Text

On Creating a Frictionless Traveller, Part II: Character Sheets

The character sheet that comes stock with the edition of Traveller I own (Mongoose Traveller1st edition, 2008) leaves a lot to be desired, although that almost doesn't matter: I don't own a scanner and can't find it online, so I needed to make my own anyway.

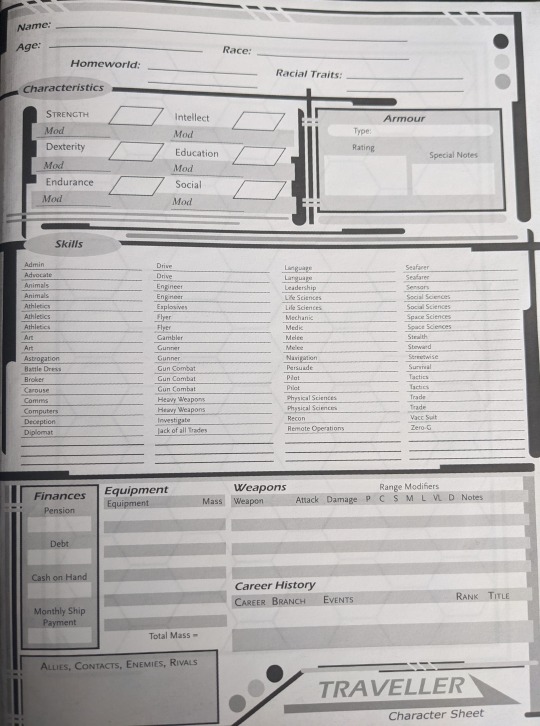

With no scan available, here's a grainy photo so you know what I'm talking about:

Here's a few issues with the built-in sheet:

1. Traveller doesn't use hit points. Instead (like Numenera, and other RPGs), damage reduces ability scores directly. The built-in character sheet doesn't have a good way to differentiate current ability scores vs. maximum ability scores.

2. Similar to D&D, ability scores grant a die modifier to skill checks. When ability scores change, so does the modifier. Unlike D&D, ability scores in Traveller can change every round. The algorithm for calculating the modifier isn't immediately obvious, so this has to be looked up every time someone takes damage.

3. Weapons and armour tend to change more often in Traveller campaigns than in D&D campaigns because many weapons are illegal on many worlds (see Post I). However, each weapon (particularly ranged ones) come with quite a lot of information associated with them, as in addition to any special rules they might have (and many do), they have damage, heft/recoil, ammo, rate of fire, and range modifiers at various distances. Armour isn't as complex, but is still annoying to change frequently.

4. As a sci-fi game, a lot of gameplay comes from neat gadgets PCs can purchase. However, space for equipment on the main character sheet is tiny.

5. Character creation involves going through several four-year terms. This generates a ton of information, but the default character sheet relegates this to a tiny corner.

My homebrew character sheet uses the following solutions to these problems (don't print these screenshots, PDFs will be available below):

1. Each ability score now has much more space, and separate boxes for the modifier, the current number, and the maximum number.

2. To solve problem #2, the table that converts ability scores to modifiers is printed directly on the sheet.

3. Instead of making players copy down the many, many numbers associated with each weapon, I made playing-card sized cards for each weapon in the book and have space on the character sheet to paper clip them in. When weapons change, it's as easy as swapping a card. Armour gets an extra mini-card for ablative or reflective overlays.

4. There's much more room for equipment on my character sheet, made up for by shrinking the Skills section. Traveller characters tend to only have a few skills, so they can write in the ones they have, rather than listing all available ones.

5. The entire back page is for character creation information.

A few things that came up since creating these character sheets that I ought to fix for a later one:

· The blank section for "Weapons" should probably have "unarmed combat" stats on it.

· There's no space for recording Rads a character has absorbed

I'm not an artist by any means. There's no question that my character sheet could be prettier. But (for my purposes anyway), it's much more functional than the one that comes with the book.

I'll include download PDFs of the weapon and armour cards, and the new character sheet, below. Margins were determined based precisely on what my printer could print, so YMMV.

Traveller Character Sheet

Traveller Armour Cards

Traveller Weapon Cards

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Creating a Frictionless Traveller, Addendum: the Law and Melee Combat

When making the table in Part I, I realized that every planet has a semi-hidden characteristic that balances melee combat. This was pretty astonishing to me, as it's buried pretty deep, but it's also a huge improvement to the game if implemented in your campaign.

The issue is as follows: Traveller ranged and melee combat is realistically balanced (which is to say, swords simply don't compare to laser guns). Traveller also lacks “sci-fi remedies” such as lightning swords and laser whips and whatnot: with the exception of the stunstick, melee weapons are pretty conventional renaissance or medieval era swords and so on. None of this is exactly a problem, but it's a little weird that, during character creation, there's quite a lot of emphasis on getting fancy swords and the Melee skill, especially Melee (Blade). A lot of career options dangle Melee (Blade) in front of players in a way that means it seems like it ought to be useful, but, on its face, isn't.

There's a little note in the rules that cutlasses and so on are popular boarding weapons because it reduces the chances that a stray shot will damage a ship's component, but there's not really any clear rule or system for how that would play out beyond occasional GM fiat. In practice, I'm pretty sure that if the party tried to rush a pirate ship through the airlock with cutlasses, and the pirates were willing to scuff their own ship and thus had shotguns, the results would be fairly predictable.

(At some point I might create a houserule to handle that (missed ranged attacks roll on a table of spaceship damage or something)).

It's fine to say "in this science fiction setting, combat is done with guns. Bringing a sword to a gunfight is anachronistic and suicidal." Most science fiction, Star Wars aside, takes this approach. But if that's the approach Traveller was going for, then… why are there all these rules for melee combat? Traveller, unlike, say, D20: Modern, isn't a spinoff of a fantasy game with a bunch of vestigial fantasy-genre-stuff. These rules were put in for a reason.

A related issue (again, not exactly a problem) is that laser weapons are vastly more effective than conventional firearms (unless the enemy has Reflec, though text in the book (and equipment of default NPCs) indicates that this is supposed to be a fairly rare item). Laser weapons are also more expensive, but the price of both are trivial compared to the amount of money Players will be dealing with in the trade system. So… why are there all these rules for conventional firearms?

The answer: because guns are illegal, laser guns, doubly so. On a shockingly large number of planets, anyway. Shocking to someone from a D&D background, anyway, where the expectation is that if a weapon is written on a character sheet, it's pretty much always available.

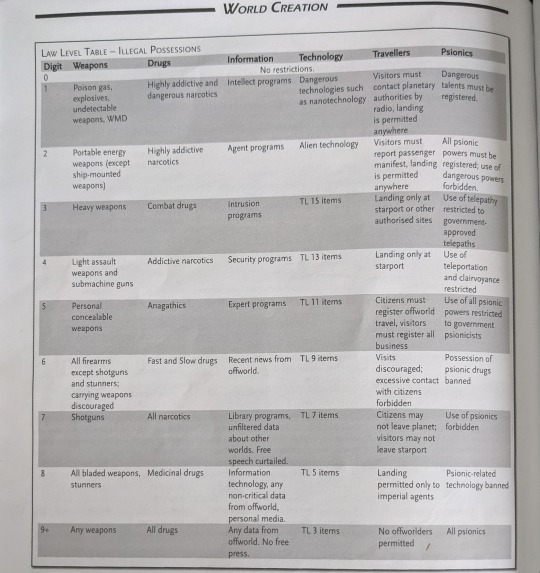

Law Level Table, Mongoose Traveller (2008) p.176

Each planet has a Government code, and a separate Law Level Table tells you which items are banned by which type of government. Most governments restrict weapons. The two most important for our purposes are "Weapons" and "Techology" (because a lot of powerful weapons are only available at advanced TL’s, also). I went through each weapon in the book and penned in the "Law Level" it becomes illegal at (this should have been in the book to begin with). The result is that nearly every planetary government restricts laser weaponry (Law level 2+ by Weapon, 3-7 by Technology, depending on the weapon in question). Some, but not all, restrict conventional firearms (Law Level 4-7+, depending on the weapon, and by around 5+, by Technology), but virtually none restrict melee weaponry, whether by restricting Weaponry or Technology. I had to make a pretty arbitrary few judgement calls (I decided any weapon with autofire, plus the extra-deadly gauss weapons, counted as "assault weapons," for example). Now, when the party goes to a planet's surface, I tell them the restrictions that planet places on weapons and technology (”Weapons Law 2+, TL13+,” for example), which they compare to the number printed on their weapon cards (see the upcoming Post II), and then they tell me if they're complying with the law or smuggling their weapons in. I have these numbers written in my notes on each planet in my GM binder.

The result of this is that there are huge stretches of the galaxy where sword-and-board fighting is prevalent (ruthlessly enforced by police who are equipped with controlled weapons), while boarding actions, which are an anything goes "wild west," are dominated by ultra-lethal laser weaponry. I know that this is the opposite dynamic to that noted by the text on boarding actions and cutlasses, which is a discrepancy I haven't yet been able to resolve. Nonetheless, it does leave a niche for both styles of fighting.

If you, as GM, are consistent with weapon and technology control laws (which means the headache of dealing with the Law and Government tables at the back of the book), it opens up many new opportunities for PC's with unconventional skills to shine. This is especially important given Traveller's quirky character creation—players don't always have a lot of control over their character's skills, so anything that puts disparate skills on a more level playing field is worthwhile.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Creating a Frictionless Traveller, Part I: Trade

I just ran Session Zero (character creation and so on) of Mongoose Traveller 1st edition (2008) with my quarantine pod. This is my second Traveller campaign that I've run (thoughts inspired by the first you can read about here), and the fourth that I've been a part of. Having learned a little from my last campaign, I've made a few improvements to the game's interface (not really houserules) that speed up gameplay and reduce friction.

What do I mean by interface? Imagine if Traveller was a computer program. The interface would be the information displayed on the screen, while the actual rules of the game are what goes on in the background. Traveller's rules, so far, are rock-solid. The basic core dice mechanics are fast and easy, and the game's many elegant systems for procedural generation allow nearly endless gameplay with only sparing need for GM-added "spice."

What isn't elegant is the way some of these systems are presented to the GM and the players. Thus far, I have isolated several systems (many of which are quite entangled with each other) that could benefit from a more polished interface to reduce friction during play (i.e., avoidable times when the game grinds to a halt and something has to be looked up, calculated, found, remembered, etc.). They are:

Trade (namely: calculating purchase modifiers, number of passengers, amount of available freight, legality of various goods)

Character Statistics (namely: character sheets, weapon and armour statistics)

Spaceship combat (namely: tracking spaceship position, responsibilities of individual crewmembers, tracking computer programs)

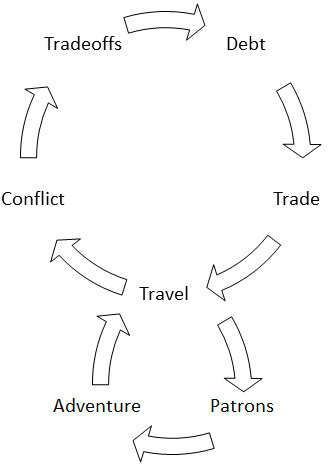

I'll start with trade because it is, I think, one of the most overwhelming systems in the game on its face, but also one of the most crucial to keeping the Traveller "loop" going. It's also part of what makes Traveller so unique.

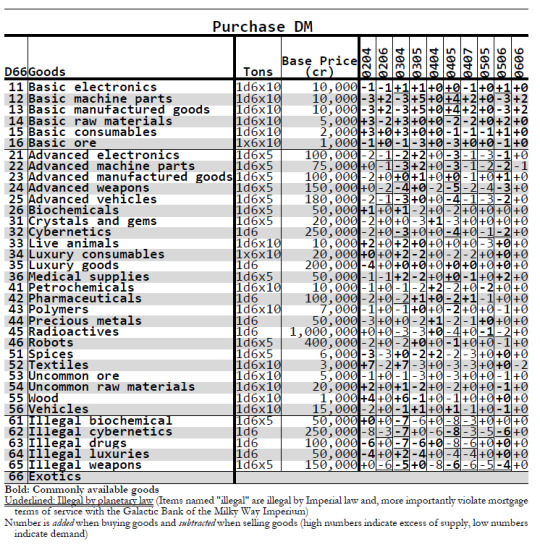

To buy cargo, a character must make a Broker skill check (easy), adding a modifier based on the value of that trade good on the current planet (easy), and compare it to a little table that converts that into the price, as a percentage, of the good's value (easy, with a calculator or smartphone). For example: to buy Basic Machine Parts, a player must roll 3D6 + 2 (the PC's Broker skill modifier) + 4 (a bonus because the goods are cheap on the current planet). The roll is 17, which a table on page 164 tells you means Basic Machine Parts can be bought at 65% of their value (normally cr. 1000/ton), or cr.650 per ton. Great. Easy enough, right?

Wrong.

The reason this can be incredibly slow is because the price modifier based on the planet's characteristics—the number that encourages the players to explore the galaxy—is a real headache to calculate on the fly. It is calculated from the following sources:

First, look up the Trade Good on the table on page 165.

Look at the Trade Codes of the planet in question (on a handout the GM generates and gives to the players at the start of the campaign)

Determine if the Trade Good is illegal on this planet. This is found by:

Comparing the planet's Government Code (on the handout) to the Government Table (on page 175) to see if a category of goods is restricted

If it is, debating for awhile whether "Advanced Weapons" are considered "Heavy Weapons" or "Portable Energy Weapons" (i.e., make a judgement call)

Comparing the Law Digit for the item from the Law Table on page 176 to the Law Level of the planet to see how illegal it is

Find the highest number in the Purchase DM category related to these Trade Codes, unless it is lower than the number calculated in step 3, in which case, use the number in step 3 (and the PCs are now smuggling! This is cool because now you can have police chases and so on.)

Find the highest number in the Sale DM category related to these Trade Codes and subtract this

Sum all of these numbers. Repeat for each trade good purchased.

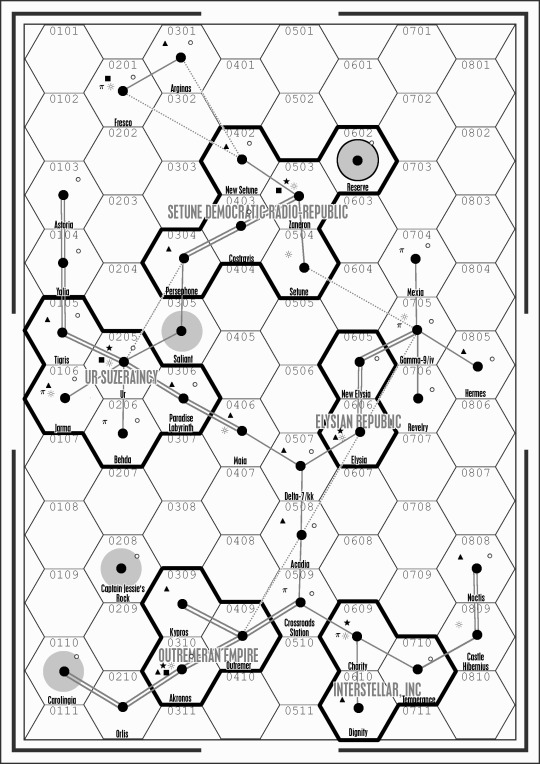

Looking at all of those steps probably convinced at least some of you to swear off Traveller altogether. But here's the thing: this is incredibly slow to calculate during play, but after the galaxy is generated, these numbers never really change. Barring exceptional events in the campaign, an Industrial world will continue to be Industrial from start to finish. My toddler was unusually chill last week, so I spent a few hours making an Excel spreadsheet that crunches this once, and only once, and spits out this table for my star cluster:

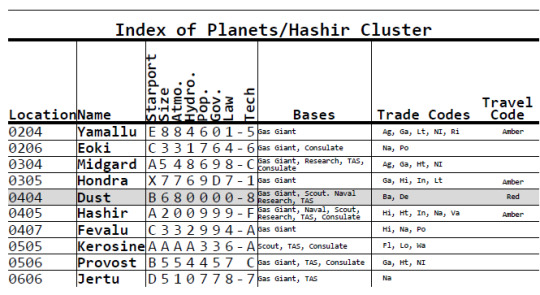

Each four-digit code along the top corresponds to a labelled hex coordinate on the star cluster map they have (i.e., a settled planet).

This table presents each planet's numerical stats. There's a lot more that goes into each planet (it's weird cultural quirks, important NPCs there, maps, etc.—you know, worldbuilding stuff) but this table is what the players need for the game's rules. Different types of survival equipment available are rated for different atmosphere numbers, for instance, and different bases provide different services. I know "Gas Giants" aren't really bases, but I didn't have space for another column for them.

I'll admit this was a slog to put together. I like spreadsheets more than most, but even my eyes glazed over a few times doing this. I also had to make a few judgement calls on what items were restricted at various law and government levels. It's also possible it contains significant errors; my spreadsheet grew more complicated than I was able to understand (and thus debug) by the time it was done. Still, it works for now, and I'm not willing to change it. It wasn't more work than, say, drawing a dungeon map, and it'll last the whole campaign. I made similar tables for determining passenger and freight availability. If I ever go back and tidy up that spreadsheet so that it’s useable for others, I’ll post it.

Now that that math is done, it stays done. I gave the players this, printed on cardstock, at the start of the campaign, and they never need to know how much work I saved them.

Buying and selling stuff now isn't any more work than any other skill check: it's a dice roll, plus a modifier on the character sheet, plus a circumstance modifier. It's quick, it's easy, it's frictionless.

Next up: a tangent in which I discuss how making this trade spreadsheet unexpectedly balanced melee combat in my campaign.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Full Plate Threshold and the Nature of Money

"Can I buy a magic sword?"

This is a question that seems straightforward, but is actually fraught with follow-on implications that are not obvious. It is also one that's asked at some point in any D&D campaign. You might be thinking, as GM, that you're making a choice about the setting of your campaign (is this a high-magic or low-magic world, a desert island, a major trade city, etc). While you are making this decision, you're also deciding (perhaps without knowing) what money is in this game. You're deciding whether your adventuring party will build castles or not, whether they'll hire armies or not, whether they'll go adventuring or not, whether they'll be greedy or not, and whether they'll care about rewards at all after the fighter gets her hands on a set of Full Plate.

In my experience, money in RPGs is used for one of six things: character power, narrative power, oxygen, skill, XP, or nothing.

Money as Character Power

This paradigm is the one most familiar to 3.x veterans such as myself, and is the direct result of allowing magic items to be purchased freely for money. This allows players to invest money in their character's powers and strengths in the same way they do with skills and feats. There is a slightly different set of constraints on how money is spent than skill points (which is to say, the party must find a city), and may be further restrictions still (such as 3.x's limitations on the most expensive items that can be bought in each size of settlement), but at the end of the day, players can pretty much buy whatever they have money for.

In essence, if a player can convert currency into better stats, damage, armour, etc., then in your system, money is character power and should be treated as such. The GM should keep a close eye on how they hand out treasure and quest rewards, as too little or too much money can easily result in difficulty balancing encounters. Third edition D&D came with a table stipulating how much money each character should have at each level (the (in)famous "Wealth by Level" table) and balanced monster CR based off of this assumption. In my younger years, I GM'd several campaigns in which I restricted purchase of magic items because of campaign setting reasons (it was a low magic setting, or the party was far from civilization, or whatever), and then was shocked as the party struggled against ethereal monsters or monsters with damage reduction, yet with CR far below their level. Additionally, such restrictions won't affect all characters equally—a 3.5-era sorcerer, for instance, can operate just fine despite absolute poverty, while a fighter will really feel the lack of a level-appropriate magic sword. Monks, despite not using weapons or armour, are ironically among the classes most dependent on magic items because of their dependency on multiple ability scores.

Determining whether your system assumes money as character power may not be immediately obvious, but as a GM, it is crucial that you find out. D&D's modern-era spinoff, D20 Modern, does not use money as character power, as you can't simply buy better and better guns as you level up—once you've realized that the FN 5-7 pistol and the HK G11 rifle are mathematically the best guns and you've bought them (which you can easily do as a first-level character), you're set for the rest of the campaign. However, D20 Modern variant campaign settings, such as D20 Future and Urban Arcana, do allow you to directly convert money into character power, as the reintroduction of D&D-esque magic items of Urban Arcana and the "build your own gear" gadget-system of D20 Future allow unlimited wealth to be converted to unlimited power.

What to Watch as a GM: Ensure a steady trickle of monetary rewards that increase as the players level, realize that players will be increasingly antsy to reach town the more treasure they have, keep an eye on any game-provided wealth-by-level suggestions, and be wary about player-driven "get rich quick" schemes and item crafting systems. Be very cautious about allowing a PC to borrow money from an in-world bank or other lender, as they could quickly invest that money in magic items and destabilize the game balance.

Advantages: Combing through books to find perfect magic/sci-fi items is very appealing to some players, and it allows the GM to dangle money in front of his or her players to hook them on adventures.

Disadvantages: Can lead to very hurt feelings (and huge game imbalances) if a character is robbed/disarmed in–game, as it is functionally equivalent to erasing a feat from their character sheet. Further, the game can break down very quickly if there is a wealth disparity among the party, as there are more than simple roleplaying repercussions to playing a "rich" or "poor" character. Some players find this system "video gamey," and others feel that it overwhelmingly encourages players to steal everything not nailed down.

Best For: Combat-heavy games in which a "build" is important, high magic/soft sci-fi settings.

Money as Narrative Power

When money sees its most use bribing officials, hiring mercenary armies, building castles, or funding large-scale operations of any kind, money in your system directly converts to "narrative power." Players can use cash to influence the game world and the direction of the story, but not necessarily to deal more damage in combat (or heal more, or buff more, or whatever). This is where D&D 5e tends to get to after low levels (see "Crossing the Streams" for more on this). Many gritty, film noir-esque stories rely on key characters being dangerously in debt and are called to adventure by motivation to pay off said debt. Depending on the details of the campaign world, however, Players might stop caring about money entirely if it doesn’t directly relate to the plot or some kind of scheme.

What to Watch as a GM: If you come from a legacy of "Money as Character Power" games, you might have to remind yourself to loosen your grip if one or more characters seems to be accumulating "too much" money. Just because money doesn't have direct applications in combat and adventuring doesn't mean it isn't an important game resource—be sure to provide opportunities for players to use their money to solve problems, or else they'll quickly ignore it entirely.

Advantages: Allows a host of narrative options restricted by "Money as Character Power" games, such as managing businesses, organizations, or fiefdoms. Allows a wealth disparity between party members with only moderate issues. Additionally, allows stories involving borrowing and lending money without breaking balance in half, and overall can feel quite freeing.

Disadvantages: Can still cause problems if one PC is notably wealthier or poorer than the rest, depending on the players themselves, as they might end up driving the story. Unless finances are baked into the plot, using money as a reward is unlikely to garner much interest on behalf of the players.

Best For: Gritty realism, power politics, games that will eventually result in characters becoming lords/ladies/CEOs/etc.

Money as a Skill

In some ways, this is the exact opposite of "Money as Character Power"—when money is treated in your system as a skill, players have to sacrifice combat power in exchange for wealth. For instance, in the Fate-based Dresden Files RPG, if a player selects Resources to be one of their better skills, they are consciously giving up choosing, say, Weapons or Fists as a good skill. In such a system, a character's wealth is abstracted, and largely unaffected by major purchases or sales. Similarly, monetary quest rewards are pretty much off the table unless similarly abstracted.

This system strongly encourages huge disparities in wealth between party members, allowing rich and poor characters to solve problems equally well, just in different ways.

Note that "Money as a Skill" doesn't just mean that purchases are handled by skill checks, but rather that the wealth of a character is as core, internal, and untouchable as their other core stats, like Strength, Agility, etc. D20 Modern uses a system similar to skill checks to handle finances, but a character's Wealth score fluctuates hugely when they buy or sell things, so doesn't entirely fit in this paradigm.

Sometimes these systems do away with money altogether, such as the mecha rpg LANCER, which exists in a post-scarcity world entirely without money. Equipment is earned by getting progressively better "licenses," which authorize PCs to replicate increasingly powerful weapons and mecha shells.

What to Watch as a GM: You'll have to find ways to motivate players without monetary rewards, and be sure to find opportunities to reward players who invested in their "money" skill, either through narrative or scenario design, just as you would ensure to place a few traps in every dungeon for a rogue to disarm.

Advantages: Allows (and, indeed, almost requires) large wealth discrepancies between characters, and greatly reduces bookkeeping.

Disadvantages: Tends to be highly abstract, which can lead to a mismatch of expectations (such as if players start looting bodies to sell, with absolutely no mechanical impact, or being unsure if "+5 wealth" is middle-class or Bezos-class).

Best For: Narrative games without much focus on accumulating wealth and treasure, but in which money still matters.

