about it if a child was enrolled in a burial society i.e. where people paid in money to cover funeral expenses and to pay out on someone's death.

The most infamous of these was Mary Ann Cotton from Durham, who is believed to have murdered 21 people, including three of her four husbands and 11 of her 13 children so she could get the payouts. She was arrested in July 1872 and charged with the murder of her stepson, Charles Edward Cotton, who had been exhumed after his attending doctor kept bodily samples and found traces of arsenic. After a delay for her to give birth to her final child in prison and a row in London over the choice the Attorney General (legally responsible for the prosecution of poisoning cases) had made for the prosecuting counsel, she was convicted in March 1973 of the murder and sentenced to death, the jury coming back after just 90 minutes. The standard Victorian practice was for any further legal action to be dropped after a capital conviction, as hanging would come pretty quickly.

Cotton was hanged at Durham County Goal that same month. Instead of her neck being broken, she slowly strangled to death as the rope had been made too short, possibly deliberately.

Then again, the hangman was William Calcraft, who had started off flogging juvenille offenders at Newgate Prison. Calcraft hanged an estimated 450 people over a 45-year career and developed quite a reputation for incompetence or sadism (historians debate this) due to his use of short drops. On several occasions, he would have to go down into the pit and pull on the condemned person's legs to speed up their death. In a triple hanging in 1867 of three Fenian who had murdered a police officer, one died instantly but the other two didn't. Calcraft went down and finished one of them off to the horror of officiating priest Father Gadd, who refused to let him do the same to the third and held the man's hand for 45 minutes until it was over. There was also his very public 1856 botch that led to the pinioning of the condemned's legs to become standard practice.

Calcraft also engaged in the then-common and legal practice of selling off the rope and the condemned person's clothing to make extra money. The latter would got straight to Madame Tussaud's for the latest addition to the Chamber of Horrors. Eventually, he would be pensioned off in 1874 aged 73 after increasingly negative press comment.

The Martyrdom of Man was a secular "universal" history of the Western World, published in 1872.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is so much characterization tucked into "The Statement of the Case" in the 2nd of Letters from Watson about The Sign of the Four. To marshal my thoughts at all, let's go by character, starting with my cinnamon roll Dr. Watson, then turning to Holmes and to Mary Morstan.

Watson

Watson's close observation of Miss Morstan demonstrates that he's capable of making deductions from observation. He deduces from the simplicity of her attire that she has limited means, and he has a good deal to say about how the character promised by her features and manner.

In an experience of women which extends over many nations and three separate continents, I have never looked upon a face which gave a clearer promise of a refined and sensitive nature.

This is a tiny bit amusing because all of Miss Morstan's actions suggest she has the orderly soul of someone who would have been an accountant in an era more supportive of women's careers. This woman keeps receipts. She may be nervous about bringing her concerns to the Great Detective, but she's not the slightest bit delicate.

Watson seems a bit pricked in the ego by Holmes' extensive knowledge of cigar ash, as he's touting his experience with women. That would be a monograph, indeed, something sold discreetly, in a corner of the bookshop behind a curtain. I'm going to guess that the third continent, after Europe and Asia, is Africa, both because the British did a good deal of colonial meddling there and because it makes Holmes suggestion of The Martyrdom of Man so much more apposite.

Holmes

The Martyrdom of Man turns out to be a progressive best seller about world history. Author Winwood Reade's perspective is to show the importance of Africa in the development of the world. This is entirely at odds with Victorian self-confidence about the white European and American missions of colonialism. Holmes is implying, deliberately or not, that Watson knows less about at least two continents than he thinks he does.

Reade's prose feels comparatively modern -- it has the sprightly feel of early 20th century writing rather than the long, turgid sentences of the 19th century. I've been distracted by reading bits of it, as while it's not how an historian would handle its topics today, it's an interesting read.

A side note on Winwood Reade is that he was open about being an atheist, so his book is also at odds with the popular idea of Divine Providence smiling about the endeavors of the British Empire. Contemporary audiences would surely have drawn some conclusions about Holmes' religious and political leanings.

The book recommendation is preceded by Holmes establishing that he's not a sentimentalist:

He smiled gently. “It is of the first importance,” he said, “not to allow your judgment to be biased by personal qualities. A client is to me a mere unit,—a factor in a problem. The emotional qualities are antagonistic to clear reasoning. I assure you that the most winning woman I ever knew was hanged for poisoning three little children for their insurance-money, and the most repellant man of my acquaintance is a philanthropist who has spent nearly a quarter of a million upon the London poor.”

My first reaction was "welp, he really is ace, isn't he?" On reflection, I think that reaction is both right and wrong. On the side of "right," there is no way that Holmes, as written, is a neurotypical allosexual heterosexual. Asexuality is not the only possible category for him, but it's a solid contender.

