Text

Preservation Week 2024

Virtual Presentation

Go Violets!: The History & Conservation of NYU’s Yearbook Collection

Date & Time: Wednesday, May 1, 2024 · 11 AM - 11:45 AM EDT

Location: Virtual

RSVP: eventbrite

Event Series: NYU Libraries Preservation Week 2024

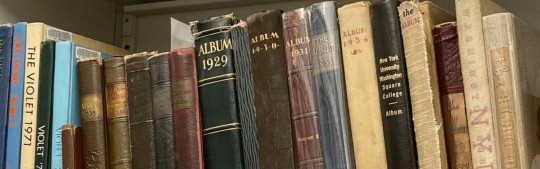

In celebration of Preservation Week 2024, the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department is hosting a virtual presentation exploring NYU Libraries’ extensive yearbook collection. The collection contains almost 1000 yearbooks dating from 1887 to 2012 issued by New York University and its component schools. It is one of the most heavily used collections in the New York University Archives. University Archivist Janet Bunde will discuss the history and use of the collection, and Special Collections Conservator Dawn Mankowski will discuss conservation treatment and her recent survey of the collection that will be used to guide our preservation priorities and ensure continued access to this important record of NYU history.

Collection Information:

https://findingaids.library.nyu.edu/archives/mc_304/

Janet Bunde (she/her) is the University Archivist in the Special Collections Department at NYU Libraries where she is dedicated to the stewardship and preservation of the collections. Janet holds a BA in history with a concentration in peace and conflict studies from Haverford College, and an MA in history with a certificate in archival administration from New York University.

Dawn Mankowski (she/her) is a Special Collections Conservator in the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department at NYU Libraries where she cares for and carries out conservation treatment on NYU’s library and archival collections. Dawn holds a BA in Art History and Anthropology from the University of Arizona, and an MA in the Conservation of Art from SUNY Buffalo State College, specializing in Library and Archives Conservation.

#PreservationWeek2024#PreservationWeek#NYULibraries#NYUSpecialCollections#librarypreservation#libraryconservation#collectionscare#paperconservation#bookconservation#preservingthepast

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peiyuan Sun's Internship Highlights

Hi, I am Peiyuan Sun (锫瑗 孙). I am a graduate student at the Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts, NYU. I have been working as a Conservation Fellow under the supervision of Preventive Conservator Jessica Pace at the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department of NYU Libraries since September 2022. Upon completion of my internship in June, I will graduate with an M.A. in Art History and M.S. in Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. In other words, by the time you see this Tumblr post, I will have finished my four-year-long studies and work! I am really grateful for working in the Department. In this Tumblr post, I will review the highlights of the past 9 months and 22 days.

Setting up a polarizing light microscope

My first mission was to build a LEICA polarizing light microscope from parts and modules. I was a little surprised at first. I had used microscopes but I had never had to build one worth thousands of dollars. And there were two manuals because the microscope would be made with parts from two different models: the stage and illuminator were from DM750 P, and the reflected light unit was DM750 M. It turned out to be straightforward and only took me and Jessica a morning to put everything together (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Me and the microscope.

The next challenge was to write instructions for beginner microscopists because both LEICA manuals assumed that their users are microscopists. To make sure that the instructions are clear to beginners in microscopy, I compiled my notes into 29 pages of step-by-step instructions with many color illustrations. The manual was printed and kept with the microscope in a binder. Not a professional microscopist myself, I found this exercise inspiring, pointing me to the large body of knowledge in microscopy that was still waiting for me to explore.

The microscope can be used in the material identification of fibers, pigments, and other particles. While other recent developments in analytical technologies made polarized light microscopy seem so primitive, a polarizing light microscope is still a beloved, simple, and powerful tool for conservators. Sometimes identification dictates how people should handle an object. For example, blue asbestos fibers are characterized by their needle-like appearance and pale blue birefringence color under transmitted cross-polarized light (fig. 2). While asbestos is an obsolete fill material with health hazard issues, they can surprisingly show up in a collection. If the fibers are loose on an object, the people handling it should take extra precautions to prevent inhaling the fibers (wearing personal protection equipment such as gloves, mask, goggles, and lab coat).

Figure 2. Blue asbestos fibers under transmitted crossed-polarized light.

Kathe Burkhard’s “Gold Fan”

The first object to treat was a painted and gilded paper folding fan made by Kathe Burkhard (1958–), an American painter, writer, and art critic. The fan is covered in gold-colored metal leaves and thick layers of transparent resin which hardened and froze the fan in its open position. Burkhard transformed a cheap paper fan into a gold fan glimmering in thick coatings that look like honey-colored amber. She wrote in white paint “truths” on the one side, and “Lies” on the other side (fig. 3).

Figure 3. The “Gold Fan” before treatment.

The fan had several issues when it came to the care of the Department. The fan’s paper leaves were torn and its gold-colored metal leaves were peeling off the paper (fig. 4). The surface was also covered with dust and grime that darkened colors.

Figure 4. Details of the torn paper fan before treatment.

With the goal to stabilize the fan and improve its appearance, we decided to close the fractures, put down the lifted metal leaves, and reduce the surface dust and grime. I used wheat starch paste to adhere to the torn edges, and I used small strong magnets to press the joints together while the starch paste dried and cured. Adhering a small part each time, I worked along each fracture, and back and forth between the two sides to make sure things align correctly. There was one tear that went along a fold line of the fan. The two sides of the tear had little overlap for adhesion, like the two halves of a malfunctioned lifted bridge. I used a strip of Japanese paper coated with starch paste and a synthetic adhesive called methylcellulose to mend this tear––now I put an extra bridge over the broken one to hold the two sides together.

I introduced gelatin solution as an adhesive to reattach the leaves to the paper. And after the leaves were secured, I used dry pre-washed cosmetic sponges to clean the surface. I cut my sponges into tiny wedges so that I can maneuver a small piece between and over fragile metal leaves. After the treatment, the fan’s paper structure was more stable, and its surface recovered some of its past glitter (fig. 5 & 6).

Figure 5. Details of the torn area after treatment.

Figure 6. The “Gold Fan” after treatment.

Rehousing objects from the David Wojnarowicz Papers MSS.092

Organizing objects crowded in a box can give conservators headaches. When I opened “box 139”, I did not know how many objects were there. It was only after taking a documenting photograph, I realized that 28 objects were crammed into one archival box (fig. 7). They are made of various materials, including metal, plastic, fabric, stone, and glass. These random things were collected by American artist David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992). Some were used as props for his photographs. For example, I noticed that a clock face, “object 092.2.0492”, with Roman numbers might be featured in his 1988 photo Untitled (Time/Money) in the Ant Series (fig. 8).

My mission is to identify the plastic objects and separate them from the rest of the objects. Apart from visual observation, I used Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to analyze materials that are suspected to be plastic. This analysis can be used as a non-destructive method. The object’s material of interest could be clamped down against the analysis window on the stage to gain data (fig. 9). Yet not all objects could be fitted onto the stage. Because the machine was intended for industrial use, where samples are usually in powder (such as drugs), the space between the stage and the built-in clamp is limited. The analysis also requires that the surface of the object be pressed against the window on the stage. The pressure can also leave tiny impression marks on some objects due to the clamping. So while the analysis may be non-destructive, it might damage the object.

Though identifying plastics with FTIR was fun, the most interesting part for me was driving a polyester encapsulation system with an ultrasonic generator and motor control. The instrument allowed me to create 35 small Mylar pockets custom-made for the objects. “Object 092.2.0504” consists of small charms (34 metal pendants and 1 feather). Before rehousing, they were stuffed in a small bag made of bubble wrap and brown pressure-sensitive tapes. After rehousing, each charm was snuggly fitted in its pocket (fig. 10). A visitor can easily see both sides of the charms by handling the Mylar sleeves.

Figure 7. Objects from the David Wojnarowicz Papers.

Figure 8. David Wojnarowicz. 1988. Untitled (Time + Money). Photographs. Gelatin silver print on paper.

Figure 9. FTIR analysis of a scarecrow candy container manufactured by the E. Rosen Company at Rosbro Plastics in the 1950s. The cardboard was added to support bigger objects on the stage.

Figure 10. Charms rehoused in Mylar pockets.

Conservation of Balinese Shadow Puppets in the Mabou Mines Archive MSS 133.

I first knew about the project of the shadow puppets from my supervisor Jessica on September 23rd, 2022. I thought it would be another rehousing project. I did not know that I would study, research, and work on the puppets till the last day of my internship. The project included research, artist interviews, treatment, and rehousing.

The 40 shadow puppets (133.2.0023 through 133.2.0053) were mostly made for MahabharANTa, written by Lee Breuer and performed in 1992 in the United States. The story is a battle between the animals and insects on the White House lawn. The puppets are flat shapes attached to wooden and bamboo handles. 6 puppets were made of paper materials, and the rest were made of painted rawhide. Balinese shadow puppet master (dalang in Balinese) I Wayan Wija made all the rawhide puppets in Bali. The puppets have fragile paints that needed consolidation. They also needed rehousing because they were originally sandwiched in flimsy paper folders and piled in two boxes.

If you are interested to learn more about his project, a recording of my presentation on the project is available through this link. Here, I want to tell you some things that are not in the treatment reports or my presentation.

An episode before everything began was taking the documentation photos of the puppets, some of which measure 26 to 28 inches long, and some have multiple moveable arms, jaws, and even antennae. Photographing colorful objects could be hard for the background color must be right. I first opted for black, the default color of the background paper already set up in the photo room. I soon realized that many puppets have black parts and all of them have dark outlines, which happily blended in with the black background. Then I tried neutral grey, a color that conservators love. The issue was that a similar grey was used on the puppets. The grey areas can be mistaken for hollow places (fig. 11). Finally, I decided to use white as my background. There was no white background paper in the photo room. Fortunately, there are plenty of white things in a book and paper conservation lab. I used a large piece of Artcare foam core as my white background (fig. 12). I regretted that I did not try different colors against just one puppet at the beginning, but caused extra handling of all puppets. Bits of paint did come off when I moved puppets around. This was a lesson learned hard.

Figure 11. Before treatment photo of the “chariot” shadow puppet against neutral grey.

