Link

‘The arrangement of the bones shows the three-year-old – named Mtoto after the Swahili word for child – was placed with legs tucked to chest, and perhaps wrapped in a shroud with their head on a pillow, before being gently covered in soil...

“It’s incredibly rare that we gain access to such a snapshot of a moment in time, especially one so very ancient,” she added. “The burial takes us back to a very sad moment … one that despite the vast time separating us, we can understand as humans.” ‘

0 notes

Text

“The young Marx analyzed the dehumanizing effects of industrialization in some of his writings of the mid-1840s. The essence of humanity, he contended, was 'free, conscious activity,’ a versatile and even artisanal creativity that ‘forms things in accordance with the laws of beauty.' If I create 'in a human manner,' Marx writes, I make something that bears the mark of ‘my individuality and its peculiarity’; I delight in satisfying your need, and my personality is ‘confirmed both in your thought and your love’; I realize ‘my own essence, my human, my communal essence.' The ultimate aim of work is not just production, but the flourishing of a good human life.”

From “Comrade Ruskin” by Eugene McCarraher, here.

0 notes

Photo

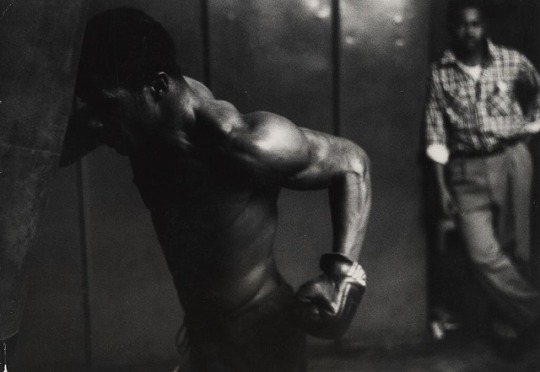

Dom Hans van der Laan

Church of St Benedictusberg Abbey, Mamelis in Vaals, 1956 - 1968

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The idea that God sustains everything in being by his love is known as the doctrine of Creation. Whatever the new atheists may imagine, it has nothing to do with how the world got off the ground. In fact, Aquinas himself thought it perfectly reasonable to hold with Aristotle that the world never got started at all, but existed from all eternity. He was not of this opinion himself, since the Book of Genesis seemed to rule it out, but he saw nothing inherently implausible about it. The doctrine of Creation is not bogus science, as old-fashioned 19th-century rationalists like Dawkins assume. As Turner argues, it is really about the extreme fragility of things. Aquinas believes that everything that exists is contingent, in the sense that there is absolutely no necessity for it. God made the world out of love, not need. Its being is purely gratuitous, which is to say a matter of grace and gift. Like a modernist work of art, or like someone contemplating his own mortality, the world is shot through with a sense of nothingness, one that springs from the mind-warping awareness that it might just as well never have been. The Creation is the original acte gratuit. Aquinas does not think we can get a grip on it as a whole precisely because we cannot get a grip on its opposite, nothingness; but he does think it reasonable to ask why there is something rather than nothing, as some philosophers do not. And since he thinks that the answer to this question is God, this, Turner argues, is the reason he holds that the existence of God, while being in no sense self-evident, can be rationally demonstrated.”

- From Terry Eagleton’s splendid review of Denys Turner’s biography of Aquinas.

0 notes

Photo

Dominican Nuns playing in the snow in front of modern architecture. Pretty much my ideal photo.

Dominican Convent (1969) in Ilanz, Switzerland, by Walter Moser

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Let us suppose you are a married person with children. If you are relatively happy with your life, if you enjoy spending time with your children, playing with them and talking with them; if you like nature, if you enjoy sitting in your yard or on your front steps, if your sexual life is relatively happy, if you have a peaceful sense of who you are and are stabilized in your relationships, if you like to pray in solitude, if you just like talking to people, visiting them, spending time in conversation with them, if you enjoy living simply, if you sense no need to compete with your friends or neighbors - what good are you economically in terms of our system? You haven’t spent a nickel yet.

However, if you are unhappy and distressed, if you are living in anxiety and confusion, if you are unsure of yourself and your relationships, if you find no happiness in your family or sex life, if you can’t bear being alone or living simply - you will crave much. You will want more. You will have the behaviours most suitable to a social system that is based upon continual economic growth.”

John Francis Kavanaugh, “Following Christ in a Consumer Society”, p. 47.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kreuzkirche (1963-64) in Ludwigsburg, Germany, by Heinz Rall

129 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Very interesting construction with concrete columns and bricks.

