#Ann Ting Gock

Text

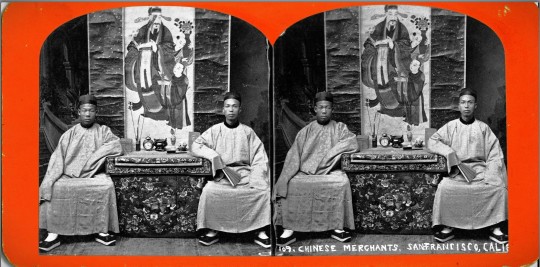

“109. Chinese Merchants, San Francisco, Calif.” c. 1890 – 1899? Stereograph by Nesemann Woods Gallery, Marysville CA (from the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection of the University of British Columbia Library).

Merchants of Old Chinatown

In the late 1840s and the 1850s, Chinese merchants and traders made their initial foray into California. By February 1849, the number of Chinese had increased to 54 and by January 1850, historians would count 787 men and two women in San Francisco. In December 1849, the Alta California newspaper reported that 300 Chinese convened a meeting at the Canton Restaurant on Jackson Street for the purpose of organizing the “Chinese residents of San Francisco” and engaging the services of lawyer Selim E. Woodsworth to “act in the capacity and adviser for them.”

In his book, Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown, historian John Tchen wrote about the vanguard of old San Francisco Chinatown’s merchant elite as follows:

“These pioneers hailed primarily from the Sanyi (Saam Yap) or Three Districts [三邑], as well as the Zhongshan area in the immediate vicinity of Canton. It's important to note that Nanhai (Namhoi) and Panyu (Punyu) stood out as the most prosperous districts within Guangdong Province. Their economic pursuits ran the gamut from cultivating fertile agricultural lands, breeding silkworms and fish, to crafting silk textiles, producing ceramics for both domestic and international markets, and engaging in various other commercial endeavors.

“What set apart the merchants and artisans from Sanyi and Zhongshan was their mastery of a more refined city dialect compared to their Siyi (Sei Yap) counterparts, who mainly consisted of poorer, rural communities. Remarkably, over 80 percent of Chinese immigrants in North America originated from the Siyi [四邑] region. A noteworthy portion of these Sanyi merchants belonged to the emerging class of compradores, individuals who facilitated business transactions on behalf of Western trading companies. These California-based Sanyi merchants thus brought prior experience in dealings with Western entrepreneurs, and California was seen as a promising arena to expand these lucrative connections.”

With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May of 1869, the more sophisticated and adventurous members of San Francisco’s pioneer Chinese merchant community would begin exploring other cities in the United States in search of opportunity.

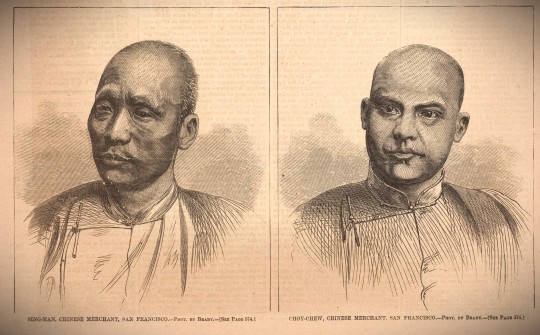

“Sing-Man, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco” and “Choy-Chew, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco,” Harper’s Weekly, September 4, 1869, wood engraving on paper. Artist unknown, artist after a photograph by Mathew Brady, 1869 (from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery).

For example, in the Harper’s Weekly article (Sept 4, 1869, page 574), the reporter identified merchant Choy Chew as a San Franciscan and a talented linguist of sufficient intellect and stature to be invited to give a speech at a European-American banquet. He reportedly visited Chicago with a fellow merchant, Sing Man, before traveling to New York where the pair were regarded as “representatives of Chinese industry and commerce.”

At the banquet in Chicago, Choy Chew delivered the following remarks:

”Eleven years ago I came from my home to seek my fortune in your great Republic. I landed on the golden shore of California, utterly ignorant of your language, unknown to any of your people, a stranger to your customs and laws, and in the minds of some an intruder — one of that race whose presence is deemed a positive injury to the public prosperity. But gentlemen, I found both kindness and justice. I found that above the prejudice that had been formed against us, that the hand of friendship was extended to the people of every nation, and that even Chinamen must live, be happy, successful and respected in ‘free America.’ I gathered knowledge in your public schools; I learned to speak as you do; and, gentlemen, I rejoice that it is so; that I have been able to cross this vast continent without the aid of an interpreter; that here in the heart of the United States I can speak to you in your own familiar speech, and tell you how much, how very much, I appreciate your hospitality; how grateful I feel for the privileges and advantages I have enjoyed in your glorious country; and how earnestly I hope that your example of enterprise, energy, vitality, and national generosity may be seen and understood, as I see and understand it, by our Government …

”We trust our visit, gentlemen, may be productive of good results to all of us; that the two great countries, East and West, China and America, may be found forever together in friendship, and that a Chinaman in America, or an American in China, may find like protection and like consideration in their search for happiness and wealth.“

-- from the Scientific American, new series, vol. 21, no. 9, p. 131 (August 28, 1869)

The founding in 1888 of the Merchants’ Exchange in old San Francisco Chinatown represented the logical culmination of several decades of robust business operations by the pioneer Chinese merchants in the city and beyond.

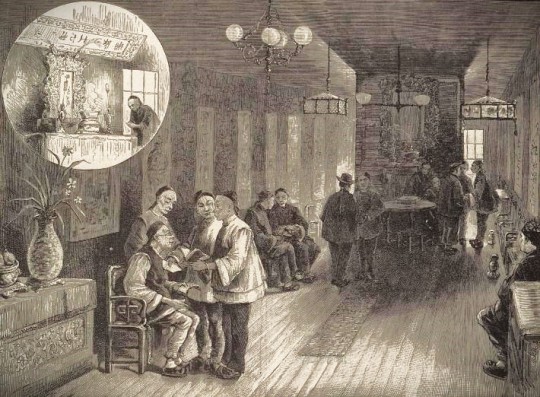

“Chinese Merchants’ Exchange, San Francisco.” Lithograph from Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 26, March 18, 1882 (from the collection of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In his book, A Guide Book to San Francisco (published by The Bancroft Company in 1888), John S. Hittell described the Chinese Merchants Exchange as follows:

“At 739 Sacramento Street are the new rooms of the Chinese Merchants' Exchange. They are fitted up in the ordinary Chinese style, and though presenting no special attraction to the visitor, the business transacted there is of considerable importance. A Chinese merchant, contractor, or speculator never starts on any enterprise alone. He always has at least one partner, and in most cases several. He makes no secret of his transactions, but converses about them at the exchange, and often goes there in search of capital when his own means are insufficient. He sometimes applies to that institution to find him a capable man to manage a new business which he is about to start. If, as often happens, one be selected who is in debt to other members, they make arrangements which will not interfere with the new enterprise; and the debtor is not unfrequently released from his obligations.”

