Text

Research - Artistic Research

Excerpts from:

What is artistic research?

JULIAN KLEIN, What is artistic research?, Gegenworte 23, Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften 2010

WHAT IS ARTISTIC RESEARCH?

Research

According to the UNESCO definition, research is "any creative systematic activity undertaken in order to increase the stock of knowledge, including knowledge of man, culture and society, and the use of this knowledge to devise new applications." (OECD Glossary of Statistical Terms, 2008).

(...)

Research therefore means not-knowing, rather: not-yet-knowing and desire for knowledge (Rheinberger 1992, Dombois 2006). Research also seems to be no unique selling point of scientists, but to include many activities that have been made by artists, for example.

(...)

"Research about / for / through Art | Art about / for / through Research."

(...)

Even natural scientific research alone is very diverse in its objects, methods and products, as McAllister (2004) notes. How much more this applies to research including the humanities and social sciences, and further industrial, market or opinion research. Not surprisingly, this is also true for artistic research. Among the authors cited here, there is agreement that this diversity has to be preserved against efforts to canonical restrictions.

(...)

The principal diagnosis is, however, "research" in the singular exists not more than "science" or "art" - they all are collective plurals, assembling very different processes, which often are closer related to others over category boundaries, like disciplines, than with some other members of their own faculty, and then assemble much better under common interdisciplinary roofs, such as topics, methods or paradigms. This “urge of singularization” is probably the strongest root of the supposed and stubborn opposition between art and science: Baecker (2009) calls this the "organizing principle of the functional difference", which emerged in the 19th century according to Mersch & Ott (2007).

Art and science are not separate domains, but rather two dimensions in the common cultural space. (...) However, at least not everything, what is considered being art, has therefore to be unscientific and not everything that is regarded as science, inartistic.

Research is not only artistic, if carried out by artists (as helpful as their participation may be), but deserves the attribute “artistic”, when made under the specific quality of an artistic experience.

Artistic Experience

In the mode of aesthetic sensing perception is present to itself, opaque and sensible. Artistic experience can be determined similarly as the perception mode of sensible interfering frames (for details see Klein 2009). (...) The artistic experience as well as the aesthetic sensing are modes of our perception and, as such, constantly available, even outside of art works and art places.

In the experience the subjective perspective is constitutively included, because experience can not be delegated and only be negotiated intersubjectively in second order. This is a major reason for the conception of the singular nature of artistic knowledge (Mersch & Ott, 2007, Nevanlinna 2004, McAllister 2004, Busch 2007, Bippus 2010. Dombois 2006 points to Barthes' proposal of a "mathesis singularis" in 1980). Artistic experience is particularly dependent on and inseparable from the underlying undergoings. Artistic experience is an active, constructive and aesthetic process, in which mode and substance are fused inseparably. This differs from other implicit knowledge, which generally can be considered and described separately from its acquisition (see Dewey 1934, Polanyi 1966, Piccini and Kershaw 2003).

Artistic Research

If "art" is a mode of perception, "artistic research" must be the mode of a process. Therefore, there can be no categorical distinction between "scientific" and "artistic" research - because the attributes independently modulate a common carrier, namely, the aim for knowledge within research. Artistic research can therefore always also be scientific research (Ladd 1979). For this reason, many artistic research projects are genuinely interdisciplinary, specifically: indisciplinary (Rancière in Birrell 2008, Klein & Kolesch 2009).

Against this background the phrase "art as research” seems to be not quite accurate, because it is not the art, which evolves into research somehow. What exists, however, is research that becomes artistic - so it should be rather named "Research as Art", with the central question: When is Research Art?

In the course of a research, artistic experience can occur at different times, be of different durations and different importance. This complicates the categorization of the projects, but allows on the other hand a dynamic taxonomy: At what times, in which phases can be research artistic? First, in the methods (such as search, archive, collection, interpretation and explanation, modeling, experimentation, intervention, petition,...), but also in the motivation, inspiration, in reflection, discussion, in the formulation of research questions, in conception and composition, in the implementation, in the publication, in the evaluation, in the manner of discourse - in order only to begin the list hereby. These phases can be summarized only posthoc and categorize, for example in the usual triple of object, method and product. This sequence is important: for the discussion on artistic research is not to fall into a normative restriction in a canonical system (Lesage 2009).

At what level will the reflection of artistic research take place? In general at the level of artistic experience itself. This does not exclude neither an (subjective or intersubjective) interpretation on a descriptive level, nor a theoretical analysis and modeling on a meta- level. But: "It is a myth that reflection is only possible from the outside." (Arteaga 2010). Artistic experience is a form of reflection.

Artistic knowledge

Who are we? How do we want to live? What are things meaning? What is real? What are we able to know? When does something exist? What is time? What's a cause? What is intelligence? Where is sense? Could it all be otherwise? - These are examples of common artistic and scientific interest. Their treatment does not always lead to secure and universally valid knowledge (with regard to the history of science: only in very few cases, no?). The arts are granted the authority to formulate and address such basal and yet complex issues in their specific ways, which don’t have to be less reflected than those of philosophy or physics, being capable to gain specific knowledge that could not be delivered otherwise.

(...)

Some authors require that artistic knowledge must nevertheless be verbalized and thus be comparable to declarative knowledge (e.g. Jones 1980, 2004 AHRB). Others say it is embodied in the products of art (e.g. Langer 1957, McAllister 2004, Dombois 2006, Lesage, 2009, Bippus, 2010). But ultimately it has to be acquired through sensory and emotional perception, precisely through artistic experience, from which it can not be separated. Whether silent or verbal, declarative or procedural, implicit or explicit - in any case, artistic knowledge is sensual and physical, "embodied knowledge". The knowledge that artistic research strives for, is a felt knowledge.

____________________

Excerpt from:

Text: Angelika Boeck and Peter Tepe | Section: On “Art and Science”, What is Artistic Research? W/K Between Art and Science, A Peer reviewed online journal. February 25, 2021. Taken from: https://between-science-and-art.com/what-is-artistic-research/

1. Angelika Boeck: my understanding of artistic research

Since 1999 I have been carrying out research using the means and methods of my artistic practice. My dissertation, titled De-Colonising the Western Gaze: The Portrait as a Multi-Sensory Cultural Practice (2019), is also committed to this position. Artistic research is a broad field; it encompasses many different concepts. I prefer to use the term art practice-based research, as I consider it to be research founded on a particular art practice: firstly, on the artist’s activity in pursuit of a concrete question or a set of not yet clearly defined questions by employing artistic means and methods, and secondly, on the presentation of the process and/or outcome in the form of an artwork. The proximity to scientific strategies and practices lies in the “not-yet-knowing” (Klein 2011: 1); in the desire to show and understand; and in the fact that artists often use ethnographic, sociological, collecting/archiving or laboratory work practices; that they experiment with processes that produce images or deal with new media and technosciences (for example the Brazilian media artist and theorist Eduardo Kac, who manipulated living organisms according to aesthetic criteria as part of his Bio Art or Transgenic Art in the early 1990s). Thus, artistic research can be considered as a means of approaching human subjects (including oneself), objects and contexts (current or historical) — an examination often combined with an interest in gaining concrete experiences in an endeavour to convey these in a sensorially perceptible form (to incite reflection, amusement, disturbance or provocation). Artistic research is therefore not just a matter of analysing a given circumstance or certain emotions.

Reflection takes place during artistic production. Other forms of knowledge production (particularly in the natural sciences) require the use of approved methods, being part of a theoretical discourse and a verifiable, generalisable and comprehensible depiction of the research process. Artistic research functions differently: methodological and the theoretical aspects can often only be identified retrospectively, through a process of reverse engineering. This means that the creation process of the artistic works is examined and put in relation to the works of other artists, scientists and theorists in order to extract the components of which they are made. A written reflection of the artist (formulating the question, identifying the context and conditions, providing information on the method and theory, self-reflection) is possible, but not absolutely necessary; though I do consider it to be profitable.

