#norman belasco

Text

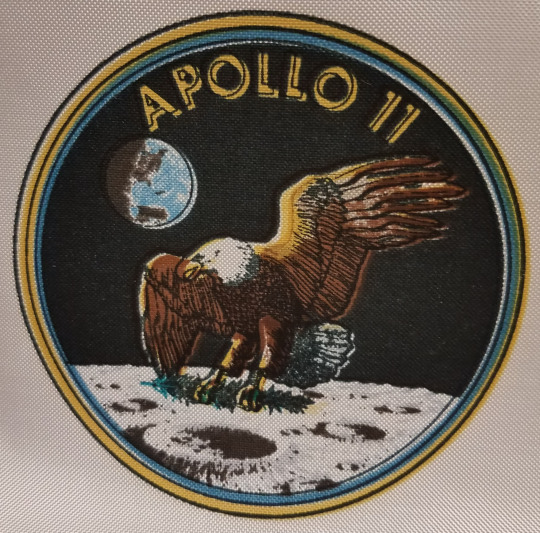

NASA Emblems and Snoopy Stickers

One of our new Houston Jewish History Archive collections contains items related to the life and work of Norman Belasco. He was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on August 26, 1923. A veteran of World War II, he served his country in the Pacific theater for four years. Upon conclusion of his military service, he obtained his Bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering from Drexel University. Belasco joined NASA in 1961. During his 20 year career, he helped to develop a flush toilet for zero gravity environments, shares a patent for inventing a medical subject monitoring system, and was Deputy Chief of Medical Operations. He passed in 2004.

Because of his work, he saved NASA-related items. At first, I thought these emblems were just unfinished patches, but they are potentially so much more. The emblems have actually been silkscreened onto glass fiber cloth, the same as the astronauts' suits. Some of the silkscreened Apollo 11 emblems were brought on that historic voyage. It's unclear if this one was, but it's neat to imagine that they've been to the moon and back.

Belasco saved another neat treasure from his time at NASA, Snoopy-themed stickers.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Violet Ethelred Krauth (October 17, 1913 – November 9, 2006), better known by the stage name Marian Marsh, was a Trinidad-born American film actress and later an environmentalist.

Violet Ethelred Krauth was born on October 17, 1913, in Trinidad, British West Indies (now Trinidad and Tobago), the youngest of four children of a German chocolate manufacturer and, as noted by encyclopaedist Leslie Halliwell in his book The Filmgoer's Companion, his French-English wife.

Owing to World War I, Marsh's father moved his family to Boston, Massachusetts. By the time she was 10, the family had relocated to Hollywood, California. Her older sister, an actress who went by the name of Jean Fenwick, landed a job as a contract player with FBO Studios. Another sister, Harriet, was a chorus girl who danced in Earl Carroll's Vanities. She changed her name to Jeanne Morgan.

Marsh attended Le Conte Junior High School and Hollywood High School. In 1928 she was approached by silent screen actress Nance O'Neil, who offered her speech and movement lessons, and with her sister Jean's help, she soon entered the movies. She secured a contract with Pathé, where she was featured in many short subjects under the name Marilyn Morgan.

She was seen in small roles in Howard Hughes's classic Hell's Angels (1930) and Eddie Cantor's lavish Technicolor musical Whoopee! (1930). The part in Whoopee! resulted from Marsh's visit to a film studio with her sister. Not long afterwards, she was signed by Warner Bros. and her name was changed to Marian Marsh.

In 1930, at age 17, Marsh had the female lead in Young Sinners, a play at the Belasco Theater. A contemporary news article reported that she "has scored a distinct hit" in her first stage production.

In 1931, after appearing in a number of short films, Marsh landed one of her most important roles in Svengali opposite John Barrymore. Marsh was chosen by Barrymore for the role of Trilby.[2] Barrymore, who had selected her partly because she resembled his wife, coached her performance throughout the picture's filming. Svengali was based on the 1894 novel Trilby written by George du Maurier. A popular play, based on the book, also titled Trilby, followed in 1895.

In the film version, Marsh plays the artist's model Trilby, who is transformed into a great opera star by the sinister hypnotist Svengali. The word "Svengali'" has entered the English language, defining a person who, with sometimes evil intent, tries to persuade another to do what he desires.

Marsh was awarded the title of WAMPAS Baby Stars in August 1931 even before her second movie with Warner Brothers was released. With her ability to project warmth, sincerity and inner strength on the screen along with critical praise and the audience's approval of Svengali, she continued to star in a string of successful films for Warner Bros., including Five Star Final (1931) with Edward G. Robinson, The Mad Genius (1931) with Barrymore, The Road to Singapore (1931) with William Powell, Under 18 (1932) with Warren William, Alias the Doctor (1932) with Richard Barthelmess, and Beauty and the Boss (1932) with Warren William.