On the side of "wrong," what he's arguing for from "I assure you" on is simply not to judge a book by its cover. We're used to that as a moral. We're also accustomed to believing that "body language" and such can give clues to the person within. Heck, Holmes was just on about handwriting analysis. So there's a messy little tension here between two views that were common then as now: "outer aspects reveal the person's true nature" and "don't judge a book by its cover."

Mary Morstan

I like Mary Morstan a good deal, not least because she keeps receipts.

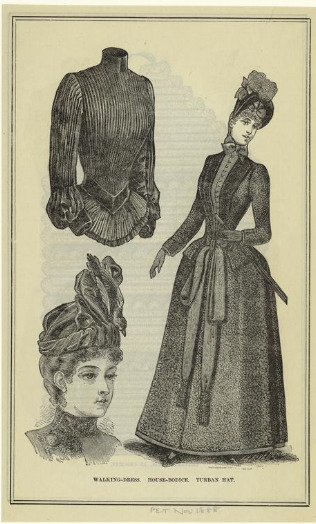

This image from the New York Public Library gives a sense of Mary's plain beige walking suit, though the feathers are far too big.

My first reaction to Mary Morstan's backstory was to check the publication date of Frances Hodgson Burnett's A Little Princess, because how many little girls were being left in boarding schools by their UK Army officer fathers who were serving in India?

Quite a few, it seems. It was standard practice to send children back to the UK to boarding school "for their health." That last euphemism raised my "what in the racist colonial claptrap" hackles, but there was a legit health concern -- malaria. Malaria is potentially deadly for anyone and worse for children, since a child who survived might have ruined health and intellectual development for life. It was not until 1897 that surgeon Ronald Ross established that malaria was transmitted by mosquitos. Miss Morstan was a child in India in the 1860s; she really would have been sent away for her own safety.

Meanwhile, although A Little Princess was published in 1905, it was expanded from a short story published in 1887. a few years before The Sign of the Four was written. That doesn't mean there's a connection: stories about a common situation and the fears arising from it are going to have similarities.

Miss Morstan's lack of English relatives did have me wondering if her mother was Indian, especially as her complexion lacks "beauty" (isn't translucently pale). Since she's blonde and light-eyed, presumably we're to assume that both parents were English or Scottish. (The genetics of eye color inheritance weren't established at all until 1907, but people obviously had folk beliefs about how much children looked like their parents, and in what ways, before that. Using today's knowledge, it seems possible that her mother had one English parent and one Indian parent, but who knows?).

At twenty-seven, she is "on the shelf" -- past the ordinary age of courtship and marriage. Her job as either a companion or a governess implies she brings no financial assets to a marriage beyond those mysterious pearls. Watson's musings that twenty-seven is "a sweet age" establishes both that he's head-over-heels for Miss Morstan and that he's enough a man of the world to prefer a woman "a little sobered by experience" to a blushing debutante.

So do the mysterious pearls mean we're going down a path superficially similar to Wilkie Collins' The Moonstone (1868), where a heroine inherits a mysterious gem from a British Army office relative? Rachel Verinder's uncle was a horrible person who came by his gem in the worst way; but Mary Morstan's father was a guard at a prison for political prisoners, which doesn't bode well for his connections. Mary has far too much good sense than to wear her pearls, though.

I do want my cinnamon roll Dr. Watson to get the girl.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

With April showers, Letters from Watson brings us the first installment of The Sign of the Four, a prospect that makes me quake. When I was a tot of eight years, reading the library's copy of The Boy's Sherlock Holmes with a creeping sense of guilt because I was not at that time (and have not been at any time before or since) a boy, I found The Sign of the Four... long. Very long. I was obviously too young for the concepts, even though I could make sense of the words. (That sums up a lot of my reading in that era.)

I'm also reeling from last week's "The Man with the Watches," an utter tragedy of "be gay, do crime."

What's striking me this time -- what with the introduction of Holmes' cocaine use and also the watch deduction that raises a wince and a shudder from anyone who remembers that BBC Sherlock happened -- is how Watson is being positioned (and I don't mean "positioned in the path of which bullet," though apparently he got hit by more than one while in India).

Cocaine

Watson is progressive! His objections to cocaine sound so mild to us in the twenty-first century, but in 1890, scientific opinion was just barely starting to turn away from seeing cocaine as a wonder drug. It was used for local anesthesia as well as for general pep. Queen Victoria drank Vin Mariani, a wine fortified with cocaine, and so did the Pope. Coca Cola contained cocaine until 1906. Sigmund Freud was a vocal proponent of cocaine for improving mood and performance, until he botched an operation in the early 1890s while high.

A couple hair-raising reads on this topic are Cocaine: The Victorian Wonder Drug and A Cure for (Anything) that Ails You: Cocaine in Victorian Medicine.