_____________________

Excerpt from KabK, Lectorate Art Theory and Practice. Taken from: https://www.kabk.nl/en/lectorates/art-theory-and-practice/keywords/artistic-research

Artistic research is distinguishable from other forms of academic research by the central role of artistic practice. The research question derives from the artistic practice of the artist-researcher, the research methods are characterized by the use of artistic practice and materials, and the results of the research project contribute to both artistic practice (on an individual as well as on a more general level) and to artistic academic discourse. Because artistic research is carried out by artist-researchers this produces knowledge, experiences and understanding that cannot be obtained by any other means. They are manifest in the art works and the artistic practices themselves.

__________________

0 notes

Text

P1 - Portraits of a River

Class done in collaboration with tutors from the WdKA (Xenia, Mia and Eric) Practice 1 - 2024.

8 week duration

Assignment:

Objective: Create a visual narrative exploring the river Nieuwe Maas, encompassing its physical, metaphorical, and social dimensions through interdisciplinary research methods.

During this course, you will produce a new collaborative work in the form of a visual narrative* together with an interdisciplinary group of peers. Your visual narrative will explore the river Nieuwe Maas, encompassing its physical, metaphorical, and social dimensions. Your work will depart from a series of interdisciplinary research methods that will be addressed and discussed in class.

*A visual narrative or visual storytelling is a story told with visual material. You can use images, video, audio, text, performance or object-based materials to tell this story and/or convey a message.

Week 1: Introduction, context and team-building

In class:

Welcome, introduction of the course (and competencies/assessment criteria), its goals, timeline, and expectations, teachers. Icebreaker activities to help students get to know each other.

Students write their names and pronouns on papers

Introduction of Practices (film) + Natalia presents her work

Drawing Station Introduction

Group formation and introduce homework for next class.

By the river activity:

Look for suspicious things (objects, smells, colours, textures, shapes, movements, sounds, temperature etc.)

Document it and/or how could you document it?

Homework: Each student group gets a topic in connection to the Maas River they must research and present to the class in no more than 5 mins. Topics: history, geography, criminology, ecology, biology, urban planning, environmental damage over water quality, architecture, demographics, Economic and social impact of the river, water usage, cultural significance, hydrology, etc.

Week 2: Exploring diverse interdisciplinary approaches, understanding interdisciplinarity, intro to visual narrative

Natalia's Class:

10:30 – 13:15 Group A – Drawing Station

14:15 – 17:00 Group B – Drawing Station

Students share their skills and preferred methods of experimentation corresponding to their own field and discipline.

Students build their own catalogue of methods in the form of a zine/manual made in class.

Collaborative exercises where the students exchange and practice to entangle their ideas, styles, methods and skills by putting in practice their own manual (methods) by the Maas near WdKA.

10:30 - 10:45 (14:15 - 14:30): Sitting in their groups, students individually list the methods for conducting research that they practice in their own field. ex. Advertisement - target group study, Fine Arts - material research, Photography - site visits.

10:45 - 11:30 (14:30 - 15:15): As a group they discuss the lists and make one unified list that can be useful for their group project. They will name each method and provide a description of: 1) What it is, 2) How to practice it, 3) With whom to do it, 4) When it should be done, 4) What materials are needed to practice it, and 5) What are the possible challenges.

11:30 - 12:30 ( 15:15 - 16:15) : Make this list (catalogue of the groups research methods) into a zine.

12:45 - 13:15 (16:30 -17:00): Groups show their zine and group discussion.

Materials needed: (color) paper, magazines, scissors, glue, markers, pens, paint or colour pencils, erasers, sharpeners, staplers. (drawing and collage materials).

Homework: Students work independently and in groups on:

Students put in practice the research methods they consolidated as a group in the form of a zine at the Maas. They must document their process and findings.

Students print copies of their zine and bring it for our next class

Video: John Berger Susan Sontag (storytelling lecture) watch before Friday.

Week 3: Research through drawing, integrating research into creative process (research by making)

Natalia's class:

10:30 – 13:15 Group A – Drawing station and outside

14:15 – 17:00 Group B - Drawing station and outside

Introduction to artistic research

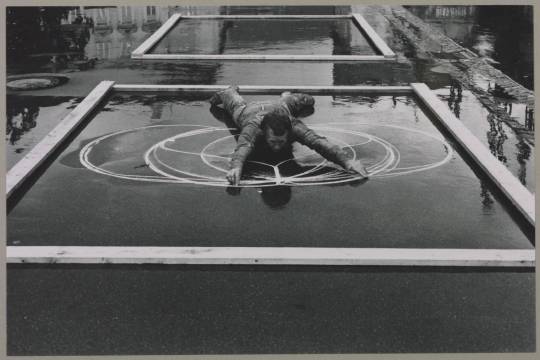

Embodied research exercises in location – Inspired by Sara Ahmed, Orientations: Toward Queer Phenomenology.

10:30 - 11:30 (14:15 -15:15): Read the Forward of Mika Hannula, Artistic Research Methodology.

11:30 - 12:45 (15:15 - 16:30): Out in the landscape

Choose on of the following exercises and allow your intuition to guide your experience, dont question it or try to make it rational or with an end. The keyword to this exercise is *Desire.

Descriptions: Walk around and make thorough descriptions of what you see. Don’t stand only in one location, if you have made the description of something, then move on to the next. Let your intuition determine what you want to describe. Record your descriptions. Think of words, situations or sounds that can help describe what you see and sense. Include them in your recording and narrations.

Acute listening: Tune in to the sounds of the landscape. Try to isolate the sounds from all other noise, so that you have clarity over its qualities. Imitate it, try to make the same rhythm, the same pitch, the same fade in/out. Record yourself + Walk around the landscape and make your body encounter other bodies (non-human) by touching, licking, laying on or under, standing on or under and listen to the sounds these encounters create. Record them. Record the sounds of the landscape and write down what sounds you are recording.

Choreograph of space and relation: Think of the movement that the space / location suggests to your body. If you follow your intuition in navigating the landscape and encountering other non-human bodies, what type of movements do you do in order to reach those encounters? + Think of the movements that would be habitual in that landscape and how they shape that landscape. Enact those movements and document them. Be wary of how your body is shaped and moved by the space. While enacting them change pace, change orientation, and enact the movements in different locations, document your experience and the impact of those shifts in writing, drawings or video.

Extensions of the body: Find objects, bodies or non-human bodies that can help your own body extend in the space. Practice these extensions and document them in writing, drawings or video. Reflect on their inherent agency, their power and impact over your body, your movements, your voice, your rhythm and the space around you. Write down or record your reflections.

and:

Collect: Gather a collection of everything you encountered. Keep these objects and bodies (matter) for the next class, you will need them. Document you collection.

*If taking an other-than-human-body or object hurts or damages something, then document it with a drawings or tracing its textures or describing it in sound.

12:45-13:15 (16:30-17:00): Group discussion: Show and discuss findings

Guide discussion around Desire: What is desire for me? How do I experience desire? How does desire mediate my relations with other bodies and objects? Write down your ideas, realizations, confusions, questions, etc.

Materials needed: phone - recording (audio/video/photo) device, notebook and pen/pencil.

Homework:

Students compile all the materials gathered during the session in physical form. If images were taken, sounds were recorded or videos were filmed, they must be printed or displayed in a device in the following session with Natalia.

Week 5: No Class with Natalia.

Week 4: Experimentation and making, with emphasis on experimental and collaborative process

10:30 – 13:15 Group A – at Drawing Station and WdKA

14:15 – 17:00 Group B – at Drawing Station and WdKA

Collaborative session in class: with all the material collected in the previous embodied research session.

Peer to peer review about material they collected + Group analysis of the material

Arranging, re-arranging and installing the material for public display (exercise) - improvising a narrative within a different context. (object-based, presenting archived material)

10:30 - 11:30 (14:15 - 15:15): In groups students share the collected material from the previous class and they do group a analysis of the material.

