#Wet Media Acetate

Text

Cover Spread Illustration for Going Down Swinging Edition 43: Hell & High Water 🌊🔥

Been a while since I’ve been able to do a traditional multi-layer acetate illo for a gig, so I was stoked to pick up my POSCAs for this 🖍

GDS Edition 43 Launch Event is on 22 Sep at The Mission to Seafarers down in Naarm/Melbourne ! Event deets on FB 🗓

Special Thanks to GDS Editor Hollen Singleton as always for having me ❤️🔥

[ID: A graphic illustration of yellow and blue flames rising out of pink waves]

#Illustration#Drawing#Art#Editorial Illustration#Magazine Cover#POSCA#POSCA Markers#Acetate#Wet Media Acetate#Traditional

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grafix Dura-Lar 004” Film Coated to Accept Water Based Mediums, Perfect for Watercolor, Planning Compositions, Painting Surfaces or Printmaking, 50" x 12 Feet, Wet Media

Grafix Dura-Lar 004” Film Coated to Accept Water Based Mediums, Perfect for Watercolor, Planning Compositions, Painting Surfaces or Printmaking, 50″ x 12 Feet, Wet Media

Price: (as of – Details)

Grafix .004” Wet Media Dura-Lar Film is designed to give you the best features of both Mylar and Acetate. This durable film is treated on both sides to accept water-based mediums, markers, and ink. It wipes clean with a damp cloth, so it can be used again and again! Use it to plan your next painting, or as a painting surface itself. Like the other types of Dura-Lar, this…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

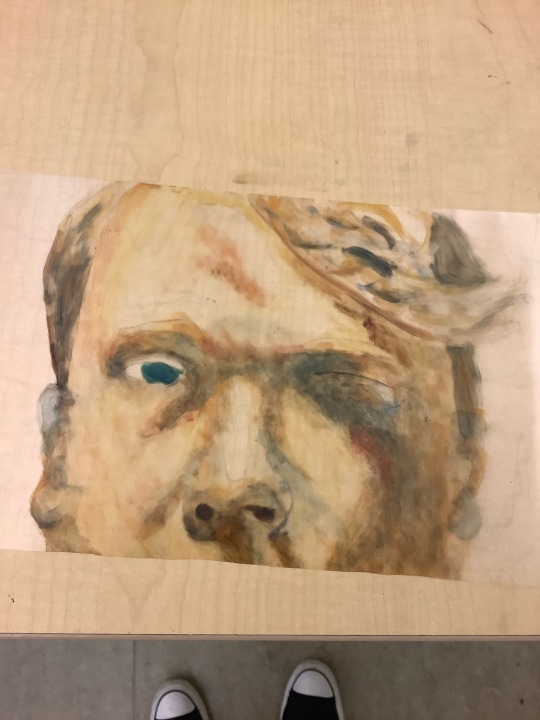

For this week I have gotten my first full painting on the wet media acetate. I am pleased with the colors and mixture of color while trying to keep it clear. It is very interesting to look at the brush work that I have been doing for this work. Now for the other works I was testing my layering effect and I am scared to see what will happen when there is more layers of organza/ acetate as I add on more layers of these facial disorders.

0 notes

Text

Free Sample Processing

Contact Dave Davidson at [email protected] for details. Parts that can be submitted for sample finishing include: 3D Printed parts (both metal and plastics), machined components, investment castings, forgings and others. For contract finishing information SEE: https://dryfinish.wordpress.com/2018/06/15/high-energy-centrifugal-iso-finishing-contract-services-for-deburring-and-super-iso-finishing-information-and-sample-finishing-request-form/

Hands-free and High-speed Finishing and Polishing of Additive Manufactured Parts

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Many Additive Manufactured (3D printed) can be finished and polished with this rapid deburring, smoothing and finishing method. Time cycles can be as much as 1/10th that of conventional mass finishing methods. CONTACT: Dave Davidson at [email protected]

Centrifugal Iso-Finishing Equipment

Accelerate and streamline your deburring and finishing operations. This equipment comes in sizes from 12 liters (0.4 cubic foot) to large 330-liter machines (12.8 cubic feet) with 12-inch diameter barrels with 42-inch barrel lengths. Wet and dry media can be used for either aggressive abrasive deburring and smoothing operations or final super-finishing and polishing operations.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

Contract Finishing and Post-Processing Service Bureau

Contact us for Sample Finishing and Processing for your contract finishing needs. RFQ’s and Finishing Estimates can be provided from part prints (subject to processing verification). Processing available includes: Deburring, flash removal from plastics and rubber, surface smoothing, super-isotropic finishing and polishing. CONTACT: Dave Davidson at [email protected]

SEE more video at: https://dryfinish.wordpress.com/2017/02/23/centrifugal-isotropic-finishing-operations-on-precision-parts-video/

youtube

Super Iso-Finishing Precision Components

from all Industries

Industries served include:

• Medical Implants and Devices

• Dental and Orthodontic Parts

• Aerospace Engine Components

• Aerospace Airframe and Structural Components

• Automotive Engine and Powertrain Components (Isotropic Finishing)

• High-Performance Motorsports and Powertrain (Isofinishing)

• Motorcycle engine and powertrain

• Machine Tooling,

• Metal 3D Printed Parts

• Plastic 3D Printed Parts

• Injection Moldings and Machined Plastics

• Springs

• Acrylic and Acetate Polishing

• Precious Jewelry and Fashion Accessory Polishing

• Screw Machine Part Deburring and Super-Finishing

• Eyewear Components

• Firearms and ammunition

• Metal Injection Molded Parts (MIM)

• Investment Castings

• Powdered Metal Parts Smoothing and Polishing

• Deflashing and smoothing of plastics and rubber

• Surface Burnishing for Compressive Stress

How it Works…

Centrifugal Iso-Finishing Technology equipment operation is similar to the operation of a “Ferris Wheel” but this Ferris wheel operates at high rotational speed with the turret swinging the barrels around its periphery while the barrels counter-rotate at high speed. This motion imparts high centrifugal force to the parts and media in the processing chambers and finishing and polishing work is performed ten times faster than conventional low-energy finishing equipment. On many parts, single-digit micro-inch Ra surface finishes can be achieved.

What we do – How to Contact Us

We help manufacturers minimize hand-deburring operations and develop highly polished isotropic surfaces when needed with high-speed and hands-free processing. See my contact information below:

Dave Davidson | Senior Technical Advisor

Deburring/Finishing Technical Group

(T) +1.509-230-6821 – Direct Desk

(M) +1.509.563.9859 (for International calls with WhatsApp)

(E) [email protected]

https://dryfinish.wordpress.com

(A) 458 N. Walnut Street, Colville, WA 99114 USA

Centrifugal Iso-Finishing Technology – High-speed and Hands-free Deburring and Super ISO-finishing: The Free Sample Part Processing Program for 3D-Printed Parts and Machined Components Free Sample Processing Contact Dave Davidson at [email protected] for details. Parts that can be submitted for sample finishing include: 3D Printed parts (both metal and plastics), machined components, investment castings, forgings and others.

0 notes

Text

Hastelloy C276 Wire- excellent material for waste treatment

Hastelloy C276 alloy is particularly resistant to crevice and pitting corrosion due to high Molybdenum content. This alloy has high corrosion resistance at high temperatures. It is commonly used in various applications including pulp & paper production, waste treatment and chemical processing. The carbide precipitation during welding is minimized by the low carbon content to maintain corrosion resistance in as-welded structures. This nickel alloy is ideal for most chemical process applications in the as-welded condition due to its resistance to the formation of grain boundary precipitates in the weld heat-affected zone.

A wire is a metal produced in the form of a thin flexible thread and a mesh is a net made of woven or welded strands. Wire mesh is a grid formed by welding steel wires together at their intersections. It is manufactured in different sizes and types using various metals and alloys. Hastelloy C276 has excellent resistance to numerous corrosive media including strong oxidizing agents such as copper chloride, iron chloride and hot media, e.g. nitric acid, chlorine (dry), acetic acid, sulfuric acid, formic acid and phosphoric acid. Hastelloy C276 is used in environmental engineering in construction components in waste incineration plants and flue gas desulfurization plants, e.g. carrier systems, nozzle pipes, chimney linings, absorbers, raw gas inlet nozzles and claddings. It is used in chemical engineering in fittings, pipe linings in wet and dry zones, heat exchangers and mixers. This alloy is used in Pulp industry in bleach washers, chlorine injection nozzles and piping. Hastelloy C276 is used in oil and natural gas production in pumping systems in contact with sour gas in fittings, suction pipes and probes.