In 1932, in the midst of a grueling work schedule, Marsh left Warner Bros. and moved to RKO, where she made Strange Justice (1932) with Norman Foster and The Sport Parade (1932) with Joel McCrea. After that, she took several film offers in Europe that lasted until 1934. She enjoyed working in England and Germany, as well as vacationing in Paris. While in England, she appeared in the musical comedy film Over the Garden Wall (1934). Back in the United States, she appeared as the heroine Elnora in a popular adaptation of the perennial favorite A Girl of the Limberlost (1934).

In 1935, Marsh signed a two-year pact with Columbia Pictures. During this time, she starred in such films as The Black Room (1935) regarded as one of Boris Karloff's best horror films of the decade, Josef von Sternberg's classic Crime and Punishment (1935) with Peter Lorre, wherein she played the sympathetic prostitute Sonya, Lady of Secrets (1936) with Ruth Chatterton, Counterfeit (1936) with Chester Morris, The Man Who Lived Twice (1936) with Ralph Bellamy, and Come Closer, Folks (1936) with James Dunn.

When her contract expired in 1937, Marsh once again freelanced, appearing steadily in movies for RKO Radio Pictures, where she made Saturday's Heroes (1937) with Van Heflin, and for Paramount Pictures, where she played a young woman caught up in a mystery in The Great Gambini (1937). She appeared with comic Joe E. Brown in When's Your Birthday? (1937), and Richard Arlen in Missing Daughters (1939). In the 1940s, Marsh played Wallace Ford's secretary in Murder by Invitation (1941) and the self-willed wife in Gentleman from Dixie (1941). In her last screen appearance, Marsh portrayed the daughter of an inventor in the comedy/mystery House of Errors (1942), which starred Harry Langdon.

In the late 1950s, she appeared with John Forsythe in an episode of his TV series Bachelor Father and in an episode of the TV series Schlitz Playhouse of Stars before retiring in 1959.

Marsh married a stockbroker named Albert Scott on March 29, 1938, and had two children with him, Catherine Mary Scott (1942-2018) and Albert Parker Scott Jr. (1944-2014). They divorced in 1959. In 1960, Marsh married Cliff Henderson, an aviation pioneer and entrepreneur whom she had met in the early 1930s. They moved to Palm Desert, California, a town Henderson founded in the 1940s.

In the 1960s, Marsh founded Desert Beautiful, a non-profit all-volunteer conservation organization to promote environmental and beautification programs.

Cliff Henderson died in 1984 and Marsh remained in Palm Desert until her death.

In 2006, at age 93, Marsh died of respiratory arrest while sleeping at her home in Palm Desert. She is buried at Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City, California.

October 17, 2015, was designated as Marian Marsh-Henderson Day by the city of Palm Desert, California.

#marian marsh#classic hollywood#classic movie stars#golden age of hollywood#pre code#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dorothy Elizabeth Gish (March 11, 1898 – June 4, 1968) was an American actress of the screen and stage, as well as a director and writer. Dorothy and her older sister Lillian Gish were major movie stars of the silent era. Dorothy also had great success on the stage, and was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame. Dorothy Gish was noted as a fine comedian, and many of her films were comedies.

Dorothy Gish was born in Dayton, Ohio. She had an older sister, Lillian. The Gish sisters' mother, Mary Robinson McConnell Gish, supported the family after her husband James Leigh Gish, a traveling salesman, abandoned the family in New York. Mary Gish, who was "a former actor and department store clerk", moved with her daughters to Indiana, where she opened a candy and catering business. In 1902, at the age of four, Dorothy made her stage debut portraying the character "Little Willie" in East Lynne, an adaptation of the 1861 English novel by Ellen Wood.

In 1910, she heard from her husband's brother, Grant Gish, who lived in Shawnee, Oklahoma and informed her that James was ill. He was in a hospital in nearby Norman, Oklahoma, so Mary sent 17-year-old Lillian to visit him. At first, Lillian wrote back to her 12-year-old sister Dorothy that she planned to stay in Oklahoma and continue her education, but after seeing her father she admitted she missed her mother and sister. So, after a few months away from them, in the spring of 1912, she traveled back. Soon afterward, their childhood friend, actress Mary Pickford, introduced the sisters to director D. W. Griffith, and they began performing as extras at the Biograph Studios in New York at salaries of 50 dollars a week. During his initial work with the sisters, Griffith found it difficult to distinguish one from the other, so he had Lillian wear a blue ribbon in her hair and Dorothy a red one. The girls, especially Lillian, impressed the director, so he included them in the entourage of cast and crew he took to California to produce films there.

