#historian: virginia k henderson

Text

Quite apart from its political implications as an identifying emblem for the Tudors, the rose was an important and pervasive Marian and Christological symbol that was used throughout the Middle Ages. Although in a religious context its significance was multi-layered and thus sometimes convoluted, basically the rose was used to refer either to specific qualities of the Virgin or to the Virgin herself and to the Passion of Christ. It is especially relevant, therefore, with regard to the derivation and rationale of the Tudor device of the rose, that both the Virgin and the Passion of Christ were central to Henry VII's personal devotions, as his will clearly indicates and the imagery of his chapel demonstrates. Thus, unquestionably, beyond its dynastic use, the rose would have had significance for him personally in its capacity as both a Marian and Christological symbol.

— Virginia K. Henderson, Retrieving the "Crown in the Hawthorn Bush": The Origins of The Badges of Henry VII | Traditions and transformations in late medieval England

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the victor at the Battle of Bosworth, in fact, Henry VII would have had special reason to honour the Virgin and adopt her symbol of the rose, for it was during the octave of the Assumption of the Virgin from 15 August to 22 August in 1485 that his fortunes turned so dramatically after his fourteen years of exile in Brittany. It was within that eight-day period that vital supporters joined his forces as he made his way across Wales, entered England near Shrewsbury, and advanced south-eastward to his victory at Bosworth Field. On 22 August, the final day of the octave, the crown was his.

— Virginia K. Henderson, Retrieving the "Crown in the Hawthorn Bush": The Origins of The Badges of Henry VII | Traditions and transformations in late medieval England

To judge by the several documents that record Henry Tudor's presence at mass while he was in exile in Vannes, all of which occurred on the feast days of the Virgin, he appears to have been devoted to her prior to his entry into England. That would not have been unusual in Brittany, however, where devotion to the fiercely debated concept of the Immaculate Conception was especially strong in the fifteenth century and where undoubtedly, as has been argued elsewhere, the future king was under the tutelage of the Observant Franciscans, who were ardent supporters of the Virgin and her immaculacy.

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The magnitude and complexity of Henry VII’s provisions for masses and prayers to be said following his death have occasioned numerous comments about his presumed guilty conscience, his alleged need for restitution for his Machiavellian ways, and his calculated attempt to purchase salvation [...] In addition to the funeral masses, Henry VII also paid for masses to be said for his health and soul and for those of his family since the beginning of his reign; and in at least the last three years of his life, he paid for ten thousand or more masses each Lenten season [...] Henry VII’s requests for prayers and masses were huge, constant, and costly, certainly an outlay that would not seem a likely choice for a more worldly king with secular objectives in mind, but one that comfortably fits an individual who is decidedly more devout. They assuredly suggest someone whose beliefs were closely aligned with the thinking of late medieval affective piety.

Virginia K. Henderson, “Rethinking Henry VII: The Man and His Piety in the Context of the Observant Franciscans” In: Reputation and Representation in Fifteenth-Century Europe (2004)

#henry vii#in honour of his deathday ♥#historian: virginia k henderson#reputation and representation in the fifteenth-century england

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The unusual course that Henry Tudor’s life took from his birth until his ascension to the crown made him ripe for deep-seated spiritual conviction. By any measure, it is a miracle that he became king, and it would have been most natural in the fifteenth century, particularly given the medieval propensity to interpret historical events as the working out of God’s intention, to attribute his survival and rise to power to God’s hand.

More than likely also, his experiences in exile contributed to the development of Henry VII’s image of himself as providentially guided. Both the inclination to interpret events in terms of sacred history and the redeemer-hero legend of Cadwaladr, which was popular not only in Wales but also in Brittany, certainly would have encouraged that perception. Whether he waited for the Welsh poets to cast him in the role of the redeemer-hero with the rise of Richard III, or he cast himself in that role to give meaning to his exile, clearly the legendary prophecy presented the potential to instill the notion of a prince as Christ-like. It would have been but a small step from there to interpret his exile anagogically as a form of preparation through trial and suffering that was analogous to the trials of Christ, especially if he were guided by the Observant Franciscans, for whom the imitatio christi and via crucis were so important.

Furthermore, it was during the octave of the Assumption of the Virgin from 15 August to 22 August in 1485 that the fortunes of Henry Tudor turned so dramatically after fourteen years of exile in Brittany. It was within that eight-day period that vital supporters joined his forces as he made his way across Wales, entered England near Shrewsbury, and advanced southeastward to his victory at Bosworth Field. More significantly still, it was on the final day of the octave, that of the Coronation of the Virgin, that Henry VII won his crown. However fortuitous it might be judged today, surely then the coincidence of the divine and royal coronations would have been interpreted as a sign of divine sanction.

Moreover, the victory would have been attributed to the intercession of the Virgin. Following the tradition of medieval devotional practice and influenced by Franciscan teachings, no doubt Henry VII would have considered himself to have been under the special protection of the Virgin during his perilous journey, for he regarded her as the “surest refuge of all nedefull.” It was to her, he stated in his will, that “in al my necessities I have made my continuel refuge, and by whom I have hiderto in all myne adversities, ever had my special comforte and relief.” Indeed, given the whole range of improbable circumstances that surrounded his rise to power, it is not surprising that Henry VII declared his victory to have come about by “the right judgment of God,” however conventional that phrase might have been for others.