So Holmes' original audience would have seen him as an up-to-date scientist using a socially approved means of moderating his mood. His shooting up a 7% solution of cocaine is about equivalent to a 21st century person taking nutritional supplements that are meant to boost brain power.

After all the "say no to drugs" education in the American school system, that's so hard for me to get my brain around, but there we are. Holmes is doing something no more troubling than pouring a glass of whiskey and much more scientific.

Watson, therefore, can be read either as being right at the edge of shifting scientific opinion or as being a fussbudget.

Tinge it with romanticism

I'm firmly Team Watson when Holmes starts criticizing A Study in Scarlet:

He shook his head sadly. “I glanced over it,” said he. “Honestly, I cannot congratulate you upon it. Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science, and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism, which produces much the same effect as if you worked a love-story or an elopement into the fifth proposition of Euclid.”

The reader is being positioned here to view with contempt the exact features of the work that we probably enjoyed. Poor Watson!

Is it possible that some reviewers commented on the melodrama of the Lucy portions? Yes, and it'd be a valid point. Nonetheless, having experienced a good many math classes, I think the fifth proposition of Euclid might be improved by a rom--

wait.

Doyle, you magnificent bastard.

Flatland: A Romance in Many Dimensions was published in 1884. It wasn't a huge success, but it seems likely Doyle could have known it, and it did, in fact, mention a love story in a discussion of angles. Back when I read it in college (because if you "liked math," someone would inevitably give you a copy of Flatland), I missed the social satire but appreciated the geometry.

Watson is canonically an effective popular writer, and I refuse to denigrate him for that.

The Watch

First, Holmes substantially invents forensic science with his monographs on tobacco and on callouses.

Then we learn that Watson is a second son, which fits with his his training for a profession and choosing the army to help make his way.

Watson was not on great terms with his brother before his brother's death. Holmes doesn't explicitly deduce this, but it's there to be deduced. Holmes knew Watson's father was long dead, which could have come up in any number of casual ways. Holmes had no idea that Watson had a brother, so Watson:

Didn't mention the brother in any context, ever.

Didn't set up any framed daguerreotypes from his childhood nor any modern photos made with the collodion process. Having a posed family photo would have been so completely normal, as would being sent new photos by family members.

Never interrupted his routine to visit his brother while living with Holmes.

Did not attend his brother's funeral (unless it took place while Holmes was away) and did not wear a black armband for mourning in Holmes' presence. Neglecting mourning for a relative would have been a sign of serious estrangement.

Holmes is possessed of some level of tact in not expanding on this topic.

Watson is also nobody's fool: he knows there are ways to fool a mark with apparently miraculous knowledge.

The question in my mind is this: did Watson deliberately distract Holmes from asking what was the subject of the telegram?

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wait, wait, there's one last Letters from Watson for A Study in Scarlet, and it has the ANSWER to my question from the last one.

Having left the house, I proceeded to do what Gregson had neglected. I telegraphed to the head of the police at Cleveland, limiting my enquiry to the circumstances connected with the marriage of Enoch Drebber. The answer was conclusive. It told me that Drebber had already applied for the protection of the law against an old rival in love, named Jefferson Hope, and that this same Hope was at present in Europe

So Drebber not only asked for police protection, but the police were motivated to trace Hope to Europe. Drebber must surely have been very rich to get this level of service for his tax dollars.

The rest of Holmes' explanation is such an interesting reveal of how important contextual knowledge is. It's obvious enough when he's first investigating that the carriage wheel tracks mean something, but as a twenty-first century digital gal, I could never have filled in the blanks on the difference in carriage wheel gauge.

My 13 days of Duolingo Latin (it's a very short course) gave me a working knowledge of drunken parrots in the marketplace, but nothing sufficient to the final quote. (I cannot decide if I envy or sympathize with the generations of English public school boys who had to learn Latin and Greek. The skill seems handy -- and characters certainly quote at one another madly in novels -- but it's never so handy in real life that I do anything about it. Everything gets easier by the Golden Age of Mysteries, when the aphorisms are as likely to be in French.)

People hiss at me, but I applaud myself

At home, I contemplate the money in the box.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Watson has, at long last, reached the end of A Study in Scarlet. Of course, @thefisherqueen turns out to be absolutely correct that Drebber was willing to go arm-in-arm with his killer because he was falling-down drunk.

One day the professor was lecturing on poisons, and he showed his students some alkaloid, as he called it, which he had extracted from some South American arrow poison, and which was so powerful that the least grain meant instant death.

Wait! It's the mysterious untraceable South American dart poison that Agatha Christie and her generation of mystery writers will mock mercilessly! That's actually rather cool -- this isn't necessarily the trope-codifying instance of that poison, but it'd be a tale that writers of the Golden Age had in mind.