Fung Tang

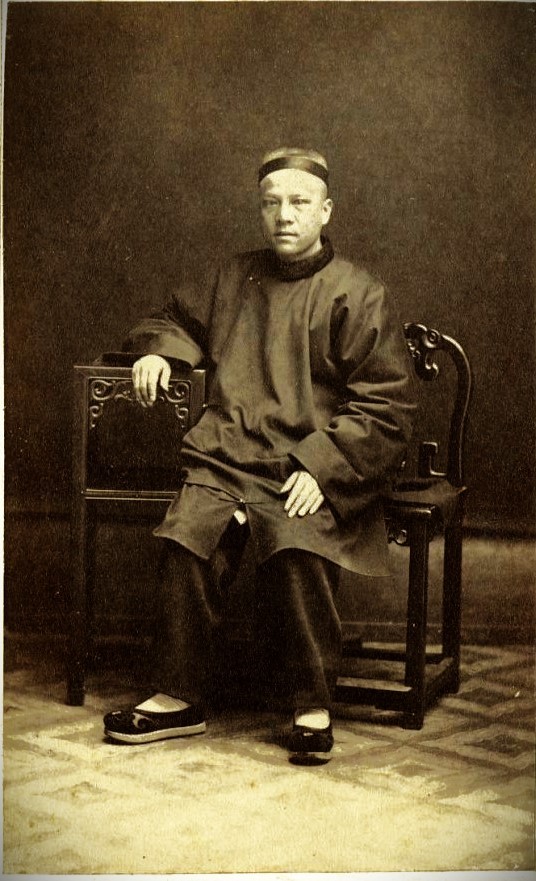

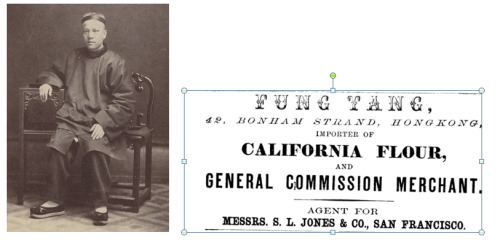

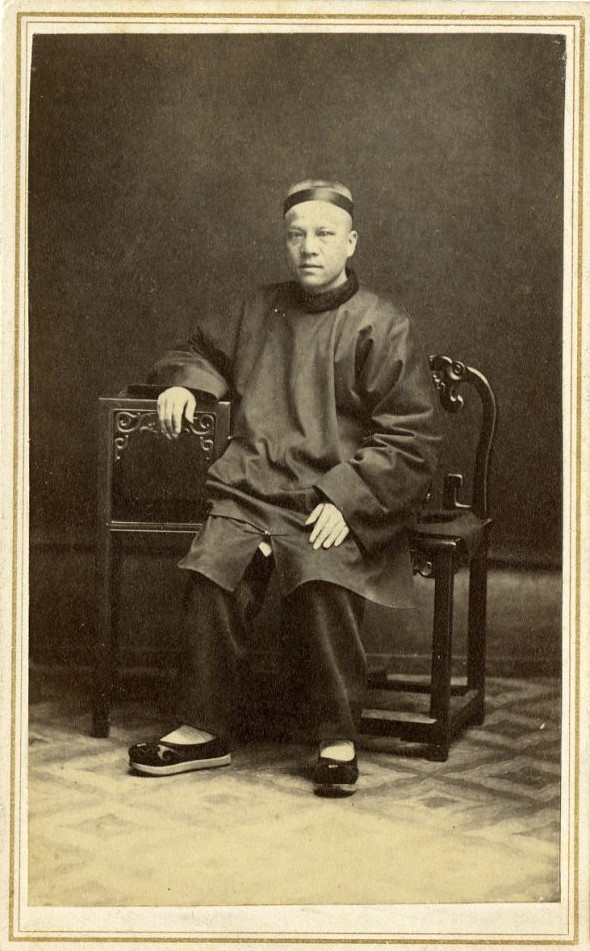

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

The address of the Merchants’ Exchange at 739 Sacramento Street was hardly surprising, as it shared the same building which had housed the mercantile house of a legendary merchant, Fung Tang. Historian York Lo, in his article for The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website, described Fung as “a native of Jiujiang (Kow Kong) in the Nanhai county (南海九江) in Guangdong, Fung Tang followed his uncle Fung Yuen-sau (馮元秀) to California in 1857 at the age of 17 and worked at Tuck Chong & Co (德祥號辦莊), a trading business founded by his uncle and his fellow Nanhai native Kwan Chak-yuen (關澤元).” In the Langley San Francisco directory of 1868, the Tuck Chong & Co. is listed as “(Chinese) merchants” located on Chinatown’s first main street at 739 Sacramento Street.

“In his spare time,” York Lo writes, “he learned English from Reverend William Speer and became fluent in the language. With his linguistic skills, he became a bridge between the Chinese and the white community in San Francisco and even befriended Peter Burnett, the first Governor of California, who described Fung in his memoir as ’a cultivated man, well read in the history of the world, spoke four or five different languages fluently including English, and was a most agreeable gentleman, of easy and pleasing manners’.”

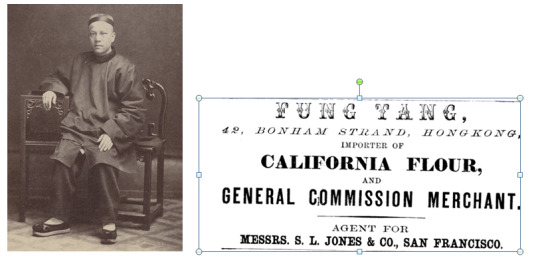

As such, Fung Tang must be considered as a logical client for the pioneer Chinatown photographer, Kai Suck. A professional studio portrait would have conferred respectability in the eyes of the non-Chinese businessmen and politicians with whom he interacted. In fact, Fung appears to have deployed the same portrait now reposing in the collection of the California Historical Society as part of his commercial advertising in Hong Kong.

An advertisement for Fung Tang’s flour import business in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong.

For more details about Fung’s business exploits and his public service, including his election to the board of directors of the Tung Wah clinic (the original predecessor organization of the future Chinese Hospital), readers are encouraged to read York Lo’s piece here: https://industrialhistoryhk.org/fung-tang-the-firm-the-family-the-transpacific-metals-trade-and-tin-refinery/?fbclid=IwAR3DU6pEcaEw6w2uH1OZvFBFL8vg-Rl4keBS-VkbcttFuHKlx973g3ZjcY8

Tchen asserts that the influx of British and other Western imperialist powers into China’s major treaty ports transformed the status of merchants engaged with Western trading companies. Rather than operating on the margins of Qing-era society, the merchants gained unprecedented prestige and influence. Beyond China's borders, they experienced far more freedom to engage in trade and amass substantial profits without the worry of state-imposed restrictions. They rapidly acquired the necessary language skills and business acumen to navigate their newfound opportunities.

San Francisco’s early Chinese merchants swiftly grasped the English language and American business practices, excelling in American-style transactions, and developing strategies for fostering positive relations with the general San Francisco populace. The local press affectionately labeled them "China Boys." They made conscious efforts to participate in the celebrations of significant American holidays, further endearing themselves to the San Francisco community.

This approach significantly bolstered their rapport with the local population, as evidenced by the California Courier's glowing praise: “We have never seen a finer-looking body of men collected together in San Francisco. In fact, this portion of our population is a pattern for sobriety, order, and obedience to laws, not only to other foreign residents, but to Americans themselves," declared Cornelius B. S. Gibbs, a marine-insurance adjuster, in 1877. Gibbs emphasized the high esteem in which Chinese merchants were held among white business circles. “As men of business, I consider that the Chinese merchants are fully equal to our merchants. As men of integrity, I have never met a more honorable, high-minded, correct, and truthful set of men than the Chinese merchants of our city.”

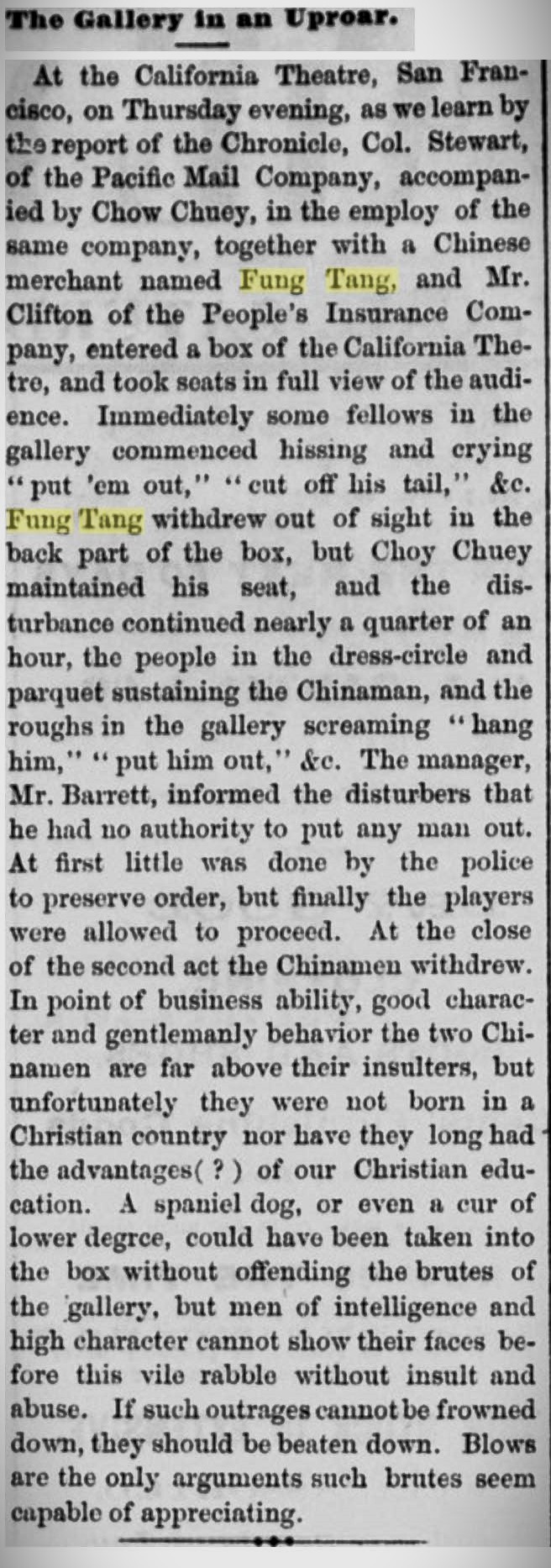

Attempts to participate in mainstream society, however, were not always welcomed by lower-class elements of white society as evident in this news account about Fung Tang’s appearance in San Francisco’s California Theatre in September 1869:

Clipping from the San Jose Mercury News, September 18, 1869 (vol. I no. 42)

Fung Tang’s transpacific success in San Francisco was hardly unique among the ranks of Chinatown’s early merchant class. He exemplified the business acumen of his fellow pioneering entrepreneurs and their establishment of transpacific trading posts in strategic locations.

