#alternativemanga

Text

The Heta-Uma Appeal

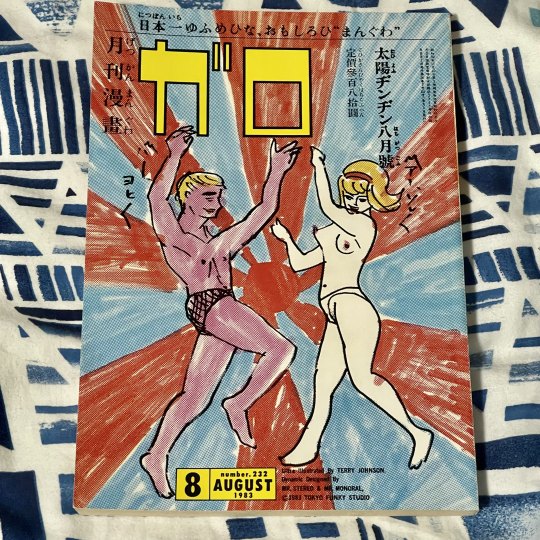

Garo 1982 September Issue with cover art by Yumura Teruhiko

Heta-uma. 'Heta' as in 'bad', 'umai' as in 'good'. Not officially recognised as an art movement, the wave of manga/art/illustrations that kicked off in the 70s were seen as being "so bad it's good". There are a number of different ways to describe heta-uma, with terms like "unskilled" and "ugly" being used to categorise the rough look of the art. Check out this highly detailed and informative article from Sabukaru for more on its history!

If you're wondering who pioneered the craze and led the charge, look no further than three artists deemed to be the most influential and notable: Yumura Teruhiko, Ebisu Yoshikazu and Takashi Nemoto. Garo was a platform that allowed these artists to spread the name and fame of their crude and raw drawings, often featuring gritty and vulgar subject matter. Heta-uma is a style that rejects the norm and pushes outside the box for new ways of expression, going against standards to evoke new reactions in readers. It aims to leave you laughing, gagging in disgust and everything in between with its sheer variety of storytelling. You can find gag manga, comedic shorts and satire. You can find political and social commentary veiled underneath raw and seemingly shallow drawings. It's a style that I honestly took me awhile to get into, but my appreciation slowly began to accelerate as I dived into alternative manga, especially mangaka like Ebisu.