11:30 -12:30 (15:15 - 16:15): Each group will find a spot in the 3rd floor of WdKA (drawing station and around). They will arrange and re-arrange the material as a group improvising a narrative that is self-standing.

12:30 - 13:15 (16:15 - 17:00): We go around to see and discuss the results.

Materials needed: Materials collected from the previous class and installing material such as rope, tape, nails, etc.

Homework: Each student individually brings a news article about the Maas River in Rotterdam that they find relevant to their interests and/or project.

Week 6: Production of Visual narrative.

10:30 – 13:15 Group A - Drawing Station

14:15 – 17:00 Group B - Drawing Station

Collaborative session in location: Each student brings an article from the news about the Maas River. As a group they agree on a question(s) or topic(s) they would like to find out more about. Students conduct artistic research (conversation/interview) with the nearby inhabitants in order to gather testimonies on the topic.

Students analyze the interviews they conducted and how they may affect their project/knowledge of the Maas.

Discussion over the relevance, impact and value of art and design in the broader social and cultural context.

10:30 - 11:00 (14:15 - 14:45): Each student shares the content of the article they brought with their group. As a group they agree on a question(s) or topic(s) they would like to investigate further. Each group writes down the questions or topics.

11:00 - 12:00 (14:45 - 15:45): Students conduct interviews/conversations with people in the city near our chosen location. Students gather testimonies on that topic(s) or question(s).

12:00 - 12:45 (15:45 - 16:30): Students analyze the interviews/conversations they conducted and how they impact their stories, narratives, and knowledge of the Maas River.

12:45 - 13:15 (16:30 - 17:00): Group discussion about their findings.

Week 7: Refining the visual narrative, asking critical questions, production

Natalia's class:

10:30 – 13:15 Group A – Drawing Station

14:15 – 17:00 Group B – Drawing Station

Feedback session with groups and peers.

Asking critical questions.

Writing for 1.3

10:30 - 11:30 (14:15 - 15:15): Writing reflection for 1.3:

Choose 3 out of the 5 prompts below to write about. Write for 15 minutes on each prompt. Write in whatever way feels natural to you. You don’t have to write in an academic or literary format. You won’t be assessed on correct grammar or spelling; getting your thoughts on paper is what counts. Before you start to write, travel in your mind to moments and memories. Think about how you felt and where you felt it in your body. Think about your sensory experience: what did you see, hear, smell, feel, etc. Use these memories and experiences to be as detailed and elaborate as possible in your writing.

Describe an object you interacted with during P1.2 program.

Describe a moment during the P1.2 program where you experienced a shift in knowledge or learned something new.

Describe something unexpected you experienced during the P1.2 program.

Describe an experience from P1.2 that feels valuable to your future projects.

Describe a space outside of the Academy that you connected with during the P1.2 program.

Homework: Save your writing assignment as .docx. Upload the link to your assignment under the correct Station and student group (A or B). Deadline for submission is Thursday, March 28 at 23:59 (uploading is not possible after)

11:30 - 12:30 (15:15 -16:15): Feedback between groups and asking critical questions.

Week 8: Presentations and reflection on the project

Groups present their Portraits of the River. Peer and teachers’ team feedback.

0 notes

Text

Site-Specific Works

Ana Mendieta

"Cuban-American Ana Mendieta, born in Havana, Cuba, 1948, explores the topic of identity by representing the theme of exile in a temporary yet concrete visual way. Identity can be defined as the permanent characteristics that make someone who they are. However, by depicting only a silhouette of a female body in a changing environment, Mendieta is questioning whether the idea of identity — gender, race, nationality, ethnicity, etc. — is something that is unchanging.[12]

Mendieta studied at the University of Iowa in 1967, where she earned both her BA and MA degrees in painting. At the time, art was becoming more exploratory and experimental, with many artists crossing between multimedia, video art, performance art, installation art, and photography. While studying painting, Mendieta also began to experiment with mixed media and performance, which she is most famous for. Mendieta’s Silueta Series, which stretched from 1973 to 1980, has become her best-known work, crossing boundaries between land art, body art, and performance art. The series of photographs which now comprise the performance work show Mendieta’s silhouette in various landscapes and nature, with her body typically absent from the photographs but occasionally present. Because the Silueta Seriesis created within nature and with the surrounding landscape, it is considered to be earth art. Representing her body or silhouette as part of the landscape, Mendieta creates a crossover between subject and object, meaning her work

points to Mendieta as a subject in so far as Mendieta is a human being who has made the work, but it also points to her as an object in so far as her very silhouette is an object of art also represented by photographic means. Nevertheless, this work of art also problematizes the sharp dichotomy between subject and object, precisely by disclosing a space where it is not clear whether Mendieta is subject or object.[13]

The sites that Mendieta chose for her Silueta Series are temporary and easy to be missed, where “the sense of absence is heightened by the feeling that the wind could make the silhouette disappear. This is a characteristic that can be found in most of the silhouettes, since Mendieta chooses to make her silhouettes in places where their disappearance is only a matter of time”.[14] In other words, Mendieta chooses particular locations in nature where her work will be fleeting and eventually erased by other elements of the environment, making the Silueta Series site-specific. In Mendieta’s Untitled (from the Silueta Series), her silhouette is documented as red flowers on the beach in Mexico, where the water is already removing the flowers and erasing Mendieta’s silhouette. In this silhouette, like many of her silhouettes in the series, Mendieta has portrayed the female silhouette with arms stretched overhead, which “recalls the pose of the goddess with outstretched arms familiar from statues of the Minoan snake goddess amongst many other ancient sculptures and reliefs”.[15] By using the goddess pose, Mendieta reinforces the idea that nature is feminine and depicts a “celebration of feminine power, energy and divinity. Mendieta’s images seem to partake of aspects of all of these meanings, while also retaining something of the opacity of the gesture, its refusal or inability to be rendered directly into speech”.[16]" taken from: https://opening-contemporary-art.press.plymouth.edu/chapter/site-specificity/

"While her work explores the relationship between femininity and nature, Mendieta’s work also has ties to the Santería religion,

which provided familiar connections to memories of her childhood. Santería is the religion of the Yoruba-speaking people of Nigeria who were brought in chains to Cuba. Over time, slaves blended their traditional religion with elements of Spanish Catholicism and European spiritualism. Women are powerful participants and leaders in Santería as over half of the Santería priests are women. Afro-Cuban beliefs like Santería were introduced into New York City during the 1940s and surged in popularity following the exodus from the Cuba after the revolution in 1959.[17]

In many of her works, Mendieta uses blood, which is an essential part of the Santería tradition.

Mendieta’s work also deals with the theme of exile. In 1961, the same year that Fidel Castro declared Cuba a Marxist-socialist country, Mendieta’s parents sent her and her sister to the United States under a program sponsored by the Catholic Church called Operation Peter Pan. Mendieta’s father Ignacio was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 1965 for being involved with planning the Bay of Pigs invasion, and it was also discovered that Ignacio had received training from the FBI and had suspected connections to the CIA. Mendieta and her sister were moved through multiple foster homes in Iowa until being reunited with their mother and younger brother in 1966.[18] It can be seen in the Silueta Series“that having been torn from her homeland is what led her to carry out a dialogue between earth and the female form—and bring to light the ‘space of exile’ or ‘exiled space’ that is disclosed through her art”.[19] By being in exile, one is separated from their home. It seems as though Mendieta tries to portray her lack of home or find a new home in different landscapes, overcoming her exile from Cuba and accepting that the Earth is her home.