Figure 12. Before treatment photo of the “chariot” shadow puppet against white.

Though I started on the project in 2022, I did not treat the rawhide puppets until 2023. Jessica and I did research into the puppets because the finding aid provided inadequate information, missing the artist and date, and whether the paper and rawhide puppets were made for the same performance. So in 2022, I treated and rehoused the paper puppets while learning about Balinese shadow puppets. Jessica and I did archival research in the Mabou Mines archives, and we found that the puppets were all made for the same performance. Two names came up as the designers of the puppets, Larry Reed and I Wayan Wija. We contact Larry Reed who told us that I Wayan Wija made all the puppets. Pak Wija lives in Bali. Our first few emails ended with no responses. When we were thinking that we would never find him, I found, on the website of the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art, an article on Balinese shadow puppet theater by Professor Lisa Gold. She met with Pak Wija and featured him in her article. I emailed her and she provided me with Pak Wija’s contact information. In February, Jessica and I interviewed Pak Wija on Whatsapp.

While the research slowed down the progress, we were grateful that we did not skip it. We learned that the Balinese puppets have sacred entities beyond their physical materials. Balinese puppets were alive in performances, needed to be fed and paid respect, and have the healing power to help people in return.

As conservators, we had limited power beyond taking care of the physical materials; Not a Balinese shadow master, or dalang, I could not take care of the spiritual parts of these puppets that I could not see or touch. According to Balinese traditions, untrained hands were not even allowed to handle sacred puppets. But Jessica and I were proud of our work. I think what we tried to do was to restore the connection between objects and people, giving back the puppets their identities and meanings. I think getting to know them is a starting point for paying the puppets the respect that is overdue so that others can do better in the future. The bond between the puppets and the people would have been lost in time and the dark storage rooms if we did not bring the puppets to Conservation.

The greatest challenge was the consolidation. To stabilize the paints, I fed an isinglass solution into detached paints to stick them back down and to hold tiny flaked paint pieces together. I chose to treat the “chariot” puppet as a trial. It took me a month to finish it. At that time, I had less than 5 months left and 29 puppets to treat and rehouse. Plus, the old stock of isinglass was running out, and I had to extract a new batch to carry on.

So finally I told Jessica, “I don’t think I can treat all the puppets.”

But the puppets might not have the chance to be treated again with enough space, time, and budget. Jessica and my colleagues said I should give it a try. The whole book and paper lab helped in making the new batch of isinglass. Jessica and I agreed that I would treat the most unstable ones as our priority. So that even if I could not treat every single puppet, the ones left would be relatively stable.

I used a Leica microscope to guide the consolidation. Examining the parts that need treatment under powerful magnification allows me to grasp the microstructures of unstable paints and find out a strategy for approaching each situation. Some look like colorful tents, volcanoes, cliffs, and archipelagoes. I found myself diminishing in size, taking a walk in these landscapes. Strangely, with the pressing deadlines, I did not feel like a desperate traveler in a hurry to get to a destination, but more like an explorer on a joyful journey.

When the final month approached, Jessica and I decided to rehouse all puppets and finish their reports before I carry out more treatment. I cut archival blue boards and cut them into the sizes of the boxes. And I attached soft Volara foam blocks as bumpers to hold the puppets in place. And Ethafoam blocks were added to the board so trays could be stacked in a box without pressing on the puppets.

Before we wrap up, Jessica and I met with Weatherly Stephan (Head of Archival Collections management) and Nicholas Martin (Curator for the Arts and Humanities) to share my research findings so that information regarding the maker, date, and correct names of the puppets can be incorporated into the finding aid. For the housing information to be updated and to facilitate clarifying “what went where”, I created a Google document with an illustrated rehousing scheme for reference. Jessica will also keep the research information, including the artists’ contacts, for future reference.

I ended with all the puppets rehoused with their own reports. Of the 37 treated puppets, 30 were consolidated. There are 3 puppets left to treat, but the amount of work required should be minimum.

Ending

I am grateful for working with so many kind and professional people during the past months. I want to give my special thanks to my supervisor Jessica Pace. Jessica helped me better understand the priorities of different tasks. This project is in debt to her patient guidance, communication, and foresight. You can also find out more about the people at NYU Libraries through the staff directory.

I want to thank any patient Tumblr reader who read thus far. If you are eager for getting into Conservation, please find out more at the Emerging Conservation Professionals Network. You are also welcome to contact me via email [email protected]. I am happy to talk about my experience and projects, or just discuss random nerdy things in Conservation.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preserving Leaf Paintings in an Anglo-Indian Commonplace Book, 1822-1825

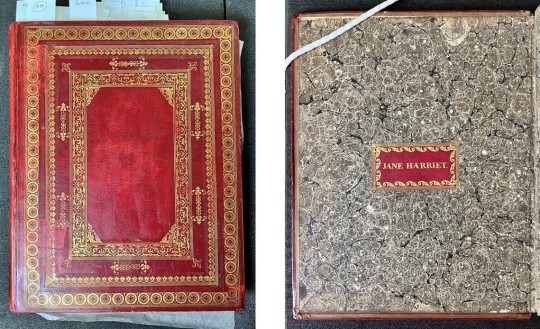

Hello, I’m Alexa Machnik, a third-year graduate student at the Conservation Center, Institute of Fine Arts, NYU. I first came to the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department in Fall 2022 as a student in the graduate course, Conservation in Context, taught by Laura McCann, Director of Preservation. During this course, we delved into the world of library conservation, exploring the value systems that guide preservation decision-making and treatment action in academic research libraries. One of my class projects involved rehousing delicate leaf paintings from an early 19th-century commonplace book, or friendship album, part of the Fales Library holdings in the Special Collections at NYU Libraries (figs. 1-2) [1]. In honor of Preservation Week, I will share the intriguing history of the book and discuss the decisions that were made to preserve the leaves.

Figure 1 [left]: Front cover of the commonplace book, bound in gold-tooled red morocco leather.

Figure 2 [right]: Ownership label of “Jane Harriet [Blechynden]” on front marbled pastedown.

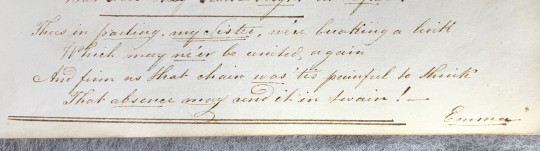

The book in question was compiled by Jane Harriet Blechynden (1806-1827) in England between 1822 and 1825. It holds her personal collection of handwritten and acquired materials, with contributions from her sisters, Emma and Sarah, who wrote original poems about sisterhood, separation, and their Anglo-Indian ancestry. The three women were the daughters of a British merchant residing in Calcutta, and while born in India, they were educated in England [2]. There is not a great deal known about Jane Harriet’s life in England, but her impending return to India in 1825 is documented in an emotional verse by Emma (fig. 3):

“Thus in parting my sister we’re breaking a link / Which may ne’er be united again / And firm as that chain was ‘tis painful to think / That absence may send it twain.”

Figure 3: Excerpt from the original poem, “Parting and a Meeting,” signed by Emma.

Jane Harriet’s book offers insights into her personhood, social connections, and sensibilities as an artist and collector. In addition to written entries, she inserted a compendium of acquired materials–pressed flowers, her own original drawings, and numerous paintings–between pages of the book (figs. 4-6).

Figures 4-6 [left to right]: A small sampling of the ephemeral treasures found in the book, including a dried pressed flower, a drawing on pith possibly by Jane Harriet, and a cut-paper silhouette.

Notably, six of these paintings are executed on the dried leaves of the Bodhi tree, a sacred plant indigenous to Asia with distinct spade-shaped, long-tipped leaves (fig. 7) [3]. Although leaf painting has origins in Buddhist traditions, by the time Jane Harriet collected her leaf paintings, it had already evolved into a form of Chinese export art in Europe. Her leaves depict secular scenes of contemporary life in China and botanical subjects, which are typical of the export genre (fig. 8). Their inclusion in the book implies that Jane was among the many people who partook in the avid collecting of China trade goods during the first few decades of the 19th century, a time when European fascination for Chinese culture and art was at its peak.

Figure 7: A leaf painting, as found loose in the book and partially lifted to show the thin, translucent nature of the leaf support.

Figure 8: Another leaf painting from the book, oriented with the leaf tip at the bottom of the image, depicting flowers and a butterfly.

The initial rush of excitement that I felt at finding the leaf paintings soon turned to concern as I gave thought to their long-term preservation at NYU Libraries, where researchers are expected to handle the book. The leaf paintings were loose in between the pages, which raised a series of “what ifs” about the potential dangers they could encounter. What if the leaves slip from the book? What if they bend or break as the pages are turned? What if the painted surfaces become abraded? The paintings were made with opaque pigment-based watercolors on exceptionally delicate, skeletonized leaves that have been primed with a thin organic coating. Despite being intact, their inherent fragility means that they are vulnerable to even the slightest touch. After considerable discussion, the Conservation Unit decided that in order for the leaf paintings to be preserved and safely accessed by researchers, they should be housed separately from the book.