Indeed, it was his debt to divine grace that Henry VII sought to acknowledge in the silver-gilt statue of himself that he bequeathed to the shrine of Edward the Confessor in Westminster Abbey. The nearly life-size effigy of the king clothed in armor was to represent him kneeling and holding his crown. Far from the “audacious” and deliberately propagandistic image of him receiving his crown that Goodman and many others have claimed, the statue was intended to portray Henry VII returning his crown. It was to represent, according to his will, “the Crowne which it pleased God to give us, with the victorie of our Ennemye at our furst felde; the which Ymage and Crowne, we give and bequethe to Almighty God, our blessed Lady Saint Mary, and Saint Edward King and Confessour.”

The gesture of the statue, in fact, signified the relinquishing of Henry VII’s crown, the very symbol of his earthly identity, so that, by stripping himself of his earthly possessions and humbling himself before God as urged by St. Francis and the Observants, he could attain union with God and life eternal.

♕ Virginia K. Henderson, Rethinking Henry VII: The Man and His Piety in the Context of the Observant Franciscans

#to finish the celebrations 🌹#henry vii#battle of bosworth field#historian: virginia k henderson#reputation and representation in fifteenth-century europe

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Harley MS 1498, f.1 (British Library)

This manuscript preserves a series of four agreements (indentures) made on 16 July 1504 between Henry VII and the Abbot and monks of Westminster Abbey concerning the king’s new burial chapel. The folio contains full bar borders of red roses and gold portcullises, as well as England’s arms supported by Henry VII’s badges of the red dragon and white greyhound.

The beginning of the texts reads: ‘This indenture made betwebe the moost cristen and most excellent Prince kynge Henry the seventh by the grace of God Kyng of Englande and France and Lord of Ireland the xvi daye of July the vyntene yere of his moost noble reigne and John Islipp Abbot of the monastery of Saynt Petre of Westm. and the prioure and convent of the same monaster.’

An interesting fact about the document is that it was clearly written and illuminated before the actual date of signing, 16 July 1504, which was inserted in a different hand in a space that was left for that purpose. Virginia Henderson comments on the choice:

“Even the date on which the indentures that founded the chantry of Henry VII in the Lady Chapel were signed relates symbolically to [Henry VII]’s devotion to the Passion, his concern for the host, and his interest in the Five Wounds of Christ, to which a quarter of the masses to be said after his death were dedicated [...] It was on the sixteenth of July that the Feast of the Relics was celebrated at Westminster Abbey, where the most important and indeed very special relic was that of the Holy Blood, which Henry III had obtained for the abbey in 1247. It was on the sixteenth of July too, that St. Francis had been canonized in 1228, and thus it was a feast day for the Franciscans, as well. The selection of the date, therefore—which only could have occurred at Westminster, for the Feast of the Relics was celebrated on different days at different churches—honored two primary aspects of the king’s devotional interests. The choice of the date is far too subtle for someone trying to achieve only the appearance of piety, and one that is unlikely to have happened simply fortuitously, given Henry VII’s patronage of the reformed Franciscans.”

#henry vii#manuscript#1504#dailytudors#historian: virginia k henderson#reputation and representation in fifteenth-century europe

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some late night thoughts to wrap up my blogging about Henderson’s Rethinking Henry VII: The Man and His Piety in the Context of the Observant Franciscans.

Certainly one of the most notorious beliefs regarding Henry VII’s last will is his request for ten thousand masses to be said for his soul, which many historians have interpreted as ‘superstition’, ‘a conscience riddled with guilt’ or a ‘morbid obsession with the fate of his soul’. Henderson argues that those interpretations are jarringly misleading in the context of late medieval devotional practice: if Henry VII’s request exceeded the number of masses said for the soul of an English king ever since the times of Henry III, they were not at all unusual in England and much less abroad. For example, Cardinal Henry Beaufort, Henry VII’s great-granduncle, also requested ten thousand masses to be said for his soul, and William Courtenay, archbishop of Canterbury, requested fifteen thousand masses when he died.

A request for such a great number of masses was entirely normal in Brittany and France. Henderson mentions a 14th-century French testator, for example, that requested twenty-five thousand masses for his soul. Apparently, if you were a lesser noble in France in the late Middle Ages you would at least request for two to three thousand masses for the repose of your soul. “In this respect then,” Henderson comments, “Henry VII was following an accepted, if not common, practice in England, and one that may well have been inspired by his experiences abroad.”

