Text

Tankar kring En man som sover av Georges Perec

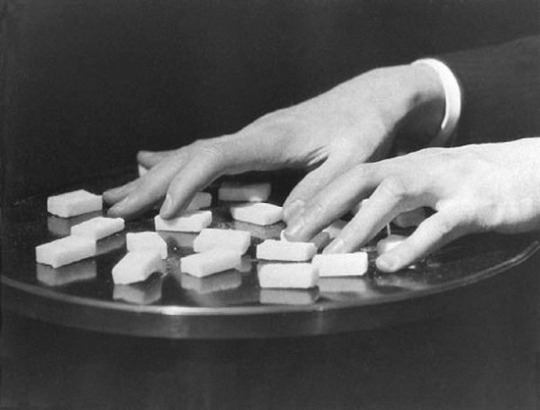

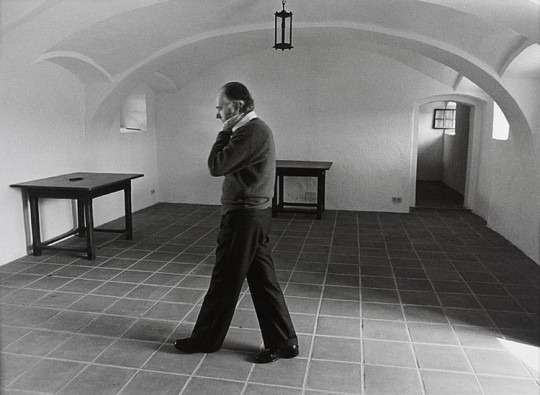

The Hands of Antonin Artaud av Man Ray, 1922

En man som sover är en annorlunda liten bok. Utan några riktiga karaktärer eller en utstakad handling sveps läsaren med i ett uppbrott från livet, där vi en dag plötsligt avsäger oss våra förpliktelser och väljer att röra oss genom världen sovandes. Perec har valt att på typiskt Oulipo-vis gå emot mer traditionella narrativ, och istället skrivit En man som sover i du-form.

Så överräcker Perec rollen som huvudperson till läsaren, och det blir jag som läsare som blir skriven, nästan instruerad. Det ger En man som sover känslan av något likt en manual: instruktioner i att gå genom livet sovandes, att leva i ”en välsignad parentes”. Den fulländade stillheten som eftersträvas kräver att banden till mycket av världen slits av, och den sovande måste arbeta fram en fullkomlig och allomfattande neutralitet. Preferenser, tyckanden och förväntningar behöver alla ges upp. I den sovande existensen behöver alla ting vara likvärdiga. Handlingar ska vara rena, klara och transparenta, utan bakomliggande innebörder. Handling som enbart handling, helt enkelt. Du, den sovande, bör inte gå tingen eller rummet till mötes i din önskan att definiera dem, och måste undvika att mäta dem med dina tankar eller påtvinga dem en mening. Istället kommer tingen visa sig för dig så som de är: platta, idel yta. Lev ditt liv i världen av ytor du skapar, inga budskap göms i verklighetens skrevor. Även nuet är ren yta. Historia och framtid är irrelevant; för stillheten du söker finns ingen annan tid än den nuvarande.

”Du härskar nu över världen i det fördolda, utom räckhåll för historien, du känner inte längre regnet falla, ser inte natten komma.” - ur En man som sover, Perec

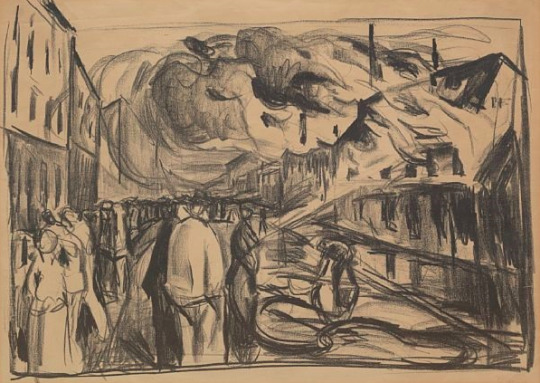

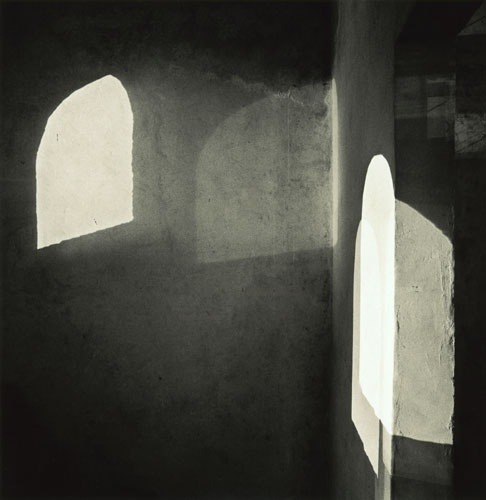

Scen ur Bernard Queysannes filmadaption Un Homme Qui Dort, 1974

På många sätt är sömnen lockande, rent av revolutionerande. Det finns en befrielse i hur hierarkier faller när vi avsäger oss mätande och vägande. Jag skulle gärna låta världen komma till mig istället ibland, låta den definiera sig själv utan mina ord, utan mitt våld, förgäves försöka tömma ett träd på innehåll. Tillfällen där tingen fäller sina påtvingade innebörder och träder fram i sin egentliga form har ett skimmer av något heligt, och med rollen som enbart betraktare lyfts världens vikt från ens axlar; det är tröttsamt att alltid vara tolken, navet. Men sömnen är också kyla, en täckmantel av medvetna begränsningar. Något döljer sig bakom den sovandes strävan efter likgiltighet. Jag har en svag punkt för ritualer och regler. De är sköna att hålla i när man är rädd för att gå vilse, när man inte litar på sig själv. Att finnas utan dem är skrämmande: vem vet vad som kan hända om man släpper sig själv fri, vill saker, önskar sig saker, förväntar sig saker? Bättre då att hålla sig sovande, även om det innebär att man ligger vaken hela nätterna.

Perecs syn för detaljer är närapå meditativ. Texten genomsprängs av listor och uppräkningar, mängder av information som antingen kan användas för att utvinna mening och innebörd ifrån, eller som ytor att vila ögon och sinne på, ett avstamp för stilla betraktande. Takten är behaglig och gör En man som sover fin att läsa om lite då och då. Modernistas fortsatta utökning av deras serie med Perec i svensk översättning känns hittills som ett mycket bra beslut!

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Fredrik Rönnbäck och släpptes 2016 av Modernista.

0 notes

Text

Tankar kring R.U.R. av Karel Čapek

detalj ur en av Stina Löfgrens illustrationer till boken

På Robotfabriken Rossum’s Universal Robots ältar direktörerna och en besökande kvinna de olika etiska frågor som Robotar och deras skapelse innebär, samtidigt som fabriken fortsätter att föda fram nya Robotar. De konstgjorda människorna har blivit omåttligt populära, snart finns de överallt, och en dag dyker en ny oro fram: den över mänsklighetens fortsatta överlevnad.

Robotarna som det nya normala ger en påtaglig effekt på samhället. Marknaden får tillgång till mängder med arbetskraft som aldrig behöver lunchpauser. Arbetare upptäcker att de plötsligt blivit utbytbara. Stater kan bygga militärtrupper där ingen samvetsvägrar. Religionen måste ta ställning till levande varelser som skapas utan guds finger i spelet. Den vetenskapliga utvecklingen har tagit ett språng som kulturen och samhället har svårt att hinna ikapp, och nu behöver allt omvärderas.

Nog känns det ganska udda att det är just det här verket som infört ordet ”robot” i vårt vokabulär; inte en tung filosofisk skrift eller ett månghundrasidigt litterärt mästerverk, utan en pjäs åt det tunnare hållet, science fiction-litteratur med lika delar komedi och tragedi. Trots enkelheten i den finns här mycket att smälta, så mycket att det är svårt att reda ut de olika idéerna från varandra såhär i efterhand. I R.U.R. får liksom alla komma till tals, här finns alla tänkbara tolkningar av de nya varelserna. Är de ett bevis för mänsklighetens övermod och därmed en skymf mot Gud? Eller är de grunden till en möjlighet att föra människan tillbaka till Adam och Evas tid, ett paradisiskt liv där ingen behöver sälja arbete för småmynt?

”Jag ville att människan skulle bli sin egen herre! Jag ville att hon skulle få leva för något mer än nästa brödkant! Jag ville se till att inte en levande själ skulle behöva gå och ställa sig vid någon annans maskin! Jag ville rätta till alla fel som vårt samhälle lider av! Jag avskyr att behöva se förödmjukelse och smärta överallt, jag hatar fattigdom!” - ur R.U.R., Čapek

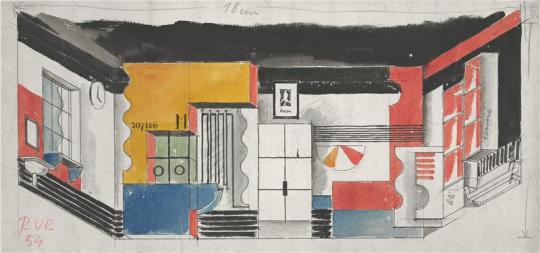

skiss för R.U.R. av Bedřich Feuerstein

Framsidan av Nilleditions utgåva kallar R.U.R. för en varning om vad som kan hända om vi skapar konstgjorda människor, men är det verkligen en varning? Čapek tar aldrig någon riktig ställning mot Robotarna, och vi får se bokens förlopp ur ögon som inte dömer, utan nyfiket observerar människornas olika reaktioner på framtiden de skapat sig. R.U.R. känns snarare som en fundering, en fråga.

Här kommer spoilers:

Inte ens bokens slut, där Robotarna utraderar mänskligheten, känns som en faktisk varning. Istället konfronteras vi med en undran om ifall Robotarna nu, genom sitt utövande av våld, faktiskt tagit sina första stapplande steg mot mänsklighet. Massakrer och folkmord är trots allt inte någon nyhet för människan; de har följt oss åt sedan vår tids begynnelse.

