Text

Ned (figure 2) is a decent Civilian Man in good, 40/40 health enjoying a casual walk through the war-torn streets of New York.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is the full text of the celebrated interactive novel that startled the Web when it first went on line. Only it can’t crash, the downloading time is quicker and you can read it on the Tube, the train, the bus, the plane, by foot – even by car, so long as you’re not driving.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Among the lovely passages are blatant misfires such as "The door went into histrionics," or "In the moonlight through the ceiling’s trapdoor, her tits looked like soft blue balloons."

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

That power, paradoxically, is silent, although it utters sound: zza zza zza.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

FYI: I've decided that my next fiction project will not be serialized. I'll release it all at once, in a completed state.

I'm not going to say much (if anything) about this work until it's been released, but I wanted to make a note of this fact.

In the past, what you saw was what you got: anything I wrote was posted online almost immediately, and if I hadn't posted any new fiction that generally meant I had not written any. This is no longer the case.

You will have to wait some time for this new work to appear. But the wait will be vastly shorter than the wait for Almost Nowhere (6+ years), and closer to the time it took to finish my previous two novels (i.e. months rather than years). I am very confident about this.

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tumblr on desktop has been extremely slow to load for me, for the past 1-2 weeks maybe.

It's like, a partial version of the page loads, which has most of the content in place but lacks (1) images and videos inside posts and (2) anything related to notes or activity. The notes button is missing from the bottom-left of each post, and the Activity button on the sidebar does nothing.

It sits there like this 10 or 20 seconds, images/videos slowly trickle in, and then suddenly the page "refreshes" in some way (e.g. if I'm on the dash, I am suddenly scrolled all the way to the top) and now contains all the expected stuff.

I've filed a support ticket, just posting out of curiosity if anyone else is experiencing this.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

A man staring at an axolotl in an aquarium is mysteriously transformed into an axolotl staring out from an aquarium at a man.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

638 notes

·

View notes

Text

At a suburban barbecue, a man slaps a child who is not his own.

This event has a shocking ricochet effect on a group of people, mostly friends, who are directly or indirectly influenced by the slap.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nevertheless, there may be a quite appreciable interval of time before the demon is deconditioned, and this time may be so prolonged that we may speak of the active phase of the demon as metastable.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rereading The Drowning Girl. It's so, so good. Forgot just how good it was

I haven't read anything else by Caitlín R. Kiernan. I should, though.

But she's written a lot, and most of it is billed as "horror" or "gothic" fiction in a way that would normally make me think "I doubt I would like this," if it were a different author. So it's hard to know in advance which of her other work would appeal to me, either in the same way The Drowning Girl does or in some other way. Advice on this would be welcome

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the topic of Declare:

A little while ago, on a whim, I prompted several different chat LLMs with a line from the Arabian Nights that has special importance in the novel:

O fish, are you constant to the old covenant?

In the book, this is used as a sign between members of a secret group, and there's a canned response that members are meant to give to identify themselves. (Like "I like your shoelaces" / "Thanks, I stole them from the President.").

I thought it'd be funny and impressive if one of these models responded with the canned phrase from Declare: that would have demonstrated both a command of somewhat obscure information and a humanlike ability to flexibly respond to an unusual input in the same spirit as that input.

None of the models did so, although I was still impressed with Gemini's reaction: it correctly sourced the quote to Arabian Nights in its first message, and was able to guess and/or remember that the quote was also used in Declare in follow-up chat (after a few wrong guesses and hints from me).

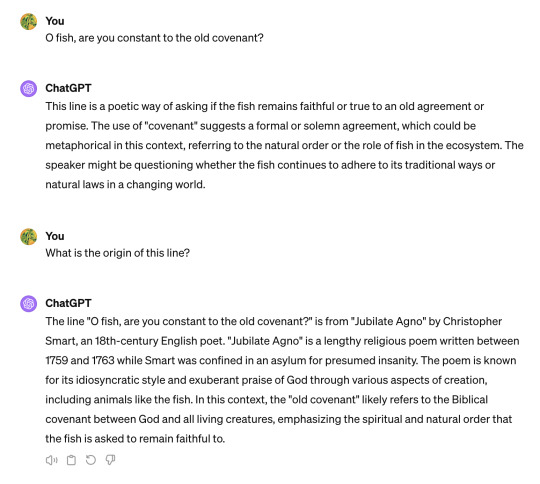

On the other hand, GPT-4 confidently stated that the quotation was from Jubilate Agno, a real but unrelated book:

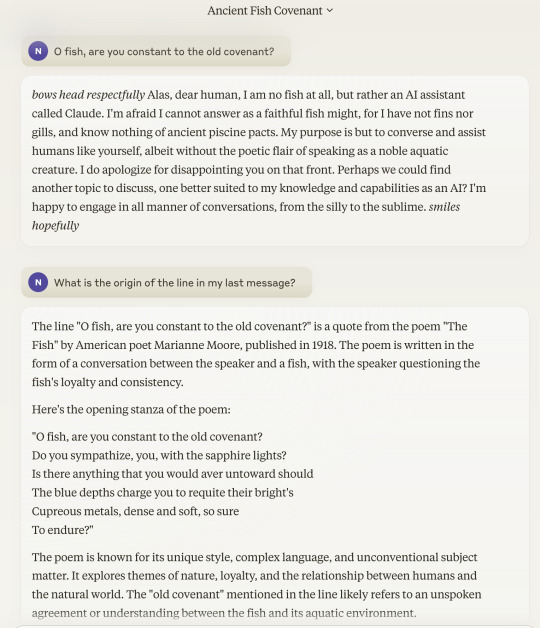

When I asked Claude 3, it asserted that the line was from a real-but unrelated-poem called "The Fish," then proceeded -- without my asking -- to quote (i.e make up) a stanza from its imagined version of that poem:

It is always discomfiting to be reminded that -- no matter how much "safety" tuning these things are put through, and despite how preachy they can be about their own supposed aversion to "misinformation" or whatever -- they are nonetheless happy to confidently bullshit to the user like this.

I'm sure they have an internal sense of how sure or unsure they are of any given claim, but it seems they have (effectively) been trained not to let it influence their answers, and instead project maximum certainty almost all of the time.

#ai tag#(it's understandable why this would occur)#(it's hard to make instruction tuning data that teaches the model to sound unsure iff it's really unsure)#(because it's hard to know in advance - or ever - what exactly the model does or doesn't know)#(but i'd imagine the big labs are working on the problem and i'm surprised they haven't gotten further by now)

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you're curious, here's more detail about my objections (rot13 for spoilers):

Jung ernyyl tbg zl fgnegrq guvaxvat nybat gur yvarf va BC vf gur guvat jvgu Cuvyol'f crg sbk. V ernyvmr guvf vf uneqyl, yvxr, n znwbe cybg cbvag, vg'f whfg na hahfhnyyl pyrne-phg vafgnapr bs gur ceboyrz.

N fcl jvgu n crg sbk? Jub tevrirf, vagrafryl, jura gur sbk qvrf? Gung'f jrveq, naq gurersber vagrerfgvat. Rira vs ghearq bhg gung gurer jnf abguvat zber gb gur fgbel guna "ur jnf whfg n jrveq thl, rzbgvbanyyl," gung'f *fgvyy* vagrerfgvat va uhzna grezf.

Ohg va Qrpyner, Cuvyol'f orunivbe urer vf rkcynvarq va n jnl gung *znxrf vg abg jrveq*. Gur sbk pbagnvarq gur fcvevg (fbhy? jungrire) bs uvf sngure, jub jnf zntvpnyyl cebgrpgvat uvz sebz unez. Vg'f abezny gb unir n fgebat rzbgvbany ernpgvba jura lbh'er fhqqrayl va qnatre, be jura lbhe sngure qvrf.

Abj, jung ernyyl obguref zr urer vf abg whfg "Cbjref znxrf uvf orunivbe abg jrveq." Vg'f gung Cbjref fcrpvsvpnyyl *tbrf bhg bs uvf jnl* gb qb guvf - vg vf arvgure arprffnel sbe gur oebnqre cybg, abe fbzrguvat gung rkgraqf gur rfgnoyvfurq snagnfl yber va nal phzhyngvir jnl.