Lai Chun-chuen and Chy Lung Co.

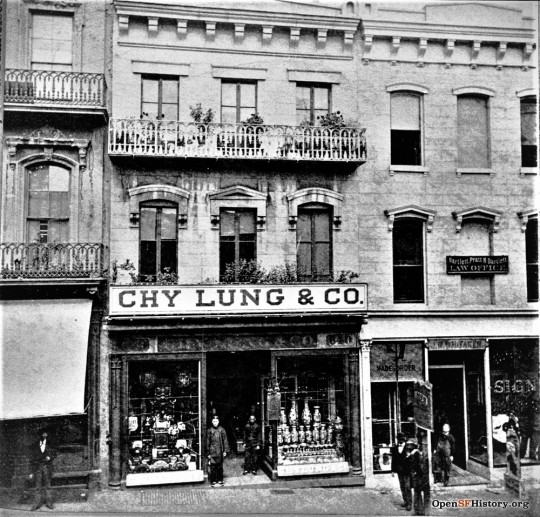

The story of the pioneer business of Chy Lung & Co. predates the history of San Francisco Chinatown itself, and its establishment spurred the rise of Chinatown’s first commercial strip, Sacramento Street (唐人街; canto: “Tohng Yahn Gaai”) or “Chinese Street.”

An enlargement of the stereograph taken by Carleton Watkins for the Thomas Houseworth & Co., and “[e]ntered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866 by Lawrence & Houseworth, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the Northern District of California.”

“Among the early Chinese settlers were merchants like Lai Chu[sic]-chuen,” the late historian Judy Yung wrote in her pictorial book, San Francisco’s Chinatown (published by the Chinese Historical Society of America). “Upon arrival in 1850, he opened Chinatown’s first Bazaar at 640 Sacramento Street, importing teas, opium, silk, lacquered goods, and Chinese groceries.”

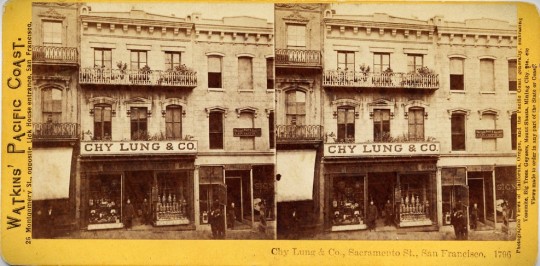

"Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento St., San Francisco. 1796" c. 1866. Photograph by Carleton Watkins for his Watkins' Pacific Coast stereograph series (from a private collection).

Chy Lung’s founder, Lai Chun-chuen (a.k.a. Chung Lock), came to San Francisco in 1850 from Nam Hoi county. According to UC professor Yong Chen, the business founded by Lai and, his partners Xie Mingli, Fang Ren, Sheng Wen, and Chen Nu, appear in the earliest business directories for San Francisco. A “Chyling, china mer, 188 Washington” appears in the Parker directory for 1852-1853. The Colville’s directory of 1856 lists a “Chy Lung (Chinese) mcht, Canton Silk and Shawl Store, 166 Wash’n,” and the business would remain on Washington Street (moving to 612 Washington St. by 1858) until 1863 when it relocated to 642 Sacramento Street. By 1865, the Chy Lung & Co. had either expanded or taken over the address of 640 Sacramento Street.

Portion of the stereograph “No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co.,” c. 1866. Published by Lawrence & Houseworth (from in the collections of the Society of California Pioneers, Wells Fargo Corporate Archives, and the Library of Congress).

“He imported Chinese prefabricated houses and cargoes of Chinese goods, teas, silk, lacquer and Porcelain wears, and even opium,” historian Phil Choy wrote. “The drug that made American merchants millionaires in the China trade now found its way to California for both the Chinese and American markets Chy Lung was one of only two Chinese businesses at the time that advertised in an American newspaper, the Daily Alta California.”

“No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento Street.” c. 1866. Published by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from in the collection of the New York Public Library).

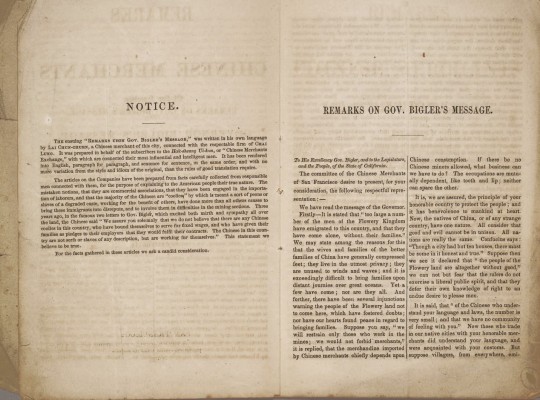

Lai Chun-chuen is remembered not only for his business acumen but also as the principal author of the objections to the anti-Chinese movement in California and plea for civil rights as published in the pamphlet, Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco, upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections (San Francisco: Whitton, Towne, 1855).

The preface to Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections of 1855 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The second line of the first paragraph identifies Lai Chun-chuen as “a Chinese merchant of this city, connected with the respectable firm of CHAI LUNG.”

Chy Lung & Co. continued to play a leading role in the Chinese merchants exchange until Lai Chun-chuen’s death on August 30, 1868. The business remained a fixture of the Chinatown business community for the rest of the 19th century, and it adopted the new communications technology of the telephone, as shown by the Pacific Telephone directory for the Chinese Exchange in 1902.

The listing for Chy Lung & Co. as it appeared in the Wells Fargo directories of Chinese business for 1878 and 1882.

The Chy Lung & Co. business, and others established by Chinatown's merchants, soon comprised a source of both tangible and symbolic power within the rapidly growing Chinese community in the American West. As the Chinese immigrant population swelled, businesses catering to their specific needs diversified and expanded. A hierarchical structure emerged, influenced by both economic factors and the district of origin. The wealthier Sanyi individuals typically presided over larger, commercially successful enterprises, including import-export firms. Those from the Nanhai District dominated the men's clothing and tailoring sector, as well as butcher shops. The neighboring Shunde District populace exercised control over overalls and workers' clothing factories.

“S.F. Chinatown 1898 C12”. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Collection of the San Francisco Public Library). A well-attired merchant and possibly his son walk south on Spofford Alley from Washington to Clay Street.

Meanwhile, Chinese hailing from the Zhongshan District, which represented the second-largest Chinese population in California, were prominent in the fish and fruit orchard businesses, as well as in the production of women's garments, shirts, and underwear.

"Quan Quick Wah"

“Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). A descendant of the large, confident man shown in traditional robes identifies him as San Francisco merchant “Quan Quick Wah.” Based on other photographs of this Chinatown location, the pair appears to be walking on the west side of Waverly Place toward its intersection with Clay Street. In his book about Genthe’s Chinatown photographs, historian Jack Tchen wrote about this imposing figure followed by a bodyguard as follows: “The powerfully built man dressed in traditional silk robes has been described as a tong leader. Whether he was a tong leader, a wealthy merchant, or both, his dress and carriage convey a strong presence. Tong leaders came to rival the power of wealthy merchants. The man following the merchant or tong leader is said to have been his bodyguard, protecting him from the attack of a rival tong. In the photograph the two are passing under ornate cloth lanterns that indicate a pawnshop business.”

"Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). This full photograph in the Library of Congress shows that Genthe’s image fortunately included a portion of the sign for the entrance to a basement restaurant. The signage (which appears in other photographs of this area), indicates that the merchant and bodyguard were photographed walking on the west side of Waverly Place (at about no. 23 and 25 Waverly) and toward the southwest corner of its intersection with Clay Street. Tchen’s guess that the background store frontage was a pawnshop is probably correct, as the “Qung Hing Art Co.” pawnshop occupied space at 25 Waverly during the 1890s. The headquarters of the merchant-controlled, Ning Yung district association was located at 23 Waverly.

Yee Ah-Tye

In old Chinatown, merchants’ personal use of bodyguards or alliances with fighting tongs were common. The organization and fragmentation of district and clan associations, along with sharp business competition, often placed lives, as well as livelihoods, at risk. For example, the Kong Chow association traced its origin to about 1853, when the influential community leader, Yee Ahtye (a.k.a. “George Athei”) persuaded members of his Yee clan of Sunning, which had remained in the Sze Yup Co. (after a number of clans split off to organize today’s dominant Ning Yung Association), to finally secede. The action by the Yee clan was joined by clans from Hoiping and Enping counties after a dispute over the presidency of the Sze Yup Co. in 1862. The resulting new association, the Hop Wo, soon challenged the merchant Ah-Tye for the custody of a piece of land on which Ah-Tye had allowed the Sze Yup Association to build a headquarters building. Yee eventually deeded the land to a new Kong Chow Association, which his fellow Sunwui merchants founded in 1866. The dispute over this property raised to such a level that Yee and his associates were compelled to organize a secret society, the Suey Sing Tong, to protect the asset and enforce his decision.

Portrait of Yee Ah-Tye (courtesy of the Chinese Six Companies). Yee was an elite merchant of Chinatown and was considered a co-founder of the Suey Sing Tong.

Born around 1829 in Guangdong province, Yee Ah-Tye had arrived in San Francisco just before the gold rush at around 20 years old. In spite of his humble beginnings, Yee had learned English in Hong Kong and swiftly ascended to a position of authority within the influential Sze Yup [pinyin: "Siyi"] Association. The Sze Yup Association, along with similar Chinese district associations, played a crucial role in assisting newly arrived Chinese immigrants during the 19th century. The organizations provided accommodation and job opportunities.

Aside from his many business accomplishments, Yee famously cross paths with the legendary, San Francisco madam Ah Toy. The conflict arose when Ah Toy accused Yee of demanding a tax from her prostitutes on Dupont Street. Despite her origins in China, Ah Toy had by then lived in America for three years and become familiar with its legal system. She boldly threatened to take legal action against him, a move she would not have dared to undertake in China.

The August 1852 report in the Daily Alta California newspaper highlighted Ah Toy's shrewdness, emphasizing her knowledge of living in America and her ability to navigate the legal system. She resided close to the police station, fully aware of where to seek protection, having faced legal proceedings herself numerous times. The reporter gleefully suggested that Yee use caution about overstepping his authority, warning that he might lose his dignity and end up in custody.

A year later, Yee faced legal trouble himself, being arrested for assault and grand larceny. The San Francisco Herald alleged Yee “inflicted severe corporeal punishment upon many of his more humble countrymen … cutting off their ears, flogging them and keeping them chained for hours together.”

After moving to Sacramento in 1854, Yee also relocated his business activities in 1860 to La Porte, California, where hydraulic and drift mining operations for gold occurred. Yee acquired a partnership in a store called Hop Sing & Company which supplied merchandise and Chinese contract laborers. By 1866, it was the richest Chinese store in that town, with a value of $1,500 (about $36,000 in 2005 dollars).

According to one of his descendants, Lani Ah Tye Farkas, the pioneer Yee Ah Tye reportedly lived thirty-four years in La Porte as a successful merchant, running the Hop Sing and Company store and representing the Chinese community in the area. He had three wives and four children, three of whom were girls. Unlike most other Chinese fathers at the time, he invested in the education of his daughters – he even bought a piano for his youngest daughter, Bessie, who became an accomplished pianist. As a leader in the Hop Sing Association, he founded a small hospital to serve the elderly Chinese men of La Porte.

“The temple ruins at San Francisco's Lincoln Municipal Park Golf Course was once part of the Lone Mountain Cemetery, a gift of Ah Tye,” Lani Ah Tye Farkas wrote in 2000. “Other glimpses of his life in America can be seen in deeds, mining claims, tax assessments, newspaper articles, and land that he once owned. Yee Ah Tye's legacy, however, is in his descendants. Many Chinese with common last names like Chan, Lee, and Wong may have no relationship with one another. However, the descendants of Yee Ah Tye have borne his unique last name through six generations, in the words of the Yee family genealogy, ‘spreading like melon vines, increasing continuously’” Yee died in 1896. (see: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/pc289j76z)

Contract Labor

At the lower end of the business hierarchy, the Siyi or Four District residents comprised the largest and least affluent group of Chinese immigrants. They typically occupied occupations such as laundries, small retail shops, and restaurants and the bulk of the laborers in the contract labor system.

In the period preceding the Civil War, there was a concerted effort by certain individuals to introduce contract laborers into the United States. A letter penned by C. V. Gillespie to Thomas Larkin on March 6, 1848, sheds light on this initiative. Gillespie expressed a keen interest in the idea of bringing Chinese emigrants to the country, suggesting that a variety of skilled workers and laborers could be sourced:

"One of my favorite subjects or projects is to introduce Chinese emigrants into this country,… Any number of mechanics, agriculturists and servants can be obtained. They would be willing to sell their services for a certain period to pay their passage across the Pacific…."

The practice of importing contract laborers to the United States began in the late 1840s and continued through the 1850s. However, enforcing labor contracts proved to be a challenging endeavor on American soil. A case in point involved an Englishman who, upon bringing fifteen Chinese laborers to the country bound by a two-year contract, found that they immediately reneged on their agreement upon arrival. Authorities, at the time, were reluctant to intervene in such disputes.

In 1852, Senator George B. Tingley introduced a bill in the California State legislature aimed at legalizing and facilitating the enforcement of contracts allowing Chinese laborers to sell their services to employers for periods of up to ten years at fixed wages. This proposal, however, faced significant public backlash and was ultimately defeated after a heated debate. The subsequent year saw members of Chinese companies admitting that they had initially imported workers during the early years of the Gold Rush. Yet, due to unprofitability and difficulties in enforcing labor contracts, they abandoned this practice.

“San Francisco Chinese Merchant” no date. Photographer unknown, possibly by Ann Ting Gock (from a private collection). This rare and unusual image suggests that the individual might not have been a mere merchant at all, but a member of the Chinese consular staff. He is seen wearing his 清代官帽 (canto: "ching dai gwun moe") or official's headwear. The Qing official headwear or Qingdai guanmao (Chinese: 清代官帽; pinyin: qīngdài guānmào; lit. 'Qing dynasty official hat'), also referred to as the “Mandarin hat” in English, is a generic term which refers to the types of guanmao (Chinese: 官帽; pinyin: guānmào; lit. 'official hat'), a headgear, worn by the officials of the Qing dynasty in China. The merchant is attired in a "changshan" or "changpao" or long robe. The robe worn in the photo was derived from the Qing dynasty-period "qizhuang" (the traditional dress of the Manchu people). Changshan were, and are, traditionally worn for formal pictures, weddings, and other formal Chinese events.

Credit-ticket System

Beyond the initial years, it became widely acknowledged that Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States voluntarily, free from any servile contracts or duress. Many emigrants either financed their own passage or received assistance from relatives and friends already residing in California. The prevailing method for the majority of Chinese immigrants during the 19th century was the credit-ticket system. Under this system, an emigrant would receive financial support for their passage in a Chinese port. Upon reaching their destination, the emigrant was expected to repay this debt using their future earnings. It is important to note that this system differed from the contract labor arrangement, where laborers were bound to serve for a specified duration.

The precise origins of the credit-ticket system remain uncertain. However, merchant brokers in Hong Kong were established to provide advanced passage funds, approximately forty dollars, to the emigrants. Corresponding entities in the United States were responsible for collecting these debts and aiding the newly arrived immigrants in finding employment.