Här slutar spoilers.

Om R.U.R. är en varning så är det inte en om Robotar, utan om människor. Om hur vi ivrigt kan marschera mot avgrunden så länge vi får något för det, vare sig belöningen är materiell, ideologisk eller spirituell. Och ändå är vi som livsform på något sätt så välmenande, så svaga för alla de saker som gör oss till människor. R.U.R.s karaktärer är välmenande, vare sig de är drömmande idealister, effektivitetssträvande materialister, gudfruktiga arbetare eller defekta Robotar, och trots att de har vitt åtskilda uppfattningar blir ingen av dem presenterade som fel. Det är skönt på något sätt, att alla får ha goda intentioner. Čapek hade kunnat skriva en simpel moralpjäs, men jag tycker att R.U.R. klarar sig undan det.

”Jag reser frågan om det inte är möjligt att, i dagens sociala konflikter i världen, skåda en motsvarande kamp mellan två, tre, fem likvärdigt trovärdiga sanningar och jämbördigt välvilliga idealismer? Jag anser att så är fallet, och att detta är den moderna civilisationens mest dramatiska inslag, att en mänsklig sanning ställs mot en annan lika mänsklig sanning, ideal mot ideal, positiva värden mot icke mindre positiva värden, snarare än att kampen, som vi så ofta blir intalade, är mellan en nobel sanning och ond egennyttig lögn.” - ur The Meaning of R.U.R., Čapek, 1923

Knaben im Fluss av Josef Čapek, bror till Karel

Här går inte saker fel för att karaktärerna är onda eller har fel eller dåliga idéer. Samtidigt är alla skyldiga, alla har mer eller mindre motvilligt blod på sina händer. I sin essä The Meaning of R.U.R. kallade Čapek det som utspelar sig i boken för ”vetenskapens komedi”, hur mänskligheten tenderar att skapa sådant som vi snabbt förlorar kontrollen över. Hur massproduktion och profit springer om tankarna bakom dem. Samtidigt såg Čapek att det inte bara gick att sätta stopp för hjulen vi redan satt i rullning utan att döma stora delar av världen till misär. All vår filosofi, alla våra ideologier, innan vi vet ordet av så kapas de av världen vi skapat och rullar vidare utan oss. Vi hinner inte med oss själva.

Med R.U.R. lyckades Čapek skapa en ovanlig klassiker. Drama är ett annorlunda format för science fiction, men här funkar det bra och tillåter fokus att helt ligga på karaktärernas tankar och idéer. Som i så mycket sci-fi värd sitt namn så handlar trots allt R.U.R. om innebörden av mänsklighet, och presenterar oss med fler frågor än svar.

Nilleditions utgåva är snygg och inkluderar fina illustrationer av Stina Löfgren, men har flera fel i korrekturläsningen, och förordet av Lena Andersson känns underligt oengagerat. Något spår av namnet på översättaren finns ingenstans att hitta, och det enda förlaget säger när jag frågar är att det är en ”nybearbetning” av originaltexten. Min följdfråga om vem översättaren är får jag inget svar på.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska och släpptes 2016 av Nilleditions.

0 notes

Text

Att läsa Aednan ovan polcirkeln - tankar kring Aednan av Linnea Axelsson

Under det hellige berg av Tomas Colbengtson

Jag tvingas läsa Aednan på nära håll. Jag känner igen dammen och Porjus/Bårjås, återskapar platserna i minnet, och ännu mer känner jag igen människorna, tankarna. Ibland stannar jag upp och undrar hur den här boken vet så mycket om mig, om min familj, om oss. Likheten i så många av våra öden slår mig, hur där alltid finns samma fasta punkter att orientera sig från: markerna, språket och den skam och längtan det kopplats till, identiteten och att förlora den och hitta den, rasbiologin, ilskan och aktivismen. Gruvorna, dammarna och kraftverken som stora sår i kartans marker, i det samiska medvetandet. Vattenkraft. Girjasmålet. Vi har liksom alla fått samma kartor att läsa världen med. Jag läser Aednan resandes, på väg bort från lulesamisk mark, på väg hem och hemifrån samtidigt. Jag blir annorlunda där uppe, säkrare, stadigare. I Stockholm är det svårare, jag känner hur jag vinglar när jag vill skriva om ett ”vi”. Nu gör jag det ändå.

”Det var i ett klassrum

i Malmberget

-

Jag hörde läraren

än en gång berätta

om folkhemmet

och Sveriges

berömda solidaritet

-

Medan mamma

och pappa fick

klättra i backarna

Försöka gissa hur

högt upp älven

skulle stiga

innan de började

riva huset”

- Ur Aednan, Linnea Axelsson

Aednan, det äldre nordsamiska ordet för marken som i mitt rättstavningsprogram följs åt av ett argt rött streck, är namnet på Linnea Axelssons nya diktepos, två släktsagor som sträcker sig över hundra år, från tvångsförflyttningen av Karesuandosamer till Girjas samebys stämning av svenska staten. Ordet ”diktepos” för lätt med sig förväntningar om tyngd, något ogenomträngligt som bäst överlåtes till professorer i antika språk, men Aednan är välkomnande och rytmen går fint att komma in i.

Silverfjället av Tomas Colbengtson

Det finns en väldigt drömsk kvalitet i Aednan som är tydlig i bokens början, någonting uråldrigt och samtidigt så nära, men även i nutidsdelarnas vardagliga gång ekar spåren av det, som ett till hälften bortträngt minne som nu mest bara känns i kroppen. Karaktärer och minnesbilder rör sig in och ut ur tidslinjen, och här är det tydligt: nutiden bär alltid gårdagen med sig, ingenting står utan sin historia. Det är ett viktigt drag, för det är genom kontext och historia som vi kan se det inneboende våldet i händelser som annars får slippa undan. Det är genom historiens ögon som en nedbränd kåta blir mer än bara en hög med aska.

”Ni nordiska barn

som går fram så lätt

Som vore ni

helt utan makt

utan förflutet

-

De som gått före er

har visst glömt

att packa er ryggsäck”

- Ur Aednan av Linnea Axelsson

Jag tror att Aednan gav mig ännu en bit kraft, gav mig orken att veckla ut den där kartan, dra med fingret längs med floderna, försöka hitta punkten där jag är. Det finns en värme i att veta att vi är många som vandrat samma leder. Samlats på samma punkt. En del av mig undrar vart fan jag ska ta vägen nu. En annan minns att vi är många, och att vi leder varandra när föret blir svårt.

Utgåvan jag läste släpptes 2018 av Albert Bonniers förlag.

0 notes

Text

Recension av Dzjan av Andrej Platonov

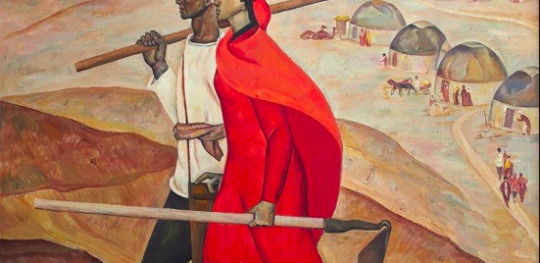

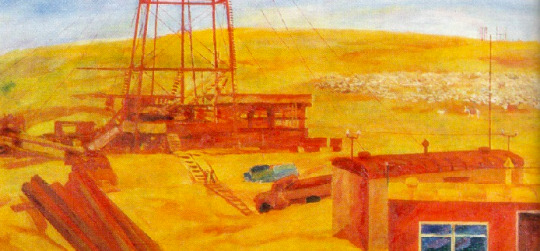

detalj ur The first av Durdy Bayramov, 1968

Att sprida lycka är inget enkelt jobb, speciellt inte när alla alltid är så olyckliga. Men när det är framtiden själv som är på väg är ingen uppgift för svår. Det unga Sovjet sträcker på sig över landmassorna; här ska lycka och utopi införas. Även den turkmeniska öknen ska frälsas, och dit skickas den idealistiske Tjagatajev, född i samma öknar men tidigt överlämnad till statens fostran, för att nu liksom en biblisk herde samla ihop sin vilsna flock. I Tjagatajev har vi den perfekte sovjetiske hjälten: alltid lycklig och redo att sprida sin lycka till andra, ärlig, ansvarstagande, nyutexaminerad i Moskva. Rätt sorts man för att bygga socialismen åt det fattiga ökenfolket Dzjan.

Tjagatajev är oskyldig som ett barn, som en ny människa, och det är väl också den nya människan som är hans roll. Han får representera ett nytt ideal i en ny stat på jakt efter förebilder. Med sig bär han en i det närmaste Jesus-lik kärlek, tålmodig, aldrig svartsjuk, grundad i en ömhet till mänskligheten snarare än ett individualistiskt begär. En sorts socialistisk ideal-kärlek, långt bort från idéer om ägande och exklusivitet, och för Tjagatajev flyter den samman till en stor medkänsla för samhällets svaga. Samtidigt besitter han en fullkomlig oförmåga att förstå andras känslor kring olycka och sorg. Varför är inte alla bara lyckliga? Världen rusar framåt i en fruktansvärd fart, utopin står för dörren, och här går folk runt och sörjer, lider, gråter precis som vanligt. I Tjagatajevs ögon blir det ofattbart, för honom är svält, ensamhet och förtvivlan alla övergående reliker från en döende värld, inget att dröja vid.

detalj ur New Birth av Izzat Klychev, 1972

Tjagatajevs tapperhet och idealism är ärlig men naiv, och från Platonovs håll känns den något påklistrad. Det i sig ger ändå Dzjan en fascinerande kluvenhet. Platonov var själv kommunist, men förhöll sig skeptisk till Stalins förda politik, och det är svårt att avgöra om mycket av boken är försiktig kritik eller en uppslukande längtan till att helt utan tvivel kunna tro på Sovjets framtid. Dzjan är därför intressant som en inblick i det sovjetiska författarpsyket, men är inte alltid så fängslande i sig. Svårigheterna Tjagatajev får gå igenom flyter snabbt in i varandra, och som läsare vänjer man sig vid plågorna han utstår. Personporträtten bortom honom är alla ganska platta och ensidiga, andra karaktärer finns främst till för att kunna räddas av historiens hjälte. Dramatiska skeenden känns underligt dämpade.

