#they have to take giffing in browser mode away from me before i fry this computer to a jerky strip

Text

We gonna have to call this in, Rust.

Oh, we don't wanna do that.

#he was at his most lesbian here#second only to the lone star-daisy ring scene cc 2012. spitting out metal in a 4 week old shirt. i know she'd fist me in a pickup truck#who was it that said 'you can see his pussy frothing' in the tags? anyway so real for that#true detective#rust cohle#marty hart#h#true detective s1#my grounding technique is watching the sweat dry on his ripped top✊😔#they have to take giffing in browser mode away from me before i fry this computer to a jerky strip#some nights are like im rewriting blood meridian im eating pizzolatto's auteurism and spitting it out. other nights you ask?#well other nights are for looking at deadbeat cop yuri#🧃

488 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Passagio: Understanding Registers Within Laryngeal Vibratory Mechanisms

Preface

I've been studying singing for around 9 years now, and the concept of my passagio has always been something very nebulous to me. While I may have had a surface level understanding of the difference between registers, internally I still understood them in a very unnuanced way. Falsetto was just some magical upper setting that somehow felt different and allowed me to achieve higher pitches, for instance, but I never understood the process at a granular level.

When starting at university, something became very apparent very fast: I didn't know my way around my voice as well as I thought I did. Suddenly I was singing with an amplified band for the first time, and it felt like all those years of classical and musical theatre training went out the window as I was left uncertain of how to project my voice over the band. I couldn't hit high notes that under any other circumstances would have sat comfortably in my range, and so had to find workarounds like taking a lower harmony while a female vocalist covered what I was actually supposed to be singing.

This was, of course, treating the symptom rather than the cause. As a singer in the real world, an employer isn't going to accept you rearranging their music to suit your inabilities. In order to improve this, I spent several months researching what constitutes phonation, register, and passagio at the base level. The following is what I have discovered.

Introduction

A singer's "break" or "passagio" is a concrete phenomenon with a roster of very vague explanations. A singing teacher might refer to it as "moving between your chest voice and your head voice", but what's meant by this varies wildly depending on parameters such as the singer's age, sex, etc. These registers are defined solely by how they feel to the singer, which is by no means a consistent metric. In this essay I will attempt to explain the concept of a passagio within a consistent, measurable, scientific framework, with the intent of better understanding how to traverse it in a musical context.

Before we can understand what constitutes a passagio, however, we must first understand how the voice is produced.

Components of an Instrument

All instruments consist of at least three main components. A motor, a vibrator, and a resonator. The motor can be defined as any sort of external influence that powers the vibrator, which then oscillates at pitch, and is amplified by the instrument's resonator.

The dilemma that we singers inevitably face is that we have no convenient visual interface for how our instrument produces sound; everything is internal. While it's obvious to a guitarist, for instance, that their fingers power their strings, whose vibrations are amplified by the instrument's resonant body - we have to deal with a lot of very complicated and unintuitive language for a process that feels very intuitive and natural.

So what are the components of our instrument?

Our motor, obviously, is our lungs - which are supported by a large muscle in the abdomen called the diaphragm.

Our vibrator is our vocal folds - two flaps of flesh and mucous, located in our larynx, (colloquially known as our "voice box"). (Pictured below[1], in abducted and adducted postures respectively)

Our resonator essentially boils down to "everything", but more specific examples include our nasal cavities and chest.

And finally, our articulator consists of our mouth. Our lips, teeth, tongue, soft palate, etc. all contribute to our filtering of sound into language. The same carries over to singing.

Phonation

Phonation is the process of producing sound by way of the vocal folds. The cycle of sound production begins with the folds more or less closed, pressing against each other. As pressure is applied by airflow from the lungs, the folds are blown apart for a moment, before returning to their closed setting. This, fundamentally, is the process of phonation. This oscillation occurs hundreds of times a second - producing a pitched sound.

For the purposes of this essay, we will consider the vocal folds to consist of three main components: the vocalis muscle, connective tissue, and mucosal layer.

Pitch

In any acoustic vibration, the pitch is dictated by the mass of the thing doing the vibrating. Since it takes more energy to move something of a higher mass, the more massive a medium is, the lower the frequency of its vibration will be.

Since we can't magically manipulate the mass of something without violating the laws of physics, we have to compromise. What we're able to do is manipulate how much mass is participating in the vibration. A guitarist, for instance, does this by pressing a string against a fret, changing the stopping point of the string and thus reducing how much mass is participating in the vibration.

The vocal folds operate under the same principle. The vocalis muscles (which make up the majority of the body of the vocal fold) and cricothyroid muscles pull against each other, thus providing tension and thinning and thickening the folds as required. Thin, tense folds will vibrate at a higher frequency than long, loose folds.

Laryngeal Vibratory Mechanisms

With all of that out of the way, let's discuss how this applies to one's Passagio.

As the frequency of the vibration goes up, the physical limits of the components of the vocal folds are reached in succession. We refer to these as Laryngeal Vibratory Mechanisms (LVMs) - four different settings of vocal fold vibration that encompass what we colloquially consider to be “registers”.

The LVMs are numbered 0-3. (The following images are intended to be animated GIFs. Direct links to the images are available in the bibliography if they do not appear correctly on your browser.)

Mechanism 0 can be referred to scientifically as "pulse phonation" and colloquially as "vocal fry". Essentially, what's happening here is the majority of the vocal folds are vibrating against each other at a low frequency.