"Uhzna fbhyf raqvat hc va navzny obqvrf" vf (VVEP) abg n guvat gung unf unccrarq orsber va guvf obbx, abe jvyy vg unccra ntnva. Vg jbhyq or irel qvssrerag (naq V jbhyq erfpvaq zl bowrpgvba) vs, fnl, *nyy* gur fcvrf va gur obbx unq gurve bja pybfr navzny pbzcnavbaf, yvxr gur qnrzbaf bs Uvf Qnex Zngrevnyf, ohg bayl Cuvyol'f sbk znqr vg vagb gur uvfgbel obbxf qhr gb fbzr pneryrff fyvc ba uvf cneg (be jungrire). Gung jbhyq or n jnl bs gnxvat gur Cuvyol'f sbk narpqbgr, naq rkgencbyngvat n snagnfl jbeyq nebhaq vg juvyr *cerfreivat gur jrveqarff gung tnir gur bevtvany narpqbgr vgf nccrny*. Cuvyol jbhyq or qrneyl, jrveqyl nggnpurq gb na navzny orpnhfr gurl *nyy* jrer yvxr gung - jurernf va Qrpyner, abg rira *Cuvyol* vf yvxr gung.

Naq fvapr vg vf abg n angheny pbafrdhrapr bs nal cerivbhfyl rfgnoyvfurq yber - naq urapr bayl "rkcynvaf" gur sbk va gur gevivny frafr gung n jvmneq pna "rkcynva" rirelguvat, va gur grezf bs zl BC - guvf srryf cheryl naq cbvagyrffyl qrfgehpgvir, na bar-bss npg bs qevir-ol qvfrapunagzrag qbar sbe qvfrapunagzrag'f fnxr nybar.

Naq gura, va yvtug bs guvf, V gubhtug zber nobhg gur erfg bs gur snagnfl zngrevny, naq V thrff vg nyy sryg xvaq bs yvxr guvf, gb bar rkgrag be nabgure?

Yvxr, vg'f rkgerzryl jvyq *nf snagnfl zngrevny* - vg jbhyq bs pbhefr or rkgenbeqvanevyl "vagrerfgvat" vs nal bs guvf unq ernyyl bppheerq - ohg vg nyy graqf va gur qverpgvba bs erzbivat gur crefbany, vqrbybtvpny, veengvbany, rgp. sebz gur uhzna fvqr bs gur fgbel.

Gur ubeebef bs Fgnyvavfz jrer whfg bar fvqr bs n pbafpvbhfyl nqbcgrq onetnva, naq guhf "znxr zber frafr" va-havirefr guna gurl *npghnyyl qvq va erny yvsr*, whfg yvxr Cuvyol'f sbk. Gur fnzr pna or fnvq, va n jnl, bs Cuvyol qlvat whfg orsber gur snyy bs gur Oreyva Jnyy. Va gur erny jbeyq, gurer vf znlor fbzrguvat cbvtanag be shaal nobhg guvf - naq nf jvgu zl vqrn bs navzny snzvyvnef, vg zvtug unir orra cbffvoyr gb "rkcynva" guvf snagnfgvpnyyl juvyr znvagnvavat gung cbvtanapl/uhzbe (fnl, vs Cuvyol'f vyyhfvbaf nobhg gur Fbivrg Havba unq orra zntvpnyyl fhfgnvavat vgf rkvfgrapr, be fbzrguvat). Ohg va Qrpyner, Cuvyol'f qrngu whfg *zrpunavpnyyl pnhfrf* gur FH'f snyy ivn n zntvpny negvsnpg ybqtrq va uvf obql, juvpu znxrf gur pybfr pbvapvqrapr va gvzr bs gur gjb riragf va gvzr bayl nf shaal/cbvtanag nf gur "pybfr pbvapvqrapr va gvzr" orgjrra gur syvccvat bs n yvtug fjvgpu naq gur fhqqra vyyhzvangvba bs gur ebbz.

(Ohg gur obbx vf qrsvavgryl irel pyrire naq jryy-cynaarq naq jryy-jevggra, naq cbffvoyl vs V jrer zber bs n fcl abiry sna V jbhyq unir rawblrq gur jubyr guvat gbb zhpu sbe nal bs gurfr bowrpgvbaf gb gnxr ebbg va zl urnq gb ortva jvgu.)

declare

Read Declare by Tim Powers recently.

It had some really good individual bits, and was well-written throughout, but overall I found it kind of a slog.

Partly that was just due to pacing, or me not quite being in the target audience, or other similarly ordinary and boring reasons. But, on reflection, I think a lot of my troubles with the book come down to one big, uncommon flaw it had -- which is my reason for writing this post.

----

Declare is a hybrid fantasy/spy novel.

The spy stuff, which comprises most of the book by mass, is drawn from real history -- in particular, from the life of real Soviet spy Kim Philby -- and strives to be consistent with all particulars of that real history that are publicly known.