All our questions are answered except one. When Lestrade (I think) wired to Cleveland for information on Drebber, Holmes complained that he'd missed questions he should have asked. What were they? Drebber's whole sordid history would have been known to authorities -- or anyone -- in Cleveland only if he'd volunteered the information. "Oh, by the way, I belonged to a Mormon secret society, had eight wives, and abetted murdering the father of my unwilling ninth wife" is not at all the sort of revelation that gets made in polite drawing rooms. Record-keeping was so localized that Drebber could have had wives in Columbus, Akron, Toledo, and Dayton without anyone in Cleveland knowing.

Like Holmes, I'd like to meet the friend of Hope's who is so adept at playing parts and hopping out of cabs, but it is not to be.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gorgeous wilderness description opens "The Avenging Angels," part 12 of Letters from Watson. I wonder how much was inspired by Sir Richard Francis Burton's The City of Saints, recounting his travels in the west and visit to Brigham Young.

Our fleeing party is initially in the Oquirrh Mountains west of Salt Lake City.

The modern highway route skirts the Oquirrhs, in favor of a straight run across the salt flats.

If Ferrier, Lucy, and Jefferson Hope really made 30 miles in their first days, they reached the Cedar Mountains, which are less terrifyingly craggy but very much a desert. Deseret Peak is the pinnacle of this range, though any route across would look for a lower pass.

Were they to make it into what's now Nevada -- with Carson City clear the other side of the state -- there'd be a lot more of this. It's not hospitable country even today.

The big horn sheep is exotically western! And genuine! I am distracted from Jefferson Hope's wasting much of his kill by the discovery that the Sierra Nevada mountains (California - Nevada border, nowhere near our fleeing party yet, but important to me IRL) have their own genetically distinct big horn population.

Hope's slaughtered big horn is likely a Rocky Mountain big horn.

Of course, it's all a disaster. Everyone had to be doomed by the narrative in some way.

But we get an exact date: August 4, 1860.

Camp Floyd, the U.S. Army camp for the occupation of Utah following the Utah War of 1857-8, was right at the south end of the Oquirrh Mountains. Jefferson Hope had the option of hiding Ferrier and Lucy in the mountains and walking them right into the protection of the U.S. military. Maybe there were too many LDS settlers in the low spots in between (though I think Doyle didn't know or remember that the Utah War had happened).

Now comes the crucial moment that chafes me hard.

As the young fellow realized the certainty of her fate, and his own powerlessness to prevent it, he wished that he, too, was lying with the old farmer in his last silent resting-place.

Again, however, his active spirit shook off the lethargy which springs from despair. If there was nothing else left to him, he could at least devote his life to revenge.

What about rescuing Lucy after she's married? Okay, Jefferson Hope can't get back to Salt Lake City in time to prevent a forced marriage. However, we're told later that she was a marriage prize primarily for control of her father's property. Once that's in the hands of her husband, would he bother pursuing her? In this period, marriage would make it his and eliminate her rights to it. (I'm assuming nobody is disputing the legality of polygamous marriages in this universe.)

Jefferson Hope really seems to buy in that once married (against her will), Lucy is legitimately another man's property. Admittedly, it's an era when pressuring an heiress into marriage was seen as fairly acceptable, if one's table manners were good. The burden was on the young woman to be too wise and firm to give in, and yet when Lucy shows fine judgment and takes action to avoid the match, she's taken by force. The system is so completely rigged against her; no wonder she can't find any hope to live for.

The schism that sends Drebber and Stangerson on their merry way appears to be fictional, as the Reorganized LDS under Joseph Smith III in the Midwest is too early (1861) and the Godbeites in SLC is too late (1869).

By the end of Jefferson Hope's epic pursuit from Russia to France to Denmark to England. we have now accounted for Drebber's existence in Cleveland, his employment of Stangerson, the gold ring, and the note about how Jefferson Hope is in Europe.

We have not accounted for why Drebber would go arm in arm with his enemy into a vacant house.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

With the latest Letters from Watson, we are back in the story's present. There, we discover how Jefferson Hope got to drive a cab when there's no way he had The Knowledge of London's streets: he was the 1880s equivalent of the guy with no valid license who shows up as your Uber ride, despite the app showing someone else entirely.

Seriously, I've been reading "Cab Cultures in Victorian London: Horse-Drawn Cabs, Users and the City, ca 1830-1914," a Ph.D. thesis by Fu-Chia Chen in the University of York's Railway Studies program. Relevant things I've learned:

Making a living as an owner-operator was difficult (horse maintenance was expensive) and often required renting out the equipage to others, to keep the carriage in operation 24/7. (Thus Jefferson Hope's arrangement.)

Hope should have been alternating two horses with the hours he was driving, between earning actual money and tailing Drebber.

While drivers who rented their cab should have been licensed, there were numerous owner-operators who rented cabs to drivers who were unlicensed or had lost their licenses.

