#Quong Lee & Co.

Text

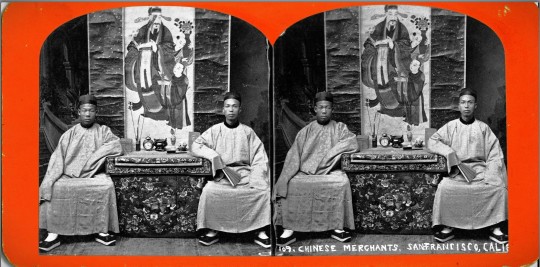

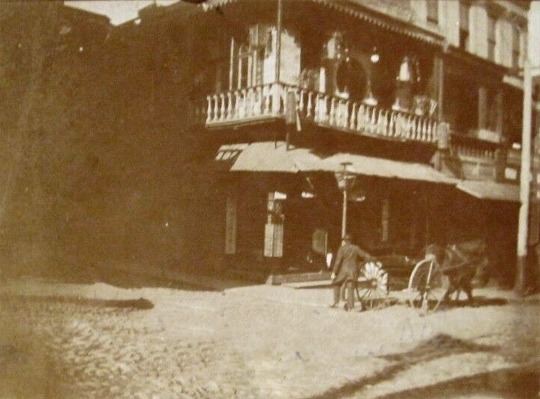

“109. Chinese Merchants, San Francisco, Calif.” c. 1890 – 1899? Stereograph by Nesemann Woods Gallery, Marysville CA (from the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung Collection of the University of British Columbia Library).

Merchants of Old Chinatown

In the late 1840s and the 1850s, Chinese merchants and traders made their initial foray into California. By February 1849, the number of Chinese had increased to 54 and by January 1850, historians would count 787 men and two women in San Francisco. In December 1849, the Alta California newspaper reported that 300 Chinese convened a meeting at the Canton Restaurant on Jackson Street for the purpose of organizing the “Chinese residents of San Francisco” and engaging the services of lawyer Selim E. Woodsworth to “act in the capacity and adviser for them.”

In his book, Genthe’s Photographs of San Francisco’s Old Chinatown, historian John Tchen wrote about the vanguard of old San Francisco Chinatown’s merchant elite as follows:

“These pioneers hailed primarily from the Sanyi (Saam Yap) or Three Districts [三邑], as well as the Zhongshan area in the immediate vicinity of Canton. It's important to note that Nanhai (Namhoi) and Panyu (Punyu) stood out as the most prosperous districts within Guangdong Province. Their economic pursuits ran the gamut from cultivating fertile agricultural lands, breeding silkworms and fish, to crafting silk textiles, producing ceramics for both domestic and international markets, and engaging in various other commercial endeavors.

“What set apart the merchants and artisans from Sanyi and Zhongshan was their mastery of a more refined city dialect compared to their Siyi (Sei Yap) counterparts, who mainly consisted of poorer, rural communities. Remarkably, over 80 percent of Chinese immigrants in North America originated from the Siyi [四邑] region. A noteworthy portion of these Sanyi merchants belonged to the emerging class of compradores, individuals who facilitated business transactions on behalf of Western trading companies. These California-based Sanyi merchants thus brought prior experience in dealings with Western entrepreneurs, and California was seen as a promising arena to expand these lucrative connections.”

With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in May of 1869, the more sophisticated and adventurous members of San Francisco’s pioneer Chinese merchant community would begin exploring other cities in the United States in search of opportunity.

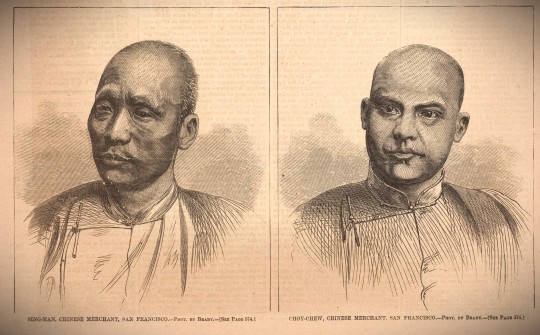

“Sing-Man, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco” and “Choy-Chew, Chinese Merchant, San Francisco,” Harper’s Weekly, September 4, 1869, wood engraving on paper. Artist unknown, artist after a photograph by Mathew Brady, 1869 (from the collection of the National Portrait Gallery).

For example, in the Harper’s Weekly article (Sept 4, 1869, page 574), the reporter identified merchant Choy Chew as a San Franciscan and a talented linguist of sufficient intellect and stature to be invited to give a speech at a European-American banquet. He reportedly visited Chicago with a fellow merchant, Sing Man, before traveling to New York where the pair were regarded as “representatives of Chinese industry and commerce.”

At the banquet in Chicago, Choy Chew delivered the following remarks:

”Eleven years ago I came from my home to seek my fortune in your great Republic. I landed on the golden shore of California, utterly ignorant of your language, unknown to any of your people, a stranger to your customs and laws, and in the minds of some an intruder — one of that race whose presence is deemed a positive injury to the public prosperity. But gentlemen, I found both kindness and justice. I found that above the prejudice that had been formed against us, that the hand of friendship was extended to the people of every nation, and that even Chinamen must live, be happy, successful and respected in ‘free America.’ I gathered knowledge in your public schools; I learned to speak as you do; and, gentlemen, I rejoice that it is so; that I have been able to cross this vast continent without the aid of an interpreter; that here in the heart of the United States I can speak to you in your own familiar speech, and tell you how much, how very much, I appreciate your hospitality; how grateful I feel for the privileges and advantages I have enjoyed in your glorious country; and how earnestly I hope that your example of enterprise, energy, vitality, and national generosity may be seen and understood, as I see and understand it, by our Government …

”We trust our visit, gentlemen, may be productive of good results to all of us; that the two great countries, East and West, China and America, may be found forever together in friendship, and that a Chinaman in America, or an American in China, may find like protection and like consideration in their search for happiness and wealth.“

-- from the Scientific American, new series, vol. 21, no. 9, p. 131 (August 28, 1869)

The founding in 1888 of the Merchants’ Exchange in old San Francisco Chinatown represented the logical culmination of several decades of robust business operations by the pioneer Chinese merchants in the city and beyond.

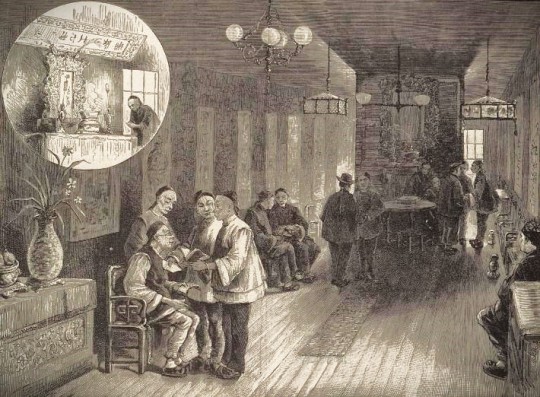

“Chinese Merchants’ Exchange, San Francisco.” Lithograph from Harper’s Weekly, Vol. 26, March 18, 1882 (from the collection of The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

In his book, A Guide Book to San Francisco (published by The Bancroft Company in 1888), John S. Hittell described the Chinese Merchants Exchange as follows:

“At 739 Sacramento Street are the new rooms of the Chinese Merchants' Exchange. They are fitted up in the ordinary Chinese style, and though presenting no special attraction to the visitor, the business transacted there is of considerable importance. A Chinese merchant, contractor, or speculator never starts on any enterprise alone. He always has at least one partner, and in most cases several. He makes no secret of his transactions, but converses about them at the exchange, and often goes there in search of capital when his own means are insufficient. He sometimes applies to that institution to find him a capable man to manage a new business which he is about to start. If, as often happens, one be selected who is in debt to other members, they make arrangements which will not interfere with the new enterprise; and the debtor is not unfrequently released from his obligations.”

Fung Tang

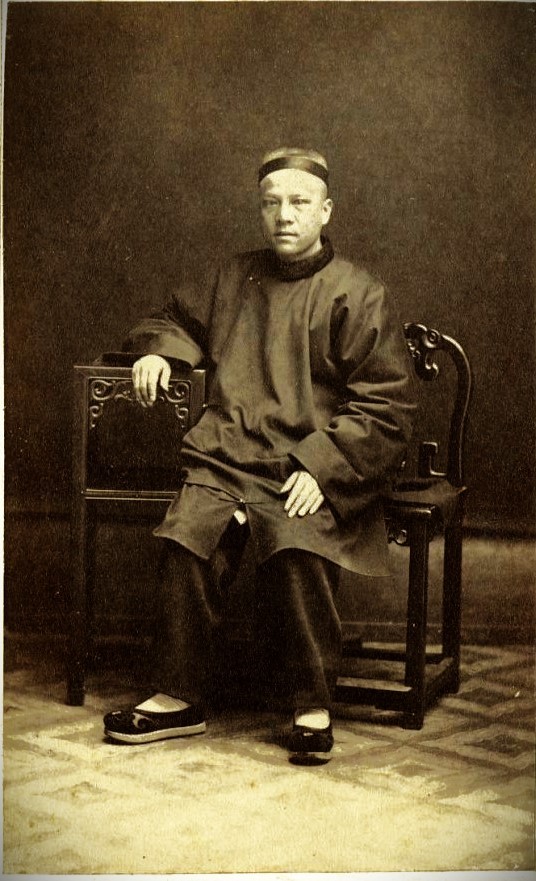

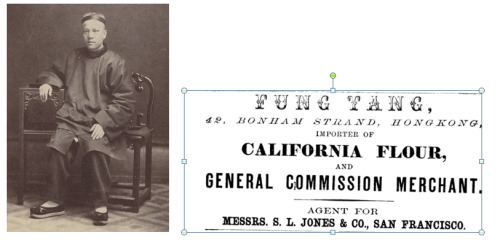

Fung Tang, c. 1870. Photo by Kai Suck (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