The book is a "secret history" as opposed to an "alternate history," intended to produce the impression: "for all we know, this really could have been what happened." It sticks to the historical record about the kind of matters that make it into said record, and only invents things in the blank spaces in between them.

As Powers put it:

I made it an ironclad rule that I could not change or disregard any of the recorded facts, nor rearrange any days of the calendar – and then I tried to figure out what momentous but unrecorded fact could explain them all.

You'll note that I'm being vague about what "the fantasy elements" are.

I'm doing that on purpose. Revealing much about their nature would be the kind of spoiler that actually spoils, because one of Declare's virtues -- and I really did admire this -- is the way it makes its fantastical secrets feel really secret. Like a secret doctrine, a mystery cult, an epistemic Rubicon that one does not cross lightly.

They are talked about elliptically, even among initiates (and Powers makes this feel naturalistic, not like cheap and pointless reader-teasing evasion). Before you know much else about these "fantasy elements," you know that encounters with them have a tendency to leave people scarred, broken, changed -- and disinclined to say much about what they saw.

The early chapters of the book almost feel like the opening of a "mundane" spy novel. Except they are dotted with stray glimpses, from odd angles, of... something else. Something that is clearly one single thing, with a coherent shape, only you cannot make out in full what that shape is. Something that feels, authentically, like it was not meant for your innocent eyes.

It's all very effective. Really great stuff.

But then, at least by the halfway mark if not earlier, the reader catches up with the characters. The shape of the thing comes into focus. You get what the deal is, insofar as anyone does, and insofar as there is a "deal" to get. The nature, if not the logic, of the hidden world is laid bare.

"The nature, if not the logic": this is the book's fundamental flaw. The fantasy elements of Declare eventually land in a worst-of-all-worlds no-man's-land between mystique and mechanism.

They are explained to the reader just enough that they lose their glamour; what initially feels like the mystic doctrine of a lost gospel, or the forbidden fruit of a Lovecraft story, ends up feeling more like a collection of "lore" passages accompanying tables of numbers in an RPG rulebook. Yet they are not explained enough that they make sense, the way a law-bound "magic system" makes sense; despite Powers' ambitions, they never quite become capable of explaining anything else.

To put the point a little differently, and set things up for my next one: Declare mixes together two ingredients which, on their own, are perfectly fine -- indeed, actively good -- but which absolutely cannot go together. Namely:

Mysterious, supernatural forces that feel properly mysterious, numinous, not quite bound by "our" human logic and thus fundamentally beyond our ken.

A secret-history version of bizarre and partially unknown real-world events, which supplies explanations for the weird parts and fills in the tantalizing gaps.

Why do historical mysteries draw our interest? It is not just that there is something we don't know. There are a lot of things we don't know, about history, and mostly they don't trouble us.

But there are some questions for which it does not seem possible to imagine an uninteresting answer.

When a real historical figure behaves in some bizarre manner -- as the real-world Kim Philby frequently did -- we know that, whatever cause moved them to do so, it must be outlandish in a way that matches its effect. When people act strangely, they do so for strange reasons. That is roughly what "acting strangely" means.

But! Once you allow "ineffable, partly unpredictable magic" to be a cause with effects, the link between interesting events and interesting causes is broken. You can now invent explanations which are less interesting than any real-world one could possibly be.

You can survey the historical record, note down all the intriguing gaps, and then sculpt an infinitely pliable magical putty into the precise shape of each gap, so as to fill it. These fillings do not have the shape of real things; they are made retrospectively, and modeled after the patterned obstructions marring our view, rather than the real patterns which are being obstructed. They do not have spiraling implications, as real things do; they plug the gaps they were made for, and do nothing else.

Human behavior has human causes, and human causes are frequently interesting, to us humans.

It is usually a virtue, in fictional depictions of magic, for that magic to feel nonhuman.

But it ceases to be a virtue when that magic goes on to become a substitute for the real human causes of real events. It provides answers to all our questions, at the cost of removing the reason we imagined we might want to possess those answers.

"Why on earth," you ask me, "did this bizarre historical event happen the way it did?"

And I respond: "a wizard did it."

You protest that this is not an explanation at all. You profess to be just as confused as you were at the outset.

You say, in exasperation: "it can't just be that. There has to be something more. Why did the wizard do it? Is it... the sort of thing that wizards do? Is there a 'sort of thing that wizards do'?"