Dorothy and her sister both debuted in Griffith's 1912 production An Unseen Enemy. She would ultimately perform in over 100 short films and features, many times with Lillian. Throughout her own career, however, Dorothy had to contend with ongoing comparisons to her elder or "big" sister by film critics, fellow actors, studio executives, and by other insiders in the motion picture industry. Such comparisons began even from the outset of the sisters' work for Biograph. Linda Arvidson, Griffith's first wife, recalls their initial work for the studio in her autobiography When The Movies Were Young:

Lillian and Dorothy just melted right into the studio atmosphere without causing a ripple. For quite a long time they merely did extra work in and out of pictures. Especially Dorothy, as Mr. Griffith paid her no attention whatsoever and she kept on crying and trailed along. She also continued to play in many one and two reel Biograph films, learning the difficult technique of silent film acting, and preparing for opportunity when it came. Dorothy was still a person of insignificance, but she was a good sport about it; a likable kid, a bit too perky to interest the big director, so her talents blushed unnoticed by Mr. Griffith. In 'The Unseen Enemy' the sisters made their first joint appearance. Lillian regarded Dorothy with all the superior airs and graces of her rank. At a rehearsal of 'The Wife', of Belasco and DeMille fame, in which picture I played the lead, and Dorothy the ingénue, Lillian was one day an interested spectator. She was watching intently, for Dorothy had had so few opportunities, and now was doing so well, Lillian was unable to contain her surprise, and as she left the scene she said: 'Why, Dorothy is good; she's almost as good as I am.' Many more than myself thought Dorothy was better.

Dorothy Gish's budding film career almost ended on a street in Los Angeles on Thanksgiving Day in 1914. On Friday, November 26, the 16-year-old actress was struck and nearly killed by a "racing automobile". Newspapers and film-industry publications at the time reported the event and described the severe injuries Gish sustained. The near-fatal accident occurred as Dorothy was walking with Lillian at the intersection of Vermont and Prospect avenues. According to news reports, after the car struck her, it dragged her along the street for 40 to 50 feet. Other movie personnel who were standing together on a nearby sidewalk, including D. W. Griffith, witnessed Dorothy being hit. The following day, the Los Angeles Times informed its readers about the accident:

...Miss Dorothy Gish, a moving picture actress, was seriously injured yesterday afternoon. Picked up unconscious, she was taken to the office of Dr. Tryon at number 4767 Hollywood boulevard, where it was found her injuries consisted of a crushed right foot, a deep cut in the right side, and bruises on all parts of her body. She was later removed to the home of her mother at LaBelle apartments, Fourth and Hope streets. The automobile that ran her down is owned by T. B. Loreno of No. 6636 Selma avenue, also of the moving picture game.

Subsequent news reports also describe the reaction of other pedestrians at the scene. The Chicago Sunday Tribune and trade papers reported that Dorothy's "horrified friends" rushed to her aid, with Griffith being among those who lifted the unconscious teenager into an ambulance and reportedly rode with her in the emergency vehicle. In addition to Gish's initial examination by the doctor identified by the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago newspaper and Motion Picture News stated that she was rushed to the hospital, where surgeons mended her "very badly torn" left side with "many stitches" and treated the area where one of her toes had been "cut off", presumably a toe from her badly damaged right foot. At the time of the accident, Gish was completing a two-reel romantic comedy with actor W. E. Lawrence. The film, How Hazel Got Even, had already been delayed once at Reliance-Majestic Studios due to director Donald Crisp's bout with pneumonia. Completion of the short was postponed yet again, for over a month, while Gish recuperated. Originally scheduled for release on December 27, 1914, How Hazel Got Even was not distributed to theaters until mid-February 1915.

After recovering from the 1914 accident, Gish resumed her screen career the following year, performing in a series of two- and three-reel shorts as well as in longer, more complex films such as the five-reel productions Old Heidelberg, directed by John Emerson, and Jordan Is a Hard Road, once again under D. W. Griffith's direction. Increasingly, Dorothy's appeal to both producers and audiences continued to grow in 1915, leading W. E. Keefe in the June issue of Motion Picture Magazine to recognize her as "one of the most popular film stars on the Motion Picture screen". In an article about Gish in the cited issue, Keefe also recognizes that Dorothy, career-wise, was finally emerging from her sister's shadow:

A year ago she was known as Lillian's little sister. A year's growth has changed this. Today she is taller and weighs more than her "big" sister, and is known as Dorothy Gish without always being identified as "Lillian's sister."

In 1916 and 1917, Dorothy continued to expand her acting credentials by starring in a variety of five-reelers for Fine Arts Film Company or "Griffith's studio", which was a subsidiary of Triangle Film Corporation. Her work in those years required filming on locations in New York and on the West Coast.

In the 1918 release Hearts of the World, a film about World War I and the devastation of France, Dorothy found her first cinematic foothold in comedy, striking a personal hit in a role that captured the essence of her sense of humor. As the "little disturber", a street singer, her performance was the highlight of the film, and her characterization on screen catapulted her into a career as a star of comedy films.

Griffith did not use Dorothy in any of his earliest epics, but while he spent months working on The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance, Dorothy was featured in many feature-length films made under the banner of Triangle and Mutual releases. They were directed by young Griffith protégés such as Donald Crisp, James Kirkwood, and Christy Cabanne. Elmer Clifton directed a series of seven Paramount-Artcraft comedies with Dorothy that were so successful and popular that the tremendous revenue they raked in helped to pay the cost of Griffith’s expensive epics. These films were wildly popular with the public and the critics. She specialised in pantomime and light comedy, while her sister appeared in tragic roles. Dorothy became famous in this long series of Griffith-supervised films for the Triangle-Fine Arts and Paramount companies from 1918 through 1920, comedies that put her in the front ranks of film comedians. Almost all of these films are now considered to be lost films.

"And So I Am a Comedienne", an article published in Ladies Home Journal in July 1925, gave Dorothy a chance to recall her public persona: “And so I am a comedienne, though I, too, once wanted to do heroic and tragic things. Today my objection to playing comedy is that it is so often misunderstood by the audiences, both in the theater and in the picture houses. It is so often thought to be a lesser art and something which comes to one naturally, a haphazard talent like the amateur clowning of some cut-up who is so often thought to be ‘the life of the party’. In the eyes of so many persons comedy is not only the absence of studied effect and acting, but it is not considered an art.”

She made a film in England Nell Gwynn which led to three more films. Gish earned £41,000 for these movies.

When the film industry converted to talking pictures, Dorothy made one in 1930, the British crime drama Wolves. Earlier, in 1928 and 1929, her performances in the Broadway play Young Love and her work with director George Cukor renewed her interest in stagecraft and in the immediacy of performing live again. The light comedy had proven to be popular with critics and audiences in New York, in performances on the road in the United States, as well overseas in a London production. Those successes convinced her to take a respite from film-making.

In 1939, both Dorothy and Lillian Gish found the stage role of a lifetime. “Dorothy and I went to see the New York production of Life With Father, starring Howard Lindsay and Dorothy Stickney,” Lillian wrote in her autobiography. “After the performance I said: ‘This is the play we’ve been waiting for to take through America.’” Lillian predicted the popular play would be a perfect showcase for all the people who had seen the hundreds of films featuring Mary Pickford, Dorothy, and herself. She was introduced to Lindsay backstage, and immediately surprised the producers with her enthusiastic desire to head the first company to go on the road, with Dorothy taking the same part for the second road company, and the movie rights for Mary Pickford. Pickford did not make the film version, but the Gish sisters took the two road companies on extensive tours. Another stage success later in Gish's career was The Magnificent Yankee, which ran on Broadway at the Royale Theatre during the first half of 1946. Lillian in her pictorial book Dorothy and Lillian Gish repeats John Chapman's comments about her sister's work in that production: "'Miss [Dorothy] Gish and Mr. Calhern give the finest performances I have ever seen them in. She is a delight and a darling.'"

Television in the 1950s offered many stage and film actors the opportunity to perform in plays broadcast live. Dorothy ventured into the new medium, appearing on NBC's Lux Video Theatre on the evening of November 24, 1955, in a production of Miss Susie Slagle's. She and Lillian had previously performed that play together on screen, in Paramount Pictures' 1945 film adaptation.

"The truth is, that she did not know what she really wanted to do," wrote her sister, Lillian, in her autobiography. "She had always had trouble making decisions and assuming responsibilities, in some ways she had never grown up. She was such a witty and enchanting child that we enjoyed indulging her. First Mother and I spoiled her and later Reba, her friend, and her husband Jim. Reba called Dorothy 'Baby' and so did Jim. With the best intentions in the world, we all helped to keep her a child."

From 1930 until her death, she only performed in five more movies, including Our Hearts Were Young and Gay (1944), which was a hit for Paramount. Director Otto Preminger cast Dorothy in his 1946 film, Centennial Summer, and Mae Marsh appears in the film in one of her many bit parts. In the 1951 release The Whistle at Eaton Falls, a film noir drama film produced by Louis de Rochemont, Dorothy portrays the widow of a mill owner. On television during this period, she also made several appearances in anthology television series. Her final film role was in 1963 in another Otto Preminger production, The Cardinal, in which she plays the mother of the title character.

Dorothy Gish married only once, to James Malachi Rennie (1890–1965), a Canadian-born actor who co-starred with her in two productions in 1920: Remodeling Her Husband, directed by sister Lillian, and in the comedy Flying Pat. In December 1920, the couple eloped to Greenwich, Connecticut, where they wed in a double ceremony in which Gish's friend, actress Constance Talmadge, also married Greek businessman John Pialoglou. Gish and Rennie remained together until their divorce in 1935. Dorothy never married again

Gish died aged 70 in 1968 from bronchial pneumonia at a clinic in Rapallo, Italy, where she had been a patient for two years to treat hardening arteries. Her sister Lillian, who was filming in Rome, was at her bedside. The New York Times reported the day after her death that the United States consulate in Genoa was making arrangements to cremate "Miss Gish's body" for return to the United States. The ashes were later entombed in Saint Bartholomew's Episcopal Church in New York City in the columbarium in the undercroft of the church. Lillian, who died in 1993, was interred beside her.

In recognition of her contributions to the motion picture industry, in 1960 Dorothy Gish was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6385 Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles.

The (since renamed) Gish Film Theatre and Gallery of Bowling Green State University's Department of Theatre and Film was named for Lillian and Dorothy Gish and was dedicated on that campus in 1976.

#dorothy gish#silent era#silent hollywood#silent movie stars#classic hollywood#golden age of hollywood#classic movie stars#1910s movies#1920s hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood#1950s hollywood#1960s hollywood

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queen of HelEdit

Hela often tried to expand her power to the dead who dwell in Valhalla as well. These attempts often brought Hela into conflict with Odin or his son Thor. She once appeared to Thor while he was on the verge of death after battling the Wrecker, who knocked a building onto him while he was depowered.[3] However, she failed to tempt Thor into entering Valhalla, despite an image of one that dwelled in Valhalla.[4]

Later, she stole a portion of the sleeping Odin's soul while he was on the Sea of Eternal Night due to Loki planning to take over Asgard, thus creating a powerful entity known as Infinity.[5] Hela then unleashed Infinity upon the universe. Infinity even took control of Odin.[6] Hela slew Thor, who was restored to life by the sacrifice of her servant, the Silent One.[7] Hela was then slain by Odin to save Thor, but then returned to life by Odin after being convinced by Thor to restore the natural balance of life and death. Hela slew Thor after tracking him down by putting humans in danger, but restored him to life after Sif offered to die in his place.[8]

Hela later battled the Olympian Death-god Pluto for the right to claim Odin's soul, as Odin had been killed by the monster Mangog.[9] As a result, Hela restored Odin to life to prevent Pluto from claiming him.[10] Some time later, Hela confronted Thor.[11] Some time after that, she confronted Odin.[12] She then plotted with Loki to bring about Ragnarök by slaying the god Balder then attacking Asgard. She summoned Volla's spirit before this to tell her and Loki about Ragnarok, after which she prepared an army of monsters to attack Asgard. However Odin used his powers to prevent Balder dying.[13] Later Balder was restored after the Asgardian's death and resurrection battling the Celestials.[14]

Hela then summoned the Valkyrie to aid in a war against Ollerus, while Hela encountered the other Defenders.[15] Hela was then forced to join a conspiracy of Loki and Tyr against Odin.[16] She also unwillingly entered an alliance with the death-gods of other Earth pantheons, joining their realms together to create a vast hell. As a result, she was destroyed and devoured along with other Death-gods by Demogorge the God-Eater, though it happened to her last, who was wakened by the joining, but was restored to life with Demogorge's defeat.[17]

Hela later allied with Malekith, and took souls of Earth mortals to Hel using special food of the faerie.[18] She then appeared in Asgard to claim Odin's soul, but was driven off by Thor.[19] She encountered the X-Men and New Mutants in Asgard. She appeared to claim Wolverine's soul, but was driven off by the X-Men and Mirage.[20] Hel was then invaded by Thor, Balder, the Executioner, and the Einherjar to rescue the captive mortal souls. Hela wrestled Thor for the captive mortal souls.[21] Hela raised an army of the dead to stop Thor's escape from Hel.[22]

During this fight with Thor, in revenge for his defiance and invasion of her realm, Hela cursed Thor with a dark form of eternal life, making him incapable of dying while also making his bones weak and brittle so that they would break more easily and wouldn't heal from the damage inflicted, Hela reflecting in satisfaction at the image of Thor coming to long for death while she refuses to grant it.[23] Hela then contested against Mephisto who attempted to possess Thor's soul.[24] Thor creates special mystical armor as protection,[25] but after battling and defeating the Midgard Serpent, his body is pulverized into jelly.[26] Thor eventually forces Hela to lift the curse by using the Destroyer as his host body to invade Hel, forcing Hela to restore his body to life and health before he could destroy her.[27]