The address of the Merchants’ Exchange at 739 Sacramento Street was hardly surprising, as it shared the same building which had housed the mercantile house of a legendary merchant, Fung Tang. Historian York Lo, in his article for The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group website, described Fung as “a native of Jiujiang (Kow Kong) in the Nanhai county (南海九江) in Guangdong, Fung Tang followed his uncle Fung Yuen-sau (馮元秀) to California in 1857 at the age of 17 and worked at Tuck Chong & Co (德祥號辦莊), a trading business founded by his uncle and his fellow Nanhai native Kwan Chak-yuen (關澤元).” In the Langley San Francisco directory of 1868, the Tuck Chong & Co. is listed as “(Chinese) merchants” located on Chinatown’s first main street at 739 Sacramento Street.

“In his spare time,” York Lo writes, “he learned English from Reverend William Speer and became fluent in the language. With his linguistic skills, he became a bridge between the Chinese and the white community in San Francisco and even befriended Peter Burnett, the first Governor of California, who described Fung in his memoir as ’a cultivated man, well read in the history of the world, spoke four or five different languages fluently including English, and was a most agreeable gentleman, of easy and pleasing manners’.”

As such, Fung Tang must be considered as a logical client for the pioneer Chinatown photographer, Kai Suck. A professional studio portrait would have conferred respectability in the eyes of the non-Chinese businessmen and politicians with whom he interacted. In fact, Fung appears to have deployed the same portrait now reposing in the collection of the California Historical Society as part of his commercial advertising in Hong Kong.

An advertisement for Fung Tang’s flour import business in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong.

For more details about Fung’s business exploits and his public service, including his election to the board of directors of the Tung Wah clinic (the original predecessor organization of the future Chinese Hospital), readers are encouraged to read York Lo’s piece here: https://industrialhistoryhk.org/fung-tang-the-firm-the-family-the-transpacific-metals-trade-and-tin-refinery/?fbclid=IwAR3DU6pEcaEw6w2uH1OZvFBFL8vg-Rl4keBS-VkbcttFuHKlx973g3ZjcY8

Tchen asserts that the influx of British and other Western imperialist powers into China’s major treaty ports transformed the status of merchants engaged with Western trading companies. Rather than operating on the margins of Qing-era society, the merchants gained unprecedented prestige and influence. Beyond China's borders, they experienced far more freedom to engage in trade and amass substantial profits without the worry of state-imposed restrictions. They rapidly acquired the necessary language skills and business acumen to navigate their newfound opportunities.

San Francisco’s early Chinese merchants swiftly grasped the English language and American business practices, excelling in American-style transactions, and developing strategies for fostering positive relations with the general San Francisco populace. The local press affectionately labeled them "China Boys." They made conscious efforts to participate in the celebrations of significant American holidays, further endearing themselves to the San Francisco community.

This approach significantly bolstered their rapport with the local population, as evidenced by the California Courier's glowing praise: “We have never seen a finer-looking body of men collected together in San Francisco. In fact, this portion of our population is a pattern for sobriety, order, and obedience to laws, not only to other foreign residents, but to Americans themselves," declared Cornelius B. S. Gibbs, a marine-insurance adjuster, in 1877. Gibbs emphasized the high esteem in which Chinese merchants were held among white business circles. “As men of business, I consider that the Chinese merchants are fully equal to our merchants. As men of integrity, I have never met a more honorable, high-minded, correct, and truthful set of men than the Chinese merchants of our city.”

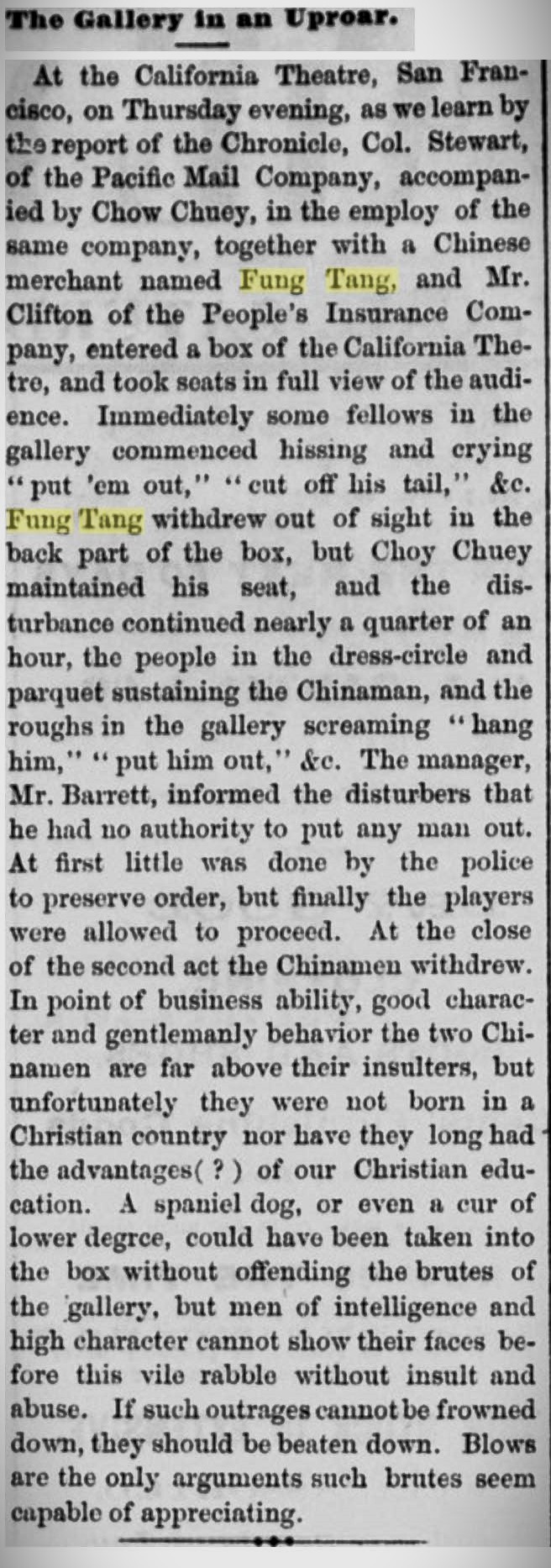

Attempts to participate in mainstream society, however, were not always welcomed by lower-class elements of white society as evident in this news account about Fung Tang’s appearance in San Francisco’s California Theatre in September 1869:

Clipping from the San Jose Mercury News, September 18, 1869 (vol. I no. 42)

Fung Tang’s transpacific success in San Francisco was hardly unique among the ranks of Chinatown’s early merchant class. He exemplified the business acumen of his fellow pioneering entrepreneurs and their establishment of transpacific trading posts in strategic locations.

Lai Chun-chuen and Chy Lung Co.

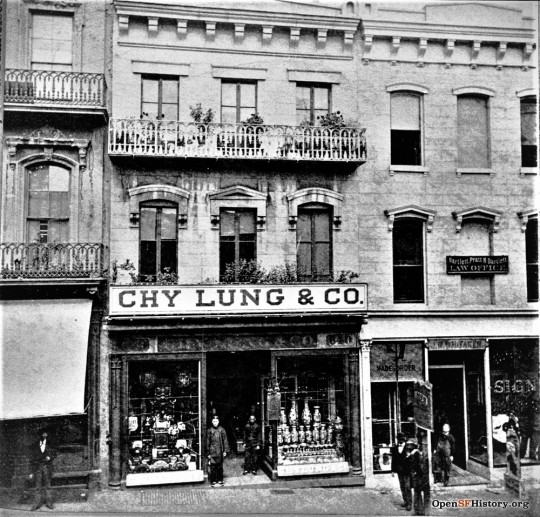

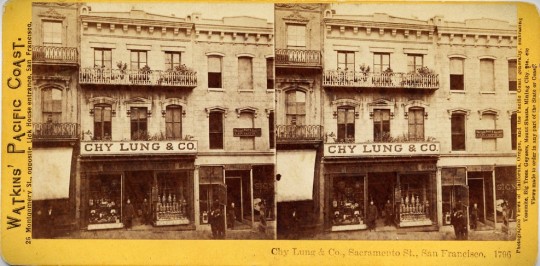

The story of the pioneer business of Chy Lung & Co. predates the history of San Francisco Chinatown itself, and its establishment spurred the rise of Chinatown’s first commercial strip, Sacramento Street (唐人街; canto: “Tohng Yahn Gaai”) or “Chinese Street.”

An enlargement of the stereograph taken by Carleton Watkins for the Thomas Houseworth & Co., and “[e]ntered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866 by Lawrence & Houseworth, in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the Northern District of California.”

“Among the early Chinese settlers were merchants like Lai Chu[sic]-chuen,” the late historian Judy Yung wrote in her pictorial book, San Francisco’s Chinatown (published by the Chinese Historical Society of America). “Upon arrival in 1850, he opened Chinatown’s first Bazaar at 640 Sacramento Street, importing teas, opium, silk, lacquered goods, and Chinese groceries.”

"Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento St., San Francisco. 1796" c. 1866. Photograph by Carleton Watkins for his Watkins' Pacific Coast stereograph series (from a private collection).

Chy Lung’s founder, Lai Chun-chuen (a.k.a. Chung Lock), came to San Francisco in 1850 from Nam Hoi county. According to UC professor Yong Chen, the business founded by Lai and, his partners Xie Mingli, Fang Ren, Sheng Wen, and Chen Nu, appear in the earliest business directories for San Francisco. A “Chyling, china mer, 188 Washington” appears in the Parker directory for 1852-1853. The Colville’s directory of 1856 lists a “Chy Lung (Chinese) mcht, Canton Silk and Shawl Store, 166 Wash’n,” and the business would remain on Washington Street (moving to 612 Washington St. by 1858) until 1863 when it relocated to 642 Sacramento Street. By 1865, the Chy Lung & Co. had either expanded or taken over the address of 640 Sacramento Street.

Portion of the stereograph “No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co.,” c. 1866. Published by Lawrence & Houseworth (from in the collections of the Society of California Pioneers, Wells Fargo Corporate Archives, and the Library of Congress).

“He imported Chinese prefabricated houses and cargoes of Chinese goods, teas, silk, lacquer and Porcelain wears, and even opium,” historian Phil Choy wrote. “The drug that made American merchants millionaires in the China trade now found its way to California for both the Chinese and American markets Chy Lung was one of only two Chinese businesses at the time that advertised in an American newspaper, the Daily Alta California.”

“No. 391 Chinese Store. Chy Lung & Co., Sacramento Street.” c. 1866. Published by Thomas Houseworth & Co. (from in the collection of the New York Public Library).

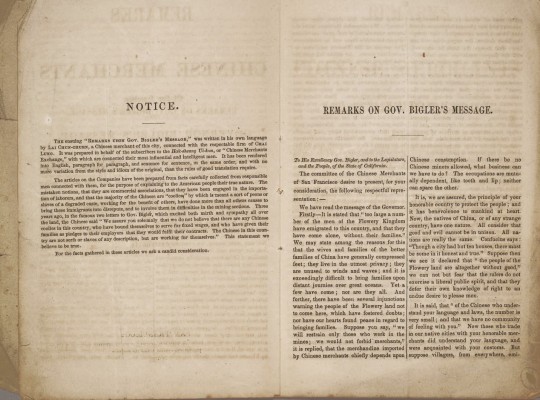

Lai Chun-chuen is remembered not only for his business acumen but also as the principal author of the objections to the anti-Chinese movement in California and plea for civil rights as published in the pamphlet, Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco, upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections (San Francisco: Whitton, Towne, 1855).

The preface to Remarks of the Chinese Merchants of San Francisco upon Governor Bigler’s Message, and Some Common Objections of 1855 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The second line of the first paragraph identifies Lai Chun-chuen as “a Chinese merchant of this city, connected with the respectable firm of CHAI LUNG.”

Chy Lung & Co. continued to play a leading role in the Chinese merchants exchange until Lai Chun-chuen’s death on August 30, 1868. The business remained a fixture of the Chinatown business community for the rest of the 19th century, and it adopted the new communications technology of the telephone, as shown by the Pacific Telephone directory for the Chinese Exchange in 1902.

The listing for Chy Lung & Co. as it appeared in the Wells Fargo directories of Chinese business for 1878 and 1882.

The Chy Lung & Co. business, and others established by Chinatown's merchants, soon comprised a source of both tangible and symbolic power within the rapidly growing Chinese community in the American West. As the Chinese immigrant population swelled, businesses catering to their specific needs diversified and expanded. A hierarchical structure emerged, influenced by both economic factors and the district of origin. The wealthier Sanyi individuals typically presided over larger, commercially successful enterprises, including import-export firms. Those from the Nanhai District dominated the men's clothing and tailoring sector, as well as butcher shops. The neighboring Shunde District populace exercised control over overalls and workers' clothing factories.

“S.F. Chinatown 1898 C12”. Photographer unknown (from the Martin Behrman Collection of the San Francisco Public Library). A well-attired merchant and possibly his son walk south on Spofford Alley from Washington to Clay Street.

Meanwhile, Chinese hailing from the Zhongshan District, which represented the second-largest Chinese population in California, were prominent in the fish and fruit orchard businesses, as well as in the production of women's garments, shirts, and underwear.

"Quan Quick Wah"

“Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). A descendant of the large, confident man shown in traditional robes identifies him as San Francisco merchant “Quan Quick Wah.” Based on other photographs of this Chinatown location, the pair appears to be walking on the west side of Waverly Place toward its intersection with Clay Street. In his book about Genthe’s Chinatown photographs, historian Jack Tchen wrote about this imposing figure followed by a bodyguard as follows: “The powerfully built man dressed in traditional silk robes has been described as a tong leader. Whether he was a tong leader, a wealthy merchant, or both, his dress and carriage convey a strong presence. Tong leaders came to rival the power of wealthy merchants. The man following the merchant or tong leader is said to have been his bodyguard, protecting him from the attack of a rival tong. In the photograph the two are passing under ornate cloth lanterns that indicate a pawnshop business.”

"Merchant and Bodyguard” c. 1896 – 1906. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the collection of the Library of Congress). This full photograph in the Library of Congress shows that Genthe’s image fortunately included a portion of the sign for the entrance to a basement restaurant. The signage (which appears in other photographs of this area), indicates that the merchant and bodyguard were photographed walking on the west side of Waverly Place (at about no. 23 and 25 Waverly) and toward the southwest corner of its intersection with Clay Street. Tchen’s guess that the background store frontage was a pawnshop is probably correct, as the “Qung Hing Art Co.” pawnshop occupied space at 25 Waverly during the 1890s. The headquarters of the merchant-controlled, Ning Yung district association was located at 23 Waverly.

Yee Ah-Tye

In old Chinatown, merchants’ personal use of bodyguards or alliances with fighting tongs were common. The organization and fragmentation of district and clan associations, along with sharp business competition, often placed lives, as well as livelihoods, at risk. For example, the Kong Chow association traced its origin to about 1853, when the influential community leader, Yee Ahtye (a.k.a. “George Athei”) persuaded members of his Yee clan of Sunning, which had remained in the Sze Yup Co. (after a number of clans split off to organize today’s dominant Ning Yung Association), to finally secede. The action by the Yee clan was joined by clans from Hoiping and Enping counties after a dispute over the presidency of the Sze Yup Co. in 1862. The resulting new association, the Hop Wo, soon challenged the merchant Ah-Tye for the custody of a piece of land on which Ah-Tye had allowed the Sze Yup Association to build a headquarters building. Yee eventually deeded the land to a new Kong Chow Association, which his fellow Sunwui merchants founded in 1866. The dispute over this property raised to such a level that Yee and his associates were compelled to organize a secret society, the Suey Sing Tong, to protect the asset and enforce his decision.

Portrait of Yee Ah-Tye (courtesy of the Chinese Six Companies). Yee was an elite merchant of Chinatown and was considered a co-founder of the Suey Sing Tong.

Born around 1829 in Guangdong province, Yee Ah-Tye had arrived in San Francisco just before the gold rush at around 20 years old. In spite of his humble beginnings, Yee had learned English in Hong Kong and swiftly ascended to a position of authority within the influential Sze Yup [pinyin: "Siyi"] Association. The Sze Yup Association, along with similar Chinese district associations, played a crucial role in assisting newly arrived Chinese immigrants during the 19th century. The organizations provided accommodation and job opportunities.

Aside from his many business accomplishments, Yee famously cross paths with the legendary, San Francisco madam Ah Toy. The conflict arose when Ah Toy accused Yee of demanding a tax from her prostitutes on Dupont Street. Despite her origins in China, Ah Toy had by then lived in America for three years and become familiar with its legal system. She boldly threatened to take legal action against him, a move she would not have dared to undertake in China.

The August 1852 report in the Daily Alta California newspaper highlighted Ah Toy's shrewdness, emphasizing her knowledge of living in America and her ability to navigate the legal system. She resided close to the police station, fully aware of where to seek protection, having faced legal proceedings herself numerous times. The reporter gleefully suggested that Yee use caution about overstepping his authority, warning that he might lose his dignity and end up in custody.

A year later, Yee faced legal trouble himself, being arrested for assault and grand larceny. The San Francisco Herald alleged Yee “inflicted severe corporeal punishment upon many of his more humble countrymen … cutting off their ears, flogging them and keeping them chained for hours together.”

After moving to Sacramento in 1854, Yee also relocated his business activities in 1860 to La Porte, California, where hydraulic and drift mining operations for gold occurred. Yee acquired a partnership in a store called Hop Sing & Company which supplied merchandise and Chinese contract laborers. By 1866, it was the richest Chinese store in that town, with a value of $1,500 (about $36,000 in 2005 dollars).