Ändå finns en tråd genom texten som fångar mitt intresse: i Dzjans värld finns en mycket speciell relation mellan människan och annat liv, ett ömsesidigt bekräftande som pågår mellan person och växt, smådjur eller föremål. Tjagatajev söker konstant kontakt med landskapet runt omkring sig. Kanske är det en överlevnadstaktik från barndomens ofrivilliga exil, ett sätt att säkerställa sin existens. Hos Platonov blir inte en plats främmande när du glömt bort den, utan när själva platsen inte längre minns dig. Här finns en tanke kring en själ hos allt i världen, och inte nödvändigtvis en religiös sådan utan snarare existensen själv, något inkännande och igenkännande och stilla. Det är handlingen att existera i sig som är helig, och den till synes tomma öknen sjuder i själva verket av närvaro och värdighet.

”i ögonen på en sköldpadda fanns det en tankfullhet och i en slånbärsbuske fanns det väldoft; vilket innebar att det fanns en stor inre värdighet i deras existens - en värdighet som inte behövde kompletteras av en mänsklig själ. Kanske behövde de lite hjälp från Tjagatajevs sida, men överlägsenhet, nedlåtenhet eller medömkan behövde de inte…” - s. 155

Andrej Platonov (1899 - 1951)

Här kommer spoilers:

Det lyckliga slutet är djupt tillfredsställande. Det är också minst lika absurt, omöjligt att tro på. Och visst känns det lite som att Platonov inte är fullkomligt övertygad själv? Inte så att det känns ironiskt, utan snarare som ett desperat rop på hopp, en stilla bön inför Stalins byst. Låt lidandet sluta. Låt alla folk leva i lycka och fred. En tidigare version av Dzjan är väsentligt kortare, över 30 sidor. Där är slutet istället ambivalent: folket har vunnit ytterligare tid tack vare Tjagatajevs insats, men ger sig alla av åt olika håll på stäppen för att möta sina egna öden. Resultatet blir närapå en helt annan bok. Istället för den sovjetiska drömmen får vi en historia om hur man kan sträcka ut en hand till sina medmänniskor, och om hur dessa inte har någon som helst skyldighet att greppa den. Det blir en bok om den mänskliga själen och dess frihet att välja sitt liv, att vara lycklig eller olycklig, frodas eller lida. Om det viktiga i att förse alla med grundläggande möjligheter och trygghet, och allas rätt att göra med det vad de vill, oavsett vad vi anser om deras val.

Enligt översättaren Kajsa Öberg Lindsten är det nyare, tillagda slutet del i ett ”försök att passa in i ett sovjetiskt litterärt projekt” och att ”skapa positiva skildringar av Centralasiens sovjetisering”. Av allt att döma var Platonovs försök ett misslyckat sådant. Dzjan stoppades av myndigheterna, och Platonov fick aldrig se sin bok utgiven; en första publicering skedde inte förrän efter hans död, och i Ryssland kom den ocensurerade versionen först 40 år senare.

Här slutar spoilers.

I Dzjan finns inte mycket plats för språklekar eller experimenterande, istället verkar språket jobba på ett visuellt plan, menat att fånga och framkalla olika flyktiga känslotillstånd. Textens språkliga grepp påminner mig lite om vissa målningar i naiv primitivist-stil. Ytan är detaljerad, men den övergripande stilen är enkel och öppen. Någon uppenbarelse blir inte Dzjan till slut, men det är ändå en välskriven bok som är värd att läsa för den som intresserar sig för Sovjet och dess författare och tänkare. Själv är jag nu nyfiken på Platonovs större verk Grundgropen som säkerligen kommer hamna här i arkiven så småningom.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Kajsa Öberg Lindsten och släpptes 2009 av Ersatz. Recensionen ligger även ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

0 notes

Text

Recension av Heldenplatz av Thomas Bernhard

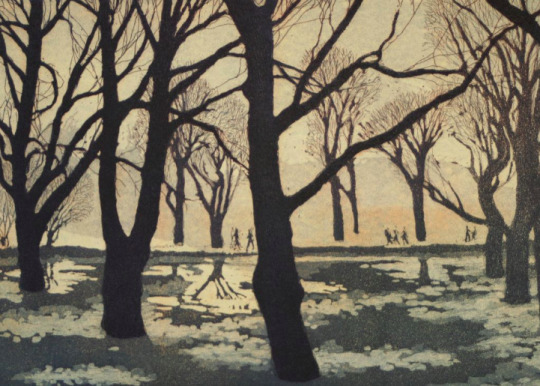

Great Park av Heta Kananen, 2007

I Bernhards Heldenplatz försöker ett antal familjemedlemmar och bekanta navigera ett självmord, men också en stad och ett land som förrått dem alla. Pjäsen hade premiär på 50-årsdagen för Nazitysklands annektering av Österrike (pjäsens namn syftar på torget i Wien där Hitler välkomnades av jublande folkmassor 1938), och orsakade stor skandal i hemlandet. ”Ut med skurken!” ska den österrikiska högerpolitikern Jörg Haider ha uppmanat, och nog räckte det för att göra mig intresserad.

När vi kommer in i pjäsen har den judiske professor Schuster tagit livet av sig genom att kasta sig ut från fönstret som vetter över Heldenplatz, själva symbolen för Österrikes delaktighet i kriget och förintelsen. Schusters närmaste samlas för en enkel begravning, och får så gott det går vädra sina känslor kring det skedda. Det blir en studie i tyst, bittert raseri och likgiltighet, ett möte mellan dem som inte kan blunda och dem som inte orkar se. Att protestera hela livet lämnar ingen plats för sinnesro, men kan man verkligen gå vidare och leva bland människor som ett halvt liv tidigare villigt kastat en åt vargarna? Påfrestningen av att inte känna sig välkommen i sitt eget hem sliter på karaktärerna. ”Vi trodde alla att vi hade ett fosterland”, säger en av dem, ”men vi har inget”.

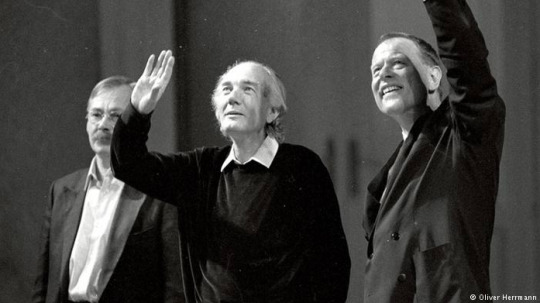

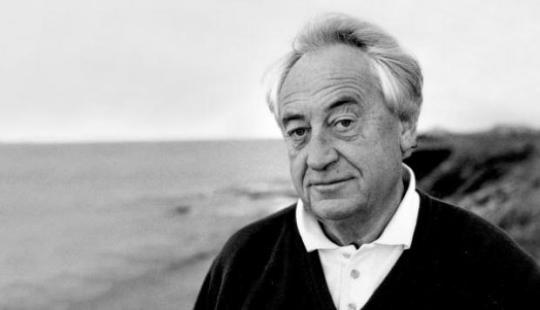

Thomas Bernhard (mitten) och Claus Peymann (höger) som satte upp Heldenplatz på Burgtheater Wien

Som ofta med Bernhard spelar platsen sin egen roll här. Platsens påverkan på individen är enorm, och ett liv kan i mångt och mycket definieras med var det levdes; en karaktärs födelseort är minst lika viktig och inflytelserik som dess föräldrar. Befinner man sig på fel punkt i världen går man snabbt under, och inte många platser är så fel i Bernhards sinnevärld som Wien. Så hur formas man av att leva på en så historiskt ödesmättad plats, när själva rummet bär på så tungt bagage? I Heldenplatz flyr vissa staden, andra flyr livet, åter andra försöker leva med skriken.

”i Oxford kommer hon inte längre att få några anfall, sade professorn, det finns ingen Heldenplatz i Oxford, Hitler var aldrig i Oxford, det finns inga wienare i Oxford, massorna skriker inte i Oxford.”

Tyvärr är Heldenplatz’ historiska och politiska kontext nog mer intressant än pjäsen i sig själv. Det finns ofta ingen vidare skillnad mellan de olika rösterna vi får lyssna på, och visst blir det ändå lite väl självmedvetet med alla referenserna till teaterkonsten och dess förfall. Här finns mycket intressant att gräva i, men jag ser inte riktigt någon anledning till att det är som pjäs Heldenplatz behövs, och inte som novell. Heldenplatz är ingen favorit, men den är läsvärd ändå, dess plats i Europas litterära och dramatiska historia är både intressant och viktig, och så är det ju trots allt Bernhard.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Jan Erik Bornlid och släpptes 2011 av Bokförlaget Tranan. Recensionen ligger även ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

0 notes

Text

Det finns verkligen inte mycket i bokväg som slår Ellerströms serie med nyöversatt grekisk dramatik. Prometheus: inte lika drabbande och superdramatisk som Kung Oidipus, men nog är den bra!

0 notes

Text

Recension av Azorno av Inger Christensen

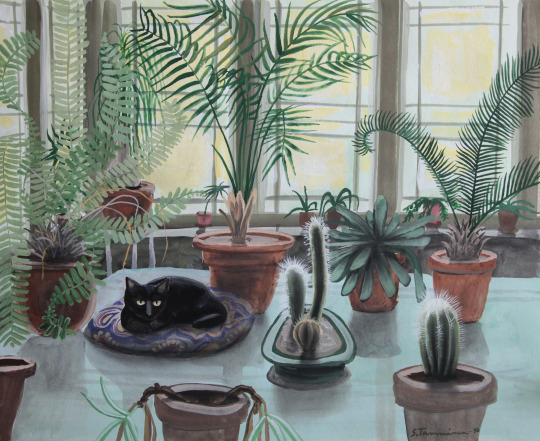

On the Veranda av Seppo Tamminen, 2009

”Det är så grönt att det svartnar” - Azorno

De är alla fångade i varandras ögon, de fem kvinnorna i Azorno. En efter en tar de genom bokens gång kontroll över dess form, krossar den förras vittnesmål mellan fingrarna, bygger upp historien på nytt. Alla är de kopplade till författaren Sampel och dennes karaktär Azorno som dyker upp tidvis i Köpenhamn, i Rom, i de Schweiziska bergen. ”Ett olösligt samband, infiltrationer rakt igenom” skriver en av kvinnorna om Sampel/Azorno, och här experimenteras det ordentligt med författaren, hens roll i vad som är sanning, och förhållandet mellan den som skriver och den som blir skriven om. På många sätt är det en roman om skrivandet självt, dess rytm och rörelser. Vi får erfara hur en helhet byggs upp av en mångfald intryck, hur intrycken vrider sig, sätts i nya sammanhang, och får nya innebörder.

På så sätt ger Christensen läsaren delarna till ett pussel, bit efter bit, men det är som att de alla kan haka i varandra i ett oändligt antal kombinationer. Att läsa Azorno är att omslutas av ett virrvarr av rosor, solrum, brev och fontäner. Allt återföds gång på gång. Sinnebilderna duggar tätt genom boken, upprepas och mångfaldigas tills läsaren sitter i ett spöregn. Bitarna vi får till hands läggs samman och plockas isär för att sedan sättas ihop igen, varje gång i nya konstellationer. Är någon av de resulterande bilderna det faktiska, sanna pusslet, eller är de det allihopa?

Inger Christensen

Azorno är i högsta grad en poets roman, för först och främst var Christensen ändå poet (en av det moderna Europas viktigaste). Texten är som dränkt i bitter växtsaft. Överallt i boken konfronteras vi med en obönhörlig växtlighet, och det går en tråd av fertilitet genom alltihopa, Christensen verkar besitta en så intim kännedom och intuition kring födande-levande-döende. Rankor skjuter ut ur moderväxten, tyngs av sina blommor, vissnande växter löses upp i stoft, pollen fyller luften. Det är en grön labyrint som man måste gå igenom ensam, men som man vet att hundratals passerat igenom före en själv, kvinnor med tankarna fulla av andra kvinnor. Christensens karaktärer lånar varandras namn och kroppar, bygger sina narrativ genom andra för att bryta stumheten de bär på och som ett sätt att motarbeta språkets och namnens förmåga att stänga in och begränsa.

Här i labyrinten finns ett lugn, en form av dämpad ro där allt ses som genom ett gröntonat kalejdoskop. Ibland anas en bitterhet i lugnet, en vetskap om att kärnan i den består av något ensamt, något längtande. En väntan kanske. Azorno lyckas verkligen fånga en atmosfär av ensamhet väldigt bra, den nästan genomsyras av ensamhet trots att vi följer så många(?) karaktärer, och jag skulle nog säga att den också ska läsas just så, ensam, helst i en trädgård. Själv kommer jag fortsätta ta mig igenom Christensens författarskap, som att döma av Azorno har varit ett mycket speciellt och värdefullt sådant.

Recensionen är skriven en majdag vid ett rangligt cafébord under ett parasoll på en grön bakgård. Ingen fontän. Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Marie Silkeberg och släpptes 2011 av Modernista. Recensionen ligger även ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

0 notes

Text

Recension av Petersburg av Andrej Belyj

The Revolution by Marc Chagall, 1937

Hur känns det när ett samhälle spricker, när det sönderdelas till sina minsta atomer för att sedan återigen byggas upp i ny skepnad? Petersburg utspelar sig kring precis ett sådant uppsprickande där allt liksom hänger i luften, där varje steg hotar att förråda en. Ingenting är längre fast.

Bland St. Petersburgs sjudande prospekt möter vi Apollon Apollonovitj Ableuchov, högt uppsatt ämbetsman; här finns även hans son Nikolaj Apollonovitj, ung intellektuell romantiker som umgås bland revolutionärerna, och så den Ogripbare, en av dessa unga revolutionärer. Under en period på några dagar kommer de oroliga svängningarna som länge rört sig genom staden och långsamt fortplantat sig in i alla deras sinnen att till slut klyva berggrunden däri. En bomb i en sardinburk kommer byta händer, en röd maskeradkappa kommer dyka upp på gatorna, våra karaktärer kommer alla att plågas av sina personliga hjärnspöken. Känslor, sinnebilder, slutsatser, aningar; i Petersburg är tankarna nästan som en sjukdom, de tar över den tänkandes psyke, sprider sig, till slut är de överallt. Även berättaren är förföljd, i hans fall av staden själv, av broarna, gatorna, vattnet.

St. Petersburg blir under den här tiden i historien ett sorts centrum, en punkt i universum där all massa samlar sig, staden blir så tung och mättad. Här hänger revolutionen som en dimma över kajen, ibland som ett hot, ibland som ett löfte, men alltid tveklöst ofrånkomlig, där är den, ständigt på väg mot torgen, in i salarna, in i den ryska själen. Det är som att historien till slut bara hinner ifatt. En väldig rörelse skymtar strax under den flortunna ytan, bronsstatyn vakar.

Brann by Edvard Munch, 1920

Livet i Petersburg bär på en ständig dualitet. Den äldre Ableuchov har levt sitt liv i ordningens Petersburg, i städade salonger bland rätlinjiga prospekt. Han äcklas av proletariatets kaos, dess ”mångtusenhövdade människosvärm”, istället dras han till det linjära, enkelheten, till och med tiden ser han som en linje mellan två punkter. Men så kan Peter den Store plötsligt skälva, den tvåhövdade stadens andra ansikte vänds till. Kaosets, skuggornas Petersburg blossar upp och slår ut efter en tid av oro, röda kappor och ändlöshet. En ny, cirkulär tid bryter sig igenom stadens raka linjer, den Ableuchovska tiden krossas, mals till damm. Historien är oundviklig, nuet likaså, framåt breder rymden ut sig.

Förhållandet mellan far och son Ableuchov, det gamla och det nya, är smärtsamt. De båda bär på en blandning av ömhet, äckel, fasa, medkänsla och skam för varandra, och allt gör ont, varje interaktion dem emellan är som att röra vid ett bultande blåmärke som de inte kan dra sig till minnes hur de fått. Till slut visar allt som förankrat våra karaktärer i vilka de är och världen de lever i tecken på upplösningstillstånd. ”Det finns varken paragrafer eller bestämmelser längre!” utropar Apollon Apollonovitjs intryck av sin son, och det stämmer allt mer, kaoset närmar sig, oron och den sköra relationen mellan far och son rusar mot sin spets, och även revolutionären, den Ogripbare själv, är på väg mot vad som närmast verkar vara ett hål i världen, inget är som det ska vara, verkligheten har vänt ett absurt ansikte till. Till sist uppenbarar sig bomben, och det är den som hotar att bli medlet som kan få intet att sippra ut. Bomben ruvar på det slutliga.

Belyjs text är vacker, trots att den inte alltid nödvändigtvis beskriver vackra saker. Hans stil har blivit både råare och jämnare sedan Silverduvan, försöken till romantik har fått stryka på foten. Kvar finns den musikaliska kvaliteten i texten, fylld med upprepningar och pauser. Det är en vacker bok att läsa högt, och jag har ett antal gånger plockat upp boken igen bara för att läsa några enstaka rader som flyter särskilt fascinerande. Här gäller en annan rytm, och nog är den närapå en femma, den här boken. Visst finns det ställen som skorrar och drar, men Petersburg har helt klart bara påbörjat en mycket lång tjänst hos mig.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Kjell Johansson och släpptes 2007 av Murbräckan. Recensionen ligger sedan 2018 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recension av Silverduvan av Andrej Belyj

Fairy Tale by Martiros Sarian, 1971

There is something at the horizon, closing in on the vast Russian fields. Russia is changing. Revolution is around the corner, whispers are heard of class, socialists, riots. Bely drops the reader into the slowly intensifying turmoil that in many ways defined Russia in the early 1900s. Here, people are offering resistance any way they can; demanding a fair wage or joining the flagellation cults are both ways of defying the old and safe structures. Everything in The Silver Dove is happening at the edge of an abyss, one that lies in the near future of both our main character Daryalsky and of Russia herself.

Daryalsky is an educated Muscovite, a poet, who like many others at this time leaves the metropolis for the rural parts of the country. Here, he has a fiancée, a girl from a noble family that could easily pass in any romantic literature from the century before: young, kind and innocent to a fault, blue-eyed and rosy-cheeked. And yet, there is something about this time, about this point of history, that makes her and her family and their manors and gardens impossible. Instead, Daryalsky becomes entranced by a simple, pockmarked peasant woman, as well as the secretive cult she belongs to, the one that has named her as their own Virgin Mary.

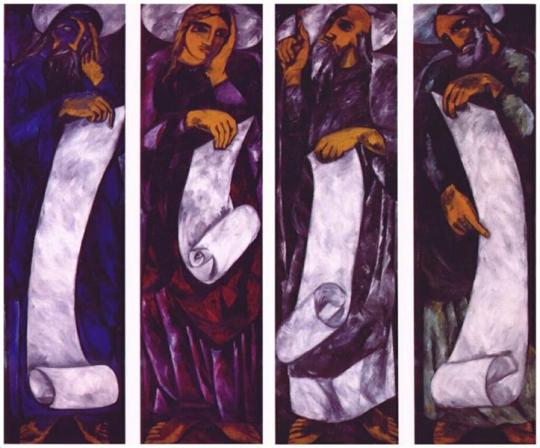

The Evangelists (in four parts) by Natalia Goncharova, 1911

The prose is difficult to pin down. At first it’s heavy, gaudy almost. Distinctly purple with odd repetitions, it made me worry that The Silver Dove would be a chore to get through. But what at first seemed amateurish and outdated soon gained some sort of rhythm, and for some chapters, the text seemed to be living and moving. I say for some, because being Bely’s first novel, this book can be pretty uneven at times. There are chapters that seem more like awkward attempts at a more traditionally romantic style, and the results are plodding and dull. But, overall, The Silver Dove is intriguing rather than heavy thanks to a playfulness and willingness to experiment that shines through, and I’m happy it does, because the better parts of the book are extremely intriguing, and a testament to Bely’s skill at building an atmosphere. The heat is suffocating, flies are abundant, and nature here is very much alive, almost to the point of consciousness. This is where the ornateness of his prose and all of that curious repetition falls into place, and something remarkable happens: all senses leave their assigned places and are taken in as if at once, everything becomes saturated with perception, the text turns as heavy as water, pooling into a complete cacophony of impressions. There is something surrealist about Bely’s use of nature; it is a constant witness and spectator, the Russian forests and plains are ever present in the world of The Silver Dove. Everything whimpers and snakes and whispers.

