#I think I meant it as earlier and it was understood as later or smt

Text

in french we have this fun little expression “tantôt” that can either mean “earlier” or “later” and knowing which it is is always a little deduction game based on context and verb tense

#you would think that makes it very confusing#but I use and hear that word v frequently and I can only recall one time when it was assumed to be the wrong one#I think I meant it as earlier and it was understood as later or smt#I just think it’s funny that there’s a word that technically means two mutually exclusive and opposed concepts#but when you think about it they’re p similar. the important part is that it’s always used for a little span of time#usually the same day#like if I say I’ll take care of it tantôt it’s implied that it will be later today#same if I say I took care of it tantôt#it’s interesting to think about how language is used to express our vision of the world but it also shapes it in many ways#because explaining this in english makes french sound kind of insane#but in my mind this makes perfect sense#yeah it’s about later and earlier but the core is that we’re talking about just a little bit of time

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

SMT V and mythology

While many game franchises make use of mythology to some degree, Shin Megami Tensei is arguably the only one known for extraordinary dedication to the source material, with not only designs but even major plot points often being lifted directly from mythology or at least from literature (of varying quality) pertaining to it.

In the following article I will look into how SMT V fares in that regard, relying chiefly on the portrayal of some of the plot-relevant demons, though I will also evaluate some of the central plot elements of the game.

It naturally contains unmarked spoilers.

Lahmu

Doi’s Lahmu and a terracotta relief of a Lahmu

As some of you may remember, my initial view of Lahmu was rather positive. The design, by Doi standards, at least tries to capture the essence of the creature depicted. True to the meaning of its name (which in Akkadian means “hairy one” - not “muddy one” as you might incorrectly learn here and there online), it certainly is hairy, and I guess it does look sort of like a nondescript aquatic creature (or like a globster, at least...), which fits a being often associated with the subterranean sea from Mesopotamian beliefs, Apsu (or Abzu, or Engur).

It’s not a 1:1 copy of the real artwork, taking a much more abstract approach to the idea, of course - as you can see above, the real Lahmu was pretty similar to medieval woodwose or contemporary bigfoot and yeti in appearance. However, I think the design nonetheless does its job and, quite importantly, doesn’t look out of place next to associated figures designed earlier by Kaneko: Tiamat (probably the only depiction which tries to follow the completely bonkers descriptions in Enuma Elish instead of succumbing to the DnD influence and incorrectly reinventing Tiamat as a dragon - major improvement over the boring SMT II design), Apsu and Mushussu. I do have an issue with the compendium asserting Lahmu was depicted as a snake though, as that wasn’t a thing at any point in time.

While I have nothing but praise for the design itself out of context, and would actually love to see it used as a generic demon in future games, that’s where the good ends. The writing completely fails at capturing what Lahmu actually is. Frankly, the very idea of making Lahmu a major player in a story feels rather thoughtless - imagine trying to do the same with kikimora or something along these lines.. It doesn’t help that there is no shortage of major Mesopotamian figures with no megaten presence.

It’s also rather weird that the game seems to portray Lahmu as a unique specimen, since in Mesopotamian myths this name refers to a category of beings, not to an individual, with some very rare exceptions I’ll discuss later.

Lahmu isn’t exactly major by any means, but it’s nonetheless pretty easy to judge accuracy in this case. Excavations have provided us with quite literally heaps of evidence, making it rather clear what this bizarre hairy entity meant to people who first came up with it. How come? Rather than to the world of gods, lahmu belonged to that of apotropaic and household spirits - more a Mesopotamian answer to zashiki-warashi or domovoi than something comparable to major gods of classical mythology. Mesopotamian sources generally avoid associating lahmu with both the textual symbol of divinity, the so-called “divine determinative” or dingir, which preceded names of gods in texts, and with its pictorial equivalent, horned headdress.

As an apotropaic creature, Lahmu was not perceived as malevolent, but rather as a protector of the household, keeping it safe (through violence, if necessary) from beings less favorable towards mankind. The role of many other fantastic creatures was understood similarly - kusarikku (bull man), mushussu (lion-dragon) and many others were frequently invoked to protect houses, and figurines of them were found buried under doorsteps in many ancient settlements. In addition to keeping evil away, they were also meant to invite good into the house.

Lahmu are generally kept apart from the categories of malevolent beings (utukku lemnutu), though it is possible in some cases they were imagined as former enemies of major gods who repented and entered their service. In art lahmus sometimes also fight each other, but the meaning of this motif is unknown and doesn’t necessarily represent combat between good and evil, as summarized by Frans Wiggermann, an Assyriologist who wrote the most extensive source to date on the topic of Mesopotamian apotropaic creatures:

A slightly different, non-standard take on Lahmu can be found in two sources: Enuma Elish, the 1st millenium “epic of creation” (just one of many - hardly some grand central scripture of ancient Mesopotamia) and so-called “Anu theogony,” a list of ancestors of the sky god Anu present in some of the god lists compiled by ancient scribes, including the famous An-Anum. There the name refers to a singular being, paired with an artificially created (ie. not based on preexisting beliefs) feminine equivalent not attested elsewhere, Lahamu. Contrary to what the V compendium claims, Lahamu does not appear alongside Lahmu otherwise - the only apotropaic beings commonly appearing as a male-female pair are the scorpion people.