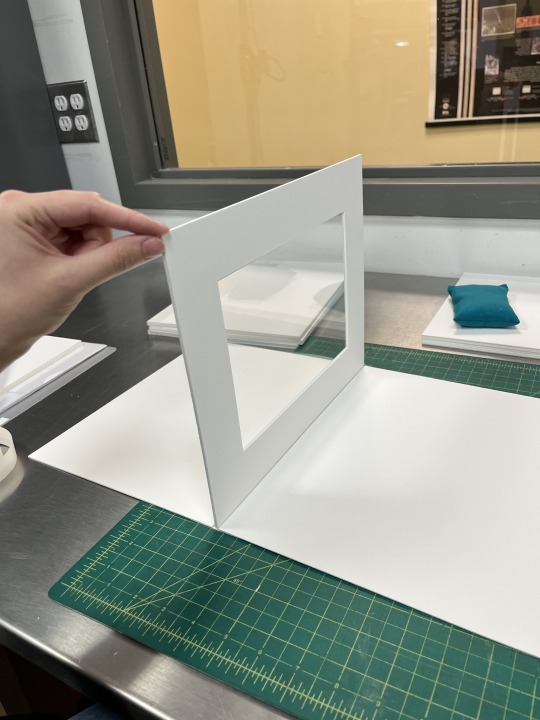

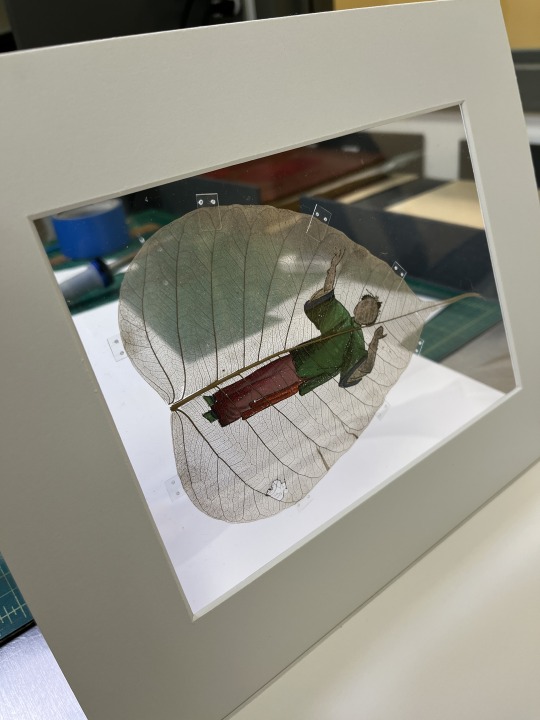

I thoroughly examined the condition of the leaves and the painted surfaces in order to make a housing recommendation. Despite some minor damage, all were in stable condition. Thus, the ideal housing would provide support to prevent any further damage, such as paint loss and leaf breakage, and at the same time allow the leaves to maintain their translucency. To achieve this, I opted to mount them in double-sided window mats with a support made from clear polyester film, or Mylar® [4]. The addition of the Mylar® would not only create a stable surface for the leaf paintings but also enable the viewing of both sides (fig. 9).

Figure 9: View of the double-sided window mat with a Mylar® support.

My next challenge was to figure out how to mount the leaves onto the Mylar® support without the use of adhesive [5]. After consulting with conservation staff and creating mock-ups, short, discreet Mylar® tabs were selected as the best option to secure them into place (figs. 10-11). For this process, I positioned a single leaf painting onto the support and selectively placed the tabs around its perimeter, making sure the tabs did not overlap any areas of paint. I then used a handheld spot-welding pen to fuse the tabs to the support. Since this process was done in-situ, near the leaf, it required lots of precision practice and encouragement from colleagues before I felt confident enough for the task.

Figure 10: Detail of a mounted leaf painting. Notice that the Mylar® tabs are welded just outside the leaf and extend minimally over the edges, holding it in place with gentle pressure.

Figure 11: The backside of a mounted leaf painting viewed through the Mylar® support. This gives researchers access to the painting’s verso, where an underdrawing and other signs of artistic process can be discerned.

At the time of writing this post, I successfully housed the six leaf paintings in their double-sided window mats (figs. 12-13). This housing project, while complete, is just one part of the ongoing effort to preserve the commonplace book, and the Conservation Unit is continuing work on other elements of the book to ensure its safe return to Special Collections.

Figure 12: Example of the completed housing, showing the front of a leaf painting.

Figure 13: Back of a leaf painting.

Though my involvement in the project has come to an end, I have gained a very special appreciation for the commonplace book and the preservation challenges it presents. The experience of learning directly from NYU Libraries Special Collections was especially invaluable, providing me with opportunities to participate in complex decision-making processes unique to large research libraries driven by user needs. Before signing off, I’d like to extend my gratitude to my supervisors, Laura McCann, Director, and Lindsey Tyne, Conservation Librarian, and the entire team at the Barbara Goldsmith Conservation Lab for their unwavering support and enthusiasm throughout this project. Thank you all very much!

Notes:

[1] A commonplace book is a centralized place for an individual to record information, whether it be their personal thoughts or quotes from outside literary sources. Friendship albums, by contrast, contain handwritten entries from the family, friends, or acquaintances of the owner (often female). Both forms of commonplacing sustained popularity in Europe and America throughout the 19th century. To learn more about this fascinating literary genre, see Jenifer Blouin, “Eternal Perspectives in Nineteenth-Century Friendship Albums,” The Hilltop Review, Vol. 9, Issue 1 (2016) and Victoria E. Burke, “Recent Studies in Commonplace Books,” English Literary Renaissance, Vol. 43, No. 1 (2013), 153-177.

[2] Much of what is known about Jane Harriet (also known in her family as Harriet) comes from the Blechynden papers in the British Library (Add. Mss. 45578-663). This large holding contains the diaries of her father, Richard (Add. Mss. 45581-653), and older brother, Arthur (Add. Mss. 45654-61). For a secondary account of the Blechynden household, see Peter Robb, Sentiment and Self: Richard Blechynden’s Calcutta Diaries, 1791-1822 (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[3] Michele Matteini, “Written on a Bodhi tree leaf,” Anthropology and Aesthetics, Vol. 75-76 (2021), 45-58.

[4] The design of the double-sided mats is based on an instructional guide made available by the Library of Congress. “Double-Sided Mat,” Library of Congress, accessed 1 February 2023.

[5] We chose not to use adhesives or traditional paper-hinging techniques to mount the leaf paintings for several reasons. As noted, the paintings are on fragile, non-paper-based supports that have an organic coating, which may be derived from plant gum. The leaf supports are thin, translucent, and highly vulnerable to breakage, so applying hinges directly with adhesive might permanently alter their appearance or risk further damage to the leaves over time, especially if they need to be removed from the housing in the future.

Photographs: Alexa Machnik

#NYULibraries#NYUSpecialCollections#FalesLibrary#nyuifa#nyuart#librarypreservation#libraryconservation#collectionscare#artconservation#paperconservation#bookconservation#artpreservation#preservingthepast#PreservationWeek#preservationweek2023

208 notes

·

View notes

Text

FILM INSPECTION: THE EARLY FILMS OF BETH B

by Emily Jenne, Institute of Fine Arts Conservation Center graduate student

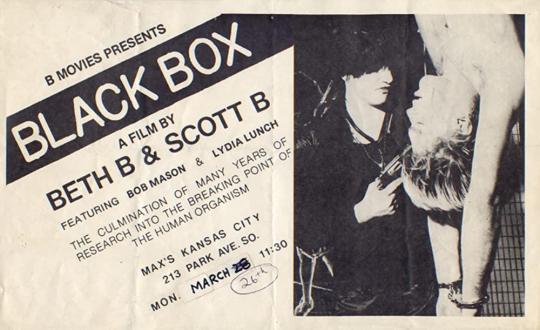

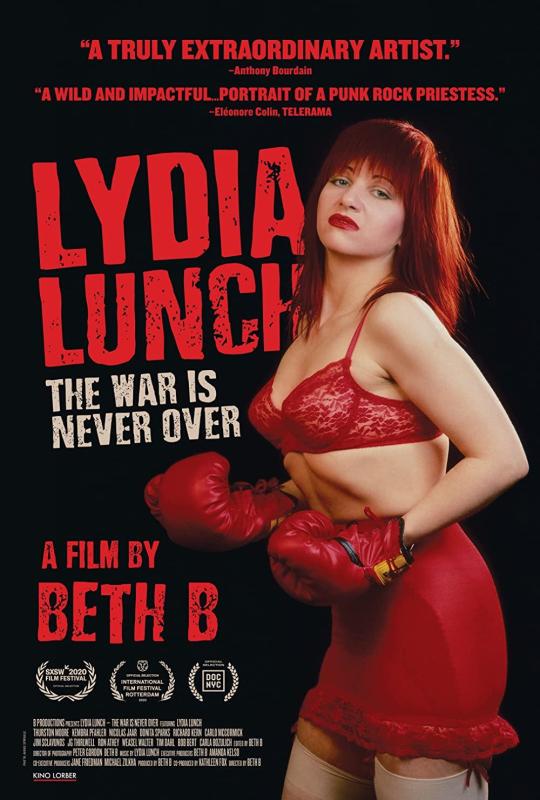

Beth B, one of the most influential filmmakers to emerge from the generative chaos of the 1980s downtown scene, is known for her transgressive head-on confrontation of power structures and sexual politics. She formed the independent film production company B Movies (a play on low-budget films) with her partner Scott B, with whom she has worked over the years along with a panoply of collaborators, downtown luminaries such as Jack Smith, Arto Lindsay, Pat Place, John Lurie, Bill Rice, Gary Indiana, James Nares, Kiki Smith, Tom Otterness, Richard Edson, Vivienne Dick, James Russo, Richard Prince, Ann Magnuson, Jenny Holzer, Richard Kern, Kembra Pfahler, James Habacker, Dirty Martini, Thurston Moore, and Kai Eric (the list goes on). She is still active today, and her recent documentaries zero in on burlesque, no-wave provocateur Lydia Lunch, and the painter Ida Applebroog (who also happens to be Beth B’s mother).

Flyer for ‘Black Box’

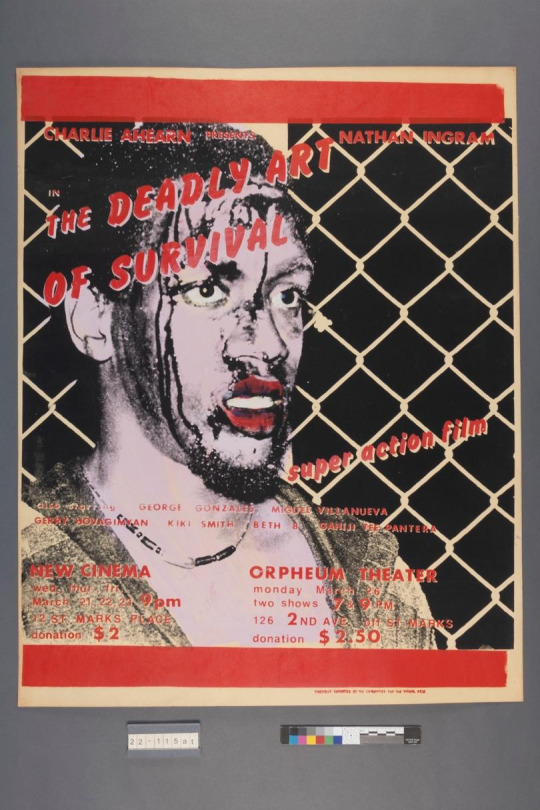

As a longtime Beth B fan myself, I was thrilled to have the opportunity to work on several of her early films as they entered NYU’s Special Collection (Beth B Papers, MSS.614; Scott and Beth B (B Movies) Records, MSS.622). This included: G Man (1978), Black Box (1979), The Trap Door (1981), Salvation (1987), Belladonna (1989), and Visiting Desire (1996), as well as a copy of Un Chant d’Amour (1950) the first and last film by French writer Jean Genet, famously banned for its explicit content. As a graduate student specializing in both time-based media and paper conservation at the Institute of Fine Arts NYU, I am often asked where these two seemingly disparate fields overlap. The work I’ve done at the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department is an excellent example of the two working in tandem. The Beth B collection, for example, has both a media component (the films) and an accompanying paper element (posters and other ephemera).

‘The Deadly Art of Survival’ poster, photograph by Dawn Manokowski

Film preservation begins with an assessment logging current conditions and identifying the media, which will determine the best practices for storage. The first order of business is identifying the film base as cellulose nitrate, acetate, or polyester. The film gauges present in the Beth B collection, 16mm and Super 8mm, ruled out one possibility, cellulose nitrate which was never used as an 8mm or 16mm substrate in the West. From there, acetate and polyester could be distinguished using a very high-tech piece of equipment, 3D movie glasses. A pair of polarized 3D glasses folded in half at the nose can be used for a polarization test. When slid between the lenses, a polyester base will birefringe, acetate will not (birefringence is a phenomenon of optical anisotropy in certain materials that causes distinctive visual undulations at changing angles). In the end, all of the films were found to have an acetate base.

The film inspection bench in the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department.

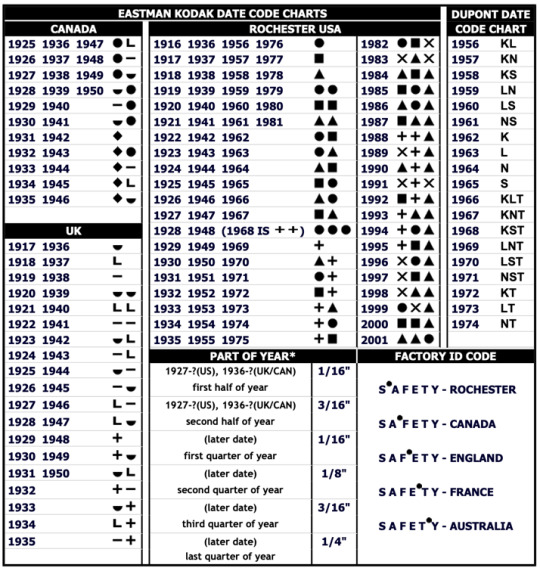

Further information about the film stock can be determined from clues in the edge code. Using a loupe and cross-referencing with an edge code chart, the year and even the location of manufacture can be established. The placement of a dot within the word ‘safety’ notes the location (acetate film base is known as ‘safety film’ in contrast to its highly reactive and flammable predecessor, cellulose nitrate). The film stock in the Beth B collection was manufactured in Rochester, NY.

Kodak edge code identifying Rochester, NY as the manufacturing location.

Eastman Kodak Date Code Chart

Information on the soundtrack format was also noted, the Super 8mm reversal films had a magnetic soundtrack, and the 16mm reversal films had a variable density optical track. Other relevant information was also recorded such as instances of surface abrasion, broken sprocket holes, number and character of splices, and any annotations on the head or tail leader (often instructions for the projectionist).

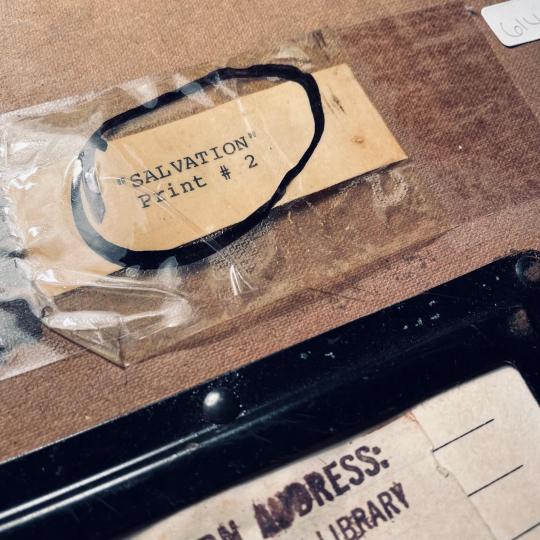

‘Salvation’ Print # 2

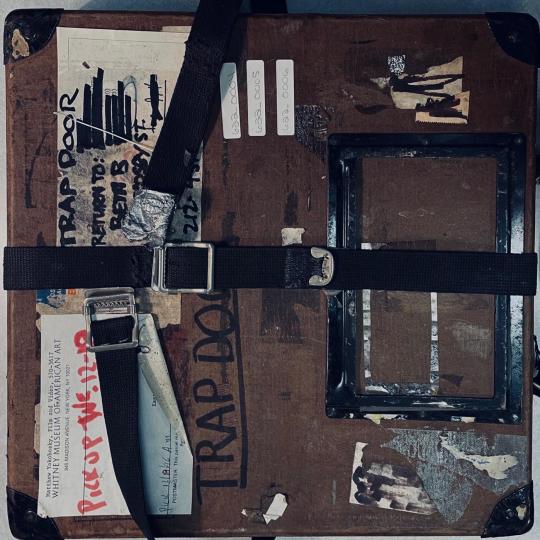

‘The Trap Door’ 8mm reel.

The major concern with acetate film base is deacetylation, an irreversible form of deterioration colloquially known as ‘vinegar syndrome’ for its distinctive acidic odor which can be detected at concentrations as low as 1 ppm. Deacetylation is essentially a reversal of the synthesis steps used to make the acetate base, and the reaction produces acetic acid which can also have a detrimental effect on the other component layers of the film. Acetic acid can soften the gelatin emulsion layer and accelerate fading of color dyes in color film. Deacetylation also leads to warpage, embrittlement, channeling, and shrinkage of the film base by as much as 10%. Shrinkage beyond 0.8% makes it dangerous to project the film.

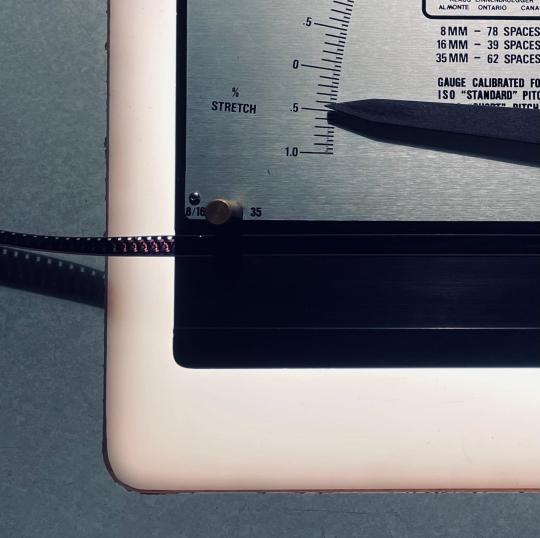

Film shrinkage gauge.

Deacetylation is exacerbated by high humidity and fluctuations in temperature, but further damage can be mitigated with correct storage conditions. The industry standard for measuring the extent of deacetylation is with AD strips, a type of targeted litmus test, which measures acidity on a scale of 0 (blue, indicating no deterioration) to 3 (yellow, which indicates critical condition). In conjunction, multiple readings taken with a film shrinkage gauge can be used to determine the average shrinkage level of the film.

An 8mm film splicer in action.

‘Trap Door’ film reel storage case.

The films in the Beth B collection were found to be in generally good condition, and minor preservation interventions included the removal of tape residue and splicing of new labeled extensions onto the existing head and tail leader. The copy of Un Chant d’Amour, now upwards of 70 years old and suffering more from the effects of deacetylation in contrast the Beth B films, is a good reminder of the importance of consistent low humidity, low-temperature storage in prolonging the life of acetate-based films, just the kind that these films will receive in their new home at NYU.

Film Poster for ‘Lydia Lunch: The War is Never Over’

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preserving the Shael Shapiro Papers

by Josephine Jenks, Institute of Fine Arts Conservation Center graduate student

Shael Shapiro is an architect best known for designing and helping to legalize live/work loft spaces for artists in downtown Manhattan. Shapiro was born in Brooklyn and studied architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, NY. In 1967, he moved into George Maciunas’ original “Fluxhouse”–an industrial loft building turned artists’ cooperative at 80 Wooster Street in the SoHo neighborhood of Manhattan. It was there that Shapiro “helped mastermind the first conversion of an industrial loft building to residential use.” (Rosenblum 2012). By 1971, several hundred artists were living and working in SoHo lofts, in violation of the city’s zoning laws. That same year, Shapiro played a major role in the writing and ratification of New York’s “Loft Law,” which changed zoning rules to legalize residential use of the SoHo loft spaces.

After the passage of the Loft Law, Shapiro spent the seventies shaping “the transformation of hundreds of dilapidated loft buildings in Lower Manhattan” (Rosenblum 2012). During the fifties and sixties, SoHo had become an economically depressed neighborhood of mostly-vacant, fire-prone commercial buildings. Known as “Hell’s Hundred Acres,” the area was slated for destructive re-development projects like a ten-lane highway proposed by Robert Moses. Shapiro, along with other members of his creative community, fought to preserve SoHo’s identity as a rich site of artistic and cultural production.

The New York University Libraries Special Collections hold hundreds of Shapiro’s architectural drawings and plans. Some were drafted by hand on tracing paper, some are printed on paper or sheets of transparent plastic, and others are duplicates that were made using early copying technologies, such as diazotypes.

Many of the Shael Shapiro drawings were folded or rolled up for several years; some are torn and tattered around the edges. In an effort to expand access to and preserve the condition of these documents, the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department is undertaking their treatment, rehousing, and potential digitization. The first step of this process is a survey that gathers information about each drawing’s size, materials, content, and condition. Next, the drawings will be sent to the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) in Philadelphia for treatment.

Already during the survey, we’ve come across drawings of New York landmarks like the Singer Building, Keens Steakhouse, and Studio 54. It’s been a pleasure to see so much of the city’s architectural history reflected in these drawings, and we’re looking forward to the day when they are safely rehoused and accessible to researchers.

Resources

Bernstein, Roslyn and Shael Shapiro. “George Maciunas: The Father of SoHo.” The Gotham Center for New York City History. May 17, 2011. https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/george-maciunas-the-father-of-soho

“City Drafts Plan for Lofts in SoHo.” New York Times, January 11, 1971. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/01/11/archives/city-drafts-plan-for-lofts-in-soho-calls-for-legalizing-artists.html

“Guide to the Shael Shapiro Papers.” New York University Archival Collections. http://dlib.nyu.edu/findingaids/html/fales/mss_200/bioghist.html

Rosenblum, Constance. “Less Familiar, but Still a SoHo Presence.” New York Times, December 28, 2012. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/30/realestate/shael-shapiro-guiding-sohos-transformation.html

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preservation Week 2023

Virtual Presentation: Conservation of Balinese Shadow Puppets from the Mabou Mines Archives

Date: Tuesday, May 2, 2023, 1:00 - 2:00 PM (EST)

Location: Virtual Event/Zoom

Registration: https://nyu_preservation_week_2023.eventbrite.com

Image: a Balinese shadow puppet from the Mabou Mines Archive, NYU Special Collections.

Since last November, Conservation Center student Peiyuan Sun has been conducting research and conservation treatment on a group of Balinese shadow puppets from the Mabou Mines Archive (MSS.133). In this presentation, she will talk about the information that she has discovered regarding the history and manufacture of these materials and the ways in which she is actively working to make these items more accessible to future users.

Peiyuan Sun received her B.A. in Art History from NYU in 2018. She is in her final year at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, where she is a candidate for an M.A. in Art History and M.S. in Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. Since fall 2022, Peiyuan has been working as an Andrew Mellon Fellow at the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation and Conservation Department for her curriculum internship under the supervision of Preventive Conservator Jessica Pace.

This event is presented in celebration of Preservation Week, an annual initiative of the American Library Association aimed at connecting our communities through events, activities, and resources that highlight what we can do, individually and together, to preserve our personal and shared collections.

#PreservationWeek2023#PreservationWeek#NYULibraries#NYUSpecialCollections#FalesLibrary#nyuifa#nyuart#librarypreservation#libraryconservation#collectionscare#artconservation#artpreservation#preservingthepast

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preservation Week 2022 Recordings

For those of you who were unable to attend the two Preservation Week events in late April, here are links to the two Zoom video recordings.

Preserving and Digitizing Large Banners From The Archives of Irish America

Tues, April 26, 2022

Link to recording

Working with Glucksman Ireland House, Preservation recently received funding from the Irish Government to begin conservation assessment and rehousing of county banners from the Archives of Irish America. Come hear Preventive Conservator Jessica Pace and Digital Content Manager Michael Stasiak discuss this cross-departmental collaboration, including the DLTS project to make these large banners accessible via high-resolution digital images and photogrammetry.

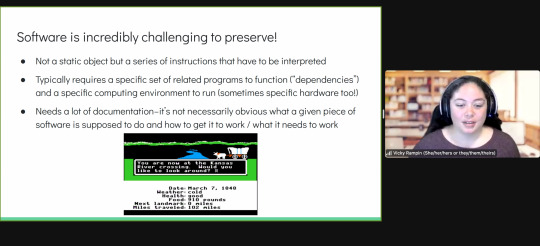

Software Preservation For Research

Wednesday, April 27, 2022

Link to recording

Join Vicky Rampin, Librarian for Research Data Management and Reproducibility, Tayla Cooper, Software Curation Specialist, and Kim Tarr, Assistant Director for Media Preservation, for a conversation about software preservation and why it's a necessary part of making research reproducible over time. Vicky and Talya will update us on one of their projects, Collaborating on Software Archiving for Institutions (CoSAI). No specialized knowledge required!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film Inspection in the Media Preservation Unit by Lindsay Miller

Hello there - my name is Lindsay Miller and I am a second-year graduate student in NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation (MIAP) program. This semester I have the privilege of working in the Media Preservation Unit at the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department, and today I will be telling you more about the work I have been doing inspecting films from collections held by Fales Library.

My first year of the MIAP program was spent entirely online, so I missed out on a lot of hands-on training. I was born in the latter part of the 1990s and do not have much recollection of older audiovisual formats except audiocassette tapes and VHS. All of my previous film production experiences were also entirely done digitally, so analog film always felt just outside of my comfort zone. I had never even been inside a projection booth until last summer when I took a tour of Cornell Cinema. Needless to say, I jumped at the chance to work in the Preservation Department at Bobst Library, as I would finally have this opportunity.

The author trying to act candid in Cornell Cinema

Let me walk you through a typical film inspection: I’ve worked with a variety of gauges throughout the semester, but my absolute favorite to work with is 35mm. Besides the fact that rewinding gives me a great arm workout, 35mm’s size allowed me to get comfortable with some basic tasks like measuring shrinkage before moving on to smaller formats, almost like training wheels.

I begin each new reel with a brief visual inspection. I’m looking for anything that seems out of the ordinary: mold, dust, debris. I will also take a look at the reel’s housing and make any notes or annotations that may be on the container. These notes can sometimes provide clues as to what is on the film and are other times just chicken scratch. A valuable skill they don’t teach you in film preservation school is how to decipher cursive handwriting!

If the reel is looking okay, I will then put it on a rewind crank to begin a more in-depth inspection. This process starts with splicing the leader onto the head of the reel, which is then labeled with its associated metadata. Then I begin to slowly wind through the film. There are some rudimentary things to look for with every inspection. Is this a black and white film or is it color? Is this a positive image or a negative? Is there a soundtrack? Most of the film I have inspected so far has not had a soundtrack, so it’s always fun when an optical soundtrack makes an appearance.

Example of a negative film print

Shu Lea Cheang Papers (MSS.381)

A wild optical soundtrack appears!

Alan Sondheim Papers (MSS.267)

Another thing to look for on film is an edge code. This is a special code printed on the edge of a film that can be used to figure out when the film was manufactured and by whom. Sometimes the answer to this will be obvious; Kodak is pretty in-your-face with its film stock and has a well-documented key that is used to decipher each symbol. Other times there is no edge code and it is up to other clues, such as a film’s housing, to determine these factors.

Kodak film manufactured in 1971

Alan Sondheim Papers (MSS.267)

During this process, I am also keeping track of any splices I may notice and will also repair them as needed. Splicing film is something that I have grown to love, even when I am working with Super8, which can be tricky to work with. It takes a steady hand and some patience to get it right but there is nothing more satisfying than repairing a bad tape splice.

Now that’s a bad splice! 35mm film

Once I finish winding through a film, I attach a leader to the tail end and wind it onto a new core. Winding film is another skill that takes practice, even though it may seem simple. It is important to keep a constant speed so that tension is evenly distributed throughout and the pack remains smooth. If a film has not been properly wound and strands stick out, it is more likely to warp or become damaged down the road. And like I said, winding 35mm is a workout! I’m always sweating by the end.

35mm rewind I was particularly proud of…so smooth!

My favorite part of working in the Media Preservation Unit has been discovering what’s contained within each collection. Every day brings about new discoveries and I love learning more about the folks behind the work. Inspecting films has also been a welcome escape from the stresses of everyday life. I love being able to sit and focus on a reel for an hour or two. Each presents its own unique challenges and it’s been a gratifying experience working with my supervisors to tackle each.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inspecting Films from the Sarah Jacobson Papers by Ana Salas

Fig. 1, Still photograph of MSS157_009

My time at Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department in NYU Libraries started in the fall of 2021 when I joined the team as an intern. My work as an intern involved a variety of tasks, but I primarily worked with films in the Sarah Jacobson Papers (MSS.157), which is a collection held in the Fales Library & Special Collections. Sarah Jacobson was an American filmmaker and a leader of the DIY movement in the 1990s. She produced and distributed her own films; with her mom, she founded Station Wagon Productions and toured the country, promoting her work and screening her films at film festivals. Jacobson passed away in 2004 after a battle with cancer, but her legacy lives on through her films.

The Jacobson films I worked on are an accretion to the Sarah Jacobson Papers collection held by Fales Library. The accretion consists of twenty-nine 16mm and Super 8mm reels, totaling some 3700ft of film. Some of these films were never developed, so I did not inspect them since light exposure would have destroyed the latent image and ruined the films. 16mm film was initially marketed for use in education and industrial films but eventually made its way into amateur filmmaking, but Super 8 was always marketed to home movie making and amateur filmmakers. The films are a mix of black and white and color, mostly shot on Kodak reversal film. Reversal film does not create a negative film element; the roll of film going through the camera is processed and becomes a positive image, which can be projected itself without printing to a second piece of film.

Fig. 2, Still from “Road Movie or What I Learned in a Buick Station Wagon”

My job was to inspect, repair, and enhance descriptions of the films in order to gain an understanding of the content and decide what should be done with the materials. The content of Jacobson’s films varied but included mainly road trips through the US and Canada, potentially trips Jacobson took to showcase her work. I also recorded information on the physical condition of the films.

Fig. 3, 16mm film spliced with tape.

Most of the Jacobson films were in good condition, but many had been edited with paper tape. Over time, the tape became gooey, and as I removed it it left a sticky residue. To remove the glue residue, I used isopropyl alcohol and cotton swabs and gently worked the glue off the films. This was a time-consuming but necessary process because it allowed me to replace the old tape with splicing tape and finish winding through the films. I also repaired any tears and damage I found along the way. Once inspected, the films were moved to 3” archival cores and vented archival cans. In addition to making repairs and removing the tape, I added a leader to the films to prepare them for scanning.

Fig. 4, Left: Torn Super 8mm film held together by tape. Right: Torn film repaired using splicing tape.

