Text

It’s not Us, it’s You.

by Nathan Martinez

It’s been over hundred years since the birth of the first quasi-atonal work: Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, and about a hundred years since his more fleshed out serialized suite, op. 25. We’ve had a hundred years of musicians deriving their thoughts from the avant-garde ideas of atonality and serialization of every aspect of music. These ideas, along with changes in technology, have given us pieces with graph notation, pieces with tape and electronics, and even pieces with four minutes and 33 seconds of silence.

In the music world, there have been huge changes in the last hundred years, but to the outsider looking in, what’s changed? If they go to the symphony, they won’t hear works from the newest composers or even by anyone post-1950. They’ll hear works by the great romantics and classicists- which is the same thing their parents heard, which is the same thing their grandparents heard, and which is the same thing their great grandparents heard.

Now this begs the question of “why?” I know the two separate, but overlapping, categories of musicians and intellectuals will say, “American society just isn’t educated enough or understanding enough to want to hear these works of new music,” and if only “blank” were to happen then people would magically like the new music being put on before them.

However, this perspective, in addition to being snide and having the error of superiority, looks in the wrong direction. It isn’t the public’s fault that they don’t want to hear works where, only after examining the score for whatever mechanisms it was composed with, can one understand anything being heard. It isn’t the public’s fault that they feel nothing when listening to the new music that sounds like a teenager experimenting with the differing timbres of his flatulations. It isn’t the public’s fault for not wanting to hear works such as these- the fault rests with the composers.

If someone were to deny your request for a date, you wouldn’t brand him or her as being too dumb and uneducated to understand the benefits of going out with you. Yet, new music proponents (composers, musicians, critics, etc.) think that it’s perfectly fine to do so to people that don’t wish to hear their work.

Now, with a dictatorial air, these proponents will say that it’s for the public good that these things are done the way they are. “It is done because we know what’s best” is the message that comes across. All the blame is put onto the general public that just doesn’t reach their “artistic standards.” However, the poor relationship between the abusive proponents of new music and the public is one that must change.

The public has had over hundred years to process the new artistic world, and they have denied it outright. We see that just in the sheer outnumbering of old to new music performances. There’s no public thirst for farting noises, arrhythmic taps, atonal rows, or the quirks of performance art. Yet, these are exactly the things that new music offers. It offers these things because it doesn’t know what to do otherwise.

What people thirst for are ideals of greatness. From a humanist perspective, art is supposed to showcase the glory of man. From a religious perspective, it’s supposed to showcase the glory of God. But in both of these, it shows the greatness of something that is deeply ingrained into our lives. Modern music doesn’t offer this. Instead it focuses either on human mediocrity or folly, the horrors that are in this world, or simply some mathematical formula put into musical notation. Therefore, people don’t support new music willingly unless they’ve been convinced that not doing so will make them seem “uncultured.”

However, the masterpieces of ages past show the greatness that people can’t help, but want to hear. Who hasn’t been moved at the opening of Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto, brought to tears in second movement of Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto, felt the thunderous rush of singing the Ode to Joy in Beethoven’s 9th, or been in total wonder at the musical architecture of Bach’s Mass in B Minor? These pieces and the ideals in them are what people crave. It is no wonder why people don’t want to hear new music when the ideals of greatness are a lacking feature, and the mode of communication is some foreign language no one can understand. Imagine some crazy person ranting and raving at you in smashed together syllables- you probably wouldn’t know what they were saying, and if they talked for long enough, you probably wouldn’t care.

Yet, this is exactly where we are. For a century, new music has been trying to communicate to us in some harsh language that we don’t understand. The proponents have yelled at us for so long that we no longer care what they have to say. They scream, “This is music! This is what’s best! If you don’t like it, then who needs you!” Well, we don’t need new music, if there’s nothing of value in it to us. There’s not even shock value anymore. Nothing is shocking in hearing random dissonant noises, foreign instruments and idioms, or music relating to some political or social cause. In music, nobody experiences some revelation by what they hear anymore, but are more often than not, just completely annoyed by it.

What we need is a return to an artistic medium of expression that people can relate to and one that inspires. People speak with their wallets, and what they’re saying is they want a return to music that does this. That is why concert halls are filled with people when the old masters are played, yet completely barren when more contemporaneous compositions are performed. The composers of ages past knew that music has to be understood, it has to be connected to society, and it has to show the greatness of life. If new music proponents can’t understand this then they will become more and more irrelevant as time marches on, and we will be happy to ignore them.

0 notes

Text

The Audience Applauded. So What?

by Evan Pengra Sult

The relationship between musicians and their audience is central to any performance; in fact, without someone watching, it’s not a performance. But like so many long-term relationships, the one between classical musicians and their patrons has grown stale. We go through the motions, but the passion flares only occasionally. Consider the last symphony or opera you attended – I bet I know what happened. You went, sat politely through each movement, and clapped when it was over. Perhaps you stood, if everyone else did.

Does it feel discouraging to have an artistic experience summed up thusly? It was for me when I reflected on how many performances I’ve attended that have followed this model. But not all of them; one of the concerts I remember most vividly was a performance of Beethoven’s 9th during which one audience member was so thrilled by the 2nd movement that he burst into spontaneous applause upon its completion. His excitement, which he couldn’t contain until the end of the symphony, spread through the hall, bringing smiles to many (including those onstage).

I wish this sort of moment were more common; after all, there isn’t any special artistic meaning in the silences between movements. When the conductor’s baton is down, the orchestra members shuffle around, turning pages and setting mutes. That space might as well be filled with appreciative noises – indeed the act of letting them out could allow audiences to focus more closely on each movement. It’s true that there are multi-movement works meant to be heard uninterrupted, and that’s fine. It shouldn’t be hard to communicate that fact either visually (the conductor doesn’t lower the baton) or in the program notes. In fact, I’ve attended a number of recitals in which performers requested silence following certain works to better encourage reflection.

This makes sense - reflection of some kind is often the point of an artistic experience. But where in our current system is there a place to do so? The more daring programs are those which take the risk of ending a concert quietly; daring because audiences tend not to respond with the applause they provide for more bombastic finales. For performers, this can be disappointing. It’s hardly surprising given the entrenched etiquette that they should judge a performance’s success based solely on the decibel level of its reception. But the reverse is problematic, too. This was brought to my attention by the Chicago Symphony’s recent performance in Berkeley: they offered as an encore Schubert’s sublime entr’acte from “Rosamunde,” a work of understated (read: quiet) beauty. The standing ovation which followed may have been flattering, but it completely killed the mood.