This way of putting feelings and senses over realism earned Bely a ban on his books in Soviet Russia, even though he himself was sympathetic to the communist cause. Maybe some of the authorities’ discomfort also stemmed from the fact that The Silver Dove isn’t a glorifying manifesto. Sure, the struggles of its time are all here; the struggle between city and countryside, intellect and hard work, civilization and the plains; the tug of war between East and West causes the entire weave of the book to shiver and quake - but there seemingly are no clear winners. A dangerous concept to a power who preferred literature to be useful and serve their purpose. They might’ve also disagreed with the book’s heavy dose of occultism (the parts featuring it might be its best - Bely is remarkably good at depicting the intense feel of ongoing, ecstatic rapture).

Unfortunately, Bely often disappears into side tracks long enough to interrupt the almost trance-like atmosphere that he’s built. But the amazing, breathless stretches that we do get are enough to make this a good book, and one worth reading.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Kjell Johansson och släpptes 2001 av Murbräckan. Recensionen ligger sedan 2017 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

#the silver dove#silverduvan#andrei bely#andrej belyj#book review#bokrecension#literature#litteratur

0 notes

Text

Recension av Följande historia av Cees Nooteboom

Orange, Black and White Composition by William Scott, 1953

Usually, reading feels to me like entering into a conversation with the author. Sometimes the conversation turns out better than the book itself; the ideas in the book turn into a kind of sounding board, and I end up appreciating the time spent with the author, their language, and their various passions. It’s why I like reading Bernhard or Cortázar even if I don’t necessarily always like the particular book in front of me, and I miss their company after I’m done. In a similar way, while I found The Following Story to be an ok book, I really didn’t feel like staying in this kind of exchange with Nooteboom.

The Following Story contains a lot of things that would normally make me a very happy reader. Classical languages teacher Mussert wakes up one morning to find time and space out of joint: the bed he’s woken up in is not the one where he went to bed the night before. A lot of greek mythology is involved, as is a theme of disintegration and metamorphosis that I really liked. And still, most of it simply didn’t grab me, neither the spirit of it nor the style.

Cees Nooteboom

At first I thought I might just be satiated with this kind of character: main character Mussert is an intellectual but incompetent in most other areas of life, badly adjusted to the modern world, likes his books more than he likes people, towering over hoi polloi in intellect and insight. You know the kind. It’s a common character type in these kinds of books, but written the right way it can be mercilessly clear-sighted, as well as a lot of fun. A character like this needs to be played with and challenged, and the author needs to expose their character in all its inanity and complacency, to throw the windows open with a bang, letting fresh air in and confronting the reader (or maybe even the character, should they not be too stubborn) with real life, a contrast to the ego they’ve created. The self-loathing turned self-absorption becomes interesting because we get to explore it. Instead, Mussert’s naivety and alienation feels boring and cliché. The sarcasm Nooteboom uses seems fake, as if it’s there to protect rather than reveal, and the feeling of self-satisfaction oozing from the text didn’t come just from Mussert, but from somewhere behind the scenes as well. Nooteboom seemed to be somewhere out there patting his character on the back.

The style and writing itself unfortunately did next to nothing for me as well. It simply didn’t feel sincere, and to me that is a deal-breaker. Nooteboom just couldn’t convince me with The Following Story, and though there are many interesting themes and some nice bits, it ultimately felt kind of empty.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Ingrid Wikén Bonde och släpptes 2014 av Modernista. Recensionen ligger sedan 2017 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

#the following story#het volgende verhaal#cees nooteboom#book review#bokrecension#literature#litteratur

0 notes

Text

Recension av Korrigering av Thomas Bernhard

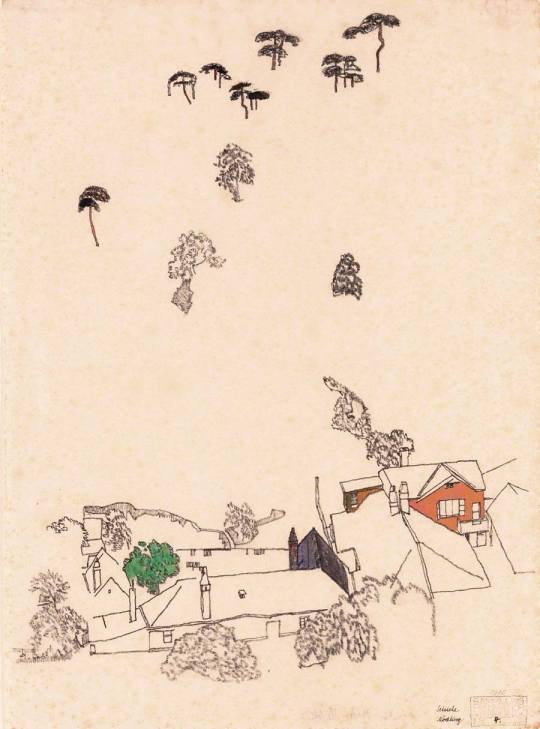

Houses and Pines by Egon Schiele, 1915

The sound of woodworms permeates the rooms of Altensam, the Aurach echoes between the walls of the houses. There is a sense of finality to Bernhard’s writing. Corrections is a dense book, with passages like walls. Most of it consists of just one long paragraph, feeling somewhat like a slab of rock. Impenetrable, with the pace almost palpably weighing on the reader, urging you to get going. Austria is cold and damp, the Aurach river deafening.

This is where our narrator has come to sort out the papers left behind by his dead friend Roithamer. He’s not new to this place; they both grew up around these areas of the country, and it’s where Roithamer fulfilled his obsessive plan of creating a building in the shape of a cone for his sister to live in. When we enter the picture, the cone is already finished, as is Roithamer, and the unnamed narrator is picking up the pieces of what is left behind.

Suicide is very prevalent, if not ever-present, in Corrections, and it’s something nearly inevitable to many of the inhabitants of Bernhard’s Austria. There, everybody carries their own end with them from the very beginning, just like they all carry the woods and mountains around which they grew up, the War, and Austria itself. The people in Corrections belong to and often even directly correspond to places. A mother from Eferding becomes ”that Eferding woman”, a brother from Altensam is ”Altensam through and through”. Most of Bernhard’s austrians belong to their places of birth and their hometowns like they do their mother’s womb, but there are other, more unfortunate ones, who never manage to agree with the places that ought to be their own. They search for other spaces than those familiar and scorned by them, and might move away to England, or build a house in the middle of a mountain pass, or maybe build a house shaped like a cone.

Geschälte Stämme by Albert Renger-Patzsch, ca 1957

I’ve been catching myself wanting to talk to people about the cone a lot. It is at once serene and sinister, a monument to both love and loneliness. There it stands, in the middle of the woods, built so that it can’t be seen until it is right in front of you, constructed to completely invoke Roithamer’s sister and her character. She must be happy here, Roithamer feels, and the cone quickly turns from an interesting idea into something absolutely horrifying. It’s too intense, as if you’d venture too deep into yourself in there, and get stuck in your own mind inside the cone. He wants this cone to be an absolute reflection of his sister’s very essence, and stories about meeting your double are horror stories. The cone becomes an intrusion, too close and too complete, something that desecrates all limits of the private and individuality. This is very much the quality I love about Corrections; the uneasy, creeping, confined. I want more of it. It works so well with Bernhard’s woods and mountains, a type of nature that somehow destroys and corrupts those that lives in it’s midst, robbing them of anything close to purity and innocence. In Bernhard/Roithamer’s world, the place and the character must be tightly intertwined, and the place easily wins the upper hand. Roithamer’s cone is in many ways an attempt to reverse this connection and to tame the place, making it conform to the person. Of course, the question is if that is at all possible. If we’re not all inescapably tied to our places.

Thomas Bernhard by Barbara Klemm, 1981

Bernhard really excels at several things. His words, the atmosphere, the repetition and the precision are all unique, and he is a master at making things so exact that they turn completely unintelligible. Sometimes, though, I feel like he loses his focus, forgets what he’s doing, and gets stuck in a way that detracts from the pacing. It easily becomes a bit too much, a couple of steps too many through the woods where every tree eventually looks the same. When that happens I tire of Bernhard a little and long for when he’ll get back on even keel again, impatiently plodding through the pages. Those are also the parts that won’t really let me give Corrections a higher rating; no matter how much I loved many elements of this book and dreaded and longed for the cone I’d get interrupted by long parts where the author seems to have gotten lost. The narrator’s neurotic repetition and need of exactness eventually start feeling like the author’s, and so finally what seemed like the narrator’s flaws (which were fascinating when they were his) instead became those of Bernhard himself (which becomes decidedly less interesting, and a lot more frustrating). If I’d only rate Corrections on the first half of the book, it would’ve been close to five stars. The other half turns away, becomes unfocused, and somehow gets stuck in its own disarray, just like Frost did earlier. (The translator’s note in the end of my Swedish edition sheds some light on some of the book’s problems: it explains that the original seemed to have been hurried by Bernhard, and written while focusing on some of his other books. How cohesive Corrections appears to the reader is very dependent upon the choices of the translators and publishing houses; the one that I’ve read has made the choice to leave what translator Jan Erik Bornlid says are sentences that lose their initial reasoning, as well as sentences that completely contradict themselves or earlier ones. It does however follow the original publisher’s suggestion to correct sentences that were left unfinished by Bernhard.)