Money as XP

This is the oldest of all old-school approaches, and in many ways the logical extreme of "Money as Character Power." When money is used as XP, acquiring gold directly leads to characters increasing in level. Sometimes this requires spending the money (i.e., donations to charity, training, or spell research resulting in XP gains), while other times, it only means acquiring the money (in which case, you have to answer the question of what players are to do with all this accumulated wealth after its primary purpose—giving them XP—has been achieved). This approach has largely been left by the wayside, and many modern players will discount it out of hand, but I'd encourage you to stop and think about it: we already accept that fighting more powerful monsters and overcoming more difficult challenges lead to greater XP and greater material rewards, so why not cut out the middleman and just say the material rewards are XP? One caveat is that, even moreso than with "Money as Character Power," this can result in PCs doing anything to get their hands on cold, hard cash—but, conversely, by removing (or downplaying) combat XP, it can also result in encouraging peaceful or stealthy approaches to solutions. This would lead into a whole conversation about when and how to give out XP, and what behaviours this decision encourages around the tabletop, but such a discussion is outside the scope of this essay.

This system works well for GMs that want their players to be treasure-hungry, like in Money as Character Power, but don't like the inevitable proliferation of magic items that results.

As with "Money as Character Power," under such a paradigm, GM's must keep a close eye on PC's pocketbooks. Taking away their treasure, either through in-game theft, a rust monster, or similar, will lead to frustration and hard feelings. Similarly, anything that lets players turn a profit without adventuring, such as item crafting or simply by getting a day job, could destabilize the game unexpectedly—many systems specify that only treasure found while adventuring counts towards XP, though determining what counts as "while adventuring" can be something of a headache (albeit not an insurmountable one). Additionally, this system strongly discourages wealth imbalances between PCs, as they directly result in some PCs being higher level than others.

Given how out-of-style this is in tabletop games, it's perhaps surprising that several modern video game RPGs fall into this category in the late game. In Skyrim, for example, after I'd bought the best weapons and armour that could be found in shops, future resources went into buying all the world's iron and leather to grind up my Smithing skill again and again, giving myself easy levels.

What to Watch for as GM: Same as with "Money as Character Power."

Advantages: Eliminates post-battle XP calculation entirely, encourages players to avoid direct confrontation, and gives players a very strong monetary motivation (which can also be a disadvantage) without resulting in a high-magic world.

Disadvantages: Can strike some players as unintuitive, and strongly encourages desperate treasure-hunting (which can also be an advantage).

Best For: Games involving treasure-hunting and exploration.

Money as Oxygen

With Money as Oxygen, money becomes something that players need a steady stream of just to survive. Maybe they're deeply in debt, have to make rent payments, have to maintain their equipment, or just have to feed themselves. The reason for their regular thirst for wealth might be narrative (rent, debt, etc.) or mechanical (equipment maintenance, etc.) in nature. In Traveller, a huge source of motivation for the party is just trying to keep ahead of mortgage payments for your starship. Money becomes the same as food, water, and air—a vital necessity that you simply always need more of.

With Money as Oxygen, players constantly have to eye their dwindling bank accounts and do cost-benefit calculations before accepting a mission, or else disaster could strike. This is a very, very different genre from "Money as Character Power" or even "Money as Narrative Power," as it rarely results in the party spending their money on anything other than survival. Unless they really hit a gold mine, they won't use money to upgrade weapons or armour, or to buy land and power, because doing so runs the risk of starvation/bankruptcy/etc.

This probably isn't the paradigm to use for most D&D-esque campaigns, as it can (and should) result in players actively avoiding heroic archetypes—if survival depends on a paycheck; the crusade against evil is someone else's problem.

What to Watch for as GM: This paradigm is bookkeeping-heavy, so make sure the players understand that from the get-go. Also, anyone expecting "Money as Character Power" might find themselves frustrated by their ever-dwindling resources. Make sure you have a very good handle on the math of the players' survival (that is, exactly how many gold pieces/dollars/credits they need to survive a week) or you might accidentally underpay them and lead them to ruin. Not that this shouldn't happen; it just shouldn't happen by accident. If you accidentally give them too much money, feel free to timeskip ahead several months until they're broke again, or dangle another moneysink in front of them, like a one-of-a-kind, now-or-never opportunity to buy a shiny magic item or spaceship upgrade (dipping judiciously into Money as Character Power).

Advantages: Makes the players feel poor, desperate, and downtrodden.

Disadvantages: Both the players and the GM have to keep a very, very close eye on finances in order to maintain tension. If paired with a mechanical system that doesn't result in substantial character progression from XP (such as skills, feats, etc.), then players can feel stuck and lacking motivation.

Best Used For: anything that can be accurately described with the words "seedy underbelly."

Money for Nothing

We've all played games in which money is straight-up useless. In many Zelda games, for example, like the classic Ocarina of Time, monsters drop rupees all through the game. In addition, there are secrets, hidden chests, and puzzles that pay out rupee rewards as if the game thinks they would make you happy. After the first hour of the game, it becomes blindingly obvious that there's no point to this money, as the things you would buy (arrows, sticks, bombs) are just as freely dropped from monsters and bushes. Many other video games hit this point after the early game as well (like Diablo II, where monsters continue to drop thousands and thousands of gold throughout the game, but there's nothing worthwhile to spend it on).

I personally can't see any advantages to this system, as I don't think it's chosen by design.

Crossing the Streams

Of course, few games fall strictly into one of the above categories, and most aim to do two or even three, which can lead to some common pitfalls. For example, the 3e splatbook the Stronghold Builder's Guide allowed players to spend tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of GP on elaborate castles and mansions. These was very cool, and the rulebook is one of my favourites from the edition… but I've never seen it used in actual play, because any player who did so would find themselves handicapped for the remainder of the campaign, as they hadn't invested their gold in magic items, as the system requires you to. (Again: the math of monster design in 3.x assumes and requires that player characters gain magic items at a set rate).

Some of the paradigms play nicer with each other than others. For example, many variants of "Money as XP" practically require a secondary output for money. Unless the XP is only gained by spending the money, all of that accumulated loot has to go somewhere—typically either into magic items (Money as Character Power) or into strongholds (Money as Narrative Power). Games that have large-scale battle rules (which, I've been told, ACKS does, though I haven't played it firsthand) blur the lines between Narrative and Player power, because the castles and hirelings a player buys actually do something, mechanically, though they typically don't help you in an actual dungeon. "Money as Oxygen," similarly, may require temporarily dipping into another paradigm to bleed off surplus money from the party to keep them permanently poor (something Traveller does gracefully by allowing incredibly-expensive spaceship upgrades).

The Full Plate Threshold

The Full Plate Threshold: once the players have bought the most expensive item available to them, the nature of money permanently changes.

One very common dynamic is for games to have Money as Character Power in early levels, and transition to another paradigm (or fall into Money for Nothing) at later levels. This is particularly common in video game RPGs, where after the early game, nothing anyone sells in stores is of any value whatsoever (or if they do, the price is trivial), yet despite this, monsters continue to drop thousands upon thousands of gold. If these games have a multiplayer aspect, players usually settle on a rare item as the de facto "currency" for trades.

This is also the dynamic that results when the sale of magic items in D&D-esque games is restricted, as in early levels, players save up to buy half-plate to replace their breastplates, warhorses to replace their feet, composite bows to replace their shortbows, and so-on. Once the most expensive upgrade has been bought (in D&D, the last character to make this transition is typically the fighter, as the best mundane armour available is a steep 1,500 GP in 3.x and 5e—a friend of mine dubbed this the "Full Plate Threshold" after my 5e paladin bought full plate, and we all suddenly stopped caring about gold), money is no longer convertible to Character Power. At this point, which can happen between level 3 and 7 depending on character class, system, and GM generosity, the nature of money in the campaign will change. This could result in the widening of scope in the campaign, as players invest in land, armies, and castles, or it could result in money piling up like in Diablo or Final Fantasy, totally meaninglessly. Similarly, many campaigns that start with "Money as Oxygen" can escalate into "Money as Narrative Power" as players finally hit the jackpot, and no longer need to worry about maintenance/mortgages/etc.

As a GM, handling this transition can be tricky. If it sneaks up on you without realizing (many 5e D&D GMs might not know (because they weren't told), for instance, that the nature of money changes dramatically the second someone buys full plate), they might suddenly find their players disinterested and bored around the table even though seemingly nothing else has changed. Their adventures are just as gripping, their monsters just as scary, their dungeons just as unique... but the players seem to be just going through the motions If your system or campaign doesn't have an endless supply of increasingly-expensive bits and baubles for players to buy, you're going to have to manage this transition, whether you want it or not.