This is all dancing around an even bigger issue: whether to applaud at all. I distinctly remember the first time I chose not to applaud; the performance had done nothing for me, and I decided my opinion, my silence, was as valid as the opinions of my fellow patrons. It was empowering, and I’ve never looked back. If I don’t care for a performance, I’ll offer brief polite applause to acknowledge the efforts of the performers, but that’s all. I certainly no longer stand if I’m not moved to. I’ve gone to the other extreme, too – I’m not afraid to shout “brava” for a soprano I love, even if I’m the only one, and I’ll happily lead ovations for performances I’ve found extraordinary. It feels great to be actively involved in the interaction between performer and viewer.

Art is meant to live and breathe, especially so with the performance-based forms, transitory by nature. But classical music performance has been ossified over time, frozen by dictums about the proper relationship between the performers and their audience. Is it wrong to want to inject a little spontaneity into the proceedings? Imagine, if you will, attending a performance where you clapped after every movement which roused you, and offered respectful silence after those which seemed to demand it. Imagine saving your loudest applause for the performances which really touched you, and offering only a tepid response for those which were boring or unpleasant. Imagine if your response, your choice whether to bring your hands together, actually made a difference.

0 notes

Text

At SF Symphony, a Mixed Bag

by Evan Pengra Sult

With the recent announcement that Michael Tilson Thomas will be soon be retiring from his position with the San Francisco Symphony, you might expect his remaining concerts to have a sense of urgency or excitement about them, especially when they feature music he’s been a noted champion of. You’d be wrong. The November 5 concert at Davies Hall offered an intriguing program: Bernstein’s meandering, loosely programmatic Second Symphony paired with Richard Strauss’ meandering, loosely programmatic tone poem Ein Heldenleben. Sadly, the performances were shockingly uneven, the utter lack of vitality in the Bernstein standing in stark contrast to the verve and splendor of the Strauss.

Bernstein’s Second Symphony is subtitled “The Age of Anxiety” and takes as inspiration the Auden poem by the same name. Meant to capture the postwar moment with its heady cocktail of youthful hijinks and existential ennui, it veers between spiky, dissonant syncopations and eloquent, sighing lyricism. But none of that was on display on Sunday. With Jean-Yves Thibaudet as the underwhelming piano soloist, the orchestra rarely rose above a mezzo-piano dynamic. Everything was just too delicate, too French, and depressingly bland. While Thibaudet and the Symphony did succeed in bringing some clarity to challenging music, they did so at the expense of warmth, contrast, or direction. The end result captured a very different era: The Age of Xanax.

Signs of life returned after intermission in Strauss’ popular Ein Heldenleben, usually translated as A Hero’s Life. With its soaring melodies, full-bodied orchestration, and expressive chromaticism, it’s a prime example of why Strauss is such an audience favorite. If the performance was anything to go by, it’s a favorite of the orchestra, too, for they brought to it all the bombast and ardency that was missing from the Bernstein. Constructed from a series of musical episodes, Strauss’ tone poem tells the story of an unidentified Hero (who many interpret to be Strauss himself) who finds love, goes to war, returns triumphant and eventually reaches apotheosis. Concertmaster Alexander Barantschik did an admirable job serving as soloist during the “Hero’s Companion” section, which is meant to portray Strauss’ wife. Assuming Strauss’s portrait is accurate, you have to wonder what their home life must have been like, for the music shifts, lightning-fast, between charm and fury. In a later section, “The Hero’s Works of Peace,” Strauss cleverly mingles music from his previous compositions. This includes a particularly humorous passage where the heartfelt oboe solo from Don Juan (played with aching beauty by Eugene Izotov) is interrupted by the jaunty clarinet riffs from Till Eulenspiegel.

But despite all the fun, the second half of the program couldn’t make up for the disappointment of the first. Strauss’ music, lovely though it is, can be heard regularly both at Davies and in symphony halls around the world. But “The Age of Anxiety” is a relative rarity, and it’s a real shame it didn’t receive better treatment, particularly because it’s part of MTT’s yearlong tribute to his musical mentor and his ongoing quest to champion American composers. That continues November 10-12 with the symphony playing music by Ives and Gershwin; here’s hoping Tilson Thomas and the Symphony give it some life.

0 notes

Text

New Music, SFCM, and the works of San Francisco

Nathan Martinez

11-8-2017

The San Francisco Conservatory of Music’s New Music Ensemble, led by Eric Dudley, continued the institution’s centennial celebration with a concert this past Sunday- and what a celebration it was. The concert featured works by Julia Wolfe, John Adams, and Ernst Bloch- all figures connected to the Conservatory or the city of San Francisco.

Ernst Bloch’s Four Episodes has to be the great work of the program. The first and the last movements were the most engaging, but that’s not dissing the other two. The Humoresque Macabre begins with the strings playing a jarring opening chord that then descends into the woodwinds playing a quietly limping rhythm. The movement’s character is displayed by the music being built up then dying down. This gives an ever-ominous impression that a dark beast is getting closer. You shut your eyes as it nears, but then open them to find that it has vanished- only to spot it in the distance moving towards you once more. The back and forth between the blaring attacks from the orchestra and quiet creeping rhythms, make this piece extremely effective.

The finale, Chinese Theater, San Francisco, opens with a processional of “wild warriors and terrifying dragons” depicted with percussion, piano, cello, and double bass. Again, Bloch balances two ideas: one of the dark and wild against the other of a lighter, sweeter appeal. Despite having no authentic Chinese instruments in the work, Bloch makes the Western orchestra depict the Eastern sounds perfectly. The second movement, Obsession, is a theme and variations that begins with the piano playing a theme that moves throughout the orchestra; and Pastorale gives us a beautiful melody that tucks us in with a calming musical blanket.

Julia Wolfe’s Vermeer Room, is an exploration of saturated sound. In Wolfe’s own words the piece was meant, “to capture an image, but not portray it.” This image that she’s trying to capture is in fact a painting by Jan Vermeer called The Sleeping Girl. From this painting Wolfe focuses on two things: the image of the girl sleeping, and the people that can’t be seen in the painting due to Vermeer painting over them. How does she do this? She focuses on what the girl is experiencing while sleeping there- head resting against arm, arm resting against table, two unknown hidden figures in the doorway. She creates what she calls a “rolling sea of sound” with color changing orchestration around constantly beating percussion. Her incredible knack for orchestration and musical presentation allows us to become drenched in waves of the orchestra, which even the master, Maurice Ravel, would be proud of.

The other piece, John Adams’ Common Tones in Simple Time was a poor choice for the ensemble. It was apparent that it was one of Adam’s first explorations in minimalism with 20 minutes of constant pulse and boring musical material. A later, more fleshed-out work of Adams would have been more enjoyable, but because one didn’t’ have to pay attention to the work it went by quickly.

