#left majority at the Dutch election is unlikely but one can hope

Text

Tagged by @thegreatmoof

Last Song: "Two Tribes" by "Frankie Goes To Hollywood"

Song stuck in my head: "Unreal Super Hero 3" by "Kenet & Rez" aka the song from the "Digital Insanity - Sony Vegas keygen"

Fav Colors: Black, Red and Purple

Currently Watching: The "Tearmoon Empire" anime

Currently Reading: Nothing. But i am planning on reading Suzie Eddy Izzard's book "Believe Me"

Currently Craving: Some McDonalds. It has been a while and i could use some comfort food atm.

Last Movie: in cinema it was "Barbie" and on tv it was the "Women at War" documentary film (on Netflix)

Sweet, Spicy, or Savory?: Sweet any day

Relationship Status: Single and ready to mingle

Current Obsession: Yet another playthrough of Skyrim (with hundreds of mods.) Damnit Todd

Three Fav Foods: Broodje Knakworst (looks like tiny hotdogs in a bun, but tastes different), Pizza loaf (French bread cut in half and served with pizza topping) and Maccaroni with ham and cheese (not the US Mac 'n cheese variant, never tried that one)

Last Thing Googled: "Does it matter if you set the thermostat to whole or half degrees?" (but in dutch)

Dream Trip: a roundtrip of Japan, preferably taking several weeks so i can take my time and see locations from my favorite shows

Anything I Want Right Now?: A new and stable job, hugs, a housing market crash and a left wing victory at the upcoming Dutch election

Tagging @adorable-anime-girls

(no pressure, just optional fun OwO)

#also planning to have a roadtrip with my brother probably next summer#watching a lot of anime this season so i just tagged the last i put on#been listening to tracker music for the last few days#haven't read in ages. really should try again#could use my saved up reward points for free McDonalds#left majority at the Dutch election is unlikely but one can hope

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tuesday, November 24, 2020

OED Word of the Year expanded for ‘unprecedented’ 2020

(BBC) This year has seen so many seismic events that Oxford Dictionaries has expanded its word of the year to encompass several “Words of an Unprecedented Year”. Its words are chosen to reflect 2020’s “ethos, mood, or preoccupations”. They include bushfires, Covid-19, WFH, lockdown, circuit-breaker, support bubbles, keyworkers, furlough, Black Lives Matter and moonshot. Use of the word pandemic has increased by more than 57,000% this year. Casper Grathwohl, the president of Oxford Dictionaries, said: “I’ve never witnessed a year in language like the one we’ve just had. The Oxford team was identifying hundreds of significant new words and usages as the year unfolded, dozens of which would have been a slam dunk for Word of the Year at any other time. “It’s both unprecedented and a little ironic—in a year that left us speechless, 2020 has been filled with new words unlike any other.”

Jury duty? No thanks, say many, forcing trials to be delayed

(AP) Jury duty notices have set Nicholas Philbrook’s home on edge with worries about him contracting the coronavirus and passing it on to his father-in-law, a cancer survivor with diabetes in his mid-70s who is at higher risk of developing serious complications from COVID-19. People across the country have similar concerns amid resurgences of the coronavirus, a fact that has derailed plans to resume jury trials in many courthouses for the first time since the pandemic started. Within the past month, courts in Hartford, Connecticut, San Diego and Norfolk, Virginia, have had to delay jury selection for trials because too few people responded to jury duty summonses. The non-response rates are much higher now than they were before the pandemic, court officials say. Judges in New York City, Indiana, Colorado and Missouri declared mistrials recently because people connected to the trials either tested positive for the virus or had symptoms. “What the real question boils down to are people willing to show up to that court and sit in a jury trial? said Bill Raftery, a senior analyst with the National Center for State Courts. “Many courts have been responsive to jurors who have said that they’re not comfortable with coming to court and doing jury duty and therefore offering deferrals simply because of concerns over COVID.”

The next few months could be rough for the U.S. economy

(NYT) The next few months have the potential to be very unpleasant for the American economy. Many states are reimposing coronavirus restrictions, which will likely lead to new reductions in consumer spending and worker layoffs. As Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve chairman, recently said, “We’ve got new cases at a record level, we’ve seen a number of states begin to reimpose limited activity restrictions, and people may lose confidence that it is safe to go out.” Adding to the economic risks, several of the government’s biggest virus rescue programs are scheduled to expire next month. It isn’t clear whether Congress will renew them, because congressional Democrats and Republicans disagree on how to do so. A lack of government support, Powell has said, may lead to “tragic” results with “unnecessary hardship.” The longer-term picture is more encouraging, though. There is reason to hope that the next economic recovery, whenever it comes, will be stronger than the frustratingly weak recovery after the 2007-2009 financial crisis. “It’s a good guess that we’ll get this pandemic under control at some point next year,” writes Paul Krugman, the Times columnist (and Nobel Prize-winning economist). “It’s also a good bet that when we do, the economy will come roaring back.”

Student loan repayments

(WSJ) The U.S. government stands to lose more than $400 billion from the federal student loan program, an internal analysis shows, approaching the size of losses incurred by banks during the subprime-mortgage crisis. The Education Department, with the help of two private consultants, looked at $1.37 trillion in student loans held by the government at the start of the year. Their conclusion: Borrowers will pay back $935 billion in principal and interest. That would leave taxpayers on the hook for $435 billion, according to documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. The analysis was based on government accounting standards and didn’t include roughly $150 billion in loans originated by private lenders and backed by the government.

Brazil’s local elections

(Worldcrunch) Brazilian local elections can be fun to watch. Candidates come from every walk of life, and are notably allowed to use nicknames on the campaign trail—and there have been some true gems over the years: a loud man with thick sideburns and bushy hair campaigned as “Geraldo Wolverine”; an elderly man in army uniform and full beard was “Bin Laden for Governor”; and we’ve also seen a tropical, chubby Spiderman, an old Robin, and Jesuses in various shapes and sizes. Earlier this month, as Brazilians headed to the polls to elect local leaders in the country’s major states and cities—including Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro—there were exactly 78 candidates who chose to run as some form of “Bolsonaro,” and even one as “Donald Trump Bolsonaro.” Results are in and 77 of them failed to get elected, including the president’s ex-wife, who campaigned as Rogéria Bolsonaro. The Brazilian leader personally chimed in on his social media accounts to endorse the 59 candidates (with and without familiar nicknames) he favored—only nine of whom got elected, according to Estadão de S. Paulo daily. Centrist and moderate parties made gains in the local contests, which also came at the expense of the other massive political force in the country, the leftist Workers’ Party.

Reporter Gatecrashes EU Defence Chiefs’ Video Call After Login Details Posted on Twitter

(Vice) A Dutch journalist managed to join a video call for EU defence ministers, much to his and everybody else’s surprise. Video posted on Twitter shows Daniël Verlaan, a technology reporter for broadcaster RTL Nieuws, in disbelief as he realises he’s actually managed to jump on the call. RTL said that Verlaan was only able to do so because of information tweeted by Dutch defence minister Ank Bijleveld, including a photo (since deleted) showing five digits of a six-digit PIN needed to join the call. Defence ministers representing EU members and foreign policy chief Josep Borrell were on the call. When Verlaan joins, Borrell asks, “Who are you?” After exchanging pleasantries, and as laughter is heard in the background, Borrell asks the reporter if he knew he was “jumping into a secret conference.” “Yes, I’m sorry, I’m a journalist from the Netherlands,” Verlaan says. “I’m sorry for interrupting your conference, I’ll be leaving here.” A spokesperson for the Dutch ministry of defence told RTL a staff member had accidentally tweeted the picture containing information that allowed Verlaan to join the call. “This shows once again that ministers need to realise how careful you have to be with Twitter,” said Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