But no matter how demanding Bernhard feels at times and how frustrated it makes me, I’ll keep reading more by him. I can’t tear away from his words, his places, the loneliness and the cold. It’s the claustrophobia that pulls me back, and the cone that looms among the trees.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Jan Erik Bornlid och släpptes 2014 av Bokförlaget Tranan. Recensionen ligger sedan 2017 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recension av Nadja av André Breton

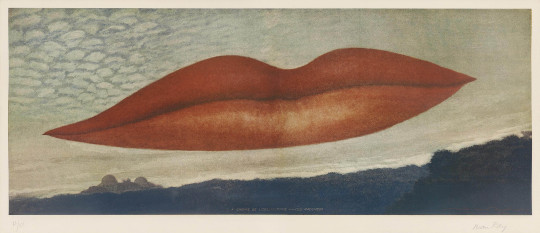

Les Amoureux by Man Ray, 1967

”The surrealists were not good with women. That is why, although I thought they were wonderful, I had to give them up in the end. They were, with a few patronised exceptions, all men and they told me that I was the source of all mystery, beauty, and otherness, because I was a woman - and I knew that was not true. I knew I wanted my fair share of the imagination too. Not an excessive amount, mind; I wasn’t greedy. Just an equal share in the right to vision. When I realised that surrealist art did not recognise I had my own rights to liberty and love and vision as an autonomous being, not as a projected image, I got bored with it and wandered away.”

That quote is by British writer Angela Carter, and it neatly sums up a large part of my criticism of Nadja. I do love the surrealists, but their ways of writing female characters are so incredibly tiresome, and I’m afraid my interest in surrealism will one day make me read one too many of these characters and make me roll my eyes hard enough to hurt myself. Nadja was a close call.

The Nadja of the title is of course special. She’s fragile, not as jaded as the suffering male narrator (Breton himself), too innocent to see the world as the cynical place that it is. She doesn’t know what she’s doing in Paris, and is usually seen just drifting around the streets. If you feel like you’ve heard this before, it’s probably because you have. Literature is flooded with these characters, the mysterious, always startlingly beautiful women who engage in complicated relationships with the brooding male protagonists.

Distortion #49, Paris by André Kertész, 1933

Now, there is a lot about Nadja that could make her interesting. She possesses an enormous creativity that feeds into her paranoia, and she is alienated from society in several ways; poor, alone, mentally ill, but I really would’ve preferred hearing about those experiences from her, and not just through the gaze of Breton. Instead of getting to know these sides, all of this makes her into some magical and free being in his eyes. Her reality simply doesn’t matter to him, unless greatly romanticised into something he can easily stomach. To him, she seems to only matter as a symbol and a muse, and in perhaps the ultimate description of the involuntary-muse-of-literary-men he writes: ”for she is so pure, so free of any earthly tie, and cares so little, but so marvelously for life.”

This perceived purity, or rather the innocence that comes with it, seems to be a major part of Breton’s dreams of the surreal qualities of a truly liberated consciousness, of art and life without boundaries. This is what he sees in Nadja, and it makes him greedy and impatient. The inspiration he gets from her is so much more important than whoever she actually is: the muse is a medium, a vessel for something separate from herself. Her only use is the inspiration that she gives, and Breton becomes clearly uncomfortable whenever Nadja wants to talk about her own experiences or just her life in general. It ruins his picture of who she is, and doesn’t fit into her role as a vessel. He does seem to understand deep down that Nadja is far from that magical being he has made her into in his mind, and he lets that uncertainty shine through in places, but drops it quickly every time, pushing her right back into what he most wants, or maybe needs her to be. If he had been a little more self-aware this would actually have made for a much more interesting book and a lot less eye rolling.

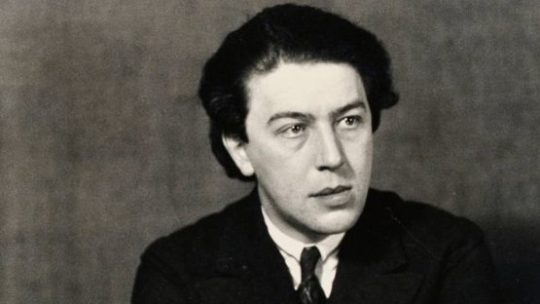

André Breton

Unfortunately, all of this overshadows the things about this book that are actually really, really good. The atmosphere is great, and we get some interesting thoughts from Breton on literature and work, as well as his ideas about chance and how it relates to surrealism. Breton is fascinated by all things and occurrences that cannot be controlled or foreseen but that still gives the impression of a knowledgeable, maybe subconscious hand at work. In these things lie the possibility of liberation, Breton seems to argue, and his idea of ’psychic automatism’ vibes well with this. Surrealism is after all very much about renouncing control and letting go of any mental breaks, and Breton lives with surrealist glasses on, turning the smallest and simplest results of chance into symbols of the un-expected.

While I strongly disagree on the common description of Nadja as a romance novel, the first chapter is a nice read of the kind of life the surrealists lived in Paris, with many mentions of people recognizable from the literary circles of the time. And at least it made me feel like writing.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till engelska av Richard Howard och släpptes 1994 av Grove Press. Recensionen ligger sedan 2017 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recension av Frost av Thomas Bernhard

Erlenbruch im Winter by Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1947

Reading Frost feels a lot like being stuck. Like being pinned between walls, or stuck in a mountain crevice. It’s not just the imagery forced upon the reader by Bernhard, but the very text in itself. The rhythm is steady, it gives you no safe, steady ground to rest, no opportunity to breathe a bit easier. Wherever you turn, you’re met by these sentences, unrelenting, methodic, as if hewn from rock. Words accumulate on top of each other, become new ones that when repeated line up like thick walls. Mirrored in this is the town of Weng, trapped in a hollow among the mountains, oppressive.

Trapped there with us is the painter Strauch, as well as our unnamed narrator, a medical intern working for the painter’s estranged brother. The Intern has been sent to Weng on a secret mission, to assess and report back on Strauch’s health to the worried, but emotionally distant brother. And Strauch proves to be a piece of work; the world he inhabits is a self-centered one where all roads lead back to himself. He is, of course, absolutely insufferable. He craves the pure, the good and untouched, but instead consciously presses on into suffering, and so manages to be self-indulgent through denying himself any indulgences. If there’s anything Strauch gets excited about, it’s his perception of himself as a bitter, eccentric man, suffering his way through life. ’I’m quite reconciled to the fact that everything about me is diseased. In the grip of illness’, he says, and I’m pretty sure that he’s not just reconciled, he’s savoring the thought of it, wallows in it. This notion of his own misery has rooted itself so deeply in Strauch that it has pushed him far beyond reality.

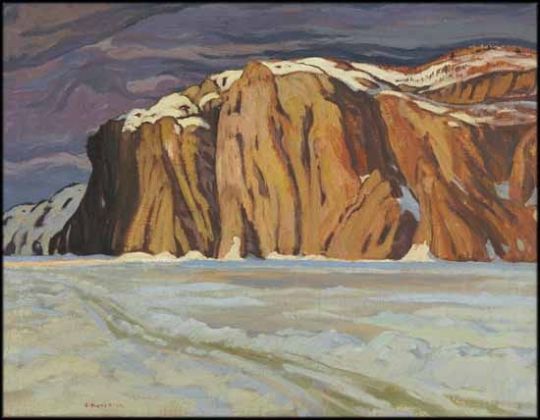

Mazinaw Lake by A.Y. Jackson, 1924

Bernhard’s way of shaping dialogues is new to me. The only way for us to reach Strauch is through the Intern. When narrating, the Intern sometimes gives us the painter’s words in quotes, sometimes he retells them, and it gets hard to distinguish the intern’s thoughts from what comes out of Strauch’s mouth. The impressionable narrator turns more and more into a mouthpiece for the painter’s chaotic mind, and it seems like we first and foremost get to learn a lot about Strauch. His ramblings are poetic and pleasing to read at times, and sometimes they’re genuinely interesting, but mostly they’re just that: ramblings, aimless and erratic. Strauch has only one direction in mind, that of his own inevitable end. All this turmoil teaches us a lot about him, but it does get frustrating to read, and feels a little like trudging through endless marshes. It takes up large parts of the book, and I early on made the mistake of trying to search for meaning in what he says. It’s exhausting, but this search for something real and solid in Strauch’s great mire is so tempting, and that’s the very real trap threatening to engulf the Intern. Because what does looking for substance in that which doesn’t mean anything do to the observer?

And with that question, Strauch fades from his spot as our main character. His thoughts and fears occupy a large part of Frost, but it all ultimately has to be brought to us through, and colored by the hands of the Intern. He, who has barely mentioned his own life as an aside, who was only to act as a messenger, suddenly turns inwards somewhere along the line. He starts taking form. Has he ever really observed himself before? Unlike Strauch, the Intern has a family, work, even friends, but still he seems alienated, completely disconnected from his own self. He is a man who has always simply let things happen to him while passively accepting it all, but since coming to Weng he can’t sleep at night.

Thomas Bernhard, Obernathal by Sepp Dreissinger, 1981

In the presence of the painter, the Intern’s passiveness gives way to another, less subconscious one. Strauch thinks himself into passivity, he’s stuck, frozen in place, ’dominated by himself’ as the Intern puts it. He’s disgusted by instincts and what he sees as the feral, bestial sides of life that he does not participate in. But while it’s tempting to draw the conclusion that the painter is responsible for the Intern’s newly found self, we’ve seen these things before. It’s been present in Frost from the very first page, the dislike of humanity and all that is alive and breathing. It’s been present in the Intern. Something has been resting in his chest, and it has at last gotten enough nourishment to break out.

Bernhard intrigues me. There are several stretches of Frost that become tiresome to read and doesn’t feel like they contribute much, but his way of writing is amazing, and he carves out a very claustrophobic form that in my opinion carries the entire book. The fact that this is only the first one he wrote only makes me more curious to see how he would evolve over time.