Ebisu Yoshikazu: First Exposure

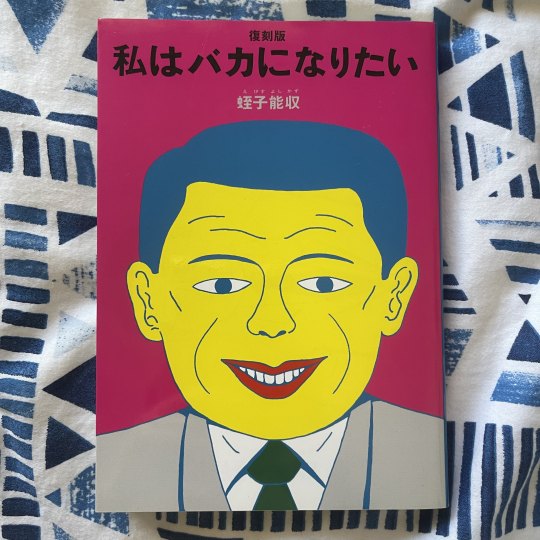

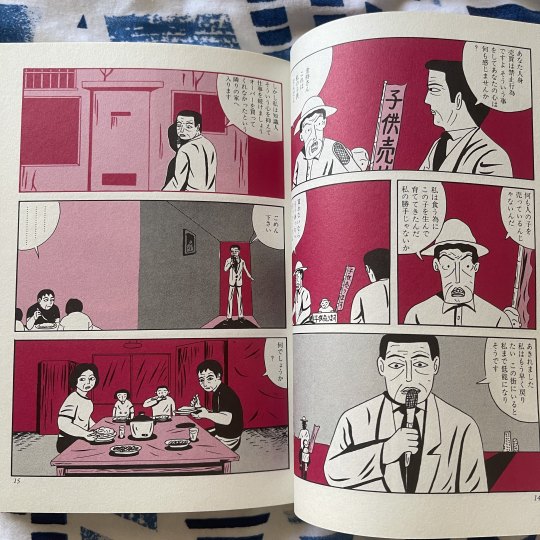

My very first read from Ebisu was a book titled "I Wish I Was Stupid" (Watashi wa Baka ni Naritai), now being released in English by Breakdown Press, an extremely exciting occasion for alternative manga fans. As far as I know, there are few heta-uma mangaka with an official English book, one being Hanakuma Yuusaku with his "Tokyo Zombie" published by Last Gasp in 2008. Takashi Nemoto also had his "Monster Men: Bureiko Lullaby" published in English by Picture Box in 2008. At the moment, Ebisu's "The Pits of Hell" by Breakdown Press is also being reprinted, so I'd hope that demand is high enough for more heta-uma exposure to the English market. There are also alternative manga anthologies like "Ax (Vol 1): A Collection of Alternative Manga", "Sake Jock", and "Comics Underground Japan" that feature heta-uma mangaka and artists like Suzy Amakane and Carol Shimoda amongst others.

But back to Ebisu. I was again exposed to his works via a haul video by Shawn from Japan Book Hunter, and the cover of the manga was enough to get me interested. The book is raw, disgusting, incredibly vulgar and in-your-face with its crazy drawings on confronting subject matter. It blends dark humour with satire on Japanese society extremely well, all supported by rudimentary character designs of salarymen, housewives and naïve children. I loved the weirdly random and surreal settings that feature UFOs flying in the sky, coupled with the desolate backgrounds that emphasise the other-worldliness of Ebisu's work. Its content is extreme, and it left such a lasting impression on me that I had to explore further into the world of heta-uma. I picked up "The Pits of Hell" after that, and am definitely planning to get more Ebisu books in the future.

AX Magazine: A Bigger Picture

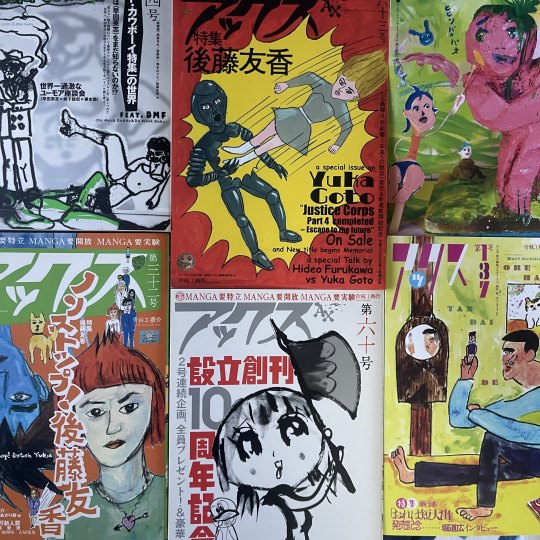

Assorted AX issues featuring heta-uma artists Takashi Nemoto, Goto Yuka, Shiriagari Kotobuki, Family Restaurant and Hori Michihiro

After discovering Ebisu, I had bought myself a whole stack of AX issues, opening up a whole new world of more contemporary heta-uma. This is where I became addicted to artists like Goto Yuka, Shiriagari Kotobuki and Family Restaurant, all centred on more a more comedic/gag style of manga. I still have a long way to go in terms of reading up on all the wonderful heta-uma out there, so I would say I'm still only on the first couple of steps in. One of my favourite heta-uma works that I'm still reading at the moment is Goto's "Justice Corps" (Seigitai), a gag manga following a group of vigilantes fighting to protect the city from monsters and villains. It's a pretty simple premise, but the slapstick humour combined with very rudimentary drawings gives off a nostalgic kids-show vibe. Addicting, straightforward and fun.