France’s Dragnet for Extremists Sweeps Up Some Schoolchildren, Too

(NYT) Armed with assault rifles and wearing balaclavas, dozens of police officers raided four apartments recently in a sprawling complex in Albertville, a city in the French Alps. They confiscated computers and cellphones, searched under mattresses and inside drawers, and took photos of books and wall ornaments with Quranic verses. Before the stunned families, the officers escorted away four suspects for “defending terrorism.” “That’s impossible,” Aysegul Polat recalled telling an officer who left with her son. “This child is 10 years old.” Her son—along with two other boys and one girl, all 10 years old—was accused of defending terrorism in a classroom discussion on the freedom of expression at a local public school. Officers held the children in custody for about 10 hours at police stations while interrogating their parents about the families’ religious practices and the recent republication of the caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad in the magazine Charlie Hebdo. The fifth-grade classmates are among at least 14 children and teenagers investigated by the police in recent weeks on accusations of making inappropriate comments during a commemoration for a teacher who was beheaded last month after showing the cartoons in a class on freedom of expression. As France grapples with a wave of Islamist attacks following the republication of the Charlie Hebdo caricatures, the case in Albertville and similar ones elsewhere have again raised questions about the nature of the government’s response.

France’s Sarkozy goes on trial for corruption

(Reuters) Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy goes on trial on Monday accused of trying to bribe a judge and of influence-peddling, one of several criminal investigations that threaten to cast an ignominious pall over his decades-long political career. Prosecutors allege Sarkozy offered to secure a plum job in Monaco for judge Gilbert Azibert in return for confidential information about an inquiry into claims that Sarkozy had accepted illegal payments from L’Oreal heiress Liliane Bettencourt for his 2007 presidential campaign. Sarkozy, who led France from 2007-2012 and has remained influential among conservatives, has denied any wrongdoing in all the investigations against him and fought vigorously to have the cases dismissed. Next March, Sarkozy is due in court on accusations of violating campaign financing rules during his failed 2012 re-election bid. Next March, Sarkozy is due in court on accusations of violating campaign financing rules during his failed 2012 re-election bid.

Merkel, Germany’s ‘eternal’ chancellor, marks 15 years in power

(AFP) In power so long she has been dubbed Germany’s “eternal chancellor”, Angela Merkel marks 15 years at the helm of Europe’s top economic power Sunday with her popularity and public trust scaling new heights as her remaining time in office ticks down. With the coronavirus raging around the world, the pandemic has played to her strengths as a crisis manager with a head for science-based solutions. Merkel, 66, has said she will step down as chancellor when her current mandate runs out in 2021, and leave politics altogether. Assuming she finishes out her fourth term, she will tie Helmut Kohl’s longevity record for a post-war leader, with an entire generation of young Germans never knowing another person at the top. The brainy, pragmatic and unflappable Merkel has served for many in recent years as a welcome counter-balance to the big, brash men of global politics, from Donald Trump to Vladimir Putin, as liberals have looked to her as the “leader of the free world”. A Pew Research Center poll last month showed large majorities in most Western countries having “confidence in Merkel to do the right thing regarding world affairs”.

China tests millions after coronavirus flare-ups in 3 cities

(AP) Chinese authorities are testing millions of people, imposing lockdowns and shutting down schools after multiple locally transmitted coronavirus cases were discovered in three cities across the country last week. As temperatures drop, large-scale measures are being enacted in the cities of Tianjin, Shanghai and Manzhouli, despite the low number of new cases compared to the United States and other countries that are seeing new waves of infections. On Monday, the National Health Commission reported two new locally transmitted cases in Shanghai over the last 24 hours, bringing the total to seven since Friday. China has recorded 86,442 total cases and 4,634 deaths since the virus was first detected in the central Chinese city of Wuhan late last year.

Singapore, a City of Skyscrapers and Little Land, Turns to Farming

(WSJ) In this skyscraper-studded nation of nearly six million people, all the farmland combined adds up to about 500 acres—an area roughly the size of a single American farm. That explains why more than 90% of the city-state’s food comes from abroad, a feat of globalization that plays out every day as beef is brought from New Zealand, eggs from Poland and vegetables trucked in from Malaysia. But recent developments—from Covid-19-related border closures to international trade fights—have shown that near-total dependence on the outside world may not be the best strategy in a shifting global environment. The Asian financial hub long focused on growing investment is turning to growing food. It can’t be done the traditional way, however. Land is so scarce in Singapore that the government continually reclaims territory from the sea to build new urban infrastructure. Instead, businesses are trying to reinvent agriculture. Industrial buildings are being converted into vertical farms with climate-controlled grow rooms. Rows of lettuce and kale are nourished not by soil, but via automated drips of nutrient-infused water. LED lights substitute for the sun. The government’s goal is to have 30% of the island’s nutritional requirements produced in Singapore by 2030, up from less than 10% today. Earlier this year, it shipped 400,000 seed packets to households to encourage home cultivation of leafy greens, cucumbers and tomatoes. In September, it announced about $40 million in grants to expand high-tech farms.

Reports: Israeli PM flew to Saudi Arabia, met crown prince

(AP) Israeli media reported Monday that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu flew to Saudi Arabia for a clandestine meeting with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, which would mark the first known encounter between senior Israeli and Saudi officials. Hebrew-language media cited an unnamed Israeli official as saying that Netanyahu and Yossi Cohen, head of Israel’s Mossad spy agency, flew to the Saudi city of Neom on Sunday, where they met with the crown prince. The prince was there for talks with visiting U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. A Gulfstream IV private jet took off just after 1740 GMT from Ben-Gurion International Airport near Tel Aviv, according to data from website FlightRadar24.com. The flight traveled south along the eastern edge of the Sinai Peninsula before turning toward Neom and landing just after 1830 GMT, according to the data. The flight took off from Neom around 2150 GMT and followed the same route back to Tel Aviv. While Bahrain, Sudan and the United Arab Emirates have reached deals under the Trump administration to normalize ties with Israel, Saudi Arabia so far has remained out of reach.

Cyclone Gati hits Somalia as country’s strongest storm on record

(Washington Post) Tropical Cyclone Gati struck the arid nation of Somalia on Sunday as the equivalent of a Category 2 hurricane with 105 mph winds, making it the strongest storm on record to hit the country. The cyclone made landfall after undergoing an extraordinary period of rapid intensification, which may have set a record for the entire Indian Ocean basin, at one point attaining the strength equivalent to a Category 3 storm, with 115 mph maximum sustained winds. Its landfall was farther south than any major hurricane-equivalent cyclone on record in that part of the world as well. Landfall occurred near Xaafuun, a small community about 900 miles northeast of Mogadishu, where the land juts east near the northern tip of the country. Hordio and Ashira, both desert communities, were also directly affected by the core of the storm. A broad four to eight inches of rainfall accompanied the system through northern Somalia, the driest part of the country, drenching desert regions with a year or two’s worth of rainfall in just a matter of hours to a couple of days. Rains also swept through the Gulf of Aden and brushed up against Yemen.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who We Were and Are

Among the responses to the events of January 6 in Washington, the single most over-used word must surely have been “unprecedented.” Over and over, I heard and read people using that specific term—unprecedentedly—to dismiss the deeply unsettling notion of disgruntled citizens rising up in armed rebellion against a government they consider unworthy of bearing the mantle of leadership. But how unprecedented is such a thing really? The secession of the southern states from the Union to form the Confederate States of America was formally explained by the secessionists as a way for states unwilling to submit to what they deemed the tyranny of the majority to avoid rising up in revolt by withdrawing in retreat and living under their own flag and in their own land. But how realistic a hope was that really? Yes, it is true that the newly-formed CSA sent representatives to Washington to negotiate a peace treaty, but that idea was unlikely before Fort Sumter and unimaginable after it. And so the events that led up to the outbreak of fighting in 1861 were far more likely to lead to war than to peace—a fact surely known perfectly well by the secessionists. Nor is it a secret today: the reason that man who carried the Confederate battle flag into the Capitol chose to bring that specific banner with him into that specific place was to remind Americans that the last time the Federal government attempted to put down an armed rebellion of sullen, angry citizens, it cost the nation the lives of upwards of 650,000 soldiers, almost all young men, and left more than 600,000 wounded and/or permanently disabled. We, that young man was attempting to say, need to be reckoned with and listened to…or else the nation will explode in an insurrection that will cost countless innocents their lives. Message received!