However, even with the above taken into account, the characterization in V doesn’t reflect the myths: this “ancestral” Lahmu is likewise portrayed as benign in the Enuma Elish, not as a vanquished evil god. Indeed, he lines up with other decidedly not malevolent deities, including the usual heads of the pantheon, to praise Marduk after his victory. Additionally, it’s hard to imagine this tradition was particularly influential, as even in the Enuma Elish itself the regular Lahmu still makes an appearance, listed among various supernatural beings given a new backstory as Tiamat’s creations, alongside other usual suspects like mushussu, kusarikku, scorpion men and so on.

What inspired the SMT V take on Lahmu, then? I personally have no clue, beyond being able to say with certainty that it had very little to do with Mesopotamia. A friend made a convincing case that we’re simply looking at the work of writers whose frame of reference aren’t actual primary sources or even just “occult” books, but the isekai genre. It would certainly explain the baffling use of the name for a completely generic “ancient demon lord” entity. It’s not even the authentic Lahmu wouldn’t work as part of Sahori’s arc, arguably it would strengthen it and give her more character without what in my opinion constituted a pretty lame copout.

Speaking of sources: it needs to be stressed that it seems Doi’s only point of reference (based on almost word by word quotes in the design commentary), as well as seemingly the only source used as basis of the compendium entry, is the Japanese wikipedia article about Lahmu, which is, to put it very lightly, not great, and relies on sources which were already outdated before WWII, which formerly dominated the English one too. Many wikipedia editors have a weird love of resources which were discarded by most people 50 years or so ago no matter how many credible journals and monographs presenting the modern consensus and research which lead us here can be accessed freely.

Of course, it generally does not seem like the staff of SMT V cares much about Mesopotamian mythology, judging from the contents of the Cleopatra dlc which just declares Mesopotamian gods were damned en masse (why is that in a dlc and no mention of it is made during the Ishtar boss fight is beyond me). Presumably Enlil and friends were not cool enough for Bethel, which seems to roughly be “every mythology normies know in one place,” a far cry from the composition of organizations in past Megaten games which usually mixed the famous with the obscure in unexpected ways (Soul Hackers’ combination of the well known biblical narrative about fallen angels and Algonquin folklore comes to mind as one example). There is also this absolute horror which I will leave without comment:

Well, at least she is not here to be presented as a corrupting influence on little girls this time, I guess.

Surely they fared better when it comes to less ancient and less obscure myths, right? No way for a Japanese studio to mess up adapting the classics of Japanese mythology like Kojiki and Nihon Shoki? Well…

Tsukuyomi and Amaterasu

Perhaps the inclusion of Amaterasu in this entry is somewhat surprising at first glance. “Antonia,” you might ask, “why is she here considering she is not in V at all?” Technically that is right. That’s actually the problem, though. The game essentially writes her out, and then turns Tsukuyomi into a bootleg Amaterasu for no good reason.

V heavily depends on the concept of Amatsukami and Kunitsukami, rooted in two classical works of Japanese semi-mythical historiography, the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, completed respectively in 712 and 720. In theory, the distinction seems clear - Amatsukami live in heaven and Kunitsukami on earth, as expected based on the meaning of these terms - but in reality the use of them was often ambiguous in religious practice and legal documents. For example, in Ryō no gige, a legal commentary composed during the reign of emperor Junnin, the distinction is simply based on the location of the shrines dedicated to specific deities.

An argument can also be made that it was hardly the central concern of both clergy and laypeople throughout much of Japanese history. In sources from between the 11th and 16th century - the time commonly referred to as Japan’s “medieval” period in western literature - kami are usually instead classified based on their placement within syncretic Buddhist networks:

as representations of some primal form of enlightenment

as secondarily enlightened through own salvationist effort

as unenlightened, and in some cases hostile to Buddhist teachings

These categories tend to be described with limited, if any, concern for distinction between amatsu and kunitsu; for example, the Ise (Amaterasu) and Suwa (Suwa Myojin = Takeminakata, kunitsukami par excellence) shrines both held their enshrined gods to be examples of the same category of deities. Of course, classification varied between shrines too, and even parts of a single temple complex could have divergent views on classification of the same deities.

Putting this digression aside - the concept of Amatsukami is heavily tied to Amaterasu in the specific mythical texts SMT generally draws from when it comes to depicting Shinto deities, and the only other contenders are various poorly defined primordial entities, for simplicity often omitted in adaptations.

As a result, members of the Amatsu race are all demons tied to narratives pertaining to Amaterasu, the only exception being Hinokagutsuchi (not pictured below).

Omoikane coordinates other deities while Amaterasu hides in the cave, and later serves as her advisor in other situations.

Tajikarao seals the cave to prevent Amaterasu from hiding inside ever again.

Takemikazuchi is one of the deities sent to pacify the earth in Amaterasu’s name in the Kojiki; in the Nihon Shoki he instead insists on joining Futsunushi, appointed to fulfill a similar role.

Ame no Uzume (moved to the Amatsu race in IV) rather famously performs a song, dance and striptease montage to lure Amaterasu out of hiding.

Ame no Torifune is one of the names for a nebulous “boat-god” appearing in two myths: once when Hiruko is abandoned by his parents, and, in varying roles, in the land transfer narrative. In the Kojiki, Ame no Torifune assists (transports?) Takemikazuchi due to his journey to earth.