It’s also important to consider that Henry VII paid for masses to be said for his and his family’s health and soul throughout the entirety of his reign, and in his last three years he paid for ten thousand or more masses to be sung each Lenten season. His conviction in the power of prayer can be seen in the charter he granted to the Observants back in December 1485, which states that the king considered the celebration of the Eucharist the greatest work of mercy and piety, for through it souls would be purged and sinners led back to grace. As Henderson points out:

Henry VII’s requests for prayers and masses were huge, constant, and costly, certainly an outlay that would not seem a likely choice for a more worldly king with secular objectives in mind, but one that comfortably fits an individual who is decidedly more devout. They assuredly suggest someone whose beliefs were closely aligned with the thinking of late medieval affective piety.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodman suggested that Henry VII’s support of the religious houses, as well as his “lavish almsgiving,” might have been carried out to secure the loyalty of those houses. Vergil, in contrast, noted simply that the king was “particularly fond of those Franciscan friars whom they call observants,” and once again the evidence seems to bear him out. In his will, Henry VII referred specifically to his “long contynued devocion towards Saint Fraunces,” and to his charity toward the Observant friars. Both statements now appear to have been revealingly accurate. He had always had “a speciall confidence,” he wrote, in their devout prayers for his well being during his lifetime and hoped that the friars would continue to remember him in prayer after his death. For that reason, he said, and out of his concern that other support might not be forthcoming to serve their basic needs, he bequeathed substantial sums to the six Observant convents in England. Besides those provisions though, he left still other funds for the completion or improvement of their individual convents and gardens. Throughout his reign, he provided them with annual and sometimes monthly funds, as well as food, drink, books, clothing, and upkeep for their buildings.

— Virginia K. Henderson, “Rethinking Henry VII: The Man and His Piety in the Context of the Observant Franciscans” In: Reputation and Representation in Fifteenth-Century Europe (2004)

#henry vii#historian: virginia k henderson#historian: anthony goodman#reputation and representation in fifteenth-century europe#dailytudors

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Related to the gifset I’ve just reblogged, I found an incredible article by Virginia K. Henderson where she is critical of the traditional ‘authorities’ on Henry VII’s piety—Chrimes, Knowles—and even of Anthony Goodman’s Henry VII and Christian Renewal:

Chrimes considered the description of Henry VII that Polydore Vergil completed shortly after the death of the king to be “the fullest and on the whole probably the most reliable” one available. Yet, even though he quoted it at length in his biography and readily acknowledged that Henry VII was reputed to have been a sound churchman, Chrimes chose not to accept Vergil’s statements concerning the king’s devotional habits. He turned instead to the midtwentieth-century work of David Knowles, as others have done, to assess the piety of the king. Whether in truth, as topos, or for eulogistic effect, Vergil reported that Henry VII was “the most ardent supporter of our faith” and someone who “daily participated with great piety in religious services,” but the stance of Knowles was quite the opposite. According to him, Henry VII “was not personally interested in religion in its theological or devotional aspects, still less in its spiritual depth . . . His actions and policies, as we see them, were earthbound.” Both Anthony Goodman and John A. F. Thomson acknowledged the importance of pious devotions and the Church to Henry VII, but they did so with an eye to their value as components in the political image of the king, rather than as an indication of his personal spiritual involvement.

In contrast, the evidence I have found suggests that Henry VII took his religious devotions seriously, as Vergil indicated, and that he was strongly influenced in his beliefs by his experiences and upbringing abroad. Moreover, probably because of the unique circumstances of his youth spent in exile and its ramifications, he appears to have conceived of himself and his reign as divinely ordained in the tradition of sacred kingship, however convenient that might appear now from a modern perspective.

I find the last sentence to be especially true. Almost every action Henry VII ever took has been regarded as politically motivated and ‘Tudor propaganda’ but people are quick to dismiss (or even consider in the first place) the prevailing attitudes and conceptions of kingship and religious devotion of his time.

#i love a good academic fight#text posts#henry vii#historian: virginia k henderson#historian: s. b. chrimes#historian: anthony goodman#historian: david knowles#historian: polydore vergil#historian: john thomson

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

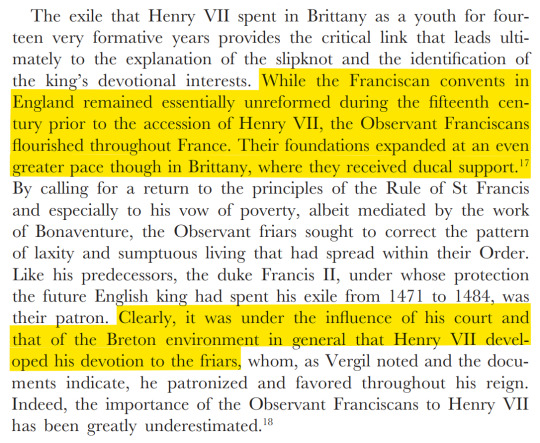

— Virginia K. Henderson, “Rethinking Henry VII: The Man and His Piety in the Context of the Observant Franciscans” In: Reputation and Representation in Fifteenth-Century Europe (2004)

#*eye emoji*#henry vii#historian: virginia k henderson#reputation and representation in fifteenth-century europe#dailytudors

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

— Virginia K. Henderson, “Rethinking Henry VII: The Man and His Piety in the Context of the Observant Franciscans” In: Reputation and Representation in Fifteenth-Century Europe (2004)

#henry vii#historian: virginia k henderson#reputation and representation in fifteenth-century europe#dailytudors

15 notes

·

View notes