Hastelloy C276 alloy can be cold formed and hot formed and the hot forming temperature is between 1230 and 950°C. All standard forming techniques can be utilized and the material tends to work harden. Generally, solution annealing is repeated after hot forming and after cold forming with degrees of deformation greater than 15%. GWAT and GMAW gas metal arc welding processes are utilized for the welding of Hastelloy C276 alloy and it is preferably carried out on like materials or with Hastelloy C22 alloy. The fusion arc welding process is also used to weld the Hastelloy C276 alloy. The semi-finished products are in a stress-free, metallic bright condition and free of dirt. Minimum heat must be applied during welding in order to achieve optimal corrosion resistance. Preheating or secondary heat treatment is not necessary.

An essential non-traditional machining process used for machining difficult to machine materials like composites and inter-metallic materials, Intricate profiles is Wire Electric Discharge Machining (WEDM). A study was performed to optimize the process parameters during machining of Hastelloy C276 by wire-cut electrical discharge machining (WEDM). An effective approach was presented by this paper to optimize process parameters for Wire electric discharge machining (WEDM) was extensively used in tool and die industries. Precision and intricate machining are the strengths however time and surface quality still remains as major challenges while machining. Various input parameters were changed during the process including pulse off time (Toff), current, pulse on time (Ton), voltage and wire feed rate. The General Algorithm (GA) method L-27 orthogonal array was used to perform the optimization of analysis.

0 notes

Photo

Screen Printing Write-Up

Monday:

In alignment with my timetable, on the first day back from Easter I decided to take a trip to the Printing Rooms to begin the initial stages of creating screen prints ready for hand in, and to be exhibited in my graduation show.

Therefore I needed to get screens coated and exposed ASAP so I could begin printing my ‘Daniels’ portrait; featuring Katherine Waterston, synthesised from the upcoming film Alien: Covenant. When talking to Sonja, I had to rent two large screens; fitting two A3 layers per screen, to accommodate 4 layers of the A3 design. Whilst waiting for this to be coated and dried, I enquired about laser cutting space in the media lab.

Once the screens were dried, I exposed my designs and set about mixing the colours I needed in preparation for my allocated screen printing time on Tuesday afternoon 1:30 - 8:30. Mixing the colours in advance meant that I’d be able to expend more of my time & effort on actually screen printing in my located slot instead of colour mixing, and allowed me to take my time to play and explore possible colour choices, especially considering my partial colour blindness.

2 of my colours (black and grey) were almost identical to the original digital colours, however the two red tones I adjusted slightly, as I feel they worked better in print form in their new colour as they were more vibrant, visceral and engaging, and contrasted the grey with more visual impact.

Tuesday:

On the Tuesday, 1:30 - 8:30 slot, I was able to get 2 out of the 4 layers printed mostly without difficulty. As the colours were already mixed, all I had to do was tape up the screens and lock them into the frame, and get going.

I used single sheets of Snowdon Cartridge Paper, as they were sized as such that you can fit an A3 print on the page with a sufficient amount of border on all sides.

The initial red layer I had no problems with at all with, and the ink flowed cleanly and smoothly with no bleed or blank patches. The second red layer involving background detailing also went well, and although the ink was slightly more opaque than I had intended, I felt the texture arising from this instead worked in my favour and added a certain nuance to the piece.

A problem that occurred at this stage was that on one print the top right corner of the image came through as a partial print (which wasn’t too severe).

On another, when I had been adjusting alignment markings I had left a roll of tape on the worktop without realising, so that when I brought the screen down and pulled, the print was patchy. To start with I had thought the ink had dried in the screen and continued to pull repeatedly which fully overbred the screen and ruined the print. Thankfully after time, I realised my error and continued without issue, whilst only losing one print to this problem, and only several others through imperfect alignment.

At this stage I would easily reach an edition of 15 prints.

I then taped up my next screen in advance for printing on Wednesday, another afternoon slot.

Wednesday:

This was my final day of printing, and was undoubtedly the one filled with the most hassle and inconvenience. My starting problem was that my 3rd (grey) layer had very little in terms of detail that I could easily align with the previously printed layers, which made marking alignments on the table extremely difficult.

A solution to this problem was brought to me by Sonja, who showed me the method of taping down the black line work transparency; which the grey needed to lie beneath, onto the in progress prints. I then taped the grey transparency over this so it fitted flush to the line art. All I had to do then was to use this as an alignment guide. as the page size was already there, due to the transparencies being attached on top of it.

Once this 3rd layer had all been printed and had dried sufficiently, all I had left to print was my final layer.

When printing the black onto the test acetate and sorting out my page alignment tape marks, the ink dried into the screen, then the screen moved, I had to re-align, then the ink dried into the screen again. Thankfully I had taped my guidelines, so cheated my way through, and wetted the screen and forced the stuck ink through.

During printing at times the ink would get slightly stuck, but was an issue I could resolve. This final layer involved a lot of thin/small detailed marks, so this paired with the thick black ink was the culprit to the majority of my printing issues. Due to this I had to revisit and reprint some prints where the ink had blocked the screen, however it didn’t effect the quality as I was extremely precise and careful.

Print Evaluation:

Overall I’m extremely impressed with how the prints have come out. They’re a strong edition of 15; all in just one print run, without too much variation in regards to uniformity. There are a few areas where white shows through, but this usually looks more like a design decision than mistake. My use of colours were impactful and considered and work cohesively as a whole, I even feel that they’re improved upon compared to the original.

The use of the oversized paper acts as a great addition to the print, as it allowed me room to work with in production, but now in finality it means I can cut the best print down for exhibition (with a small border for edition & signature) or allows consumers to do with as they want. They have the option to place it in an oversized frame, or to have it mounted/cut down and framed.

I definitely feel that my time at JEALOUS meant that I was further informed as to how to approach the screen printing process with more ease and confidence. It made problem solving during the process much quicker, as I always knew how to adjust to problems such as sections of the screen over-flooding or drying in, and adapted to the situation.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introduction of excellent corrosion resistance properties of titanium and titanium plate materials

Titanium is a precious metal, and its relative density is small, high strength, and high specific strength. Next, I will introduce the corrosion resistance properties of titanium and titanium plate materials, I know the titanium pump, the occasion and function of the titanium plate pump can be used. It has excellent corrosion resistance in a specific environment. Titanium pump, titanium plate pump is a kind of strong corrosion-resistant pump, suitable for strong base and strong acid, so it is also called strong base and strong acid pump. The key to its strong corrosion resistance is titanium, a metal material.

After alloying, the medical titanium plate can greatly increase its strength (TC4 and so on are widely used).

Corrosion resistance of titanium and medical titanium plates Titanium materials have a high degree of stability in neutral or weakly acidic oxide solutions, for example, titanium and titanium plates in 100℃FeCl100℃CuC12, 100℃HgC1: (all Concentration), 60% AlCl2 and all concentrations of NaCl at 100°C are stable, and the oxides of many other metals of titanium are also stable in 100% monooxyacetic acid and 100% dioxyacetic acid, thus making titanium And titanium plates have been widely used in the above solutions.

