Text

my brief history with magic

I did not grow up with magic.

Mom ran The Salty Dog’s Pollucks and I mostly just got in the way. I tried to help and she let me keep the tips I earned, but she never wanted me to get comfortable. She didn’t want me figuring out how to make a living doing that. She saw in me something more.

She was the first in a series of people who saw in me something I still do not see and sacrificed what little they had to see me succeed. The second was Professor Nenzo at Murann University.

I’ve heard more than one rootless traveller claim “not all who wander are lost,” but as I stumbled onto the hallowed campus of Murann University, I was a lost wanderer. Had it not been for Professor Nenzo intervening, I honestly do not know where I would have ended up.

That wise old gnome gave me a book. That’s all it took. He handed it to me with a twinkle in his eye and a gnowing smile splitting his beard.

I have never felt connected to anything. I have spent most of my life not feeling completely alone but actually completely alone. That’s not to say I haven’t had friends along the way; I have. But as life has separated us on our journeys, I have not mourned them. Losing their presence has not wounded me the way I see loss wounding others. Nothing has ever felt permanent, everything has felt temporary.

Magic changed that. It connected me to forces unseen — powerful, dreadful, beautiful and unfsthomable forces. They are bigger than me, yet they are inside me. They fill the hollow in my heart — and I am connected to all that I see. I do not command these forces, I beckon them. They are the unseen strings that hold the natural world together, and I pluck them like a harp.

I’m still alone, but I’m no longer lonely. I am a warlock and I a living, breathing part of this realm. I am not the rain, but I am a rain drop. I am not the forest, but I am a tree. My role is yet to be defined or identified and I prepare for that role by practicing my craft and waiting for my cue.

0 notes

Text

For the lack of a word

I woke up this morning feeling hollow.

These are the days people often accuse me of being sad -- but it’s not a sadness I feel. Perhaps it’s a form of sadness, a brother or sister or cousin of Sadness, but should someone ask me, “do you feel sad,” I would say “no. I don’t feel sad. I feel nothing.”

But most people don’t want to know. They have their own problems, their own headaches, their own traumas. They don’t have the time or energy to take on the extra weight of the innkeeper’s son.

I wish I had a word for this. There must be one. Something that says “I’m alone in this world, completely disconnected from everyone and everything and I have great certainty that if I walked into the ocean and let the current take me away, not only would I stop feeling this way, absolutely nobody would miss me.”

Melancholy is the only word I can think of that comes close to this feeling, but it’s not quite right.

0 notes

Text

the pirate and the piney

Skyler told me her story today.

There was a dwarf family ice skating on the pond, so we sat out of view and ate the lunch I had brought. It was the children’s first time out on the ice. As they struggled to keep their balance, as they fell and got back up again, their laughter bounced off the ice. Their parents were out there with them, patiently showing them how and holding their hands when they needed it.

Even from our perch, we could tell the parents were tired. Dad moved a little slower than he wanted, Mom would correct her slouch and stand a little straighter. They were stiff, tired, and sore from a hard week’s work, but they were here now because this is what was important to them. This is what they lived for. This is why they worked so hard.

“I never knew my father,” I said, then quickly corrected, “well, I mean, I can count on one hand how many times we’ve been in the same room.”

Skyler produced a flask from a satchel. “This was given to me by . . .” She scrunched her nose as she tried to remember, “Sadgen Doz, a hunter out of Velen.” She poured me a cup and then one for her. As she crammed the cork back into the flask, smacking it with the palm of her hand, she warned, “it’s a spice whiskey. It’ll warm you up, loosen you up and clear your sinuses.” We toasted Sadgen, thanking him for the drink, and burned ourselves from the inside out.

I could barely hear her laughing over my coughing.

“You tried to warn me!” I laughed.

“I did at that.”

“I grew up in a tavern, you’d think I could handle just about anything!” My cheeks were red, my entire face was pulsing.

“Your mom run a tavern?”

