#shigajiku

Photo

Early Spring Landscape, Shūsei, Before 1459, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Japanese and Korean Art

two figures in pavillion on stilts in water; dark rock coveriing much of pavillon; pine trees and larger rock formations in background; bridge through haze at center; boat at L; inscription Beneath impossibly tall pine trees and distant, misty peaks, two men round the bend of a path at lower right. They make their way toward a thatched pavilion nearby, where two more men sit and gaze at fishermen rowing a boat on the river. Above, a poetic inscription reinforces the theme: early spring in an idyllic mountain retreat. South of the river and north of the river, the snow is clearing. Mountains spew forth rosy clouds, springtime colors are fresh. Travelers remove their shoes, though the going is still rough. Opening the window, seated guests enjoy the splendid view. Water flowing beneath the bridge rings like chimes of jade. At the eaves, the wind in the pines tunes its stringless lute. But why is that leaf of a boat moored beside the cliff' It must be a craft for roving ten thousand miles away. Such combinations of a painting with one or more poetic inscriptions are called shigajiku (literally “poem-painting scroll”). They are collaborative works created by groups of Zen monks and lay practitioners, talented poets, calligraphers, and painters who lived not in some serene countryside but in the noisy, crowded spaces of urban monasteries.

Size: 29 3/8 × 10 7/8 in. (74.61 × 27.62 cm) (image) 57 × 14 3/4 in. (144.78 × 37.47 cm) (mount, without roller)

Medium: Ink and light color on paper

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/99427/

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

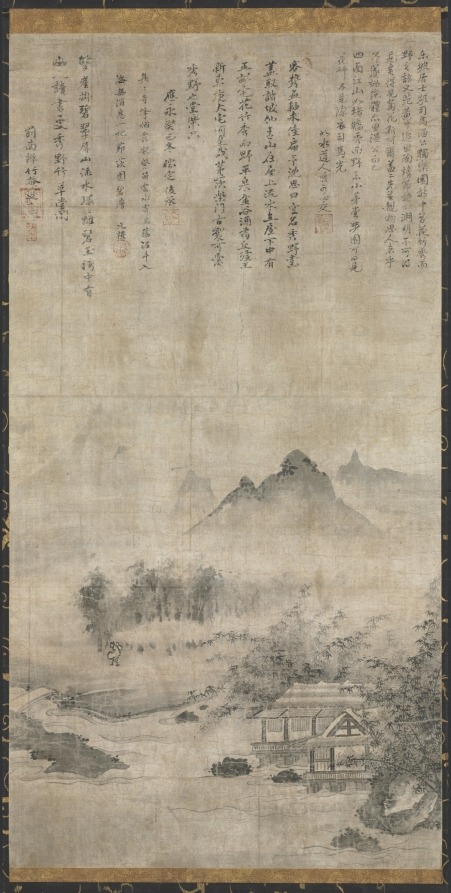

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

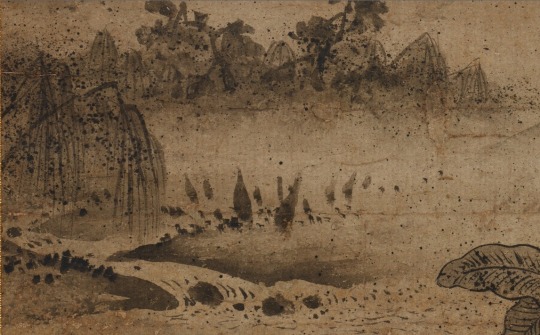

Anónimo - Lluvia nocturna sobre los plátanos

Lluvia nocturna sobre los plátanos

Anónimo (la pintura)

Período Muromachi

1410

Japón

Rollo colgante, tinta sobre papel 95,9 x 31,0 cm

Múltiples inscripciones

Comentario en emuseum.jp:

Sobre la pintura hay elogios escritos por catorce personas distintas. Doce son monjes zen de la escuela Gozan: Taihaku Shingen, Shukuei Souban, Motonaka Masanobu, Mubun Banshou, Isho Tokugan, Kengan Genchu, Ichu Tsujo, Gakuon Suzo, Keisou Hikosho, Gyokuen Bonpou, Seiin Shunjou y Genchu Shugaku. También hay un comandante militar, Yamana Tokihiro, y un diplomático coreano, Ryouju.