However, this didn’t take away much from a very enjoyable concert. With Bloch and Wolfe covering the Adams, the Conservatory’s centennial celebration went off splendidly. The New Music Ensemble gave a great performance of music that welcomes listeners into the concert hall- something new music needs.

0 notes

Text

Cold Performances and New Music

Nathan Martinez

10-29-2017

Anssi Karttunen and Nicolas Hodges: Pieces for Cello and Piano

Saying that something is “dry” is a polite way of saying something is “boring.” And yes, one can fling a bunch of differing adjectives at it, but it will still come down to “the concert was a real bore.” It’s one thing when the music isn’t intriguing, but when the performers themselves are boring to watch and listen to, that brings it to another level.

Finnish cellist, Anssi Karttunen, and English pianist, Nicolas Hodges are a case in point. Their arid and cold performance on October 29th was one for the Scandinavian tundra. They played a combination of new music, including US and world premieres of works, along with some romantic favorites. However, they gave us the barebones production no matter what the era of the piece was.

Mr. Hodges was primarily in the background of the concert despite having many forward-placing passages, while Mr. Karttunen was stoic and impersonal. Neither showed emotion either with themselves or in the music. Though they churned out every work with precision, their performances were found wanting.

However, their dull renderings are perhaps perfect for the new music portions of the concert. Mr. Karttunen is best known for his new music performances, having over 160 world premieres of works, including one the other night: Fred Lerdahl’s Duo for Cello and Piano. It, along with Ashkan Behzadi’s Fling (another US premiere), were typical modern works of music. They were atonal, featured lots of obnoxious sounds, contained constantly changing and complex rhythms, and lasted for over ten minutes each. Little about them contained anything human regardless of the performers, so maybe Mr. Karttunen was the right man to play them.

Pascal Dusapin’s Slackline was by far the most interesting work of the concert. The piece constantly changed character and gave differing sound worlds with every movement. All of its titles were absurd in name, but one didn’t mind it. Peaceful was eerie and relentless. Feverish… Impatient… had a lot of jazz-like zing to it both harmonically and rhythmically. Calm reminded one of Bartok’s Concerto for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta with the cello’s haunting and beautiful harmonics. Exuberant (but not extravagant) was “extravagant” in that it was the longest of all the movements and acted almost like a whole sonata by itself. Overall, this US premiere is welcomed work of new music and completely overshadowed the other two new music pieces on the program.

The other two works on the program, Beethoven’s Fifth Cello Sonata and Brahms’ Second Cello Sonata, came off as opposing works. Though, both being from the “romantic era,” Beethoven’s sonata is light, while the Brahms’ sonata is emotionally heavy, complex, and written nearly seventy years after the former work. However, their differences in affect didn’t matter due to Mr. Kartunnen’s emotionally empty performance. It’s a real shame, especially for the Brahms, but with great music, the work’s true intentions shine through even with the most unentertaining of performers.

The Brahms is a masterpiece, with four movements guiding us through the master’s mind. Allegro vivace starts with a proud cello theme that is perfectly accompanied by the piano. Adagio affettuoso gives us the emotional heart to the piece. It begins with some cello pizzicatos and a gently waltzing piano, which quickly moves, as Brahms often does, to a gorgeous and tender motif that expands throughout the entire movement. Allegro passionato bubbles with romantic vigor, having the cello and the piano fight for leadership. However, the cello eventually wins out. Finally, the Allegro molto rounds up the work by combining all the previous descriptors together, giving us a satisfying ending to the piece.

The highlights of the concert exist in the music itself, not the performers. Brahms Cello Sonata No. 2 and Dusapin’s Slackline, one old and one new masterwork, were the takeaway from the night, and will thankfully live beyond it.

0 notes

Text

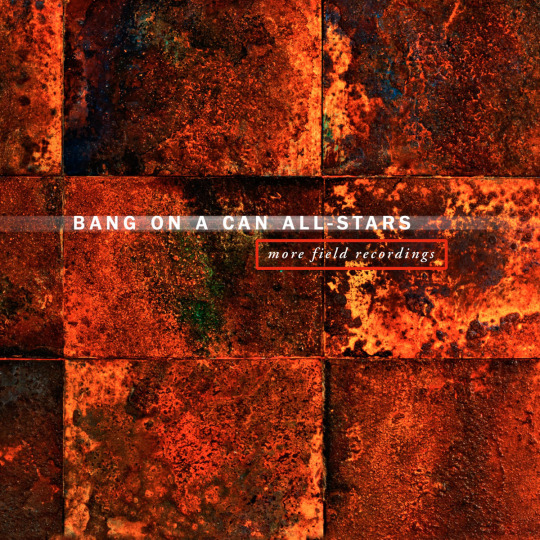

“More Field Recordings”

by Evan Pengra Sult

Prerecorded sounds permeate our lives, to the point that they fade into the background – when’s the last time you really listened to that soothing voice making safety announcements at the airport or the nature sounds being piped into your salon? But while we’ve been tuning out, the endlessly engaging contemporary music ensemble Bang On A Can has been keeping their ears wide open. For their latest CD, more field recordings, they asked 13 different composers to write short works (averaging 5 minutes each) inspired by or in dialogue with pre-recorded sounds, from oral histories to birdsong. The result is a fascinating and user-friendly journey through soundworlds both ancient and modern; you’ll never hear “background noise” in the same way again.

We all have that one relative whose stories drag on and on, seemingly without point, but what if instead of listening to the words, we heard their speech as pure patterns of pitch and rhythm? This seems to be the concept behind Caroline Shaw’s “Really Craft When You,” the opening track, and one of the most intriguing works of the bunch. As a tape plays of a group of women explaining how they make quilts, David Cossin’s subtle percussion accompaniment sneaks in and slowly expands to include cello, clarinet, guitar, and piano. Yet the overall effect is to emphasize the natural beauty of the spoken voice, its soothing rhythms and pleasant lilt.

If you’re feeling jazzy, turn up Richard Parry’s “The Brief and Neverending Blur,” well-suited to a dark and smoky nightclub with its melancholic ennui just the thing to listen to as you nurse your scotch and heartbreak. Flirt with danger and dance a tango to Jace Clayton’s syncopated “Lethe’s Children,” featuring the sultry sounds of Ashley Bathgate’s cello mixed with recordings of ocean waves and what sound like early arcade games. Or treat yourself to a night on the town with René Lussier’s “Nocturnal,” which wails with all the intensity of early bebop, then gives way to an eerie silence punctuated by low and steady breathing.

The remaining tracks fall fairly evenly into one of two stylistic categories: rhythmically driving or slow and brooding. Of the former, Glenn Kotche’s “Time Spirals” is particularly catchy, reminding me of a train station in, say, Istanbul – Middle Eastern harmonies, percussion imitating locomotive noises, and voices reminiscent of loudspeaker announcements mingling to create an indelible impression. In the more brooding vein, Shouwang Zhang’s “Courtyards in Central Beijing” is deceptively simple; gentle winds and distant birdsong overlay Vicky Chow’s pulsing keyboard accompaniment. Somewhere between a heartbeat and a factory machine, it grows ominously as the track progresses, technology slowly suffocating nature.

Bang On A Can recently celebrated its 30th birthday, but middle age shows no signs of arriving; their fresh and daring approaches to new music remain a standard to aspire to. With this 2-CD set, a follow-up to the original field recordings (2000) they’ve showcased that rare thing: contemporary classical music that is easily approachable, even by a novice, but with serious artistic goals. The pre-recorded tracks are never gimmicky, and the compositions are neither offensively complex nor dumbed-down. With any luck, it won’t take 17 years for the next installment, but however long the wait, it will be worth it.

0 notes

Text

The Organ as a Monument

by Nathan Martinez

What is it about the organ that’s so alluring? Is it that the most prolific composers in history have mastered it? Is the immensity of the instrument with thousands of pipes at the player’s beck and call? Is it the sight of the organist whose use of all four limbs resembles the most outstanding machinery? Or is it the music that comes forth from those pipes, with differing lines and colors that normally only an orchestra can create? Well, when it comes to multiple-choice tests, the answer “All of the above” is usually the correct one, and so it is here. The organ is all of these things, and because of it, it’s a testament to Western music itself.

Nathan Laube’s performance, last Sunday at Davies Hall, preached this testimony. He commanded all 8000 pipes of the organ to carry out his will. It didn’t matter if he was playing theme and variations, impressionistic suites, or calming pastorals. Everything felt powerful, yet intimate in their nature.

This was partially due to his presentations of the works. Even with program notes given, he invited us further into the music by speaking to the audience directly- giving his insights in what we were hearing. It was a welcomed change from the “us and them/performers and audience” dynamic that prevails in so many concerts.

This friendly demeanor with the audience not only seemed to aid in his presentations of the works, but also in their execution. In the first two variation pieces: Joseph Jongen’s Sonata Erioca and Felix Mendelssohn’s Variations Serieuses- transcribed by Mr. Laube himself; he explained their significance, being that they showcase the organ’s wide-ranging abilities. These pieces displayed the power of the organ with dramatic color changes that went from resembling an entire orchestra blowing out thunderous chords, to quiet flutes whistling soft melodies. His performance of Mendelssohn’s Variations Serieuses, in particular, was enchanting. He gave every note its place regardless of the thickness of the passage. And Mendelsohn’s music can get thick as he layers on variation after variation ultimately cumulating in a fugue. However, Laube gave everything a place and built Mendelsohn’s work like musical architecture.

Another work of superb quality is Maurice Duruflé’s impressionistic suite, Op. 5. Duruflé was a perfectionist when it came to his music (He wouldn’t allow most of his works to be published and destroyed as much as 90% of it). His compositional rigor and meticulous nature are shown by the work’s intricate and changing texture in the Prelude, the soft and colorful Sicilenne, and the virtuosic Toccata. It was a marvelous suite to finish up a concert.

But any organ concert wouldn’t be complete without some Bach, which Laube put at the end of the first half. The Passacaglia in C minor BWV 582, reminded us why Bach is the master of counterpoint and the person to study for our theoretical basis of music. He also played a little known work, Pastorale, by little known composer, Jean Jules Amiable Roger-Ducasse, that lulled us to sleep.

However, Nathan Laube’s performance, charming showmanship, and incredible technique shined through it all. He reminded us that the great organ is not forgotten or banished to the pews of churches and cathedrals, but has it place in the concert halls of the world, including Davies Hall in San Francisco.

0 notes

Text

A Resonant Evening of Song

by Evan Pengra Sult

Human nature hasn’t changed much over time; the same issues that governed our forebears’ lives continue to define our own. That, at least, was the takeaway from the October 20 concert of Medieval and Appalachian Songs at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Under the direction of Corey Jamason, ten singers performed a program of unaccompanied songs, offering a series of musical portraits that would not be out-of-place in our modern world. Here was the grieving war-widow, only this time her husband was lost in the Crusades, not Niger. There was the confirmed bachelor warning against the perils of marriage. And here, there, and everywhere were umpteen young lovers, from the worldly and saucy to the earnest and mournful.

Most of the Medieval music was unfamiliar –many of the songs are of uncertain origin, and those which aren’t don’t boast “household name” composers (Guiot de Dijon and Juan del Encina, for instance, don’t show up on most “greatest hits” albums). The traditional Appalachian music (all anonymous) rings a less distant stylistic bell, for much American folk music shares similar idioms. But in truth, no prior knowledge of either genre was needed; the universality of the subject matter – love, sex, family, death – made it easy to follow each musical story.

Language was no barrier, either: Karen Notovitz was equally compelling in English as a young battered wife (“The Single Girl”) and in Old French as a lovestruck damsel (“Au renouvel du tens”). She shined with her expressive timing and use of vocal shading to create different characters within the same work. Two other standout performers: Jessie Barnett, whose “Barbara Allen” plumbed the depths of heartbreak and the joys of reunion, and the formidable Elizabeth Dickerson, who offered both a moving, operatic widow’s lament and closed the first half of the program with the curious tale of “The Miller’s Will.” This narrative song tells of two sons who compete unsuccessfully to inherit their father’s business as he lies dying. Separating each verse is a nonsensical refrain (which Ms. Dickerson performed with great relish), somewhere between an onomatopoetic imitation of the noise of the mill and a precursor to “ob-la-di, ob-la-da, life goes on.”

Interspersed with the unaccompanied songs were instrumental works, there for pure enjoyment rather than any obvious programmatic intent. Among them, violinist Shelby Yamin gave a particularly arresting account of Heinrich Biber’s solo passacaglia, a set of continuous variations over a descending lament. She may not have been singing, but her voice came through clearly.

The biggest flaw in the programming was structure; there seemed no order to the way in which the songs were presented. They were not evenly separated by era or performed in regular alternation. At first I thought they might be organized thematically – the second half was shaping up to be “sad songs” until Radames Gil’s jaunty, hilarious performance of “The Shoemaker” blew that theory out of the water. Yet the more I sat there, the more I wondered if maybe this was exactly the point. Life isn’t ordered; it’s a jumble of emotions and experiences. We fall in love, we fall out of love, someone dies, someone is born. Life goes on.