Additionally, a number of deities who are according to myths classified as Amatsukami are included in other races, but are identified as such in quests:

Ame no Futotama (added in Soul Hackers, which didn’t have the Amatsu race in it; consistently in the Enigma race), who performs various rituals meant to make the effort to lure Amaterasu out of hiding successful. In Kogo Shui, a chronicle of the Inbe clan composed in the early 800s, he is presented as the principal force responsible for ending her self-imposed exile, at the expense of other deities such as Ishikoridome (the tutelary deity of mirror makers), probably because the intent of the chronicler was to restore the high status of his family. In Strange Journey he appears as Uzume’s wingman one of the gods seeking to bring Amaterasu back home. He explicitly identifies himself as an Amatsu in IV, where he likewise appears in connection with Amaterasu.

Futsunushi (normally part of the Kishin race, in V - Wargod) - true to myths, V explicitly has him call himself an Amatsukami. In the Nihon Shoki land transfer myth he acts more or less as enforcer of the will of the amatsukami figureheads, that being the primordial deity Takamimusubi and Amaterasu, but not Tsukuyomi; somehow it is not much of a problem to him in his side quest that Amaterasu is nowhere to be found and a guy she is, as you’ll soon see, not very fond of, is bossing everyone around…

Amaterasu’s rule over the heavenly gods is established when either Izanagi alone or Izanami and Izanagi as a pair after her birth. Two aspects of the myth vary: whether the children are born the expected way or created by a supernatural act of Izanagi alone, and what areas are assigned to them to rule. In one version Tsukuyomi rules the “sea plain” and Susano-o the earth (or rather - is meant to rule it, since he instead engages in the usual Susano-o antics and refuses to do his job); in another Tsukuyomi rules a nondescript land of the night (in kokugaku commentaries from the 19th and early 20th century sometimes identified with the “land of Tokoyo” which many readers of my blog likely know from the story of the “bug of Tokoyo” and Hata no Kawakatsu) and Susano-o - the sea plain. Finally, in yet another Nihon Shoki passage Tsukuyomi is sent to the heavens alongside Amaterasu - a role which however seems to be temporary, as you’ll see very soon.

While it technically makes sense to group Tsukuyomi with the Amatsukami, since he is indeed a god residing in the same location in at least one version (for a time), it’s important to stress that in religious worship he generally lacks a strong connection to Amaterasu. At Ise, where her main shrine is located, and in relevant religious literature, she is associated first and foremost with Toyouke, a deity connected to food production whose gender seems to vary between sources. Tsukuyomi technically has a minor shrine nearby, but in at least one text from Kamakura period Ise its divine inhabitant is instead said to be one of three obscure “magistrates” serving Amaterasu (Suikan, Chikan and Tenkan). On top of that, Amaterasu and Toyouke were collectively referred to as the sun and the moon in some documents, an association based on their connection to the diamond realm and womb realm mandalas.

In myths Tsukuyomi is very rarely a dramatis persona, generally speaking. In the Nihon Shoki, aside from a number of accounts of his birth (inevitably side by side with his more notable siblings) and a handful of references to legendary or historical events involving humans performing Tsukuyomi-related oracles he basically only appears in one myth… in which he gets banished from heaven for murder. The story is neither particularly detailed nor a part of any longer cycle unlike that of conflict between Amaterasu and Susano-o.

The premise is fairly straightforward: Amaterasu sends Tsukuyomi as her representative to visit Ukemochi, a goddess of food. Ukemochi prepares a banquet for her guest by producing various consumables from her… bodily orifices. Tsukuyomi is profoundly disgusted by this and in a fit of rage kills her for this affront to his dignity. He then ascends back to heaven and tells Amaterasu what he did; in a fit of (arguably more justified) rage she banishes him for it and, presumably, lives happily ever after.

This myth is most likely meant to serve as an explanation for separation of night and day. I’ve noticed that a number of secondary popular sources in English claim Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi are spouses in this narrative, but so far I found no support for this claim - in both Kojiki and Nihon Shoki Amaterasu is pretty firmly unmarried, and I have yet to see any later myth where she would be associated with Tsukuyomi. At least one source from among the medieval Ise documents appears to indicate carnal relations occurred between Amaterasu and Toyouke (in this context male), though.

It’s worth pointing out that at no point in either the Kojiki version or the multiple accounts listed in the Nihon Shoki does Tsukuyomi interact with Susano-o - conflict with him is entirely Amaterasu’s domain. In syncretic documents from Ise an additional cosmological dimension was added to it by making Amaterasu represent “Buddha nature” and enlightenment, and Susano-o the opposition to it. In V, though, the only conflict even just alluded to is between Tsukuyomi and Susano-o if you opt not to side with the former’s human guise.

Not much material on Tsukuyomi can be found elsewhere, and especially not anything that would justify placing him in the position you’d expect his sister in, like in the case above. He’s briefly mentioned in the poetry collection Man'yōshū in relation to a potion of longevity - which to me seems like an echo of Chinese mythical motifs related to the moon, especially those related to Chang’e, but don’t quote me on that (chronologically it definitely would make sense, as Chang’e was already well established some 800 years prior to first attestation of Tsukuyomi). Famous narratives pertaining to the moon like Tale of the Bamboo Cutter or Hagoromo do not even allude to him. In terms of honji suijaku material, all I could find is a single instance of equation with one of the wisdom kings, in this context a minor satellite deity in a ritual.

A theory which I personally think can be discarded on the account of its author being a Jungian psychoanalyst rather than historian is that of Hayao Kawai, who argued that Tsukuyomi was actually equally significant and purposely left somewhat featureless, so that struggles between opposing principles can revolve around him. The fact that he appears in no myths about conflicts between Amaterasu and Susano-o and that his only myth portrays him as rather violent feels like a considerable setback, but as we can learn from his article The Hollow Center in the Mythology of Kojiki he seems to have a kokugaku-like bias. He asserted that Kojiki matters more. According to him Nihon Shoki was a “political” work while Kojiki - simply some primal manifestation of truly Japanese spirit not bound by such trivial matters as “historical context.”

Note both works were composed by a similar cadre of people at around the same time, and that Nihon Shoki is the one which usually lists multiple versions of each event, even if they’re contradictory, which by the standards of 8th century royal propaganda - which both of these books ultimately are - seems much closer to unbiased to me.To sum up, unless I’m missing something, Tsukuyomi only received a boost in prominence in popular imagination due to modern popculture. I don’t exactly think Naruto and other similar media should serve as a point of reference for such matters, and as a result I see little reason to refer to him as prominent and even less for overlooking Amaterasu in favor of him. II recognized that:

In contrast with Tsukuyomi’s general irrelevance, it should be noted that non-Kojiki non-Shoki material concerned with Amaterasu recasts her (or, in some cases, him, it can get complicated) in a variety of major cosmogonic roles (often arguably giving her more personal agency than she has in many Kojiki and Shoki passages): as a creator deity equated with Brahma (Bonten; Amaterasu effectively displaces own parents from their Kojiki/Shoki role which is rather funny), as a judge of the dead associated with king Enma and Taizan Fukun, as an opponent of Mara (unlike the Buddha, she seemingly opts to strike a deal with him), and more. She has no shortage of rarely discussed myths, many of which, by the virtue of combining elements from Shinto with Buddhism, Taoism and even Hinduism feel very suitable for the syncretic settings of Megaten games.

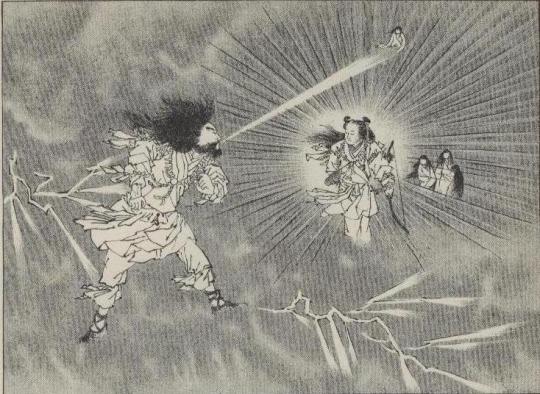

Disguised Amaterasu confronting Susano-o (public domain)

Even assuming the decision to use Tsukuyomi over Amaterasu was tied to the idea to make the deity’s alter ego the Japanese prime minister, the entire idea feels hard to justify. Let’s even assume that a female prime minister would be too much of a suspension of disbelief (unlike, you know, gods, angels and horrid tokusatsu characters) - it still would be easy enough to declare he’s actually Amaterasu in disguise, seeing how even in the Kojiki/Shoki alone she does that on occasion, namely when she plans to confront Susano-o after hearing he’s heading to her domain. The fact she’s female in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki (and in many other sources) didn’t really stop Amaterasu from appearing as a seemingly male figure, either. She is no stranger to being equated with male figures in syncretic context, including Dainichi (Vairocana), Aizen Myo-o (one of the wisdom kings, connected to lust), and even king Enma. It has even been proposed that the easily recognizable modern image of Amaterasu as a maiden in white robes is partially derived from that of distinctly male Uho Douji, one of her Buddhist alter egos.

I find it peculiar that not just Tsukuyomi but also every single other figure you’d expect to feel the need to mention Amaterasu just… doesn’t. Futsunushi and Yatagarasu do not, neither does any of the kunitsukami. Perhaps the writers felt insecure about their weird dream prime minister/toku reject (I actually do not think Doi’s “toku” designs are good toku designs but that’s another matter) original character to such a degree that they worried the mere mention of Amaterasu would be too much for him not to fall apart in the eyes of the players? Hard to think of a sensible rationale. Until proven otherwise I see no reason to entertain the possibility that Tao is Amaterasu, also, as this identification is not made - or even alluded to - in the game, and her unique race name, Panagia, is related to Mary (especially in the Eastern Orthodox Church).

The case of Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi seems to be a part of a bigger pattern in V - whenever possible, female mythical figures are sidelined. Vasuki being Shiva’s main supporter even though Parvati is right here is another example. I’d personally count the Melchizedek quest too, as it basically reassigns Anat’s mythical role to the archangels for the sake of… a shallow Nocturne reference, I guess? One which doesn’t even work too well because Baal Avatar in Nocturne worked only in the context of this specific story and has precisely 0 reuse potential.

As a side note, since I’ve already mentioned one of the quests pertaining to him - Baal once again does not fare well in general, ultimately serving as an antagonist for Demeter, which on an unintended meta level feels like the conflict between what made Megaten a truly unique and remarkable franchise and its current direction. As usual, he gets to exist to hype up fan favorite Beelzebub for no real reason.

While Kaneko’s design will likely forever remain one of the greatest and most accurate depictions more recent than the late bronze age, it seems like Baal’s character will remain detached from it. Which is a shame because Megaten could basically pull off a Baal cycle side quest at this point, considering a large chunk of the cast already appears in the series.

I think IV actually came pretty close to doing something interesting with Baal for once by having him pose as Gozu Tenno, the most major of Susano-o’s Buddhist associates and/or alter egos, but ultimately that premise was wasted on more Beelzebub instead, rather than on a fun exercise in comparative mythology. If you ask me it would make for a better twist in that quest to have Susano-o in it than Beelzebub, but alas.

Luckily, V has Susano-o in a major role! Surely that resulted in something worthwhile, right?

Susano-o Aogami

Tragically Susano-o himself fares no better than his siblings in this game. Donning what seems like the combo of a bodysuit and a tailcoat, he provides the player with rather characterless advice through the game. The identity of the baffling “metal man” teased months ago had been a subject of much debate, with proposals as varied as the Demi-fiend, Indra (not to be confused with Indrajit!) and Marduk all coming up in fan theories I can remember off the top of my head. Susano-o seemed like an improbable option since he, after all, already has a popular, well established design. Sadly that was not enough to spare him.

The design, to put it lightly, doesn’t go well with either of Kaneko’s Susano-os, who do go pretty well with each other. So well that I wonder if the idea was to simply depict Susano-o at two different points in his career, especially since the peculiar motif on Devil Summoner/Soul Hackers Susano-o reminds me of his connection to the mysterious “land of roots,” Ne no Kuni, known for example from the myth where Okuninushi has to confront him in order to marry his daughter. While Kaneko based his Susano-o on traditional portrayals and on a variety of famous artifacts, such as haniwa figures depicting the everyday clothing of Kofun period Japan and the famous seven-branched sword (with one extra branch added), Aogami just looks like he’s wearing a spandex bodysuit covered in broken glass.

The game waves off any inconsistency by declaring that Aogami is actually a robot clone with Susano-o’s essence, but it barely amounts to anything and much of the info (which... still doesn’t explain much, to be honest) is locked behind a paid dlc, specifically the Mephisto one. And even then, this weird decision is hard to justify, and the dialogue doesn’t really seem to deny that Aogami is meant to be the genuine article, judging from, for example, Tsukuyomi referring to him as brother. Neither feels like mentioning Amaterasu even though both of them are defined more by relation to her than to each other, of course.

What makes Aogami particularly annoying is the fact that in myths Susano-o’s character is pretty well defined, and remains notably consistent between the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki and other sources. It’s described in rather striking terms: “This god’s character was evil, and he often took pleasure in weeping and rage. Many people in the country died. Green mountains withered,” declares a section of the Shoki. His deeds are described as “filthy and wicked” elsewhere, as noted here. He is held as the archetypal example of an “araburugami,” a wild, raging god.

His reputation is largely tied to the myth about his conflict with his sister Amaterasu. After a trial by pledge determines he can enter heaven, he commits a series of morally reprehensible acts, which slightly vary between versions, but generally involve messing up the heavenly fields, flinging his feces around, releasing the heavenly horses and so on. Amaterasu initially lets it be, but eventually reaches a breaking point and hides in the cave, plunging the world into darkness.

What causes this also differs between versions, but generally is assumed to be connected to Susano-o killing and skinning one of the heavenly horses and throwing the carcass into Amaterasu’s room, either wounding her or killing an otherwise unknown servant. In a variant of the Nihon Shoki narrative she instead decides that the point of no return is Susano-o defecating in her room. Either way, the blame is on him and him alone for temporarily depriving the world of light.

Various passages related to the aforementioned myths highlight Susano-o’s impetuous, raging nature. Poor anger management seems to run in the family, considering the already discussed myth about Tsukuyomi. It’s worth noting that in the Kojiki a very similar myth presenting Susano-o as the killer is included, though the food goddess is named Ogetsuhime instead. However, prior to the dawn of the kokugaku style of scholarship in the Edo period, which favored the Kojiki at the expense of other sources, I think it’s safe to say Nihon Shoki can be assumed to be the more widely known variant, and allusions to it are known from Heian period poetry.

The other famous myth of Susano-o is the slaying of Yamata no Orochi, the eight-headed serpent, and saving the life of Kushinada-hime. While the hydra (a great design and pretty fun fight) is pretty clearly meant to be a stand-in for Orochi, Kushinada at no point in time comes up despite being in the game.

A humorous print showing Susano-o and Kushinada-hime selling grilled cuts of Orochi meat, from the collection Ukiyo-e Ōta Memorial Museum of Art

A friend noted that Aogami is essentially what a Hollywood adaptation of Japanese mythology would be like, and I can’t really disagree with this point. His design even resembles the absolutely atrocious cgi bodysuits present in every single one of the interchangeable superhero movies.