(I’ve switched between two different translations while reading this one; the english one by Michael Hofmann, and a Swedish one by Jan Erik Bornlid. They differed enough that I had a difficult time settling for one of them, but I eventually ended up reading the Swedish edition. This translation is very intense, the words hit harder and come across a lot more emotionally effective, but it’s also somewhat more muddled than the one by Hofmann. It’s hard determining how good a translation is without being able to read the original, but I definitely felt like reading Bornlid’s version felt closer to being trapped in a frozen mountain crevice.)

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till svenska av Jan Erik Bornlid och släpptes 2013 av Bokförlaget Tranan. Recensionen ligger sedan 2016 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

0 notes

Text

Recension av The Unrest-Cure and Other Stories av Saki

illustration by Edward Gorey, though not for this particular book

Finishing this book I am left with several pages of fun quotes copied down in my notebook, but also a lingering feeling of disappointment.

The short stories collected in The Unrest-Cure are seemingly Saki’s chance to get even with the world he grew up in. The characters are petty and vain, desperate to be cosmopolitan and to be the envy of their peers. They go to India to shoot tigers so they can show off the skin to their friends, invite rich relatives to expedient lunches, and have names like Philidor and Octavian and Loona. This kind of behaviour is, of course, unacceptable, and so the troublemakers of Saki’s mind take it upon themselves to subject these people to a change of pace.

Unfortunately, most of the stories don’t really stand out from the rest. It’s the same point being hammered home over and over again, often in the same way and by similar characters. All stories are variations on a theme: someone or something disturbs the idle life of English socialites, who are in for a rude awakening from the usual state of things. It’s an interesting subject that’s ripe for biting humor, but the further into the book I get, the fewer the laughs are. About half-way through I’ve had my fill of the sly never-do-good characters, the witty children, the very structure of it, even. It’s clever… but that’s pretty much the extent of what I feel about this book. I don’t actively dislike it, I just leave it feeling uninspired and happy to move on.

In fact, I feel like The Unrest-Cure would very much need such a cure itself. It often feels so self-assured, so comfortable in the set scenarios and characters and somehow so satisfied with its own rebelliousness, that it turns more superficial than it is defiant. It becomes a series of theatre plays that all share the same stage, props, and actors, and that seldom strays from the same angle. Sure it’s a lot of fun in parts, but soon I desperately long to shake up The Unrest-Cure, even if only to see if there’s anything there when the backdrop cracks.

Saki (H.H. Munro)

I’d say that the one story that woke me up and managed to engage and fascinate is Sredni Vashtar, a story about a sickly little boy who, when kept back from living out his emotions and imagination, starts projecting all things deliciously forbidden onto an animal, the god-like ferret Sredni Vashtar. Finally, we get a drastic cure, one that’s maybe the only actual cure in the entire book, the one antidote to the stagnant life that Saki lets these sophisticated people represent. Sure, they have been inconvenienced all throughout the book, and the mischief in many other of the stories has scandalized them and made them bring out the smelling salts, but in Sredni Vashtar, it is finally time. They have stifled any signs of integrity and creativity for long enough with their luncheons and their small talk. Sredni Vashtar is vengeance, and a satisfying one at that. Finally, some colour is forced onto these grey ladies and gentlemen, and this time it’s blood red.

Edward Gorey is an interesting choice of illustrator. His style always has this perfect way of communicating unease in a very simple way; Gorey doesn’t need to draw anything elaborate to make us understand what he’s getting at, and his many books where the drawings do the bulk of the talking are testaments to that. His illustrations to The Unrest-Cure are, as expected, very good, but I never really get the sense that this collection actually needs to be illustrated. Gorey was good with this particular time and social class, but the stories and the book as a whole doesn’t actually gain much from being accompanied by these drawings, and as a reader I didn’t feel like they told me anything I couldn’t get from the story itself.

Speaking of social classes though, it’s pretty unclear which one is targeted here. The stories themselves often speak of ”the middle class”, the blurb on the back mentions ”the upper classes”, and the cover itself resorts to calling it ”polite English society”. To me, in another part of Europe and another time with a somewhat changed class system, it sounds like upper middle class, though today it might just as well be some general contemporary anxiety about fitting in and being accepted in a rigidly normative idea of what a presentable existence is supposed to be.

Unfortunately, The Unrest-Cure isn’t too concerned with overhauling those ideas, and I guess that’s what ultimately makes it kind of boring. Why so comfortable? Obviously, all literature doesn’t have to overturn the world, and it’s probably unfair of me to expect this of random books I pick up on the strength of their illustrators. It’s just that, for a book talking about unrest-cures, the unrest it creates is a somewhat shallow one. In the end, status quo is still maintained, and I don’t feel like I’ve been cured at all.

Utgåvan jag läste släpptes 2013 av New York Review Books. Recensionen ligger sedan 2016 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recension av Hopscotch av Julio Cortázar

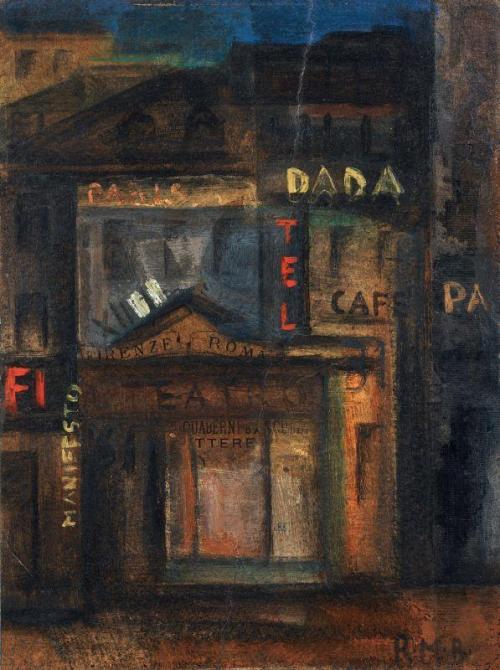

Dada Manifesto by Robert Marcello Baldessari, ca 1922

”What good is a writer if he can’t destroy literature?”

This is the first work of Cortázar’s that I’ve read, and while it might not have destroyed literature, it certainly hasn’t bowed to the traditional form. With it’s inventive structure and Oulipo-like games I should’ve absolutely loved it, but I have to say that my feelings are mixed.

Oliveira, sometime narrator of Hopscotch, mentally and physically fluctuates between Paris and Buenos Aires, reading, drinking, looking for something. Often it’s exactly as clichéd as that sounds. The intellectual expat navigates through the two cities with the help of metaphysics, alcohol, and various groupings of friends who are all ”given over to the reading of Carson McCullers, Miller, Raymond Queneau, to jazz as a quiet exercise in freedom, to the unrestricted knowledge that they […] were failures in the arts”. I’m not going to blame you if you just rolled your eyes and thought something along the lines of ”…fucking beatniks”, but most of the time Cortázar manages to save it all from being too tiresome, and what he loses in content, he makes up for in atmosphere and form.

His writing has a rhythm to it that clearly owes a lot to Cortázar’s interest in jazz, with repetition, quotations, and experimental parts interspersed with Oliveira’s meditations. Sometimes it’s a little too on the nose, but overall I kind of wish he would’ve been more consistent with the jazz inspired style (then again, consistency can make for some really boring jazz). I do love how the narrative won’t really settle, jumping between first and third person, creating the feeling that we’re both inside and outside of Oliveira’s head, looking into and out through his eyes at the same time. It’s clearly a mess in there, but at least it’s a pretty one. I’ve been scribbling down a lot of passages that have rolled off the pages in an especially beautiful way, and there are many of them. Somehow, the whole is lesser than its parts in this book. The experimental bits, the jazz, the word games, the nonsensical little poems, they’re all amazing on their own, but when combined all together and made to carry a narrative, they lose a little of their edge. The good parts get watered down by the long monologues and chains of thought that end up god knows where, and after gathering up the ball of thread and finding my way back through the labyrinth again enough times, I’m more tired than I am satisfied.

Duo, Piano and Cello by Hugo Wetli

It’s not that the ”story” itself is bad, even though so much of it feels unnecessary. The dynamics and relationships between many of the characters were extremely interesting, and I started feeling at home with Cortázar’s voice, with Paris and Buenos Aires, with Étienne, Wong, and the others from the Club. Eventually, even a lot of the irritation that I felt towards Oliveira and his constant metaphysical ailments gave way to pity (he would have hated me for that). Maybe that’s the first step to actually tolerating or, god forbid, even identifying with him. The character that I really couldn’t swallow was Oliveira’s mistress La Maga, and as an extension all the women in the book. Maga is the type of female character only a man could write, innocent as a little girl but still woman enough to be desired, a woman who simply feels instead of thinks, who goes to Paris to ”confront life” and lives in the here and now. It’s just so boring. Not to mention that all the women of Hopscotch are marked by some warped image of femininity; they cry, they gossip, they don’t understand literature. They could have been so much more than that. As it is now, La Maga is clichéed and tiresome, and her most interesting form is when she’s not actually present, but rather exists as a part of the anchor that has twisted itself around Oliveira’s ankles, an anchor made up of her, other (mostly dead) lovers (Oliveira only seems able to take an interest in what heads towards destruction), and Paris itself.

Basically, Hopscotch is copious amounts of caña, poetry, and crying women doing quirky things, and I, too, want to roll my eyes at Oliveira and Maga, but I also really badly want my own pathetic little club with a pathetic little name like ”The Serpent Club” where everybody thinks they’re an intellectual, drinks whatever they can get their hands on, and makes way too much noise in way too small apartments. I love it, and I absolutely despise it, because it’s such a cliché, and because the cliché still somehow manages to reach me. It’s all just so damn appealing, failures in the arts, pretentious losers trying to live up to their own expectations. Cortázar has struck a tender spot, a somewhat disfiguring bruise that I’ve just barely accepted as existing on my body, and I dislike him for bringing my attention to it.