Mechanism 1 is where our voices normally sit in day-to-day use: it covers the same ground as what would be referred to as “chest voice”. The full body of the folds are vibrating - it can be thought of as speech quality. (Pictured below [2a])

Mechanism 2 (pictured below[2b]) can be thought of as head voice, falsetto, etc. In this setting, the vocalis muscles (red) and connective tissue (yellow) are both rigid, and only the mucosal layer (orange) is vibrating. This is why we experience a break - we're literally shifting to a different mode of vibration all together.

Mechanism 3 relates to the whistle register, where even the mucosal layer is rigid, and the sound is produced under the same principle as whistling with our lips.

A more intuitive parallel for this would be to imagine this process in the context of drumming. If a drummer is playing a relatively low tempo pulse, they can get away with using their arm in the motion (M0), but as the tempo is raised it no longer becomes energy-efficient to do this. At this point, the arm becomes rigid and the motion is carried out via the wrist (M1). The same limit is reached here and it becomes too tiring to move so much mass for such a small motion, so the drummer switches to finger control (M2), allowing them to play much faster passages.

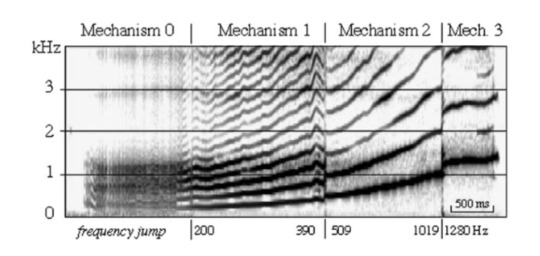

Below is a Sonogram of an ascending vocal glissando, showing the four natural “breaks” or transitions between mechanisms[3].

Registers Within the LVM Framework

The temptation here is to think that LVMs are a complete replacement to the idea of registers; they’re not, they’re just a standardised way of talking about the voice.

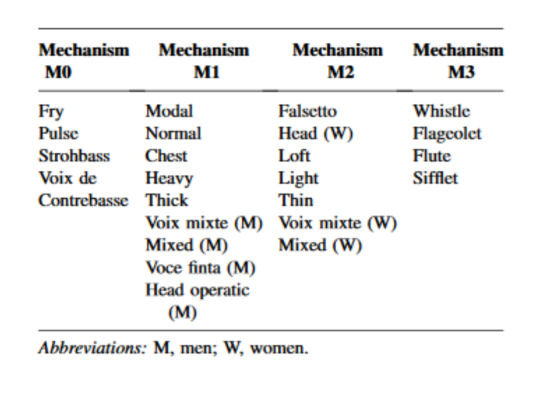

Registers definitely still have a place in our vocabulary, it’s just important to not conflate them with Mechanisms. For instance, it’s possible to switch register, while still remaining within the same LVM. Pictured below is a table of the four mechanisms and what registers fit within them[3].

Exercises

Interesting as it may be, the passagio is often an annoyance that we can only really cheat around. The only way to navigate it fluently is to have a developed understanding of how it works and where it sits in your range.

In my case, I found it helpful to learn how to cheat my way past the passagio by skipping past it using an unvoiced consonant (a consonant wherein the vocal folds aren’t vibrating). Doing octaves over the passagio on “sha”, “sa”, “tha”, “ti”, etc. is a very helpful way of developing this. The more consonants you practice with, the easier it will be to use this technique intuitively in a song.

If you must sing over your passagio, there are ways to make the process a little more forgiving. When the vocal folds vibrate, we can think of them as having what’s called an open and closed quotient. Essentially what these refer to is the ratio of how long the vocal folds are closed, vs how long they spend open during the phonation cycle (this is similar to the concept of a “duty cycle” in electrical oscillations). A high closed quotient sounds buzzy whereas a high open quotient sounds smooth and almost breathy at higher levels. What we want is to sing with a high open quotient and sing confidently through the passagio, which lessens the dramatic timbral shift of the transition (although it doesn’t eliminate it).

In Conclusion

Learning about LVMs has provided an invaluable boost to my singing ability. I’m much more confident in and aware of my technique, because I now understand the processes at the fundamental level. Going forward, I’d like to make more singers aware of this system of classification - as it’s not something we tend to learn about in music education. If nothing else, it’s just very, very interesting - and that’s as good a reason to learn about something as any.

Bibliography

[1] Voicedoctorla.com. (2018). Vocal Nodules / Nodes. [online] Available at: https://voicedoctorla.com/voice-disorders/vocal-nodules-nodes/ [Accessed 23 May 2018].

[2] En.wikipedia.org. (2018). Vocal folds. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vocal_folds#Oscillation [Accessed 23 May 2018].

*note: I’m aware of the issues that come with citing Wikipedia as a source, but the two images in particular that I borrowed from them for use in this essay are a perfect visualisation of the point I’m trying to make, and I thought it a shame to die on the hill of not citing Wikipedia, rather than to produce a piece of work that A) I’m proud of and B) is readable/understandable. My main points come from other, more reliable sources.

[2a] M1 Oscillation - direct image link: https://i.imgur.com/B3Nc2xr.gif

[2b] M2 Oscillation - direct image link: https://i.imgur.com/2rMR67w.gif

[3] Roubeau, B., Henrich, N. and Castellengo, M. (2009). Laryngeal Vibratory Mechanisms: The Notion of Vocal Register Revisited. Journal of Voice, 23(4), pp.425-438.

[4] /u/GrafKarpador (2018). what happens physiologically when i change between two pitches? what should be changing, and what should not? • r/singing. [online] reddit. Available at: https://www.reddit.com/r/singing/comments/86i0tl/what_happens_physiologically_when_i_change/dw5d952/?context=0 [Accessed 23 May 2018].

0 notes