Wrapping Up

There is no objective "right" or "wrong" way to handle money in an RPG, but some methods definitely work better for certain genres than others, as changing the "rules" of money in your campaign will massively change the feel and pace of the game. On the same note, be careful of follow-on effects from changing the rules: simply saying "magic items can't be bought," without making any other changes, will lead 3.x campaigns into a series of very predictable roadblocks (weakening martial characters, unevenly and unpredictably increasing encounter difficulty, and potentially eliminating motivation to go on some adventures) that you have to have solutions to. Similarly, adding a "magic item store" to a system not initially designed for it, such as D20 Modern, can lead to massive imbalance and weird behaviour. For instance, due to bizarre math, even relatively powerful magic daggers fall below the threshold at which rich characters lose wealth points in that system, making them literally free, while buying an unenchanted, off-the-shelf AK-47 (which is just above that same threshold) permanently drops the wealth bonus of any character. This leads to the system incentivizing any problem that can be solved with thousands of +3 Daggers being solved with thousands of +3 Daggers in a way that neither GMs nor (I assume) game designers intended.

These incentives matter. If a game penalizes one option and incentivizes another, that second option is just going to be taken more often. Maybe a lot more often. If you can align your campaign's incentives with desired behaviour for your players, you'll save a lot of headache, frustration, and counter-intuitive behaviour for everyone involved.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

(I’m not very fluent with the mechanics of Tumblr’s UI, and I’m not sure if “reblog” is the accepted way to respond to this message or if there’s another convention. Also thank you for your compliment!)

I think in my scenario I proposed, the assumption would be that, sometime between the end of the previous session and the start of the next one, the ship returned to home base. You’re right that it brings up a whole host of problems to always have the game start in the same port, not the least of which is that the systems furthest from it may never be visited. These are... pretty big problems, actually, with no easy solution. Drat.

Mongoose Traveller has the same property as classic in that FTL communication doesn’t exist outside of physically carrying mail on spaceships.

I think your ‘away team’ solution is a good one that could definitely work for a lot of groups, but isn’t quite what I’d be looking for--it would require a VERY large spaceship (most that I’ve seen have a crew of 5-10 or so; you’d need two or three times that to have a real ‘stable’ of characters onboard) and it would bring up a couple of issues in play that would be hard to resolve (i.e., “we’re down on this Vulcan planet and it sure would be helpful if Spock was here but he’s... busy... up in space, I guess? He’s taking his PTO?”)

I think we’re circling around something really promising, but I haven’t quite been able to align these pieces satisfactorily.

Parties vs. Guilds

(This is a gaming post, not a politics / economics post.)

So the last D&D game that I ran hit a scheduling conflict, then another, and then stalled to a halt. And in the meantime I started up a Pandemic Legacy game (which goes much faster when you play 3 games per session and one session per week :P ), backed a game that’s reminiscent of Darkest Dungeon (The Iron Oath, 39 hours left in their KickStarter at time of writing), and a friend got into Massive Chalice.

All of which have me thinking about the difference between RPG management / strategy games and tactics games. For example, Massive Chalice has the XCOM flavor where there’s a strategic layer and a tactical layer, which reinforce each other; Darkest Dungeon is similar while the strategic layer feels more lightweight. And in Pandemic Legacy, the strategic layer is basically the durable changes to the board/character/rules.

I notice that when I’m playing D&D, I miss that, and so I often try to bolt something like that on. When DMing, rather than having a specific antagonist and a specific plot (”okay, this particular villain running an evil organization is trying to accomplish this specific goal that the party will now have to thwart”) I’d rather make a world with a bunch of competing organizations and let the party go nuts. (This sometimes has the downside of them picking a different faction than I had hoped–no, worship the Apollo stand-in, not the Thor stand-in!–but that seems better from a group satisfaction point of view.) And this is also typically the sort of thing that I want as a player–put me in charge of a company that’s trying to get rich and powerful and has a team of professional murderers to solve problems for it, rather than have me chase down some nut who’s out to destroy the world.

But, of course, D&D by default isn’t set up for that sort of thing. (I’m remembering the time when we had a mission to clear a magical disturbance out of a section of forest so it could be logged, and I wanted to buy up the land for cheap first, since we had several thousand gold sloshing around; the DM said “basically, sure you can do that, but you’re not going to get any richer than the wealth-by-level guidelines.” Which is a sensible position–the point of the wealth system in D&D is to give players a sense of reward and points with which to customize their abilities, and having the players turn into merchants / focus on financial schemes and arbitrage rather than dungeon delving is losing the plot / stressing the system seriously. (I mean, imagine if your maxed-Persuasion character decided to start a Ponzi scheme in a world both 1) not particularly financially literate, and thus not particularly resistant to that sort of thing and 2) where those sorts of exponential returns could in fact be delivered by an adventuring party robbing dragons or similar things.)

Another problem that often happens is that people like having lots of character designs. They’ll make a character, play with it for a few sessions, and then think of something else cool they’d like to be. Or perhaps the character will get tactically stale–sure, being an archer is fun, but do you really want to spend twenty sessions as an archer? “Oh, now I get to attack twice in a round!” This leads to a conflict between character arcs and attachment and novelty.

Somewhat connected, trying to get a group of adults to all be available at the same time is remarkably difficult. (Gone are the days when my friends all went to the same school and had vacations at the same time and we could just walk home together and play D&D on Fridays.) When the sessions are highly linked, or the party is traveling together, this leads to bizarre situations where characters are ghosted, absent, ill, or whatever. Some games solve this by being bizarre themselves (in RIFTS, for example, you could just say that a rift swallows a character for that session). But then does the character get experience? A cut of the treasure? If someone being run by the party dies, what happens, especially if it’s a permadeath game?

But if instead of a single party of four people, the players are running a guild of, say, a dozen people that only sends ~4 out on any particular mission, then this works out fine. (Basically any game with a roster works this way.) The number of people you can send depends on the number of people who show up that week (but, if people are comfortable running multiple characters, doesn’t have to be a hard cap). Also include assignments for the people not on the mission, and then when Bob is absent, Bob’s wizard is busy doing something off-screen, like studying or making potions or whatever.

So I expect the next game I run to embrace that aspect from the start. But there’s still a fairly deep uncertainty about what to try to build off of–if there isn’t anything built for this yet, there isn’t going to be anything balanced for this yet / I can’t rely on other people’s design work instead of my own.

The ramping of D&D feels mostly wrong (roughly linear power scaling means sending lvl5 chars on missions is hugely different from sending lvl2 chars on missions, whereas swapping a different character into a Pandemic Legacy game is only slightly different) and the characters seem to have way too much specialization for them to be easily handed off. In Pandemic Legacy, you only need to learn a new special ability to play a different character; in Darkest Dungeon, you only need to understand four abilities to play a different character, and a roughly similar thing is true for Massive Chalice.

Those suggest something like just using Darkest Dungeon’s rules, or a small team minis game like Warmachine or Mobile Frame Zero. (Other contenders: Massive Chalice, XCOM, Fallout Tactics, Renowned Explorers, The Curious Expedition.) The basic things you want from a character are (1) biographical / psychological details, (2) skill / out of combat abilities, and (3) in combat abilities, and ideally all of them together fit on an index card (but an index card for each third might be fine, and it’s also alright if it refers to off-card stuff that the players can be reasonably expected to memorize).

(For example, in Darkest Dungeon, those things are: (1) name/color, (2) traits, campfire abilities, inventory, and trap finding (3) traits, abilities, equipment, hp, and stress. Basically everything fits in class 3, and a similar thing will be true for XCOM and Massive Chalice and so on. For D&D, each of them is considerably deeper.)

Another thing that’s nice about putting it in a reference class with, say, Legacy games is that you can ‘unlock’ new mechanics as you go along or modify existing ones with less of an objection. “Alright, guys, now all characters have ‘stress’ to track along with hit points.” or “This particular spell works differently now.” It makes using a work-in-progress system much more palatable.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love this. As I’ve been playing Traveller recently, I’ll add that Traveller would make a very good “Guild” game (the “Guild” is a small corporation that has *one* spaceship plus a stationary headquarters, so every session, a crew for that *one* spaceship is assembled and sent out. The fact that there’s only one ship justifies the fact that only a few people go out at a time.

Parties vs. Guilds

(This is a gaming post, not a politics / economics post.)

So the last D&D game that I ran hit a scheduling conflict, then another, and then stalled to a halt. And in the meantime I started up a Pandemic Legacy game (which goes much faster when you play 3 games per session and one session per week :P ), backed a game that’s reminiscent of Darkest Dungeon (The Iron Oath, 39 hours left in their KickStarter at time of writing), and a friend got into Massive Chalice.