I nodded, “The Salty Dog’s Pollucks, in Tulmene.”

“I think I’ve heard of that.”

“It’s a nothing hole in the wall.”

“You’ve just described all of Tulmene.”

It mas my turn to laugh, “I did at that.”

“That means,” she sipped her whiskey, “your father was . . . a merchant -- no, a sailor! No, a pirate!”

“We have a winner!” I cheered a little too loudly.

She shushed me, shooting a glance down to the pond. The dwarves hadn’t heard us -- or didn’t care.

“The son of a pirate!” Skyler marveled. “Anyone I know? Anyone I heard of? Someone infamous? Wait!” She held up a finger. “What did you say your name was? Ó Cuinn?”

I waited.

“Ó Cuinn, Ó Cuinn, Ó Cuinn . . .” A dreadful wave of recognition washed over her face. “Not Captain Ó Cuinn!”

I nodded.

“Cruel Captain Coin was your father!?”

“Still is,” I nodded, “I think. Haven’t heard one way or the other in a couple of years now. And,” I added, suddenly feeling defensive, “he wasn’t always ‘Cruel’ Captain Coin.”

I don’t know why I felt defensive. I don’t know why I felt like I had to explain him to her, but I did.

“He was a good guy.”

“Oh,” her eyes widened mockingly, “he was one of the good pirates.”

“Hoarding wealth was not the game he started out playing, but . . .” I trailed off. We both knew where that thought ended.

“Freedom for the wolves,” Skyler said, softly breaking the silence, “often means death for the sheep.” She sipped her whiskey. “It’s the sheep’s job to clothe the wolf. If they can’t do that, they feed the wolf. If the sheep finds a way to live and keep its wool, keep its skin, the wolf says the sheep is cheating. The sheep says, ‘but I’m just doing what you’re doing,’ and the wolf says ‘know your place,’ and sics the pack on it.” She gave a quick shrug and a smile. “But what do I know? I’ve have rejected human society and live alone in the forest.”

“Do pineys have the same problems as humans?”

“We’re all the same,” Skyler said with disgust. “Elves, dwarves, orcs, humans or pineys. Everyone wants to be on top and in order for there to be a top, there has to be a bottom.”

“I think,” I nodded, “I mean, I don’t know, but I think that’s what made my dad set sail. There’s different stories I’ve heard, how he stowed away on his first boat, how he became a cabin boy and how he took over his first ship. The one thing they all agree on, though, is that he wanted to help others. He targeted ships from kingdoms that could handle being robbed. If he could do it without spilling blood, he would. He paid his crew well, took care of his ship, squirreled a little away for a rainy day and when he came into port, he would just give the rest away. At some point . . . At some point he began to believe everybody owed him something. He was changing their lives, saving them and what was he getting return? Shouldn’t every port celebrate his arrival? Shouldn’t the taverns give him a place to stay, food to eat, ale to drink? Forget brothels charging him and his crew, what woman dare say ‘no’ to him?”

I don’t often talk about my father. It always leaves me in a fouler mood than when I began.

“You carry so much with you,” Skyler prodded, “don’t you?”

“I guess so.”

“You measure yourself to him.”

I nodded.

“Again, it’s so different with pineys. In the traditional human sense of the words, I know who my mother and father are and they loved me very much but I was raised by village. I was everyone’s child and everyone was my family. There were far fewer specific roles anyone played. It was by looking at everyone, and comparing myself to all my surroundings, I was able to learn who I was. I didn’t measure myself to someone, I measured myself to everyone.” Then with a smile and a flare she said, “and this is who I decided I am.”

“It’s a good choice.”

“Less of a choice and more of a discovery.”

“But you chose this,” I said, “this form.”

“Because it’s who I am.” She tapped her heart. “Inside and out.”

“So,” I prodded back, “if pineys are so great, why are you out here? By yourself?”

“Ugh,” Skyler’s face soured. “It’s a long story.”

The dwarf family was still skating. “I’ve got time.”