0 notes

Text

CSO Dazzles in All-Brahms Concert

by Evan Pengra Sult

It's not the most scientific of methods, but you can get a fair measure of an orchestra’s greatness by the level of audience noise. Merely mediocre ensembles are met with near-constant fidgeting, while the best are so captivating that patrons hold in their coughs during the music and let them out only in the pauses between movements. At the Chicago Symphony's October 15 concert in Zellerbach Hall, an almost hypnotic stillness descended while the orchestra was playing, and for good reason! Under the baton of music director Riccardo Muti, the CSO offered probing performances of Brahms’ Second and Third Symphonies, the orchestra’s spectacular blend perfectly suited to these rich, elegant works.

Muti, a stately, leonine figure walking onto the stage, utterly transformed once on the podium. His lively, balletic gestures brought forth the most glorious of sounds, rounded and mellow in all dynamics – there was not a sharp edge to be found, even in the most active sections. It’s a shame the CSO chose to present the two symphonies in reverse order, for a chronological program would have better shown Brahms’ development – the way that the flaws of the over-massaged Second Symphony are fixed in the hauntingly beautiful Third.

The shortest of his four symphonies, No. 3 has always struck me as Brahms at his most Russian. A nostalgic grandeur saturates the work, sparking images of lavish parties at grand country estates. After a majestic orchestral introduction, the first movement unfolds as a sweeping dance, interspersed with a lighthearted pastoral theme in the clarinet (the sweet-toned Stephen Williamson). The second movement, an understated chorale, showcased the lush warmth of the CSO’s strings and the extraordinary dynamic range of the winds, their pianissimos unbelievably soft without ever sounding strained or losing projection.

The heart of the Third Symphony is its Chekovian third movement. If anyone’s looking to score “The Cherry Orchard,” look no further: the wistfulness of the slow waltz perfectly evokes times past and dreams lost. Taking a surprisingly slow tempo, Muti found the pain and longing under the smooth surface. By the end, you wondered why anyone would ever dare play it faster. The fourth movement, a lively allegro which moves from keening wails to joyful triumph, parallels Dvořák in its folk idioms. The final moments, a gentle fading away, were marred by the concertmaster's early entrance on the last note, the only blot on an otherwise flawless performance.

Symphony No. 2, heard after intermission, was given an equally polished rendition. It is a testament to the CSO's ability that they managed such a warm blend, given the shrillness of some of the writing – high woodwinds and strings often predominate without any lower voices to provide balance. Muti also brought surprising cohesion to the overlong first movement, using the many thematic repetitions to showcase the orchestra’s dynamic and emotional range – one time loud and bombastic, the next quieter and more reflective.

After a heartfelt speech acknowledging those affected by the fires and a general plea for unity from "the civilized world," Muti led the symphony musicians in a touching rendition of the third “Entr’acte” from Schubert's Rosamunde. The thunderous applause that followed broke its tender spell, and the silence.

0 notes

Text

A Clueless Centennial

Nathan Martinez

10-16-2017

San Francisco Conservatory Centennial Concert

Last Monday, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music celebrated its centennial birthday in the only way a school of music can: a concert. Now, every party needs a theme. The Conservatory chose new music. Every party needs guests. Faculty and alumni compositions and performers fit the bill. Big names are needed for such an occasion. Sergio Assad, Marc Teicholz, and Jeff Anderle graced the program. Good. All of these things were their selling points and the centennial celebration was their commemorative wrapping. It was their gift to you. However, some gifts you just want to send back.

With only new music being performed, the affair was tough to get through. This wasn’t due to the performers, but to the composers. The music itself was lacking in depth, originality, and overall entertainment value. To make matters worse, no program notes were given and explanations from the stage were only given on two works on the nine-piece program. With only two instruments throughout the night (guitar and bass clarinet), the music had to speak for itself. What it was saying wasn’t always clear.

Giacomo Fiore opened the night with Kenji Oh’s Yoshitune senbon Zakura- Josetsu Horikawa. It was ten-minute “Zen Garden” snooze; complete with gimmicky taiko drum and muted string effects on the guitar. The piece ended up being a poor opener, especially since its meditative nature didn’t change throughout all five movements. This was followed by Stefan Cwik’s “Sonata for Guitar,” which livened up the night. Larry Ferrara played the work well, even if he was dynamically static. Mr. Cwik’s last movement of his Sonata, Allegro Fuoco, had a fiery theme that concluded the work with a suave touch. Finishing up the first half was Marc Teicholz playing Sérgio Assad’s Imbricatta- set of variations of non-stop rapidly moving notes. It was the true shred-fest one looks for when going to a guitar concert.

The second half had less variety of musical ideas, as well as less differing musical timbres. It consisted of Jeff Anderle’s bass clarinet in every piece on the program with differing amounts of said instrument in each piece. All of the works fell into three genres without much variation: 1. Noise music, 2. Fast bouncing notes with a melody over it, or 3. Elegiac cries. The first category arrived with the half’s opener, Olga Neuwirth’s Spleen, which sounded mostly a like a teenager attempting to make differing fart noises in the middle of class. Fast bouncing notes with a melody on top came with Ian Dicke’s Profiteering, Ryan Brown’s minimalistic Knee Gas (On), and Max Stoffregen’s DJ-infused Black Oak. Despite the adjectives, their actual differences were little. The elegiac choral works were Kyle Hovatter’s Under the Presence and Jon Russell’s Supra. Both gave the same effect: long, drawn out, melodic layers that are extended far beyond their actual use.

If the second half had less music on it, the concert might have been more enjoyable, but it still leaves us with the problem of quality of the music. If the performers are perfect, but the compositions performed are not, who’s at fault? If the Conservatory is trying to celebrate their birthday with unentertaining party guests, who will want to stay or come to the next party? The nature of a concert is one of giving an experience. If that experience is unpleasant, how much longer will the celebrations continue? After all, you only turn a hundred once.

0 notes

Text

Urbanski: Commander and Chief

Nathan Martinez

SF Symphony: Penderecki, Mendelssohn, and Shostakovich:

Krzysztof Urbanski walks onto the stage. He’s about to conduct a rather unusual work to be heard at Davies Hall- Krzysztof Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. He signals the string orchestra to begin. We are blasted with clustered notes from the violins and violas. The cellos enter, then the double basses. Each instrument’s entrance builds anticipation for what’s to come next. Scurrying sounds give the image of people panicking and running in terror. The strings slide slowly and eerily glissando, denying us the knowledge to whether the terror is coming or has past. Time evaporates. Clusters of horror envelope the hall, immersing us in a world of sound.