Justice Corps vol 1 by Goto Yuka

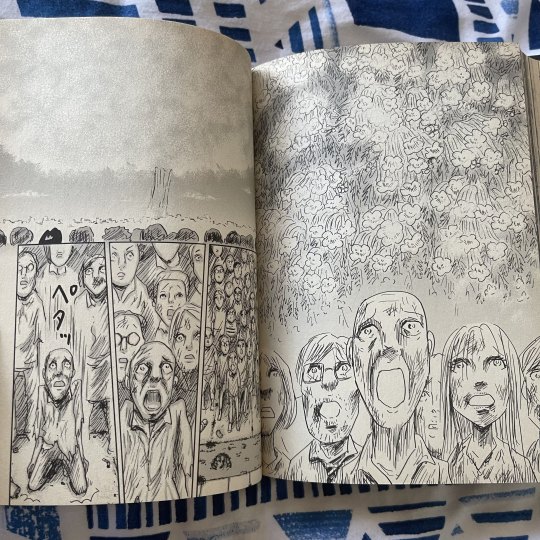

Shiriagari's "Jacaranda" is another amazing story that follows the violent and chaotic destruction of a city and its subsequent rebirth. The manga begins with a woman on a train brutally beating an old man for accidentally leaning on her shoulder as he struggles to stay awake. Nobody tries to do anything to help, a common critique of passivity in Japanese society that you can find in lots of other manga. Over the course of the story, the city is ravaged by a giant Jacaranda tree that sprouts and destroys the entire landscape, massacring the people around it as buildings topple and fires burn. The art is intense and the civilian deaths are brutally depicted through most of the book. Though, the end result is that of a blooming Jacaranda tree that towers over the city, hailed and prayed to by the survivors. There is little dialogue with most of the sound dominated by screams and onomatopoeia, but Shiriagari's raw and rough art style very much lends to a violent story like this. You can interpret the narrative in many ways, with one observing the first event of the woman's violence on the train as a karmic catalyst to the Jacaranda sprouting. This book is a good example of how the heta-uma style can also lean towards quite sincere and more serious works, a great display of versatility.

Jacaranda by Shiragari Kotobuki

Although, I must say that not every heta-uma work I've read is a favourite for me. "Jacaranda" is, in my opinion, an amazingly raw and hard-hitting work, but Shiragari's "Twin Adults" (Futago no Oyaji) series is very much a hit or miss. You can find individual chapters throughout many of AX's early issues, and there are also tankobons that collect all the stories into one book. The series features two twins arguing and playing, both up to whatever antics they may be up to, but not many of them land for me personally. On a different topic, Takashi Nemoto's subject matter is also a bit too raunchy for my tastes. I appreciate his art style as a whole and actually really love some of art that don't feature extremely explicit imagery, but the usual abundance of the dirty stuff isn't for me.

Left: Takashi Nemoto page from Garo 1983 April / Right: "Futago no Oyaji" from AX vol 8

The King Terry Obsession: Present Time

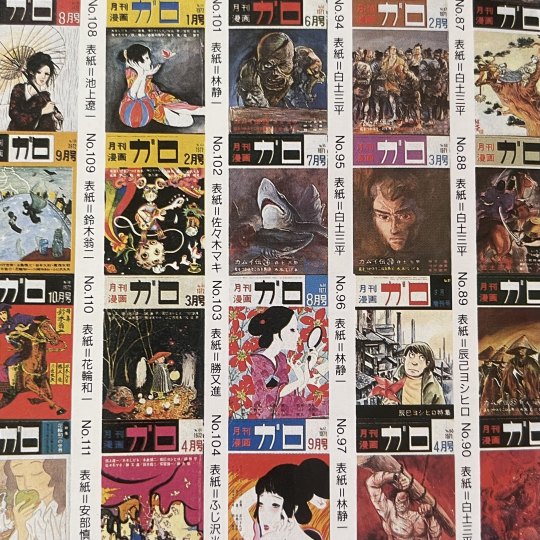

Various 1983 Garo issues featuring cover art by Yumura Teruhiko

Yumura Teruhiko. King Terry. Terry Johnson. Flamingo Terry. My current artist obsession. The artist is a man of many names. King Terry is attributed as the founder and pioneer of the heta-uma movement from the 70s and onwards with his "artfully artless" illustrations, a quote from Ryan Holmberg which I find is an extremely fitting description. You can find his article below!