Titanium and titanium plates have high corrosion resistance in gasoline, toluene, phenol, formaldehyde, trichloroethane, acetic acid, citric acid, monochloroethane, etc. However, in the case of boiling point and no gas, titanium is Formic acid with a mass fraction of less than 25% will be severely corroded. In a solution containing acetic anhydride, titanium is not only severely corroded, but also can cause pitting corrosion. For many complex organic media that are exposed to organic synthesis processes, such as In the production of propylene oxide, phenol, acetone, chloroacetic acid and other chemical media, the corrosion resistance of titanium and titanium plates is better than that of stainless steel and other structural materials. Titanium and titanium plates are also highly stable to oxidant solutions containing ions, such as 100qC sodium hypochlorite solution, oxygen water, gas (up to 75°C), sodium oxide solution containing hydrogen peroxide, etc. The corrosion resistance of titanium and titanium plates in wet chlorine gas exceeds that of other commonly used metals. This is because chlorine has a strong oxidation effect. Titanium and titanium plates can be in a stable passive state in wet chlorine. In order to maintain the passiveness of titanium in chlorine gas Sexuality requires a certain amount of water. The critical water content is related to oxygen pressure, flow rate, temperature and other factors, as well as the shape and size of titanium equipment or parts and the degree of mechanical damage to the titanium surface. Therefore, the critical water content of titanium passivation in oxygen in the literature is inconsistent It is generally believed that a mass fraction of 0.01% to 0.05% can be used as the critical moisture content of titanium in oxygen, but practical experience points out that in order to ensure the safe use of titanium equipment in oxygen, sometimes the water mass fraction is 0.6% is not enough, it needs to be up to 1.5%. The critical water content also increases as the temperature of the chlorine gas increases and the gas flow rate decreases.

gr2 pure titanium bar suppliers gr9 ti-3al-2.5v titanium foil for sale f9 titanium forging price gr23 ti-6al-4v eli titanium sheet price

0 notes

Text

vimeo

Hell & High Water Multi-layer Acetate Illo Timelapse Video 🌊🔥

A lil timelapse vid of the drawing process for my recent Cover Spread illustration for Going Down Swinging Edition 43.

The Edition 43 Launch Event will be down in Naarm/Melbourne at The Mission to Seafarers at 7PM on 22 Sep!

[ID: A video of a top-down view of a desk showing an illustration being drawn on transparent acetate with POSCA markers. The finished illustration is of blue and yellow flames rising out of pink waves on a black background]

#Drawing#Illustration#Art#Editorial illustration#Magazine Cover#Traditional#POSCA#POSCA Markers#Acetate#Wet Media Acetate#Vimeo

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cellulose Acetate Propionate Report 2019-2027 | Top Manufacturers, Types and Applications

Cellulose Acetate Propionate Market: Introduction

Cellulose acetate propionate is a free-flowing powder with low-odor. It is especially used in printing inks and clear overprint varnishes, and nail lacquer topcoats due of its wide solubility in ink solvents and compatibility with other resins used in printing inks.

Cellulose acetate propionate exhibits excellent anti-blocking properties. Its grease resistance is superior to that of many other film formers. Cellulose acetate propionate helps reduce surface defects such as pinholes and craters; and typically improves wetting, block resistance, adhesion, and solvent release, thus enabling faster print and coat speeds when used in inks and coatings.

Key Drivers of Global Cellulose Acetate Propionate Market

The global cellulose acetate propionate market is driven by the increase in application of cellulose acetate propionate in various products such as printing inks and coating products. The chemical compound is used to clear overprint varnishes. It is also used as a film coating material.

Cellulose acetate propionate is primarily employed as a pharmaceutical excipient due to its solubility that is dependent on the pH of aqueous media. Cellulose acetate propionate-based enteric coatings are resistant to acidic gastric fluids, but are easily soluble in mildly basic medium of the intestine.

Enactment of supportive regulatory framework by various regulatory bodies, such as the FDA and the EPA, is driving the global cellulose acetate propionate market

Film Coating Application Segment to Dominate Global Market

Based on application, the film coating segment dominated the global cellulose acetate propionate market in 2018, owing to the extensive usage of film coatings in the pharmaceutical industry. The film coating segment is anticipated to expand at a significant pace owing to the increase in demand for cellulose acetate propionate for controlled release formulations in film coatings for capsules and tablets.

The cellulose acetate propionate compound is used to form rigid capsule in microencapsulation. Furthermore, it can be employed as a supporting material during the usage of the spray drying technique in the pharmaceutical industry.

Request a PDF Brochure @ https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=B&rep_id=75369

Availability of Substitutes to Hamper the Market for Cellulose Acetate Propionate

Easy availability of substitutes is expected to hamper the market for cellulose acetate propionate during the forecast period.

Key substitutes of cellulose acetate propionate include other cellulose compounds such as cellulose acetate butyrate, which are available at low cost

Key Players Operating in Global Market

The global cellulose acetate propionate market is highly consolidated with a few large players dominating the market. The market includes a large number of domestic and international market players. Integration by key players from procurement of raw material to distribution of the final product across the value chain is also a key strategy adopted in this market. Additionally, companies operating in the cellulose acetate propionate market are conducting research in low-cost production methods to produce chemicals by investing significantly in research and development activities.

Request a COVID-19 Impact Analysis @ https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=covid19&rep_id=75369

Explore Transparency Market Research’s award-winning coverage of the global Chemicals and Materials Industry.

0 notes

Text

Cellulose Acetate Market Share,Growth,Trends,and Forecast, 2019 – 2027

Cellulose Acetate Propionate Market: Introduction

Cellulose acetate propionate is a free-flowing powder with low-odor. It is especially used in printing inks and clear overprint varnishes, and nail lacquer topcoats due of its wide solubility in ink solvents and compatibility with other resins used in printing inks.

Cellulose acetate propionate exhibits excellent anti-blocking properties. Its grease resistance is superior to that of many other film formers. Cellulose acetate propionate helps reduce surface defects such as pinholes and craters; and typically improves wetting, block resistance, adhesion, and solvent release, thus enabling faster print and coat speeds when used in inks and coatings.

Read report Overview-

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/cellulose-acetate-propionate-market.html

Key Drivers of Global Cellulose Acetate Propionate Market

The global cellulose acetate propionate market is driven by the increase in application of cellulose acetate propionate in various products such as printing inks and coating products. The chemical compound is used to clear overprint varnishes. It is also used as a film coating material.

Cellulose acetate propionate is primarily employed as a pharmaceutical excipient due to its solubility that is dependent on the pH of aqueous media. Cellulose acetate propionate-based enteric coatings are resistant to acidic gastric fluids, but are easily soluble in mildly basic medium of the intestine.

Enactment of supportive regulatory framework by various regulatory bodies, such as the FDA and the EPA, is driving the global cellulose acetate propionate market

Are you a start-up willing to make it big in the business? Grab an exclusive PDF sample of this report

Film Coating Application Segment to Dominate Global Market

Based on application, the film coating segment dominated the global cellulose acetate propionate market in 2018, owing to the extensive usage of film coatings in the pharmaceutical industry. The film coating segment is anticipated to expand at a significant pace owing to the increase in demand for cellulose acetate propionate for controlled release formulations in film coatings for capsules and tablets.

The cellulose acetate propionate compound is used to form rigid capsule in microencapsulation. Furthermore, it can be employed as a supporting material during the usage of the spray drying technique in the pharmaceutical industry.

Availability of Substitutes to Hamper the Market for Cellulose Acetate Propionate

Easy availability of substitutes is expected to hamper the market for cellulose acetate propionate during the forecast period.

Key substitutes of cellulose acetate propionate include other cellulose compounds such as cellulose acetate butyrate, which are available at low cost.

REQUEST FOR COVID19 IMPACT ANALYSIS –

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=covid19&rep_id=75369

Asia Pacific to Hold Significant Share for Global Cellulose Acetate Propionate Market

In terms of region, the global cellulose acetate propionate market can be divided into North America, Europe, Asia Pacific, Latin America, and Middle East & Africa

Asia Pacific is the major region of the global cellulose acetate propionate market. Growth in the pharmaceutical industry in countries of Asia Pacific is expected to boost the demand for cellulose acetate propionate in the region. Furthermore, easy availability of raw materials is estimated to augment the production of cellulose acetate propionate in the region.

Presence of a well-established pharmaceutical sector in North America is the major factor driving the consumption of cellulose acetate propionate in the region. The market in Europe has been expanding significantly. The region is experiencing high demand for pharmaceutical products obtained from natural derivatives.

Key Players Operating in Global Market

The global cellulose acetate propionate market is highly consolidated with a few large players dominating the market. The market includes a large number of domestic and international market players. Integration by key players from procurement of raw material to distribution of the final product across the value chain is also a key strategy adopted in this market. Additionally, companies operating in the cellulose acetate propionate market are conducting research in low-cost production methods to produce chemicals by investing significantly in research and development activities.

Key players operating in the global cellulose acetate propionate market include:

Daicel Corporation

China National Tobacco Corporation

Acordis Cellulostic Fibers Inc.

Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings Corporation

Sichuan Push Acetati LLC

Solvay SA

Eastman Chemical Company

Rayonier Advanced Materials Inc.