All of which have me thinking about the difference between RPG management / strategy games and tactics games. For example, Massive Chalice has the XCOM flavor where there’s a strategic layer and a tactical layer, which reinforce each other; Darkest Dungeon is similar while the strategic layer feels more lightweight. And in Pandemic Legacy, the strategic layer is basically the durable changes to the board/character/rules.

I notice that when I’m playing D&D, I miss that, and so I often try to bolt something like that on. When DMing, rather than having a specific antagonist and a specific plot (”okay, this particular villain running an evil organization is trying to accomplish this specific goal that the party will now have to thwart”) I’d rather make a world with a bunch of competing organizations and let the party go nuts. (This sometimes has the downside of them picking a different faction than I had hoped–no, worship the Apollo stand-in, not the Thor stand-in!–but that seems better from a group satisfaction point of view.) And this is also typically the sort of thing that I want as a player–put me in charge of a company that’s trying to get rich and powerful and has a team of professional murderers to solve problems for it, rather than have me chase down some nut who’s out to destroy the world.

But, of course, D&D by default isn’t set up for that sort of thing. (I’m remembering the time when we had a mission to clear a magical disturbance out of a section of forest so it could be logged, and I wanted to buy up the land for cheap first, since we had several thousand gold sloshing around; the DM said “basically, sure you can do that, but you’re not going to get any richer than the wealth-by-level guidelines.” Which is a sensible position–the point of the wealth system in D&D is to give players a sense of reward and points with which to customize their abilities, and having the players turn into merchants / focus on financial schemes and arbitrage rather than dungeon delving is losing the plot / stressing the system seriously. (I mean, imagine if your maxed-Persuasion character decided to start a Ponzi scheme in a world both 1) not particularly financially literate, and thus not particularly resistant to that sort of thing and 2) where those sorts of exponential returns could in fact be delivered by an adventuring party robbing dragons or similar things.)

Another problem that often happens is that people like having lots of character designs. They’ll make a character, play with it for a few sessions, and then think of something else cool they’d like to be. Or perhaps the character will get tactically stale–sure, being an archer is fun, but do you really want to spend twenty sessions as an archer? “Oh, now I get to attack twice in a round!” This leads to a conflict between character arcs and attachment and novelty.

Somewhat connected, trying to get a group of adults to all be available at the same time is remarkably difficult. (Gone are the days when my friends all went to the same school and had vacations at the same time and we could just walk home together and play D&D on Fridays.) When the sessions are highly linked, or the party is traveling together, this leads to bizarre situations where characters are ghosted, absent, ill, or whatever. Some games solve this by being bizarre themselves (in RIFTS, for example, you could just say that a rift swallows a character for that session). But then does the character get experience? A cut of the treasure? If someone being run by the party dies, what happens, especially if it’s a permadeath game?

But if instead of a single party of four people, the players are running a guild of, say, a dozen people that only sends ~4 out on any particular mission, then this works out fine. (Basically any game with a roster works this way.) The number of people you can send depends on the number of people who show up that week (but, if people are comfortable running multiple characters, doesn’t have to be a hard cap). Also include assignments for the people not on the mission, and then when Bob is absent, Bob’s wizard is busy doing something off-screen, like studying or making potions or whatever.

So I expect the next game I run to embrace that aspect from the start. But there’s still a fairly deep uncertainty about what to try to build off of–if there isn’t anything built for this yet, there isn’t going to be anything balanced for this yet / I can’t rely on other people’s design work instead of my own.

The ramping of D&D feels mostly wrong (roughly linear power scaling means sending lvl5 chars on missions is hugely different from sending lvl2 chars on missions, whereas swapping a different character into a Pandemic Legacy game is only slightly different) and the characters seem to have way too much specialization for them to be easily handed off. In Pandemic Legacy, you only need to learn a new special ability to play a different character; in Darkest Dungeon, you only need to understand four abilities to play a different character, and a roughly similar thing is true for Massive Chalice.

Those suggest something like just using Darkest Dungeon’s rules, or a small team minis game like Warmachine or Mobile Frame Zero. (Other contenders: Massive Chalice, XCOM, Fallout Tactics, Renowned Explorers, The Curious Expedition.) The basic things you want from a character are (1) biographical / psychological details, (2) skill / out of combat abilities, and (3) in combat abilities, and ideally all of them together fit on an index card (but an index card for each third might be fine, and it’s also alright if it refers to off-card stuff that the players can be reasonably expected to memorize).

(For example, in Darkest Dungeon, those things are: (1) name/color, (2) traits, campfire abilities, inventory, and trap finding (3) traits, abilities, equipment, hp, and stress. Basically everything fits in class 3, and a similar thing will be true for XCOM and Massive Chalice and so on. For D&D, each of them is considerably deeper.)

Another thing that’s nice about putting it in a reference class with, say, Legacy games is that you can ‘unlock’ new mechanics as you go along or modify existing ones with less of an objection. “Alright, guys, now all characters have ‘stress’ to track along with hit points.” or “This particular spell works differently now.” It makes using a work-in-progress system much more palatable.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 4: Random Encounters

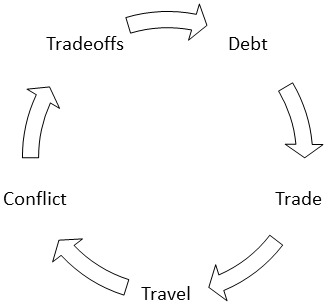

In part 1 of this series, I described how Mongoose Traveller's spaceship mortgage rule becomes the drive for adventure and action in a spacefaring sandbox, and the 'autonomous' gameplay loop that follows.

In part 2, I talked about how Traveller's Patron system gives the DM a tool to pull the party out of the 'loop' and into more traditional adventures.

In part 3, I talked about Traveller's unique character creation system, and how it supports the previous two systems, and how to avoid some of the pitfalls that I've seen in play.

In this part, I'll talk about how each of these three systems interacts with, and in fact, relies upon, Traveller's random encounters.

The Many Random Encounters of Traveller

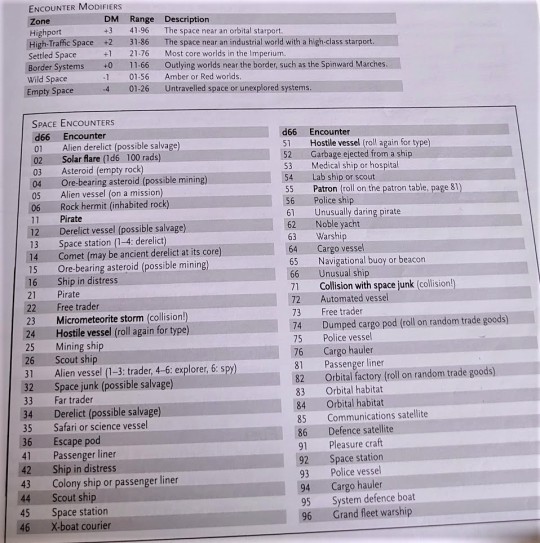

Traveller really takes the concept of random encounters and runs with it. Just in the core rulebook, there are random encounters for…

- Encounters during space travel (with different sub-tables for travel near a space port, in settled space, wild space, and so on),

- Encounters on foot in a starport, rural area, and urban area,

- Encounters with the law (that is, random legal complications tables for accidentally or deliberately breaking laws on strange new worlds)

There are also several 'honorary mention' tables that interact with the random encounter tables, such as:

- Random asteroid and random salvage tables,

- Random passenger tables,

- Random "bounty hunters come to repossess your ship if you didn't pay your mortgage" tables

- Full random monster generator tables—this one is particularly impressive. When an alien 'animal' is encountered, rather than having hundreds of pages of animals, it seamlessly moves into generating a fully-unique animal on the fly

- Random patron tables (these are truly in-depth: they generate who your patron is, what you're asked to do, random targets for your mission, and even who the opposition is).

- A random piracy table (unfortunately buried in the spacecraft chapter, not near the table where pirate encounters are rolled), that provides inspiration for just how the pirates manage to get the jump on the party and what they want.

- Of course, special mention goes out to the procedural subsector generator which is a full chapter in the book, in which the DM can generate the entire setting for the campaign.

What's impressive about Traveller isn't so much the volume, or even the quality, of the random tables, but how tightly they're tied into each of the other game's systems

Space Encounters

As Traveller is a game primarily about space travel, I'll focus on the Space Encounter table.