King Terry mainly drew illustrations and has only put out one manga in his career, "Penguin Rice", where he drew the art for a story written by Itoi Shigesato for Garo in 1976. I haven't found a copy of it yet, but my eyes are always on the lookout for it. But for now, I'm satisfied with the various Garo issues he'd illustrated covers for, all of them addicting to look at. Yumura had illustrated all the covers for Garo's 1977 issues, reappearing and staying as the physical face of the magazine from 1982-87. He's an artist that has grown on me over time, and I can't give a clear reason why, but it's very much tied in with my love for alternative manga.

And that's pretty much my experience with the wonderful world of heta-uma. To conclude, I want to have one last section about an event that I feel was an extremely important one for heta-uma and alternative manga fans outside of Japan.

Heta-Uma Mangaro: Le Dernier Cri Exhibition

Le Dernier Cri, a French publishing house headed by Pakito Bolino, is your one-stop destination for underground and alternative art that thrives outside of the mainstream. They sell high quality silkscreen prints, books and posters from many Japanese artists and mangaka, many of whom I've talked about before. In 2014, Bolino and Taco Che owner Ayumi Nakayama curated an extensive collection of works from Japanese artists in the double exhibition "Heta-uma Mangaro", a gallery of 40 years of Garo and heta-uma history. There was a catalogue book released for the event that is long OOP, but I'm still patiently waiting for one to pop up sometime soon. But having such a large event specifically for alternative manga and heta-uma is an amazing feat that I hope will inspire bigger and more frequent exhibitions like these. Thanks for reading!

#manga#hetauma#alternativemanga#manga recommendation#art review#manga art#manga panel#japanese culture#japanese history#contemporaryart

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

U.D.W.F.G. presents: Daisuke Ichiba

.

.

.

Hollow Press, September 2019

#daisukeichiba #manga #comics #alternativemanga

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

One with the Cow

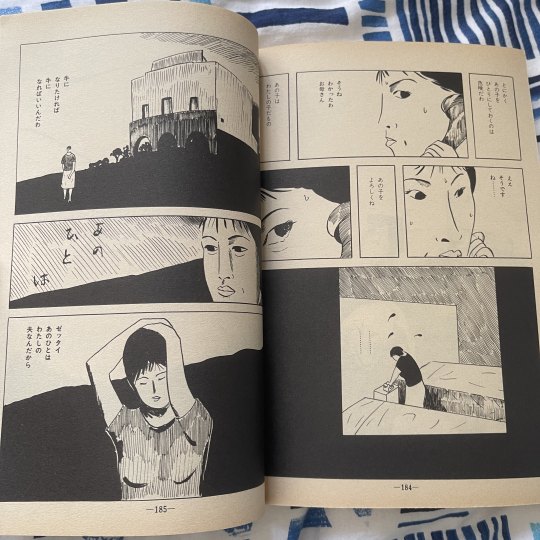

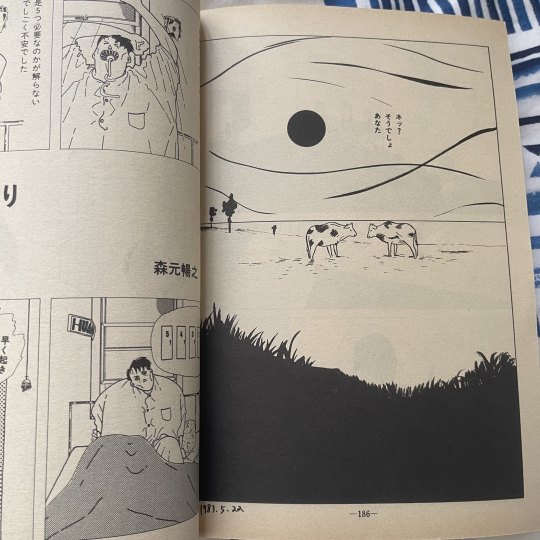

Garo 1983 August issue with cover art by King Terry/Landscape with Cows cover page

At no point in my reading journey would I have expected to read such a compelling story that intertwined identity and cows so seamlessly. And no, they're not separable. The two work hand in hand to open my eyes to such an expressive and unique style of storytelling.