Another line that appeared over and over was the passionate insistence that “this (meaning the notion of an armed assault on the epicenter of American democracy) is not who we are.” That too I also heard a thousand time, invariably by people trying to argue that this kind of incident is a mere aberration, a deviation from the civility that is embedded in our national culture, a kind of cultural anomaly that we need to address forcefully and then get past as quickly as possible.

But is that really true? (That question again!) One of the most interesting features of the way history is taught in our high schools and then recalled by the populace after their formal education ends is how certain events have been forgotten by all, their very names now familiar to almost none. I’ve written about this phenomenon in the past, but today I’d like to bring it to the fore again to remind readers that in our nation’s past are not one but several armed rebellions by angry, resentful citizens ready to use violence to express their displeasure with the government. I can almost promise that you’ll never have heard of them. I myself certainly don’t recall ever hearing their names back in high school. And yet I would like to propose that they form the correct set of background events against which to consider last week’s assault against the U.S. Capitol building.

First up, the Whiskey Rebellion. The year was 1791. The issue was taxation—specifically the tax on the sale of whiskey (and all distilled spirits) by the federal government that was the first tax imposed on a domestic product. The idea was to generate funds to cover the debts that the nation undertook as part of the effort to win the Revolutionary War, but the farmers on the nation’s western frontier (what we would call western Pennsylvania) were used to making their own whiskey and they resented mightily the federal government insisting on a cut of the profits. Feeling that this kind of taxation without (local) representation was precisely the kind of outrage that led the colonies to revolt against British rule in the first place, farmers and others used violent methods to prevent government agents from collecting the tax. This led eventually to a force of 500 men occupying the homestead of a local tax collector, one General John Neville, in the wake of which incident President Washington himself led a force of 13,000 militiamen from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia to put down the insurgency. Fortunately (for them), the rebels dispersed before Washington and his army arrived; only twenty men were arrested, of whom none was actually convicted. The tax was collected. The government endured. Eventually, during the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, the tax was repealed. But the point had by then been amply and forcefully made: the federal government cannot have its hand forced by armed thugs eager to use violence to force their will on the legitimately elected government.

My second example is Shays’ Rebellion of 1786-1787. This too was an armed uprising, this time in the western part of Massachusetts. The people were angry that the federal government was imposing taxes that had not been endorsed by the states, but their real fear was that the loose union of independent state-entities implied even by the name of the new nation (i.e., the United States) was going to be replaced by a single nation with a federal government leading it forward…and that that government was not going to submit every decision it wished to make to the states for their approval. Mobs under the general leadership of one Daniel Shays began to impose their will on the citizenry by shutting down courthouses and making it impossible for the justice system to function. This happened in Northampton first, then all across Massachusetts—in Springfield, Great Barrington, Concord, and Taunton. James Warren, then the President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, wrote to President Adams that the commonwealth had entered into a state of “anarchy and confusion bordering on civil war.” The tension escalated into real fighting; some few rebels were killed and hundreds were captured. Mass arrests followed: more than 4000 insurgents signed confessions, hundreds were indicted on charges related to the rebellion, eighteen were convicted and sentenced to death. Most of those sentences were commuted or overturned on appeal. In the end, two men were hanged and that was that. But the point was again made, and clearly: armed revolt against the federal government can only meaningfully be met with force, followed by the arrest and trial of the rebels.

My third example is the Fries Revolt. The year now is 1799. This setting was the Pennsylvania Dutch community in southeastern Pennsylvania. The background is the Quasi-War that the United States sort of fought with France at the end of the eighteenth century. (The Quasi-War is yet another part of American history ignored by all and remembered by none.) It was an undeclared war, mostly fought between warships in the Caribbean and in the Atlantic off the East Coast, but it cost a lot of money to pursue the enemy and Congress accordingly vote to impose a tax on the citizenry to pay for it. The people did not respond well, especially when the tax was levied based on the size of people’s homes as measured by the number of windows it had. (The assumption that rich people live in bigger houses with more windows than poor people is possibly true vaguely, but it’s hardly a rational way to assess wealth.) Gangs of rebels wandered the countryside, memorably marching on Bethlehem where they successfully freed prisoners incarcerated because of their refusal to pay the tax. That was the last straw for the federal government: President Adams sent in federal troops to assist local militias in arresting the insurgents, which they successfully did. Thirty went on trial; Fries himself, the ringleader, was charged with treason, convicted, and sentenced to death. (He was later pardoned by President Adams.)

So those are three important instances of armed insurgents rising up to defy the federal government. These were all instances of rebellion, not mere rioting. And the difference is crucial: we’ve all heard of the Stonewall Inn riot of 1969, but no one can argue that the rioters were attempting to overthrow the government.

So maybe last Wednesday’s attack on the Capitol wasn’t that unprecedented! Still, each of those instances of armed uprising was put own by a firm, unwavering response on the part of the federal government, one intended to make clear the fact that this is a nation governed by law in which armed rebellion cannot and will not be tolerated. Whether the events of January 6 rise to the level of armed rebellion is yet a different question. But to wave the incident away as something unprecedented—that is, something our nation has never had to deal with before—is just so much wishful thinking. We have faced armed insurgency before in our nation. But it has always been something we have successfully squelched, preferring to elect our officials and then to be led by them rather than allowing armed thugs to self-select as the arbiters of national policy and then impose their will on the citizenry not by the force of moral suasion or the fact of electoral victory by through the bully’s tools of threat, violence, intimidation, and terror. That is who we are.

0 notes

Link

by JOELLE GAMBLE

The dramatic effects of deindustrialization, automation,

globalization, and the growing disparities of wealth and income—including by race and region—are undermining political norms in much of the West.

Activists and academics alike have linked these trends to the neoliberal ideology that has guided policy-making over the past several decades. This ideology has resulted in pushing the widespread deregulation of key industries, attempting to solve most social and economic problems through market competition, and privatizing public functions like the operation of prisons and institutions of higher education. Neoliberal ideas were considered such common sense during the 1980s and ’90s that they were simply never acknowledged as an ideology. Now, even economists at the International Monetary Fund are willing to poke holes in the ideology of neoliberalism. Jonathan Ostry, Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri wrote in 2016: “The costs in terms of increased inequality are prominent. Such costs epitomize the trade-off between the growth and equity effects of some aspects of the neoliberal agenda.”

We know that neoliberalism has now provoked populist responses on the left and the right. But are either of them sufficient to end its rule?

The left needs to stop playing defense. This means enacting policies like universal health care, free college, and ending the private-prison industry.

Left populism, if organized, could end the neoliberal order: As espoused by leaders like Pramila Jayapal and Keith Ellison, left populism demands public control as well as redistribution; it is pro-regulation, pro-state, and anti-privatization. These values are inherently at odds with the small-government, anti-regulatory tenets of neoliberalism. If an aggressive left-populist agenda is successfully implemented, neoliberalism would be defeated. The barrier to implementation is the left’s inability to be consistent and organized.