“I met a boy. Human boy. Dark hair and dark eyes. Loved him. Fell madly, deeply, uncontrollably and foolishly in love with him. The village didn’t like him, he was human. Can’t trust a human. He tried to win them over but they weren’t having it. They rejected him. So I appealed to the magic of the forest and became a woman for him.” Skyler winced. “Not for him but things might be different if I had met a girl. Humans let all these organs and things define them way too much but -- I will say -- when I saw my reflection for the first time, it was like I was seeing me for the first time. This is who I was born to be. We ran away, he and I. Married under the full moon. Got pregnant.” Skyler stared into the bottom of her cup. “Lost the baby. Tried again and again and it never happened. Then one night he left me a note and I never saw him again.” Her laugh was a mocking laugh. “It was too much for him and I never saw him again -- well, that’s not true. About a year later I found a gnawed up skeleton wearing his cloak, so . . .” She looked at me. Her eyes swirled with melancholy conflict. “That’s me.”

“Wow,” I said, eager to lighten the mood but profoundly appreciative that Skyler would share this with me, “he just became my absolute least favorite person.”

Skyler laughed.

“Did he have a name?”

“Alec McQuillan.”

“No! You fell in love with someone named Alec? Alec! Really?”

Skyler laughed.

“Rubbish name for a rubbish human being.”

“I think it’s partly why they won’t take me back, why they cut me off.” Skyler theorized. “They tried to tell me. They saw him for what he was and I turned my back on them.”

“Wait. Does that make your Skyler McQuillan?”

“Fuck no.” Skyler almost did a spit take. “The night he left me, he lost every part of me. I pruned him out of me.”

“Well, speaking for humans . . . and for men, I’m sorry.”

“He ruined me for both. Never again.”

Then she gave me a look, a testing glance, that said that might not be entirely true. Neither of us lingered on it.

“You don’t have to sit up there!” A big, surly voice boomed off the ice. We looked over the dead, leafless bush we sat behind. The dwarf family was waving at us. “You can come down here and skate with us!”

So we did.

0 notes

Text

ignorant thoughts on ignorance

I am not a smart man. Before I go any further, it must be recorded that not only am I not a smart man, I know I am not a smart man.

I’m just smart enough to:

Know how ignorant I am.

Be embarrassed at how little I used to question things.

Engage in a really riveting argument with 8 year olds.

That being said, why are we so bad at accepting beliefs that are different than the ones we already have? I don’t even mean when someone tries to convince you their way of seeing the world is the right way. Trying to convince someone they are wrong is a fool’s errand. That is a journey of self-discovery each person must take on their own.

No, I mean the discovery that somebody believes something that is different than what you believe. I grew up with a very simple set of beliefs that can all be boiled down to “nobody is going to look out for you like you are.”

It was only recently that I started asking questions that may or may not have any provable answers. How did we get here? Why are we here?

Magic is real. I did not grow up believing in it, but I have seen it, I have stolen knowledge of it, and I have begun practicing it. I can feel it when I use it. I feel a connection to something bigger than me, but what is it? Is it simply an aspect of nature we haven’t fully explored and discovered yet? Am I connecting to a forgotten, unknown deity?

The Piney, Skyler tells me, do not believe in gods or goddesses. They are beings of magic, though. Who they are and what they can do comes from the forest. It’s something, she says, anyone can open themselves to, but it is not easily and readily apparent. It takes time. Skyler is cut off from this magic.

She will not tell me why or how that’s possible, only that she does not think she will ever be welcomed back. She is an exile from her community and from the forest. It has softened her, she says, weakened her. She feels more human than piney these days. But she could never blend in as a human and the pineys will not have her. She is a person without a people.

“Which is fine,” she says. “The complete and utter hostility pineys have for anyone who isn’t one of them -- who doesn’t believe what they believe, who maybe worships a god or goddess or who lives by a code that doesn’t respect the forest and every living thing in it as its top priority or tenet . . .” Skyler shook her head, looking more exhausted than disgusted. “They can be a very warm an open and accepting people, willing to help in whatever way they can . . . as long as you’re one of them.”