Hope's strategy of working only obscure hours and spending the better part of the day tailing Drebber was just as bad an idea for making money as it sounds like.

Hope's reliance on a map also probably did not go quite as swimmingly as he claims.

Meanwhile, Watson reminds us that he, too, can draw a conclusion from available evidence, when he correctly diagnoses Hope's aortic aneurysm. I was curious enough about that to wiki-walk it, and either Watson is a medical genius or Hope is about ready to pop, as that buzzing sound is supposed to only be heard in the very late stages of the ailment.

I feel like we're supposed to like Jefferson Hope as a manly forthright bold man, and at this point... I kind of don't? At the moment I like Watson most, as he's handling a wild week with aplomb and enthusiasm.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gorgeous wilderness description opens "The Avenging Angels," part 12 of Letters from Watson. I wonder how much was inspired by Sir Richard Francis Burton's The City of Saints, recounting his travels in the west and visit to Brigham Young.

Our fleeing party is initially in the Oquirrh Mountains west of Salt Lake City.

The modern highway route skirts the Oquirrhs, in favor of a straight run across the salt flats.

If Ferrier, Lucy, and Jefferson Hope really made 30 miles in their first days, they reached the Cedar Mountains, which are less terrifyingly craggy but very much a desert. Deseret Peak is the pinnacle of this range, though any route across would look for a lower pass.

Were they to make it into what's now Nevada -- with Carson City clear the other side of the state -- there'd be a lot more of this. It's not hospitable country even today.

The big horn sheep is exotically western! And genuine! I am distracted from Jefferson Hope's wasting much of his kill by the discovery that the Sierra Nevada mountains (California - Nevada border, nowhere near our fleeing party yet, but important to me IRL) have their own genetically distinct big horn population.

Hope's slaughtered big horn is likely a Rocky Mountain big horn.

Of course, it's all a disaster. Everyone had to be doomed by the narrative in some way.

But we get an exact date: August 4, 1860.

Camp Floyd, the U.S. Army camp for the occupation of Utah following the Utah War of 1857-8, was right at the south end of the Oquirrh Mountains. Jefferson Hope had the option of hiding Ferrier and Lucy in the mountains and walking them right into the protection of the U.S. military. Maybe there were too many LDS settlers in the low spots in between (though I think Doyle didn't know or remember that the Utah War had happened).

Now comes the crucial moment that chafes me hard.

As the young fellow realized the certainty of her fate, and his own powerlessness to prevent it, he wished that he, too, was lying with the old farmer in his last silent resting-place.

Again, however, his active spirit shook off the lethargy which springs from despair. If there was nothing else left to him, he could at least devote his life to revenge.

What about rescuing Lucy after she's married? Okay, Jefferson Hope can't get back to Salt Lake City in time to prevent a forced marriage. However, we're told later that she was a marriage prize primarily for control of her father's property. Once that's in the hands of her husband, would he bother pursuing her? In this period, marriage would make it his and eliminate her rights to it. (I'm assuming nobody is disputing the legality of polygamous marriages in this universe.)

Jefferson Hope really seems to buy in that once married (against her will), Lucy is legitimately another man's property. Admittedly, it's an era when pressuring an heiress into marriage was seen as fairly acceptable, if one's table manners were good. The burden was on the young woman to be too wise and firm to give in, and yet when Lucy shows fine judgment and takes action to avoid the match, she's taken by force. The system is so completely rigged against her; no wonder she can't find any hope to live for.

The schism that sends Drebber and Stangerson on their merry way appears to be fictional, as the Reorganized LDS under Joseph Smith III in the Midwest is too early (1861) and the Godbeites in SLC is too late (1869).

By the end of Jefferson Hope's epic pursuit from Russia to France to Denmark to England. we have now accounted for Drebber's existence in Cleveland, his employment of Stangerson, the gold ring, and the note about how Jefferson Hope is in Europe.

We have not accounted for why Drebber would go arm in arm with his enemy into a vacant house.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

POLYGAMY. In "A Flight for Life," this week's Letters from Watson, young Joseph Stangerson just oh-so-casually mentions that he currently has but four wives, while young Drebber (proven uncouth by having his hands in his pockets and whistling) already has seven.

Poor Lucy! Having come into the chapter with the assumption that, since other wives hadn't come up in Brigham Young's original visit, Lucy would be wife #1, this revelation seems much worse. Women are not Pokémon: no need to catch them all.

As an aside, where are Lucy's friends among the girls of Salt Lake City? Ferrier attended religious services. She must surely have socialized with other girls. Making her Not Like Other Girls seems othering toward the rest of the women: whether they were stolen from wagon trains, born to the culture and miserable, or born to the culture and relatively happy in working the system to be comfortable-ish, they were also people with thoughts and value.