Celanese Corporation and Sappi Limited

Read our Case study at :

https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/casestudies/chemicals-and-materials-case-study

0 notes

Text

Water-Based Adhesive Market | Industry Size Analysis and Demand with Forecast Overview to 2023

Water-Based Adhesive Market Information by Resin Type (PVA Emulsion, PAE, VAE Emulsion, SB latex, PUD, VAA), Application (Tapes & Labels, Paper & Packaging, Woodworking, Building & Construction, Automotive), and Region (Asia-Pacific, North America, Europe, and Others)—Forecast till 2023

Market Overview

Water-based adhesives also known as waterborne adhesives content carrier fluid and additives to reduce its viscosity to be applied at different thickness. These adhesives are formulated using either natural polymers or soluble synthetic polymers.

Water-based adhesives are gaining high importance in the market owing to environmentally friendly and economical alternative to solvent-borne adhesives. They are wet bonding, therefore at least one substrate has to be water permeable to allow water to escape from the bond line. Owing to its flexibility and quick setting time, major customers of water-based adhesives are the paper & packaging, building & construction, automotive and woodworking among others.

Competitive Analysis

Some of the key players in the global water-based adhesive are Henkel AG & Company, KGaA (Germany), Arkema (France), Sika AG (Switzerland), H.B. Fuller Company (US), DowDupont (US), 3M (US), DIC Corporation (Japan), Ashland Inc. (US), Akzo Nobel N.V. (Netherlands), and PPG Industries, Inc. (US) among others.

Market Segmentation

According to MRFR analysis, the global Water-Based Adhesives Market has been segmented by resin type, application, and region.On the basis of resin type, the market has been segmented into polyvinyl acetate emulsion (PVA), acrylic polymer emulsion (PAE), vinyl acetate ethylene emulsion (VAE), styrene butadiene latex, polyurethane dispersion (PUD), vinyl acetate acrylates (VAA) and others. Acrylic polymer emuslion segment accounted for the largest market share in the global water-based adhesives market in 2017.

These adhesives are heterogenous mixture consisting of dispersed liquid in aqueous phase and provides balance between shear, stack and peel of the bond. It is widely used in packaging materials like paper bags, tapes, labels, automotive upholstery and leather binding. Growing demand for packaging application due to increase in trading activities is expected to propel demand for acrylic polymer emulsion, which in turn, driving the demand for water-based adhesives market. Moreover, increasing in number of educational centers and institutions in emerging economies has contributed to rise in bookbinding, carton, labels and paperboard decals are expected to offer a bolstering opportunity for the manufacturers of water-based adhesives.

Based on applications, the market has been segmented into paper & packaging, tapes & labels, building & construction, automotive, woodworking and others. Paper & packaging segment accounted for the largest market share in the global market owing to the increasing demand for lightweight packaging materials in industries like FMCG, pharmaceuticals, and food & beverages.

Increasing in disposable income and high demand for consumer goods are expected to drive the market growth. Tapes & labels are expected to witnessed moderate growth rate during the forecast period. Tapes & labels are prominently used in packaging of electronic devices, medical equipment’s, drug delivery system and industrial goods. Thus, increase in demand for flexible packaging is likely to offer numerous opportunities for end use customers in the global water-based adhesive market.

Regional Analysis

Asia-Pacific accounted for largest market share owing to growing infrastructure activities and rise in automotive production in emerging countries such as India, Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Increasing demand for paper packaging materials along with increasing disposable income are expected to drive the demand for water-based adhesives over the assessment period.

The high demand from major end-use industries such as paper & packaging, building & construction, automotive, and woodworking is driving the demand for water-based adhesives in the North American and European region. However, the declining sales of print media owing to digital marketing is likely to decline the demand for water-based adhesives.

The Middle East & Africa is driving the global water-based adhesives market owing to the presence of infrastructural hubs present in the region.

Intended Audience:

Water-Based Adhesive manufacturers

Traders and distributors of Water-Based Adhesive

Adhesives & Sealant Producers

Potential investors

Raw material suppliers

Research laboratories

Access Full Report Details @ https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/water-based-adhesive-market-6987

#Water-Based Adhesive#Water-Based Adhesive Market Size#Water-Based Adhesive Market Share#Water-Based Adhesive Market Growth

0 notes

Text

Amphoteric Surfactant Market | Analysis and Forecast up to 2024

Surfactants are chemical compounds that increase cleaning efficiency by wetting, emulsifying, dispersing, or modifying the lubricity of water-based compositions. They are used as detergents, emulsifiers, foaming agents, wetting agents, and dispersants. Surfactants are manufactured by using either of the two distinct feedstock: natural vegetable oils and petrochemicals. According to the composition of their polar head, surfactants are classified into anionic, nonionic, amphoteric, and cationic surfactants. Amphoteric surfactants are further classified into amphoteric acetates, betaines, and sultains. The use of amphoteric surfactants results in better performance in applications involving hard water media and high temperature environments. Amphoteric surfactants are used in diverse application areas such as personal care and household detergency, emulsification, and foaming. Rising demand in the personal care and home care industries is expected to drive the global surfactants market in the next few years.

Planning to lay down strategy for the next few years? Our report can help shape your plan better.

The major classes of amphoteric surfactants are betaines and propionates. These are prominently used in the personal care market. These two classes of amphoteric surfactants can be sub-segmented into cocamidopropyl betaine, dimer amido propyl betaine, cetyl betaine, lauric myristic amido betaine, lauramphopropionate, and coco betaines. Amphoteric surfactants have excellent properties such as good detergency, hard water compatibility, foaming properties, mild behavior, conditioning properties, and biodegradability. They cause less irritation to human skin and eyes, and are applicable in a wide pH range. Moreover, amphoteric surfactants are compatible with nonionic, anionic, and cationic surfactants and act as viscosity builders for anionic surfactant solutions. Due to all these properties, mild amphoteric surfactants are widely used as secondary surfactants in products such as shower gels, shampoos, liquid soaps, and foam baths. Furthermore, they are employed in liquid detergent products such as all-purpose cleaners, dishwashing liquids, and car cleaners.

Asia Pacific is the largest market for amphoteric surfactants due to significant demand from India, China, Japan, and South Korea. Moreover, Asia Pacific is anticipated to be the fastest growing market for amphoteric surfactants, considering the rising demand in countries in Southeast Asia including Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam. North America and Europe are the second and third largest markets for amphoteric surfactants. These are likely to record dismal growth rates due to slow recovery from the economic slowdown. On the contrary, countries in the Rest of the World (RoW) such as Brazil, Mexico, Egypt, South Africa, and Nigeria are witnessing strong signs of growth. Therefore, the region is expected to become the second fastest growing market for amphoteric surfactants across the globe.

To obtain all-inclusive information on forecast analysis of Global Market, request a PDF brochure here.

Major factors driving the global amphoteric surfactants market include steep rise in demand for skin-friendly surfactants in the personal care and home care industries. Amphoteric surfactants are skin-friendly chemical compounds; therefore, they are likely to replace conventional surfactants that may harm the skin. Applications of amphoteric surfactants are anticipated to rise significantly considering the ongoing research and development activities undertaken by key players in the industry. Development of a new and cost effective range of amphoteric surfactants and growing awareness regarding the use of sulfur-free personal care products are also anticipated to lead to a tremendous growth potential in the global market for less costly and more skin friendly surfactants.

Major manufacturers of amphoteric surfactants include Clariant Corporation, Akzo Nobel N.V., Huntsman Corporation, BASF SE, Lubrizol Corporation, Evonik Industries AG, Stepan Company, and Lonza Spa.

0 notes

Text

Amphoteric Surfactant Market : Quantitative Market Analysis, Current And Future Trends 2024

Surfactants are chemical compounds that increase cleaning efficiency by wetting, emulsifying, dispersing, or modifying the lubricity of water-based compositions. They are used as detergents, emulsifiers, foaming agents, wetting agents, and dispersants. Surfactants are manufactured by using either of the two distinct feedstock: natural vegetable oils and petrochemicals. According to the composition of their polar head, surfactants are classified into anionic, nonionic, amphoteric, and cationic surfactants. Amphoteric surfactants are further classified into amphoteric acetates, betaines, and sultains. The use of amphoteric surfactants results in better performance in applications involving hard water media and high temperature environments. Amphoteric surfactants are used in diverse application areas such as personal care and household detergency, emulsification, and foaming. Rising demand in the personal care and home care industries is expected to drive the global surfactants market in the next few years.