Władysław Pieńkowski: Dominican Church and Monastery, Warsaw, Poland, 1982

http://sosbrutalism.org/cms/19037782

Photos: Traper Bemowski 2013 (CC BY 3.0) / Mzungu 2011 (CC BY 3.0)

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like this a lot. Part of me would like some color - in the glass perhaps, but the wood adds warmth.

arch. Leopold Taraszkiewicz; S.Josef church; 1958; Gdynia, Poland

605 notes

·

View notes

Text

“For Lúthien was the most beautiful of all the Children of Ilúvatar. Blue was her raiment as the unclouded heaven, but her eyes were grey as the starlit evening; her mantle was sewn with golden flowers, but her hair was dark as the shadows of twilight. As the light upon the leaves of trees, as the voice of clear waters, as the stars above the mists of the world, such was her glory and her loveliness; and in her face was a shining light.”

— Of Beren and Lúthien

280 notes

·

View notes

Quote

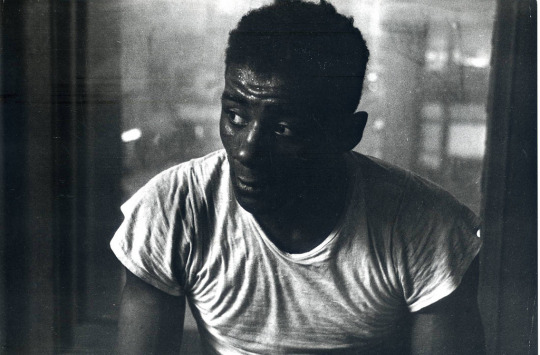

The aesthetics and kinetics of boxing made it uniquely suited to Catholic devotional culture before the Second Vatican Council. The corporeal brutality, the physical perseverance required of participants, the physical wounding that inevitably resulted, the ubiquity of blood—all these defining characteristics of the sport appealed to values central to the Catholic “culture of suffering” of the early and mid-20th century.

For Catholics formed within a religious economy that equated physical suffering with spiritual redemption, a boxing match enacted the central spiritual mysteries of the faith—the imitatio Christi personified in a boxer’s willingness to endure suffering for a greater cause, the Stations of the Cross in his perseverance through round after round of punishment, the stigmata in the gashes and abrasions that collected on his body as a fight wore on, and Christological death and resurrection each time a boxer was knocked down and managed to rise back to his feet.

From “Why boxing was the most Catholic sport for almost 100 years” by Amy Koehlinger.

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Other times, I’ll have a family that’s been told, “Just stay in hope. Just stay in the joy of the Lord.” But they’re noticing in themselves that they’re really distressed. They’re anything but joyful or hopeful, and they’re not feeling faithful, and they’re worried that maybe their feelings are going to be taken as a lack of faith. And if they’re thinking in these terms, they’re also thinking they could be responsible for their child’s death. And that’s where bad theology can do genuine harm.

I’ll ask them, “Do you remember when Jesus was on the cross?” They know the story, and I’ll remind them of the thief who said, “Don’t you know who you’re talking to?” And what did Jesus say to him? Jesus said, “Today you’ll be with me in paradise.” From the cross—death was going to happen—Jesus spoke a word of comfort and hope that is reliable. “Today you’ll be with me in paradise.”

But from that same cross, the same Jesus cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Jesus gives us permission, by his example, to simultaneously hope—to hope in the kingdom, to hope that he has overcome death, to hope that death is not the end of the story—and to lament, to say, “I feel so alone. I do not know where you are. I feel so abandoned. Where are you?” If Jesus can do that on the cross, surely that gives us permission to feel what we need to feel and to not think that that’s somehow going to disrupt the goodness of God.

- Ray Barfield. Mockingbird Interview.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“It wasn’t sudden. He was born four months early. The organs didn’t have enough time to mature. He just wasn’t ready for life. But he held on for more than two years. He was such a happy child. He laughed so hard when you rocked him. We called him ‘Bibi,’ because his older brother couldn’t say ‘baby.’ Toward the end, he was learning to stand on his own. We honestly thought he was going to make it. But his immune system was just too weak from all the medication. And his lungs were too weak from all the machines. He couldn’t survive. I had a hard childhood growing up. This place makes you tough. Nigerians and cockroaches will be the last living things on this planet. I can remember being nine years old, and sitting down with my brothers to make a plan when we ran out of food. Our only idea was to drink a lot of water. So I’ve always had to be strong. When my brother died, I couldn’t mourn. I was the oldest in the family. I had to hold it together and make arrangements. But not this time. After Bibi, I decided that I don’t ever have to be strong again. That was my child. I can’t button this one up. Either I allow myself to be weak, or I’m never going to get through it.”

(Lagos, Nigeria)

4K notes

·

View notes