Utah's Adventure Family does a photo tour of the Jacob Hamblin Home, where the parlor seems plausible to envision as Ferrier's parlor, right down to the rocking chairs -- here. Hamblin's stone house was built as part of a mission to convert the local Paiutes. Part of the reason for that U.S. Army expedition in 1857 was fear that the LDS community was turning the native peoples against Americans (which, given how badly Americans and our government treated the natives, would not be that difficult to do).

Horror! Mystery! Ninja Danists! White hero who knows the ways of the native peoples! (That's a trope.) Does Lucy know anything that's going on? Her Victorian purity seems to be winning over her Spunky Western Girl nature, even before we get her "death before dishonor" line.

So we're off to Carson City, Nevada. This means it's definitely at least 1859, since the city wasn't founded until 1858, as a deliberate effort to set up a capital for a proposed Nevada Territory that would separate Nevada's small population from the Utah Territory. The miners and opportunists in Nevada didn't like being governed by the LDS leaders in Salt Lake City. (Brigham Young was governor of the whole territory until the 1857-8 Utah War that appears not to have happened in this timeline.)

Carson City is a long walk. Google Maps is giving me 192 hours, mostly along what's now US-50, known as "the loneliest road in America." Even if we posit more activity due to miners heading west, it is still a haul across rugged mountains, and so, so much desert. (The route does legit skip the salt flats.)

If nothing goes wrong, our little party will be on the road for about a month, through hostile terrain. When they arrive in Carson City (population 714), they'll still be technically within the Utah Territory, as Nevada Territory wasn't split off until 1861. However, it'd take a determined party to come after them, and they wouldn't get a friendly welcome.

(Carson City now has a population of about 60,000, along with the state capitol, some nice late Victorian architecture, and a bunch of antique stores. It may be my favorite spot in Nevada.)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

As "John Ferrier Talks with the Prophet" in Letters from Watson, I'm sucked down the rabbit hole of Mormon Escapee Narratives.

There were several that were wildly popular in the years between the LDS settlement of Utah and the time when Doyle was writing. The one I can find an online copy of is Fanny Stenhouse's memoir, which appears to have had a couple versions under variant titles. The one I've paged through is Tell It All: The Story of a Life's Experience in Mormonism (1879, with foreword by Harriet Beecher Stowe). There's also an 1872 version titled Exposé of Polygamy in Utah: A Lady’s Life among the Mormons.

Fanny Stenhouse's existence is documented, and she went on the lecture circuit in the 1870s as an opponent to polygamy.

Her story matches Doyle's description of conspiracy theories, secret organizations, and atrocities in Salt Lake City so closely that it's likely he got his ideas from Stenhouse or similar materials. Newspaper coverage of happenings in remote Utah would, whether in London or Edinburgh, have been scanty and sensationalist -- although there is one historic event that might have excited interest, and its absence from the story muddles the timeline.

In spring 1857, President Buchanan sent the U.S. Army to the Utah Territory. The LDS residents feared renewed persecution, turned plowshares into swords, and fought a guerilla war of annoyance against the army. In September 1857, a group of Mormon militia slaughtered an entire wagon train of settlers bound for California (the Mountain Meadows Massacre). The wikipedia entry linked is worth a read, as it captures the "what really happened? who lied about what? was this an LDS policy or a group that acted recklessly on its own?" questions that swirl around efforts to make sense of the history of this era.

The "Utah War" wasn't the first incident of violence between LDS and "gentiles." Back in 1838 in Missouri, harassment and violence toward LDS settlers was met with the formation of the Danites (aha! Doyle mentions them!), a vigilante secret society that retaliated violently. The 1838 Mormon War is an appalling read on so many levels.

Whether the Danites were still operating in the 1850s in Utah is a question that historians today dispute. Their reputation in the 1830s was that they were determined to remove dissent within their own people, so the idea that forces within the LDS community would silence a man for disagreeing has some historical basis.

What's seriously missing in Doyle's account is that in 1858, Brigham Young's plan for thwarting U.S. troops was to evacuate Salt Lake City -- so thousands of LDS faithful boarded up their homes, gathered their goods, and marched off into the mountains. (There was talk of burning the city, but that apparently didn't happen.) Obviously, people came back, but that's a big thing for John Ferrier to have lived through without remarking upon. A year of widespread want from culling herds and missing portions of the planting season, combined with military occupation, seems like a big deal.

If we assume none of that had happened yet, then it's early 1857 and only 10 years since Ferrier and Lucy were rescued -- making his twelfth year of wealth in the future, the discovery of silver in Nevada also in the future, and Lucy just fifteen. The latter is still plausible for her being pressured to marry, alas. I think the timeline's just a bit muddled, though -- even with today's online resources, researching 30-year-old events in a far-away place can get messy.

Ferrier's unwelcome visitor is none other than Brigham Young, charismatic leader of the LDS community, and governor of the Utah Territory from 1850 to 1858. He was also a Freemason (remember the Masonic ring, weeks ago?).