The story in question is Kanno Osamu's "Ushi no iru Fuukei" (The Landscape with Cows) from Garo. There isn't too much info on Kanno that I personally could find, but he had debuted in Yagyo in 1973 and has published works in a few other magazines mainly in the 70s and 80s. Currently, he's serialising his "Meshia no Umi" (The Sea of the Messiah) series in AX, with the most recent issue at this current date (vol 154) including its 66th chapter. His style can be traced back to the dreamlike and surreal storytelling of gekiga greats like Hayashi Seiichi and Tsuge Yoshiharu. Those two mangaka are cited as his inspirations, but other mangaka that have styles along the same vein also include Abe Shinichi and Oji Suzuki (for those who are curious for more). With Garo, I've been exposed to a wide variety of amazing artists and stories, but "The Landscape with Cows" is one of the best one-shots I've read so far from this magazine.

Neurosis?

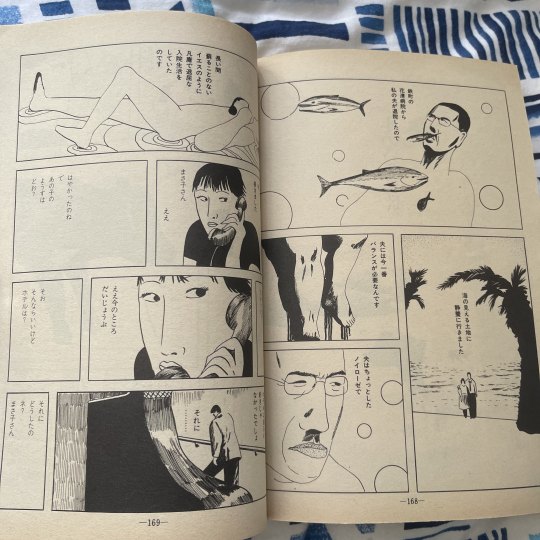

Our story begins with our narrator Masako calling her mother-in-law on the phone to update her on her son. Masako's husband had recently been discharged from the hospital for a case of neurosis after he had sent some concerning letters to his parents. They're currently staying at a hotel near a beach as he recovers, but something interesting about the location is its abundance of cows. Masako thinks that maybe it could be a tourist attraction, but also that they look visually off-putting to her.

"[The cows are] kind of grotesque aren't they."

She assures her mother-in-law over the phone that all is well with her husband. The mother is quite over-worried and anxious, an overly protective parent. We never get to see what the mother looks like, but it's quite clear that she's being a bit of a handful with her check-ups.

Right after the first four pages, Kanno shows a strange scene of the husband naked, bending over and making cow noises with 'horns' attached to his head.

"That time, when I looked into his eyes, I was speechless"

Masako recounts her experience seeing her husband in this strange position. She also reveals that she always knew her husband was gay and that his love for her was never true. In the background, a giant dinosaur looms, very reminiscent of Oji Suzuki's surreal gekiga style. I am incredibly in love with this characteristic seen in gekiga frequently: seemingly random placements of objects that make the story's atmosphere extremely mysterious and reflective.

Various panels from Oji Suzuki's 'Motorbike Girl' tankobon

Cows Over Humans

Masako's mother-in-law continues to ask her to take care of her son, this time expressing that she's scared of him taking his own life. But Masako thinks to herself that it might be something different:

"I don't think he's thinking about killing himself. I think it's that he wants to be reborn as a cow after dying."