From time to time, Odin would enter a magical sleep in order to bolster his powers. It was during one of these sleeps that Hela made a plan for power. She corrupted the Valkyries, mentally and physically, transforming them into fire-demons. This also included Danielle Moonstar, of the New Mutants, who was on Earth at the time, who Hela set against the New Mutants.[28] Dani and her team were eventually brought over to Asgard. Hela sent the Valkyries against the dwarves and New Mutants in Asgard.[29] The New Mutants skirmished with Hela's forces again and again, even rescuing the prisoner Hrimhari, a wolf-prince from a far away land. Hela forced the dwarf Eitri to forge a sword of Asgardian metal "uru". One of Hela's spells split the group. This resulted in a more efficient recruitment of resistance force, which included the Warriors Three. Hela sent Mirage to kill the sleeping Odin. While most of the Asgardian forces battled Hela's soldiers, the mutants ventured to Odin's very bedchambers, saved Odin's life and foiled Hela's plans. Hela was defeated when the uru sword was destroyed.[30]

Conflict with various forces brought Bruce Banner, a.k.a. the Hulk, and Agamemnon, the leader of the Pantheon, to Hela's realm. After an undetermined time fighting Hela's skeletal forces, Agamemnon pleaded, based on a vaguely hinted upon relationship, to allow the two to leave. Hela relented, reluctantly.[volume & issue needed]

Hela on EarthEdit

Hela was awakened from her mortal guise after Ragnarök by Thor, albeit due to Loki's machinations.[31] She now lives in Las Vegas, maintaining a lair where she can feed on the souls of random unlucky people, and agrees to use her powers to aid Loki in bringing him back in time to Asgard to complete his own sinister plans for Asgard.[32]

She is seen attending a meeting with Mephisto, Blackheart, Satannish and Dormammu about a disturbance created by the newly resurrected Magik, who is looking for the soulsword and the original Bloodstone amulet. Belasco's daughter, Witchfire appears during the meeting and reveals she is now the current owner of the original amulet and vows to take her father's place as ruler of Limbo and seat at their table.[33]

When Norman Osborn attempts to subdue the X-Men, Cyclops sends Danielle Moonstar to Las Vegas where she approaches Hela for a boon. Hela warns her that the price of the boon is a heavy one, but Dani accepts, requesting "a new ride home and a big ol' sword."[34] Later, Hela is summoned to Utopia by Hrimhari to save a pregnant Rahne and their child, which is neither human nor mutant. Faced with a moral dilemma, to save his child or Rahne; Hrimhari asks Hela to restore Elixir to full health so Elixir may heal them both and to take him instead. Hela agrees and takes Hrimhari away.[

1 note

·

View note

Text

How Will New York Abstract Expressionism Be In The Future | new york abstract expressionism

New York Art Collector – Discovering Excellence: Albert … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Biography of Paul Jenkins | Widewalls – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

The Women Who Helped Create Abstract Expressionism – The New York Times – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

MoMA and Abstract Expressionism | AB EX NY – YouTube – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Conrad Marca-Relli Abstract Expressionism-New York School … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

‘Abstract Expressionist New York’ at MoMA – The New York Times – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Albert Kotin- Abstract Expressionism-New York School Art – Early … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Abstract Expressionism & the New York School | Khan Academy – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Daniel Belasco: Becoming Al Held: Abstract Expressionist Paintings … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

PPT – American Abstract Expressionism “The New York School … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Norman Lewis | ART Inspiration | Pinterest | Norman … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

45x60cm acrylics, enamel and pastels on board, in sept. 2018 by mike esson – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Abstract Expressionism: Time, Intention, Conservation, and Meaning … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Abstract Expressionist New York at MOMA – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Cavalier Galleries Blog: The New York School: Abstract … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

abstract detail 120x90cm acrylics, latex and pastel on glossy paper, in november 2018 by mike esson – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Abstract Expressionist New York @ MoMA | Stephanie Nikolopoulos – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

REQUIEM FOR A BIKE – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

acrylics, enamel, collage and pastel on board, 103x85cm in june 2018 by mike esson – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

What is Abstract Expressionism? – YouTube – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Peterdi, Gabor (1915-2001) – 1961 Desert I (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC) – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

The Arts File: How Abstract Expressionism Took Off in New York … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

Abstract Expressionism – Mark Rothko – Irving Sandler – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

New York boat – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

New York Skyline Abstract Painting by Irina Rumyantseva | Artmajeur – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

192 best American Abstract Expressionism images on … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

27 Female Abstract Expressionists Who Are Not Helen Frankenthaler … – new york abstract expressionism | new york abstract expressionism

from WordPress https://americanartist.club/how-will-new-york-abstract-expressionism-be-in-the-future-new-york-abstract-expressionism/

0 notes

Audio

Given Joe Barbera’s longtime interest in the floorboards and the footlights, I thought it interesting to share this radio adaptation of the Bette Davis farce about the theater and the “stage door Janes” following it--only this time, with the irrepresible Tallulah Bankhead joining The Theater Guild.