According to one of his descendants, Lani Ah Tye Farkas, the pioneer Yee Ah Tye reportedly lived thirty-four years in La Porte as a successful merchant, running the Hop Sing and Company store and representing the Chinese community in the area. He had three wives and four children, three of whom were girls. Unlike most other Chinese fathers at the time, he invested in the education of his daughters – he even bought a piano for his youngest daughter, Bessie, who became an accomplished pianist. As a leader in the Hop Sing Association, he founded a small hospital to serve the elderly Chinese men of La Porte.

“The temple ruins at San Francisco's Lincoln Municipal Park Golf Course was once part of the Lone Mountain Cemetery, a gift of Ah Tye,” Lani Ah Tye Farkas wrote in 2000. “Other glimpses of his life in America can be seen in deeds, mining claims, tax assessments, newspaper articles, and land that he once owned. Yee Ah Tye's legacy, however, is in his descendants. Many Chinese with common last names like Chan, Lee, and Wong may have no relationship with one another. However, the descendants of Yee Ah Tye have borne his unique last name through six generations, in the words of the Yee family genealogy, ‘spreading like melon vines, increasing continuously’” Yee died in 1896. (see: https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/pc289j76z)

Contract Labor

At the lower end of the business hierarchy, the Siyi or Four District residents comprised the largest and least affluent group of Chinese immigrants. They typically occupied occupations such as laundries, small retail shops, and restaurants and the bulk of the laborers in the contract labor system.

In the period preceding the Civil War, there was a concerted effort by certain individuals to introduce contract laborers into the United States. A letter penned by C. V. Gillespie to Thomas Larkin on March 6, 1848, sheds light on this initiative. Gillespie expressed a keen interest in the idea of bringing Chinese emigrants to the country, suggesting that a variety of skilled workers and laborers could be sourced:

"One of my favorite subjects or projects is to introduce Chinese emigrants into this country,… Any number of mechanics, agriculturists and servants can be obtained. They would be willing to sell their services for a certain period to pay their passage across the Pacific…."

The practice of importing contract laborers to the United States began in the late 1840s and continued through the 1850s. However, enforcing labor contracts proved to be a challenging endeavor on American soil. A case in point involved an Englishman who, upon bringing fifteen Chinese laborers to the country bound by a two-year contract, found that they immediately reneged on their agreement upon arrival. Authorities, at the time, were reluctant to intervene in such disputes.

In 1852, Senator George B. Tingley introduced a bill in the California State legislature aimed at legalizing and facilitating the enforcement of contracts allowing Chinese laborers to sell their services to employers for periods of up to ten years at fixed wages. This proposal, however, faced significant public backlash and was ultimately defeated after a heated debate. The subsequent year saw members of Chinese companies admitting that they had initially imported workers during the early years of the Gold Rush. Yet, due to unprofitability and difficulties in enforcing labor contracts, they abandoned this practice.

“San Francisco Chinese Merchant” no date. Photographer unknown, possibly by Ann Ting Gock (from a private collection). This rare and unusual image suggests that the individual might not have been a mere merchant at all, but a member of the Chinese consular staff. He is seen wearing his 清代官帽 (canto: "ching dai gwun moe") or official's headwear. The Qing official headwear or Qingdai guanmao (Chinese: 清代官帽; pinyin: qīngdài guānmào; lit. 'Qing dynasty official hat'), also referred to as the “Mandarin hat” in English, is a generic term which refers to the types of guanmao (Chinese: 官帽; pinyin: guānmào; lit. 'official hat'), a headgear, worn by the officials of the Qing dynasty in China. The merchant is attired in a "changshan" or "changpao" or long robe. The robe worn in the photo was derived from the Qing dynasty-period "qizhuang" (the traditional dress of the Manchu people). Changshan were, and are, traditionally worn for formal pictures, weddings, and other formal Chinese events.

Credit-ticket System

Beyond the initial years, it became widely acknowledged that Chinese immigrants arrived in the United States voluntarily, free from any servile contracts or duress. Many emigrants either financed their own passage or received assistance from relatives and friends already residing in California. The prevailing method for the majority of Chinese immigrants during the 19th century was the credit-ticket system. Under this system, an emigrant would receive financial support for their passage in a Chinese port. Upon reaching their destination, the emigrant was expected to repay this debt using their future earnings. It is important to note that this system differed from the contract labor arrangement, where laborers were bound to serve for a specified duration.

The precise origins of the credit-ticket system remain uncertain. However, merchant brokers in Hong Kong were established to provide advanced passage funds, approximately forty dollars, to the emigrants. Corresponding entities in the United States were responsible for collecting these debts and aiding the newly arrived immigrants in finding employment.

Two merchants with pipes. No date, photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The stores and offices that the merchants of Chinatown had opened starting in the mid-19th century became the basis of real and symbolic power in the growing regional community of Chinese living in the American West. That power, including the ability to mobilize for social change within the narrow role afforded Chinese in the society, manifested itself in the family and district associations headed by local merchants.

“The merchant class has traditionally been the one sector of Chinese society able to foster unity and bring about social change,” wrote historian Thomas W. Chinn about the role of the merchant class in San Francisco Chinatown (and beyond). “The merchant-directors of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association must be well-established businessmen in the local community as well as outstanding members of their own family associations. They have already played a leading role in their own social circles before becoming merchant-directors, and they enjoy a great deal of respect. . . Thus the friendly corner grocer may simultaneously be the president of his family association and his district association as well as a merchant-director.”

Lew Kan

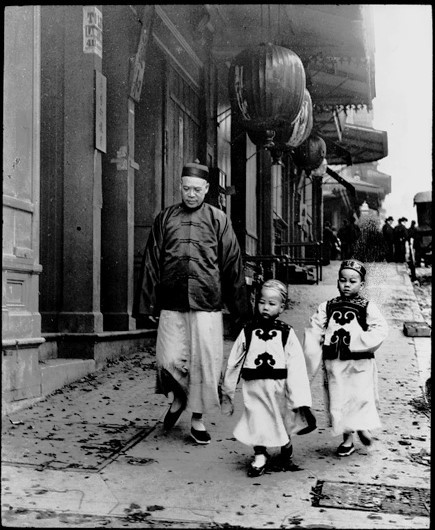

“Children of High Class” c. 1900. Photograph by Arnold Genthe (from the Genthe photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). Merchant Lew Kan (a.k.a. Lee Kan) walking with his two sons, Lew Bing You (center) and Lew Bing Yuen (right). According to historian Jack Tchen, “Lew Kan was a labor manager of Chinese working in the Alaskan canneries. He also operated a store called Fook On Lung at 714 Sacramento Street between Kearney [sic] and Dupont. Mr. Lew was known for his great height, being over six feet tall, and his great wealth. The boys are wearing very formal clothing made of satin with a black velvet overlay. The double mushroom designs on the boys’ tunics are symbolic of the scepter of Buddha and long life.” The photograph appears to have found the trio walking down the south side of Sacramento Street below Dupont Street.

By the time photographer Arnold Genthe had photographed merchant Lew Kan and his two sons on Sacramento Street (as well as two other earlier photos of their four sisters in Portsmouth Square), Lew had already attained legendary status as one of Chinatown’s leading merchants. Born in 1851, Lew entered the US in 1866.

Author Roland Hui (in his biography of pioneer Chinese American industrialist Lew Hing), wrote about Lew Kan and his dry goods business called Lun Sing & Co. at 706 Sacramento Street as follows:

“He started Lun Sing, one of the oldest businesses in Chinatown, around 1867, a year after he immigrated to the U.S. In 1896, the business gained notoriety by harboring a young Chinese revolutionary named Sun Yat-sen during his first visit to the continental United States. Sun advocated overthrowing the Qing monarchy and establishing a Chinese republic. His ideas were too radical for the politically uninitiated Chinese community. Kang Youwei, the architect of the ill-fated “Hundred Day Reform” in China in 1898, favored establishing a constitutional monarchy around Emperor Guangxu. Forced into exile after the power-hungry Empress Dowager crushed his reform, Kang launched the Chinese Empire Reform Association, also known as Baohuanghui (Save the Emperor Society), the following year in Victoria, Canada. Baohuanghui quickly gained widespread support among overseas Chinese since the idea of having an emperor at the top of the social order who ruled with the Mandate of Heaven had been ingrained in the Chinese psyche for thousands of years. The San Francisco Baohuanghui chapter was founded in 1899 at 146 Waverly Place. Lew Kan supported Kang’s political agenda despite having met Sun several years earlier, and in 1901 became the president of the San Francisco chapter of Baohuanghui. Many scholars observed that Baohuanghui was the first organization that evoked the patriotic sentiments of overseas Chinese. And when Liang Qichao, Kang's most famous student, stopped over in San Francisco during his 1903 America tour, thousands of Chinese flocked to listen to his speeches. As the man who organized these community-wide activities, Lew Kan's stature and influence in San Francisco Chinatown must have been substantial. In addition, he was one of the wealthiest Chinese merchants, reportedly owning several general merchandise stores with an estimated net worth of $2 million. That was an astronomical sum in those days. In addition, he was a director of the Kong Chow Company, a district association representing Xinhui."