This line is such an interesting one to think about. Coupled with the ominous imagery, especially the panel with his head being that of a cow, you wonder about what it is about bovines that appeal to the husband. Or, maybe you're not supposed to know. The way that Kanno depicts the husband's obsession doesn't put it down and merely just treats it as just another way of thinking, another belief or worldview that anyone can have. It's especially made apparent when Masako starts reassuring her mother-in-law about the contents of her husband's letter:

"What he said about cows being better than people is wrong. Isn't that right, mum."

On this page, what follows Masako's line are panels of random people with words like famine, culture, disease, and pretty much any human concept/idea/issue that exists. These examples contradict what Masako is saying on the phone, and shows that her husband might be right in saying that cows are better than humans after all. His mum can be representative of those who can't understand the sensibilities of people with different worldviews or beliefs, which I think plays out quite well with Masako being in the middle of all this. Her relationship with both mother and son gives her a unique perspective, and hence narration, on her husband's 'neurosis'. She has to assure that everything is okay for the worried mother, but also has to internalise the thoughts she has about her husband's true situation.

"Cows don't fight. They aren't dishonest like humans are."

So what is wrong with wanting to be a cow? They don't fight, they aren't corrupt or start wars or anything like that. They are simple creatures devoid of any worries other than their survival. Masako's line about dishonesty is ironic considering how she'd lied to her mother-in-law over the call. What the quote says to me is that Masako is fed up with having to put on an appearance to her in-law. She has to lie and assure her that everything is okay, but all of that can be such a chore. Which comes back to the point that I believe Kanno could be conveying: what's wrong with wanting to be a cow? What's wrong with wanting to be free from human flaws?

This thought process I have with what Kanno could possibly be trying to say brings me back to Tsuge Yoshiharu's "The Incident at Nishibeta Village", which follows a village's hunt for a man who had 'escaped' the sanatorium. Though, when we do encounter the escapee, he doesn't seem as crazy or violent as the villagers make him out to be. That clash between the man and the rest of the villagers is quite similar to this situation with the husband and his mum. Is he as crazy or suicidal as she thinks he is? Doesn't seem like it from the way Kanno depicts him.

Tsuge Yoshiharu's "The Incident at Nishibeta Village" - taken from Tom Gill's article in the Asia-Pacific Journal

The way this story progresses points more and more towards the husband's desire being something that is normal. He may be judged on the outside by those who don't know him well, that being his mum in this case. But for those who do understand him, that being Masako, they can understand where he is coming from and why his desires aren't so outrageous. The husband's neurosis and the duality of how its perceived by others is such an interesting topic that really makes the cow imagery natural to the story.

At the end of the story, Masako continues to voice her thoughts through the narration.

"If he wants to be a cow, then be a cow. That person will still always be my husband. Isn't that right, you?"

Here, this last section of dialogue is Masako expressing her views on her husband's situation. It's a confirmation that she doesn't view the desire as negatively as his mother. There could also be a hint of jealousy in her with how she has deal with the over-protective parent. Her husband doesn't have to worry about these trivial things. Living in bliss, no matter the form, is living in bliss. It doesn't matter if you want to be a cow or anything else. The husband is in a state of bliss that is impenetrable by human worries and concerns.

Final Thoughts

Kanno Osamu is a mangaka that I really want to read more from, but his tankobons are quite hard to find. "The Landscape with Cows" was my first exposure to him and reinforced what I love about gekiga. As I had mentioned before, other mangaka like Hayashi Seiichi, Oji Suzuki and Abe Shinichi all have similar styles in storytelling. They are mysterious in the way they depict characters and settings, oftentimes placing seemingly random panels and objects throughout their narratives. What draws me the most to their works is the atmosphere, one that I think is quite unique to Japanese artists and mangaka. One of my favourite books, "Almost Transparent Blue" by Ryu Murakami, also gives off the same tone as a lot of gekiga. Their stories are about people getting by, wanting to escape from the world to live in bliss, unconcerned about wars, careers, relationships and the future in general. With this story by Kanno, it pretty much says the same thing. What is wrong with wanting to be free? If you want to be a cow, so be it. It's a normal desire to have, no matter what form it may manifest in. Legendary short story in my opinion, one of my favourites from Garo.