It’s an abstract work to heard at symphony hall, and probably unheard of to most of the audience. It could even be an unwelcoming work. How does the SF Symphony solve this problem? With Urbanski’s theatrical conducting, that’s how. With each new point in the score, Urbanski let’s not only the orchestra know what’s happening, but the audience as well. He devilishly dances as the strings hit their bows against their instruments. He rolls and waves his fingers as they tremolo on a pitch. He signals them to slide, grow, and decay by opening and closing his arms. He brings life to the score and allows the nature of Penderecki’s work to come through to the audience.

This nature in Penderecki’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima is one of horror. Originally simply called, Threnody, it is a reflection of life for people living in terror. His own thoughts on it say that it was originally supposed to show what life was like for people in Poland as a Soviet satellite state during the Cold War. It’s not a work that gives a value judgment to the dropping of the atomic bomb. What it does show is the feeling that must have been felt by the people in the aftermath of the bomb. The work is a description of life for him, the people of Poland, and the victims of Hiroshima, because all were living in certain fashions of terror. This work reflected that fear.

Another, supposedly living in fear at the time, was Dmitri Shostakovich. A Soviet composer since his youth, his style changed as the ruler of Communist Russia changed. His tenth symphony is a four movement, almost hour-long, ride. The main message one receives from it is one of immense despair. It is a reflection of his depression under the Soviet Regime, with only short, possibly forced, movements of invigoration. These moments come in the second movement and at the last minute of the fourth. Outside of those areas, the piece is just taxing to listen to. Even with the symphony being commanded by Urbanski’s colorful conducting, the work was too long to be enjoyable.

With that being said, one must mention violinist, Augustin Hadelich, whose warm tone and stunning virtuosity made Mendelssohn’s simple concerto not a complete bore. His wonderful playing caressed each note that his violin produced. Urbanski seemed to let Hadelich lead the work as he mellowed his conducting so that Hadelich’s beautiful performance took the driver’s seat. Hopefully, Hadelich will return to play a livelier concerto at Davies soon, and Urbanski will grace us with another wonderfully led concert when he returns to the SF Symphony in two weeks.

0 notes

Text

An October Opener for the Symphony

Nathan Martinez

10-1-2017

A partnership between music and a written narrative was developed in the 19th century. Sometimes this union was vague and sometimes explicit. If the latter, it became what’s known as a tone poem. On October 1st, the San Francisco Symphony, led by Michael Tilson Thomas, showcased one of the earliest and most famous of the genre: Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantasique.

The common fable that surrounds it is that Berlioz fell into a series of decadent dreams after smoking opium. His five visions, or five movements, take us through his love affair with a girl. It transforms from him seeing her for the first time with the gorgeous Reveries and Passions movement, to her disturbing image manifesting itself in the midst of a blood orgy in Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath.

Berlioz depicts scenes of festivity that conflict with the protagonist’s despair. This first happens in A Ball where the woman appears to him in a disturbing way. He doesn’t’ say how, but it darkens his mood while he’s trying to enjoy some sort of waltz. Later in the penultimate vision, March to the Scaffold, the protagonist has murdered the woman he loves so he is being delivered to death.

However, these stories behind the music are far more interesting than what actually enters the listener’s ear. Though the work is compositionally intriguing with Berlioz’s use of the same theme throughout entirety of symphony’s 50 minutes, the work never captures the listener. It never intrigues us, and I believe that the piece would ultimately be forgotten outside of the story outlined above.

The thing that saves it is the finale, Dream of a Witches Sabbath. Here, the music is as engaging as the story is, if not more so. This movement’s most interesting aspect is the combination of a Dies Irae motif that clashes against a joyous dancing theme. The thunderous brass and thumping drums condemn the witches, but the joyous dancing thematic motif mocks this idea as the two clash against each other until the final note. The idea of light and darkness, good vs. evil, sacred against profane, made this work a controversial moment in the 19th century, but to us it’s just a good time.

Now there are times, where one has little to work with, but a good storyteller can make all the difference. Jeremy Denk’s performance of Bartok’s second piano concerto was a phenomenal story told. His complete mastery of the instrument was shown by his astounding ability to pay no attention to the extremely virtuosic passages in Bartok’s score. He engaged the audience with his showboating style that made a fun experience out of this B-grade output of Bartok’s. It was uninteresting from start to finish, with the only thing giving it any weight being the difficult piano part.

We, in the music world, have stories and storytellers- both can make our experiences worthwhile. The symphony was blessed with both during their October opener. However, it would be wise to not only rely on the stories behind the music or the inclinations of the performer. Instead, it would be better to rely on the greatness of the music itself. Hopefully, the San Francisco Symphony will program these calculations into their engagements in the future.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Florian Conquers in ‘Traviata’

by Evan Pengra Sult

There are not enough superlatives in all the world to describe Aurelia Florian’s performance on Sunday, October 1, at the War Memorial Opera House. The Romanian soprano, making her San Francisco debut in Giuseppe Verdi’s La Traviata, displayed such overwhelming artistic brilliance that it’s difficult to know where to begin. Perhaps with her effortless, effervescent coloratura? Or the way she caressed the softest of high notes with such heart-rending beauty? There was something of Maria Callas in the way she coaxed the emotional truth out of each phrase, making this familiar music sound fresh and appealing.

And familiar it is, for La Traviata is today the most-commonly performed opera in the world. The story is simple: boy loves girl, girl loves boy, boy’s father intervenes, girl dies in boy’s arms. The specific machinations get a little improbable but the music transcends it all: the ebullience of the party scenes, the poignancy of the love duets, the haunting final moments. On Sunday, the San Francisco Opera Orchestra, under the baton of Nicola Luisotti, offered a supple if somewhat sedate rendition of the score. With lesser singers, the slow tempi might have emphasized their weaknesses but with the stars in this production they instead offered an opportunity to showcase their remarkable vocal prowess.

In addition to the estimable Ms. Florian in the title role of Violetta, audiences also heard the San Francisco debuts of two rising talents: Atalla Ayan as the love interest, Alfredo, and Artur Ruciński as his unpleasant father, Giorgio. Mr. Ruciński possesses a sinister, penetrating baritone that perfectly conveyed the venal piety of his character, while Mr. Ayan’s creamy tenor was particularly effective at conveying Alfredo’s naïveté. In simple, powerful renditions of “Un di, felice” and “De' miei bollenti spiriti,” he soared over the orchestra with ease and in the various love duets, he blended beautifully with Ms. Florian, their remarkable chemistry adding sizzle and spark to the proceedings.

The tragic arc of the opera’s storyline was cleverly mirrored by the visual aspects of John Copley’s opulent production: Gary Marder’s lighting became progressively wintrier with each act, illuminating less and less of the fabulous Belle Époque sets by John Conklin. The costumes, too, told a story: David Walker’s gowns for Violetta moved from white and pale blue in the first scenes (ironically virginal, perhaps, but also indicative of the lighter tone of the story) to black and finally to a grey, shroud-like nightgown as the tale took its turn for the worse.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen a more convincing opera death than that of Ms. Florian – her gaunt features (helped by Jeanna Parham’s brilliant makeup) convulsed in pain with each wracking cough until her final collapse. To the end, though, her voice reigned supreme – no doubt the angels were overjoyed to lift this “fallen woman” into the ranks of their choir.

0 notes

Text

A Swinging Shindig: 100 Years of Bernstein

Nathan Martinez

September 24th, 2017

A march erupts: the percussionist stomps the bass drum while trombones and trumpets shriek out a fierce motif. A quintet of saxophones compete in a battle royale for supremacy. The clarinet solos over the entire ensemble- blaring out its riffs- moving its way over the band’s thunderous chorus. Is this a swinging jazz club? Are we watching the Rat Pack? No. We’re at the San Francisco Symphony, sitting in Davies Hall, and this ensemble is playing a work by the musical master, Leonard Bernstein: his Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs (PFR). It’s a brass laced, jazzy work that was composed before Bernstein struck big with his musical masterpiece, West Side Story. It was also the opener to the SF Symphony’s centennial celebration of Bernstein with the orchestra being led by Michael Tilson Thomas.

PFR featured Carey Bell on the clarinet, whose personality and showmanship shined with the ensemble. The piece’s big band nature was easily transferred to Bell as he laid down riffs that the rest of the ensemble followed as if it was a jazz standard. The only flaw to the whole thing was the ending where the enthusiastic ensemble completely overpowered Bell, who couldn’t be heard until the penultimate note. However, this was a minor flaw, and the piece had such an impact that an encore of Riffs was played right then and there. It was music that could turn any space into a swinging shindig, but PFR wasn’t the only gig in town.

Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances were also a crowd pleaser and why not? The suite from Bernstein’s famous musical is rhythmically engaging with Latin American dances intertwined into the texture of the Prologue, Mambo, Cha Cha, and Rumble. This was accompanied by the touching Somewhere and Finale movements. His American version of Romeo and Juliet, set in the streets of New York, glides to us like Fred Astaire dancing his way through America. Through the ferocious rhythms of the famous Mambo, and the touching theme of Somewhere, Bernstein reminds us just why he was the top cat in American music in his 1950’s heyday.

But sometimes all that ritz and glam needs to look inward, hence comes Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms- a piece for full choir, boy soprano, and orchestra. It’s a spiritual departure for this program with texts from the Hebrew book of Psalms. However, the quiet and lighthearted aesthetic of the first two movements didn’t make one feel the weight of the spiritual matters at hand. It wasn’t until a string interlude introduced the third movement, that one felt the weight of the spiritual humility that Bernstein sought to invoke. The self-reflecting text of the third movement (Psalms: 131) resolves the work with consolation of spirits, recognition of the Lord’s presence, and beautiful “Amen” from the choir.

Arias and Barcarolles was inspired by the President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s remarks to Bernstein after a concert where he said, “I liked that last piece you played. It’s got a theme. I like music with a theme, not all them arias and barcarolles.” However, Bernstein could have taken the advice from the former president and added some tunes that “got a theme” because this piece came off as pretentious and unfunny. This was mainly due to the atonal expressionism of the music and the wandering words of the text. Another problem arose from the mismatched pair of soloists: Ryan McKinny and Isabel Leonard. McKinny’s clear and articulate tone was a good fit for the work, but wasn’t matched by Ms. Leonard, whose unclear voice muddled the text. This made the duets even sloppier than the music allowed and the only thing that came together was last movement where they both hummed. It’s a more abstract piece on the program, but even abstract art has a certain level of achievement that this piece didn’t quite reach.

Overall, due to the opening and closing pieces (PFR and Symphonic Dances), a jazz-like atmosphere enveloped the concert hall. One didn’t necessary feel the weighty presence of classical music. What one did feel was the excitement and passion that music should bring, which is exactly what Bernstein wanted. As a media personality, Bernstein invited young people into the concert hall, and perhaps with this exclusively Bernstein program, the symphony follows through with Bernstein’s legacy.

0 notes

Text

For Bernstein, A Mixed Tribute

by Evan Pengra Sult

It’s easy to know why we honor a man like Leonard Bernstein, one of the greatest musical luminaries of the 20th century, a brilliant conductor and composer who was also a passionate educator. And with his centennial approaching next year, the when seems easy, too. The challenge is how? For Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony, the answer is to present an entire season showcasing the many sides of Bernstein’s music, from the puckishly playful to the spiritually profound. But with the first concert last Sunday, things got off to an underwhelming start. The first half of the program was marred by uneven interpretations while the second was dominated by a collection of lackluster art songs. Only the finale, the much-loved dance suite from West Side Story, brought Bernstein’s compositional gifts to vibrant realization.

The song cycle Arias and Barcarolles, which opened the second half, was a particularly odd choice for a tribute, for while its music was often inventive, what it really showcased was Bernstein’s ineptness as a lyricist. “Love Duet” tries for wry self-awareness but misses the mark completely, coming across as glibly self-centered. “The Love of My Life” displays an over-fondness for ellipsis, and the end result is not so much a series of provocative unfinished thoughts as it is vague and directionless. To their credit, soloists Isabel Leonard and Ryan McKinny did their best with the text, eliciting laughs from the audience on lines like “Why not skip this election?” Throughout, I was haunted by thoughts of Stephen Sondheim, Bernstein’s sometime collaborator, whose “We’re Gonna Be Alright” and “The Road You Didn’t Take” explore the same themes as the numbers mentioned above, but with greater subtlety and wit.

In contrast, the first half of the concert offered higher-quality writing, unevenly delivered. The usually magnificent Chichester Psalms was oddly antiseptic in the opening though it warmed up over time, with the well-blended Symphony Chorus bringing especial gravitas to the third movement. The second movement featured boy soprano Nicholas Hu, often accompanied by an effortlessly lyrical Douglas Rioth on the harp. The concert opened with the boisterous, foot-tapping Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs, a swing-influenced clarinet feature that would have been more effective had the brass section not overpowered the soloist, Carey Bell.

It is sometimes reported (perhaps apocryphally) that Leonard Bernstein regretted writing West Side Story, for it came to overshadow his “serious” compositional output. This was certainly the case on Sunday - its memorable but never simple melodies and distinct groove made for an audience favorite, and the Symphony musicians played it to the hilt. They snapped jauntily through the “Prelude,” tastefully milked the bittersweetness of “Somewhere,” and blasted through the syncopations of the “Cool Fugue” with sizzling energy. Though I wish it had been the conclusion to a more musically satisfying concert, it served at least to clear the air and remind us why Bernstein is worthy of tribute.

0 notes

Text

A New Elektra

by Nathan Martinez

SF Opera: Elektra

In any area, there is a divide between great and good, between the top 3% and the rest. In opera, this divide is evident even among the “good” singers of the day; but Christine Goerke is a part of this upper echelon of vocalists that are able to separate themselves from the herd. The proof of this was in full display in the SF Opera’s production of Richard Strauss’ Elektra. Her portrayal as the title character was entrancing. Her skill not only to execute, but to excel in Strauss’ difficult soprano part was a feat that will serve as an example to singers for years to come. Where other sopranos barely cut through the immense orchestra, she overpowers it. Where others seem to find difficultly in singing for nearly two hours straight in an opera without an intermission, she thrives throughout the opera’s entirety. Where others have difficultly in displaying the various moods of the character, she easily transports between the madness and the affection that is Elektra.

The opening scene in the opera begins with her reliving the memory of her father. The stage is set up so that her father’s role in her life becomes ever more dark: from a faint picture of him as a soldier to him lying dead in a blood-filled bathtub. Elektra succumbs to this vision of her father and views it as a mandate of vengeance, which spirals her into insanity. The music exhibits an ever-changing texture filled with large brass sections, scattered woodwind solos, and contrasting moods of rapid key-changes to show Elektra’s unhinged nature. This is countered by moments of harmonic stability that showcase Elektra’s longing for her father. These sweet minutes encourage us to view Elektra’s humanity as we connect with her wanting to bring back her father from the dead; but as both we and Elektra realize, this cannot be, which only infuriates her more, and entices us to listen further.

The tragedy continues with the introduction of a variety of characters: first her sister, Crysothemis, played by the talented soprano, Adrianne Pieczonka, who’s bright and clear tone portrays the character’s traditionalism. Her character contrasts Elektra’s madness in that all that she longs for is life of domesticity. This introduction is followed by Michaela Martens’ Clytemnestra whose sound was malicious in nature, but well executed in tone, which made her good fit for the role. This villainess has trapped both Elektra and Crysothemis and plots to have them executed along with their brother, Orest, which brings us to other star along with Goerke, Alfred Walker’s Orest. The deep baritone voice of Walker perfectly aligns with Goerke’s tone and both bring us into the world that the children of Clytemnestra lived in. Orest and Elektra’s shared vision of how to break the chains their murderous mother ends in the beheading of Clytemnestra by Orest, followed by the dance of death by Elektra.

However, the opera is supposed to be portrayed as Greek tragedy containing Greek wisdom and ethics, but this production strips it of that. Instead the opera becomes a modern tale of determinism, where no one is actually at fault for anything they do, and all are simply a victim of circumstance. None are below compassion (“below” is used deliberately). Yes, the production fills the play with more disgusting subtext (possible infidelity, incest, rape, etc.), but the overall message of the opera no longer is “Actions have dreadful consequences.” Instead the message becomes “Everyone is just a victim in a world gone mad.” The opera ideals are normally clear- a murderous and adulterous wife, a loving daughter who is drove to madness over her father’s murder, and the furies that come to destroy all from within. However in this production nothing is clear. It’s set up in a museum (or house, or in Elektra’s head, or all of the above), and not a smidge of Greek morality is present. If you wanted a remake of Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island on the opera stage then here it is; but if you came to see Sophocles’ tale of Elektra, then you’ll probably be disappointed.

Leave Keith Warner’s direction on the production of this glorious tale behind and you are left with the greatness of Strauss’ vision, the thunderous orchestra led by Henrik Nánási, the bell of the ball, Christine Goerke, and many of the most talented singers there are today. Listen to the music, and this opera separates itself from the herd; include the production and this opera just comes off as high-minded, not to the audience, but only to itself.

0 notes

Text

A Stunning, Contemporary “Elektra”

by Evan Pengra Sult

A woman locks herself in a museum and from her disturbed psyche, conjures up vengeful wraiths whose murderous, incestuous intent drives her to the brink of madness. The plot of a tawdry summer B-movie? No — rather, the concept behind the visceral, revelatory Elektra now playing at San Francisco Opera, a production which shows definitively how contemporary reimaginings can both enliven and deepen our understanding of classic works.

Central to the success of any opera are its stars, and SF Opera has assembled a high-wattage cast more than adequately equipped to handle Strauss’ brilliant, protean score. Christine Goerke, in the title role, is alternately cunning, mournful, innocent, vengeful, anguished. She brings a new coloration to each phrase, crafting a multi-layered Elektra in whom we see sides of ourselves. If only we could sing so well, too! Goerke’s voice is as versatile as her acting, from the chocolatey low register to the crystalline heights of her instrument, and her effortless control draws the audience in far better than the SimulCast screens in the upper reaches of the balcony.

Though it is her show, Goerke is not the lone star; she is part of a larger constellation. Adrianne Pieczonka brings a poignant naïveté and bell-like vocal clarity to the role of Chrysothemis, so often played as the pitiable lone figure of sanity but here given a far more convincing backstory as a developmentally stunted victim of sexual abuse. There is equal nuance to Michaela Martens’ Klytemnestra, no stereotypical dragon mother but instead a searing portrait of whiskey-drenched pathos, as much a victim of circumstance as her daughters.

Circumstance comes in the form of the men in her life: Robert Brubaker’s slimy Aegisth and Alfred Walker’s bullying, brooding Orest, both sung with sinister brilliance. In this family, the menfolk dominate, the women self-destruct in their struggle to cope, and history repeats itself — Sophocles by way of Tennessee Williams. It’s no longer a revenge story, it’s a piercing family drama. And really, it’s two: the ancient Greek tragedy of the House of Atreus and a midcentury military family’s uncomfortably parallel storyline, whose central player conjures these images from the relics of an antiquities museum.

At the risk of spoiling everything, the final moments of this one-act tour de force contain one of the most brilliant directorial decisions I’ve ever seen: Agamemnon, seated in his bath, is revealed to be not the victim of his murderous wife, but a suicide. Suddenly everything makes sense. Of course Elektra blames her mother for taking up with the abusive Aegisth, for she cannot bring herself to blame the man she never got to love. And it’s not hard to see why Klytemnestra would have been desperate for a strong masculine presence around the house, nor why she might have banished her son, at the very least a painful reminder of the life she used to have (or perhaps even the living proof of a previous infidelity?). The most outlandish aspects of the plot suddenly become the most accessible; almost no one is above compassion.

In a traditional staging, Elektra dances herself to death at her father’s gravesite; here she collapses into the arms of her concerned siblings. Perhaps now, having exorcised her demons, she might begin the process of recovery.

0 notes