Mendieta moved to New York City in 1978 and continued to create her unique earth-body art until her unfortunate death in 1985, where she fell from her apartment window.[20] At the time of her death, Mendieta and her husband, Carl Andre, had only been married for nine months. Andre became a suspect and was “arrested and charged with Ana Mendieta’s death. At the end of the trial, however, the jury dismissed all of the charges against him. Ana’s death has remained a mystery to her family and friends. To many, Andre’s acquittal was not only a sign of a failed justice system, but also of a patriarchal disregard of domestic violence”.[21] Even after her death, Mendieta’s art continues to be relevant to the contemporary world through her discussion of femininity, nature, exile and identity." taken from: https://opening-contemporary-art.press.plymouth.edu/chapter/site-specificity/

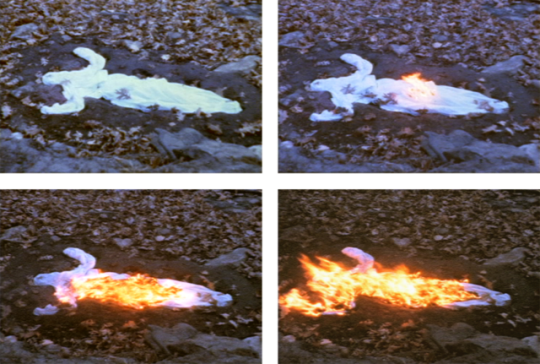

Siluetas (Image from Yagul), 1973

On Giving Life, 1975

Mendieta tends to a study skeleton representative of death, putting modeling clay and red pigment on the bones. After finishing this beautification of the skeleton, Mendieta laid on top of it, creating a physical bond between life and death.

Untitled (Siluetas Series), 1976

Mendieta created this silhouette in the sand then added red pigment. The silhouette deteriorates slowly between each photograph as the waves take away sand, dissolving the outline of the silhouette and washing away all evidence of the artist’s presence.

Untitled (Snow Silueta), 1977

Silueta en Fuego, 1976

Anima (Firework Piece), 1976

The forces that changed Mendieta’s silhouettes were not always drawn out natural regressions. She subjected them in some cases to immediate destruction, using fire or in the case of Anima she created a theatrical display using fireworks.

Tree of Life, 1976

Camouflaged against a tree with her arms raised in a gesture symbolizing a “wandering soul,” the artist is present yet absent. It is only when looking closer at the photograph that the outline of Mendieta’s body becomes visible. Otherwise, she has all but melted into the natural surroundings.

Alma. Silueta en Fuego. Iowa, november 1975

Thomas Hirschhorn

Gramsci Monument

"Gramsci Monument is a new artwork by Thomas Hirschhorn, taking place on the grounds of Forest Houses, a New York City Housing Authority development in the Bronx, New York. Gramsci Monument is the fourth and last in Hirshhorn’s series of “monuments” dedicated to major writers and thinkers, which he initiated in 1999 with Spinoza Monument (Amsterdam, the Netherlands), followed by Deleuze Monument (Avignon, France, 2000) and Bataille Monument (Kassel Germany, 2002).

This fourth monument pays tribute to the Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937), famous for his volume of Prison Notebooks(1926–1937). Gramsci Monument is based on Hirschhorn's will “to establish a definition of monument, to provoke encounters, to create an event, and to think Gramsci today.”

Constructed by residents of Forest Houses, the artwork takes the form of an outdoor structure comprised of numerous pavilions. The pavilions include an exhibition space with historical photographs from the Fondazione Istituto Gramsci in Rome, personal objects that belonged to the philosopher from Casa Museo di Antonio Gramsci in Ghilarza, Italy, and an adjoining library holding 500 books by (and about) Gramsci loaned by the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute in New York. Other pavilions include a stage platform, a workshop area, an Internet corner, a lounge, and the Gramsci Bar—all of which are overseen by local residents.

Gramsci Monument will offer a daily program of lectures by philosopher Marcus Steinweg, a children's workshop run by artist Lex Brown, a radio station, happy hour, and a daily newspaper. Weekly programs include a play titledGramsci Theater, Gramsci Seminars led by international scholars, Poetry Lectures and Workshops led by poets and writers, Art Workshops led by Hirschhorn, open microphone events coordinated by the community, and field trips organized by the project’s “ambassador,” Dia curator, Yasmil Raymond.

Hirschhorn has also created a website as part of the Gramsci Monument. It is a platform offering texts, notes, pictures, and videos documenting the process of the artwork, from its earliest sketches. The website features lives radio streaming, and will be updated daily with documentation from the daily events and philosophy lectures, as well as archived editions of the newspaper." (taken from: DIA: https://diaart.org/exhibition/exhibitions-projects/thomas-hirschhorn-gramsci-monument-project )

"Art in public space[edit]

In 1991, he left graphic design in favor of being an artist.[4] He then started to create works in space that incorporate sculpted forms, words and phrases, free-standing or wall mounted collages, and video sequences.[5] He uses common materials such as cardboard, foil, duct tape, magazines, plywood,[6] and plastic wrap. He describes his choice to use everyday materials in his work as "political" and that he only uses materials that are “universal, economic, inclusive, and don't bear any plus-value”.[7] All of his works are accompanied by written statements that include his observations, motivations and intentions.[8]

Hirschhorn has followed his early commitment to always include the “Other” and address the “non-exclusive audience”[9] in presenting his work in exhibition spaces such as museums and galleries, but also in “public space”: urban settings, sidewalks, vacant lots, and communal grounds of public housing projects.[10]

He has said that he is interested in the “hard core of reality”, without illusions, and has displayed a strong commitment to his work and role as an artist.[11] He described working and production as “necessary”, discounting anyone who encourages him to not work hard, and says “I want to be overgiving in my work”.[11] Hirschhorn is also very adamant about not being a political artist, but creates “art in a political way.”[12]

Aiming "to demonstrate the importance that art can have in transforming life",[13] he created in 2004 the Musée précaire Albinet in Aubervilliers, France, where he presented for two months original artworks from the Musée national d'Art moderne and the Fonds national d'art contemporain. The artworks presented included modern art icons such as Bicycle Wheel by Marcel Duchamp, and works by Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, Salvador Dalí, Josef Beuys, Andy Warhol, Le Corbusier, and Fernand Léger.[14] Located in the public space at the foot of a building bar, in a popular suburb of Paris, the project was an almost unprecedented attempt to bring museum art to underprivileged populations in their own space.[15] The presentation of the works was complemented by numerous workshops, discussions and activities organised with the local population.[16]

Through his experience of working in public space, Hirschhorn has developed his own guidelines of “Presence and Production” in being present and producing on location during the full course of a project in public space.[17] “To be ‘present’ and to ‘produce’ means to make a physical statement, here and now. I believe that only through presence — my presence — and only through production — my production — can my work have an impact in public space or at a public location.”[18] Other ‘Presence and Production’ projects besides the Musée Précaire Albinet include Bataille Monument (Kassel, 2002), The Bijlmer Spinoza Festival (Amsterdam, 2009), Gramsci Monument (New York, 2013), Flamme éternelle (Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2014), What I can learn from you. What you can learn from me (Critical Workshop) (Remai Modern, Saskatoon 2018), and the Robert Walser-Sculpture (Fondation Exposition Suisse de Sculpture, Biel, 2019).

Since early 1990s, Thomas Hirschhorn has created more than seventy works in public space.[19]" (from wikipedia)

"Thomas Hirschhorn was born in 1957 in Bern, Switzerland. Originally trained as a graphic designer, Thomas Hirschhorn shapes public discourse that relates to political discontent, and offers alternative models for thinking and being. Believing that every person has an innate understanding of art, Hirschhorn resists exclusionary and elitist aesthetic criteria—for example, quality—in favor of dynamic principles of energy and coexistence." (from Art21).