Thanks for reading!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Journey with Garo

Extract of Garo issue cover art from the Garo Mandala (1991)

It must've been near the end of 2022 when I discovered the treasure trove that is the Monthly Manga Garo, a legendary alternative manga magazine that ran from 1964 to 2002 that thrived against the backdrop of a politically turbulent post-war Japan. In the English market now, we're fortunate enough to be getting a wide variety of translated works from some of the manga greats who had serialised in Garo. From pillars like Tsuge Yoshiharu and Shirato Sanpei to the heta-uma king Ebisu Yoshikazu, you won't ever be bored with the sheer variety of stories, art styles and subject matter that can be seen throughout Garo's lifetime. Pick up any issue and you'll be surprised as to how many types of stories will grace your eyes.

Now back to my personal experience with Garo. I had seen a Garo issue for the very first time through one of Shawn's videos from Japan Book Hunter, a manga plug that I've used for amazing and rare manga that you won't be able to find anywhere except in Japan's jungle of bookstores. His YouTube channel at the time was uploading extremely interesting manga hauls that touched upon a wide variety of lesser-known genres and niches in Japanese comics. There were alternative manga, Shoujo horror, SF, gag and all the other gritty stuff from the wider world of manga outside the usual Shounen Jump. I watched his channel religiously and still look back on some videos to this day, reflecting on how far I've come in learning about manga and manga history. Huge shoutout to Shawn and his store, check him out!

After moving away from the more well-known Seinen and Shounen titles in search of more to explore, my foray into alternative and underground manga was one of the most enlightening experiences in my reading journey. I'd equate my discovery of Garo to my first reads of Borge's short stories, both mind-blowing experiences that have completely transformed my tastes in fiction forever. Garo and my subsequent dives into other alternative manga have now created an insatiable curiosity into what else could be hidden out there in the largely untranslated world of manga. It seems like going backwards in time is the direction I'm taking, but I haven't even scraped the tip of the iceberg yet with Garo, let alone other niches like Shoujo horror and Kashihon. Slowly I'm completing issue after issue, gradually exposing myself to a legendary group of mangaka and artists that have cemented themselves in a magazine that I feel stands the test of time.

At this moment, I have about 40-ish Garo issues on my shelves, and I've read maybe 15 of those. It's a slow reading process, but it's insanely worth it. Each decade is vastly different from the others, so it's extremely fascinating to see the evolution of the magazine over time. For example, starting off in the 60s you have the legendary Kamui-den by Shirato Sanpei, a ninja tale set in feudal Japan that involves social/political commentary on topics like class conflict and oppression. The series was responsible for the birth of Garo because founder Katsuichi Nagai, who I believe was already experienced in the kashihon market, had wanted to give a platform for Shirato to serialize his work. Many stories in the 60s era of Garo were more politically expressive, coinciding with a lot of the unstable politics at the time in Japan. Other mangaka largely present throughout 60s Garo include Mizuki Shigeru, Tsuge Yoshiharu, Nagashima Shinji, Takita Yuu, Tsurita Kuniko and many more.

Various Garo issues from my bookshelf

Then, you move into the 70s. This is where mangaka and artists like Hayashi Seiichi, Tsuge Tadao, Susumu Katsuma and Abe Shinichi start to become more present in the spotlight and appear more frequently in issues. A more surreal and weirder style of stories begin to appear in this decade, marking a key period for Gekiga in my opinion. Personally, when I think Gekiga, my mind goes to people like Hayashi, Tatsumi, Tsuge and Abe, so it's a time that I feel was a very important one for Garo.