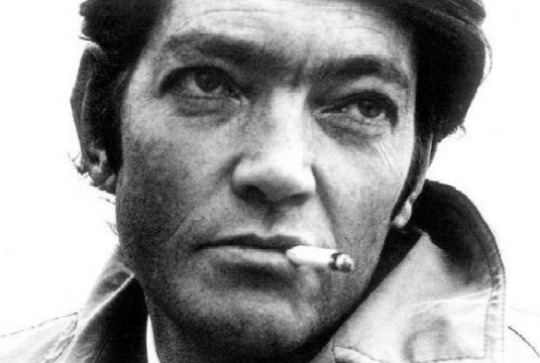

Julio Cortázar

Hopscotch is a book of fragments. Some of them come together to form a coherent narrative, some resemble notes scribbled in the margins, often reflecting on literature, writing as an action, and especially on a hopeful idea of writing fragments that will turn into a complete picture, a ”total comprehension” when read. This could of course be read as a key to the rest of the text. It could also be read as complete nonsense, or both.

As a matter of fact, a lot of Hopscotch constantly balances on the line between insight and nonsense (and it’s a pretty shit balancing act, with the performer regularly planting an entire foot on one side).

Exactly how much of a total comprehension you get from Hopscotch depends a lot on in what way you read it. I’d recommend the second, longer one, that requires you to jump back and forth through the book. It is a lot more coherent than the beginning-to-end method, but then again you could read it any way you want and still create a whole out of it, simply because you’ve been given all of the pieces, and you don’t need to fit them all together in the ”correct” way to end up with the entire puzzle. So go ahead, costumise it.

I’m tired of this goddamn book, it’s been following me around for months, adding to the weight in my bags, being in the way on coffee tables. I guess I’m a masochist, because I’ll keep it, and I’ll read it again, in some new sequence.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till engelska av Gregory Rabassa och släpptes 2013 av Pantheon Books. Recensionen ligger sedan 2016 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recension av Two Crocodiles av Fyodor Dostoyevsky och Felisberto Hernández

Odeon Suite III by William Scott, 1966

Something completely absurd has happened in Dostoyevsky's The Crocodile - not only has a man (and a civil servant at that!) been swallowed whole by the side show beast, he's also still alive and well inside of it - but it clearly isn't insane enough to pop the personal bubbles of the characters experiencing it. Hardly anyone manages to look at the situation without drawing up a narrative that fits their own opinions. No one takes it at face value, and their reactions are mismatched with reality. Both the incident and the suggested solutions are twisted into tools of propaganda, personal and political, and some are so skilled at this that the thought of a man living in the stomach of a crocodile earns no more reaction from them than perhaps a raised eyebrow - it's even predictable, really, inevitable. Objective reality is put aside: after all, what good is reality if it doesn't serve a cause?

And so, the story of Ivan Matveitch being devoured by a crocodile turns into a debate on how it could benefit the economy, how it's proof that Russian culture and values are obsolete, and whatever else people care about. What does this crocodile and the man inside of it mean for Russia?

Through this, Dostoyevsky wrestles with a problem that has survived in Russia for centuries: is the Russian identity Western, eastern, or just uniquely Russian? Dostoyevsky fought the perceived influence of Western ideas in the 1860's, and we still see a similar ideological fight play out in the Russia of today. In The Crocodile, nearly everybody's out to convert the country into something new and "civilized", whether the focus lies on economy or culture. Many of the characters seem to long for being acknowledged by the West, to join "the European", somewhat reminiscent of the more recent identity crises befalling many former Soviet Republics after the fall of communist rule. There's an idea of the west and Europe as sophisticated and successful, as well as a sometimes conflicted wish to belong. Dostoyevsky appears more than fed up with public opinion on how Russia should become more cosmopolitan, more European, and even more patriotic characters wish for Russia to adopt Western capitalism.

The characters are absolutely wonderful, but we all already knew they would be, seeing as this is Dostoyevsky. It's fun in that dry, deadpan way, and the narrator is wonderfully detached. Blows are distributed to greed, vanity, and pride.

Felisberto Hernández

Even though Dostoyevsky's crocodile takes up most of the pages in this slim edition, it's not the only one there. As a matter of fact, it's not even the best one of the two short stories paired up by New Directions into Two Crocodiles.

In the last twenty pages, a very different story unfold. An artist tries crying in public on a whim, and soon discovers the merits of false tears. This Crocodile belongs to Felisberto Hernández, an author I'd heard of but never read, and it is very, very good. The atmosphere is meticulously crafted, and Hernández manages to give us a lot by telling very little, a talent he shares with with many South American authors of his time. The reader does nearly as much work as the author here: we get small, half-remembered details, and get to glue them together however we see fit. It's beautiful, the way a vivid painting is, and while you could certainly read it for the imagery alone, it also explores the idea of emotions as an act of violence. The artist wants to somehow prove to the world that he is "capable of great violence", and it is violent, forcing the strangers around him to take part in a situation that is otherwise private and almost shameful, to confront them with a man crying. It made me want to cry in front of strangers too, just to force my existence on them.

While both of these stories are great, I have a hard time finding a reason for them to be combined like this. Dostoyevsky's Crocodile is a political caricature, and Hernández's Crocodile feels a lot more intimate and quiet. The edition itself had several issues with editing, and the quality of the paperback isn't too good. On their own however, these stories are amazing.

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till engelska av Constance Garnett och Esther Allen och släpptes 2013 av New Directions. Recensionen ligger sedan 2016 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

#two crocodiles#the crocodile#fyodor dostoevsky#felisberto hernández#book review#bokrecension#literature#litteratur

0 notes

Text

Recension av The Passion According to G.H. av Clarice Lispector

Progression by William Scott, 2000

”I’d’ never before had the courage to let myself be guided by the unknown and toward the unknown: my expectations preconditioned what I would see. They weren’t previsions of a vision: they were already the size of my concerns. My expectations closed the world to me. Until for several hours I gave up. And, my God, I got what I didn’t want. I didn’t wander through a river valley - I had always thought that finding would be fertile and moist as a river valley. I didn’t realize it was the great un-finding.”

Struggling against words and definitions themselves is quite bold for a book. There’s a need for form and meaning, and therefore a need for certain limitations. And yet, the G.H. of the title is struggling. This need of hers to interpret reality has been dragged into the light, and now she’s confronting her ways of shaping the chaos into something manageable and forcing things into form.

In christianity, the Passion refers to Jesus’ last few days in the world. It’s agonizing, and it is very significant. It’s a period of great suffering. And what could be more of a Passion than encountering undefined reality and the very Thing of life? When even our label of "disorganization" is a limitation, since that means that the thing inherently can be organized again, then we need to cast off more than our feelings of ease in order to face the world.

For G.H, it’s all triggered by her being confronted with the empty room of her maid, and suddenly being presented with such a contrast to her own reality that she is jolted wide awake. G.H's world has always meant taking a step back from it. Now, instead of her doctored, meticulously arranged and designed reality, her ”fear of ugliness”, she meets something so plain and sharp and naked that it turns in some way feral. It’s a space that refuses to consider her gaze, and it's untouched by human-imposed form.

This violent and sudden awareness is forcing G.H. to shed her skins and expose something fully Nature and instinct. The world is reclaiming itself from the grip of her words, becoming fully its own, and the process of her great devolution begins. To enter the world, she has to lay off all that which separates her from the primitive.

Clarice Lispector

There is something quite Lovecraftian about this. Like his, often unnamed, protagonists she is exposed to the enormity of reality. The horror of glimpsing something so much larger, so much more ancient. In some sections, the cosmic horror is palpable: ”with fright and loathing I was feeling that ”I-being” was coming from a source far prior to the human source and, with horror, much greater than the human.”

It's horrifying and fascinating and crawling and maddening, and it can be felt nearly constantly throughout the book.

Lispector doesn’t try to obey the language, she uses it to her will, to tell what she wants to tell. The translation by Idra Novey is impressive, I can’t imagine it was an easy task. The language is being difficult, it doesn’t accommodate to the reader. Her stream-of-consciousness style of writing varies its beat, slurs its words. It is not made for you, the reader, it fights back when trying to appropriate it. In a way, we're encountering that same alien space that G.H. does. Sometimes the text turns completely erratic, it is written as if in the middle of experiencing it, an account of an on-going rapture. Looking back and going through it at the same time, G.H. is still too close to the wound to see it from afar, and so instead of a birds eye view we get the grounded view of the cockroach or the larva, level with life and the world.

The further into the book, the less human the logic is. It reminds me of the delirious notes I leave myself sometimes in the middle of a train of thought: enthusiastic, but nearly impossible to understand. I so very much want to share what I’ve found but I can only explain it from the far-away place I am already in. I try to show a new language I’ve discovered, but I can only tell of it in that very language.

Bañada en Lagrimas by Helena Almeida, 2009

In some places I found myself wishing for it to make more sense. I would read on wanting it to finally tie all the loose ends together, because things that don’t make sense are inconvenient, I can’t sum them up and fit them into a simple and beautiful whole, and therefore I cannot own it for myself. I want to take part of Lispector, to use her and devour what is hers, make it mine mine mine, but this is struggling against my tries. She doesn’t want to give her words to me in neat pieces for me to consume, and it’s making me frustrated. Slowly, Lispector taught me to let go, to not consume and assimilate, but to receive without understanding or seeing. I’m thankful for that.

And my god is it beautiful. There were sections that moved me to tears.

If you read this at the wrong - or maybe right? - time, it will just be absolute nonsense. I think I might be reading this at a time when it isn’t. Maybe nonsense is good? Maybe nonsense is meaning without limitations. Maybe it’s without OUR meaning, but still has its own, real meaning.

Sometimes I think I don’t rate books on how much I enjoy reading them, but on how much they make me want to write. And Lispector FORCES me to write. She seems to awaken that compulsion to write something, anything. For now, this will have to do.

”Ah, prehuman love invades me. I understand, I understand!”

Utgåvan jag läste var översatt till engelska av Idra Novey och släpptes 2014 av Penguin Classics. Recensionen ligger sedan 2015 ute på mitt Goodreadskonto.

0 notes