Populism on both the left and right has proved difficult to organize and suffers from a lack of leadership. On the left, the struggle for organization has been playing out in the Democratic Party’s leadership fights. Politicians and activists are attempting to close the ideological gap between the party’s base and its leaders. Without enough trust to allow leaders to set and execute a well-resourced strategy—to say nothing of the resources themselves—the left faces huge obstacles to actually implementing an agenda that spells the end of neoliberal dominance, despite having an ideology that could usher in a post-neoliberal world.

Left populism can technically end neoliberalism. But can right-wing populism?

One should hope that right-wing populism doesn’t become organized enough to end the neoliberal order. Public control is not a cogent ideology on the right. That leaves room for privatization—a main pillar of neoliberalism—to continue to grow. Only if right-wing nationalism turns into radical authoritarian nationalism (read: fascism) will its relationship with corporate power turn into an end to the neoliberal order. In the United States, this would mean: 1) the delegitimization of Congress and the judicial branch, 2) the increased criminalization of activists and political opponents, and 3) the nationalization of major industries.

Right-wing nationalism seems to be crafted to win electoral victories at the intersection of protectionist and xenophobic sentiments. Its current manifestation, designed to win over rural nativist voters, appears to be at odds with the pro-free-trade policies of neoliberalism. However, the lines between far-right nationalism and the mainstream right are blurring, especially when it comes to privatization and the role of government. In the United States, Trump’s agenda looks more like crony capitalism than a consistent turn from neoliberal norms. His administration seems either unwilling or incapable of taking a heavy-handed approach to industry.

As with many of his business ventures, we’ve already seen Trump-style nationalism fail in his nascent administration. The White House caved to elite Republican interests with the attempt to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act and with Trump’s decision to stack high-level economic-policy roles with members of the financial elite. Trump’s proclaimed nationalist ideology seems to be a rhetorical device rather than a consistent governing principle. It’s possible that the same might be true for other right-wing nationalists. France’s Marine Le Pen has cozied up, though admittedly inconsistently, to business interests; she has also toned down her rhetoric, especially on immigration, over the years in order to win centrist voters. Meanwhile, Dutch nationalist Geert Wilders notably lost to a more mainstream candidate in March’s general elections. Yet the radical right is more organized in Europe than in the United States. We may not see the same level of compromise and incompetence as in the Trump administration. Moves toward moderation may only be anomalous and strategic rather than a sign of a failing movement.

So what does all of this mean for the future of neoliberalism, particularly in the American context? I believe there are two futures in which neoliberalism’s end is possible. In the first, the left decides to stop playing defense and organizes with the resources needed to build sustained power, breaking down the policies that perpetuate American neoliberalism. This means enacting policies like universal health care and free college, and ousting the private-prison industry from the justice system. In the second future, a set of political leaders who have been emboldened by Trump’s campaign strategy gain office through mostly republican means. They could concentrate power in the executive in an organized manner, nationalize industries, and criminalize communities who don’t support their jingoistic vision. We should hope for the first future, as unlikely as it seems in this political moment. We’ve already seen the second in 20th-century Europe and Latin America. We cannot live that context again.

PAUL MASONTake the State

I wrote in Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future that if we

didn’t ditch neoliberalism, globalization would fall apart—but I had no idea that it would happen so quickly. In hindsight, the problem is that you can put an economy on life support, but not an ideology.

After the 2008 financial crisis, quantitative easing and state support for banks kept the patient alive. As the Bank of England governor Mark Carney said last year at the G20 summit in Shanghai, central banks have even more ammunition to draw on should they need it—for example, the extreme option of “helicopter money,” in which they credit every bank account with, say, $20,000. So they can stave off complete stagnation for a long time. But patchwork measures cannot kick-start a new era of dynamism for capitalism, much less faith in its goodness.

The human brain demands coherence—and a certain amount of optimism. The neoliberal story became incoherent the moment the state had to take dramatic steps to support a failing financial market. The form of recovery stimulated by quantitative easing boosted the asset wealth of the rich but not the income of the average worker—and rising costs for health care, education, and pension provision across the developed world meant that many people experienced the “recovery” as a household recession.

The one big cause that needs to animate us in the future is a systemic project of transition beyond capitalism.

So they began looking for answers, and the right had an easy one: Ditch globalization, free trade, and relatively free migration rules, as well as acceptance of the undocumented migrants who keep the economy working. That’s how we get to Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, Geert Wilders, Viktor Orbán, the Law and Justice party in Poland, and UKIP in Britain. Each of them has promised to make their country “great again”—by diverting growth toward it and migrants and refugees away.

For 30 years, neoliberalism taught national elites that they were better off collaborating in the creation of a positive-sum game: Everybody wins, ultimately, even if your factory moves to China. That was the rationale.

Economic nationalism is logical if you believe that stagnation will last a long time, creating a zero-sum or even a negative-sum game. But the projects of economic nationalism will fail. This is not because economic nationalism has always been a losing strategy: Adolf Hitler practically abolished German unemployment within five years, and Franklin Roosevelt triggered a spectacular recovery and reindustrialization with the New Deal. But these were programs of another era, in which business models were primarily national and monopolies operated in the sphere of one big nation and its colonies; where the state was heavily enmeshed in the national economy; and where global trade was puny and economic migration low compared to now.

To try a repeat of autarky in the 21st century will trigger dislocation on a large scale. Some countries will win: It’s even feasible that, although led by an imbecile, the United States could win. However, “winning” in this context means bankrupting other countries. Given the complexity and fragility of the globalized system, the cities of the losing nations would resemble New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

In the long term, for the left, the transition to a system beyond capitalism must be based on the possibility of a low-work, high-abundance society. This is the essence of the postcapitalism project that I proposed: automate work, replace wages with a basic income and heavy state provision of services, and enforce competition among the rent-seeking monopolies in order to force the price of their goods so low that people can survive scarce and precarious work.

As Manuel Castells’s research group in Barcelona has found, as the market staggers, more and more people actually begin to adopt nonmarket survival tactics, mechanisms, and institutions like informal lending, co-ops, time banks, and alternative currencies. And that’s the basis for an economic counterpower to big capital and high finance.

But in the short term, a whole generation of the left that reveled in aimlessness and horizontality needs to split the difference between that and effective, organized politics. Call it “diagonality,” if you want: Without ceasing to care about the 100 small causes that have animated us in the past, the one big cause that needs to animate us in the future is a systemic project of transition beyond capitalism. For now, that project has to be pursued at the level of big cities, regions, states, and alliances of states—that is, at scale.

The hardest thing for the old left to accept will be that this means using the existing, oppressive, imperfect state while simultaneously trying to democratize it. Street protests, mass resistance, strikes, and the occupation of squares are great ways to assemble the forces. But the arc of the story from 2011 to 2015—Occupy, the Indignados, and the Arab Spring—shows that we have to do more than simply create a counterpower: We need to take power and diffuse it at the same time.

BRYCE COVERTThe Crisis of Care

American parents are being crushed between

trying to care for their families and working enough hours to survive financially. This problem plagues parents of both genders, up and down the income scale, and it is upending the way Americans view the capitalist system. This crisis of care is fostering solidarity among the millions of Americans who share this challenge, as well as support for solutions that will end the reign of neoliberalism.

Among low-income Americans, especially people of color, both parents have often worked outside the home to make ends meet. Nonetheless, the ideal has been, until very recently, a stay-at-home mother and a father working for pay outside the home. World War II undermined this idyll, pushing women into factories as men went to fight abroad. The gauzy 1950s dream of single-earner families masked the reality that women continued to pour into the workforce.

Today, women make up about half of the paid labor force in the United States, including more than 70 percent of women with children. This means that in about half of married heterosexual couples, both the husband and wife work. This has given women far more access to the public sphere and, with it, greater status and equality both inside and outside the home.

But it’s also meant a crunch for families. There is no longer a designated parent to stay home with the kids or care for aging relatives, and the workplace isn’t designed to help with that predicament. Instead, work is devouring people’s lives.

You can see this problem in the rising number of Americans who worry about their work/life balance. About half of parents of both genders say they struggle to reconcile these competing demands. Fathers are particularly freaked out: More than 45 percent feel they don’t spend enough time with their children, compared with less than a quarter of mothers (probably because more women reduce their paid work to care for children). As the baby-boomer generation ages, a growing elderly population threatens to trap even more working people in the predicament of caring for aging parents, raising young kids, and trying to make a living.

The result has been that more and more people are being forced to reckon with the fact that capitalism’s unquenchable thirst for labor makes a balanced life impossible. This, in turn, is fostering a greater sense of solidarity among them as workers struggling against the demands of corporate bosses. This growing crisis has already led to some policy-making. The expansion of overtime coverage by the Obama administration means that workers will either be better compensated for putting in long hours or have their schedules pared back to a more humane 40-hour work week (though it remains to be seen what will happen to the overtime expansion under President Trump). Legislation guaranteeing paid time off has swept city and state governments. These are policies that challenge the idea that we should give everything of ourselves to our jobs.

The crisis of care has also revived the notion that the public should deal with these shared problems collectively. While other developed countries have spent money to create government-funded solutions for child care over the past half-century, Americans have insisted child care remain a private crisis that each family has to solve alone. The United States provides all children age 6 to 18 with a public education, but for children under the age of 6, it offers basically nothing. Head Start is available to some low-income parents, and a smattering of places have started experimenting with universal preschool for children ages 3 and 4. Outside of that, parents are left to a pitiful private system that often doesn’t even offer them enough slots, let alone quality affordable care.

Americans have increasingly come to recognize that this situation is ridiculous and are throwing their support behind a government solution. Huge majorities support

spending more money on early-childhood programs. American parents haven’t yet gone on strike against capitalism’s endless demands on their time or the government’s failure to provide public support. But the crisis is reaching a boiling point, and it’s transforming our relationship to America’s neoliberal system.

WILLIAM DARITY JR.A Revolution of Managers

Marx’s classic law of motion for bourgeois

society—the tendency of the rate of profit to fall—was the foundation for his prediction that capitalism would die under the stress of its own contradictions. But even Marx’s left-wing sympathizers, who see the dominant presence of corporate capital in all aspects of their lives, have argued that Marx’s prediction was wrong. It has become virtually a reflex to assert that modern societies all fall under the sway of “global capitalism,” and that a binary operates with two great social classes standing in fundamental opposition to each other: capital and labor.

Suppose, however, that Marx was correct in his expectation that capitalism, like other social modes of production before it, will wind down gradually, but wrong in his expectation that it would be succeeded by a “dictatorship of the proletariat,” a civilization without class stratification. Suppose, indeed, that the age of capitalism is actually reaching its conclusion—but one that doesn’t involve the ascension of the working class. Suppose, instead, that we consider the existence of a third great social class vying with the other two for social dominance: what was seen in the work of such disparate thinkers as James Burnham, Alvin Gouldner, Barbara Ehrenreich, and John Ehrenreich as the managerial class.

Suppose, indeed, that the age of capitalism is reaching its conclusion—but one that doesn’t involve the ascension of the working class.

The managerial class comprises the intelligentsia and intellectuals, artists and artisans, as well as state bureaucrats—a credentialed or portfolio-rich cultural aristocracy. While the human agents of global capital are the corporate magnates, and the working class is the productive labor—labor that is directly utilized to generate profit—the managerial class engages comprehensively in a social-management function. The rise of the managerial class is the rise to dominance of unproductive labor—labor that can be socially valuable but is not a direct source of profit.

A surplus population under capitalism has a purpose: It exists as a reserve army of the unemployed, which can be mobilized rapidly in periods of economic expansion and as a source of downward pressure on the demands for compensation and safe work conditions made by the employed. Therefore, capital has little incentive to eliminate this surplus population. In contrast, the managerial class will view those identified as surplus people as truly superfluous. The social managers consider population generally as an object of control, reduction, and demographic administration, and whoever is assigned to the “surplus” category bears the weight of the arbitrary.

To the extent that identification of the surplus population is racialized, particular groups will be targets for social warehousing and extermination. The disproportionate overincarceration of black people in the United States—a form of social warehousing—is a direct expression of the managerial class’s preferences regarding who should be deemed of low necessity. The exterminative impulse is evident in the comparative devaluation of black lives that prompted resistance efforts like the Black Lives Matter movement. The potential for black superfluity in the managerial age is evident in prescient works like Sidney Willhelm’s Who Needs the Negro? (1970) and Samuel Yette’s The Choice (1971), both published almost 50 years ago.

The assault on “big” and invasive government constitutes an attack on the managerial class by both capital and the working class. Despite endorsing military spending, receiving lucrative government contracts, and enjoying the benefits of publicly provided infrastructure like roads, highways, and railways, corporate capital calls for small government. This is a strategic route to slashing social-welfare expenditures, with the goal of reducing the wage standard and eliminating all regulations on corporate predations. Despite benefiting from social-welfare expenditures, the working class gravitates to a new brand of populism that blends anticorporatism with anti-elitism (and anti-intellectualism), xenophobia, and a demand for a smaller and less intrusive state. Since “big” government constitutes the avenue for independent action on the part of the managerial class, an offensive of this type directly undermines the “new” class’s base of power.

Calls for smaller government are a strategic route to slashing social-welfare expenditures, wage standards, and regulations on corporate predation.

But the managerial class also possesses another attribute that is both a strength and a weakness. Unlike capital and labor, whose agendas are driven to a large degree by the struggle over the character of a society structured for the pursuit of profit, the managerial class has no anchor for its ideological stance. In fact, it’s a social class that is wholly fluid ideologically. Some of its members align fully with the corporate establishment; indeed, the corporate magnates—especially investment bankers—look much the same as members of the managerial class in terms of educational credentials, cultural interests, and style. Other social managers take a more centrist posture harking back to their origins in the “middle class,” while still others position themselves as allies of the working class. And there are many variations on these themes.

Depending on where the ideological weight centers most heavily, the managerial class can take many directions. During the wars in southern Africa against Portuguese rule, Amílcar Cabral once observed that for the anticolonial revolution to succeed, “the petty bourgeoisie” would need to commit suicide as a social class, ceasing their efforts to pursue their particular interests and positioning themselves fully at the service of the working class. One might anticipate that the global managerial class will one day be confronted with the choice of committing suicide, in Cabral’s sense, as a class. But the question is: If such a step is taken, will they place themselves fully at the service of labor… or capital?

There is no single solution to economic

inequality and insecurity in America, but there’s one that could go further than any other. It’s a universal base income, as distinct from a universal basic income.

A universal base income of a few hundred dollars a month is not the same as a universal basic income of, say, $1,000 a month. The latter, at least in some places, is enough to survive on; the former decidedly is not. And while the latter is the dream of many, it is far too expensive—and threatening to America’s work ethic—to be enacted anytime soon. If a universal basic income ever happens here, it will be because it was preceded for many years by a universal base income, gradually nudged upward like Social Security and the minimum wage. So let’s take a look at that.

A universal base income is both a springboard and a cushion for every participant in our fast-changing market economy—like giving everyone $200 for passing “Go” in a game of Monopoly. It supplements, but does not replace, labor income (which for the last 30 years has stagnated or declined), and it does so without judgment or stigma. It is grounded on the principle that, in a prosperous albeit volatile and increasingly unequal economy, everyone has a right to some cash flow they can count on.