(BTW, Theater Guild on the Air, originating from The Belasco Theater on Broadway, was also known as The United States Steel Hour for its longtime sponsors. Take especial note of Norman Brockenshire’s deep, resonant voice as the announcer and George Hicks as “The Voice of Steel” during the breaks.)

0 notes

Text

Norman Bel Geddes logo. Image from Wikipedia.

Norman Bel Geddes, circa 1925. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

For October’s reference library update, Driving For Deco brings you a career profile of industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes (1893 – 1958). The article appeared in the July, 1930 issue of Fortune magazine. Bel Geddes began his career as a set and stage designer working for the Metropolitan Opera. In the 1920’s shows he designed included The Miracle and Fifty Million Frenchmen. In the mid 1930’s he would design the set for Sidney Kingsley’s play Dead End.

The Miracle, New York production 1924. Set by Norman Bel Geddes. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Norman Bel Geddes set for Dead End, 1935. Sidney Kingsley’s Pulitzer Prize winning play at the Belasco Theater. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

Turning from the theatre in the late 1920’s Bel Geddes ventured into the brand new field of industrial design. He achieved new fame by redesigning many standard products. Ranging from kitchen appliances, to cars and other forms of transportation, to homes and factories, nothing was too small or too large for Bel Geddes to tackle. In 1932 he authored the book Horizons in which he outlined his theories and ideas.

Horizons by Norman Bel Geddes, 1932. Image from abebooks.com

Today, original 1932 editions of this book are rare and can sell between $250.00 and $950.00.

Norman Bel Geddes ideas for planes, ocean liners and cars went far beyond anything of his time. He took streamlining further than any of his contemporaries. Bel Geddes liked to push limits knowing these designs would never materialize.

Norman Bel Geddes Airliner No. 4 (1929-1932). Image from Keiththomsonbooks.com

“Whale” Ocean Liner designed by Norman Bel Geddes, 1932. Image from oobject.com

Locomotive No. 1 by Norman Bel Geddes, circa 1932. Image from oobject.com

Norman Bel Geddes Motor Car No. 9, circa 1932.

Of all the designs that Norman Bel Geddes created, three are most accessible to collectors today. The 1938 Soda King Syphon bottle, Revere’s magazine stand and the iconic “Manhattan” cocktail set are available with a good deal of cash.

Bel Geddes – Paxton Soda King, White. 1938

Norman Bel Geddes’ magazine stand for Revere. Image from einnasirrod.com

The Manhattan cocktail set for Revere designed by Norman Bel Geddes. Image from the Museum of Fine Arts of Houston.

Futurama brochure, 1939. Image from oldcarbrochures.com

The best showcase for industrial designers in the 1930’s was the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Bel Geddes created its most popular exhibit, General Motors, Futurama. This massive display provided a glimpse into 1960 America in a simulated coast-to-coast airplane flight. Massive highways with radio controlled cars provided access to cities with different levels for automobiles and pedestrians. There would also be plenty of green space to spend leisure time. Industrial zones would be a good distance away from residential neighborhoods. Many of the ideas that Bel Geddes designed for Futurama would come to fruition in the 1950’s and later.

Norman Bel Geddes General Motors Pavillion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Image from The New York Times.

#gallery-0-6 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-6 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-6 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

Part of the massive Futurama exhibit. Image from NYPL Digital Collections.

The city of 1960 as conceived by Norman Bel Geddes for Futurama. Image from Skyscraper.org

To read the Fortune article profiling Norman Bel Geddes industrial design career, click on the cover below.

July, 1930 Fortune Magazine

Anthony & Chris (The Freakin’, Tiquen’ Guys)

Reference Library Update – Bel Geddes

#"Whale" Ocean Liner#1939#Airliner No. 4#Futurama#Industrial Design#Locomotive No. 1#Manhattan Cocktail Set#Motor Car No. 9#New York World&039;s Fair#Norman Bel Geddes#Revere Magazine Stand#Set Design#Soda King

0 notes

Text

Violet Ethelred Krauth (October 17, 1913 – November 9, 2006), better known by the stage name Marian Marsh, was a Trinidad-born American film actress and later an environmentalist.

Violet Ethelred Krauth was born on October 17, 1913, in Trinidad, British West Indies (now Trinidad and Tobago), the youngest of four children of a German chocolate manufacturer and, as noted by encyclopaedist Leslie Halliwell in his book The Filmgoer's Companion, his French-English wife.

Owing to World War I, Marsh's father moved his family to Boston, Massachusetts. By the time she was 10, the family had relocated to Hollywood, California. Her older sister, an actress who went by the name of Jean Fenwick, landed a job as a contract player with FBO Studios. Another sister, Harriet, was a chorus girl who danced in Earl Carroll's Vanities. She changed her name to Jeanne Morgan.