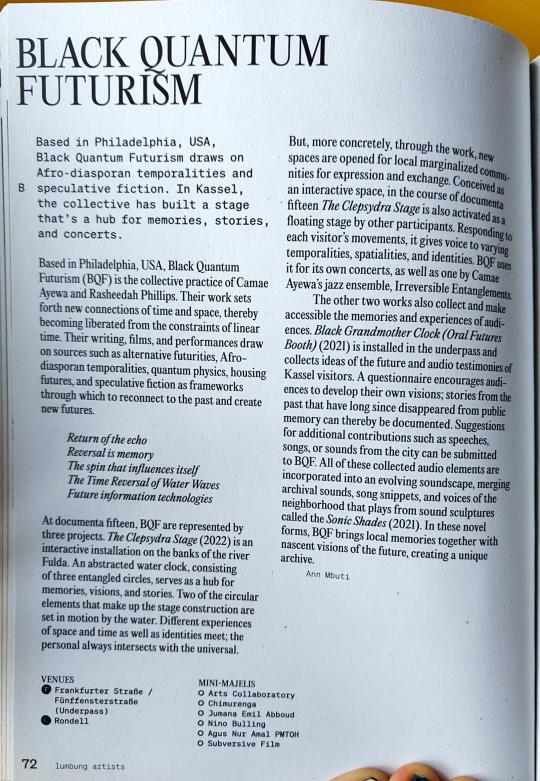

Black Quantum Futurism

Black Quantum Futurism (BQF) is a new approach to living and experiencing reality by way of the manipulation of space-time in order to see into possible futures, and/or collapse space-time into a desired future in order to bring about that future’s reality. This vision and practice derives its facets, tenets, and qualities from quantum physics and Black/African cultural traditions of consciousness, time, and space. Under a BQF intersectional time orientation, the past and future are not cut off from the present - both dimensions have influence over the whole of our lives, who we are and who we become at any particular point in space-time. Through various writing, music, film, visual art, and creative research projects, BQF Collective also explores personal, cultural, familial, and communal cycles of experience, and solutions for transforming negative cycles into positive ones using artistic and wholistic methods of healing. Our work focuses on recovery, collection, and preservation of communal memories, histories, and stories.

Based in Philadelphia, USA, Black Quantum Futurism (BQF) is the collective practice of Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips. Their work sets forth new connections of time and space, thereby becoming liberated from the constraints of linear time. Their writing, films, and performances draw on sources such as alternative futurities, Afro-diasporan temporalities, quantum physics, housing futures, and speculative fiction as frameworks through which to reconnect to the past and create new futures.

Black Quantum Futurism, 2021, photo: Chris Stitch

At documenta fifteen, BQF are represented by three projects. The Clepsydra Stage (2022) is an interactive installation on the banks of the river Fulda. An abstracted water clock, consisting of three entangled circles, serves as a hub for memories, visions, and stories. Two of the circular elements that make up the stage construction are set in motion by the water. Different experiences of space and time as well as identities meet; the personal always intersects with the universal.

More concretely, through the work, new spaces are opened for local marginalized communities for expression and exchange. Conceived as an interactive space, in the course of documenta fifteen The Clepsydra Stage is also activated by other participants. Responding to each visitor’s movements, it gives voice to varying temporalities, spatialities, and identities. BQF uses it for its own concerts, as well as one by Camae Ayewa’s jazz ensemble, Irreversible Entanglements.

The other two works also collect and make accessible the memories and experiences of audiences. Black Grandmother Clock (Oral Futures Booth) (2021) is installed in the Fünffensterstraße / Frankfurter Straße underpass and collects audio testimonies of Kassel visitors. A questionnaire encourages audiences to develop their own visions. Stories from the past that have long since disappeared from public memory can thereby be documented. Suggestions for additional contributions such as speeches, songs, or sounds from the city can be submitted to BQF. All of these collected audio elements are incorporated into an evolving soundscape, merging archival sounds, song snippets, and voices of the neighborhood that plays from sound sculptures called the Sonic Shades (2021). In these novel forms, BQF brings local memories together with nascent visions of the future, creating a unique archive.

BQF has created a number of community-based projects, performances, experimental music projects, installations, workshops, books, short films, and zines, including the award-winning Community Futures Lab and Community Futurisms project. BQF Collective is a 2021 Knight Arts + Tech Fellow; recipient of the 2021 Collide Residency Award, CERN; 2018 Velocity Fund Grantee; 2018 Solitude x ZKM Web Resident; and a 2015 artist-in-residence at West Philadelphia Neighborhood Time Exchange. BQF has presented, exhibited and performed at SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin (2021); Manifesta 13, Marseille (2020); Squeaky Wheel Buffalo (2019); Le Gaite Lyrique, Paris (2018); Serpentine Gallery, London (2017); Philadelphia Museum of Art (2017); MOMA PS1, New York (2017); and Bergen Kunsthall (2017), and among others.

youtube

Watch Night Service was a performance with Irreversible Entanglements and lumbung artist Black Quantum Futurism on the Clepsydra stage floating on the Fulda River, in honor and memory of Juneteenth. Juneteenth (also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day) is a celebration created by formerly enslaved Black people of Galveston, Texas to mark their liberation two years after the Emancipation Proclamation claimed to end slavery. The performance entangled complex and often startling interrelationships of meaning and message between different modes of time, Black histories, and their implications for Black futures through a galvanizing synthesis of speech, sound, and sensation. It took place on the Clepsydra Stage, created by Black Quantum Futurism for documenta fifteen and installed on the Fulda River. “Wading/waiting in the water was an act in the war for liberation that created a temporary time portal, a vortice of protection. To wait in the water, to stop, to rest against the current, to submerge the Master’s clock, is a revolutionary act within a revolutionary act of escape.” – Black Quantum Futurism More about Black Quantum Futurism: https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/lumbu...

"At Documenta 15, BQF present three projects. Along the Fünffensterstraße/Frankfurter Straße underpass, the time-space travel capsule Black Grandmother Clock (Oral Futures Booth) (2021) offers a series of prompts to Kassel locals and visitors and invites them to record their oral stories around communities, housing, and neighbourhoods. The ever-growing soundscape archive brings together local memories with visions of the future, registering undocumented stories for the public memory.

Activated upon standing underneath, the adjacent sound sculpture Temporal Confessional (2021) incorporates three soundscapes that feature interviews between Rasheedah Phillips and CERN physicists merged with sound field recordings of the laboratory’s technological landscapes. The audio installation calls forth all the possible worlds that quantum physics offers beyond the limitations of traditional, linear notions of time. To confront issues of temporality afforded by the prime meridian, Black Quantum Futurism also installed posters in the Fünffensterstrasse from their ongoing research project timezoneprotocols.space, claiming ‘Restore Black Temporal Realities’; ‘We demand temporal reparations. Yesterday, now and tomorrow!’.

Ciudad Abierta (Open City)

The Open City, located on the dunes of Ritoque, north of Valparaíso, arises from the need of its founders and inhabitants to have a space to develop, in the light of Amereida, the project of combining life, work and study from of the encounter between poetry and crafts. The place is an area of 270 hectares located 16km north of Valparaíso. Its land includes an extensive dune field, wetlands with an extraordinary diversity of flora and fauna, a beach border of more than 3 kilometers, ravines and fields.

It was founded in 1970 by poets, architects, designers, sculptors, philosophers and artists largely from the School of Architecture of the Catholic University of Valparaíso, as well as from Latin America and Europe. Its origin is found in the Amereida Journey, a trip made by a group of them in 1965, who, traveling the American continent from Tierra del Fuego to Santa Cruz de la Sierra in Bolivia, questioned themselves about the meaning of America; to then understand and propose, in the poem of Amereida, (the Aeneid of America) a way of living and being American. From the journey and the poem, the Open City is constituted as a landmark or “milestone of America”, which facing the Pacific Ocean, gives rise to poetry in action and by voice, first constructing the public space of the agoras ( place to talk), then the inns (place to live), later the spaces that link (places to visit), and the cemetery.