An additional sub-problem with the treatment of Susano-o in the game is Amanozako.

Amanozako as depicted by Toriyama Sekien, Shigeru Mizuki and Masayuki Doi

She is a somewhat obscure yokai known chiefly for her inclusion in one of Toriyama Sekien’s famous “night parades,” where she is depicted as a hideous, enormous hag, true to her description from the Edo period encyclopedia Wakan Sansai Zue. As we can learn from these sources, she was believed to be a daughter of Susano-o created when he released the accumulated fierceness from his body. Another Edo period author, a certain monk named Myōryū, adds that she was the ancestor of tengu, though this is not mentioned anywhere else (granted, it’s not like Amanozako is, she is, as far as I can tell, an invention of Edo period authors) and generally speaking contradicts the common Buddhist view of tengu as people reincarnated in the realm of makai or tengudo for spreading improper teachings. It is however undeniable that Sekien’s portrayal takes many visual cues from the common image of long-nose tengu. Sekien’s portrayal in turn heavily inspired Shigeru Mizuki, the artist responsible for the modern concept of yokai, as you can see above.

In V, Amanozako is instead a little girl. She doesn’t even have a tengu nose. The less said about her character, the better, but she is hardly a ferocious boogeyman and I am frankly unsure what motivated her creators. Given how much of her dialogue is like I am not sure if it’s a topic I want to explore further, so I will just say that to put it very lightly I am not a fan of the liberties taken at all. I would be uncomfortable with the dialogue even if it belonged to a character who actually fits the “little girl” role, truth to be told.

I should note some criticisms miss the mark too. Some people seem to speak of the original with some weird reverence worthy of the infamous Woman’s Encyclopedia, treating hear as a powerful independent mother figure or something along these lines. This is wrong too. She's essentially someone’s oc boogeyman with two or three more or less tangible sources behind her. You don't need to make her into some grand example of transcendent "divine feminine" (a term which is generally an instant red flag in mythology discussion) to highlight that she shouldn't be what she is in V. Simply put, I believe women should be allowed to be one note boogeymen largely born from the sense of humor of Edo period night parade scrolls artists.

Both Aogami and Amanozako, and to a degree Lahmu as well, seem to be part of a bigger trend in V, though not the same one as replacing Amaterasu with Tsukuyomi. It’s becoming rather obvious that the current staff behind the games seems to believe that turning the character of depicted figures upside down is what suits the series well. Examples of such changes include:

Dagda (IVA): from a fun-loving, fatherly god to skeletal nihilist

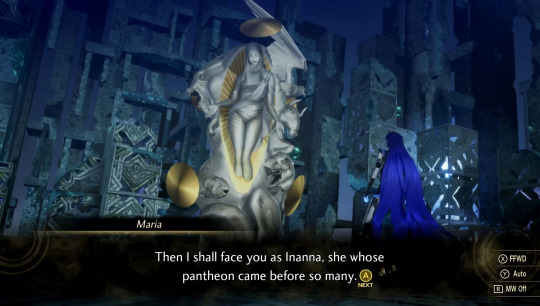

Inanna (IVA): I covered this matter in an earlier post extensively; from a pretty firmly childless goddess generally connected to the joyful aspects of sexual and romantic love (and to a plethora of other things, like war and royal power) to a pregnancy monster.

Demeter (SJR): arguably the worst one still, next to Inanna. From the archetypal mother to a ditzy little girl (“little rascal” as one of the devs put it himself, I believe). By the way, she talks with Zeus in V. Guess if Persephone comes up at all.

Susano-o (V): as discussed above: from a rebellious, very emotional and sort of unpleasant god to a stoic noble mentor figure.

Amanozako (V): from a monstrous hag to another little girl.

Lahmu (V): from a generally benevolent house spirit to a wicked demon lord.

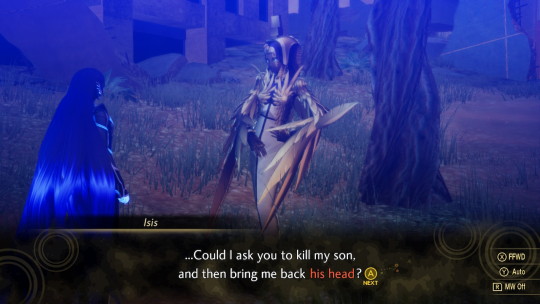

Sadly, in V this seemingly started to spread to how preexisting Kaneko demons are written too. A particularly sad case seen above is Isis, a figure normally defined by the love for her family. I must admit this annoys me for more than one reason:

she is a major figure with a lot of source material to use, much of this material being focused on her efforts to save (or elevate) Horus against all odds, even if it results in conflict with other major deities like Ra

she is one of the best examples of what makes Kaneko’s art work uniquely well, the perfect blend of a high fashion influence with reverence for the classical image known from ancient art

in IV she instead appeared in a great quest adapting the source material pretty well

it feels like this happens only to make room for a Doi demon (Khonsu)

In a way this is actually more egregious than something bad in every possible way at once, like Aogami, who to me seems impossible to salvage, unlike Isis, who is basically a problem only because the V writers went out of their way to make sure she’s “subverting expectations” or whatever goal their had in mind. It’s hardly the most notable example of wasted potential in the game, though. That title belongs to…

Nuwa

I saved Nuwa for last, as I figured it would be thematically appropriate to both start and end the part of the article dedicated to specific demons with ones I was actually genuinely excited for prior to actually learning about their full role in the game. While to put it lightly I am not enthusiastic about how she turned out in the game, I think she has one advantage many other new plot-relevant demons lack, namely a perfectly salvageable design.

