#(it also goes hand-in-hand with the emotional labor women are constantly expected to endure - see: Andy's trauma and loss)

Text

To talk about Twice and villainy is to talk about class and criminality (II)

(Masterlist)

Poverty and crime in Japan

Despite Japan’s perception as a country with relatively low inequality, that reputation has somewhat suffered as capitalism advanced and the country faced economic downturns in the 1990s and 2000s. Japan still claims a high life expectancy, universal healthcare, and low infant mortality, but conversations about wealth have been ongoing: academic Sugimoto Yoshio records the changing discursive landscape that transformed Japan “from a uniquely homogeneous and uniform society to one of domestic diversity, class differentiation and other multidimensional forms.” Sugimoto describes the increasing discussion of a kakusa shakai, a disparity society, and the emergence of a karyu shakai—the underclass. Since Sugimoto’s article was published in 2010, [source] many issues of this kakusa shakai identified by him and academics from ten-plus years ago have persisted, such as the proliferation of non-regular workers (now comprising 15% of the labor force), [source] the growing wealth inequality being reflected in Japan’s aging population, and the increasing numbers of elderly poor. More recently, increasing attention has been devoted to the issue of child poverty, usually connected to the low incomes of single, working-class mothers. [source] In 2017, Japan’s relative rate of poverty rose to 16.3% (for comparison, the relative rate of poverty in the U.S. declined to 17.3%), and many non-regular workers expressed fears of getting sick and losing their jobs, remarking on their total lack of stability. [source] [source]

Reflecting working-class desperations worldwide, the most common crime in Japan throughout the Heisei era (1989-2019) was theft. Theft, particularly of material goods, should be thought of as a crime of need, arising out of a lack of a particular good and the money to pay for it. It’s a crime that points to a society with unmet needs, and an effort to criminalize those who try to have their needs met through their own power when social institutions refuse to help. It has long been asserted that the “concepts of "crime" are not eternal,” and that “the very nature of crime is social, and is defined by time and by place and by those who have the power to make the definitions.” The contested legality of abortion is a simple illustration of how definitions of “crime” are constantly in flux, constantly debated, and not at all intuitive or self-explanatory. Being able to label an action, a behavior, or a group of people “criminal” or “illegal” is an act of power, and people doing the labeling have a vested interest in determining what “crime” is. Activist Sabina Virgo, source of the previous quotes, elaborates: “The power to define is [...] the power of propaganda. [...] Most of us accept the images and definitions that we have been taught as true, neutral, self-evident, and for always; so the power [...] to define what is right and wrong, what is lawful and what is criminal, is really the power to win the battle for our minds. And to win it without ever having to fight it.” [source]

The choice to inscribe theft as a crime, as an act to be punished, is part of that propaganda. It’s the decision to criminalize poverty and to protect profit over people, rather than rightfully interpreting theft as a symptom of a dysfunctional system. In Japan, this looks like a large percentage of crimes getting committed by the elderly, particularly theft (90% of shoplifting offenders were elderly women), and a large percentage of incarcerated seniors, who by 2018 made up 12% of the prison population; on the other hand, the law is just beginning to address unethical workplace practices like overwork and power harassment, while facing a rising number of reports on domestic and sexual violence—the raw numbers of which are likely even higher than reported. [source] The difference between which acts are ruled criminal, and who gets criminalized for acting, lays stark the difference between the unethical actions undertaken by the powerful, and the criminalized actions undertaken by the powerless; the more an unethical act abides by and benefits entrenched systems of power, the more we are compelled to see it as normal and acceptable, whereas actions, however minuscule, that resist the hegemony of the capitalist class and reject its propaganda end overwhelmingly with more debt and prison time.

Family and class.

The socioeconomic forces that shift our societies are no less felt within the family structure, and family may be one of the first social units to see destabilization. In a world of increasing economic strife, it isn’t uncommon for parents to spend more hours working than at home, or even to travel abroad to provide for their family in their native country, to see traditional norms rewritten as children either move away or continue to live with their parents, as marriage and birth rates rise or fall, and as the elderly are either embraced back into the family structure or left to fend for themselves. Due to generational wealth, family is also often the determining factor for whether or not someone succeeds, to what degree, and with how much effort. Needless to say, when it comes to “class,” the topic of family receives much scrutiny as academics, journalists, and creators delve into the ways our notions of “family” shift according to time, class, and economics.

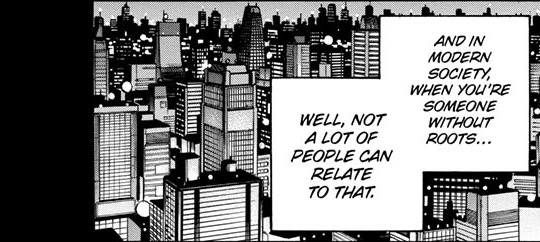

Consider that in Japan, and de facto in most countries in the world, the first and most important safety net in modern society is the family. “Public social protection schemes are based on the assumption that everyone is supported by family first,” [source] and this includes the assumption of financial assistance, and duties like procuring care for the family’s elderly. The Japanese family registry—the koseki—is a family tree that records births, deaths, and marriages, and is in many ways a codification of the centrality of family, bloodline, and inheritance. [source] When a character like Jin says that he’s “someone without roots,” perhaps our first impulse is to imagine it as a description of emotional relationships, a difficulty he experiences because others can’t relate to him, but it’s not purely an intangible feeling; there are very tangible repercussions to being “unrooted.” Without a stable family, “unrooted” people miss the safety net that family is supposed to be—they miss its protection. Under a system that expects the worst scourges of modernity to be alleviated by the family, this leaves the “unrooted” out in the cold.

These failures on the part of the traditional family structure to account for prosperity, whether it be through generational poverty, through abuse, or through instability and absence, often leads to a restructuring of these bonds. In Japan, “when the economic bubble burst and the recession exposed the illusion of permanent and stable employment for the diligent workforce, the children found that attaining a better living than their parents through hard work and better education was no longer guaranteed,” and once economic success was no longer guaranteed through traditional paths, children’s bonds “shifted to more individualized, voluntary ties.” [source] Of course, shifting economic conditions aren’t the only reason for non-blood-related individuals to come together—many also come from backgrounds of loss or rejection. As a columnist wrote: “Tragedy and suffering have pushed people together in a way that goes deeper than just a convenient living arrangement. They become, as the anthropologists say, “fictive kin.””

BNHA poignantly embodies these dynamics as Jin tearfully declares that the LOV gave him a “place to belong.” In Japanese, the term used is 居場所 (ibasho), a phrasing which contains the 居 kanji for “residing” or “residence,” as well as “to exist” (it reprises in “I was happy to be (居られて) here” in Jin’s final thoughts). A literal reading could render ibasho as a “place to reside,” or a “place to exist”—something offered only by the friends Jin made, who are a sanctuary from the public that overlooked his alienation, rendering him invisible and denying him existence. For their parts, the other villains are also marked by an ambiguous relationship to their biological family, if not an absence altogether. Himiko and Tomura, whose backstories were touched upon in the same arc, led contentious family lives: Himiko’s parents appeared to regularly condemn their child, and the repeated rebukes that Tomura (Tenko) endured from his father—including an incident of physical assault—resulted in the awakening of Decay and the deaths of his family.

These three were remnants of broken traditional families, scattered and largely isolated across the country. Originally united as a villain group bound loosely by similar goals, they eventually came to rely on each other for survival once the stability of All For One’s hideout and resources were stripped away, leaving them to face a hostile world saturated by incessant policing and villain power struggles. Mutual protection became not only necessary for survival, but necessary for triumph—the League of Villains are consistently shown to be at their best when working as a team, operating on a mixture of communication and even blind trust. Ironically, it’s only when they try to bring outsiders into the fold that the situation goes awry, suggesting that their strength isn’t in numbers or recruitment, but in the relationships they’ve built between one another, relationships that ultimately coalesced under the unpopular worldview that maybe there is nothing wrong with them, but something very wrong with the world. What the readers come to understand is that the LOV are no longer only convenient allies: they can best be understood as a residence for a group of outcasted people with similar experiences and outlooks, who finally found in each other the shelter that traditional family had failed to provide.

77 notes

·

View notes