All this occurs in the creative meeting of life, work and study; unity that becomes possible in the exercise of hospitality, between its citizens and inhabitants, with guests and visitors; until the present. The Amereida Cultural Corporation is today the legal face of the Open City. ( Taken from:https://www.ead.pucv.cl/espacios/ciudad-abierta/ )

Agora of the guests

"The Open City is a Chilean architectural experimentation field, located in the Punta de Piedra sector, in the town of Ritoque, Quintero Commune, Valparaíso Region. History In 1969, the professors and students of the School of Architecture of the Catholic University of Valparaíso formed the Amereida Cooperative. In 1971, the Cooperative purchased an area of land of about 300 hectares,1 north of the Aconcagua River, composed of a dune field, wetlands, ravines, fields and adjacent to the beach for 3 kilometers,2 making up the land where today The Open City is located. Various works of architecture and design are built in this field of experimentation." (...)

"Si bien Amereida no es un proyecto político, poéticamente es altamente revolucionario".5

El poeta chileno Manuel Sanfuentes, miembro de la comunidad, describe así el paisaje y la manera de intervenir en este:

"La mitad de la Ciudad Abierta son dunas. Es un paisaje muy abstracto. Y la duna tiene la gracia de que tus huellas se borran. Vuelves al otro día y la duna está intacta. Ellos nombraron esto como el volver a no saber. El modo de emprender las obras de la Ciudad Abierta pasa siempre por volver a no saber".6Victoria Jolly and Javier Correa, curator of the show La invención de un mar: Amereida 1965-2017 en el Museo de Bellas Artes de Santiago

(taken from wikipedia)

“It is a city, with houses and cemeteries and temples, very special ones, made in the Universidad Católica de Valparaíso. It was really successful and really important for our generation, because in the middle of postmodernism in our school there was a sign that was really important, throughout this really boring architecture: and it was a really good exercise for them. And I think right now it’s not really powerful, but it’s still there in the imaginary, it’s still there working for us in our memory”.

These are the words of Chilean architect Smiljan Radic, in dialogue a few years ago with Hans Ulrich Obrist on the pages of Domus (1020, January 2018) evoking the Ciudad Abierta (Open City), an experience of community and education that to this day remains unique, and above all to this day is still alive and evolving, born in 1971 not far from Valparaíso, surviving the darkness of the dictatorship and the tendency – typical of all Bauhaus-like circles – to crystallise and statically preserve what was once born as a set of revolutionary principles.

How could this happen? The answer lies in the nature of the Ciudad itself, of a community born in Ritoque, not far from Valparaíso, in the rejection of the Beaux-Arts and treatise-style teaching of architecture at the instigation of Professor Alberto Cruz and of poet Godofredo Iommi; an idea of community that abandons Eurocentrism to re-centre its cultural geographies on America, building them on the creation of a poetic journey called Amereida, and that in a totally horizontal and collective dimension brings together students and teachers (role denominations that immediately lose their hierarchical meaning and significance) around the creation of poetic acts that could eventually be translated into architecture.

Poetry is the way to disclose, to understand, the real and the possible, it is something completely open and transient like the sand of the dunes on which the Ciudad Abierta has been welcoming travellers and new members for more than 50 years, in a city visibly lacking a normed and recognisable form; a vision of existence and coexistence that in February 1997 led Domus to choose this experience as a manifesto of social sustainability, a model for the urban communities of the future, to investigate in issue 789, entirely dedicated to the challenge of Designing Sustainability.

Open City, Valparaiso, Chile

The construction of a new town near Valparaiso in Chile has been going on now for over 25 years. To be more precise it is a model of a town, designed and built on the initiative of the School of Architecture at the University of Valparaiso. It is based on the poetic idea of dwelling the threshold, a no-man’s land, and the creative use of existing resources. The aim is to develop an architectural model that can re-define the identity of a South American town and at the same time use space and materials to generate a new form of urban life and community.

(taken from Domus: https://www.domusweb.it/en/from-the-archive/gallery/2022/10/25/ciudad-abierta-building-a-community-from-acts-of-poetry%20.html )

Pope L.

The Whispering Campaign

"William Pope.L, a Chicago-based performance artist known for his interventions in cityscapes, has produced a new work to address the liminal status of refugees and immigrants, specifically for documenta 14. For the first time, documenta, which has taken place every five years in Kassel, Germany since 1955, was also held in a secondary location, Athens, Greece. Pope.L’s VIA-supported project, entitled Whispering Campaign, is a sound installation of whispers emitted through speaker systems, installed both in public spaces and on mobile maintenance trucks, disseminating their content throughout the streets and in restaurants, bars, shopping centers, public transit, and more.

Whispering Campaign first premiered in Athens (April 6) and remained there through July 16, 2017. Simultaneously, the work launched in Kassel on June 10 and remained on display for the respective 100-day duration of documenta 14. Having interviewed migrants in both cities, Pope.L interweaves their stories with local mythology, poetry, and rhythmic, non-narrative elements in his “whispers.” These pre-recorded elements were supplemented by scheduled live performances throughout each 100-day period." (taken from: https://viaartfund.org/grants/pope-l-whispering-campaign/ )

"Pope.L’s contribution took on the guise of an immersive, seemingly omnipresent sound installation titled Whispering Campaign, consisting of thousands of hours of whispered content—addressing nationhood and borders—broadcast throughout Athens and Kassel using both speakers and live “whisperers.” (taken from: https://shop.deappel.nl/products/pope-l-campaign )

Performers spread whispers in the street—adding an unpredictable, living dimension to this wide-spread audio work, which quietly charts a minor history of the city.

The “Whispering Campaign” will run for the 100 days in both Athens and Kassel. Five performers will wander throughout designated areas of the city either broadcasting a pre-recorded score in English, Greek and German or whispering live their observations as they roam the city.

Performances occur Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays in designated areas throughout both cities. In addition to the live performances occurring three days a week, there will be several broadcasts of the pre-recorded text will play at select documenta 14 venues. (taken from: https://www.miandn.com/news/pope-l-in-documenta142 )

b. 1955, Newark, NJ

Lives and works in Chicago, IL

Pope.L is a visual artist and educator whose multidisciplinary practice uses binaries, contraries and preconceived notions embedded within contemporary culture to create art works in various formats, for example, writing, painting, performance, installation, video and sculpture. Building upon his long history of enacting arduous, provocative, absurdist performances and interventions in public spaces, Pope.L applies some of the same social, formal and performative strategies to his interests in language, system, gender, race and community. The goals for his work are several: joy, money and uncertainty— not necessarily in that order. (taken from: https://www.miandn.com/artists/pope-l )

0 notes

Text

Hannah Arendt

i(14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) Germany - USA.

A political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century. In 1998 Walter Laqueur stated "No twentieth-century philosopher and political thinker has at the present time as wide an echo", as philosopher, historian, sociologist and also journalist. Arendt's legacy has been described as a cult.

THE HUMAN CONDITION

The Human Condition, written by Hannah Arendt and originally published in 1958, is a work of political and philosophical nonfiction. Arendt, a German-American philosopher and political theorist, divides the central theme of the book, vita activa, into three distinct functions: labor, work, and action. Her analyses of these three concepts form the philosophical core of the book. The rest of the book is historical in approach.

NOTES:

Vita activa: are 3 fundamental human activities

LABOR

WORK

ACTION

Vita activa is a different to the ultimate way of life of the vita contemplativa - the only truly free way of life.

“The primacy of contemplation over activity rest on the conviction that no human hands can equal in beauty and truth the physical kosmos, which swings in itself in changeless eternity without any interference or assistance from outside, from man or god. This eternity discloses itself to mortal eyes only when all human movements an activities are at perfect rest.

Contemplation was the philosopher’s way of life.

Theoria or “contemplation”, is the word given to the experience of the eternal, as distinguished from all other attitudes, which at most must pertain to immortality.

LABOR: Activity related to biological processes of the body.

-Greeks considered that the labor of our bodies needed by the needs of our bodies (metabolism, survival, food, warmth, etc) was slavish (submissive, passive, servil).

-To labor meant to be enslaved by necessity.

-Labor deals with the tasks that sustain our existence as animals.

WORK: Activity related to the unnaturalness of human existence, -to the world of things- different to the natural surroundings of the environment.

-Artificial.