Read Report Overview @ https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/amphoteric-surfactant-market.html

The major classes of amphoteric surfactants are betaines and propionates. These are prominently used in the personal care market. These two classes of amphoteric surfactants can be sub-segmented into cocamidopropyl betaine, dimer amido propyl betaine, cetyl betaine, lauric myristic amido betaine, lauramphopropionate, and coco betaines. Amphoteric surfactants have excellent properties such as good detergency, hard water compatibility, foaming properties, mild behavior, conditioning properties, and biodegradability.

They cause less irritation to human skin and eyes, and are applicable in a wide pH range. Moreover, amphoteric surfactants are compatible with nonionic, anionic, and cationic surfactants and act as viscosity builders for anionic surfactant solutions. Due to all these properties, mild amphoteric surfactants are widely used as secondary surfactants in products such as shower gels, shampoos, liquid soaps, and foam baths. Furthermore, they are employed in liquid detergent products such as all-purpose cleaners, dishwashing liquids, and car cleaners.

Request Report Brochure @ https://www.transparencymarketresearch.com/sample/sample.php?flag=B&rep_id=13496

Asia Pacific is the largest market for amphoteric surfactants due to significant demand from India, China, Japan, and South Korea. Moreover, Asia Pacific is anticipated to be the fastest growing market for amphoteric surfactants, considering the rising demand in countries in Southeast Asia including Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam. North America and Europe are the second and third largest markets for amphoteric surfactants.

These are likely to record dismal growth rates due to slow recovery from the economic slowdown. On the contrary, countries in the Rest of the World (RoW) such as Brazil, Mexico, Egypt, South Africa, and Nigeria are witnessing strong signs of growth. Therefore, the region is expected to become the second fastest growing market for amphoteric surfactants across the globe.

0 notes

Text

Hastelloy C22 and its Application in the Chemical Processing Industry

Hastelloy C22 is a nickel-chromium-molybdenum-tungsten alloy that exhibits improved resistance to pitting, stress corrosion cracking and crevice corrosion. On one hand, the presence of chromium in high amount makes it extremely resistant to oxidizing media. While on the other hand, the tungsten and molybdenum content offers good resistance to reducing media. This C22 alloy also displays excellent resistance to oxidizing aqueous solutions that includes wet chlorine and other mixtures that contain nitric acid or oxidizing acids having chlorine ions.

Some of the other corrosive agents Hastelloy C-22 alloys are resistant to are wet chlorine, oxidizing acid, different chlorides, seawater, formic and acetic acids, ferric and cupric chlorides, brine and many other tainted or mixed chemical solutions that are both inorganic and organic. It also offers optimal resistance to different environments where oxidizing and reducing conditions are met in process streams.

The C22 alloy repels the formation of grain-boundary precipitates on the weld heat-affected area. This makes it appropriate for most of the chemical process applications even in the welded state. The alloy is extremely resistant to a number of aggressive corrosive media. The welding characteristics is similar to that of the C-276 alloy.

Its application in chemical processing

This corrosion-resistant Hastelloy alloy C22 is widely used in the chemical processing industries. The fact that it assures a reliable performance, improves its chances of growth and acceptance in several industries like oil and gas, geothermal, solar energy and pharmaceutical. The reason why Hastelloy C22 process equipment is preferred to be used are due to its outstanding localized corrosion resistance, high resistance to uniform attack, excellent resistant to stress corrosion cracking and the simplicity of welding and fabricating.

The Hastelloy C22 alloy is a “C-type” alloy. It exhibits outstanding resistance in oxidizing media along with a superior resistance to the non-oxidizing environments. This character of the C22 alloy represents a true performance break-through in the applications of chemical process equipment. The alloy C22 should never be used above service temperatures of 1250° F as it can lead to the formation of detrimental phases at this temperature.

In chemical industries it can be used in many applications like chlorination systems, pulp and paper bleach plants, gas scrubbers, pickling systems, sulfur dioxide scrubbers and nuclear fuel reprocessing.

Other applications

· It is used in pharmaceutical industries for making hastealloy C22 bar, tubing and fittings to avoid any kind of contamination which can be caused by failures related to corrosion

· In the manufacturing of cellophane

· In the chlorination systems

· For the production of pesticides

· In Ignition scrubber systems

· For the processing of waste water

· In the manufacturing of phosphoric acid and sulfur dioxide cooling towers, electro-galvanizing rolls, flue gas scrubber systems and nuclear fuel processing.

Machinability

Hastelloy C-22 is considered a little difficult for machining. But it can still be machined by using conventional production methods that are used in case of other alloys at an acceptable rate. In the process of machining, C-22 can harden fast, generate a lot of heat, get attached to the surface of the cutting tool, resist the removal of metal due to its high shear strength.

0 notes

Text

Debunking the Myths of Robert Capa on D-Day

I want to give you a brief overview of an investigation that began almost five years ago, led by me but involving the efforts of photojournalist J. Ross Baughman, photo historian Rob McElroy, and ex-infantryman and amateur military historian Charles Herrick.

Our project, in a nutshell, dismantles the 74-year-old myth of Robert Capa’s actions on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and the subsequent fate of his negatives. If you have even a passing familiarity with the history of photojournalism, or simply an awareness of twentieth-century cultural history on both sides of the Atlantic, you’ve surely heard the story; it’s been repeated hundreds, possibly thousands of times:

Robert Capa landed on Omaha Beach with the first wave of assault troops at 0630 on the morning of June 6, 1944 (D-Day), on freelance assignment from LIFE magazine.

He stayed there for 90 minutes, until he either inexplicably ran out of film or his camera jammed.

During that time he made somewhere between 72 and 144 35mm b&w exposures of the Allied invasion of Normandy on Kodak Super-XX film.

Upon landing back in England the next day, he sent all his film via courier to assistant picture editor John Morris at LIFE’s London office, instead of delivering it in person.

This shipment included pre-invasion reportage of the troops boarding and crossing the English Channel, the just-mentioned coverage of the battle on Omaha Beach, and images of medics tending to the wounded on the return trip.

When the film finally arrived, around 9 p.m., the head of LIFE’s London darkroom, one “Braddy” Bradshaw, inexplicably assigned the task of developing these crucial four rolls of 35mm Omaha Beach images to one of the least experienced members of his staff, 15-year-old “darkroom lad” Denis Banks.

After successfully processing the 35mm films, in his haste to help Morris meet the looming deadline Banks absentmindedly closed the doors of the darkroom’s film-drying cabinet, which inexplicably were “normally kept open.” Inexplicably, nobody noticed that Banks had closed them.

As a result, after “just a few minutes,” that enclosed space with a small electric heating coil on its floor inexplicably became so drastically overheated that it melted the emulsion of Capa’s 35mm negatives.

Notified of this by the horrified Banks, Morris rushed to the darkroom, discovering that eleven of Capa’s negatives had survived, which he “saved” or “salvaged,” and which proved just sufficient enough to fulfill this crucial assignment to the satisfaction of LIFE’s New York editors.

That darkroom catastrophe blurred slightly the remaining negatives, “ironically” adding to their expressiveness. Furthermore, as a result of the overheating, the emulsion on those eleven negatives inexplicably slid a few millimeters sideways on their acetate backing, resulting in a visible intrusion of the film’s sprocket holes into the image area.

Robert Capa, D-Day images from Omaha Beach, contact sheet, screenshot from TIME video (May 29, 2014), annotated.

That standard narrative constitutes photojournalism’s most potent and durable myth. From it springs the image of the intrepid photojournalist as heroic loner, risking all to bear witness for humanity, yet at the mercy of corporate forces that, by cynical choice or sheer ineptitude, can in an instant erase from the historical record the only traces of a crucial passage in world events.

Jean-David Morvan and Séverine Tréfouël, “Omaha Beach on D-Day” (2015), cover

Moreover, it represents, arguably, the most widely familiar bit of folklore in the history of the medium of photography — one that appears not only in histories of photography and photojournalism, in biographies of and other books about Capa, but in novels, graphic novels, the autobiographies of such famous people as actress Ingrid Bergman and Hollywood director Sam Fuller, assorted films, and even in videos of Steven Spielberg talking about his inspirations for the opening scenes of his film Saving Private Ryan, not to mention countless retellings in the mass media.

Charles Christian Wertenbaker, “Invasion!” (1944), cover

An early version of this story started to circulate immediately after D-Day, made its first half-formed appearance in print in the fall of 1944, and received its full formal authorization with the publication of Capa’s heavily fictionalized memoir, Slightly Out of Focus, in the fall of 1947. Since then it’s been reiterated endlessly, either by John Morris or by others quoting or paraphrasing Capa’s or Morris’s version of the tale. It gets retold in the mass media with special frequency on every major celebration of D-Day — the 50th anniversary, the 60th, most recently the 70th. In short, it has gradually achieved the status of legend. That this legend went unexamined for seven decades serves as a measure of its appeal not just to photojournalists, to others involved professionally with photography, and to the medium’s growing audience, but to the general public.

For 70 years, despite the many glaring holes in it, no one questioned this story — least of all those in charge at the International Center of Photography, which houses the Capa Archive. These figures have included the late Cornell Capa, Robert’s younger brother and founder of ICP; the late Richard Whelan, Robert’s authorized biographer and the first curator of that archive; and Whelan’s successor in that curatorial role, Cynthia Young.

Ironically, two celebrations of the 70th anniversary of Capa’s D-Day images provoked our investigation. The first came as a flattering profile of John Morris, written by Marie Brenner for Vanity Fair magazine. Morris served as assistant picture editor in LIFE’s London bureau for that magazine’s D-Day coverage, and in this Brenner piece he recounts his version of the Capa-LIFE D-Day myth once more. Shortly thereafter, on May 29, 2014, TIME Inc. — the corporation that had commissioned and published Capa’s D-Day images back in 1944 — posted a video at its website celebrating those photographs, which some refer to as “the magnificent eleven.”

A division of Magnum Photos, the picture agency Capa founded with his colleagues in 1947 (the same year he published his memoir), produced that video for TIME. The International Center of Photography licensed the use of Capa’s images for that purpose. And none other than John Morris, by then 97 years old and living in Paris, provided the voice-over, his boilerplate narrative of those events. In short, this video involved the combined energies of the individual and institutional forces involved in the creation and propagation of this myth — what I came to define as the Capa Consortium.

The Capa Consortium, Keynote slide, © 2015 by A. D. Coleman

Assorted elements of those two virtually identical versions of the standard story, Brenner’s and Time Inc.’s, struck J. Ross Baughman as illogical and implausible. The youngest photojournalist ever to win a Pulitzer Prize (in 1978, at the age of 24), Baughman is an experienced combat photographer who has worked in war zones in the Middle East, El Salvador, Rhodesia, and elsewhere. As the founder of the picture agency Visions, which specialized in such work, he’s also an experienced picture editor. Ross contacted me to ask if I would publish his analysis at my blog, Photocritic International, as a Guest Post. I agreed.

In the editorial process of fact-checking and sourcing Baughman’s skeptical response to the standard narrative provided by Morris in that video, my own bulls**t detector began to sound the alarm. I realized that Baughman’s critique raised more questions than it answered, requiring much more research and writing than I could reasonably request from him. I decided to pursue those issues further myself.

This immersed me in the Capa literature for the first time. Speaking as a scholar, that came as a rude awakening. The most immediate shock hit as I read through a half-dozen print and web versions of Morris’s account of those events — in Brenner’s 2014 puff piece, in Morris’s 1998 memoir, and in various interviews, profiles, and articles — and watched at least as many online videos and films featuring Morris rehashing this tale. I realized that the only portion of this story that Morris claimed to have witnessed firsthand, the loss of Capa’s films in LIFE’s London darkroom, could not possibly have happened the way he said it did.

In retrospect, I cannot understand how so many people in the field, working photographers among them, accepted uncritically the unlikely, unprecedented story, concocted by Morris, of Capa’s 35mm Kodak Super-XX film emulsion melting in a film-drying cabinet on the night of June 7, 1944.

Anyone familiar with analog photographic materials and normal darkroom practice worldwide must consider this fabulation incredible on its face. Coil heaters in wooden film-drying cabinets circa 1944 did not ever produce high levels of heat; black & white film emulsions of that time did not melt even after brief exposure to high heat; and the doors of film-drying cabinets are normally kept closed, not open, since the primary function of such cabinets is to prevent dust from adhering to the sticky emulsion of wet film.

No one with darkroom experience could have come up with this notion; only someone entirely ignorant of photographic materials and processes — like Morris — could have imagined it. Embarrassingly, none of that set my own alarm bells ringing until I started to fact-check the article by Baughman that initiated this project, close to fifty years after I first read that fable in Capa’s memoir.

This is one of several big lies permeating the literature on Robert Capa. Certainly Capa knew it was untrue when he published it in his memoir; he had gotten his start in photography as a darkroom assistant in Simon Guttmann’s Dephot photo agency in Berlin. And Cornell Capa also knew that; he had cut his eyeteeth in the medium first by developing the films of his brother, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and David Seymour in Paris, then by working in the darkroom of the Pix photo agency in New York, then by moving on to fill the same role at LIFE magazine before becoming a photographer in his own right. My belated recognition of that fact led me to ask the obvious next question: If that didn’t happen to Capa’s 35mm D-Day films, what did? And if all these people were willing to lie about this, what were they covering up?

So, building on Baughman’s initial provocation, I began drafting my own extensions of what he’d initiated — and our investigation was launched.

In December of 2017 I published the 74th chapter of our research project. You’ll find all of it online at my blog; the easiest way to get to the Capa D-Day material is by using the url capadday.com. During these years I have become intimately familiar with a large chunk of what others have written and said about Capa and his D-Day coverage.

In my opinion, the bulk of the published writing and presentations in other formats (films, videos, exhibitions) devoted to the life and work of photojournalist Robert Capa qualifies as hagiography, not scholarship. Capa’s own account of his World War II experiences, Slightly Out of Focus, consistently proves itself inaccurate and unreliable, masking its sly self-aggrandizement with wry humor and self-deprecation. Morris’s memoir repeats Capa’s combat stories unquestioningly, adding to those his own dubious saga of the “ruined” negatives.

Richard Whelan, “This Is War! Robert Capa at Work” (2007), cover

Richard Whelan’s books, widely considered the key reference works on Capa, simply quote or paraphrase Capa and Morris uncritically, perhaps because they were sponsored, subsidized, published, and endorsed most prominently and extensively by the estate of Robert Capa and the Fund for Concerned Photography (both controlled by Capa’s younger brother Cornell) and the International Center of Photography, founded by Cornell, who also served as ICP’s first director.

Produced in most other cases under Cornell’s watchful eye or the supervision of one or another participant in the Capa Consortium, the remainder of the serious, scholarly literature on Robert Capa has almost all been subject to Cornell’s approval and reliant on either the problematic principal reference works or on Robert Capa materials stored in Cornell’s private home in Manhattan, with access dependent on his consent. Consequently, it constitutes an inherently limited corpus of contaminated research, fatally corrupted by its unswerving allegiance to both its patron and its patron saint. Such bespoke scholarship becomes automatically suspect.

Cornell Capa, interview with Barbaralee Diamonstein, 1980, screenshot

The second failing of this heap of compromised materials resides in its reliance on untrustworthy and far from neutral sources: Robert Capa, with a demonstrated penchant for self-mythification; his younger brother Cornell, a classic “art widower” with every reason to enhance his brother’s reputation; and Robert’s close friend and Cornell’s, John Morris, whose own stature in the field premises itself on the Capa D-Day legend. Only Alex Kershaw’s unauthorized Capa biography, Blood and Champagne, published in 2002, maintains its independence from Cornell’s influence, but at the cost of losing access to the primary research materials and consequently reiterating the erroneous information in the accounts of Capa, Morris, and Whelan. Virtually everything else published about Capa, including those stories in the mass media that appear predictably every five years along with celebrations of D-Day, unquestioningly presents the prevailing myth.

This Capa literature suffers from a third fundamental flaw: Those generating it (with the exception of Capa himself and his brother Cornell), have no direct, hands-on knowledge of photographic production, no military background (significant in that Robert Capa’s most important work falls under the heading of combat photography), and no forensic skills pertinent to the analysis of photographic materials. Nor were they encouraged by their patron, Cornell Capa, to make up for those deficiencies by involving others with those competencies in their projects. Instead, their privileged relationship to the primary materials, along with the availability of a prominent and well-funded platform at ICP, enabled them to effectively invent whatever suited them, pleased their benefactor, and served their purposes.

