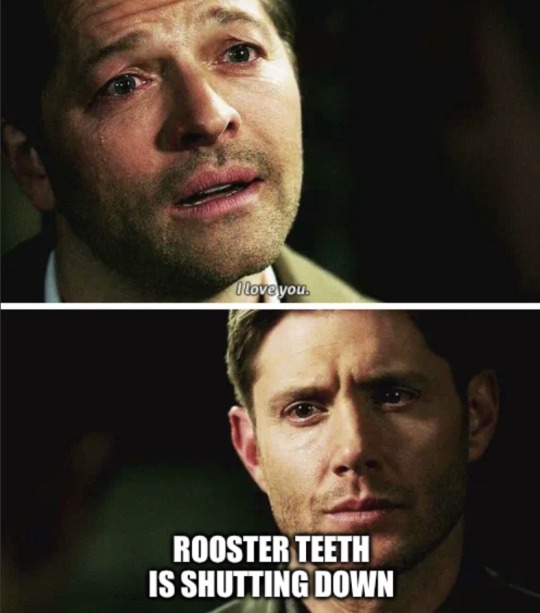

#warner media on the other hand…..rot <3

Text

well….it finally happened

#rip rt#the good times were certainly good <3#rt#roosterteeth#rooster teeth#honestly this is how i’m finding out it was officialy rooster teeth and not one word#if anyone doesn’t read the article but reads my tags (??) it looks like only the podcasts are carrying on for the time being#they’re shopping around rwby and shows like that and the roost which is the podcast side of things but otherwise#also apparently there’ll be a stream on the rt site tomorrow talking about it if anyone is interested#idk this sucks#be good to the people who were still there they deserve it#warner media on the other hand…..rot <3

4K notes

·

View notes

Link

Robert Zemeckis’s zany, brilliant Who Framed Roger Rabbit, released 30 years ago on June 22, 1988, is remembered by the many who love it as a film ahead of its time.

Its gathering of dozens of cartoon all-stars in the same place now feels like a nod toward a future when all pop culture would be thrown into a blender all of the time, and its use of computers to blend real actors with animated characters remains jaw-dropping in both its complexity and its effect. If nothing else, the movie’s star, Bob Hoskins, should be properly remembered for perfecting a whole new style of acting that has only come to take over big-budget studio movies more and more. (Josh Spiegel has much more about this idea over at /Film.)

And Roger Rabbit was the rare box-office hit that didn’t garner a sequel (though its title character starred in a handful of animated shorts). The movie was the second biggest release of 1988 and won numerous Oscars (while being nominated for even more), but its cultural footprint ended up being remarkably small. When’s the last time you heard somebody do a Roger Rabbit impression?

Roger Rabbit is one of the best films of its era, however, and it deserves to be remembered even more than it is, its unique blend of cartoony sensibility and more adult storytelling having anticipated so many of the blockbusters that followed. And if you remember the movie as primarily one about goofy cartoons and wacky slapstick, well, it has those elements, but it’s about something else, too.

See, along with Chinatown and L.A. Confidential, this is a movie about the secret history of Los Angeles.

Roger and Eddie are in a jam. Touchstone Pictures

It’s only natural that Los Angeles, home to the film and television industry, would pop up as the setting for many a film. And thanks to the city’s glossy exteriors and hidden corruptions, it’s also only natural that many of those stories would take the form of film noir — shadowy crime thrillers, often told from the point of view of detectives, which posit morally grey universes where survival often means making yourself almost as hard as the criminals who run everything.

I’ve long thought of Chinatown (1974), Roger Rabbit, and L.A. Confidential (1997) as a loose trilogy. All three contain elements of film noir, and all three are vintage Los Angeles stories, to be sure. But what unites them even beyond that is that all three tell incredibly skewed versions of true stories of how Los Angeles became the sprawling, congested megalopolis it is. No, a section of Los Angeles where cartoons lived wasn’t paved over to build the freeways — but many other things were.

Start with Chinatown, the iconic detective film starring Jack Nicholson and directed by Roman Polanski. (Polanski, who directed a few of the best movies ever made, including this one, also was convicted of raping a 13-year-old girl in 1977 and has been accused of several other cases of sexual assault and misconduct.) The movie’s airtight script by Robert Towne is perhaps the most traditional “noir” of this triple feature, from the hard-boiled detective (Nicholson as Jake Gittes) to the femme fatale (Faye Dunaway).