Two merchants with pipes. No date, photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The stores and offices that the merchants of Chinatown had opened starting in the mid-19th century became the basis of real and symbolic power in the growing regional community of Chinese living in the American West. That power, including the ability to mobilize for social change within the narrow role afforded Chinese in the society, manifested itself in the family and district associations headed by local merchants.

“The merchant class has traditionally been the one sector of Chinese society able to foster unity and bring about social change,” wrote historian Thomas W. Chinn about the role of the merchant class in San Francisco Chinatown (and beyond). “The merchant-directors of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association must be well-established businessmen in the local community as well as outstanding members of their own family associations. They have already played a leading role in their own social circles before becoming merchant-directors, and they enjoy a great deal of respect. . . Thus the friendly corner grocer may simultaneously be the president of his family association and his district association as well as a merchant-director.”

Lew Kan

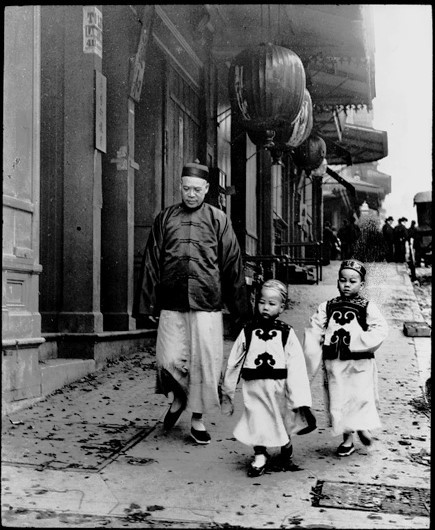

“Children of High Class” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Merchant Lew Kan (a.k.a. Lee Kan) walking with his two sons, Lew Bing You (center) and Lew Bing Yuen (right). According to historian Jack Tchen, “Lew Kan was a labor manager of Chinese working in the Alaskan canneries. He also operated a store called Fook On Lung at 714 Sacramento Street between Kearney [sic] and Dupont. Mr. Lew was known for his great height, being over six feet tall, and his great wealth. The boys are wearing very formal clothing made of satin with a black velvet overlay. The double mushroom designs on the boys’ tunics are symbolic of the scepter of Buddha and long life.” The photograph appears to have found the trio walking down the south side of Sacramento Street below Dupont Street.

By the time photographer Arnold Genthe had photographed merchant Lew Kan and his two sons on Sacramento Street (as well as two other earlier photos of their four sisters in Portsmouth Square), Lew had already attained legendary status as one of Chinatown’s leading merchants. Born in 1851, Lew entered the US in 1866.

Author Roland Hui (in his biography of pioneer Chinese American industrialist Lew Hing), wrote about Lew Kan and his dry goods business called Lun Sing & Co. at 706 Sacramento Street as follows:

“He started Lun Sing, one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, around 1867, a year after he immigrated to the U.S. In 1896, the business gained notoriety by harboring a young Chinese revolutionary named Sun Yat-sen during his first visit to the continental United States. Sun advocated overthrowing the Qing monarchy and establishing a Chinese republic. His ideas were too radical for the politically uninitiated Chinese community. Kang Youwei, the architect of the ill-fated “Hundred Day Reform” in China in 1898, favored establishing a constitutional monarchy around Emperor Guangxu. Forced into exile after the power-hungry Empress Dowager crushed his reform, Kang launched the Chinese Empire Reform Association, also known as Baohuanghui (Save the Emperor Society), the following year in Victoria, Canada. Baohuanghui quickly gained widespread support among overseas Chinese since the idea of having an emperor at the top of the social order who ruled with the Mandate of Heaven had been ingrained in the Chinese psyche for thousands of years. The San Francisco Baohuanghui chapter was founded in 1899 at 146 Waverly Place. Lew Kan supported Kang’s political agenda despite having met Sun several years earlier, and in 1901 became the president of the San Francisco chapter of Baohuanghui. Many scholars observed that Baohuanghui was the first organization that evoked the patriotic sentiments of overseas Chinese. And when Liang Qichao, Kang's most famous student, stopped over in San Francisco during his 1903 America tour, thousands of Chinese flocked to listen to his speeches. As the man who organized these community-wide activities, Lew Kan's stature and influence in San Francisco Chinatown must have been substantial. In addition, he was one of the wealthiest Chinese merchants, reportedly owning several general merchandise stores with an estimated net worth of $2 million. That was an astronomical sum in those days. In addition, he was a director of the Kong Chow Company, a district association representing Xinhui."

Decline of Merchant Influence

The organizational expression of Chinatown’s merchant elite, the Chinese Six Companies, wielded considerable authority within San Francisco and beyond. The Six Companies and its constituent district associations comprised the quasi-government of Chinese America, offering social services, mediating disputes, and representing the community's interests to external forces. With the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882, their grip on power began to weaken.

Portrait of a merchant with fan and scroll. No date, photograph possibly by Shew’s studio (based on the detail of the end-table), from the collection of the Stanford Libraries.

The decline of the Six Companies’ influence can be attributed to various reasons. One significant factor was their inability to adapt swiftly to the evolving socio-economic landscape within Chinatown. As the community faced new challenges, including the punitive extension of Chinese exclusion with the Geary Act of 1892, the Six Companies struggled to effectively navigate these changes, leading to a loss of faith among the populace in their ability to address emerging issues.

The Geary Act of 1892 extended and strengthened the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, requiring most Chinese Americans – native and foreign-born -- to carry an internal passport in the form of certificates of identity or face arrest and deportation. It intensified discriminatory measures against the Chinese community, fostering widespread discontent and resistance.

In response, the Six Companies initiated a national boycott against the Geary Act. The boycott aimed to unify Chinese immigrants and their supporters across the United States, urging them to refuse compliance with the law as a form of protest. It gained substantial momentum, with significant participation from Chinese communities in various cities, voicing opposition to the Act's discriminatory provisions.

The board of directors of the Chinese Six Companies, no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Based on the screen panels in the background (which remain in the Six Companies’ meeting hall at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco), the photo appears to have been taken after 1906.

Despite its initial vigor, several factors led to the ultimate collapse of the national boycott against the Geary Act. First, the federal government intensified its efforts to enforce the Geary Act. Authorities conducted widespread raids and inspections, threatening deportation and imposing harsh penalties on those failing to comply. The fear of reprisals and the potential disruption to livelihoods coerced many Chinese immigrants into reluctantly acquiescing to the Act's demands.

Second, the broader American society exhibited little sympathy or support for the Chinese community’s plight. The prevailing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country and the lack of significant political backing from other institutions diminished the effectiveness of the boycott. Without widespread solidarity, the Chinese American community struggled to sustain its resistance.

Finally, the decision by the US Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893), dealt a major legal setback to Geary Act resistance and undermined the credibility of the Six Companies. The decision validated the Geary Act and created an environment of fear within the Chinese American community. The inability to overturn the Geary Act by legal means diminished trust in the Six Companies’ capacity to protect the community's interests.

Photograph of a merchant from Chinese Business Partnership Case File for Quong Lee Company, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from the files of the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office). The immigration investigative case file indicates that the individual in this photo was certified as a business partner and a "merchant" who was “able to travel to and from the U.S. as a ‘Chinese subject of exempt class’ under the ‘Chinese Exclusion Acts’ (1882-1943).” The Quong Lee & Co. (a.k.a. Quong Lee, Quong Lee Sing) operated what business directories from 1875 to 1905 variously described as a “tailor,” “general merchandise,” “clothing,” and “dry goods” business continuously at 828 Dupont Street. By the time this merchant sat for his photo in 1896, the national boycott led by Chinese merchant organizations against the Geary Act of 1892 had collapsed, and studio portraits such as this became an essential pieces of evidence to support applications for the coveted merchant exemption from the extended Exclusion Act.

This heightened sense of vulnerability played into the hands of tongs, which, capitalized on the weakened merchant community. Amidst the faltering influence of the Six Companies, tongs emerged as influential entities that would come to dominate Chinatown’s socio-political structure and shape mainstream society’s perceptions of the Chinese community for the next three decades.

“High-binders Retreat” no date. Photograph by Goldsmith Brothers (from the Cooper Chow Collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). Tong members at ease in front of their fraternal order's headquarters.

Tongs, in contrast to the Six Companies' diplomatic approach, adopted a more assertive stance in responding to discrimination and persecution faced by the Chinese community. Their readiness to protect their members (which also included merchants), and defy external pressures resonated with many disillusioned residents.