Responsible Capa scholarship, therefore, must begin by distrusting the extant literature, turning instead to the photographs themselves and relevant documents that the Capa estate and ICP do not control and to which they therefore cannot prohibit access. Those materials lie at the core of our research project.

Here’s a short summary of what we’ve found:

Capa sailed across the English Channel on the U.S.S. Samuel Chase.

According to the official history of the U.S. Coast Guard, fifteen waves of LCVPs (commonly called Higgins boats) carrying troops left the U.S.S. Samuel Chase for Omaha Beach that morning. Capa almost certainly rode in with Col. Taylor and his staff, the command group of Company E of the 16th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 1st Division, to which Capa had been assigned. They constituted part of the thirteenth wave.

That wave arrived at the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach at 8:15, a half hour after the last of the 16th Infantry Regiment’s nine rifle companies. We can see from Capa’s images that numerous waves of troops preceded them.

Using distinctive landmarks visible in Capa’s photos, Charles Herrick has pinpointed exactly where Capa landed on Easy Red: the beach at Colleville-sur-Mer. Gap Assault Team 10 had charge of the obstacles in that sector. An existing exit off this sector made it possible to reach the top of the bluffs with relative ease. Col. Taylor would become famous for announcing to the hesitant troops he found there, “Two kinds of people are staying on this beach, the dead and those who are going to die — now let’s get the hell out of here,” and urging them up the Colleville-sur-Mer draw to the bluffs.

Robert Capa, CS frame 4, neg. 32, detail, annotated

Fortuitously, that stretch of Easy Red represented a seam in the German defenses, a weak point at the far end of the effective range of two widely separated German blockhouses. Both cannon fire and small-arms fire there proved relatively light — one reason for the success of Gap Assault Team 10 in clearing obstacles in that area. This explains why, contrary to LIFE’s captions and Capa’s later narrative, his images show no carnage, no floating bodies and body parts, no discarded equipment, and no bullet or shell splashes. This also explains why the Allies broke through early at that very point.

Capa did not run out of film, nor did his camera jam, nor did seawater damage either his cameras or his film. In his memoir, Capa first implies that he exposed at most two full rolls of 35mm film — one roll in each of his two Contax II rangefinder cameras, 72 frames in all — at Omaha Beach. By the end of that chapter, this has somehow grown to “one hundred and six pictures in all, [of which] only eight were salvaged.” John Morris claims he received 4 rolls of Omaha Beach negatives from Capa. We find no reason to believe that Capa made more than the ten 35mm images of which we have physical evidence.

Capa made the first five of those images while standing for almost two minutes on the ramp of the landing craft that brought him there. In them we see Capa’s traveling companions carrying not small-arms assault weapons but bulky oilskin-wrapped bundles, most likely radios and other supplies for the command post they meant to establish.

Capa made his sixth exposure from behind a mined iron “hedgehog,” one of many such obstacles protecting what Nazi Gen. Erwin Rommel called the “Atlantic Wall.” He made his last four exposures — including “The Face in the Surf” — from behind Armored Assault Vehicle 10, which was sitting in the surf shelling the gun emplacements on the bluffs.

Capa described Armored Assault Vehicle 10, which appears on the left-hand side of several of his images, as “one of our half-burnt amphibious tanks.” In fact, it was a modified American tank, a “wading Sherman,” not amphibious (merely waterproofed to the top of its treads) and not burnt out; later images made by others of that stretch of Easy Red show this tank undamaged, closer to the dry beach, and apparently in action. Taken in conjunction with the known presence at that point of Gap Assault Team 10, the large numeral 10 on this vehicle’s rear vent suggests that it was a so-called “tank dozer,” one of which landed with each demolition team that morning. The U.S. Army had modified these tanks by adding detachable bulldozer “blades,” so that they could clear the debris after the engineers blew up the obstacles.

Not incidentally, both the time and place of Capa’s arrival on Easy Red contradict the current identification of Huston “Hu” Riley as “The Face in the Surf” in Capa’s penultimate exposure on Easy Red, as well as the earlier identification of “The Face in the Surf” as Pfc. Edward J. Regan. Both these soldiers arrived at different times than Capa, and on different sections of the beach. Thus the identity of “The Face in the Surf” remains unknown.

After no more than 30 minutes on the beach, and perhaps as little as 15 minutes there, Capa ran to a landing craft, LCI(L)-94, where he took shelter before its departure around 0900.

Capa claimed that he reached the dry beach and then experienced a panic attack, causing him to escape from the combat zone. We must consider the possibility that he suffered from what they then called “shell shock” and we now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But we must also consider the possibility that, even before setting forth that morning, Capa made a calculated decision to leave the battlefield at the first opportunity, in order to get his films to London in time to make the deadline for LIFE’s next issue; if he missed that deadline, any images of the landing would become old news and his effort and risks in making them would have been for naught.

No fewer than four witnesses place Capa on this vessel, LCI(L)-94. The first three were crew members Charles Jarreau, Clifford W. Lewis, and Victor Haboush. According to Capa, once he reached LCI(L)-94 he put away his Contax II, working thenceforth only with his Rolleiflex. One of the 2–1/4″ images he made while aboard this vessel, published in the D-Day feature story in LIFE, shows Haboush assisting a medic treating a casualty.

Robert Capa, “Untitled (Medics at Omaha Beach, June 6, 1944).” Annotated screenshot from magnumphotos.com. Victor Haboush indicated by red arrow.

The fourth witness to Capa’s presence on LCI(L)-94 was U.S. Coast Guard Chief Photographer’s Mate David T. Ruley. Ruley, a Coast Guard cinematographer assigned to film the invasion from the vantage point of this vessel, coincidentally documented its arrival at the very same spot at which Capa landed, recording the same scene from a perspective slightly different from Capa’s at approximately the same time Capa made his ten exposures.

Robert Capa, “The Face in the Surf” (l); David Ruley, frame from D-Day film (r)

Ruley’s color footage appears frequently in D-Day documentaries. Charles Herrick and I verified that these film clips described conditions at that same sector of Easy Red while Capa was there. Ruley’s name on his slateboard at the start of several clips enabled us to learn a bit more about him and his assignment.

Robert Capa, center rear, aboard LCVP from USS Samuel Chase, with camera during transfer of casualty, D-Day, frame from film by David T. Ruley

Most importantly, this resulted in the discovery of brief glimpses of Capa himself, holding Ruley’s slateboard in one scene and photographing the offloading of a casualty from LCI(L)-94 to another vessel in the second clip. These are the only known film or still images of Capa on D-Day, the only film images of him in any combat situation, and among the few known color film clips of him.

Robert Capa holding cinematographer’s slate aboard LCI(L)-94, D-Day, frame from film by David T. Ruley

Cinematographer David T. Ruley, illustrations for first-person account of D-Day experiences, Movie Makers magazine, 6/1/45

By noon the battle there was largely over, and Capa had missed most of it.

He made the return trip to England aboard the U.S.S. Samuel Chase.

Arriving back in Weymouth on the morning of June 7, Capa had to wait for the offloading of wounded from the Chase before he got ashore sometime around 1 p.m. He sent all his film via courier to picture editor John Morris at LIFE’s London office, instead of carrying it himself to ensure its safe delivery and thus enable Morris to face with confidence the imminent, absolute deadline of 9 a.m. on June 8.

As a result, Capa’s films did not reach the London office till 9 p.m. that night, putting Morris and the darkroom staff in crisis mode.

Capa’s shipment included substantial pre-invasion reportage of the troops boarding and crossing the English Channel, his skimpy coverage of the battle on Omaha Beach, and several images of the beach seen from a distance, made while departing on LCI(L)-94, as well as photos of medics tending to the wounded on the return trip aboard the Chase.

In addition to several rolls of 120 film, and a few 4×5″ negatives made on shipboard with a borrowed Speed Graphic, Capa sent Morris at least five rolls of 35mm film, and possibly a sixth.

These include two rolls made while boarding and on deck in the daytime, two more of a below-decks briefing, a (missing) roll of images made on deck at twilight during the crossing, and the ten Omaha Beach exposures, plus four sheets of sketchy handwritten caption notes.

