Quote

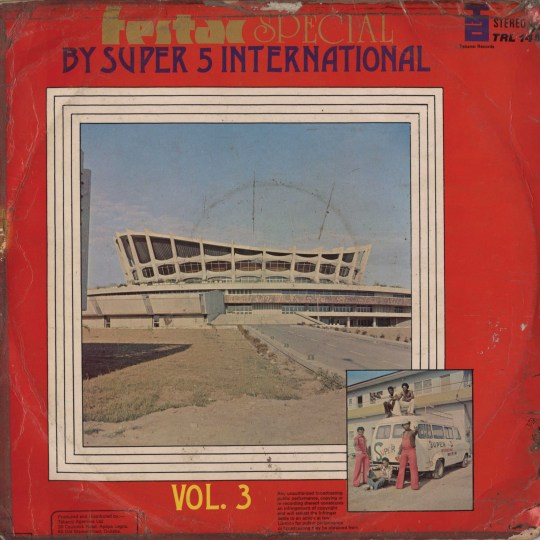

“Through FESTAC, Nigeria’s empire of signs was pegged to petroleum. During this high point of oil politics and prosperity, money became the measure of cultural value”.

Andrew Apter, The Pan-African Nation: Oil and the Spectacle of Culture, 2008

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“The US is the one country in the world that can push Pretoria to make honest reforms before our land is pushed into disaster. The United States is rich. The United States is powerful and its people are concerned with evil things. Just this spring they go out and buy a record from a group called U.S.A For Africa . . . But we listen to the lyrics and we wonder: what is this? 'We are the world,' the stars from

America sing. But who is the world? Where are the singers from Africa, Europe, the East, the Third World? They are all American singing 'We are the World.' Oh truly, we say, 'America' is the world!”

Miriam Makeba quoted in The Voice of (Which?) Africa: Miriam Makeba in America, Safundi: The Journal of South African and American Studies, Volume 13, Issue 3-4, 2012

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“Bachana Mokwena (an exiled poet and student activist) was supposed to be acting as guard at the door of the main student union hall where people were to gather: he was standing on a chair at the entrance waving a coke bottle and shouting: 'Welcome to the liberated Zone.'”

J. Seidman, Thamsanqa Culture is a Weapon of Struggle, SA History Online

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“She [Miriam Makeba] sang in Nairobi at Kenyan independence, in Luanda, at Angolan independence, at the inauguration of the Organization of African Unity in Addis Ababa. For Samora Machel in Mozambique.”

Stokely Carmichael, Ready for Revolution, 2005

1 note

·

View note

Quote

“Next thing I know Fela’s talking on the mike again and he’s got me by the hand and he’s cursing out the military — and there were military guys in the club! I wanted to get the hell off that stage with quickness ’cause those cats don’t play! Man, Fela was fearless, but I was sweatin’… what this guy DIDN’T call the government… and he wouldn’t let go of my hand! The people were cheering him on!”

Randy Weston, African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston, Willard Jenkins, 2010

15 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“It is a discredit both to the organization of the International Secretariat to certain specific governments—I shall not name them just yet—that they have permitted political vendetta to intrude into the process of objective selections of individuals for the Festival. The sole criteria should be, surely, the creative and intellectual stature of participants at the Festival. I am ashamed, as an African, to disclose that this has not been so.”

Wole Soyinka interview, Afriscope, 1977

0 notes

Quote

“Fela's protest against national corruption and multinational exploitation, held amid the world's largest single gathering of African and Afro-diasporic arts, laid bare the problems facing modern Africa. Through his music, words, and the cultural space he created, Fela reminded the Afro- diasporic delegates who greeted each other with raised-fist Black Power salutes that the majority of citizens in the host country—let alone Africa—had no power. The era of praise songs for the new African nations was over. In the struggle for the soul of the continent, Fela believed the artist must become the critic, the musician must sing and play the truth.”

Robin D. G. Kelley, Africa Speaks, America Answers: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times, 2012

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“There must be understanding on our part of the aspirations of the Arab people and more positive support of their efforts toward peace in the Middle East.”

Standard Oil Company Of California, in a letter to shareholders.

quoted in "Arab Oil Tactics" New York Times, 7 February, 1974

1 note

·

View note

Quote

“Mbeki decided to go, and ‘indeed,’ he told me, ‘when you get there, you don't really want to be seen, because there he appears onstage, Fela, he's only wearing underpants and his saxophone.’ Those who knew Mbeki in Nigeria say he loved Fela's music—its roots, its rhythms, and its politics. Fela took all the groovy ideas Mbeki had encountered in Europe in the 1960s and reinvented it as authentic African culture; he broke the rules, not in the permissive West but in supposedly patriarchal, conservative Africa—in a military dictatorship to boot. He was somebody spectacularly uncolonized, somebody free.”