By the time my internship ended in December of 2021, I had inspected all of the 16mm and Super 8mm films and had successfully rehoused all the 16mm films. I was unable to add leader to the Super 8mm films because we found the Super 8 leader that we had on hand had shrunk over time. Putting the shrunken leader onto the splicer caused the perforations to stretch and sometimes break, so we needed to purchase a new supply of Super 8 leader. Luckily, I returned as a Media Preservation Graduate Assistant in January of 2022 and was able to finish adding leader and rehousing these films. Because some of the films were undeveloped, the archive will have to determine what to do with those films. I had the opportunity to scan some of the films and create access copies so that researchers and curators can get a better understanding of the content in the accretion. The work I did with the Sarah Jacobson films was rewarding and helped me develop my inspection and film handling skills. Today, the Sarah Jacobson films sit safely in our vault awaiting the next step in their journey.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

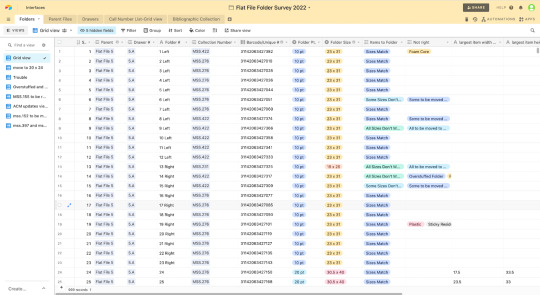

Surveying oversized materials in the Special Collections

I’m Maddie DeLaere, a graduate student preservation intern at NYU’s Special Collections Libraries this semester. I am working toward master's degrees in Food Studies and Library Science at NYU and LIU focusing on history, culture, archives, and special collections. Through the dual-degree program, I got set up working in the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department.

The Special Collections Libraries are undergoing an incredible renovation, and with the completion of some spaces approaching soon, a lot of material is going to be moved around. We are getting new flat file cases for the newly renovated space since many of ours have sticky drawers, broken hardware, or are unnecessarily bulky. A renovation is a great opportunity to assess materials in their current condition and do some rehousing projects. These flat file cases are prone to becoming miscellaneous drawers. Not the kind of junk drawers your collection of business cards and unused takeout silverware and spare change goes into, but one with unprocessed, loose, or difficultly-sized materials. Sometimes you don’t know just where to put things, and don’t have time to figure it out — it seems, that’s where the flat files have come in handy.

But no longer! This semester, I’ve been assigned a housing survey project in order to assess our oversized flat file material before the renovation move. This way, the use of the new space can be planned according to the needs of the material, not necessarily based on the way they’re currently housed. In developing and implementing the survey on AirTable, we’re able to analyze data in various ways, ultimately organizing priority levels for remedial work.

When designing the survey, we needed our end goals in mind. We want to minimize the use of our flat file storage in order to maximize our use of new space. So, we want to flag any material that doesn’t fit within its folder, or within the flat file whether too big or too small. This is done not only to minimize use of the flat files, but also to ensure that material is not harmed in the moving process. Material is kept safe during handling when it is fitted correctly to its folder. Simply measuring each item within each folder would make for a meticulous, messy, and excessively detailed survey, requiring much more data crunching and analytics down the line. To make the survey more efficient and effective, we decided to assess whether material was either A. too small for the flat files (defined as being able to fit into a 20 x 24 archival box), B. too large for its folder (sticking out from the edges or folded to fit), or C. sized correctly for its folder and the flat file. The largest item was measured in each full sized folder (36 x 48) in order to grasp what size of new flat files would be necessary

In addition to measuring size, the survey was an opportunity to collect other sorts of data. Some of this material has not had eyes on it since it was originally housed, so it’s important to take advantage of someone already going through every folder. We recorded identification (barcode, collection number, etc.) for easy updating in the system should rehousing be necessary, folder paper thickness and size, and flagged any items with unique characteristics such as being plastic, glass, cloth, framed, foam core, heavy, and unlabeled or loose. Other risk assessment was taken into account and could be recorded in the “notes” section of the survey, to alert supervisors of potential mold, pests, sticky residue, an overstuffed folder, rusty paperclips, if an item was fragile and crumbling, etc.

After surveying a thousand folders in the six flat file cases kept on floor 3 (we have even more on floor 10!) it was time to break and start some remedial work. The first remedial work we want to be done is whatever is the fastest and easiest path to discarding an entire flat file (less to move, other remedial work can potentially be done after the move). By consolidating unprocessed materials, de-duping unprocessed materials, and rehousing folders where all material can be moved to a 20 x 24 archival box, we can free up adequate space in drawers for other material. This work involves labeling new folders, moving barcodes, and updating both our AirTable survey and our ArchiveSpace records.

The survey has been a great glimpse into the way materials are accessioned and processed, the communication between the Preservation/Conservation and Archival Collections Management (ACM) departments, the preventative maintenance of a collection, and the steps taken to remediation. I was exposed to all sorts of troubles you can run into while working with special collections materials like space access, brittle material, needing buffering interleaving paper, or dealing with loose materials without an associated collection. Oversized materials pose issues of their own. Our largest flat file folders are 36 x 48 in. When those are heavy or overstuffed, it becomes difficult to handle safely as one person. And all in the middle of renovation construction with dust, humidity, and space management concerns!

Part of what is so special about working within the Special Collections Libraries is even while you’re at times doing meticulous or monotonous work, it is never boring. The material you’re working with is indeed special.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Testing new environmental dataloggers: Pt. 1

Happy Preservation Week!

My name is Erin Fitterer and I am a third-year student at the Conservation Center at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, with a focus on objects and time-based media. Though I am now focusing on other materials, much of my pre-program experience before attending NYU was actually in paper conservation, and I’m excited to be able to work in a library again. This semester, I am working with Jessica Pace on a project involving the dataloggers used by the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation and Conservation Department to monitor collections storage spaces at Bobst Library.

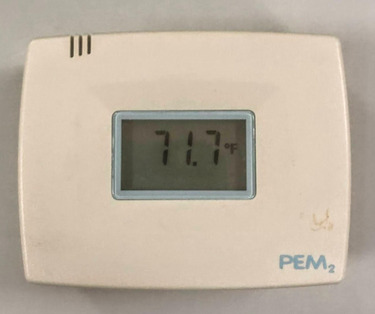

Dataloggers are an important tool when it comes to the care of collections. A datalogger is a device that records data about its surroundings at a regular interval, allowing conservators to monitor the environment of a given room or area over a long period of time. Depending on how they are made, a datalogger can record a wide range of information about a space, including monitoring vibrations and light levels. As conservators, we are most interested in monitoring the temperature and humidity levels in locations where collections are stored. Previously, conservators from the Preservation Department have been using PEM2 dataloggers. These devices monitor both temperature and relative humidity. To access the data, a USB device must be inserted into each logger. Unfortunately, the PEM2 device is no longer being supported by its manufacturer. To ensure continued access to loggers that can be calibrated and updated, we set out to find a replacement.

The first step for replacing PEM2 dataloggers was research. We wanted to find a datalogger that was able to record similar information as the PEM2 devices (namely relative humidity and temperature). Technology has changed since the introduction of the PEM2 to the market. While being able to capture the data from each device with a USB is a straightforward process, newer models enable the data to be accessed via the library’s WiFi network from any computer without needing to go to the location of each datalogger. This would allow our staff to monitor the collection in real-time, without needing to physically access each device.

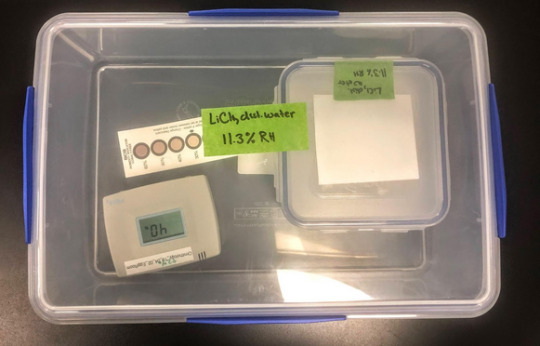

When considering what we wanted in our new dataloggers, we looked for loggers that met several criteria, including: wireless capability, unlimited software storage, visible display, and the ability to send alarms to our computer/phone. Ultimately, we decided to test out: Dickson DWE DicksonOne Display, Lascar High Accuracy Wi-Fi (no picture yet as we are waiting for it to arrive), and WirelessTag. These loggers, with exception of the WirelessTag (which has no display) met all of the criteria that we had listed above. During testing, we will be evaluating the type of power source of the datalogger (whether it needed to be plugged in or not, the average battery life, and so forth), the accuracy of the recorded temperature and relative humidity, and the ease of use of both the loggers and their software.

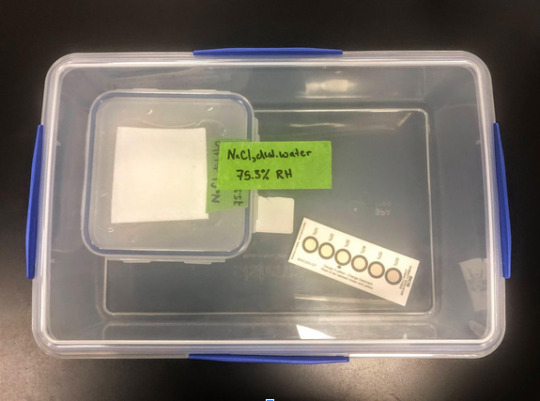

We decided to use saturated salt chambers to test the accuracy of loggers’ ability to detect relative humidity because each type of saturated salt solution has its own relative humidity (you can see a table documenting each relative humidity for its respective salt here). There are a number of recorded relative humidities for saturated salt solutions. We chose three salts for our testing chambers: sodium chloride (NaCl), RH 75.3%; magnesium chloride (MgCl), RH 32.8%; lithium chloride (LiCl), RH 11.3% . These three salts represent a broad range of relative humidities that will allow us to see how the devices perform under a range of conditions. To create the saturated salt solution testing chambers, we followed instructions posted on the Conservation Wiki written by Samantha Alderson and Rachael Perkins Arenstein. The lithium chloride and magnesium chloride were purchased from a chemical supply company. For the sodium chloride, we used Kosher sea salt purchased at a nearby grocery store. To create the chambers, we cut windows into three plastic food storage containers. Over each window, we taped a piece of Gortex.