Nuwa is a cosmological figure attested in Chinese sources at least from the beginning of the reign of the Han dynasty (c. 200 BCE), and still reasonably famous today, even just judging from the amount of retellings of her myths aimed at kids I was able to find. Her exact role varies depending on time period, location etc., but the core remains about the same: she creates humans, often out of clay, and in a separate myth repairs the damaged pillar of heaven, saving mankind from various cataclysms in the process.

The human creation myth has been at times used to justify social stratification, and many sources state that humans were not created equal by her - while she initially sculpted them carefully by hand from clay, she eventually switched to simply spilling mud with a rope. The first batch of humans were the rulers and nobles, these made from spilled mud became peasants. Another variant attributes the creation of humans to Nuwa feeling lonely.

While to a western viewer Nuwa might seem like a Prometheus-like figure at first glance, I find it important to stress that she is not really portrayed as a rebel against authority in any myths.

Nuwa portrayals from various periods of history

Nuwa is commonly associated with snakes, and as you can see above many works of art, both historical and modern, depict her with some serpentine characteristics. However, their extent varies, and there are completely human depictions too (contrary to what Doi says). The pictures above are just a small sample, covering everything from the Han dynasty (the first two reliefs) to the present (the final two statues). I’m therefore not particularly bothered with keeping her form more or less human, even though I personally like the oldest version here the most.

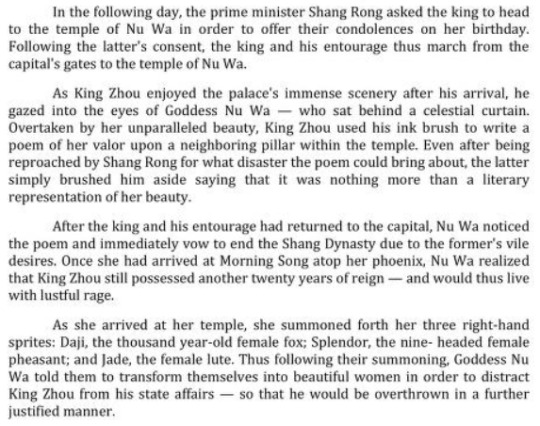

Unlike a number of other people online critical of V I also have no major issue with her outfit, it’s not really much more explicit than Kaneko’s Kikurihime and the like, ultimately, which are fine by me (I do think Kaneko was better at picking which demons to make “sexy” and at drawing attractive people than Doi is but this is another matter). I do think Doi’s trademark tip toes pose is pretty dumb, though, and there are scenes which feel like very awkward fanservice, particularly near the end of the game. I do not think “sexy Nuwa” is a fundamentally inappropriate idea given the fact that it is more or less what we learn from the classic Chinese novel Investiture of the Gods (I do not think Doi or anyone else at modern Atlus is familiar with it, though):

I also quite like her second form (Doi’s horror vacui tendencies notwithstanding) and find her unique skill to be one of the few genuinely fun ones in the game. It evokes imagery known from the myth - she even has a rope - and isn’t quite as annoyingly over the top as, say, Idun’s unnecessarily long animation. I think only Tandava is a cooler, more appropriate unique move.

That’s where the good ends, though. Past her introduction - which I do have to admit is rather great, and it was a good idea to highlight it in trailers since it’s one of the few actually striking sequences in the game - Nuwa’s character is basically nonexistent. In terms of depth and complexity she’s somewhere between a heroine from the original DDS novels and Pascal, and I’m under the impression in 90% of her scenes you could pretty easily swap her for Hayataro. More on that later, though.

Initially I wasn’t bothered by what seemed to be an absence of Fuxi. The association between them is actually hardly universal in primary sources. They are siblings and/or spouses at times, but it is also fairly common for Nuwa to be depicted as a solo act, and there are references to association with the Chinese “flood hero,” Yu the Great, in a number of texts too. On top of that in one account her helper in the creation of humans is Huang Di, tasked with sculpting internal organs. In Investiture of the Gods Fuxi if my memory serves me well isn’t even mentioned, and Nuwa largely interacts just with her femme fatale minions. Additionally in some locations she is associated with the Jade Emperor, appearing as one of his daughters.

It was only the fact that Nuwa is basically stripped of context in the game that made me annoyed about the complete absence of Fuxi, since the result feels like an attempt at disconnecting her from her place of origin more than anything. Unlike the Bethel reps, Nuwa never mentions where she is from. She doesn’t allude to any figures from myths related to her either, and doesn’t interact with other Chinese demons (note that they had no problem with having Shiva, Odin and Zeus do that). A peculiar omission which makes me wonder to what degree she dodged the sort of completely awful characterization Xi Wangmu got in IV only by being basically void of context.

I am tempted to compare Nuwa to Taotie in Raidou 2 as far as Chinese demons go - while he is ultimately not that major, he’s handled considerably better, gets to boast about his myths and all around feels like an actual character. I’m a huge fan overall:

Also, I love his dumb running animation.