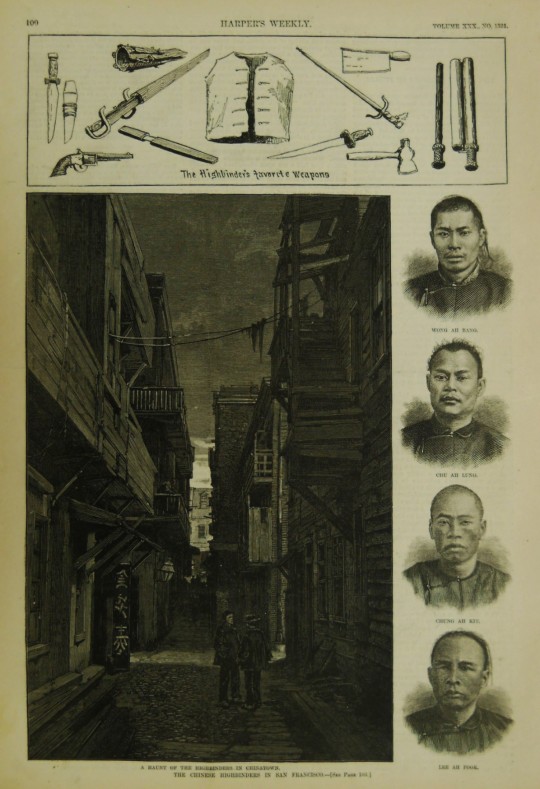

“A Haunt of the Highbinders in Chinatown.” Harpers Weekly, February 13, 1886 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

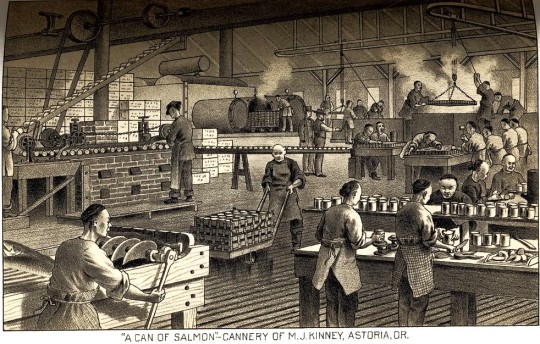

Moreover, the tongs during this period had begun to diversify their activities beyond traditional, illicitl sources of income such as prostitution, gambling, and drug distribution. Tongs began engaging in both legitimate businesses, including labor contracting for the Alaskan canneries. This diversification allowed them to accumulate resources, expanding their sphere of influence within Chinatown and beyond as alternative community governance structures, while still reserving often violent means to protect their interests.

Chinese salmon cannery works in Astoria, Oregon, c. mid-1880s. Drawing from West Shore, June 1887, from the Special Collections, University of Washington). The early 20th century would be marked by violent struggles between tongs such as the Suey Sing and Bing Kung for control over the labor contracting business for the canneries.

The ascendancy of tongs at the turn of the century coincided with the republican movement in China. Historian Phil Choy wrote that the Chee Kung Tong, the original triad society, had been evolving in response to revolutionary movements in mainland China:

“Chee Kung Tong returned to its lofty political ideologies in 1900 when both Kang Yu-wei’s Reform Party and Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Party sought its assistance. Originally the Chee Kung Tong supported Kang Yu-wei, but as Dr. Sun’s ideology gained popularity, the Chee Kung Tong, switched allegiance. When in 1904 immigration officials did not allow entry to Sun, the leader of the Chee Kung Tong, Wong Sam Ark, and the Tong’s attorney Oliver Stidger, along with Reverend Ng Poon Chew and Reverend Soo Hoo Nam Art, worked successfully for his release. Sun stayed at the Chee Kung Tong headquarters and used the society’s newspaper, the Chinese Free Press, to propagandize his revolutionary cause. Accompanied by Wong Sam Ark, Dr. Sun went on a nationwide tour to generate support and contributions.”

The tongs’ economic power and their active involvement in fundraising for the republican movement not only showcased their financial strength but also demonstrated their ability to wield influence as an overlapping and sometimes counter-force with the merchant elite. This dual role as (1) economic powerhouse within the local community, and (2) significant contributor to a revolutionary cause overseas underscored their influence. The growth of that influence came at the expense of the merchant elite in shaping both local and international affairs.

Merchants, however, would continue to exert influence through clan organizations, tongs, business associations, Nationalist Party of China chapters, and Chinese “consolidated benevolent associations” in San Francisco Chinatown and communities across North America through the exclusion era, war, and peace.

The meeting hall of the Chinese Six Companies, c. 1920 (by then incorporated as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco. Photographer unknown (from the Jese B. Cook collection of the Bancroft Library).

Chinatown's merchant community would face new challenges to their capacity as civic leaders when the political center of gravity across US Chinatowns would shift again in the last quarter of the 20th century.

[updated 2023-12-28]

#Chinatown merchants#Sing Man#Choy Chew#Chinese Merchants Exchange#Fung Tang#Lai Chun-chuen#Chy Lung & Co.#Yee Ah-Tye#Chinese Six Companies#Kai Suck#Ann Ting Gock#Lew Kan#Chee Kung Tong#Quong Lee & Co.

0 notes

Photo

William Shew’s Pioneer Gallery, young woman with fan, after 1880, albumen cabinet cards, California Historical Society

When A Nascent National Security State Spurred Early Chinese American Studio Portraiture

In her book, In Sight of America: Photography and the Development of US Immigration Policy, historian Anna Pegler Gordon, observes that the introduction of “photographic identity documentation” in 1917 spurred the Chinese community and the relatively new Immigration Bureau to turn to Chinese photographers for identity certificates, as well as family use. Newcomers and deportees were photographed for federal authorities, and “a number” of professional photographers operated in the Chinatown of pre-1906 San Francisco.

Ka Chau reportedly established San Francisco’s first known Chinese “Daguerran Establishment” in 1854. Pegler-Gordon’s research found at least 25 professional Chinese photographers and galleries in San Francisco and other localities. The demand was sufficiently robust to induce white photographers to advertise in Chinese language newspapers for clients.

“I count nearly a dozen photographers who operated before the turn of the

century, most in the carte de visite and cabinet card trade,” Anthony Lee writes in his book Picturing Chinatown Art and Orientalism in San Francisco. “They include Ka Chau on Sacramento Street in the 1850s; Kai Suck at 929 Dupont Street in the late 1860s; Ah Soo, War Tong Ho, and Ah Hing (at unknown addresses) in the early 1870s; Ah Chew at 492 Montgomery Street in the early 1870s; Lai Yong at 743 Washington Street between 1869 and 1881 and then incorporated as Sing Sung and Company at the same 743 Washington Street studio between 1882 and 1883; Ming Hin Chio and Sim Chung (at unknown addresses) in the early 1880s; and Wai Cheu Hin at 800 Stockton Street in the early 1890s. There may indeed have been many more Chinese photographers—those who did not advertise or who worked under the auspices of others . . .”

The Chinese consul general employed Fong Get Photo Studio (at 914 Stockton St.) to take official portraits that would bear inscriptions to federal officials, including the local immigration commissioner; Chinatown’s merchant elite retained non-Chinese studios, such as Hamilton’s Gallery and Shew’s Pioneer Gallery, to take their photos and, presumably, enhance their community standing; and the Immigration Bureau contracted with the studios to photograph detainees.

William Shew

Brilliant samples of the portraiture by William Shew’s studio may be viewed at the California Historical Society’s webpage here: https://californiahistoricalsociety.org/blog/from-the-archives-chinese-likenesses-from-san-francisco-portrait-studios/)

“Chay Yune” by Shew’s Pioneer Gallery c. post-1880 (from the collection of the California Historical Society

William Shew’s Pioneer Gallery, young woman with fan, c.1880, albumen cabinet cards, from the collection of the California Historical Society.

William Shew; Untitled self-portrait with a group of Chinese, c. 1882 (from the private collection of Stephen White). According to White, “Shew worked with the abolitionist movement in Boston, and then became involved in social issues in San Francisco. This photograph may have been a response to the Chinese Exclusion Act signed into law by President Chester Arthur in 1882, eliminating Chinese citizenship as well as immigration for ten years.”

Kai Suck

Little is known about Kai Suck whose photographic gallery was located at 929 Dupont Street in old Chinatown.