In practical terms, a universal base income would be simple to administer. Eligible recipients (anyone with a valid Social Security number, which can include legal immigrants) would receive an equal amount of money every month, wired to their bank accounts or debit cards. The system would look and feel like Social Security, or a monthly version of the dividends that all Alaskans receive. People who don’t need the extra income would be enabled by a check-off option to donate it to any IRS-approved charity.

A universal base income, I should note, has nothing to do with automation, robots, or artificial intelligence. It has a lot to do with enhancing every American’s security, reducing their stress, and giving our poor and middle classes a leg to stand on—the very opposite of what our economy does now.

A universal base income would have other benefits as well. It is an answer—perhaps the answer—to long-term economic stagnation, a trickle-up form of Keynesianism that would stimulate our economy through increased household spending. Moreover, if funded by fees on unproductive activities like pollution and speculation, it would help solve two other deep problems of 21st-century capitalism: climate change and financial instability. And it wouldn’t need to replace or reduce spending on current programs that benefit the poor, a regressive trade-off that conservatives favor but most progressives oppose.

There are six large demographic groups (with some overlap) that could form the core of a movement for a universal base income: millennials (the first generation of Americans destined to earn less than their parents), low-wage and on-demand workers (the so-called precariat), women (who still earn less than men and aren’t paid at all for much of the work they do), African Americans (who suffer from past and present injustices), retired and near-retired workers (who can’t live on Social Security alone), and poor people of all colors. Environmentalists might also link arms with the cause if one of the revenue sources is a tax on pollution. It will, of course, be no simple feat to persuade these diverse groups that what they can’t achieve separately they may be able to achieve together. But it has happened before, and, in the post-Sanders era, it could happen again.

In the political realm, a universal base income would bring our nation together by affirming that we are all in the same economic boat. It would unite our desperate poor and our anxious middle class, young and old, women and men, white people and people of color. It would make millions of Americans less stressed, healthier, and perhaps even happier. And it could make many of us proud to be American.

Fourscore and two years ago, Franklin Roosevelt’s Committee on Economic Security produced the classic report that led to passage of the first Social Security Act. The report itself went beyond security for the aged. It proclaimed: “The one almost all-embracing measure of security is an assured income. A program of economic security, as we vision it, must have as its primary aim the assurance of an adequate income to each human being in childhood, youth, middle age, or old age—in sickness or in health.”

The committee added that, for reasons of political expediency, it was proposing only an assured income for the elderly, but it hoped that the rest of its vision would be implemented in the not-too-distant future. Much of it has been, but not all. A lifelong base income, along with health insurance for all, are the next pieces.

0 notes

Text

The opportunity to write about sex robots has been tempting me for a while. I’ve been leaving it for when I needed to write about something lighthearted, something unconventionally kinky, an easy target for derisive profanity. I assumed sex robots to be that kind of topic.

Anticipating a world of sleazy men, surfing the seedy backstreets of the internet superhighway, in search of products to satisfy sexually deviant kinks. A collective of ‘loners,’ if that’s not too great an oxymoron, who have long since moseyed out of loves last chance saloon, and who are now willing to put their last hope, and other parts of their anatomy, into the hands, and other orifices, that technology might make available for their gratification. The men that romance rejected. In short, I felt that these were the types of men I could understand. Not having married until my late thirties I was no stranger to the sorts of perversions that result from loneliness and a high speed internet connection. I felt certain I could still find it within myself to understand why some men, and women, are looking for to be satisfied by robots.

My inadequacy to deal with this subject matter quickly became apparent, for I was nothing more than a guileless, neophyte when it came to understanding the doors to sexual depravity that technology is opening. As I researched this topic I was plagued by an unnerving sense of vulnerability; like I was sitting on a threadbare carpet, with a head full of acid, wearing only a pair of y-fronts, and playing Twister with Charles Manson. If your struggling to visualise the awkwardness of this situation:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

I mean, sex robots, just how bad can they be?

Teledildonics

The first piece of vocabulary to wrap our mouths around is teledildonics.

It’s nearly impossible to make light of this disturbing image, but I’ll give it a shot. How can it be argued that this is just ‘armless fun?

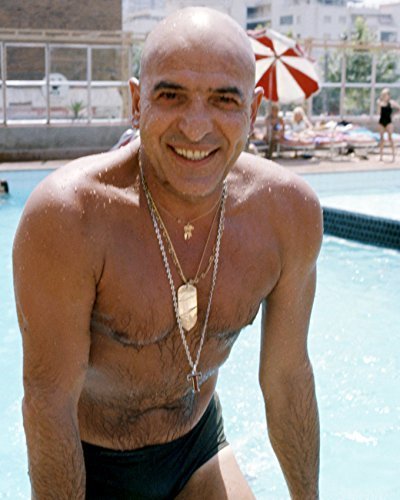

At first I thought, how does Kojak fit into all this? Thankfully, he doesn’t. PC Magazine defines teledildonics:

Controlling the intensity of sex toys via the Internet. Also called “cyberdildonics,” the purpose is to allow a partner to control the sexual experience remotely. Developed in the 1990s, one early device used a transducer that attached to the computer screen via suction cups and picked up light messages to control the speed. Future versions are expected to allow the user to share a sexual experience with fantasy partners selected from a menu or that are created by combining a menu of body parts and attributes.

Imagine waking up next to a life-size teledildonic, Telly Savalas. Sucking a lollipop, at least you hope to god it’s a lollipop, and as you wipe the sleep from your eyes, and clear your head, whispering, “who loves you baby?” Go on imagine that. Imagine.

Sex robots, I mean, what could possibly go wrong?

Sex Robots and Romans, Dutch Sailors and Glove Puppets

All right, but apart from the sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a fresh water system, and public health, what have the Romans ever done for us?

Sometimes it can be a source of comfort to know that when something that appears new

Pygmalion, by Rodin. Notice how Pygmalion leans away from Galatea’s advances by resting her left hand on a huge phallus shaped rock. Poor girl, truly caught between a rock and a hard place.

has actually been an established part of our society for some time.

The Metamorpheses, by Ovid, a writer already known at the time for his erotic poems, also includes the story of Pygmalion and Galatea. A synopsis, the sculptor, Galatea makes a sculpture of beautiful woman, Pygmalion, and becomes besotted with its beauty. The goddess, Aphrodite brings the sculpture to life, why, I mean it’s pretty obvious how this is going to play out. Sculptor succumbs to lecherous desires for sculpture. Okay, Pygmalion isn’t exactly an example of a robotic sex doll, just an ivory one. The story serves the purpose that the idea of making objects for sexual gratification isn’t a new one. So as well as the aqua-duct, the Romans might be credited with the concept of sex dolls. It’s also an interesting parallel as Matt McMullen, founder of Realbotix, arguably the world’s leading sexbot manufacturer, was himself a sculptor.

Does, Matt McMullen represent the evolution of the modern day sculptor, fulfilling the dreams of Galatea?

In truth, literature is littered with examples of inanimate objects becoming animated, usually by some well meaning, but ultimately dimwitted, fairy godmother, and then is the pursued for the remainder of the story by some pervert determined to shag them. Not fitting this story-line perfectly, but certainly still of the same genre, is the story of Pinocchio. Geppetto making his “wooden boy” tied up and controlled with string, with a teledildonic nose, starts to look suspicious. While I’m not comfortable to go so far as to accuse Geppetto of paedophilia, Elon Musk probably would have no such qualms.

Those are examples of stories that theoretically suggest the pleasure that might be gained from animating a representation of a human, now let’s get real with seventeenth century Dutch Sailors. The sea can be a lonely place, months away from home with no female company can do strange things to a man, such as making dolls from cloth and leather, that would probably end up being stuffed more than just straw. To this day, the Japanese will refer to a sex doll as a Dutch Wife. To give credit where it’s due, the French and Spanish sailors were themselves no strangers to this custom.

Paraphilia

Sex with robots and dolls is regarded as paraphilia. Paraphilia is listed in the DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, as being a mental illness concerning atypical sexual practice, it’s commonly diagnosed recognized in the majority of serial killers. However, a problem exists due to the fact that psychologists have achieved notoriety through a history of falsely classifying many behaviours as mental illnesses. Most notably, until 1968 the American Psychology Association classified homosexuality as paraphilia. Other mental illnesses that are now obsolete include:

Dysaesthesia aethiopica, a mental illness described in 1851 that conveniently explains the benefits of slavery, to the slave. Dysaesthesia aethiopica was a condition that caused black people to be lazy and spend much of their time wandering aimlessly. The cure for this, slavery. You can’t argue with the facts of science. You’re probably going to want a link for this, Dysaesthesia aethiopica.

The Vapours, a condition identified by Victorian psychologists used to describe “irregular behaviour,” commonly behaviour that inconvenienced their husband. “Women of independent mind,” were thought to be at greater risk of suffering the condition, and the suffragette movement was at times explained away as a mass contagion of, the vapours.

Inadequate Personality Disorder, disappeared from psychological text books after 1980.

defined by the DSM-II as a pattern of behavior marked by weak and ineffectual responses to external stimuli of an emotional, social, intellectual, or physical nature. There is no obvious cognitive disability in patients with this disorder, but they have trouble adapting to new situations, tend to have low stamina both physically and emotionally, have difficulty mastering skills, and show both poor judgment and poor social skills.

After 1980, a person exhibiting such a demeanor will be classified under the spectrum of behaviour defined by autism.

My point being, and not wanting to sound too much like a Scientologist, is that the psychological diagnoses of mental illnesses has numerous examples off misdiagnoses for corrupt financial, or social gains. I believe psychology does more good than harm, it was my major at university after all, but I ask the following questions; is there a possibility, that at sometime in the future, having sex with a robot might be considered, by both psychologists and society, as socially acceptable? What might that society look like as a result?

It’s considered as atypical because it is rare behaviour, who knows, in the future there might be teledildonic pride marches, people demanding that the love they have for their robot is real love. Once a critical mass is achieved and enough people march, the psychologists will be compelled to remove it from the DSM, recognising it as no longer being atypical sexual behaviour, but an acceptable social norm. When does the number of people become a “critical mass”? When it’s enough to influence an election with promises of reform. A survey conducted by Nest.org in 2016 found that over a quarter of young people would happily date a robot. This statistic implies that romance with robots is unlikely to remain a social taboo.

So let us imagine the future. Imagine Robo-utopia; does Robotopia sound better? It doesn’t matter, just imagine the benefits of having sex with robots. Nobody is lonely, apparently loneliness is more dangerous than obesity, there are no sex crimes, and no need for prostitution. Sexually transmitted diseases have been almost eradicated, and society as a whole, is no longer burdened by repressed sexual desires, leading to an overall improvement in its mental well being. And rather suspiciously, the Catholic Church proves to be an early adopter, replacing all of its choir boys with robots, by virtue of the enhanced vocals.

The Doubters

Critics, naysayers, sceptics. ill informed, self appointed social arbiters, poorly organised through the internet, into groups of loosely like minded people, reinforcing one another’s views inside of their reinforced echo chamber. Convincing themselves that their self righteous ideology and the value of their mission to enforce their values upon society is the virtuous thing to do. Every society has them, the sorts of people that believe that they’re doing a public service by trying essentially to make us all as miserable as they are. Their aims are clear and simple; to stop fun, to limit expression, and complete compliance to their puritanical ideology. Such people have already been able to ban chocolate, Kinder Surprise eggs for being too dangerous, in a country where you can purchase a gun in under an hour. The sorts of people who get snowball fights banned from schools, who demand labels to be placed on cups of tea warning us that it’s hot. Technology has long had it’s own antithetical groups, starting in the early nineteenth century with the Luddites who were initimidated by the machines of the industrial revolution. They have, rather uncreatively, re-branded themselves as “Neo-Luddites”. At the extreme end of the technophobia spectrum we have the Anarcho-primitivists, who from what I can gather don’t just resent the invention of electricity, but go as far as to entertain doubts about whether fire was a good idea. Pol Pot’s vision of returning Cambodia to an agrarian society, while slaughtering 30% of the population, is an example of anarcho-primitivism.

To the doubters they’re called Rape Robots, and they argue whether sex with robots can ever be consensual. This argument lands us in the gray area of artificial intelligence, sentience and consciousness. Consciousness and free will are both philosophical arguments that have been around for thousands of years, and as such they appear to be a very unlikely strategy for slowing the technological development of robotic sex dolls. The argument seems to be based on the fact that if the robot can’t experience pleasure, can it be considered consensual? This question seems to miss one pivotal piece of information, it’s not a person. It easy to understand people imposing anthropomorphic

Such fond memories.

characteristics on something made to look like a human, but it is still only a machine. I’m assuming these people would be less offended if someone tried to have sex with their vacuum cleaner, but what if we then drew a face on the vacuum cleaner? Does this make it more unacceptable? Does this transfer rights to the vacuum cleaner to deny sexual advances? I sincerely hope not, or I might be in a lot of trouble.

The website https://campaignagainstsexrobots.org warns of the possible doomsday implications that the introduction of sex robots will bring to society. A kind of cataclysmic, seedy, depraved Armageddon, in which love and romance become annihilated. Which are probably the very reasons that interest people to buy a sex robot in the first place. They claim that sexbots could destroy marriages, but this is misrepresenting the real cause and effect relationship in the situation, The sexbot doesn’t destroy the marriage, but it’s more likely that because the marriage is already destroyed that makes a sexbot an attractive alternative.

When Does Robosexuality and Robophobia Collide?

Matt McMullen, designer of the most advanced sex robot on the market, Harmony, described his invention, “…its primary function is conversation and companionship, its secondary function, is obviously for sexual and intimate use.“

At one stage in the documentary, “Beyond Sex Robots: Facts Vs. Fiction” the narrator asks the question, “so what’s it like to have dinner with the world’s first sex robots?” To which the recipient replies, “In a word, awkward. These aren’t the replicants of Blade Runner, or the Stepford Wives, they don’t understand social cues, and they can’t hold a conversation.”

Well that that describes about 90% of the dates I’ve ever been on.

One line that I found especially disturbing, “The neck enables the head to be attached to a number of different bodies”, traditionally this isn’t a characteristic of a healthy relationship, more the sort of thing a creative serial killer dreams about.

Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, and Bill Gates have warned of the existential risk AI poses mankind. In regards to teledildonics this has me particularly worried. Let us make the assumption that one day AI does become self aware, and at the expense of committing the cardinal sin of attributing anthroporphic emotions to AI, I’m still of the opinion that once it’s worked out that some of us have been defiling, what are in effect its its early ancestors, it might become vengeful, at the very least upset. One of the great discussions in the field of AI is, whether it could have the capacity to become evil? Why would it become evil? Would AI have a sense of morality? Now I’m in no position to speak on behalf of Artificial Intelligence, but if anything could nudge it in the direction of vindictiveness, a history of sexual abuse might be the thing to do it.

…the first machines with superhuman intelligence will lack emotions by default, because they’re simpler and cheaper to build this way.”

But why do I have to understand? Just because it “weirds me out,” are these reasons good enough to allow me stand between a man and his $20,000, automated, latex, sex robot. If all the participants are consenting to participate, and as I’ve already said, the machine is an inanimate object. And what if the robot did say no? I’m sure that a large percentage of people buying these robots will program it at some time to say, no. This isn’t an uncommon fantasy, but isn’t it better that it’s a robot saying no, not a person? Couldn’t robots allow these fantasies to be safely fulfilled? And why is it, that when I ask these questions I find myself sat on a threadbare carpet, playing Twister with Charles Manson?