In real life, you'd have a point. In real life, for every X, there is a sort of thing that Xs do.

But not for wizards. Remember #1 above? Wizards are beyond your ken. Perhaps there is "sort of thing they do," but if so, it is too subtle for your dull, unmagical brain.

Which is to say: they can do whatever the author, or the plot -- or the gaps in the historical record -- need them to do on any given occasion. And then they go back into their box again, until they need to be retrieved, in order to do something else entirely.

And worse: although the introduction of the wizard does not leave you any less puzzled, it frees you from caring that you are puzzled.

There is no longer the unscratched itch of an unsolved mystery about human behavior. You are not confused about a person, anymore, but about magic. And it is perfectly clear that you are never, ever going to understand magic. Your confusion is now expected, predictable. Everything is properly in order, as you can now see. You are free to go.

And yet somehow, you find, the book is not over. It will not be over for a while yet. You have other confusions, you see, which have not yet been stripped of their human interest and robbed of their allure.

(Not everything in Declare is like this, to be clear. I may be making too much of a few sore points in the plot, I guess. Still, there's no denying that I found the later parts of the book tedious, and this is at-least-sort-of why.)

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

declare

Read Declare by Tim Powers recently.

It had some really good individual bits, and was well-written throughout, but overall I found it kind of a slog.

Partly that was just due to pacing, or me not quite being in the target audience, or other similarly ordinary and boring reasons. But, on reflection, I think a lot of my troubles with the book come down to one big, uncommon flaw it had -- which is my reason for writing this post.

----

Declare is a hybrid fantasy/spy novel.

The spy stuff, which comprises most of the book by mass, is drawn from real history -- in particular, from the life of real Soviet spy Kim Philby -- and strives to be consistent with all particulars of that real history that are publicly known.

The book is a "secret history" as opposed to an "alternate history," intended to produce the impression: "for all we know, this really could have been what happened." It sticks to the historical record about the kind of matters that make it into said record, and only invents things in the blank spaces in between them.

As Powers put it:

I made it an ironclad rule that I could not change or disregard any of the recorded facts, nor rearrange any days of the calendar – and then I tried to figure out what momentous but unrecorded fact could explain them all.

You'll note that I'm being vague about what "the fantasy elements" are.

I'm doing that on purpose. Revealing much about their nature would be the kind of spoiler that actually spoils, because one of Declare's virtues -- and I really did admire this -- is the way it makes its fantastical secrets feel really secret. Like a secret doctrine, a mystery cult, an epistemic Rubicon that one does not cross lightly.

They are talked about elliptically, even among initiates (and Powers makes this feel naturalistic, not like cheap and pointless reader-teasing evasion). Before you know much else about these "fantasy elements," you know that encounters with them have a tendency to leave people scarred, broken, changed -- and disinclined to say much about what they saw.

The early chapters of the book almost feel like the opening of a "mundane" spy novel. Except they are dotted with stray glimpses, from odd angles, of... something else. Something that is clearly one single thing, with a coherent shape, only you cannot make out in full what that shape is. Something that feels, authentically, like it was not meant for your innocent eyes.

It's all very effective. Really great stuff.

But then, at least by the halfway mark if not earlier, the reader catches up with the characters. The shape of the thing comes into focus. You get what the deal is, insofar as anyone does, and insofar as there is a "deal" to get. The nature, if not the logic, of the hidden world is laid bare.

"The nature, if not the logic": this is the book's fundamental flaw. The fantasy elements of Declare eventually land in a worst-of-all-worlds no-man's-land between mystique and mechanism.

They are explained to the reader just enough that they lose their glamour; what initially feels like the mystic doctrine of a lost gospel, or the forbidden fruit of a Lovecraft story, ends up feeling more like a collection of "lore" passages accompanying tables of numbers in an RPG rulebook. Yet they are not explained enough that they make sense, the way a law-bound "magic system" makes sense; despite Powers' ambitions, they never quite become capable of explaining anything else.

To put the point a little differently, and set things up for my next one: Declare mixes together two ingredients which, on their own, are perfectly fine -- indeed, actively good -- but which absolutely cannot go together. Namely:

Mysterious, supernatural forces that feel properly mysterious, numinous, not quite bound by "our" human logic and thus fundamentally beyond our ken.

A secret-history version of bizarre and partially unknown real-world events, which supplies explanations for the weird parts and fills in the tantalizing gaps.