“Hand Gim” c. 1867. Photograph by Kai Suck. This portrait of a young man indicates that the photography studios were patronized by Chinese of different classes and not merely by the merchant elite.

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

In his day, Fung Tang was one of the elite merchants doing business in early Chinatown and San Francisco. As historian York Lo has written for The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website, Fung was “a native of Jiujiang (Kow Kong) in the Nanhai county (南海九江) in Guangdong, Fung Tang followed his uncle Fung Yuen-sau (馮元秀) to California in 1857 at the age of 17 and worked at Tuck Chong & Co (德祥號辦莊), a trading business founded by his uncle and his fellow Nanhai native Kwan Chak-yuen (關澤元).” In the Langley San Francisco directory of 1868, the Tuck Chong & Co. is indeed listed as “(Chinese) merchants” located on Chinatown’s first main street at 739 Sacramento Street.

“In his spare time,” York Lo writes, “he learned English from Reverend William Speer and became fluent in the language. With his linguistic skills, he became a bridge between the Chinese and the white community in San Francisco and even befriended Peter Burnett, the first Governor of California, who described Fung in his memoir as ’a cultivated man, well read in the history of the world, spoke four or five different languages fluently including English, and was a most agreeable gentleman, of easy and pleasing manners’.”

As such, Fung Tang must be considered as a logical client for the photography provided by Kai Suck’s studio. A professional portrait would have conferred respectability in the eyes of the non-Chinese businessmen and politicians with whom he interacted. Moreover, the photo would have elevated his standing from the mass of laborers in the Chinese community and, ultimately, in the eyes of Immigration Bureau officials with whom he would have undoubtedly dealt during his transpacific travels after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.

For more details about Fung’s business exploits and his public service (including his election to the Tung Wah clinic, the original organization of the future Chinese Hospital), readers are encourage to read York Lo’s piece here: https://industrialhistoryhk.org/fung-tang-the-firm-the-family-the-transpacific-metals-trade-and-tin-refinery/?fbclid=IwAR3DU6pEcaEw6w2uH1OZvFBFL8vg-Rl4keBS-VkbcttFuHKlx973g3ZjcY8

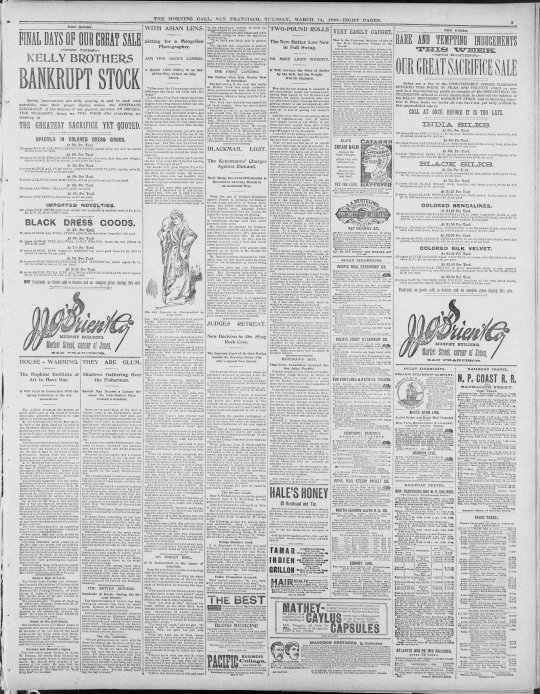

Ann Ting Gock

Against this background comes an announcement by Stanford Libraries that the university has acquired two images of “Ah Gum” and “Ah Gum’s cousin” by photographer Ann Ting Gock. Little appears to have been written about Gock and his 842 Clay Street studio, aside from a feature article in The Morning Call newspaper (which is replicated below). By 1900, and according to the telephone directory, Gock had moved his photography studio to 721 Dupont (a few doors north of the Hang Far Low restaurant).

According to the dealer, Scott Brown, from whom Stanford acquired the images, the albumen prints were mounted as cabinet cards with his stamps on the verso (back), and they bear handwritten captions in ink by “an unidentified Christian visitor to Chinatown.”

“Ah Gum & Child” -- December 6, 1893. Photograph by Ann Ting Gock (from the collection of the Stanford Libraries).

As Brown describes, “[t]his image shows a young Chinese woman wearing a dark silk tunic and trousers. Between her knees stands a nicely dressed, three or four year-old girl dressed in typical Chinese attire.”

The caption on the verso of the “Ah Gum & Child” image reads “Mrs. Hull, Chinese Mission teacher M. E. Home, took me to call at two Chinese homes (or rooms) & this is the picture of the mother & child of one. San Francisco, Dec. 6-93." The author of this note is not identified.

The ‘Mrs. Hull” to which the caption refers was Ida Hull, a thirty-five-year-old widow who taught at the Methodist Episcopal Church's Chinese Mission in San Francisco, beginning in 1891. Hull spent most of her life in close association with Methodist women’s work in Chinatown. Her first task as a teacher was to start an “infant school” (kindergarten), which grew rapidly, and she was also in charge of home visitations. In the latter role she quickly became a Methodist leader in the rescue of abused women and girls – and famous for kicking down doors. For example, in an 1897 Call article, Ida Hull is the first missionary the author seeks out as she reports on “the bravest women in the world.” Hull is quoted in the article as saying, “‘I don’t use much tact—tact isn’t useful among the Chinese. A hatchet is more effective. . . . Oh, I only use it to break down doors with,’ she laughed, ‘not on their heads, although sometimes if I were a man I should like to.’”

According to Brown, “Ah Gum, the name of the sitter for this portrait, is a common transliteration of names for both Chinese men and women of the era. However, she may be the Ah Gum referred to in the Report of the Chinese Mission to the California Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church (San Francisco: Cubery and Co., 1890): ‘Five Christian girls married during the year, including Ah Gum, who was for many years the ward of Grace Church Sunday School.’"

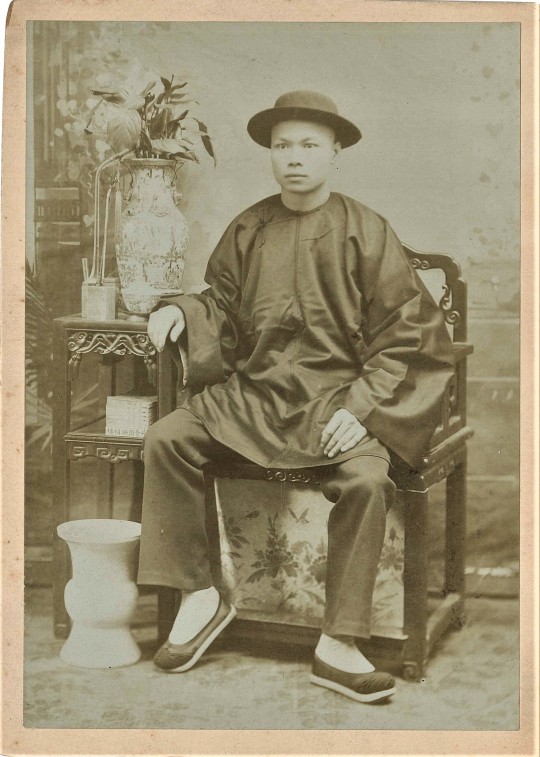

“Ah Gum's Cousin” -- December 6, 1893. Photograph by Ann Ting Gock (from the collection of the Stanford Libraries).

“The images nominally conform to standard American studio portraiture of the late 19th century, but with distinctive Chinese elements,” Brown observes. “Here we have the patterned carpet, the Chinese table and chair, a vase with foliage, and even the spittoon, here a white urn at the feet of the sitter.”

Aside from the photographer's stamp (in the form of his red-inked chop) on the back of the mount, two other stamps were affixed to the verson, i.e., the business name of “ANN TING GOCK / 842 Clay Street / San Francisco, Cal.,” and a template for a negative No. ___ and the short tag-line: “Copies of this picture can be had at any time at reduced rates.”

The name of Ah Gum’s cousin remains unknown to this day, but the handwritten caption on the verso of the mount imparts vital information for that era of Exclusion, i.e., “born in America.”

Students of US constitutional law will recall that the US Supreme Court’s landmark decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898) would not be decided for another five years. In the second decade of an even more punitive Exclusion Act, the issue of whether “a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicil [sic] and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China,” remained in doubt.