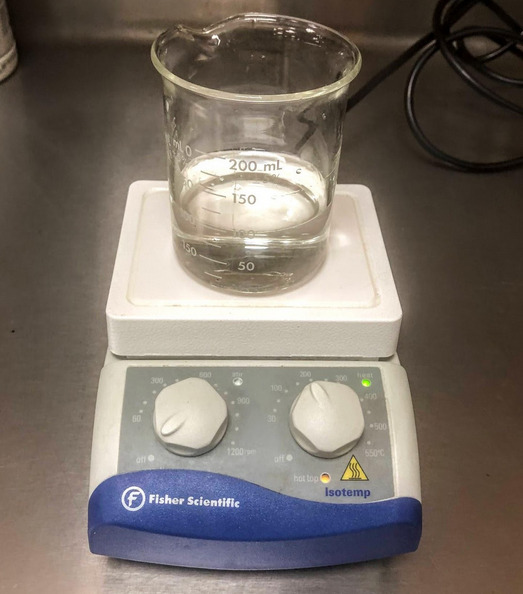

To prepare the salt solutions, we researched how much salt needed to be added to the water in order to create a saturated salt solution. We found a few publications that provided the ratios of water to salt used to achieve a saturated salt solution. Using these publications as a guide, for each salt solution, we measured 100 mL of water into a beaker. This water was heated on a hot plate, though not allowed to boil. For each of the salt solutions, salt was slowly added and allowed to dissolve. Once dissolved, more salt was added to the solution. Once the salt no longer dissolved (that is, it appeared on the bottom of the beaker), the solution was removed from the heat and allowed to cool. The result was a thick slurry mixture that was subsequently poured into the plastic food storage container. Each container and its salt solution were placed in a larger air-tight container. Within these larger containers, the datalogger devices will be placed. We will provide an update once we complete our testing.

5 notes

·

View notes

Link

Conservation Librarian

New York University: NYU - NY: Division of Libraries

Location: New York

Open Date: Mar 10, 2022

Description

New York University Libraries is seeking a Conservation Librarian, a tenure-track faculty position that supervises the library and archives conservation program for NYU Libraries Special Collections and supports the administration of the general collection care program. As a member of the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department, this position reports to the Director of Preservation & Conservation and operates in close coordination with the staff of Special Collections, Knowledge Access and Resource Management Services (KARMS), Digital Library Technology Services (DLTS), and Collections and Content Services (CCS). This individual will collaborate with their colleagues in the Media Preservation and Preventive Conservation Units to promote the long-term preservation of NYU Libraries' collections and to support the research and scholarship of the NYU community and others.

The Conservation Librarian manages the day-to-day operations of the Barbara Goldsmith Book and Paper Laboratory located in Bobst Library. They directly supervise the Special Collections Conservator and the Senior Special Collections Conservator, Fellows, project conservators, and student employees. The Conservation Librarian indirectly supervises the Commercial Binding Specialist, who reports to the Senior Special Collections Conservator.

The Conservation Librarian collaborates closely with curators, collection managers, and archivists to select appropriate conservation actions for collections materials. They will develop, carry out, and supervise conservation actions on a wide range of materials, including books, archival documents, works of art on paper, photographic materials, and a wide variety of ephemera and composite objects. They will uphold the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice in their work. They will collaborate with colleagues in the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department to further our understanding of cultural heritage materials through various means, including examination, written and photographic documentation, materials testing and analysis, data collection and evaluation, and historical research.

The Conservation Librarian participates in library-wide committees, activities, and special projects, especially those involving collections storage, transport, and exhibition; construction and/or renovation of collections spaces; and emergency preparedness, response, and recovery. They will be responsible for purchasing supplies and equipment for the conservation operations. The Conservation Librarian project-manages all contracted conservation treatment work.

The Conservation Librarian will attend professional meetings, workshops, and conferences for training and continuing professional development to remain current in their knowledge and maintain active membership in conservation professional organizations.

The start date for the Conservation Librarian position is October 3, 2022.

Research

Tenure-track Faculty Librarians explore their own active research agenda, contributing their expertise, experiences, and investigations to build new knowledge in their chosen areas. The Conservation Librarian will be well-positioned to make substantive contributions to research in several areas, including, but not limited to, technical explorations of library and archival materials, conservation theory and practice in a research library, the application of value-based decision making in library and archives, and the latent bias in existing conservation theory and practice.

About NYU Libraries

The Division of Libraries values diversity among its faculty, is committed to building a culturally diverse intellectual community, and strongly encourages applications from members of underrepresented communities. We are proud of our organizational culture and are committed to building and sustaining a diverse, inclusive, and equitable organization that supports a sense of belonging for the staff and communities we serve. For more information regarding the Libraries’ commitment to IDBE, see the Libraries’ Mission & Values Statement, our Diversity and Inclusion Values Statement, and our Commitment to Anti-Racism.

Salary/Benefits: Faculty status, attractive benefits package including five weeks annual vacation. Salary commensurate with experience and background. Faculty at NYU, including in the Division of Libraries, have always enjoyed relative flexibility in their work, allowing for remote work as appropriate.

Qualifications

Required

Minimum one graduate degree (master’s level or higher) in conservation. A second graduate degree in library science is required for tenure.

Experience in the examination, documentation (both visual and written), and treatment of a broad range of library and archival materials.

Ability to collaborate effectively with colleagues in an interdisciplinary environment.

Demonstrated ability or interest in lab supervision, project management, conducting consultations, fundraising, and outreach to a wide range of community members.

Experience working in a laboratory environment and knowledge of local and federal health and safety regulations.

A high degree of manual dexterity, analytical, observational, and research skills.

Demonstrated commitment to inclusion, diversity, belonging, equity, and accessibility.

Preferred

Experience with multi-band imaging techniques

Experience with technical examination tools and techniques, including but not limited to microscopy, microchemical spot testing, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy.

Experience or interest in working collaboratively with living artists’ archives, including conducting artist interviews.

Familiarity with social media platforms and using social media for outreach.

Experience with grant writing and management.

Experience or interest in preparing library and archival materials for exhibition and loan.

Interest or experience in organizing and leading workshops.

Application Instructions

We would love to hear from you! To ensure consideration, submit your CV and letter of application, including the contact information of three professional references to http://apply.interfolio.com/103978 NYU Division of Libraries requires all candidates for this position to supply a statement demonstrating their dedication to inclusion, diversity, equity, and belonging as part of their application. Access the Diversity Statement prompt here https://nyu.box.com/v/diversity-statement Applications will be considered until the position is filled. Preference will be given to applications received by May 25, 2022

Equal Employment Opportunity Statement

For people in the EU, click here for information on your privacy rights under GDPR: www.nyu.edu/it/gdpr

NYU is an Equal Opportunity Employer and is committed to a policy of equal treatment and opportunity in every aspect of its recruitment and hiring process without regard to age, alienage, caregiver status, childbirth, citizenship status, color, creed, disability, domestic violence victim status, ethnicity, familial status, gender and/or gender identity or expression, marital status, military status, national origin, parental status, partnership status, predisposing genetic characteristics, pregnancy, race, religion, reproductive health decision making, sex, sexual orientation, unemployment status, veteran status, or any other legally protected basis. Women, racial and ethnic minorities, persons of minority sexual orientation or gender identity, individuals with disabilities, and veterans are encouraged to apply for vacant positions at all levels.

Sustainability Statement

NYU aims to be among the greenest urban campuses in the country and carbon neutral by 2040. Learn more at nyu.edu/sustainability

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recordings now available from NYU Libraries Preservation Week 2021

The following recorded events were presented as part of NYU Libraries' Preservation Week series of programming. Preservation Week is an annual initiative of the American Library Association aimed at connecting our communities through events, activities, and resources that highlight what we can do, individually and together, to preserve our personal and shared collections.

Investigating Plastics in The Special Collections

Link to recording here

In 2020, the Preservation Department was awarded a Kress Conservation Fellowship to support research into plastic objects in our Special Collections. We hired objects conservator Chantal Stein to identify the composition of plastic items in the David Wojnarowicz Collection (MSS 092) and to establish best practices for housing and monitoring various plastic types. Our goal was to find a means to preserve these fragile items while supporting access and use. Chantal will present the results of her research.

Event Speakers:

Chantal Stein

Jessica Pace

Chantal Stein is the Samuel H. Kress Conservation Fellow in plastics conservation at the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation and Conservation Department at New York University Libraries. She received her MA in Art History and MS in the Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works from NYU, and her BA in Fine Arts and Creative Writing from Columbia University.

Jessica Pace is the Preventive Conservator at New York University Libraries, where she is responsible for environmental monitoring, emergency preparedness and response, integrated pest management, as well as handling and housing of Special Collections materials. She received her MA in Art History and CAS in Conservation from the Institute of Fine Arts’ Conservation Center at New York University, and her BA in Art History and Visual Arts from Barnard College.

Artist Interviews and Artist Books

Link to recording here

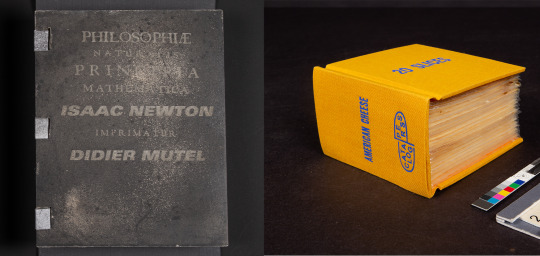

Charlotte Priddle and Jessica Pace discuss two artists' books made in non-traditional media that challenge our approach to their preservation and use. Ben Denzer's 20 Slices contains twenty slices of Kraft American Singles. Didier Mutel's edition of Isaac Newton's Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica is made of thin sheets of concrete. In both cases, conversations with the artists regarding their material selection, manufacture process, and their views on the object's aging, use, and conservation strongly informed the resulting preservation plans.

Event Speakers:

Charlotte Priddle

Jessica Pace

Charlotte Priddle is the Director of Special Collections and the Librarian for Printed Books at NYU Libraries.