Polygamy doesn't come up! What?!? We're in a generic sort of romance plot, where the innocent flower is to be given to a less noble and honest man than her preferred suitor. We know that the Drebber son is going to turn out to be a terrible man, but there's nothing especially indicative of it in Brigham Young's proposal. Since there's no mention of young Drebber or young Stangerson having pre-existing wives, it's likely Lucy is being offered the position of the legally married first wife.

Ferrier's plan is to flee. Since Doyle's readers are in the future, they may have a tingle of fear related to the doctrine of "blood atonement" (which was discussed in Stenhouse's book as well as in newspaper accounts) and the 1866 murder of Dr. Robinson.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm still back on "The Flower of Utah" in Letters from Watson, so let's do some early Utah houses, thanks to Wikimedia Commons.

Here's one of the two surviving cabins from the first LDS settlers, built in 1847. This one belonged to Osmyn and Mary Deuel. John Ferrier's initial cabin would have looked a lot like this.

The idea that settlers would just expand the cabin, rather than building a fresh impressive house, is very different from my experience of settlement sites in the midwestern and western states, so I think Doyle was making up what he liked the sound of.

Building something like the Clark-Taylor house (1855-ish) seems more likely.

How Ferrier worked his land so effectively with no help from wives or children is a mystery. We'd have to be eliding some form of itinerant labor from young white men or natives passing through, or else he's hiring other people's excess children -- or it's just a handwave that Ferrier is just that much hard-working and resourceful. The plot requires Ferrier to prosper so that there can be a rich inheritance for Lucy.

Ah, Lucy! She's a standard-issue Spunky Western Girl, frequently seen in literature of the 1910s-1950s. Honest-spoken, brilliant on a horse, capable as a man but imbued with maidenly modesty -- she's a type. I'm surprised to encounter her in a story written in the 1880s, but most of my exposure is from when I lived in Arizona, which only became a state in 1912. Lucy is definitely a participant in the Victorian-era belief (not universal, but having strong outbreaks from time to time) that fresh air, exercise, and frontier society were better for health than stuffy drawing rooms.

If it's been 12 years (based on Ferrier's rise to wealth), then it's 1859 and Lucy is about 17, or (in the norms of the time) right at a liminal state of being ready for a push to leave the innocence of girlhood for the responsibilities of womanhood. The push to do so doesn't, narratively, have to be a man -- it can be a hardship, a loss, or other trial. But here comes Jefferson Hope!

Hope is here to raise money for silver mining in Nevada, which started its silver rush a year earlier with discovery of the Comstock Lode. The hard-faced, dark adventurer who entertains the maiden with his stories is also a trope of the era, one that really takes off in the 20th century, where it becomes an impetus for the girl to seek out adventure, too.

Hope and Lucy are engaged, all is well -- except, of course, we know it isn't. Polygamy still hasn't come up! Where are Lucy's other suitors? Surely the Flower of Utah had some!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On the Great Alkali Plain" part 2, from Letters from Watson, arrived in my inbox this morning, bringing with it a predictable cloud of dust from approaching horses (since this isn't a George R.R. Martin novel, so we're not going to introduce characters just to kill them off immediately).

But what a caravan! When the head of it had reached the base of the mountains, the rear was not yet visible on the horizon. Right across the enormous plain stretched the straggling array, waggons and carts, men on horseback, and men on foot. Innumerable women who staggered along under burdens, and children who toddled beside the waggons or peeped out from under the white coverings.

Either we're running late on the Oregon Trail (since Doyle did not have social media to live-blog progress across the dusty waste) or the year 1847 is important, and these are Mormons.

“Shall I go forward and see, Brother Stangerson,” asked one of the band.

These have got to be Mormons.

“Nigh upon ten thousand,” said one of the young men; “we are the persecuted children of God—the chosen of the Angel Merona.”

Tell me you're a Mormon without telling me you're a Mormon.

“We are the Mormons,” answered his companions with one voice.

OMG, they're Mormons.

This makes the geographic names a little dicey -- the Mormon Trail ran through Wyoming, similar but not identical to today's I-80, so the Rio Grande River should be nowhere nearby -- but Doyle didn't have access to Google Maps, and it's not like his readers in the UK would go factcheck. Even with the Transcontinental Railroad completed back in 1869, most places in the Great American Desert were still remote in the 1880s, and California on the far end was still feeling the effects of isolation. Doyle also misspells the Angel Moroni and uses a masculine-ending name on a Sierra, so he's working from popular myth and the memory of things he's read. I wonder how many letters with corrections he received.