Desde finales del período de la Corte Sur y Norte (comienzos del período Muromachi) la producción de shigajiku (lit. rollo con poesía y pintura) abundó en los templos zen en especial de la escuela Gozan, que se caracteriza por un rollo colgante con un número de poemas chinos o prosa. De acuerdo a una de las inscripciones, un joven monje llamado Ikkai Kenpu compuso un poema titulado Shuu-u Basho (Bananero japonés en la lluvia de otoño). Esta pintura se hizo para expresar el sentimiento de este poema, y sus compañeros compusieron otros poemas para dárselos como regalo. Solo una pieza de shigajiku anterior a esta permanece, Saimon Shingetsuzu (Luna nueva sobre el portal).

Los pequeños puntos en el primer plano y en el plano medio se hicieron con la técnica fukizimi (soplar pigmentos a través de un tubo), y representan la lluvia cayendo sobre las hojas del plátano. La montaña principal en el plano medio y los árboles y pastos en la costa muestran cierta influencia del estilo de Beihou Sansui que pertenecía a la escuela Toukyo (escuela de la dinastía Yuan en China).

Detalle del río y sauces:

Detalle de los plátanos:

0 notes

Photo

From Japanese Art by Joan Stanley-Baker: “In the late fourteenth century, reflecting the secularization among Chan monks in China and Korea where literary accomplishment replaced spiritual quest, a form of poem painting (shigajiku) evolved; in it, landscape painting complements the group of poems composed during a gathering of literary monks. It had been largely the product of monastic literary associations until a Shōgun, probably Yoshimitsu, specifically ordered such a work to be produced as a backdrop screen for his dais. He asked distinguished monks from Kyoto to compose poems, and commissioned Josetsu (fl. early fifteenth century) of his Shōkokuji monastery to paint in the ‘new style’ (of the Southern Song academician and Chan painter Liang Kai). The theme of the painting was the Zen riddle on catching the slippery catfish with the smooth-skinned gourd. Josetsu’s compelling work is largely monochrome, with a touch of red to accent the gourd. The Liang Kai manner can be seen in the hooked and angular lines of the drapery. The sweep of the bank is remarkable, from the dense confluence of streams on the left to the opening up to grand dissolution on the right (a reversal of the usual narrative flow from right to left). The gentle curves of bank, bamboo, catfish, gourd and flowing water are offset by the bristling intensity of the reeds on the right, and by the extraordinary face of the aspirant. This screen was subsequently remounted in its present hanging scroll format.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

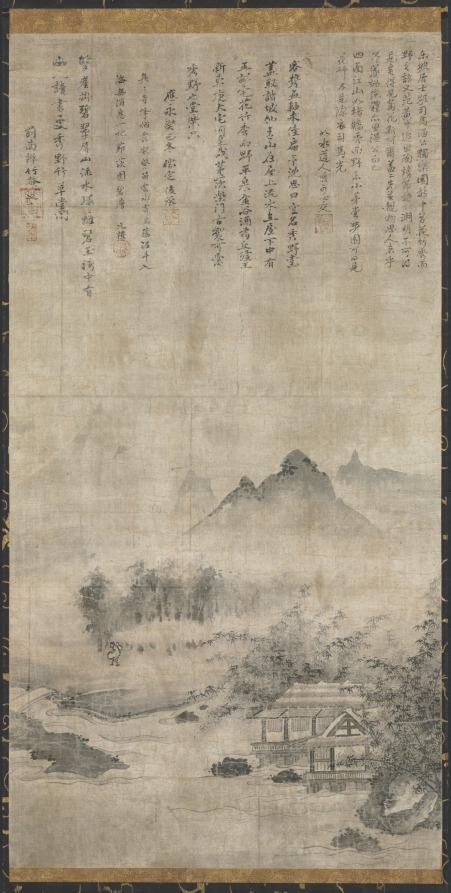

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Landscape, c. 1414, Cleveland Museum of Art: Japanese Art

In the Muromachi period, Zen clerics often mounted their original Chinese-style poems above an ink painting to make a hanging scroll called a shigajiku. In the inscription here, Japanese Zen clerics quoted from essays on Sima Guang (1019–1086) by the Chinese Song dynasty literatus Su Shi (1037–1101). They interpreted the studio surrounded with bamboo as a metaphor for the garden of Sima, the Song dynasty scholar-official who, in imitation of the Tang poet Bai Juyi, enjoyed the garden in isolation during his exile in Luoyang.

Size: Painting only: 102.8 x 54 cm (40 1/2 x 21 1/4 in.); Including mounting: 182.9 x 60.7 cm (72 x 23 7/8 in.)

Medium: hanging scroll; ink and color on silk

https://clevelandart.org/art/1985.111

1 note

·

View note