Decline of Merchant Influence

The organizational expression of Chinatown’s merchant elite, the Chinese Six Companies, wielded considerable authority within San Francisco and beyond. The Six Companies and its constituent district associations comprised the quasi-government of Chinese America, offering social services, mediating disputes, and representing the community's interests to external forces. With the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882, their grip on power began to weaken.

Portrait of a merchant with fan and scroll. No date, photograph possibly by Shew’s studio (based on the detail of the end-table), from the collection of the Stanford Libraries.

The decline of the Six Companies’ influence can be attributed to various reasons. One significant factor was their inability to adapt swiftly to the evolving socio-economic landscape within Chinatown. As the community faced new challenges, including the punitive extension of Chinese exclusion with the Geary Act of 1892, the Six Companies struggled to effectively navigate these changes, leading to a loss of faith among the populace in their ability to address emerging issues.

The Geary Act of 1892 extended and strengthened the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, requiring most Chinese Americans – native and foreign-born -- to carry an internal passport in the form of certificates of identity or face arrest and deportation. It intensified discriminatory measures against the Chinese community, fostering widespread discontent and resistance.

In response, the Six Companies initiated a national boycott against the Geary Act. The boycott aimed to unify Chinese immigrants and their supporters across the United States, urging them to refuse compliance with the law as a form of protest. It gained substantial momentum, with significant participation from Chinese communities in various cities, voicing opposition to the Act's discriminatory provisions.

The board of directors of the Chinese Six Companies, no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). Based on the screen panels in the background (which remain in the Six Companies’ meeting hall at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco), the photo appears to have been taken after 1906.

Despite its initial vigor, several factors led to the ultimate collapse of the national boycott against the Geary Act. First, the federal government intensified its efforts to enforce the Geary Act. Authorities conducted widespread raids and inspections, threatening deportation and imposing harsh penalties on those failing to comply. The fear of reprisals and the potential disruption to livelihoods coerced many Chinese immigrants into reluctantly acquiescing to the Act's demands.

Second, the broader American society exhibited little sympathy or support for the Chinese community’s plight. The prevailing anti-Chinese sentiment in the country and the lack of significant political backing from other institutions diminished the effectiveness of the boycott. Without widespread solidarity, the Chinese American community struggled to sustain its resistance.

Finally, the decision by the US Supreme Court in Fong Yue Ting v. United States, 149 U.S. 698 (1893), dealt a major legal setback to Geary Act resistance and undermined the credibility of the Six Companies. The decision validated the Geary Act and created an environment of fear within the Chinese American community. The inability to overturn the Geary Act by legal means diminished trust in the Six Companies’ capacity to protect the community's interests.

Photograph of a merchant from Chinese Business Partnership Case File for Quong Lee Company, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from the files of the Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, San Francisco District Office). The immigration investigative case file indicates that the individual in this photo was certified as a business partner and a "merchant" who was “able to travel to and from the U.S. as a ‘Chinese subject of exempt class’ under the ‘Chinese Exclusion Acts’ (1882-1943).” The Quong Lee & Co. (a.k.a. Quong Lee, Quong Lee Sing) operated what business directories from 1875 to 1905 variously described as a “tailor,” “general merchandise,” “clothing,” and “dry goods” business continuously at 828 Dupont Street. By the time this merchant sat for his photo in 1896, the national boycott led by Chinese merchant organizations against the Geary Act of 1892 had collapsed, and studio portraits such as this became an essential pieces of evidence to support applications for the coveted merchant exemption from the extended Exclusion Act.

This heightened sense of vulnerability played into the hands of tongs, which, capitalized on the weakened merchant community. Amidst the faltering influence of the Six Companies, tongs emerged as influential entities that would come to dominate Chinatown’s socio-political structure and shape mainstream society’s perceptions of the Chinese community for the next three decades.

“High-binders Retreat” no date. Photograph by Goldsmith Brothers (from the Cooper Chow Collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). Tong members at ease in front of their fraternal order's headquarters.

Tongs, in contrast to the Six Companies' diplomatic approach, adopted a more assertive stance in responding to discrimination and persecution faced by the Chinese community. Their readiness to protect their members (which also included merchants), and defy external pressures resonated with many disillusioned residents.

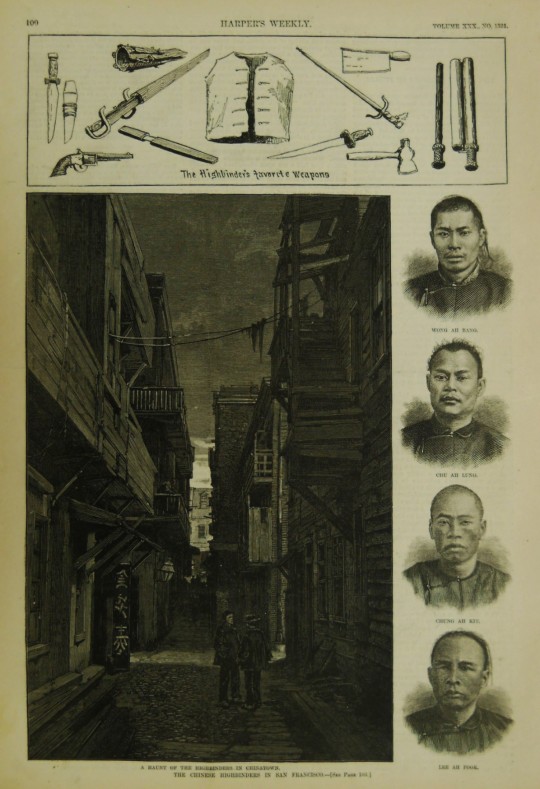

“A Haunt of the Highbinders in Chinatown.” Harpers Weekly, February 13, 1886 (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

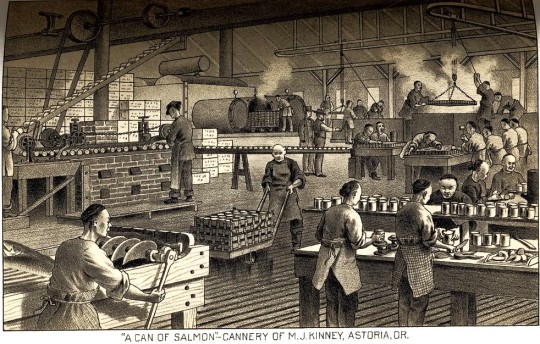

Moreover, the tongs during this period had begun to diversify their activities beyond traditional, illicitl sources of income such as prostitution, gambling, and drug distribution. Tongs began engaging in both legitimate businesses, including labor contracting for the Alaskan canneries. This diversification allowed them to accumulate resources, expanding their sphere of influence within Chinatown and beyond as alternative community governance structures, while still reserving often violent means to protect their interests.

Chinese salmon cannery works in Astoria, Oregon, c. mid-1880s. Drawing from West Shore, June 1887, from the Special Collections, University of Washington). The early 20th century would be marked by violent struggles between tongs such as the Suey Sing and Bing Kung for control over the labor contracting business for the canneries.

The ascendancy of tongs at the turn of the century coincided with the republican movement in China. Historian Phil Choy wrote that the Chee Kung Tong, the original triad society, had been evolving in response to revolutionary movements in mainland China:

“Chee Kung Tong returned to its lofty political ideologies in 1900 when both Kang Yu-wei’s Reform Party and Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Party sought its assistance. Originally the Chee Kung Tong supported Kang Yu-wei, but as Dr. Sun’s ideology gained popularity, the Chee Kung Tong, switched allegiance. When in 1904 immigration officials did not allow entry to Sun, the leader of the Chee Kung Tong, Wong Sam Ark, and the Tong’s attorney Oliver Stidger, along with Reverend Ng Poon Chew and Reverend Soo Hoo Nam Art, worked successfully for his release. Sun stayed at the Chee Kung Tong headquarters and used the society’s newspaper, the Chinese Free Press, to propagandize his revolutionary cause. Accompanied by Wong Sam Ark, Dr. Sun went on a nationwide tour to generate support and contributions.”

The tongs’ economic power and their active involvement in fundraising for the republican movement not only showcased their financial strength but also demonstrated their ability to wield influence as an overlapping and sometimes counter-force with the merchant elite. This dual role as (1) economic powerhouse within the local community, and (2) significant contributor to a revolutionary cause overseas underscored their influence. The growth of that influence came at the expense of the merchant elite in shaping both local and international affairs.

Merchants, however, would continue to exert influence through clan organizations, tongs, business associations, Nationalist Party of China chapters, and Chinese “consolidated benevolent associations” in San Francisco Chinatown and communities across North America through the exclusion era, war, and peace.

The meeting hall of the Chinese Six Companies, c. 1920 (by then incorporated as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association) at 843 Stockton Street in San Francisco. Photographer unknown (from the Jese B. Cook collection of the Bancroft Library).

Chinatown's merchant community would face new challenges to their capacity as civic leaders when the political center of gravity across US Chinatowns would shift again in the last quarter of the 20th century.

[updated 2023-12-28]

#Chinatown merchants#Sing Man#Choy Chew#Chinese Merchants Exchange#Fung Tang#Lai Chun-chuen#Chy Lung & Co.#Yee Ah-Tye#Chinese Six Companies#Kai Suck#Ann Ting Gock#Lew Kan#Chee Kung Tong#Quong Lee & Co.

0 notes

Photo

1895 - 1896 Chinese American Man's Gown

Lee B. Lok (1869-1942) immigrated to San Francisco from the Tai shan District, Guangdong Province, China in 1881. Soon after arrival he moved to New York City’s Chinatown where he worked in the Quong Yuen Shing & Co. general store.

In New York, Lee founded the Chinese Merchants Association, and in 1918 he was recognized as a prominent member of the Chinese community; however U.S. laws prohibited him from becoming an American citizen. His children all attended college becoming teachers, doctors and business people.

Lee B. Lok ordered this gown from China to wear at the 1896 arrival ceremony in New York of Li Hongzhang, emissary of the Empress Dowager of China. Soon after Lee came to America he abandoned Chinese clothes for daily use and cut his queue. However on special occasions Lee wore clothing that identified him as Chinese. This Manchu style gown splits at the back, front, and both sides to allow for easy movement on horseback – a reflection of the Manchu people’s equestrian background.

source: [Clothes and Heritage: Chinese American Clothes of the Lee Family]

1 note

·

View note

Photo

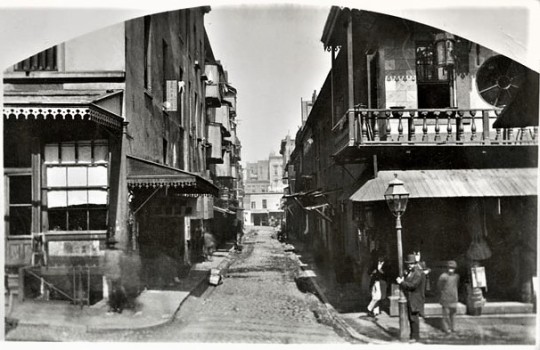

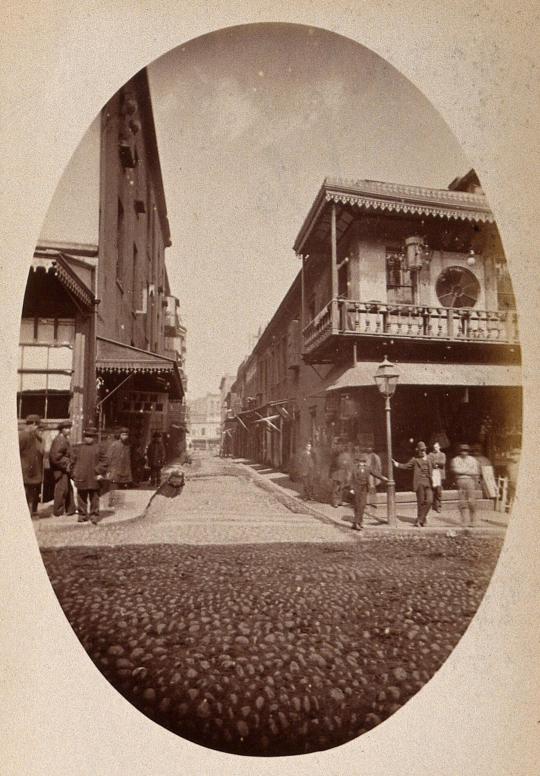

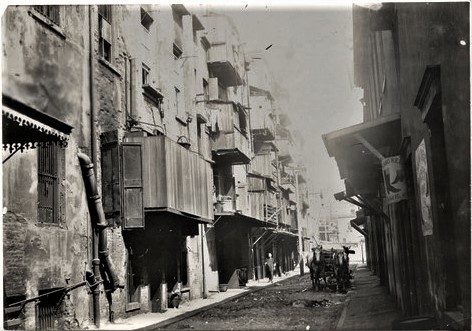

“Bartlett Alley, Chinese Quarters, S.F. 3751” c. 1870. Stereograph by Carleton Watkins (from the New York Public Library Digital Collection).

A Troubled Way: Old Chinatown’s Bartlett Alley

Certain streets and alleys of America’s major Chinatowns occupy a long and troubled place in the history, and minds, of Chinese America. The mere mention of the names can trigger expressions of shame when recounting the sordid and sanguinary misdeeds of the ghetto economy and its underworld.

Nineteenth century newspapers regularly reported about the murder and mayhem committed in the small streets of the community by criminals and organized criminal interests over control of gambling, prostitution, opium dens and labor racketeering. The stories would infect Americans’ attitudes and opinions about Chinese Americans for decades, and the stereotypes that emerged from Chinatown’s criminal history continue to burden the community with adverse publicity even in this century.

Having come of age when the legitimacy of the Chinese America a half-century after the Exclusion Act, the writings of Thomas Chinn of the Chinese Historical Society of America and his colleagues barely concealed their sense of embarrassment at Chinatown’s criminal history -- choosing instead to focus on the “contributions” of the Chinese to the building of the American West and the political economy of the US. However, the work of the late Kevin Mullen, a criminal justice historian and retired deputy chief of the San Francisco Police Department, tells a different story that tong violence arising from contests for control of the rackets – as measured by Chinese homicide rates -- continued well after the 1906 earthquake until 1920.

The serious study about the role of organized crime and operations as integral to the segregated, ghetto economy of Chinatowns remains to be written. However, that is a story for another day, as the focus of this comment is Bartlett Alley or 白話轉街 (canto: “bak wah chuen gaai”), now known as Beckett Street in modern day San Francisco Chinatown.

“Chinatown [Bartlett] Alley” c.1870s, as viewed north from Jackson Street. This wider angle photograph shows Chinese men are seen on west or left side of the street, and Caucasian men occupying the northeastern corner of the intersection. (Photo by Carleton Watkins from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

“Highly colored accounts of the Chinese highbinders are to be found in nearly every library,” wrote Thomas Chinn. “Most have been dramatized beyond their just desserts.”

This item from the Daily Alta California (Volume 27, Number 9151), from April 23, 1875, represented an example of the type of police blotter reportage generated by the mayhem, homicide and prostitution in Bartlett Alley:

A HEATHEN MISSIONARY

“Last night word was taken to the Police Office that a murder had been committed in Chinatown. Officer McCaffrey was sent to look it up. When he reached that festering quarter, Bartlett Alley, he found a chattering multitude of the denizens surrounding a dirty den, and on the inside a war of discordant sounds seemed to indicate that murder most foul was still being done. The officer put his boot through the door and got into the midst of the yelping set. There be found that some model moralist of the heathen swarm had undertaken in his virtuous Indignation to break up the den that is conducted by Joss-forsaken females. This apostle of virtue was received with open arms to a bloody treatment having had his head remodelled after the most approved and barbarous fashion by the aroused inmates, who used their earthenware utensils with great precision as projectiles. This was about all the damage, and the wounded, steered by the officer, went downward to the prison where Dr. Stivers treated him kindly.”

“Bartlett Alley, Chinese Quarter, San Francisco” c. 1870. Photograph by Carleton Watkins from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection. The view north on Bartlett Alley from its southerly Jackson St. end. Chinese men can be viewed at right, and Caucasian men on the opposite northeastern corner.

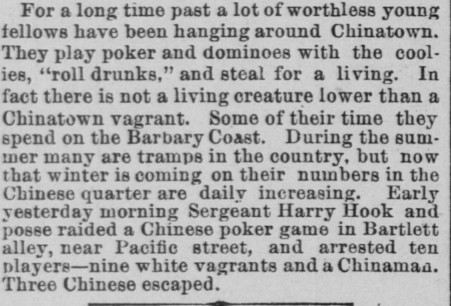

The prominent photographer, Carleton Watkins, apparently took a second photo at what appears to have been at mid-day on Bartlett alley from his vantage point looking north on Bartlett from the south side of Jackson Street. Watkins photo, which included the images of white men -- loitering on the northeast corner of the intersection of Bartlett Alley and Jackson – also serves as evidence that Bartlett Alley’s gaming and other entertainment businesses also catered to whites. A report in the Daily Alta California (Volume 81, Number 113), on October 21, 1889, reported on the seasonal aspect of white patronage and criminality in the alley as follows:

Nine Chinatown Vagrants.

For a long time past a lot of worthless young fellows have been hanging around Chinatown. They play poker and dominoes with the coolies, “roll drunks,” and steal for a living. In fact there is not a living creature lower than a Chinatown vagrant. Some of their time they spend on the Barbary Coast. During the summer many are tramps in the country, but now that winter is coming on their numbers in the Chinese quarter are daily increasing. Early yesterday morning Sergeant Harry Hook and posse raided a Chinese poker game in Bartlett alley, near Pacific street, and arrested ten players— nine white vagrants and a Chinaman. Three Chinese escaped.

“Bartlett Alley, Chinese Quarter, S.F. 3752” c. 1870. Watkins’ New Series stereograph by Carleton Watkins from the collection of the California Society of Pioneers and the Bancroft Library.

In Watkins’ stereograph no. 3752, the group of white men standing outside the saloon at 642 Jackson Street on the northeast corner had grown to perhaps eight onlookers. In the meantime, the number of curious Chinese men at the opposite northwestern corner had grown to at least five, and they are gathered in front of the storefront at 644 Jackson Street.

By 1870, white attitudes toward, and segregation of, the Chinese were hardening with the worst years to come. One Chinese man, walking up and west on Jackson Street is entering the frame from the extreme right, but he would have been unlikely to pause and look at the photographer until after crossing to the presumably safer opposite corner.

Although Watkins’ photo perhaps subconsciously captured the degrees of separation between Chinese and white men of the early 1870’s on the street, the separation did not extend to the entire building at 642 Jackson Street on the northeastern corner. The view of the second floor balcony shows a very common design of Chinese lantern.

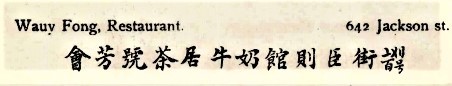

A close-up of the restaurant signage on the second balcony of the building seen in the photo “Bartlett Alley, Chinese Quarter, San Francisco” c. 1870 by Carleton Watkins (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection).

A closer inspection of the building in Watkins’ photo reveals a large sign appears over the large circular window in the center of the façade at the balcony level. The Chinese characters appear to read from right to left as a restaurant name (in the modern left-right order: 會芳樓 canto: ”Wui Fong Lauh”). According to its listing in the 1878 Wells Fargo Chinese business directory, the full name of the eating establishment as listed was 會芳號茶居牛奶館則 (canto: “Wui Fong houh cha geui ngau nai gwun”).

The listing for “Wauy Fong Restaurant from the 1878 Wells Fargo Bank Chinese business directory. The Chinese characters, 會芳號, indicate that the restaurant served Wauy Fong-branded tea and milk beverages.

Unfortunately, the business directories of the time provide negligible insights about the other occupants of of 642 Jackson Street (on the northeast corner of Bartlett Alley and Jackson Street as seen in Watkins’ stereograph).

The OpenSFhistory.org website speculates that the above stereograph depicts “Grant Avenue near Sacramento” c. 1870. A closer viewing, however, indicates that the center of each frame shows the same corner building captured in Watkins’ photos from directly across the street. This photo appears to have been taken from a point west of Bartlett Alley’s T intersection with Jackson Street and looking east down Jackson Street’s modest incline. The architectural features of the building are substantially the same shown in Watkins’ photos with the ground floor saloon and upstairs Chinese restaurant (with its distinctive circular window) were located. The figure of a white man standing in the shade of the awning and back away from the curbside lamp post could be the same hat and suit-clad individual shown leaning against the lamp post in the Watkins photos.

The 1871 Langley directory shows a “Delos Woodruff, special policeman” living at 642 Jackson Street. As an early adopter of early photograph technology for law enforcement purposes, Woodruff remains an interesting figure in the history of old Chinatown and a sort of pioneer of the police surveillance state.

Although Woodruff may have served as an officer for the San Francisco Police Department (”SFPD”), the directory’s listing him as a “special policeman” indicates that he worked in the early 1870’s as a city-authorized “rent-a-cop.” As historians of the SFPD will attest, the “patrol specials” have augmented the SFPD’s ranks of full-duty sworn officers since the city’s beginnings when the city charter provided merchants with the option of paying for private security services within designated areas. Woodruff’s apparently aggressive pursuit of criminal suspects in Chinatown gained him notoriety to such an extent that his resignation as a special in 1874 was reported in the Daily Alta California (of December 7, 1874) under the headline “Resignation of Local Officer Woodruff.” "His specialty,” the paper noted, “was looking after Chinese thieves, in which he was most successful, and indeed he was looked upon as the head and front of the Chinese specials whenever any important duty was to be performed in that branch of the police service.“

Even after his resignation, the Bishop directory of 1875 (pg. 1074) listed Woodruff as a “special policeman” still residing in Chinatown at the International Hotel which was located at 824-826 Kearny Street. However, he didn’t reside there for long, as subsequent directories omit any reference to Woodruff.

Woodruff left behind for future historians a leather-bound album containing identification photographs of Chinese men and women (some identified by name) in San Francisco from 1872 onwards. The album, which includes some inscriptions in pencil indicating names, crimes, and sentences, has reposed in the collection of the California Historical Society (“CHS”) since 1949.

The building at 642 Jackson Street on the northeast corner with Bartlett Alley, c. 1870. Photographer unknown. Is the ever-present white guard on the corner patrol special officer Delos Woodruff?

Ekalan Hou wrote about Woodruff for a photographic exhibition by CHS in 2022 as follows:

“Delos Woodruff (1834-1893), a police officer whose specialty according to the San Francisco Alta was catching Chinese thieves, kept a “mug-book” of those who he apprehended. Each leaf in his album is lined with three photographs, inscribed with the criminal’s name (if known) and the sentence they’d received— sometimes in years and sometimes with a single word: “dead.” Woodruff activated what US critic Allan Sekula calls photography’s “repressive” logic: the camera was literally used to capture and arrest Chinese subjects. But some Chinese people eluded Woodruff; for instance, Ah Ping appears three times in the album in various guises and never with a prison sentence indicated. His portraits are also pasted on the endsheets with a nickname vexedly penned—“The Cat”—a euphemism for his stealth in evading Woodruff’s surveillance.”

As a veteran of the Chinatown beat, Woodruff is often credited as the originator of the term “highbinder” in reference to the “hatchet men/boys,” “boo how doy” (Toisanese pronunciation), or 斧頭仔 (canto: “fu1 tau3 jai2”) who served as the soldiers or enforcers for the criminal tongs of Chinatown. As Richard H. Dillon wrote in his book, Hatchet Men, Woodruff was testifying in court when he declared: “A lot of highbinders came to the place—” whereupon the judge interrupted him with a gesture of his hand. “What do you mean by ‘highbinders?” Woodruff replied, “[w]hy a lot of Chinese hoodlums… .That’s what I call them.” (Dillon 21)

Thus, it would have hardly been surprising that Woodruff may have served as a convenient keeper of the peace for the white-owned grocery and saloon’s patrons while he lived at the northeast corner of Bartlett Alley and Jackson Street. The scant evidence does suggest that the three archival photos of the southern end of Bartlett Alley captured then-officer or patrol special Woodruff standing guard on his beat near the building’s corner entrance and lamp post.

* * *

The Bishop directory of 1875 also shows a “Toy Hung Lou” boarding house and a barber, “Sen Kee,” occupying space at 642 Jackson St. By 1883, the Langley directory listed a “Sun Wah & Co., restaurant” at 642 Jackson which would be consistent with the Chinese ornamentation of the second floor. However, the name does not match the signage in Watkins’ photo of a dozen years earlier. The 1885 city map itself confirms that the ground floor business premises at 642 Jackson remained under white occupancy over the dozen years since Watkins had taken his photos.

Similarly, a directory search only discloses thus far a “Lun Hing, tailor” listing in the 1875 Bishop directory as occupying the premises at 644 Jackson. Unfortunately, the name of the purported Chinese barber shop that the 1885 surveyors mapped at 644 Jackson Street remains unknown.

Bartlett Alley, view toward the south and the T intersection with Jackson Street, c. 1880. Photographer unknown

Prostitution represented the major use of the buildings on Bartlett Alley. Criminal elements often fought over the women who worked in the bordellos, as this article from the Daily Alta California (Volume 36, Number 12327), from January 14, 1884:

ATTEMPTED KIDNAPING

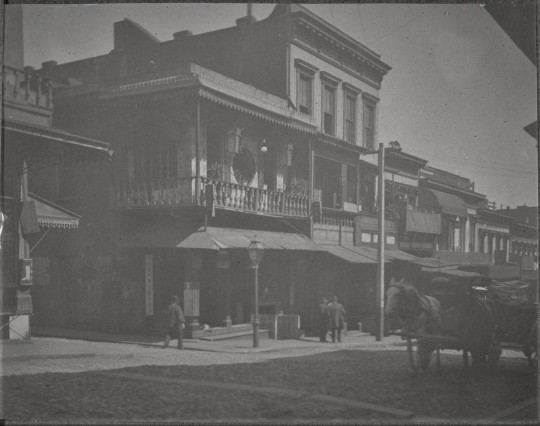

Bartlett Alley, view toward the north and Pacific Street, c. 1880. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

Bartlett Alley had already acquired its notorious reputation for criminal activities by the time a Special Committee of the Board of Supervisors began to investigate the “evils of Chinatown” in the spring of 1885. It shared the same name as then-serving Mayor of San Francisco, Washington Bartlett, and the city map makers also designated the alley as Lozier Street.

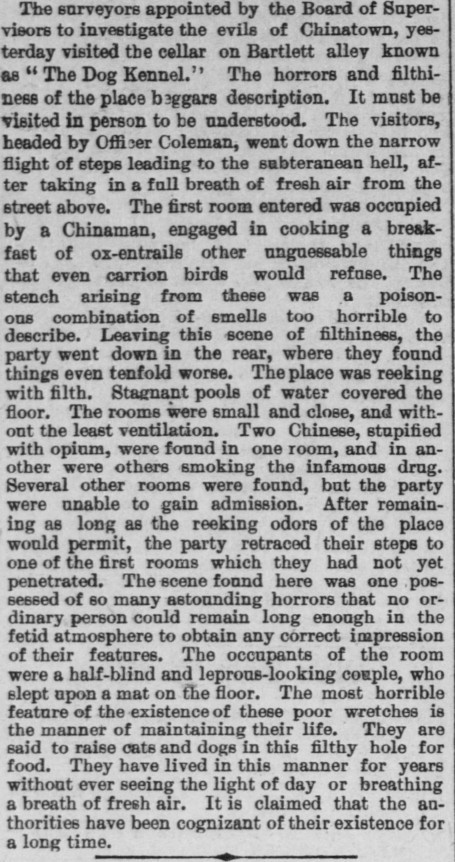

Some of the conditions observed on Bartlett Alley by the committee’s investigators in the spring of 1885 were reported in the Daily Alta California (Volume 38, Number 12754), on March 15, 1885, as follows:

INDESCRIBABLE HORRORS

Discovered by the Supervisors' Committee In Chinatown Yesterday.