All of these films — including all of Capa’s Omaha Beach negatives — got processed normally, without incident. The surviving negatives, housed in the Capa Archive at ICP, show no sign of heat damage. Thus no darkroom disaster occurred, no D-Day images got lost … and none got “saved” or “salvaged.”

In his memoir, Capa wrote that by the time he got back to Omaha Beach on June 8 and joined his press corps colleagues, “I had been reported dead by a sergeant who had seen my body floating on the water with my cameras around my neck. I had been missing for forty-eight hours, my death had become official, and my obituaries had just been released by the censor.” No correspondent has ever corroborated that story. No such obituary ever saw print (as it surely would have), no copy thereof has ever surfaced, and no record of it exists in the censors’ logs. Purest fiction, meant for the silver screen.

So much for the myth.

We learned a few other things along the way:

LIFE magazine ran the best five of Capa’s ten 35mm Omaha Beach images in the D-Day issue, datelined June 19, 1944, which hit the newsstands on June 12. (The other five were all mediocre variants of the ones they published.)

“Beachheads of Normandy,” LIFE magazine feature on D-Day with Robert Capa photos, June 19, 1944, p. 25 (detail)

The accompanying story claimed that “As he waded out to get aboard [LCI(L)-94, Capa’s] cameras got thoroughly soaked. By some miracle, one of them was not too badly damaged and he was able to keep making pictures.” That wasn’t true, of course. Capa returned immediately to Normandy, landing back there on June 8 and continuing to use the same undamaged equipment with which he’d started out.

No sheet of caption notes for Capa’s ten Omaha Beach images in Capa’s own hand exists in the International Center of Photography’s Capa Archive. Presumably he provided none. Morris himself must have provided some — drafted hastily on the night of June 7 — for both the set that he sent to LIFE and the set that he provided to the press pool; that was required of him by his employer and by the pool. As for the captions that appeared with Capa’s pictures in the June 19 issue, Richard Whelan writes, “Dennis Flanagan, the assistant associate editor who wrote the captions and text that accompanied Capa’s images in LIFE, recalls that he depended on the New York Times for background information, and for specifics he interpreted what he saw in the photographs.”

Thus the wildly inaccurate captions that (to use Roland Barthes’s term) “anchor” Capa’s images in LIFE’s D-Day issue, and on which most subsequent republications of these images rely, either got revised from John Morris’s last-minute inventions in London or written entirely from scratch by someone in the New York office, even further removed from the action.

LIFE’s captions indicated that the soldiers seen gathered around the obstacles were hiding from enemy fire. That was also untrue. Instead, we discovered that their insignias identify them as members of Combined Demolitions Unit 10, part of the Engineer Special Task Force, busy at their assigned task of blowing up the obstacles planted in the surf by the Germans in order to clear lanes for the incoming landing craft, so that they could deposit more troops and materiel on the beachhead.

Robert Capa, D-Day negative 35, detail, annotated

The demolition team that cleared this section of Omaha Beach, Easy Red, had more success than all the other demolition teams combined. In many ways, they saved the day for the Allies — at a high cost: these engineers as a group suffered the highest casualty rate of any class of troops on Omaha Beach. Capa’s failure to provide caption notes for these exposures resulted in 70 years of misidentification of these heroic engineers as terrified assault troops pinned down and hiding behind those “hedgehogs.”

We learned that ICP had a habit of obstructing any research into the life and work of Robert Capa that did not conform to Cornell Capa’s and Richard Whelan’s censorious requirements. ICP refused to allow British military historian Alex Kershaw to access any of the materials in the Capa Archive, and refused to grant his publishers permission to reproduce any Capa images in his unauthorized biography, published in 2002. ICP also refused to allow French documentary filmmaker Patrick Jeudy to use any of the primary Capa materials they controlled in his remarkable 2004 film, Robert Capa, l’homme qui voulait croire à sa légende (“Robert Capa: The Man Who Believed His Own Legend”). Upon the film’s release, Cornell Capa persuaded John Morris to sue Jeudy in France, in an unsuccessful attempt to block its distribution.

Robert Capa, “ruined” frames from D-Day, June 6, 1944. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

We also discovered that TIME Inc. had authorized the creation of unlabelled digital fakes of Capa’s supposedly “ruined” and discarded Omaha Beach negatives, for insertion into that May 2014 video commissioned from Magnum in Motion, the multimedia division of Magnum Photos, to celebrate the 70th anniversary of D-Day. Our disclosure of this deception forced TIME to acknowledge the fakery and revise that video overnight.

Richard Whelan, “Robert Capa: In Love and War” (2003), screenshot

Finally, we discovered that Capa’s authorized biographer, the late Richard Whelan, lied outright about the emulsion sliding on Capa’s D-Day negatives (among other things). And Cynthia Young, his successor as curator of the Capa Archive at the International Center of Photography, not only repeated his lie but plagiarized it in a 2013 text of her own.

Cynthia Young, “The Story Behind Robert Capa’s Pictures of D-Day,” June 6, 2013, screenshot from ICP website 2014–06–12 at 11.38.23 AM

Many of Capa’s rolls of film from the 1940s — and not just those he made on D-Day — show the exposure overlapping the sprocket holes. This resulted from a mismatch between Kodak 35mm film cassettes and the design of the Contax II, the camera Capa used that day, and not from any damage to the films.

Top: Contax camera loaded with shorter Kodak cassette showing sprocket holes being exposed. Bottom: Capa negative shown with proper orientation as it would have appeared in the camera. Note exposed sprocket holes. Top photo © 2015 by Rob McElroy.

Since the Capa Archive at ICP houses all those negatives and their contact sheets, both Whelan and Young have known this all along. Given the official position that first Whelan and now Young have occupied at ICP, they are de facto the world’s foremost authorities on Robert Capa. As such they represent, with regrettable accuracy, the deplorable condition of Capa scholarship in our time.

Cynthia Young, “Morning Joe,” MSNBC, 6–13–14, screenshot

The myth of Capa’s D-Day and the fate of his Omaha Beach negatives falls apart as soon as one compares its narrative to the military documentation of that epic battle. It collapses entirely when one examines closely the physical evidence — those photographs and their negatives.

The promulgation of that myth by the Capa Consortium, all of whose members have a vested financial and public-relations interest in furthering the myth, has proved itself calculated, systematic, duplicitous, and self-serving. Its voluntary dissemination by others, including reputable scholars and journalists, has shown those authors as lazy, careless, and professionally irresponsible. The Capa D-Day myth serves as a classic example of the genesis and evolution of a falsified version of history that, with its emphasis on the exploits of individual actors, distracts us from paying attention to the machinations of the corporate structures through which information must pass and get filtered before reaching the public — powerful institutions with agendas of their own.

I would like to think we have made a sufficiently convincing case that no one can credibly tell the standard Capa D-Day story again, at least not without acknowledging our contrary narrative. After all, our investigation forced a reluctant John Morris, the most energetic and vocal proponent of the legend, to recant its central components on Christiane Amanpour’s CNN show in the fall of 2014.

Most recently, in a Lensblog piece published in the New York Times on December 6, 2016 — just a day before his 100th birthday, and months before his death in Paris in July 2017 — Morris once again admitted that he’d never actually seen any heat-damaged 35mm negatives; that Capa may have only made the ten surviving images; and that he may have stayed on Omaha Beach only long enough to make them.

As for the institutions involved in perpetuating the myth: On June 6, 2016, ICP published this post on the institution’s Facebook page: “During the D-Day landing at Omaha beach, Robert Capa shot four rolls of 35mm film — only 11 frames survived. By accident, a darkroom worker in London ruined the majority of the film.” Since then, grudgingly, as a result of my public prodding, ICP has begun at last to make available to researchers the papers of Cornell Capa, promising to also permit access sometime in the near future to the papers of Richard Whelan, along with the Jozefa Stuart interviews from the early 1960s on which Whelan based much of his work.

Yet, as recently as October 2018, Cynthia Young published this statement in a special issue of the French newspaper Le Monde: “Capa, surrounded by explosions of bombs and bursts of machine guns, took photos in the water for a short while. … He expected his films to have been damaged by the water — he was squatting in the sea, troubled and agitated, tinged with blood. A few weeks later, he learned that all but ten images had been destroyed in the darkroom or during the shooting.” (My translation — A.D.C.).