Thus, “Ah Gum’s Cousin” would not have known for another several years whether he had automatically become a U.S. citizen at his birth. Nevertheless, Ah Gum believed it important enough for her youngish-appearing cousin to sit for his portrait in support of his claim and whatever rights – aspirational or otherwise – that flowed from the fact of his American birth.

As for the Ann Ting Gock, few examples of his work, and that of other 19th century Chinese American photographers, survive.

Fortunately for the community’s historians, The Morning Call newspaper published a substantial feature story about its reporters’ visit to Gock’s studio in March of 1893 (“With Asian Lens: Sitting for a Mongolian Photographer”), which I have transcribed as follows:

THE MORNING CALL, SAN FRANCISCO, TUESDAY, MARCH 14, 1893

WITH ASIAN LENS.

Sitting for a Mongolian Photographer.

ANN TING GOCK'S CAMERA.

A Quaint Little Gallery in an Out-of-the-Way Corner on Clay Street.

“Allee same like Chinawoman; allee same like Japan one dollar half; full length.”

It was Ann Ting Gock, explaining to two CALL reporters the poses and prices contingent upon being exposed before the sensitive plate of an Asian camera.

A Chinese photographer forsooth is Ann Ting Gock, a bright intelligent Asiatic, and a rate-cutter on all the galleries in the city.

To reach his den you go up a little winding stairway that leads off Clay street, near Stockton, until you reach a little landing-place.

If you look straight ahead you will probably find Ann Ting Gock at the top of the next flight nursing a cute little yellow baby all done up In gorgeous red and yellow and green rags. And Mrs. Ann Ting Gock may also be on the top landing with another and younger infant, Ann, as she was when THE CALL representatives visited the place the other day.

Ann Ting Gock will motion you to go into the tiny room to the left of the first lauding and say, “I be right down."

He speaks very good English for a Celestial, and will tell you that he has been in this State for twenty years. He wears a royal Nile green robe, has beautiful long and clean finger nails and treats his patrons with an Imperial condescension and genuine politenees. [sic]

This is the main office and showroom. There is a showcase in it and the proprietor's bed. The bed is open, the blankets and sheets turned back. It looks rather out of place in a photographer's reception parlor, but it also looks clean and inviting— that is if one cares to sleep on that kind of bed. Two gray blankets over hard, smooth boards. That is the softness thereof.

There is an old faded carpet on the floor, and it might be swept cleaner. In the showcase are various card photographs, panels, cabinets, and all sizes of Chinese men and women.

Back of the showroom and communicating with It by a narrow door is the family kitchen and washroom, all in one and all of It not more than 8 feet square.

Well, THE CALL reporters, one of whom was a young lady, decided that the Japanese costume was best suited to her peculiar style of beauty.

Then Ann Ting Gock led the way across the landing to the operating-room. This is not a large apartment, but long enough for focusing with a Chinese camera. A skylight admits ample white light, and the dressing-room to the left, though little bigger than a good-sized packing-box, is larger than Chinese ladies usually enjoy when at home.

Much Chinese furniture, imitation of ebony chairs and tables, tea cups, Chinese gowns and swords and armor and bric-a-brac of all sorts are in rather promiscuous profusion in the operating-room.

“Some men like to be soldiers, some rich merchants, some actors, and some all kinds,” explained Ann, which meant that his Oriental patrons have a fondness for appearing in their photographs tike any-thing but what they are; a fondness by the way. that in some very rare cases has been known to extend to the more enlightened Caucasian race.

When THE CALL’s lady reporter had emerged from the dressing-room, gorgeous in a fur-trimmed, many-hued Japanese gown, the courteous Ann robbed his bonds admiringly and predicted a “velly” good picture.

Now the lens In Ann's camera is not quite up to the modern makes found In the more fashionable galleries, but it prints the image on the sensitive plate as large and as life-like as the best of them.

THE CALL man was permitted to peep through the ground glass in the back of the camera after the proper focusing had been done.

Then he beheld, what everybody who focuses a camera beholds, the subject standing on her bead, with her skirts, however, clinging decorously to her heels.

A passing word ought to be said of Ann’s rather antiquated camera, it is an odd-looking piece of furniture, judged by the modern makes, and as Ann says came all the way from China. It rests on three heavy legs, and is raised or lowered by putting in or pulling out wooden pegs in a long stick attached to the bottom of the camera.

Ann Ting Gock is his own operator, he differs from the white artists in his line by leaving the question of the pose or attitude entirely to the victim’s lack of judgment or good taste, as the case may be.

There are no torturesome posing-irons or headrests in Ann’s operating-room, and the time of exposure, with bright sun outside, is not quite a second.

When the exposure was duly made Ann hastened into his 2x2 dark room, and the negative was duly developed.

He came out in a few moments with the glass negative in hand and exhibited it to his patrons.

The figure was a little dim and the lines seemed to lack sharpness, but two days later, when the print was made, quite a presentable likeness was shown.

The negative lead been duly retouched, though not perhaps with the most artistic skill in the world, and the flesh was soft mid smooth, if a trifle hazy.

It was worth the money paid, at any rate, besides it is not every day that one poses before an Asiatic artist on this side of the water.

LUKE NORTH.

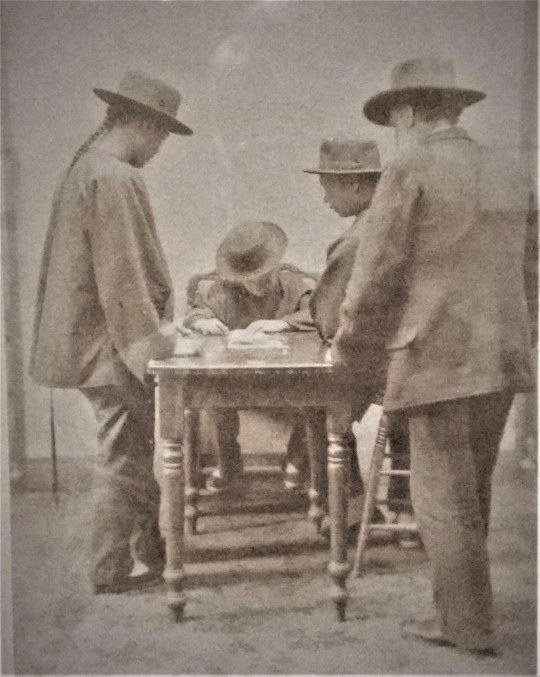

“The Fan Game,” photograph by Ann Ting Gock (from the collection of the California Historical Society). The scene of three players hovering over the dealer’s table raises the question whether the photograph was a candid shot or posed in Gock’s studio.

Lai Yong

Born in China in 1840. Lai Yong has the distinction of being the earliest known Chinese artist who was active in California. He maintained a gallery in San Francisco on Dupont Street (now Grant Avenue) from 1867-75. His painting of Adolph Sutro in the California Historical Society is the only one extant. Exh: Mechanics' Inst. (SF), 1869. [Source: Edan Hughes, "Artists in California, 1786-1940"]

Lai Yong advertised in the 1868 Langley directory as a “(Chinese) portrait painter” located at 659 Clay Street. The same directory in 1881 disclosed that Lai Yong’s “photograph gallery” still operated at 743 Washington St.

Lai Yong’s studio portraits of Chinese gentlemen “evidence similar accessories and attitudes seen in those from the Kai Suck studio,” according to Asian American Art: A History, 1850-1970.

Two Young Performers In Costume, c. 1872. Photograph by Lai Yong (from the collection of the California Historical Society.

For the California Historical Society’s summer 2022 exhibition, “Chinese Pioneers: Power and Politics in Exclusion Era Photographs,” Ekalan Hou wrote about Lai Yong’s photograph as follows:

In Lai Yong’s . . . carte de visite of Cantonese opera performers at his San Francisco studio, a mou daan (female warrior) sits beside a siu sang (young scholar) and wraps her left arm around his shoulder. While the siu sang’s outspread legs recall Chinese ancestor portraits—a genre of painting that Western photographers working in China appropriated to emphasize the exoticism of their subjects—the actors’ eye contact and physical proximity stage an alternative to the stiff impersonality of ethnographic types. The fabric draping from the siu sang’s waist gives the impression that the mou daan has crossed her left leg over his right—an optical illusion that deepens their intimacy. In 1882, the year the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, Lai moved back to Guangzhou and opened a photo studio that offered portraits of Chinese people in “American costumes.” He used clothing as a means of imagining a fluid, transpacific citizenship.

[updated 2022-5-15]

3 notes

·

View notes