Jessica Pace is the Preventive Conservator at New York University Libraries, where she is responsible for environmental monitoring, emergency preparedness and response, integrated pest management, as well as handling and housing of Special Collections materials. She received her MA in Art History and CAS in Conservation from the Institute of Fine Arts’ Conservation Center at New York University, and her BA in Art History and Visual Arts from Barnard College.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 5 :)

Hello again, and Happy Preservation Week, everyone!

This is the 5th and final installment of our Preservation Week 2021 blog series, if you missed Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 or Part 4, feel free to check them out first!

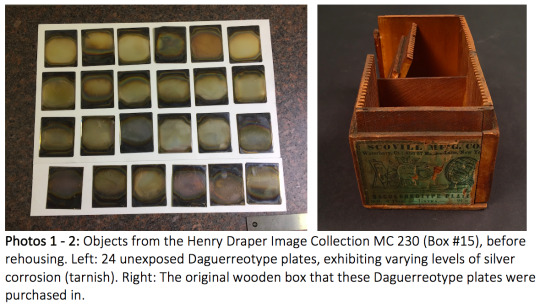

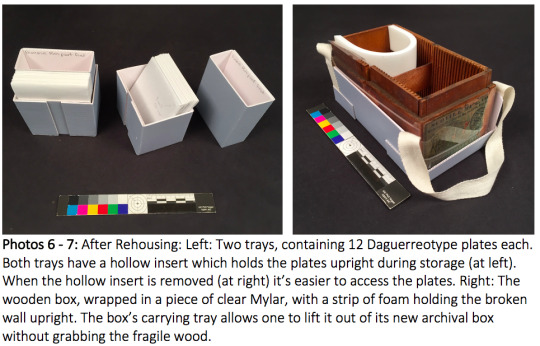

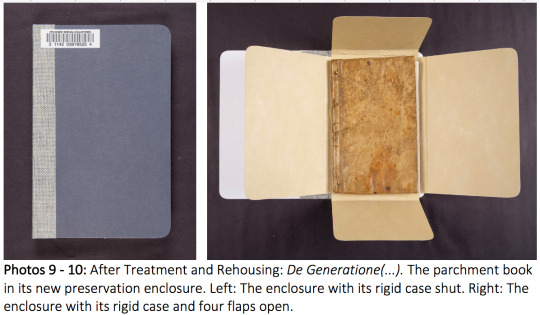

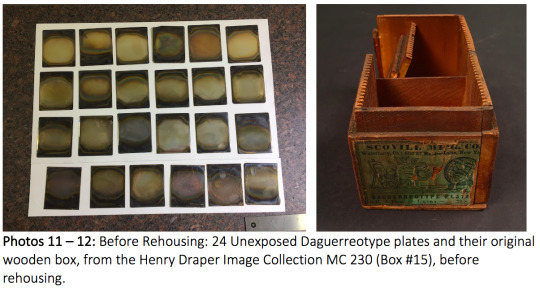

In our previous post (Part 4), I described the preservation of a set of unexposed Daguerreotype plates and the original wooden box they were issued in. For those objects, I made an (admittedly) complex preservation enclosure that will keep everything safe in storage, but it might be a little confusing to the next person who opens the box. Sometimes it’s hard to make a simple, easy to use preservation enclosure… you find yourself making a series of “simple” decisions that snowball into something complex and baffling!

In this, our final Preservation Week post, I’ll discuss a preservation enclosure that needed to fulfill a lot of different requirements, and the object that it houses is one which I never expected to find in a library! This object is part of the Outpunk Archive at NYU, which contains materials from 1989-1998 relating to Outpunk (both the zine and the queercore music label). While most of the collection consists of papers, photographs, and music recordings, there are also several T-shirts and ...a skateboard!

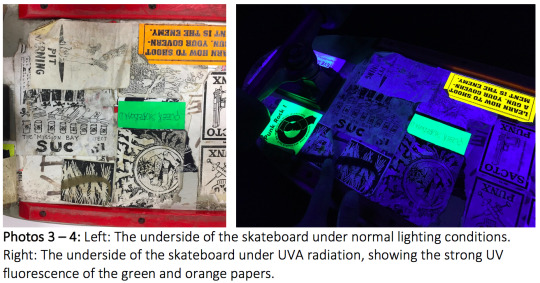

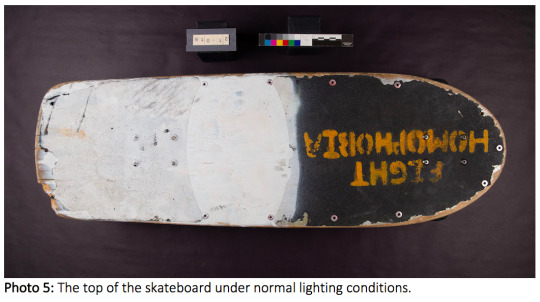

Apparently, a member of the Riot Grrrl movement owned and adorned this skateboard: one half of the top of the board is spray painted white, and the words “FIGHT HOMOPHOBIA” are spray painted in orange on the other half (Photo 1). Lots of stickers, self-adhesive labels and zine-style xeroxed drawings are pasted to the bottom surface of the board (Photo 2). This person probably lived in San Francisco in the late 1990’s, because one drawing asserts that “The Mission Bay Project SUCKS!” (Photo 3).

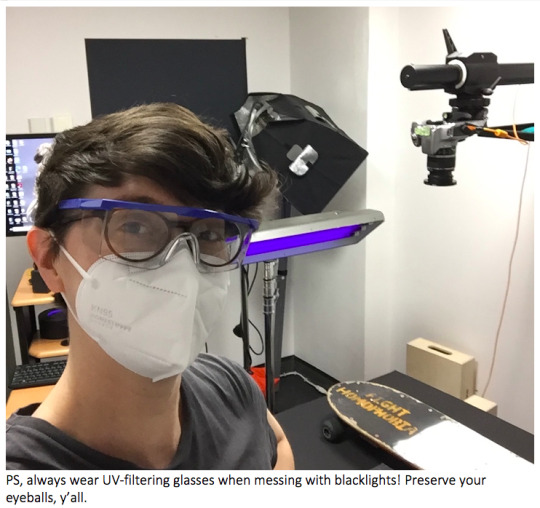

A few of the papers are bright yellow, orange or green, and these glow brightly under UV, suggesting that the papers contain daylight fluorescent pigments (Photo 4). These pigments look unusually bright in sunlight because they absorb UV radiation and reflect it back to the eye as visible light. While we were examining the top of the board under UV, we found yet another message hidden beneath the white paint... at one point, the owner of this skateboard believed that “FASHION IS A SCAM”, but she later decided to paint over this message (Photos 5-6).

So... why the heck was this skateboard in the conservation lab? Well, it’s a lot bulkier than the average library book, and since the wheels work perfectly we couldn’t just leave it on a shelf! We needed to give the skateboard a preservation enclosure to keep it from rolling around in the stacks, or being mistaken for an NYU student’s property. Most of all, we wanted to give the skateboard a preservation enclosure to prevent its minor damage from getting worse: the plywood board is cracked and splintering at one corner, the sandpapery grip tape is flaking off around the edges, and most of the stickers and drawings are torn and/or curling. We briefly discussed whether we should perform a little conservation work to stabilize these parts of the board; in the end, we decided that we didn’t want to obscure evidence of the skateboard’s use, and everything was stable enough to withstand gentle handling. ...Some may be thinking, “COME ON, it’s a skateboard! This is ridiculous.” To that I say, it’s part of an archive now! We have to treat it carefully, so it lasts a long time. :)

The library’s curators are interested in showing this skateboard during classes, and it’s possible that the object will be requested frequently in the Special Collections reading rooms. As you may recall, the main purpose of my Daguerreotype enclosure was to keep all of the components safe during storage and transit, but the skateboard’s enclosure needed to fulfill two additional requirements: it needed to be simple enough for anyone to unpack/repack easily, and because the skateboard is double-sided, the enclosure needed to function as a double-sided display mount. Under the supervision of Jessica Pace, Preventive Conservator, I created a simple preservation enclosure that would protect the skateboard and allow the curators to safely display either side.

We started by ordering a custom archival box with a drop-wall, which allows you to remove a bulky object more easily (Photo 7). Because the skateboard is a bit heavy and awkward, I also made a handling tray from cross-laminated sheets of archival corrugated cardboard. This tray (Photo 8) allows you to pull the skateboard out of the box, rather than lifting it. I also adhered strips of corrugated board to the bottom of the tray which adds a little more rigidity and allows for air-flow underneath when the tray is pulled out of the box. We decided it was best to store the skateboard wheels-down, so we had to find a way to prevent it from moving around in the box, or rolling off a table. Jessica thought it would be easiest to create bumpers on either side of the wheels, so I experimented with pieces of “Ethafoam” (low-density polyethylene foam, Photo 7). I cut four narrow strips of Ethafoam, and I wrapped them in a sheet of Tyvek fabric to prevent the foam from shedding bits of plastic inside the box. I used low-melt glue to adhere the foam to the handling tray, and I attached a pair of cotton pull-tabs to either side of the tray, to help people remove it from the box. The foam bumpers not only keep the skateboard stationary, but they can function as a display mount when someone wants to see the underside of the board. You can see the final enclosure in Photos 9-10, below:

Again, this was purely a preservation treatment, because the skateboard is in fairly good condition, despite minor damage. We chose not to repair this damage because it reflects the owner’s use of the skateboard, and the damage is not yet severe enough to threaten the object’s structural integrity. This simple preservation enclosure will prolong the life of the object and allow for conservation treatment in the future, if that becomes necessary. It may seem a little strange to treat this 20-year-old skateboard as though it were an ancient relic! I’ll admit, there were times when it felt a little absurd to apply my book and paper conservation skills to an object that (on the surface) looks like nothing special. If all goes well, however, the skateboard will survive for as long as the Daguerreotype plates or the 16th century parchment book... if so, the skateboard will teach future generations about late 20th century feminism and politics, queer history, punk rock, and alternative transportation!

Thank you so much for reading about our preservation activities at NYU Libraries this week, and thank you for supporting your local libraries!

Happy Preservation Week,

-Cat Stephens

#PreservationWeek#Preservation#Conservation#Libraries#SpecialCollections#TodayInTheLab#NYU#NYULibraries#AmericanLibraryAssociation#ALA#NYUIFA

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Preservation Week! (Part 4 :)