When the committee’s “vice map” of July 1885 was published, no fewer than 20 “Chinese Prostitution” establishments were identified as operating on the small street and at least two gambling establishments.

Detail of Bartlett Alley from the Fifth Edition of the Chinatown Map with a special supplement to the San Francisco Daily Report, July 1885 (from the Cooper Chow collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America)

The 1885 map also appeared to have confirmed what Carleton Watkins’ photograph of the view north on Bartlett Alley from its intersection with Jackson Street disclosed – the operation of a white-owned, ground floor business establishment at the northeast corner of the intersection, which the 1885 committee identified as a “White Grocery and Saloon.”

“Tea Houses” c. 1885. Photographer unknown (from the collection of The Bancroft Library). The photo (for which the Bancroft provides scant information) centers on the northeast corner of the intersection of Bartlett Alley and Jackson Street. The circular window of the 會芳樓 (canto: ”Wui Fong Lauh”) restaurant appears set back from the balcony on the second floor façade.

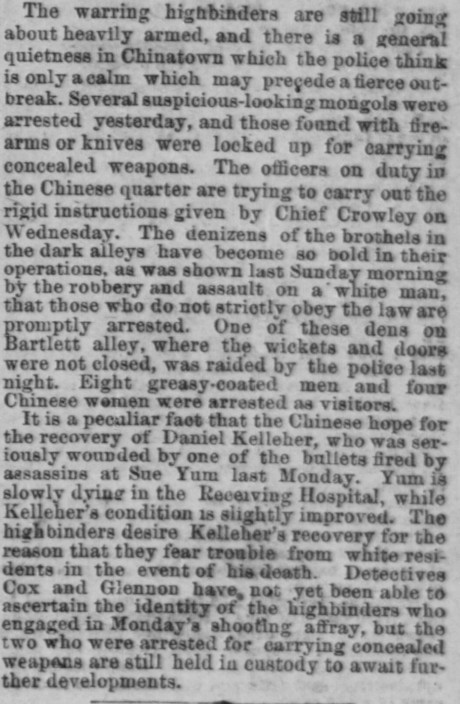

In spite of the City of San Francisco’s attempt to clean up Chinatown as a public health nuisance in 1885, the police continued to focus on the bordellos in Bartlett Alley as a source for quick and easy arrests, particularly in response to incidents when whites were caught in the crossfire of tong gunfights. A story from the Daily Alta California (Volume 80, Number 88), on March 29, 1895, typified the racial profiling by the police even as the prostitution operations were tolerated:

LAWLESS CHINESE.

A Lively Time for the Police on Duty In Chinatown.

The warring highbinders are still going about heavily armed, and there is a general quietness in Chinatown which the police think is only a calm which may precede a fierce outbreak. Several suspicious-looking mongols were arrested yesterday, and those found with firearms or knives were locked up for carrying concealed weapons. The officers on duty in the Chinese quarter are trying to carry out the rigid instructions given by Chief Crowley on Wednesday. The denizens of the brothels in the dark alleys have become so bold in their operations, as was shown last Sunday morning by the robbery and assault on a white man, that those who do not strictly obey the law are promptly arrested. One of these dens on Bartlett alley, where the wickets and doors were not closed, was raided by the police last night. Eight greasy-coated men and four Chinese women were arrested as visitors.

It is a peculiar fact that the Chinese hope for the recovery of Daniel Kelleher, who was seriously wounded by one of the bullets fired by assassins at Sue Yum last Monday. Yum is slowly dying in the Receiving Hospital, while Kelleher’s condition is slightly improved. The highbinders desire Kelleher's recovery for the reason that they fear trouble from white residents in the event of his death. Detectives Cox and Glennon have, not yet been able to ascertain the identity of the highbinders who engaged in Monday’s shooting affray, but the two who were arrested for carrying concealed weapons are still held in custody to await further developments.

The northeastern corner of the intersection of Bartlett Alley and Jackson Street, c. 1898. Photographer unknown. By 1898 (the approximate year of the above photograph), the corner premises at 642 Jackson Street appears no longer occupied by a white-operated business. The balcony appears substantially similar to the décor first seen in Watkins’ photo of a quarter-century earlier.

Although the Bartlett Alley photographs of Watkins show groups of white and Chinese men standing apart from each, newspaper accounts indicate that the criminals of races were not averse to working with each other for profitable capers. A story from the San Francisco Call, (Volume 77, Number 42) of January 11, 1895, reported about a white and Chinese burglary team as follows:

STRANGE COMBINATION.

A White Man and a Chinaman Arrested for Burglary.

Looking south on Bartlett Alley at the Quong Lee cigar company building at 32 Bartlett Alley, c. 1902-1905. Photographer unknown from the collection of the Bancroft Library.

Although the Quong Lee Co. does not appear at 32 Bartlett Alley in the Langley business directories around the turn of the century, the cigar manufacturer had a listing for the “China 315” phone number in the Chinatown Exchange telephone directories during 1902 through 1905. The city’s 1885 map recorded the location at no. 32 Bartlett Alley of a “Chinese woodyard.” The presence in the photo of a wood-laden, horse-drawn wagon in front of building implies that the property may have continued to be used as a woodyard for at least a couple of decades.

The Quong Lee Co. building photographed from a southerly angle with the address sign of the Sing Kee Co. at 28 Bartlett Alley. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). All three window enframements on the upper floor of no. 32 and 30 Bartlett Alley appear boarded up, and a female head can be seen looking out from an open wire cage window.

Although the city’s 1885 map only identified one numerical address on the east side of Bartlett Alley (i.e., the wood yard at no. 32), the southerly adjacent location (at no. 30 and 28) were identified as a “Chinese Prostitution” locations.

During the rest of the 1880’s and 1890’s, news of the murder and mayhem occurring in and around Bartlett Alley’s prostitution and gambling houses – too numerous to summarize here -- occupied space in the city’s papers almost daily. However, the alley also served as the scene of some of the many rescues of slave girls by the Presbyterian Mission and others as this article in the San Francisco Call (Volume 81, Number 132) from April 11, 1897.

WANTED TO BE RESCUED.

[the article continues]

On the way they called for the assistance of Police Officers Meredith and Duke of the Chinatown squad. The house and the women were easily found and they accompanied Miss Culbertson and the officers to the Ladies’ Mission at 920 Sacramento street. The other inmates of the Chinese resort, fearing that they, too, were wanted, made their escape by" scampering over the roofs of the adjoining buildings.

As was true for many historians of his time, Thomas Chinn of the Chinese Historical Society of America adhered to the conventional account that “[t]he highbinders’ period of greatest power was in the 1880’s up to shortly after the San Francisco 1906 disaster. Gradually, the Chinese community itself began to realize its own responsibilities. Backed by the police and courts, the Chinese worked to again establish peace and order.”

Although old Bartlett Alley would be destroyed in the Great Earthquake and Fire of 1906, newspaper accounts suggest that criminal enterprises reestablished themselves on Chinatown’s rebuilt Bartlett Alley after 1906.

A token reputedly issued by a house of prostitution located at 47-49 Bartlett Alley, c. 1908

“22 Bartlett Alley” 1905. Painting by Charles Albert Rogers (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

The brothels and cribs in Bartlett Alley finally came to end on Valentine’s Day and February 15, 1917, when San Francisco compelled their closure (along with houses of prostitution on Cooper Lane, Wentworth, the 600 block of Jackson Street, and the 700 block of Commercial Street), as part of the city’s eradication of the core of the Barbary Coast red-light district.

In spite of the clean-up campaign, the business of love for sale would simply relocate elsewhere in the city. Twenty years later, the Atherton Report found that more than 130 houses of prostitution were operating illegally in San Francisco. For the new Beckett Street of post-1906 Chinatown, however, a colorful part of its history as Bartlett Alley had finally ended.

Beckett Alley during a weekday in a Chinatown hard-hit by two years of pandemic. Photo by Doug Chan. After the 1906 quake and fire, the new building on the northeast corner of the intersection (at right) was re-numbered to 670 Jackson Street. The northwest and northeast corners are occupied respectively by the now-legendary establishments of Red's Place and the New Lun Ting Cafe (Pork Chop House).

[updated: 2022-12-30]

#Bartlett Alley#Wauy Fong Restaurant#Chinatown San Francisco#Carleton Watkins#Delos Woodruff#San Francisco Patrol Specials#Charles Albert Rogers#San Francisco Police Department#Thomas Chinn#Beckett Alley#Red's Place#New Lun Ting Cafe#Quong Lee Co.#Sing Kee Co.#Beckett St.

3 notes

·

View notes