It’s what keeps them in the woods, what keeps them separate -- not that they would be greeted with open arms should they choose to come out. It’s hard to imagine the different races of men and their myriad of belief systems having much room or acceptance for the pineys.

But why? If a person is not hurting someone else, what does it matter what they believe? We all speak different languages and while that can lead to misunderstandings, they are rarely anything beyond a mild frustration. Is a world view anything other than just a different way to describe something? Is it not just a different language?

We love to learn other languages! How many times have I seen someone’s eyes light up when they learn a foreign phrase? They’re suddenly able to express something new — not just make a new sound but an actual, new idea. Or they’re finally able to express something they’ve always known, always felt, but their language doesn’t have a word for it.

Yet when we presented with an opportunity to learn how another culture explains or understands aspects of life, we get angry. We get defensive. We build walls. We see it as a challenge or attack on us personally.

I’m not a smart man, so maybe I’ll never understand why, but WHY!?

0 notes

Text

Skyler

“It was as if she granted me the ability to see music.”

I hadn’t mean to fall asleep. I hadn’t planned on it. But I must have, because I was suddenly and surprisingly waking up. I was leaning against a tree and sitting cross-legged on a rock to my right was The Piney.

I cleared my throat, “I’m, ah . . .” I was embarrassed. As much as any writer wants the world to read their work, we don’t actually think the world will -- and, should the world actually choose to read it, we do not want to be present when it happens. “I’m not a poet.”

The piney did not look up. “But is that how I made you feel?”

I wanted to be clever, I wanted to be casual, but the truth just clumsily tripped out of my mouth. “You were magnificent.”

There was a tilt of the head, a flick of the eyebrows and a dimpled little smile that said this was something the piney already knew. “Thank-you. And these are me?”

My sketches never looked cruder, more elementary, than they did in that moment.

“Yeah, I’m . . .”

“They’re good.” The piney was being kind.

“Thank-you.”

Closing the journal and tossing it back to me the piney asked, “you’ve been here every day this week. What do you want?”

“I wanted to apologize.”

“You already did that.”

“Yes, but . . . I wanted to see you again.” I sat up, pulling my legs closer. “I wanted to talk to you.”

The piney nodded. “I saw that in your book. I don’t think . . .”

I could see where that thought was going. If I didn’t hurry, if I didn’t stick my foot in the way, this door was going to be closed to me forever. I quickly blurted, “What’s your name?”

The piney paused. It was rude and unexpected of me to interrupt, but it worked.

“Skyler.”

“It’s nice to meet you Skyler. My name’s Gareth Ó Cuinn.”

Skyler nodded. “I remember.”

“And I’m nobody, really. I help run the inn in Tulmene -- The Salty’s Dog’s Pollucks?” I floated the name out there to see if there was a reaction. There wasn’t. “I work nights. So . . .”

“So you can spend your days stalking girls in the woods?”

I wanted to clarify that I was not stalking her and I would leave her alone if she asked me to. I would be disappointed, but I would. But instead, what I heard myself saying was, “are you a girl?”

“What the fuck do you think I am?” Skyler shot back, eyes ablaze.

“I’m sorry! I’m sorry, I don’t know! I read about pineys and . . .” I could feel my mouth moving, my lips trying to form words, but nothing but absolute silence coming out.

I saw Skyler stiffen and then soften. “Sorry. I . . . It’s tiring, explaining it over and over. Every traveller, every merchant, every lost boy in the woods has to know and . . .” Skyler shrugged, “it’s something we are going to need to keep talking about. It’s one of the reasons the pineys have secluded themselves but it is becoming one of the reasons we need to come out of the wood.”

I remained silent. She was warming to me. Her icy demeanor was thawing. And me speaking up now would only ruin that.