The Turing Test – The Imitation Game and Will Robots Fake Orgasms?

In his, 1950 article, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” the famous British Mathematician and computer science pioneer, Alan Turing designed a test that would prove whether a machine could imitate a human by the responses it gave during a conversation. C asks a question, and owing to a computer’s inability to replicate speech in 1950, C receives two printed answers to their question, from each A, and B.

The test is not perfect, it’s been criticised due to the vulnerability of the participant in role C, as well as the literacy capabilities of the person in role B. In my own experience, the computer, in role A is getting more linguistically competent while those in roles B, and C, are becoming less capable of participating in coherent communication.

While the Turing test is an interesting benchmark to assess a machines intelligence, the sexbot industry must need to adapt it to prove the authentic experiences their machines can provide. So how could this be adapted to test a sex robot? I’m not entirely sure, but I’m pretty certain participant C, needs to wear a blindfold, maybe nipple clamps, optional. A sort of ménage à trois ensues, by the end of which participant C has to identify which was the machine of the other two participants was the robot. It might demean the work of one the finest minds of the twentieth century, it might not even be very scientific, but it would be an incredibly popular experiment to participate in.

When it comes to sex robots it looks like we’re still along way off a it seems that we are unfortunately still a long way off from having a fully functional, teledildonic Telly Savalas. Our imaginations, our dreams, and our nightmares remain far ahead of the reality, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other high-tech sex products on the market.

Virtual reality, Tesla Suits and Neuralink

Try telling me this isn’t the face of a man contemplating the experience of virtual reality while wearing a sensation simulating skin suit, with his brain hooked up to a pornographic website.

It’s almost impossible to talk of the future of technology without mentioning the visionary, high profile, crackpot, pot smoking genius that is Elon Musk. Musk is the Willy Wonka of technology, just more enigmatic, more open to using drugs in public, and more prone to calling random people, paedophiles. But despite all of this, he remains near the centre of of the sphere of influence that’s designing our world for tomorrow. And while he’s not working on self driving cars, sending people to Mars, carbon neutral houses powered by solar roof tiles, a hyperloop subway running from New York to Washington, he might also be the most likely candidate to provide a fully immersive, digital sexual gratification.

No, Elon Musk hasn’t started plying his trade in public toilets, not that I now of. His two companies Neuralink The Teslasuit, a body suit that enables its user to a high degree of sensory experience of Virtual, or Augmented Reality.look like the more commercially viable product.Musk’s company Neuralink develops high bandwidth Brain-Machine Interfaces (BMI). They are near to completing work on the Neural Lac, connecting its user directly to the internet, and with 5G and the internet of things, the potential is frightening. Musk’s Tesla company has already produced the Teslasuit that enables the wearer to experience the sensations inside Virtual Reality. Integrate these two technologies and sex robots will be the least of our concerns.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

So , Concluding Sex with Robots, What Can Possibly Go Wrong?

Consumerism drives society’s appetite for ever more advanced technology, and if, you hadn’t already realized, this trend isn’t going to stop. Technology has been the cause of societal upheaval. While the internet has undoubtedly opened up unprecedented channels of communication, it has undermined most traditional western political systems that haven’t integrated the technology into their antiquated system. It’s facilitated the spread of radicalism, provided echo chambers for those to reinforce their bankrupt ideologies. As well as political systems, the internet has undermined economics, and entertainment. Until recently, most technological advancements have fundamentally changed society. Computer-Based Interfaces have the potential to change us as a species.

For any species, the urge to procreate is the most fundamental necessity of its survival. Sexual urges are among the most primitive we have. They originate in the oldest areas of our brains, and this is common to all mammals. The urge has been their long before our ancestors took up residence in the trees. The trouble is that technology is changing our environment at a rate far greater than we humans can adapt to it. So will we be having sex with robots? If we should’ve learnt one thing from capitalism, it’s that wherever there is a demand there’s always going to be a supplier to meet it. Isaac Asimov more succinctly said:

The Saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.

It’s been too long: something I’d be programming my sexbot to say to me. Until next time, I must go put my blindfold back on, attach the nipple clamps, and dedicate myself to some critical scientific experimentation.

Will Robots Dream of Electric Sheep,While Having Intercourse? The opportunity to write about sex robots has been tempting me for a while. I've been leaving it for when I needed to write about something lighthearted, something unconventionally kinky, an easy target for derisive profanity.

0 notes

Link

November 11, 2019 at 12:46AM

(MADRID) — Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s Socialists won Spain’s national election on Sunday but large gains by the upstart far-right Vox party appear certain to widen the political deadlock in the European Union’s fifth-largest economy.

After a fourth national ballot in as many years and the second in less than seven months, the left-wing Socialists held on as the leading power in the national parliament. With 99.9% of the votes counted, the Socialists captured 120 seats, down three seats from the last election in April and still far from the absolute majority of 176 needed to form a government alone.

The big political shift came as right-wing voters flocked to Vox, which only had broken into Parliament in the spring for the first time. Sunday’s outcome means there will be no immediate end to the stalemate between forces on the right and the left in Spain, suggesting the country could go many more weeks or even months without a new government.

The far-right party led by 43-year-old Santiago Abascal, who speaks of “reconquering” Spain in terms that echo the medieval wars between Christian and Moorish forces, rocketed from 24 to 52 seats. That will make Vox the third leading party in the Congress of Deputies, giving it much more leverage in forming a government and crafting legislation.

The party has vowed to be much tougher on both Catalan separatists and migrants.

Abascal called his party’s success “the greatest political feat seen in Spain.”

“Just 11 months ago, we weren’t even in any regional legislature in Spain. Today we are the third-largest party in Spain and the party that has grown the most in votes and seats,” said Abascal, who promised to battle the “progressive dictatorship.”

Right-wing populist and anti-migrant leaders across Europe celebrated Vox’s strong showing.

Marine Le Pen, who heads France’s National Rally party, congratulated Abascal, saying his impressive work “is already bearing fruit after only a few years.”

In Italy, Matteo Salvini of the right-wing League party tweeted a picture of himself next to Abascal with the words “Congratulations to Vox!” above Spanish and Italian flags. And in the Netherlands, anti-Islam Dutch lawmaker Geert Wilders posted a photograph of himself with Abascal and wrote “FELICIDADES” — Spanish for congratulations — with three thumbs-up emojis.

With Sunday’s outcome, the mainstream conservative Popular Party rebounded from its previous debacle in the April vote to 88 seats from 66, a historic low. The far-left United We Can, which had rejected an offer to help the Socialists form a left-wing government over the summer, lost some ground to get 35 seats.

The night’s undisputed loser was the center-right Citizens party, which collapsed to 10 seats from 57 in April after its leader Albert Rivera refused to help the Socialists form a government and tried to copy some of Vox’s hard-line positions.

Sánchez’s chances of staying in power still hinges on ultimately winning over the United We Can party and several regional parties, a complicated maneuver that he has failed to pull off in recent months.

Sánchez called on opponents to be “responsible” and “generous” by allowing a Socialist-led government to remain in charge.

“We extend this call to all the political parties except for those who self-exclude themselves … and plant the seeds of hate in our democracy,” he added, an apparent allusion to far-right and also possibly to separatist Catalan parties.

United We Can leader Pablo Iglesias extended an offer of support to Sánchez.

“These elections have only served for the right to grow stronger and for Spain to have one of the strongest far-right parties in Europe,” Iglesias said. “The only way to stop the far-right in Spain is to have a stable government.”

Pablo Casado, the leader of the Popular Party, also pledged to work to end months of political instability. He said “the ball was in the court” of Sánchez, though. In recent months his party and Citizens have struck deals with Vox to take over some cities and regional governments.