(At the time Doyle was writing, "Mormon" was the term used by the group themselves. Since about the 1980s, church leadership started urging the use of "Latter-Day Saints" instead. When I lived in Phoenix, that's near a big LDS population in Mesa, so I wince at using the older term. From here on out, if I'm quoting Doyle, I'll use "Mormon," but if I'm talking, I'll stick to LDS.)

The big reason the LDS wagon train is headed west is because they practiced polygamy at the time, and this was considered both illegal and immoral in larger U.S. society. (That's not a critique of polyamory today, when enthusiastic concept and clear rules are normalized.)

So far Doyle's account of the LDS party is generally positive -- they're organized, efficient, knowledgeable about their surroundings, prepared for danger, and responsible toward people needing rescue, if a bit holier-than-thou -- but I can't believe he's going to handle polygamy with anything other than distaste.

Polygamy is the thing LDS have been known for (to their chagrin after the mainstream LDS church banned it), so at the end of this section, Doyle's original audience is split into two groups:

Readers who have no real idea what a "Mormon" is and accept it as just one more crazy American thing, who now figure Lucy is rescued and wonder what goes wrong later to lead to murder; and

Readers who know about polygamy and are feeling dread for Lucy.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Suddenly, Letters from Watson dumps us in the middle of the Great American Desert (part 1 of "On the Great Alkali Plain," 2/7/24). This is not anywhere I expected to be transported from London, and the contrast makes the Mountain West feel exotic for a minute.

The Great American Desert -- stretching from about Grand Island, Nebraska to the Sierras and pretty much the entire north-south length of the U.S. -- had become a thing of legend since explorers' accounts in the 1820s. When Dad and I drove across it in 2022, we talked about how incredibly daunting it must have been for emigrants seeking their land of milk and honey on the Pacific coast.

The way we went, out I-80, Nebraska shifts from green to gray as it rises toward the Rockies. After a while, the wind picks up as you go uphill into Wyoming. There's a lot of Wyoming, and after Cheyenne and Laramie (both of which would be small towns in most states), it's very, very empty. When we finally started the descent toward Salt Lake City, and the little valleys beside the road turned green with running water, it was truly like entering paradise.

Of course, in 1847, Salt Lake City was just barely being settled, as Brigham Young led his Latter Day Saints west from Council Bluffs, and its location wasn't part of the U.S. yet.

The Mexican-American war had started the prior year, 1846, and was still going. Spring-summer of 1846 saw the Bear Flag Revolt in California, followed by the U.S. just annexing the state. Gold wouldn't be discovered at Sutter's Mill until 1849, so while emigration to California happened -- the Donner Party made their ill-fated trip in 1846-47 -- it wasn't anything like the scope of movement along the Oregon Trail.

As far as I can tell, "Sierra Blanco" is not a real place. There's a Sierra Blanca in New Mexico -- which would fit with all the specific landscape, plus White Sands National Park in New Mexico specifically has alkali flats. Last time I drove through New Mexico on I-40, in late 2018, it was delightfully desolate, so I can buy that in 1847, it seemed completely empty, with even the native peoples avoiding some stretches.

Why anyone would be crossing New Mexico is a mystery, since neither Arizona nor southern California were much settled by Americans. There was some sort of wagon route across New Mexico used by U.S. soldiers during the Mexican-American War, so if I'd expect anyone to be about, it'd be the U.S. Army.

Utah, now, is downright famous for its salt flat, but that's west of the site of Salt Lake City.

Regardless, parties screwing up their trip to the west by taking an imprudent shortcut or mistaking the route was definitely both a thing that happened and, thanks to the Donner Party, a trope. Our haggard and starving traveler sounds about right.

Then he reveals a Plucky Innocent Victorian Child.

That "pretty little girl of about five years of age" is the absolute ideal of Victorian childhood, being perfectly behaved, utterly imperturbable, determined to see the best in all things, sweet, trusting, and looking forward to being reunited with her mother in heaven.

This kind of child is why Louisa May Alcott was seen as innovative for writing Little Woman about girls who worked on their character flaws. (This is also the ideal the March girls were being aimed at. Polly in An Old-Fashioned Girl comes closer, but even Polly would have been upset about being hopelessly lost in the desert with no water.) Contrast this with the street urchins that Holmes employs in his investigation, who are good enough sorts but scrappy, resourceful, and street smart.

Ordinarily, a Victorian child who was utterly sweet and pious would be a cinnamon roll, literally too good, too pure for this world, and thus would die beautifully but tragically before long. Being lost in the desert seems ideal for this, but --

She turns to prayer, and since someone must survive in order for this scene to be relevant,

Yes, darn it, I am on the edge of my seat to know what happens. I'm also grateful that crossing the Great American Desert in 2022 was a quicker process. I've been reading Carey Williams' old-but-interesting California: The Great Exception, which has a lot to say about how 19th century isolation shaped California's economy and power structure, not always for good. But that's neither here nor there -- I don't think we're headed to California.

21 notes

·

View notes