“We,” Skyler motioned back and forth between us, “come from the same people. From long, long ago. One day, a group of humans went into the woods and never came back. They discovered something there. The forest embraced them, made them its own and the magic of the forest changed them. We pineys are descendants of those humans. Our nails are wood, are joints creak in the cold and in the springtime flowers grow in our hair.” Skyler smiled a beautiful, unguarded smile. “Our eyes are bigger are our limbs are longer. We’re often mistaken for dryads or elves. And our skin . . .” She held out her hand.

I could see what she was showing me. It almost looked like wood, like the bark of a tree. If she stood still, one might think she was a carving. Skyler leaned forward, extending her hand closer. I reached out and touched it, running my fingers down the length of hers and resting them in the palm of her hand. Her fingers were cold but her palm was warm -- just like mine.

“It’s gotten us into trouble. We look sturdier, like we’re made of harder stuff but . . .” Skyler pulled away, rubbing her fingers together. “Turn a page too quickly and I’m still going to get a paper cut.”

“And,” she added, “I am a woman. I was not born a woman, but I am a woman now. Inside and out.”

“And . . .” I could tell this was a conversation she wasn’t entirely comfortable with, so I added, “we don’t have to talk about this if you don’t want to, is that a choice you made?”

Skyler nodded. “We don’t have genders. We’ve grown past that. We don’t see ourselves as men and women, male or female -- not just us, but also things. Humans need everything to fit inside a box and that box needs a label other humans can see from a mile away and . . . it’s so unnecessary.”

It’s an idea I’m still trying to understand.

Skyler could see I was struggling and offered an example. “You met someone in the woods. What else matters? How they treated you? How you treated them? What extra, pertinent information is gained by saying that the person you met in the woods was a man or a woman? It only matters because in your society you treat different labels differently. Depending on what box that person is in and what label they have, you expect different things from them.”

This is true. There is no arguing that. However, I had to ask, “how does piney society work then?”

“We expect the same things from everybody.” Skyler said simply. “Everybody is expected to pitch in. Everybody is expected to help. We don’t change our standards because of a label someone made for us centuries ago.”

“But . . .”

Seeing where I was going, Skyler pointed at me and agreed. “Yes. People are born different, with different temperaments and personalities and skillsets. We don’t expect our engineers to be musicians or our teachers to be soldiers. We find what you are good at and then we help you find your place. Why anyone would be destined or predestined to do or be anything based on their genitalia is . . ." Skyler laughed.

It instantly became my quest to make her laugh again. I shook my head. I couldn’t explain it. It doesn’t make sense and the sooner we as a society except that, the sooner we can move on and become something stronger, mightier.

“Which,” Skyler took in a deep breath and let out a slow, curling stream of steam before continuing, “takes us to procreation. When I said we don’t have genders? I meant it. We are all born the same. Inside and out, we don’t have any of the things humans like to call men’s things and women’s things. When it comes time for us to reproduce, we are able to choose which role we want to fulfill. There is a ceremony. It is private, between you and the forest. And afterwards you emerge with . . . the parts you need to play your part.”

“Are you able to change back, if you wanted to?”

“Many do.” Skyler nodded. “Once the deed is done, once the child is born, these parts no longer serve a purpose. Not for us.”

“Why did you keep it?”

She pulled her coat closed and looked away. I made her feel uncomfortable.

“Sorry.”

“The short of it is I’ve been cut off. I am allowed in the woods but I am not granted access to the woods. I can see its magic but I can no longer feel it or use it. I must remain this.” Skyler laughed and shrugged, obviously wanting to move away from this as quickly as possible. “There are far worse things.”

The sun was sinking in the sky. I needed to get back to Tulmene.

“I have to go but I’d love to see you again.”

Skyler spotted the sun’s position. “I have to get to work.”

“Can I see you again?” I asked, gathering my things.

Skyler stood. “I’m sure our paths will cross again.” She picked up her ice skates and then, before sliding down the snowy hill, gave me a kind look of warning. “I know you’ve been coming here unarmed on purpose but stop doing that. These aren’t the woods you grew up in. It’s not safe.”

Then she slid away, disappearing into the trees.

0 notes

Text

Pond Sitting, day 3

No sighting today.

Returned early to help Mom at the inn but she still refuses to let me help. She’s getting too old for this life. She needs to slow down. She needs to let others pitch in. But she refuses. “I didn’t work this hard for you to be trapped behind the bar.”

That stubborn, stubborn woman.

0 notes

Text

Pond Sitting, day 2

Just as I did yesterday, I arrived at Fisher’s Pond shortly after sunrise. The sun is getting low and the Piney has not returned.

This really should come as no surprise. The Pineys keep to themselves. I’ve heard merchants talk about them, about encountering a cloaked stranger on the side of the road wanting to buy or sell goods. They never want to barter and they want the transaction to be as quick as possible. If they don’t like the deal, they disappear back into the woods without a word. They will not wait for the rest of your party to arrive, even if means a better deal for them. They will not follow you into town and they have never been seen in town.

They Pineys want nothing to do with us and I’ve gone this long without ever having seen one. I’ll be lucky to see one again.

0 notes

Text

Pond Sitting

I arrived at Fisher’s Pond shortly after sunrise. I packed myself a breakfast, a lunch, and a dinner. I sat on the shoreline, sketching and making my way through a stack of books, waiting for the Piney to return.

She did not.

At sundown, with no sight of the Piney, I packed my things and returned home.

0 notes

Text

What Little We Know About Pineys

It appears the person I met yesterday was a Piney.

Not a lot is known about the Pineys, it appears. The Tulmene Library only has half a page on them. To be fair, to call the Tulmene Library a library is being generous -- or slanderous to actual libraries, I suppose.

But what little I was able to gather from that single half page was that we do share a common ancestry. The Pineys were once human. The magic of the forest transformed them into something more. They keep to themselves and not a lot is known about them.

EXCEPT it appears the Pineys do not recognize genders. While we have men and women and all the hes and shes, hims and hers that go with them, they do not. They are a genderless society.

I do not know how that works but I am fascinated by it. The Piney I met was beautiful and graceful and possessed every characteristic that I find aesthetically pleasing and appealing. And in writing about that person, I used “she” and “her” and, quite honestly, I don’t know how I feel about that. The person I met, I would describe as a woman, but their culture does not have label, so I should not label them as such.

I would really like to know more. I wonder if she the Piney will be back at the pond later?

0 notes

Text

At Fisher’s Pond

A new chapter of my life demands a new journal. This is the sixth journal I have started and I would highly recommend, for continuity’s sake, you read the first five in chronological order before reading this one as I am not really one to repeat myself or explain myself if I have previously done. “I don’t chew my cabbage twice,” as the saying goes.

I was feeling melancholy today and so took a walk in the woods. The forest was quiet, save for the snow crunching beneath my feet. I grew up surrounded by those trees; chasing dreams, monsters, and whatever other wild things my imagination cooked up.

I had no plan, I had no destination in mind. But my feet instinctively knew the path we were on. I wove around trees, climbed over rocks and slid down embankments until I stood overlooking Fisher’s Pond.

So many summer days were spent there, swimming, fishing and surrounded by friends. As we grew older, so many summer nights were spent there, staring up at the stars as we plotted our futures.

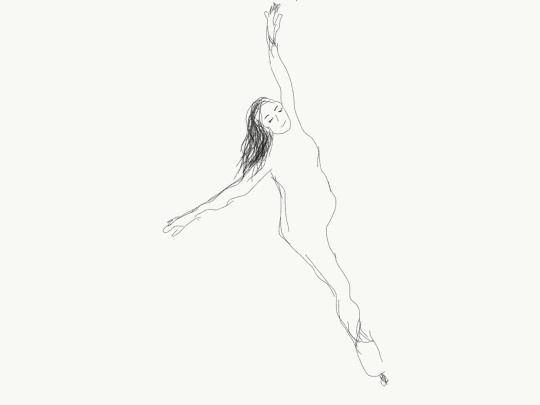

I shouldn’t have been surprised to discover someone else there, it’s not a secret place — yet there I stood, at the crest of the hill, surprised to discover someone else there. There was someone skating down on the ice. I slid down the hill, using what trees and branches I could grab onto to guide my descent, until I stood on the shore of the pond.