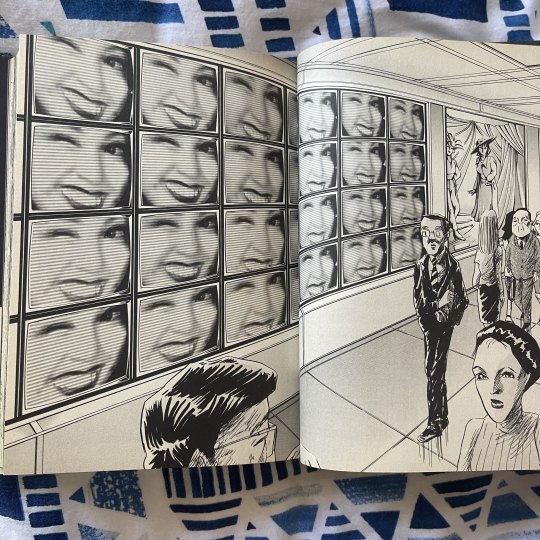

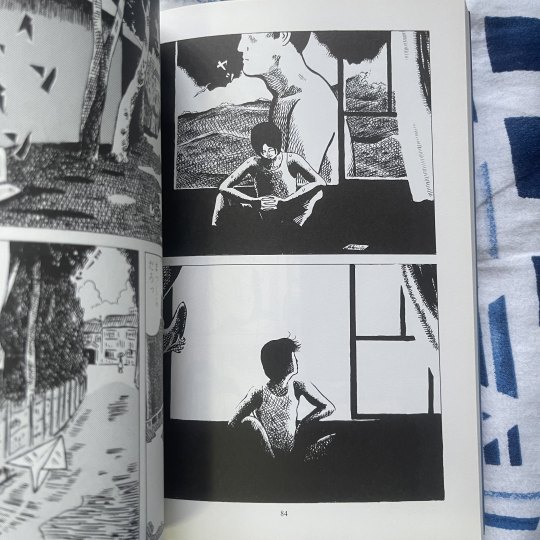

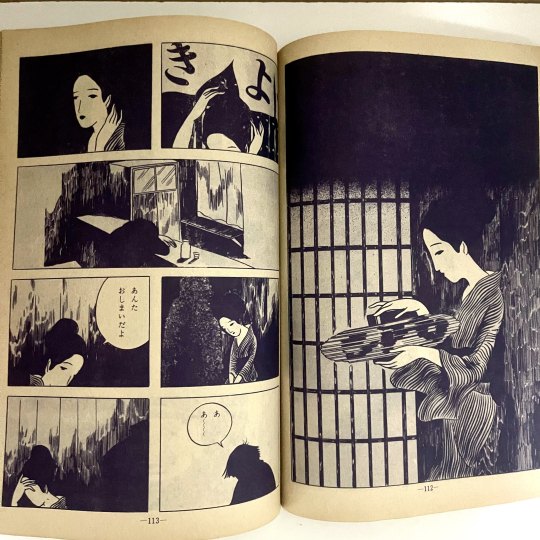

Flowering Harbour - Hayashi Seiichi (Garo 1969 May)

The majority of my Garo reads have been towards the tail end of the 60s, with some reads spread throughout the 70s and 90s. Funnily enough, I don't think I have many issues from the 80s. From what I've read from the later decades of Garo though, I've fallen deeply in love. Going from the Tsuges, Hayashis and Mizukis to a whole new world of more contemporary mangaka like Usamaru Furuya, Kawai Katsuo and Maruo Suehiro opened up an even bigger obsession for the magazine. You have an influx of ero-guro (erotic-grotesque) and heta-uma (bad-good) in the scene that introduced a great deal of new names, a lot of whom had also continued into Ax magazine, the spiritual successor to Garo, after the magazine's end. I can make a whole other post on Ax, but that's for another day.

My Youth - Maruo Suehiro (Garo 1983 August)

That about sums up my journey reading Garo from discovery to this current point in time. With 426 issues spanning from the 60s to the early 2000s, I'm not going to run out of issues to read anytime soon. Maybe in a future post, I'll talk more in-depth about specific mangaka and artists that I enjoy. But anyways, thanks for reading my first blog post if you've come this far! Hoping to get out more posts in the future because it really scratches an itch for me when I can express all my thoughts like this in an extended post format.

3 notes

·

View notes