Back to Nuwa, I think her problems stem from a few interconnected sources.

To begin with, it’s painfully clear she doesn’t exist to be an independent character, let alone a character representing some 2200 years worth of material. She exists to act as Yakumo’s pet. Imagine if Mastema was treated like that in Strange Journey...

She only ever brings up creating humans twice, and makes no other references to her mythical role. She even barely talks about being a deity. Truth to be told, she hardly talks about anything other than Yakumo. I think this is to a degree a byproduct of this game’s treatment of female characters in general, both human and supernatural ones. While I’m not a huge fan of early SMT heroines, let alone the yet older ones, I think the later games have a wide variety of solid female characters, with Rei, Yuko and Zelenin being my favorites (though even minor characters could be great, Naomi from SH only appears in a brief vision quest but leaves quite the impression, for instance). Can’t say that about V. Nuwa isn’t even the worst offender in that regard, frankly. However, human characters are beyond the scope of this article.

I thought that maybe it will turn out that her Bethel hatred (which feels more than justified tbh but the game never really goes particularly deep into this) would lead to some speech about her thinking other gods betrayed their purpose by serving said organization but instead it all boils down to "that's what Shohei wanted :)" and the true ending arguably makes it even worse. Am I supposed to assume she's a self hating nihilist or did the scenario writers forget halfway through she's meant to be a deity too? Why doesn’t she feel anything about presumably erasing every god connected to her, also? Do Fuxi, Yu or the Jade Emperor not exist in this setting?

As a side note, I personally can’t stand Yakumo. Neutral is generally not an alignment I’m a huge fan of, but I think Strange Journey did pretty well in that regard. Commander Gore feels like a good character to compare Yakumo to since both are presumably meant to represent humanity as its peak - but while Gore makes a variety of profound statements and is depicted as a paragon of virtue respected by his crew, Yakumo seems to be a sociopath who proudly calls other people “parasites.” His views also aren’t really challenged anywhere in the game (granted, neither are Tsukuyomi’s! Alignments are handled pretty poorly in this game overall). They kind of seem to clash with Nuwa’s, but it’s not like Nuwa matters, so the game does not address that. Nuwa just affirms over and over again he’s totally great.

Yakumo and other comparably exciting characters

People compared him to Raidou and to Yasunori Kato before the game’s release, but I think ultimately zombie cop and that guy from Devil Summoner who turns into Kumbhanda are a better match.

Another thing which makes Nuwa sound nihilistic and makes her hard for me to enjoy is this line:

A recurring theme of V is that demons hate their forms. Including Kaneko demons designed to match how they were imagined by people who actually believed in them, like Baal. Nuwa is probably the worst example, since only she makes so few references to who she actually is, and only she is obsessed with her Nahobino pair to such a degree. Zeus, for instance, doesn’t seem to care much than his is dead since he can wait for a new one to be born.

However, due to how V setting works, this problem actually implicitly applies to all demons in the game. And this is what I will use to sum up its approach to mythology.

Conclusions: the concept of Nahobino and the future of mythology in Megaten

This post is ultimately redundant because contrary to traditions of the franchise, mythology does not actually matter in SMT V.

All that matters is the concept of Nahobino, responsible for some of the series’ arguably least coherent, least fitting and least fun to draw designs yet, as seen above.

Nahobino, and all associated worldbuilding, have a very simple purpose: strip demons out of context. Their forms depicted in the series do not really matter, neither does their cultural context. Every time a plot-relevant demon is on screen they remind you of that: all they desire is to be able to become a horror vacui monstrosity.

Long ago Kazuma Kaneko said that “the most important aspect when drawing demons is to study their creators.” It is undeniable that in the past that was the idea behind the series. While it wasn’t always successful at it (for example due to reliance on rather dubious sources), and sometimes odd liberties were taken, it is hard to deny that it still came from a love for mythology.

I do not think this can be said about V, though. Quite the opposite, I think it’s a game which wishes it didn’t have to use mythology at all, moving one step ahead of IVA and SJR, where it felt like the core idea is tiresome subversion alone. Now even that feels secondary, even though the new game still has many examples of it.

I think it’s safe to say the age of myth in Megaten is ending. It will continue to feature enemies and summons bearing names certainly lifted from mythology, but I find it unlikely that it will go back to genuinely caring about it.

Bibliography

Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts by F. Wiggermann

Exit Talim! by F. Wiggermann (partially outdated due to Wiggermann’s own research from MPS)

Nihon Shoki

Encyclopedia of Shinto

Rewriting the Past: Reception and Commentary of Nihon shoki, Japan’s First Official History by M. A. J. Felt

Re-positioning the Gods: "Medieval Shintō" and the Origins of Non-Buddhist Discourses on the Kami by F. Rambelli

Duality and the Kami: The Ritual Iconography and Visual Constructions of Medieval Shintō by L. Dolce

Outcasts, Emperorship, and Dragon Cults in The Tale of the Heike by B. T. Bialock

Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3: Rage and Ravage (extract) by B. Faure

Transcending Locality, Creating Identity: Shinra Myojin, a Korean Deity in Japan by S. J. Kim

The Flood Myths of Early China by M. E. Lewis

Nü Wa by U. Theobald

244 notes

·

View notes