Mark Gevisser, A Legacy of Liberation, 2009

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“The array of folks [in Lagos] was incredible. For example I’d have breakfast and my table-mates might be Louis Farrakhan, Stevie Wonder, Queen Mother Moore, and a heavy Sufi master named Mahi Ismail. Imagine me hanging out with those cats! When he arrived Stevie came into the hotel with his guitar, walked in the lobby, sat down and started singing and playing his guitar.”

Randy Weston, African Rhythms: The Autobiography of Randy Weston, 2010

0 notes

Quote

“Culture starts with the people as creators of themselves and transformers of their environment. Culture, in its widest and most complete sense, enables men to give shape to their lives. It is not freely received but is built up by the people. It is the vision of man and of the world and is thus systems of thought, philosophies, sciences, beliefs, arts and languages. Culture is essentially dynamic: in other words it is both rooted in the people and orientated towards the future.”

Pan-African Cultural Manifesto, Organization Of African Unity: First All African Cultural Festival, Algiers, July/August 1969

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“Here was the problem: Obasanjo’s government had recently become enamored of the young revolutionaries of the Soweto Student Representatives’ Council (SSRC), who had led the June 1976 uprising and were now in exile—and whose charismatic leader, Tsietsi Mashinini, had taken to slamming the ANC at every turn. Mashinini called the ANC ‘corrupt’ and ‘extinct internally’ and said he would even take money from the US Central Intelligence Agency if it was willing to help him. The ANC responded that he was the stooge of ‘counter-revolutionary forces,’ but Mashinini, only 19, was articulate and passionate, and was ‘snapped up by a world eager to put a face on the now-famous Soweto uprising,’ as the historian Gail Gerhart puts it. After Mashinini's high-profile tour of Britain and the United States, the Nigerians brought him to Lagos, which swooned.”

Mark Gevisser, A Legacy of Liberation, 2009

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

“Oil for dollars, art for dollars, the equivalence was confirmed by the spectacular scale of the festival itself. Nigeria's oil-wealth—black gold indeed—appeared as a form of money-magic, which emanated from the ground and was tapped by the government... Briefly stated, Nigeria's goal as a developing country—to build an efficient and productive economy—was implemented from above, by a state which swelled the civil service, imported commodities and expensive technology, while promoting little indigenous production.”

Andrew Apter, “FESTAC for black people: oil capitalism and the spectacle of culture in Nigeria,” Passages, 1993

0 notes

Quote

“For the first time as a result of calculated policy, rather than as reaction to war, four Arab petroleum-producing states last Tuesday temporarily halted the flow of their oil to consuming nations. The embargo, which lasted one hour in Iraq, Kuwait and Algeria and 24 hours in Libya was called to pro-test the 25th anniversary of the founding of the state of Israel. The stoppage itself had little more effect on world energy trade patterns than a squall in the Mediterranean. Its implication that oil has become a political weapon, however, was ominous. The target was the United States, seen by the Arabs as the chief supporter of Israel.”

William D Smith, Oil As A Political Weapon, New York Times, 13 February, 1974

0 notes

Quote

In the year that I was born, 1973, a rise in oil prices caused an increase in Nigeria’s balance of trade and payment figures. Crude oil came to account for an exceptionally large portion of the federal revenues, at the expense of the agro-allied industries and the manufacturing and service sectors. Thus, the familiar story of how we gradually abandoned cocoa, cotton, palm oil, groundnuts and other agricultural products to embrace the new, the euphoria of oil that carried us dancing and drumming to the doors of the International Monetary Fund. Three years before that, our principal foreign exchange earner was already petroleum; the euphoria was well in the groove before my generation came along.”

Yemisi Ogbe, “Birthing the American”, Chimurenga Chronic, December 2013

0 notes

Quote

“Gil and Veloso subsequently recorded albums inspired by their experiences in West Africa and by the new Afro-Brazilian cultural movements. Veloso's album Bicho (1977) features a song based on Nigerian juju music, 'Two naira fifty kobo' (a typical cab fare in Lagos at that time), which invokes a divine force that 'speaks Tupi, speaks Yoruba' and affirms the cultural affinities between Brazil and Nigeria. Bicho also included several upbeat disco-inflected songs like 'Odara,' a Yoruba term commonly used by Candomble practitioners to signify 'good' or 'positive.' In response to the so-called ideological patrol of the traditional left, Veloso slyly advanced the notion of an 'odara patrol' to stigmatize the Eurocentricism of his critics on the Left and the Right.... these songs also located Afro-Brazilian culture at the very center of Brazilian modernity, instead of assigning it a pre-modern role as the bearer of cultural purity. In the same year Gil recorded Refavela, a brilliant and far-reaching reflection on Africa and Afro-Brazilians within a contemporary diasporic perspective.”

Christopher Dunn, Brazilian Popular Music and Globalization, 2001

1 note

·

View note