Sorry for the janky photo; I don't have the book on pdf. (Traveller Core Rulebook, 2008, p139)

This table is rolled on pretty much whenever the DM feels like it (the rules say: "roll 1d6 every week, day, or hour depending on how busy local space is. On a 6 […] roll d66 on the table below"). Many of these results tie in to subtables (any result of salvage, collision, mining, trade goods, or patron has additional rolls), but the photo above contains the most important part of the space encounter system.

Compare this table to the one from D&D's Manual of the Planes I used as an example in my series on wandering monsters:

Manual of the Planes, 2001. p. 151

Now, obviously, D&D's encounter table here is for an explicitly dangerous place—literally Hell—but the only result you can roll on the table that doesn't immediately move to combat is "72: Mercane trading mission." Thus, any time this table is rolled, there is a 99% chance of initiative being rolled.

Traveller's random encounter table marks its "unavoidable" encounters in bold (typically they're ones that immediately start a battle or some kind of dangerous phenomenon like a collision), though "patron" is also on there. There are only 7 results that are bolded this way, and only 6 of them are explicitly dangerous. Some of the non-bold rolls can result in battles as well depending on the party's actions, but there's no assumption of violence.

This is representative of most of Traveller's random encounter tables: they're not, by and large, random battle tables, but universe simulators. Depending on the context of the adventure, this means the random space encounter table could mean one of a number of different things. For example:

- If the players are pirates, this becomes a random pirate target table. Most of the results are unarmed NPC ships that would be perfect targets for piracy. However, some are police or military vessels that would cause real problems for the party.

- If the players are blue-collar miners and salvagers, this becomes a random treasure table, where the various derelict, asteroid, and salvage options become possibilities for work.

- If the players are in trouble (suffering from a medical emergency or a mechanical failure), this becomes a random rescue table, where you get to find out who answers your distress beacon, and what their intentions might be. Additionally, the tables tell you how long it takes for rescue to arrive (for example, in lightly inhabited space, you have a 1-in-6 chance every week that a spaceship shows up. At that point, you're running up against hard limitations of fuel reserves on your ship as to whether life support will give out before rescue arrives)

- If the players are simple traders, this table is a random flavour table, mostly adding a bit of flavour to the world while only occasionally having major impact on play.

"That's all well and good," you say, "but what does this have to do with tables?"

Encounters and Mortgages

Even with the bank taking most of the party's trade profit, without close attention to random encounters, the 'trade loop' can quickly turn into a 'roll dice and watch numbers grow' game. In a single iteration of the trade system, a lot of random encounters are rolled:

- A Space Encounter in the origin system while flying to the 100-diameter limit (you can't safely use Traveller's FTL drives within 100-diameters of a planet),

- A Space Encounter in the destination system while flying to the world from the 100-diameter limit (in the case of a mis-jump, which lands you far from the target world, this can use the more-dangerous less-settled options on the encounter table),

- A Legal Trouble Encounter check upon docking with the new spaceport,

- One or more Spaceport Encounter checks while in the spaceport and picking up cargo.

- One or more Random Passenger rolls if passengers are picked up

That's four or more rolls on random tables just going from one planet to another. This means that what might otherwise seem to be a straightforward (and therefore boring) trading game becomes, in practice, a series of minor adventures and close escapes full of danger. Remember, any time a pirate is encountered, there's a real possibility the players will be forced to jettison their cargo, which typically represents all of their accumulated wealth. The stakes are very high.

These high stakes also provide motivation for your players to accumulate wealth beyond simply keeping the banks off their backs: ship-scale weapon systems are very expensive (in the millions of credits), but even one or two upgrades to a basic ship can give the party a huge leg-up against non-player ships (who usually fly unmodified ships lifted directly from the book).

Encounters and Patrons

Virtually every random encounter table has a one or two entries that result in the party meeting a patron, which, as I described in the second part of this series, are the keys to adventure in Traveller. Math isn't my strong suit, but back-of-the-napkin calculations suggest that around one-in-five trips between worlds will involve a run-in with a patron, and thus the start of a classic-style adventure. Note that while the book does provide tables to generate patrons, it really isn't practical to do this on the fly. What this does mean is that, as DM, when you have a free afternoon or just a couple of hours, you can create and queue up your own patrons in advance and trust that, at some point, the game's procedural universe simulation will put them in front of the party.

Encounters and Character Creation

Traveller’s character creation system is different. So different, in fact, that it can be tempting to cut it out altogether and replace it with something conventional.

The rulebook recommends that, if possible, patrons should be drawn from the PCs' existing contacts and allies. I don't think it explicitly mentions this, but hostile encounters should also often include the PCs' existing enemies and rivals. This ties player characters' backgrounds directly into the action of the game's 'present' timeline. In addition, it's actually much easier as DM to pull out a character that you already have in your rolodex sometimes than come up with a new, characterful pirate captain for each random encounter.

Missing Legs

Unless you really know what you're doing, Traveller runs a serious risk of collapsing if any of these four legs (mortgages/trade, patrons, character creation, and random encounters) is removed or seriously modified. Unfortunately, the game doesn't make this clear in any particular way, which is why my previous DM (who, again, is very good) struggled visibly with his two campaigns.

If you decide mortgages won't be a major aspect of the game, you have to remove or severely nerf the trade rules, or your party will be rolling in cash almost immediately. Because the trade rules are the primary motivation to move around (and thus, roll random encounters), you have to come up with another reason for them to do so. (Note that it's possible, during character creation, to be loaned a Scout Ship without having to pay mortgages on it. As DM, you should consider disallowing this, or at least be aware of the implications if this reward is rolled)

If you decide trading won't be a major aspect of this game, you have to find another way for the party to make money (lots of money) or they simply won't be able to pay their mortgage. You also have to find a reason for them to travel from place to place, or they won't be able to justify the cost of fuel, crew salary, and other expenses. The game will run serious risk of defaulting to jumping from one patron job to another. This isn't inherently bad, but it's a lot of work for the DM, and, at some point, becomes a railroad of quest-to-quest with no other real alternative. You're also cutting off the party from meaningfully interacting with the spaceship upgrade system—there's pretty much no other way to raise the millions of credits needed to buy extra laser turrets and stuff for their ship.

If you decide patrons won't be a major aspect of the game, you might find that the party never leaves their spaceship. Skills other than those related to trading and spacecraft operation will never be used, most of the equipment chapter and the encounters and danger chapter will be left unread, and those wild and unique planets you spent ages generating before the campaign will go completely unnoticed.

If you decide Traveller's character creation is too unbalanced and ought to be replaced by a point-buy system, you might struggle to weave the players' contacts, rivals, allies, and enemies into the campaign (if they even have those), and you might miss out on having hired NPCs running around on the spaceship. This in turn means that there's many fewer opportunities for roleplaying during travel. Additionally, your players might then operate with the expectation that Traveller will have anything resembling game balance, and, as such, be frustrated by the game's hugely uneven random encounters.

If you decide random encounters won't be a major aspect of the game, you might find that the party never meets a patron, never has the opportunity to engage in piracy, never has any trouble watching their credits climb and climb indefinitely, and never has much motivation to make money (and thus, go on adventures and travel around) beyond paying off their mortgage.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

i find it really surprising to read you write "For a D&D campaign, you usually come to the table with a more-or-less fully-fledged character concept" or "Traveller is very different from most D&D-esque RPGs. It doesn’t provide any guidance for or benefit from, for example, balanced encounters." I think of "spin the wheel and see what you get" chargen and "balance isn't even a consideration" as _emblematic_ of DnD--old school DnD. I feel like that's what DnD was _all about,_ once. (1/2)

Right, I probably should have mentioned this in the article. I personally started meaningfully playing D&D with 3.0 (I played 2e with a babysitter, but only dimly remember it). As a result, I can’t speak to pre-3.0 D&D with any authority, so when I say “D&D” I’m usually referring to 3.0e/3.5e/D20 modern/Pathfinder/5e. I largely gave 4e a pass; it wasn’t really “for me”.

From 3.0 on, striving (and often failing to achieve) balance in one way or another (between each party member, between party members and monsters, between choices of feats and weapons) has always been a major part of the game’s design. So for me, Traveller is really my first foray into an RPG that doesn’t even pay lip-service to balance. Frankly, it’s deeply refreshing. As you point out, it certainly isn’t a new idea overall, but it’s a new idea to me.

I hope you don’t mind me posting this publicly; I can take it down if you want. I think it’s a valuable tidbit of conversation that adds meaningfully to my posts on Traveller.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 3: Character Creation

In part 1 of this series, I described how Mongoose Traveller's spaceship mortgage rule becomes the drive for adventure and action in a spacefaring sandbox, and the 'autonomous' gameplay loop that follows.