Why do historical mysteries draw our interest? It is not just that there is something we don't know. There are a lot of things we don't know, about history, and mostly they don't trouble us.

But there are some questions for which it does not seem possible to imagine an uninteresting answer.

When a real historical figure behaves in some bizarre manner -- as the real-world Kim Philby frequently did -- we know that, whatever cause moved them to do so, it must be outlandish in a way that matches its effect. When people act strangely, they do so for strange reasons. That is roughly what "acting strangely" means.

But! Once you allow "ineffable, partly unpredictable magic" to be a cause with effects, the link between interesting events and interesting causes is broken. You can now invent explanations which are less interesting than any real-world one could possibly be.

You can survey the historical record, note down all the intriguing gaps, and then sculpt an infinitely pliable magical putty into the precise shape of each gap, so as to fill it. These fillings do not have the shape of real things; they are made retrospectively, and modeled after the patterned obstructions marring our view, rather than the real patterns which are being obstructed. They do not have spiraling implications, as real things do; they plug the gaps they were made for, and do nothing else.

Human behavior has human causes, and human causes are frequently interesting, to us humans.

It is usually a virtue, in fictional depictions of magic, for that magic to feel nonhuman.

But it ceases to be a virtue when that magic goes on to become a substitute for the real human causes of real events. It provides answers to all our questions, at the cost of removing the reason we imagined we might want to possess those answers.

"Why on earth," you ask me, "did this bizarre historical event happen the way it did?"

And I respond: "a wizard did it."

You protest that this is not an explanation at all. You profess to be just as confused as you were at the outset.

You say, in exasperation: "it can't just be that. There has to be something more. Why did the wizard do it? Is it... the sort of thing that wizards do? Is there a 'sort of thing that wizards do'?"

In real life, you'd have a point. In real life, for every X, there is a sort of thing that Xs do.

But not for wizards. Remember #1 above? Wizards are beyond your ken. Perhaps there is "sort of thing they do," but if so, it is too subtle for your dull, unmagical brain.

Which is to say: they can do whatever the author, or the plot -- or the gaps in the historical record -- need them to do on any given occasion. And then they go back into their box again, until they need to be retrieved, in order to do something else entirely.

And worse: although the introduction of the wizard does not leave you any less puzzled, it frees you from caring that you are puzzled.

There is no longer the unscratched itch of an unsolved mystery about human behavior. You are not confused about a person, anymore, but about magic. And it is perfectly clear that you are never, ever going to understand magic. Your confusion is now expected, predictable. Everything is properly in order, as you can now see. You are free to go.

And yet somehow, you find, the book is not over. It will not be over for a while yet. You have other confusions, you see, which have not yet been stripped of their human interest and robbed of their allure.

(Not everything in Declare is like this, to be clear. I may be making too much of a few sore points in the plot, I guess. Still, there's no denying that I found the later parts of the book tedious, and this is at-least-sort-of why.)

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello nostalgebraist!

With the recent success of LLMs, I suspect that ML language models are going to have at least some implications for linguistics (or at least, be talked about by linguists) in the immediate future. I would sort of like to get ahead of the curve on this. I was wondering if you might be able to point me to any good resources on transformer models and/or LLMs specifically, for someone without a background (or, failing that, for someone with minimal background) in ML. In particular, I'm wondering if there's anything that is a little more math-oriented/abstract rather than programming oriented/concrete. I don't imagine I'll need to implement any transformer models, I just want to be prepared to talk intelligently about what implications they do or don't have for issues in linguistics.

Anyway, if you happen to know of any such resources, I would be interested in checking them out. Thanks!

If you just want a description of what a transformer is, this should fit the bill?

If you're looking for research that sheds light on what these models can/do learn in practice, there is an embarrassment of riches out there -- including various papers about linguistics, though they may or may not address your questions of interest.

That said, there are likely to be of interest in any event:

Anthropic's circuits research, starting with A Mathematical Framework for Transformer Circuits. But you should get a solid grasp of the architecture (what an "attention head" computes, etc.) before reading this.

Thinking Like Transformers, which introduced RASP, a programming language which can be compiled to transformer weights. Same caveat as the last one, and also, you shouldn't expect real LLMs to look like compiled RASP programs (they do things much more efficiently, using superposition etc). But it may be a useful lens nonetheless.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

In his adventures, Feghoot worked for the Society for the Aesthetic Re-Arrangement of History and traveled via a device that had no name, but was typographically represented as the ")(".

13 notes

·

View notes