LABOR OF OUR BODIES IS DIFFERENT TO THE WORK OF OUR HANDS

The work of our hands fabricates the unending variety of things constituting the human artifice (chairs, beds, buildings, cars, etc)

Arendt uses the Latin phrase homo faber (human being the maker) in contrast to labor’s animal laborans. For Arendt, without this distinction, humanity is reduced to animals restricted to the biological processes that merely sustain life (labor) without building a world (work).

ACTION: Activity that happens between people.

-Relation.

-We do not live alone.

-In birth the new comer possesses the capacity to start something anew that is: OF ACTING.

For Arendt, action encompasses both acts or deeds and speech. Like an act, speech reveals the specificity of its agent to others. Action is what makes us human, even more so than work.

THE HUMAN CONDITION OF LABOR IS LIFE ITSELF.

THE HUMAN CONDITION OF WORK IS WORLDLINESS.

THE HUMAN CONDITION OF ACTION IS PLURALITY.

All human conditions are related to politics, yet plurality is the ground of all political life.

All these activities are related to birth and death.

-Labor assures not only individual survival, but the life of the species.

-Work and its products assure and procure the human artifact that transcends life.

-Action engages in founding and preserving political bodies = which leads to remembrance and history.

Hanna Arendt argues: Humans are conditioned beings because everything they come in contact with turns immediately into a condition of their existence.

TERM VITA ACTIVA: a life devoted to public - political matters.

(Politics (from Greek: Πολιτικά, politiká, 'affairs of the cities') is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies politics and government is referred to as political science.) from wikipedia

THE PUBLIC AND THE PRIVATE REALM

Vita activa is rooted in a world of humans.

Things and people form the environment for human’s activities.

World made by humans includes:

-Produced environment.

-Cared for cultivated land

-organization of the city - body politic.

All activities happen in the society of people, of humans; mainly action which can only happen with the company of others.

SOCIAL: alliance of people for a specific purpose

The social has a political meaning.

(Roman word that then became a human condition)

For the greeks, human capacity for political organization stands in direct opposition to natural association whose center is the home and the family.

With the rise of the city-state man received a second life besides his private life, that of the bios politikos - political life-.

Every citizen belongs to two orders: their own and the communal.

Aristotle - of all human activities only two constitute the bios politikos:

SPEECH (Lexis)

ACTION (Praxis)

*from these two activities rise the realm of human affairs. In this realm anything that is necessary (for existence) or useful (for worldliness) is excluded.

-so labor and work are excluded from this realm.

-Thought was secondary to speech but speech and action were equal in importance.

-Through speech one exercises action.

-In the experience of the polis (polis = city-state) everything was decided through words and persuasion, not with force and violence.

-Violence and force were considered pre-political.

Aristotle - everybody outside the polis (slaves and barbarians - family included) was deprived of the way of life in which speech was the main concern for citizens.

to talk to each other, to make decisions together.

-In the polis - in the political realm - nothing was absolute nor uncontested.

While in the household the paterfamilias (father of the household) ruled over the household, over slaves and over the family.

*What was said by the paterfamilias was absolute and could not be contested.

The distinction between the public and the private spheres were then concieved as the political realm and the household.

+The social sphere is neither private nor public, it was born in modern age with the nation-state. Seen as: the collection of families economically organized into the copy of one super-human family is what we call “society” and its political form of organization is called Nation.

+Keep in mind: In ancient Greece whatever was economic or related to the life of the individual and the survival of the species was a NON POLITICAL, it referred to a household affair by definition.

-Historically, the rise of the public realm and the city-state happened at the expense of the private state, the family and the household.

-Households and private lives were not interfered by the polis because without owing a house a man could not participate in the affairs of the world because he would not have a location of his own on the world.

HOUSEHOLD - in it men live together because they are driven by wants and needs.

individual maintenance and survival of the specie needs the company of others.

Men - individual maintenance (nourish)

Women - species survival (birth)

All encompassed by NECESSITY.

While the realm of the polis was FREEDOM

The mastering of the necessities of life in the household was the condition for freedom in the polis.

Politics not only to protect society, but to protect “freedom” or (freedom?) of society.

Protect via (or justify) restraint of political authority.

HOWEVER:

-Freedom only in public realm

-necessity considered pre-political and bound to private households.

-Force and violence are justified in private because they are the only means to master necessity and become free.

Wealth and health= MEN ONLY

-To be pour or ill meant to be subject to physical necessity.

-To be a slave meant to be subject to physical necessity and be subject to man-made violence.

+In the polis (city-state/public realm) there could only be equals. Equals as in peers, men who owned a home and had a family.

+In the household there was the most strict inequality.

To be free meant to:

-not be subject of necessity of life

-not under command of another

-not in command of oneself.

*In the household freedom did not exist

To be FREE meant to be free from the inequality present in rulership and to move in a sphere where ruling or being ruled did not exist.

In the modern world the division of household and public life is blurred with the rise of society. That is, the rise of the household and economic activities to the public realms.

House keeping, the private and the family became collective concerns.

Private interests assumed public significance = SOCIETY

THE RISE OF THE SOCIAL

The emergence of society - the rise of houskeeping, its activities, problems and organizational devices into the public sphere changed the meaning of the public and the private.

Greeks: thought that a life spent in ‘one’s own’ was idiotic

Romans: thought privacy offered a temporary refuge for business (res publica)

Modern Age: Private if the sphere of intimacy.

-In ancient feeling the privative trait of privacy indicated being deprived of something - the highest and most human capacities - RELATION.

A man who lived only only in private life, who like the slave was prohibited to enter the public realm or the barbarian who chose not to establish such a realm were not fully human.

In modern age: social matters are not part of the private realm, because they pertain to the political.

In modern age: the intimate is the opposite to the social.

Explorer and theorist of Intimacy Jean-Jaques Rousseau characteristically rebelled against society’s perversion of the human heart.

Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)

Romanicism: Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate period from 1800 to 1850. Romanticism was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism, clandestine literature, idealization of nature, suspicion of science and industrialization, and glorification of the past with a strong preference for the medieval rather than the classical.[1] It was partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution,[2] the social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment, and the scientific rationalization of nature.(wikipedia)

-The intimacy of the heart has no place in the world.

(I say: one’s body?)

To Rousseau both intimate and social were subjective modes of human existence.

Rebellion of the heart means: individual endless conflicts, inability to be at home in society or live outside of it, ever changing moods, radical subjectivism of emotional life.

Romanticist against society occurred with the discovery of intimacy and it first rebelled against the leveling demands of the social.

Said to be the conformism of society (negative connotation).

these demands were: Its members must act as though they were members of one great family with one opinion and interest.

She mentions: before the concept of equality existed.

Rise of the social = the decline of the family

Arendt -Family was absorbed by corresponding social groups.

*Society excludes the possibility of action - society expects from each of its members a certain kind of behavior by imposing rules which tend to normalize its members.

-Make them behave

-Exclude spontaneous action

-Exclude outstanding achievements.

*conventions are created that frae social status:

RANK in the half-feudal society

CLASS in the 19th Century society

FUNCTION in mass society of the 20th Century.

In mass society the realm of the social embraces and controls all members of the community equally and with equal strength.

Equality in modern world (1950s when the book was written) is: political and legal recognition that society has conquered the public realm and that distinction and difference are private matters of the individual.

In modern age: behavior replaced action as a mode of human relations.

In ancient Greece: Equality meant permitted to live amongst peers, but in the polis it every man distinguishing himself from others with their achievements - showing off.

Public realm was reserved for individuality, to show who they really were.

Due to this reason, they would agree to share the burden of jurisdiction, defense and administration of the public affairs.

Ancient Greeks: they did not find meaningfulness in the everyday but in rare deeds and highlighted achievements and life events.

Arendt - critical to the establishment of behavior over action.

The application of the law in large numbers over politics and history eliminated their very subject matter. Hopeless to search for meaning in politics and history when everything that is not behavior or trend is immaterial.