In part 2, I talked about how Traveller's Patron system gives the DM a tool to pull the party out of the 'loop' and into more traditional adventures.

In this part, I'll talk about Traveller's unique character creation system, and how it supports the previous two systems.

Brief Overview of Character Creation

Traveller's character creation is weird, and it was the first thing house-ruled away by my old DM—and I can see why.

Traveller character creation is a minigame of sorts, in which you first generate ability scores (much like in D&D), then pick a career. You make a stat check to qualify for the career, one to 'survive' the career (more on this later), and one to advance. Every time you qualify for the career and/or advance, you get a random skill or stat boost from a table related to your training. In the Army and Marines, for example, you're very likely to get combat-related skills, while as a Merchant you're more likely to get something like Broker or Admin (which tend to be more useful, surprisingly).

You also roll once on a life event table, in which your character might fall in or out of love, make friends or enemies, study abroad, and so on.

You then advance four years in age and try again, and continue for as long as you want. If your character gets too old, they start suffering physical ability score consequences, though these can be bought off with semi-legal anti-aging meds, the consequence of which is starting with high amounts of medical debt.

Rolling to Survive

If you fail a survival roll, you're permanently expelled from your career (but can start another one), and often suffer major debilitating injuries in the form of sweeping permanent ability score damage, though this can be bought off by going deep into medical debt. It's technically possible to die in character creation if your physical ability scores are reduced to zero in this way, in which case you would start over. For that to happen, the player would have to decline treatment—basically, they're making a choice to give up and start over. This is a kind of extreme "safety net" against playing truly worthless characters, I suppose, though I haven't seen it happen yet.

Why is this Good Again?

This way of creating characters is shockingly different from any that I've seen before. The character that you end creation with might not have any resemblance at all to what you sat down and intended to create, which was a huge source of frustration, as a player, in my last two campaigns. It's more common than not to, for example, come up with a concept for a dashing space pilot and end up with a 98 year-old-that-looks-34 white-collar office worker who's got a laundry list of grievances against various corporations who have fired him over the years.

When I've seen this system work well, it's because players went into it with different expectations that they would in D&D. For a D&D campaign, you usually come to the table with a more-or-less fully-fledged character concept, then roll stats (or point-buy) and fill in the boxes. In Traveller, it's more like spinning a wheel and seeing what you'll get.

For the kind of campaign that Traveller assumes, however, this is perfect, and here's why.

First, it sets the tone of the campaign. Traveller is very different from most D&D-esque RPGs. It doesn't provide any guidance for or benefit from, for example, balanced encounters. By creating mechanically unbalanced, unpredictable characters, it is telling the players from the start that there are sharp edges to this game and they have to stay on their toes.

Second, it generates crucially important NPCs for the campaign. Those life events—and some fail-to-survive rolls—often create allies, enemies, rivals, and contacts: NPCs that are guaranteed to be met during the campaign. The book provides tips to the DM to ensure that these NPCs have access to spaceships, as they can be found on the random encounter tables. But here's the fun bit: the Player will be just as pissed at their rival, Captain Morgensen (or whatever) as their character is supposed to be, as he was (according to the events table) instrumental in getting them fired from their career as a space scout. By generating these characters during character creation's life-simulation, it gives them a real, emotional connection that leads to a lot of fun during play. These NPCs can easily function as Patrons (which, as explained in part 2, are the keys to adventure), or can provide paths to Patrons.

Third, it has the potential to start the characters massively in debt. The clear optimal path in character creation is to pay off any injuries by going into medical debt, and chug analgesic anti-aging pills like they're Skittles in order to keep advancing down your career paths, or start new ones. As explained in part 1, Traveller's 'loop' functions best when the PCs are swimming in as much debt as possible. The more debt, the more motivation to travel, and thus the more space pirates and space dragons and space princesses and whatever that they'll meet.

Fourth, it familiarizes them with the setting. The book provides quite a few career path options to the Players, and uses the same to generate its NPCs. Thus, just by reading through the career path options available to them, Players learn a lot about the world of Traveller and the kinds of people they might meet, without having to read lengthy setting handouts or pages and pages of lore or anything like that.

Fifth, it creates gaps in the party's expertise, which encourages hiring NPCs. It's virtually impossible to end up with an adventuring party that can cover every skill required to operate a spaceship, for example. This encourages hiring NPC crewmembers to fill in those gaps, which really helps make Traveller 'work'. A lot of the party's time is going to be spent on their spaceship, so the more people who are on there, the better from a roleplaying standpoint. Also,

That said, it's not perfect, as…

There Are Some Real Limitations

Mechanically, the main issue that's come up with Traveller's character creation is that it's entirely possible for the party to be missing one or more vital skills, or for a character to be lacking something that would be key to making them 'work'. Traveller's basic dice mechanics harshly penalize untrained skill checks compared to attempting even slightly-trained ones, and some roles can't be easily filled in by NPC crewmembers. If your character never rolls to learn the Gun Combat skill, for example, they'll more likely than not miss every attack they make in the whole campaign. The party can overcome this by hiring marines, for example, but the player might still be bored every time a gunfight starts.

This can be mitigated by, say, letting that player control their hired NPCs in combat directly, but as the game doesn't really provide a lot of guidance for who plays hired NPCs (the DM? the player that hired them? The party as a whole, by vote?), the DM and player will have to come up with their own solution. Since they might not even realize that there is a problem that needs to be solved, this can easily lead to traps (for example, if the DM assumes full control over hired NPCs, many battles will lead to the DM just rolling checks against himself/herself over and over in front of an audience) that generate frustration.

Mechanics aside, there are some narrative implications for character creation that might strike many Players as quite weird. Most D&D Players default to making their adventurers whatever their races' equivalent of early-20s is. Sometimes there's an old wizard thrown in to spice things up, but I'd say 9-in-10 characters I've seen are 'college-aged.'

Traveller strongly rewards old characters. Sometimes very old. Don't be surprised if the average age of the Traveller characters is the same as the summed age of all of your Players. This isn't necessarily bad—immortal, eternally-young sci-fi characters are kinda neat—but it's also pretty limiting, and may not be within the Players' expectations. If a Player wants to make a character who's a young hotshot just starting out, the rules will punish them severely. They'll have virtually no skills, no money (or debt!), no ship shares (units that track ownership of the spaceship), and no NPC connections.

Making it Work

I'm not going to change these rules until I'm more familiar with the system, but my gut says that many of the game's skills (such as Computers, Comms, and Sensors, or the two skills that govern two different, but similar, kinds of environmentally-sealed armour) could be consolidated to reduce the odds of a missing skill torpedoing a character. I also think flexibly passing back and forth control of hired NPCs between the DM and Players will solve a lot of problems, but deciding on the fly who is in control in a given scenario will probably take some experience as a DM. I’m vaguely aware that there’s a second edition of Mongoose Traveller, which may have done some of these things, but I haven’t played it and as such can’t comment on it.

I think for a satisfying experience, you have to make it clear to your Players not to try to build their characters to a pre-imagined concept, but rather come up with a concept as they play through their character's life. Also, tell them upfront that, in this particular sci-fi universe, anti-aging technology has allowed for the rich and powerful to stay eternally young, and that they can expect to have already retired from one or more full careers before the campaign even begins.

Next up, how this all ties in with random encounters.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 2: Patrons

In part 1 of this series, I described how Mongoose Traveller's spaceship mortgage rule becomes the drive for adventure and action in a spacefaring sandbox, and the 'autonomous' gameplay loop that follows.

In this part, I'll talk about the Patrons—questgivers—that are baked into Traveller's gameplay loop and provide opportunities for more 'traditional' (that is, pre-scripted) adventures.

Patrons

Patrons are, essentially, adventure hooks. The 'default' premise is that an NPC offers to hire the party for a job (the reward for which is scaled to the PC's spaceship's cargo hold, so is always competitive with trading for money making). The job rarely goes as planned, and the patron is rarely on the up-and-up, so various twists and turns are ensured as the party attempts to complete the job. These jobs usually require putting the trade 'loop' on hold and doing something else (in fact, they're virtually the only incentive to get out of your spaceship) and are basically the gateway to all gameplay that doesn't involve trading, pirates, and FTL travel.

"Patron" is literally entry in Traveller's random encounter tables, which provides a way for them to enter the campaign, but it's also the kind of thing that can easily just be included by the DM, regardless of what the table says.