Marsh attended Le Conte Junior High School and Hollywood High School. In 1928 she was approached by silent screen actress Nance O'Neil, who offered her speech and movement lessons, and with her sister Jean's help, she soon entered the movies. She secured a contract with Pathé, where she was featured in many short subjects under the name Marilyn Morgan.

She was seen in small roles in Howard Hughes's classic Hell's Angels (1930) and Eddie Cantor's lavish Technicolor musical Whoopee! (1930). The part in Whoopee! resulted from Marsh's visit to a film studio with her sister. Not long afterwards, she was signed by Warner Bros. and her name was changed to Marian Marsh.

In 1930, at age 17, Marsh had the female lead in Young Sinners, a play at the Belasco Theater. A contemporary news article reported that she "has scored a distinct hit" in her first stage production.

In 1931, after appearing in a number of short films, Marsh landed one of her most important roles in Svengali opposite John Barrymore. Marsh was chosen by Barrymore for the role of Trilby.[2] Barrymore, who had selected her partly because she resembled his wife, coached her performance throughout the picture's filming. Svengali was based on the 1894 novel Trilby written by George du Maurier. A popular play, based on the book, also titled Trilby, followed in 1895.

In the film version, Marsh plays the artist's model Trilby, who is transformed into a great opera star by the sinister hypnotist Svengali. The word "Svengali'" has entered the English language, defining a person who, with sometimes evil intent, tries to persuade another to do what he desires.

Marsh was awarded the title of WAMPAS Baby Stars in August 1931 even before her second movie with Warner Brothers was released. With her ability to project warmth, sincerity and inner strength on the screen along with critical praise and the audience's approval of Svengali, she continued to star in a string of successful films for Warner Bros., including Five Star Final (1931) with Edward G. Robinson, The Mad Genius (1931) with Barrymore, The Road to Singapore (1931) with William Powell, Under 18 (1932) with Warren William, Alias the Doctor (1932) with Richard Barthelmess, and Beauty and the Boss (1932) with Warren William.

In 1932, in the midst of a grueling work schedule, Marsh left Warner Bros. and moved to RKO, where she made Strange Justice (1932) with Norman Foster and The Sport Parade (1932) with Joel McCrea. After that, she took several film offers in Europe that lasted until 1934. She enjoyed working in England and Germany, as well as vacationing in Paris. While in England, she appeared in the musical comedy film Over the Garden Wall (1934). Back in the United States, she appeared as the heroine Elnora in a popular adaptation of the perennial favorite A Girl of the Limberlost (1934).

In 1935, Marsh signed a two-year pact with Columbia Pictures. During this time, she starred in such films as The Black Room (1935) regarded as one of Boris Karloff's best horror films of the decade, Josef von Sternberg's classic Crime and Punishment (1935) with Peter Lorre, wherein she played the sympathetic prostitute Sonya, Lady of Secrets (1936) with Ruth Chatterton, Counterfeit (1936) with Chester Morris, The Man Who Lived Twice (1936) with Ralph Bellamy, and Come Closer, Folks (1936) with James Dunn.

When her contract expired in 1937, Marsh once again freelanced, appearing steadily in movies for RKO Radio Pictures, where she made Saturday's Heroes (1937) with Van Heflin, and for Paramount Pictures, where she played a young woman caught up in a mystery in The Great Gambini (1937). She appeared with comic Joe E. Brown in When's Your Birthday? (1937), and Richard Arlen in Missing Daughters (1939). In the 1940s, Marsh played Wallace Ford's secretary in Murder by Invitation (1941) and the self-willed wife in Gentleman from Dixie (1941). In her last screen appearance, Marsh portrayed the daughter of an inventor in the comedy/mystery House of Errors (1942), which starred Harry Langdon.

In the late 1950s, she appeared with John Forsythe in an episode of his TV series Bachelor Father and in an episode of the TV series Schlitz Playhouse of Stars before retiring in 1959.

Marsh married a stockbroker named Albert Scott on March 29, 1938, and had two children with him, Catherine Mary Scott (1942-2018) and Albert Parker Scott Jr. (1944-2014). They divorced in 1959. In 1960, Marsh married Cliff Henderson, an aviation pioneer and entrepreneur whom she had met in the early 1930s. They moved to Palm Desert, California, a town Henderson founded in the 1940s.

In the 1960s, Marsh founded Desert Beautiful, a non-profit all-volunteer conservation organization to promote environmental and beautification programs.

Cliff Henderson died in 1984 and Marsh remained in Palm Desert until her death.

In 2006, at age 93, Marsh died of respiratory arrest while sleeping at her home in Palm Desert. She is buried at Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City, California.

October 17, 2015, was designated as Marian Marsh-Henderson Day by the city of Palm Desert, California.

5 notes

·

View notes