Her eyes were closed, she had no need for them. There was nothing they could tell her she didn't already know. She was cut off from the world, alone on the ice and communing with nature. The wind pushed and pulled at her, plucking her hair and blushing her cheeks. She twisted his way and that, sometimes sailing straight ahead, sometimes backwards and sometimes through the air. She was smiling — that's how I knew I was smiling. It was as if she granted me the ability to see music.

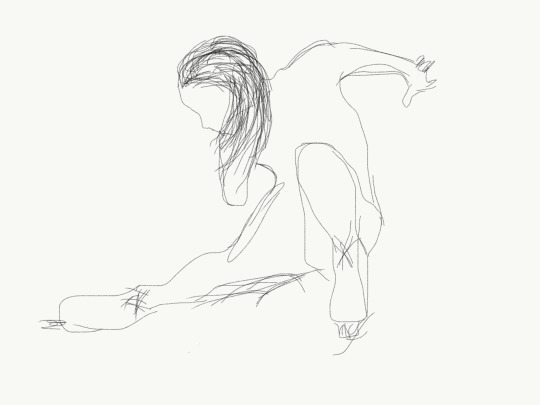

Realizing this made me also realize I was intruding. This was a private moment, one I had no place in. I turned to leave but my boot caught a patch of ice and I went sliding out onto the pond.

I shouted in surprise. She screamed. I tried to stop myself, to right myself. She fell, sliding across the ice towards me, screaming in a language I had never heard before.

I sat up, holding my hands up. “I’m sorry! I’m sorry! I’m unarmed!” I tried to throw my cape open to show that I wasn’t even carrying a weapon.

Her large, swirling brown eyes narrowed. I had thought she was human. But now, face-to-face with her, she clearly wasn’t. Maybe at one time her race was, perhaps we have a common ancestry, but whatever she was, wasn’t human. She was something of the forest. Her skin was pale, but instead of freckled, it was knotted and flecked, like the bark of a poplar tree. And I can’t be certain, but it almost sounded like her joints creaked when she moved, like the boughs of a tree.

Sitting on the ice, she pulled her knees against her chest and pointed defiantly at me. She shouted at me in her native tongue, a lively and bouncy language that sounded almost Elvish, but was accentuated with pops, chirps and creaks I couldn’t place.

“I didn’t mean to intrude,” I said as I stood. “I’m sorry.”

She didn’t move.

“Do you speak Common?” I asked. She didn’t respond. “Goblin?” I repeated the question in Goblin.

She made a face that said she was wholly unfamiliar with that language. I tried again, in Orc and when that didn’t work, Celestial.

I went back to Common. “I didn’t mean to . . .” I smiled, a little nervous and not entirely sure how to describe what just happened. “I used to come here when I was little. It’s one of my favorite places.”

“It’s not yours,” she said, “it’s the forest’s.”

“Are you . . . The Forest?” I had heard stories of dryads, sprites and spirits. My mind whirled at who or what I could have just met.

"I am none of your concern,” she glared. “Please leave.”

I tried to take her in, to remember her every feature, that I might describe her later and someone, anyone, might be able to help me discover who she was. I nodded and I smiled and I backed away.

“I’m Gareth Ó Cuinn, by the way,” I called before turning to the shore.

“I don’t care,” she shouted back.

I laughed. I couldn’t help it. She made me laugh. She tilted her head. I waved good-bye and climbed up and away from the pond. Only once I had reached the crest of the hill did she stand back up. I watched her skate away and disappear into the woods.

I raced back to Tulmene, but not in time to find the library open. My research will begin first thing in the morning.

0 notes