In regards to the large numbers of a growing society, the Greeks knew their system based on speech and action could only happen in a small city-state scale.

Large numbers of people lead to despotism: either one person rule or a majority rule.

The unfortunate truth about behaviorism is that the more people, the less likely to tolerate non-behavior.

The rise of the social - tendency to grow and devour other realms: the public, the private and the intimate.

Modern age -There was a shift in what was understood as society: “turned all moern communities into laborers and job holders, in other words, they became centered around the once activity necessary to sustain life.

The mutual dependence between people for the sake of life. All activities related to the survival were permitted to appear in the public.

Labor rises to public status

-Labor is a process: it got liberated from the monotonous and circular to a progressive development, a process. This changed the “inhabited” world.

The constantly growing social realm left the public, the intimate and the private relegated.

Constantly growing social realm means that it had an accelerated increase in the productivity of labor.

This growth factor happened due to the organization of laboring and the division of labor.

*Division of labor as in innumerable minute manipulations and development of skills - professionalization

+This could only happen in the realm of the public, because it is there that one can attain excellence. Excellence is assured by being public with others.

+We have become excellent in laboring performance, but our capacity of speech and action lost quality.

-It went to the intimate and the private.

*no activity can become excellent if the world does not provide a proper space for its exercise.

No ingenuity, talent or education can replace the public realm where human excellence can be achieved.

THE PUBLIC REALM: THE COMMON

The term Public means two things:

1st: everything that appears in public can be seen and heard by everybody and has the widest possible publicity.

-Appearance - The something that is being seen and heard by others as well as by ourselves—constitutes reality.

public = Reality.

Reality in the passions of the heart, the toughts of the mind and the delights of the sences have an uncertain existance compared to appearing in public.

To bcome public they are transfored, deprivatizedf and deindividualized to fit public appearance.

examples: in storytelling and art.

But not only: “Each time we talk about things that can be experienced only in privacy or intimacy, we bring them out into a sphere where they will assume a kind of reality they didnt have before.”

The presence of other assure the reality of the world and of ourselves.

While the intimacy of a fully developed private life will intensify and enrich the scale of subjective emotions and feelings, this intensification will always come to pass at the expense of the assurance of the reality of the world and others.

PAIN:

Indeed, the most intense feeling we know of, intense to the point of blotting out all other experiences, namely, the experience of great bodily pain, is at the same time the most private and least communicable of all. Not only is it perhaps the only experience which we are unable to transform into a shape fit for public appear- ance, it actually deprives us of our feeling for reality to such an extent that we can forget it more quickly and easily than anything else. (...) the most radical subjectivity, in which I am no longer "recognizable," to the outer world of life. Pain, in other words, truly a borderline experience be- tween life as "being among men" {inter homines esse) and death, is so subjective and removed from the world of things and men that it cannot assume an appearance at all.

Not everything can appear in the public space, only what is considered to be relevant and worthy of being seen and heard.

Irrelevant becomes a private matter.

HOWEVER: not all private matters are irrelevant. ex. LOVE.

“Love, in distinction from friendship, is killed, or rather extinguished, the moment it is displayed in public.”

Reason: “love can only become false and perverted when it is used for political purposes such as the change or salvation of the world.”

Shift in what is considered to be great: “This enlargement of the private, the enchantment, as it were, of a whole people, does not make it public, does not constitute a public realm, but, it means that the public realm has almost com- pletely receded, so that greatness has given way to charm everywhere; for while the public realm may be great, it cannot be charming precisely because it is unable to harbor the irrelevant.”

2nd the therm public means:

Signifies the world itself, in so far as it is common to all of us and distinguished from our privately owned place in it.

This world is not identical with the earth or with nature. It is related to the human artifact, the fabrication of human hands, as well as to affairs which go on among those who inhabit the man-made world together. The To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it; the world, like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time.

The public realm, as the common world, gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other

In mass society: The world between them has lost its power to gather them together, to relate and to separate them.

Interesting metaphor: “ The weirdness of this situation resembles a spiritualistic seance where a number of people gathered around a table might suddenly, through some magic trick, see the table vanish from their midst, so that two persons sitting opposite each other were no longer separated but also would be entirely unrelated to each other by anything tangible.”

the existence of a public realm and the world's subsequent transformation into a community of things which gathers men together and relates them to each other depends entirely on permanence. If the world is to contain a public space, it cannot be erected for one generation and planned for the living only; it must transcend the life-span of mortal men.

-Without this transcendence into a potential earthly immortality, no politics, strictly speaking, no common world and no public realm, is possible.

-”The common world is what we enter when we are born and what we leave behind when we die. It transcends our life- span into past and future alike; it was there before we came and will outlast our brief sojourn in it. It is what we have in common not only with those who live with us, but also with those who were here before and with those who will come after us.”

-This transcendence of the common world only survives because it appears in public.

-Through many ages before us—but now not any more— men entered the public realm because they wanted something of their own or something they had in common with others to be more permanent than their earthly lives.

*She exemplifies what was done during slavery: not only deprived of freedom and visibility, but also after death there would be no trace that they had existed.

Modern age: loss of authentic concern with immortality and eternity. (Space search?) - regarded as vanity

The philosopher’s vita contemplativa’s main concern was eternity.

Modern age - public admiration and monetary reward.

Public admiration and status are consumed too. They fulfill one’s needs. Public admiration is consumed by ones own vanity.

In Modern age reality does not lie in the public presence of others, but in peoples own needs, needs that can be assured by others but by those who suffer them.

Public admiration and monetary reward are futile (pointless), yet they became more objective and real in modern age.

Money became the fulfillment of all needs.

However, “objectivity” implied before “simultaneous presence of innumerable perspectives and aspects in which the common world presents itself and for which no common measurement or denominator can ever be devised.”

“Only where things can be seen by many in a variety of aspects without chang- ing their identity, so that those who are gathered around them know they see sameness in utter diversity, can worldly reality truly and reliably appear.”

Under the conditions of a common world, reality is guaranteed by the differences of position and the resulting variety of perspectives while everyone is concerned with the same object.

Modern age: men have become entirely private, that is, they have been deprived of seeing and hearing others, of being seen and being heard by them. They are all imprisoned in the subjectivity of their own singular experience, which does not cease to be singular if the same experience is multiplied innumerable times. The end of the common world has come when it is seen only under one aspect and is permitted to present itself in only one perspec- tive.

1 note

·

View note

Text

P3 - Mapping Theory

Read before class and bring questions or segments that they would like to discuss in class:

1 “Cartography as Power” by Jeremy Black until the last paragraph of page 10 of the PDF (page 20 of the article) where it’s marked.

Dual naming - recognition of indigenous names in Australia:

youtube

youtube

youtube

Read in class:

2 “Urban Landscape History-the sense of place and the politics of space” by Dolores Hayden.

Excerpts from Doreen Massey Space, Place and Gender, University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis, 1994:

“The central thread linking the papers is the attempt to formulate concepts of space and place in terms of social relations.”

“Central to that paper is the argument that space must be conceptualized integrally with time; indeed that the aim should be to think always in terms of space-time. That argument emerged out of an earlier insistence on thinking of space, not as some absolute independent dimension, but as constructed out of social relations: that what is at issue is not social phenomena in space but both social phenomena and space as constituted out of social relations, that the spatial is social relations 'stretched out'.”

“The initial impetus to insist on this came from an urge to counter those views of space which understood it as static, as the dimension precisely where nothing 'happened', and as a dimension devoid of effect or implications.”

“There is no holding nature still.' Physics, since the beginning of the century, had been advocating similar views. Thus Minkowski:

The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.3 The view, then, is of space-time as a configuration of social relations within which the specifically spatial may be conceived of as an inherently dynamic simultaneity. Moreover, since social relations are inevitably and everywhere imbued with power and meaning and symbolism, this view of the spatial is as an ever-shifting social geometry of power and signification.