The film is also a genuinely compelling story about water rights, which is not something you can say every day. It depicts a very loose retelling of the efforts of William Mulholland to transport water from the Sierra Nevada mountain range south to Los Angeles, a city that would require substantial access to fresh water if it were to grow. (Mulholland’s shady practices happened in the 1900s, while Chinatown is set in the 1930s, so artistic license has been taken.)

The shifting of water toward the California coast, and especially toward Los Angeles, has become a constant source of strife in my state, and Chinatown’s most famous reveal (which I won’t spoil, but it involves a horrific sexual relationship) in some ways parallels the exploitation of the state’s once-abundant natural resources in order to sustain a growing population. In the world of Chinatown, everything is a resource to be consumed by unscrupulous men who don’t care about anyone but themselves.

Faye Dunaway and Jack Nicholson star in Chinatown. Corbis via Getty Images

Towne mounted a sequel in 1990, the Nicholson-directed The Two Jakes, but the movie’s lousy, perhaps because its depiction of late-’40s Los Angeles corruption had already been handled so much better, in even stranger fashion, in the 1947-set Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Indeed, the script for Roger was actually inspired by Chinatown in its attempts to warp and bend actual history to fit the framework of a blockbuster.

The chief difference between the two films — well, besides the cartoon characters — is in tone. Though Roger Rabbit depicts a very real event (the destruction of Los Angeles’s world-renowned streetcar line and the disruption of several historic neighborhoods, often populated by ethnic minorities, in the late 1940s to make way for the city’s infamous clogged freeway system), it also stars Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny, and the manic rabbit at the center, which means the film eventually tacks on a happy ending, where Toontown survives, the freeway presumably having to give up the ghost or find a way to go around it.

And yet the core of Roger Rabbit is a surprisingly accurate depiction of the ways that developers, politicians, and business executives worked with companies associated with the automobile industry to undermine and finally destroy the streetcar system. In that sense, the vaguely rosy Los Angeles of the film, where even the noir shadows are cast by a smiling cartoon sun, becomes a weird nostalgia trip for the filmmakers — a city that almost was.

Finally, there’s Curtis Hanson’s L.A. Confidential, in which the “secret history of Los Angeles” trilogy finally turns its eyes on Hollywood itself. If Los Angeles has always been, on some level, a company town where all of its millions of residents have some sort of connection to the entertainment industry, then it only stands to reason that Hollywood would be just as corrupt as the city’s water supply and transportation system.

Confidential delivers that in spades, with an entire entertainment industry system designed to distract from the real culprits and keep the whole Hollywood machine looking beautiful, the better to keep film fans from seeing the way it rots from the inside out.

L.A. Confidential gave a big break to numerous young stars, including Guy Pearce. Warner Brothers/Getty Images

Confidential is based on a novel by James Ellroy, himself the author of his own series of novels about the darker corners of Los Angeles (a series that includes L.A. Confidential), and it shares Ellroy’s obsession with the idea that the history we’ve been presented is a thick gauze that obscures what really happened. Stare at it long enough and you might start to see the truth; you also might lose it completely from the strain.

What’s most notable about L.A. Confidential is the way that it posits the media — which has one of its major bases of operation in Los Angeles — rewrites what really happened to create a narrative that’s more palatable to a mass audience, something that may have been market-tested in Los Angeles (where the police help Hollywood bigwigs craft stories less likely to rattle the status quo) but which is clearly spreading throughout the country by the year 1953, when Confidential is set.

Every city, of course, has its own secret histories, its own barely obscured dark enigmas. It’s just that not every city has a film industry based in it. Indeed, it’s sort of a wonder that there aren’t more hugely acclaimed film noirs about the shady dealings that led to the birth, growth, and hyper-expansion of the City of Angels.

If you sat down and watched Chinatown, Roger Rabbit, and L.A. Confidential in a row, you’d have a great night of watching three very different takes on the detective drama. But you’d also get a lesson in how unethical, immoral, and often illegal political power built the modern American city — specifically the one supposedly meant to celebrate dreams, not nightmares.

Original Source -> Water rights, freeways, and Hollywood gossip: the secret history of LA, in 3 detective movies

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes