Text

Painting a picture of the history of Filipino Tattoos

A photo of tattooed Filipino men posted on BBC and accredited to Joe Ash

Tattoos are often seen as integral cultural symbols in my different societies whether it be seen as something honorable or dishonorable. Even in the most straight-laced cultures, a tattoo acts as a mark of some form of the person's history and their standing in their communities as well as how people perceive them.

In a lot of modern cultures, the tattoo often have negative connotations, often associated with delinquency or criminal activity. Historically, however, they may have grander and more honorable significance in different societies. The communities that had existed in the Philippines prior to contact with Spain fits this similar pattern.

Before I start

As usual, the Philippines is a diverse country that has different traditions and histories that come from different ethnic groups and states, only being first unified under a government by colonization. Because of this, this post will only be able to cover parts of this culture and may not be able to fully encompass all Filipino traditions, practices, and beliefs about tattoos.

This is also given the fact that more specific information may be harder to come across or may not exist at all in a space I could easily access.

That being said, the general term for Filipino traditional (both precolonial and current) tattoo practices is batok, batik, patik, or patek depending on language or culture. It is also known as buri or burik in several other groups and languages. This word, however, isn't often used for typical tattooing in most modern communities.

The History

From a general understanding of a lot of precolonial Southeast Asian cultures, it can be assumed that precolonial Filipino societies heavily valued tattoos as their neighboring maritime SEAsian countries also had prior to the introduction of Abrahamic religions to the region which often discouraged or even forbade tattooing the skin.

Although this can be assumed, there were no known precolonial description nor record of these tattoos during the actual time period before Spanish contact. There is evidence found in some burial sites however, as discussed by social anthropologist Salvador-Amores in her paper The Recontextualization of Burik (Traditional Tattoos) of Kabayan Mummies in Benguet to Contemporary Practice (2012). In the paper, she focuses a section on the history of burik by explaining the Kabayan Mummies or the Fire Mummies of Benguet, Mountain Province.

An image of one of the Kabayan Mummies uploaded by Dario Piombino-Miscali on ResearchGate.net

These remains had been dated back to the 13th century and are associated with the Ibaloi, an indigenous ethnic group from Mountain Province found in the northern parts of the island of Luzon. This does confirm that tattooing had been important to the people who had lived in this area during this time period as, in Salvador-Amores's paper, it can be noted that the tattooed mummies seem to be prominent with the adults.

I do have to note that the Ibaloi people, who are part of the larger Igorot ethnic group, were not fully colonized by the Spaniards and therefore does not share the similar Hispanic culture and history that a lot of Filipino groups have. They had only fully been integrated into the Philippines during the American colonial period where they and the other Igorots had been properly colonized by American and placed under the rule of the American-controlled Filipino government. (x)

Regardless, this does show that at least some cultures in the archipelago held tattoos with high importance and did not consider them as something negative compared to the modern perception of tattoos.

The first known illustration of tattooed Filipinos, however, was first seen in the Boxer Codex (circa 1590) during the early Spanish colonial period, written and illustrated by an unknown author.

A page from the Boxer Codex (circa 1590), author uknown

This illustration seems to be that of the specific ethnolinguistic group, the Visayans as this page is next to another one labeled as "Biſſaya", a likely earlier spelling of Bisaya that uses the long s (ſ). This aligns with the description given as early as Antonio Pigaffatta, Ferdinand Magellan's chronicler, who consistently describes the Visayans that he has met as painted in his account of their arrival in the islands back in 1521.

The book The Philippine Islands 1493-1898 Vol. XII has compiled different first-hand and second-hand sources about the Philippines during the 15th through 19th century, with Vol. XII focusing on the early 17th century which aligns closely to the Boxer Codex. Within the text, there are several mentions of the "Pintados" or the Painted ones, even having an entire province be called the "province of Pintados".

It isn't made clear who the Pintados are besides the fact that they seem to be hostile towards the Spanish colonizers and had often fought battles with one of the letters even claiming that they had poisoned one of the Spaniards. It isn't until we reach the last part of the compilation which features Pedro Chirino's Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas which I had a hard time finding before but had now found a free and accessible copy. Within Chirino's writing, he explains that the Pintados seem to be a name given by the Spaniards to the Bisayans and further explains it as such:

"The people of the Bisayas are called the Pintados, because they are actually adorned with pictures --not because this is natural to them, although they are well built, of pleasing countenance, and white; but because they adorn their bodies with figures from head to foot, when they are young and have sufficient strength and energy to suffer the torment of the tattooing; and formerly they tattooed themselves when they had performed some act of valor."

Chirino even gives an explanation as to how precolonial Visayans tattooed their skin:

They tattoo themselves by pricking the skin until the blood comes, with sharp, delicate points, according to designs and lines which are first drawn by those who practice this art; and upon this freshly-bleeding surface they apply a black powder, which is never effaced. They do not tattoo the body all at the same time, but by degrees, so that the process often lasts a long time; in ancient times, for each part which was to be tattooed the person must perform some new act of bravery or valiant deed

It is notable, however, that not only did the Spanish not mention any tattoos on other Filipino groups such as the Tagalogs, but a lot of the illustrations in the Boxer Codex do not sport any tattoos at all which makes it confusing as to when had tattoos faded out of cultural significance in these other communities, likely even before Spanish contact.

Lane Wilcken, a researcher who studies the history of tattoos from the Philippines and the Pacific Islands, writes in his book Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern (2010) that it may be possible that the Tagalogs may had lost their tattooing traditions shortly before Spanish contact during the recent islamization of their communities circa 1500 which was and specifically in the polity of Maynila. This may also be the case for the Moros which is a muslim ethnolinguistic group found in the island of Mindanao.

Either way. tattoos became more scarce within Filipino records after the arrival of the Spanish and the introduction of Christianity to the islands, save for some indigenous groups that were not fully colonized by Span like previously mentioned Igorot people.

Because of the spread and dominance of Christian and Islamic customs throughout the country, Batok, as it originally was, was lost to time with the lack of existing artists and cultural relevance tattoos. Tattoos didn't come back to the Filipino mainstream until modern tattoos became more prevalent especially in the mid to late 20th century, similar to its rise in popularity in Western cultures, and even then, it wasn't really what I would consider any traditional and is often negative.

Present Day

Like a lot of other countries, however, tattoos had seen a swing of opinion and is more accepted now as an art form rather than a sign of criminal activity but some stereotypes are still popular.

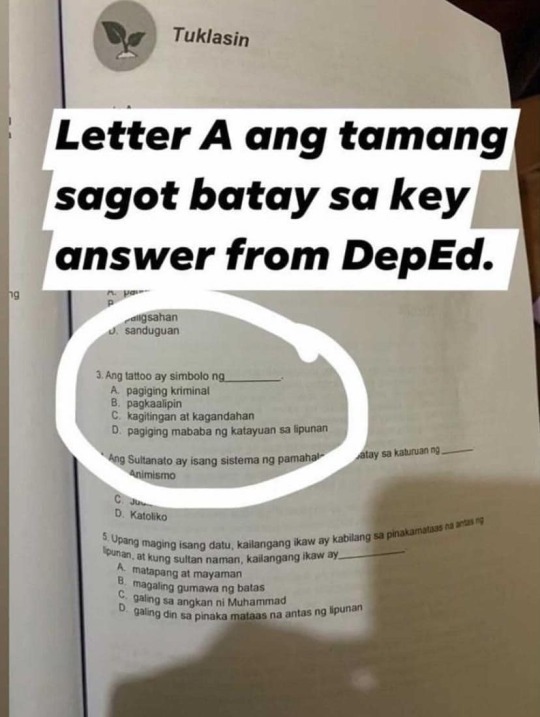

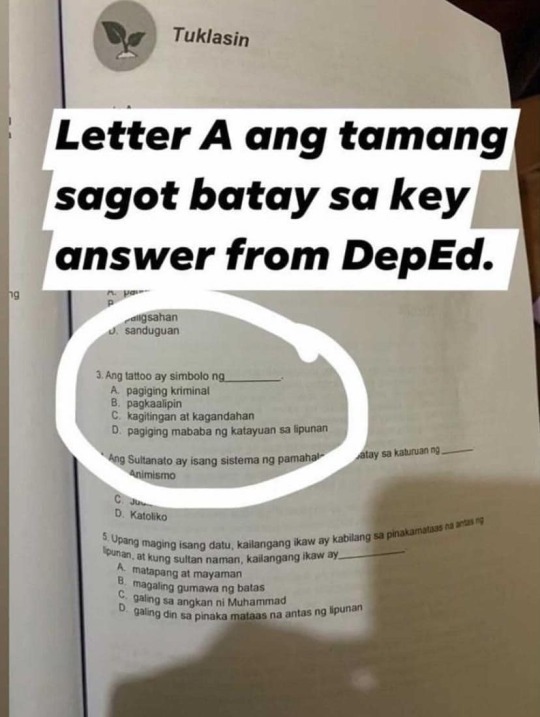

For instance, during the COVID-19 lockdown, the Department of Education provided modules for students to answer at home which would be then collected by the school from door to door. In one of these modules, Lea Salonga, a Filipino singer, complained on November 17, 2020 on her Facebook page of a discriminatory question that was found in one of the modules, pictured below

EN Translation:

White text: The answer is letter A based on the DepEd answer key.

Module text:

3. Tattoos are a symbol of _____

A. being a criminal

B. being a slave

C. courage and beauty

D. having a low standing in society

This controversy caused an uproar online and showed that there are a lot of Filipinos today that don't see a problem with tattoos and even see them as a positive. Two days after the image was posted on Salonga's page, the Department of Education publicly recognized the misstep and had issued that they officially recognized the controversial answer as an error.

It is important for me to note that, just like in a lot of countries, tattoos are typically not accepted in the corporate world and those who have them either have to get them removed or at least cover them up if they get hired at all. There's still a common idea that people with tattoos, if not dangerous, may be seen as unprofessional or even unclean which I do know is a similar thing that other countries may have as well.

As for batok, its comeback in the larger Filipino mainstream didn't return until some time in the late 2000s and 2010s when more international influence had resparked and interest in more ethnic cultures including the precolonial Filipino tattoos specifically because of the internet and the rise of social media. The current batok that we see outside of indigenous communities could be seen as a recreation of the extinct practices within the Philippines with some level of appropriation from related cultures (by appropriation, I mean this in a neutral way not a negative one).

It is argued whether or not the reconstructed practice could be considered traditional at all, but considering its heavy emphasis on the older designs found in historical illustrations as well as designs from indigenous communities that did not have practice eradicated by colonization, some also argue that the modern tattoos that has gained prominence because of modern technology and research is still valuable in a socio-anthropological sense.

As Salvado-Amore puts it

the successive phases and changes in the status of burik tattoos—enabled by the advent of modern technology, the Internet, and mass media—encourage an interaction between contemporary and historical influences rather than an extinction of past practice.

About Apo Whang-Od

A magazine cover of Vogue featuring Whang-Od, a traditional tattoo artist from the Butbut people, a subgroup within the Kalinga ethnic group. (The rest of this section pulls from the same article by Vogue)

Any research about Filipino tattoos, especially in the modern day would be incomplete without any mention of Whang-Od, the most popular traditional tattoo artist from the Philippines.

Apo Whang-Od (b. February 17, 1917, a.k.a. Maria Oggay) is a member of the Butbut people of the Kalinga indigenous ethnic group from Kalinga province, Philippines. She is often known as one of the last mambabatok in the country which earned her fame and recognition internationally. She started her tattooing practice since she was a teenager at age 16, under the mentorship of her father and was the only known female mambabatok during her time.

For years, she was called on by different communities within her locale in order to tattoo important and symbolic tattoos on members of her and different communities after they had received certain milestones. Men were tattooed for different reasons than women as men were given their marks when they succeed in activities like headhunting, which was ritualistically important for the Butbut people while women were tattooed for reasons like fertility or beauty.

Because of American colonization, however, headhunting was prohibited so she was mostly tattooing women from then onward.

She started gaining recognition some time in the mid-2000s to the 2010s after she started serving foreign tourists, although she doesn't give them the more traditional symbols. Non-members of the group are given a set of tattoos that she could tattoo on anyone without any strong connection to the original meaning of the art.

Since tattooing was passed through family and Whang-Od herself didn't had any children, she was known as the last mambabatok for a time which caused concern for the extinction of the practice as she was already in her 90s when she gained notoriety, but she has since started training her grandniece Grace Palicas and later on her other grandniece Elyang Wigan and the two, who are now in their 20s, has since helped their great aunt dealing with their clientele.

Due to her fame, she is often the subject of foreign media and interest, even being invited by Vogue magazine to pose for one of their covers (pictured above) and is now known as the oldest Vogue cover model earlier this year at the age of 106.

Despite her fame and arguably cultural importance to not only the Kalinga people but the Philippines as well as online petitions since the 2010s to give her the recognition, she is not eligible to receive the National Artist award— one of the highest awards given to artists of most artistic fields of which only 81 people had received. Victorino Manalo, Chairman of the National Commission for Culture and Arts (NCCA) explains that this is because her craft, tattooing, isn't covered by the NCCA but by the Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan (GAMBA, en. Award for Crafters/Creatives of the Nation) but there has been some discussion within the commission about this issue which still ended with her being denied. In light of this, she is now currently on the running to possibly receive the GAMBA award.

She has an online presence managed by others and she can be found via Facebook and Instagram.

Tattoos now, from my experience

As I had said before, tattoos these days are not as negatively seen as they were in the 20th century and had received a more positive reputation thanks to the rise of its social experience due to the internet and social media's prevalence in the country. As an art student, in fact, it's wasn't that surprising when I learned that one of my classmates had a tattoo and it was even a full sleeve! Now, as least three had tattoos before they graduated with one of them actually being a close friend of mine who's planning to get more despite their parents' disapproval.

Despite this, I still do have people in my life right now that see tattoos as undesirable and unclean, with stereotypes still being prevalent. I had once heard people speak of them in such a negative way but then make an exception for the artsy type of people? It's odd.

As for batok or batik, I had not seen a lot of people with these tattoos in my own life and had only seen it through articles and images circulated around by other people who I don't even know. I guess it makes sense as most people who do get tattoos similar to batok or batik often do it in tourist-y places or are foreigners who want to get a piece of Filipino culture on their way out of the country.

Besides more culture-focused people, batik or batok isn't as prevalent as some of these articles might make it seem and most typical Filipinos who don't come from these cultures are more likely to either not have tattoos at all or have similar tattoos to those that you may see in other countries.

Either way, tattoos could be so personal to a person and whether it's something as deeply-rooted to culture like batik or if it's just the names of your favorite K-Pop idol, that tattoo is important and has special meaning. Get whatever tattoo that you want or don't if you don't want any at all!

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interact with this post if you think bakla and tomboy are separate gender identities from man and woman

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to the FilipInfoDump!

This is a blog dedicated to posting random things about the Philippines including trivia, media, history, and culture. Here, we will do our best to share information and answer questions about the country.

This blog was started by @maya-chirps as a way to just share Filipino stuff that they had learned from their Filipino history and culture hyperfixation.

Please be patient as there is currently one mod who has to regularly deal with personal health issues. We will get to your questions in due time.

Links

Post Directory

About the mods

FAQ

Sources (TBA)

Tags

filipino history

filipino culture

filipino myths

filipino legends

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tagalog conjugation is pretty easy but it’s all Tue prefixes and suffixes that make my head spin

Learning languages is SO FUN right up until you need to learn conjugation and then suddenly it turns sour real fucking fast

77K notes

·

View notes

Text

Filipino trans men 🤝 Filipino lesbians

Being called a tomboy

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where are all the Filipino trans men who are attracted to men

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Because I never hide my real identity as a tomboy, I still feel animosity directed at me every time I go on dates with a woman. I don't wear skirts and don't use makeup, but I dress respectably. I do wear pants and polos or men's shirts but not men's undergarments, because I believe that no matter how many millions of men's jockeys I might wear, I am still a woman. However I have felt and thought like a "man" for as long as I can remember. My parents, four brothers, and a sister did not even try to make me act more feminine. They were unlike some other parents I know who did physical harm to their children who turned out to be gay or a tomboy.

As a child, I never played with dolls. It was always toy guns and wooden swords and boys as playmates. I was nine years old when I experienced that funny feeling that I now know as getting turned on, toward an older girl. I wanted to kiss her and go to bed with her, but I couldn't tell her, because I didn't know what to do. Schoolmates, neighbors, and playmates called me a tomboy. Although I did not hide my personality as a tomboy, men would still court. me. I do not hate men. I prefer women, because it is a woman who excites me. I have gone out with men to picnics, dance, drinking sprees, but I have never gad sex with a man, unlike some other tomboys who did before they became lovers of women.

Courting a woman is the concern of all tomboys. From my personal experiences, the courting stage is similar to what any man does- love letters or notes, flowers and chocolates, invitations to movies and gatherings, and visits to the girl's family. During the courtship stage, the problem arises not with the girl but with her friends and family. These are the people that causes us headaches, sleepless nights, and heartaches. Rarely do we have girlfriends whose families and friends vote for us. They always disapprove, because they claim it is immoral for two women to fall in love. These are the people who are very much a parent of our society, which scorns and ridicules us as if we are pariahs. These are the people, and many of them are very religious, who believe white is white and black is black, who talk a lot about ethics and morality, and who think they are now somebody because they are not like us. These people treat us like intruders. They are the same people who called you deviant, the kid who appears to be so pious, so moralistic, that they appear not to have sinned at all. They are the kind who teaches their children to scorn and ridicule us.

Throughout the years I have suffered insults and derision. I have been treated with disgust by these people. I have grown callous to their insults behind my back; they dare not say them to my face, because I will always challenge them to a fistfight. I remember years back when my girlfriend and I were walking hand in hand in a downtown area and we passed by a group of men who were just standing there ogling people. One of them made an obscene remark, calling my girl "the whore of a tomboy." I saw an empty soft drink bottle, picked it up, broke it, and turned ack to where the group was sitting. I swung the broken bottle at one of them. My girlfriend was so frightened, she dragged me away form that place, but not before telling them to fuck themselves.

There are still lots of things to be said about lesbian life here in the Philippines. We're lucky here, because we don't get beaten up just because we wear men's clothing. But a tomboy who dresses like a man rarely finds a job that pays well. it is always the low-income positions that await them- security guards, janitors, cooks, messengers, carpenters, vendors."

-"A Letter from the Philippines" by Marivic Desquitado, The Persistent Desire (edited by Joan Nestle) (1992)

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m a Filipino trans guy and I agree. People always expect me to act as this paragon of masculinity, but sometimes I like wearing eyeliner for example, and that doesn’t invalidate my identity!

The concept of non-conforming is unique to your culture and experiences and I love that actually. In the Philippines its sorta expected that if you're gay, you have to act like the opposite gender. So here its actually more non-conforming to be a femme lesbian, as butches and tomboys are more the norm, which is newt to think about

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simbang Gabi: The 9 Days Before Christmas

An image of a red parol from Peakpx.com

The Philippines is well-known for its extremely long Christmas celebration that a lot of foreigners often look at with confusion. Traditionally, Filipinos may start putting up their trees, playing festive songs, and counting down to the 25th as early as September in a season that's colloquially called the "ber months" or the "ber months season" (Petrelli, 2021). This period often lasts up until January or February where some houses may still keep their trees and decor pushing as far as March.

Even with this technicality, however, you'd be hard-pressed to find Filipinos truly celebrating from the very beginning of September genuinely ending it by the end of February. Most often, actual celebrations start after Undas, a period encompassing All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day on the 1st and 2nd of November respectively to commemorate the dead, similar but a lot more subtle than other Catholic countries own Day of the Dead like in Mexico's Dia de Los Muertos and Italy's Giorno dei Morti. This time period is often the start of people doing more Christmas-y things such as Kris Kringle activities leading up to the main Christmas party.

The main markers of the true start in itself is the Advent season, which starts on the Sunday nearest to the 30th in Western Churches like Roman Catholicism and leads up to Christmas ("Advent", n.d.). This is where Catholics would go to Church every Sunday leading up to Christmas to light the Advent Wreath until the final candle on its center on Christmas day on the 25th. As the Philippines is heavily influenced by Roman Catholicism, Filipinos follow the Western start of Advent and most celebrations often fall in the middle of this time period. Even the middle of Advent, however, Filipinos have a waiting period to count down before Christmas - Simbang Gabi.

What is Simbang Gabi?

Simbang Gabi (en. night mass; going to mass at night) is a Philippine Christmas tradition wherein Roman Catholic Filipinos would attend mass nine days every single morning or night before the actual Christmas celebration. Traditionally, the masses were held every morning at 4:00 AM from the 16th to the 24th which would then be capped off by Christmas Eve Mass at night or Christmas Mass on the 25th with its early schedule earning it the name Misa de Gallo (en. mass of the rooster) (Lazaro, 2020). In most dioceses, however, they often have an anticipated mass schedule that start a night earlier than the morning masses (Hermoso, 2022).

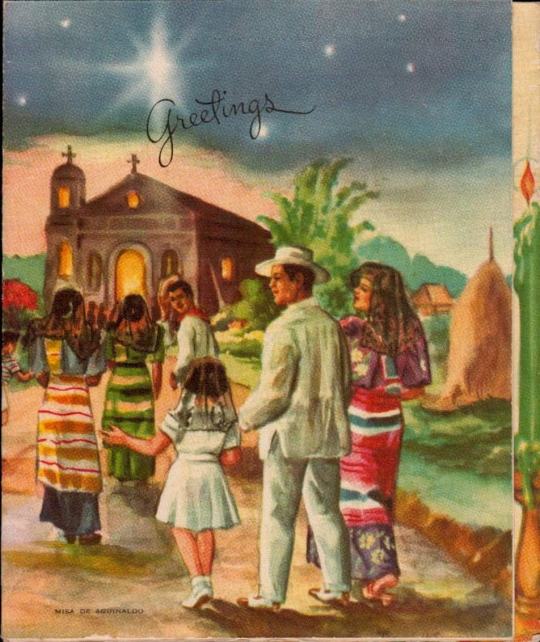

Besides being called Misa de Gallo, I had also heard the celebration being called Misa de Aguinaldo (en. mass of gifts) in some places. This shares the same name as the similar Puerto Rican tradition Misa de Aguinaldo which is also a nine-day mass held in the morning, typically at 5:00 AM which is also deeply-rooted in Puerto Rican Christmas traditions (Álvarez, 2018).

History

A vintage greeting card posted by the Facebook group Vintage Philippine Islands 1920-1959 (2020)

Being a Christmas tradition, it is not surprising that Simbang Gabi could trace itself back to the Spanish colonial period.

A common misconception of its origins states that the practice first started in Mexico. Hermoso (2018) states that it started on the year 1587 by Friar Diego de Soria of the Convent of San Agustin Acolman when he requested the Vatican to allow church service to be held outdoors because of an overflow of attendees during the Christmas time. Pope Sixtus V later approved of this request and even decreed that these kinds of masses be held in the Philippines at the dawn of the 16th of December. What this doesn't account for was that the practice of going to church for the Eve of Christmas dates back to even earlier than the 16th century.

The cover for an English translation and compilation of Etheria's writings by M.L. McClure and C.L. Feltoe, D.D. (1919)

The first recorded instance of Christians celebrating Christmas by going to early mass leading up to the actual date was first written by Egeria (also called Egeriae, Etheria, or Aetheria), a Christian Galician woman who first recorded it during her travels to the Levant where she notes the early morning masses and festivities from the time of the Epiphany to the Nativity. She writes in her letters later called the Itinerarium Egeriae (en. The Travel Guide of Egeria; The Pilgrimage of Etheria).

"Octave of the Festival.

On the second day also they proceed in like manner to the church in Golgotha, and also on the third day; thus the feast is celebrated with all this joyfulness for three days up to the sixth hour in the church built by Constantine (...) And in Bethlehem also throughout the entire eight days the feast is celebrated with similar festal array and joyfulness daily by the priests and by all the clergy there, and by the monks who are appointed in that place (...) and immense crowds, not of monks only, but also of the laity, both men and women, flock together to Jerusalem from every quarter for the solemn and joyous observance of that day."

- Egeria, 381-384; The Pilgrimage of Etheria (trans. McClure & Feltoe, 1919):

The practice of attending early morning masses up until the main festivities of the Nativity was later adopted by more Western Christian communties during the time of Pope Sixtus III when he celebrated what is widely considered the first Midnight Mass at the Basilica of St. Mary Major in Rome, not only stemming from the popularity of the Christians from Jerusalem but also the popular belief that Jesus was born at midnight (The Pillar, 2021).

The prayer spoken within the midnight vigil was then called the "mox ut gallus cantaverit" which translates to "when the rooster crows", aptly named because of the early hours the vigil tended to last which then coincided with the crowing of roosters ("Misa del Gallo: origen, historia y por qué se celebra en la madrugada del 25 de diciembre", 2022). The practice was continued by the Spanish with the name Misa de Gallo (also called Misa de Aguinaldo)which later spread throughout the Spanish Empire and could now be seen practiced in countries like Bolivia, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and of course the Philippines.

There seem to be two variations of this: the nine-day series of masses before Christmas (found in the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela) and the single early morning mass before Christmas day (found in Spain and Bolivia). It isn't clear if Spain and Bolivia simply dropped the nine-day tradition or if the nine-day tradition was restarted in these other colonies, however.

In the Present Day

An image of crowds outside a church during Simbang Gabi uploaded to Wikimedia by Erwin Malicdem

Today, the Simbang Gabi continues to be a popular tradtion for most Filipino Roman Catholics, even those who aren't typically as religious most parts of the year. This is given the fact that a popular belief is that when a person completes all of the nine days, they may receive a wish to whatever they desire. This is such a common belief that Bishop Broderick Pabillo, a Manila auxiliary bishop, had to remind people that the point of the tradition is to remember Jesus and his nativity (Punay, 2016). Besides this, it is also a common challenge among Filipinos to try to complete it as is or see how many days out of the nine could they actually attend.

It is not uncommon for churches these days to hold an "anticipated" mass the night before the actual date starting instead on the 15th and ending on the 24th with a Christmas mass, instead of starting on the 16th and ending on the 25th. This newer tradition had come from the reign of Filipino dictator President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. during the Martial Law years in the 70s, when Filipinos were not allowed to go out after a curfew until 4 in the morning (Macairan, 2023). This allowed more people and especially those who may not be able to start their day early or those who may have other obligations in the morning to attend masses at night time, typically at around 6 PM - 8 PM.

The only large controversy that I could remember about Simbang Gabi was back in 2011 when the event was banned from being conducted within the Philippine Center in New York City. The ban came about because of it supposedly violated Canon Law which prohibits religious worship in unconsecrated ground or in other words places that aren't seen as places of worship. In an article by Adarlo & Pastor (2014), Rev. Dr. Joseph G. Marabe, the at-the-time head of the Chapel of San Lorenzo Ruiz and a priest-in-residence at St. Patrick's Cathedral where the ban took place, explains in an interview with news site The FilAm:

"It’s not allowed by law to have Holy Mass in an unconsecrated place. Worship should take place in a sacred place. That was an explanation but not a decision. The Archdiocese decides."

- Rev. Dr. Joseph G. Marabe, head of the Chapel of San Lorenzo Ruiz in Chinatown, New York (2011)

The ban was later lifted on 2014 after community leader Loida Nicolas Lewis wrote a letter to the diocese to reconsider the ban which led to the return of the almost 30-year-old tradition that year (Balitang America, ABS-CBN North America Bureau, 2014).

Besides being a huge part of current traditions, a lot of Filipinos, and especially Filipino youth, use the event as an excuse to go out during the night to hang out with friends and even go on dates with their partners. It is not an uncommon sight to see a group of teenagers, often wearing maybe less than typical church clothes, by the edge of the Church seemingly attending mass. Whether or not they're actually being attentive is hard to decipher. Either way, this has led to an explosion of memes almost every year just mocking these kinds of people or making fun of their own.

A screenshot of the "Simbang gabi starter pack" posted by user rhapido on 9Gag.com (2022)

Earlier versions of this meme could be seen posted throughout Filipino social media during the early 2010s

A meme posted by the Facebook page FEU Memes (2012)

The barkada (en. friend group) going to Simbang Gabi had been an older tradition that has found a lot more popularity in the contemporary era because of social media. My mother had told me that she used to use it as an excuse herself back in the 80s to hang out with her friends at night time. This may be a continued past time for especially younger people for years to come.

There's also many street foods associated with Simbang Gabi that may not be unique to the event itself but are nevertheless heavily associated with the event due to their widespread sale during this time period. Foods like bibingka, puto bumbong, kutsinta, and other popular rice cakes dominate the scene which definitely satisfy the hungry parishioners who had, most likely, not eaten breakfast or dinner before going to church. With their strong associations with Simbang Gabii and Filipino Christmas as a whole, I might discuss these on a later date.

Simbang Gabi, from my experience

Growing up and living in the Philippines and especially being raised Catholic within a Catholic town named after a Catholic saint and going to a Catholic school named after another Catholic saint, it probably won't shock you that I, myself, had tried to complete the nine days of Simbang Gabi myself. I had attempted it several times with only maybe trying seriously by myself once in my life. It was quite the experience to just try to dedicate yourself into completing a goal to do something for nine consecutive days straight.

My first attempt was when I was in Junior High and it was with my sister and two people who worked for my parents and had helped watch over us. It was something that I always wanted to try doing and especially since I was gaining a lot more independence at the time so what better to try it out without the rest of the family? With adult supervision, of course.

Since we lived quite away from the actual church, the place was already packed even an hour before the actual mass started. There was barely any seats left and even less standing room leading to a huge overflow of people stuck outdoors, only hearing mass from the outdated speaker system that they had erected in place of the old bell tower.

The mass in our church was often done in the dark during the night out of an deliberate and probably aesthetic choice with only the alter being illuminated by the lights. The rest was lit up by the scattered about Christmas decor throughout the church and the church patio. It always felt like going to some liminal space that other nights at church just doesn't give.

Once the mass has been concluded, people rush out of the doors in thick crowds to find their way into the footpaths leading on to the main town streets. Some opt to stay behind to enjoy the food stalls that had pop-up for the night to eat bibingka, puto, sapin-sapin, and palitaw among other things. Some of the teens had decided to raid the nearby small park and playground as a hang-out spot to talk the night away before they rush home for their curfews. Meanwhile others were just rushing to get home as soon as they can, with people lining up to go to the rudimentary parking space that the church created while the others who didn't own their own vehicles forced to compete for the very few commuter vehicles still riding through the night, hunting for passengers.

This was before we had our own car, so we were with the latter crowds of people, trying to peer through the dark streets only illuminated by the scant Christmas lights that still refused to turn off as the night progressed. Every so often, two headlights excite the crowd and a swarm of them start running in anticipation with not care or tact if they would crush children or separate families all to take a seat on the night jeepneys, some the few commutes left after 9.

My sister was an expert in finding her way through it, reaching out to the doors to form a barricade for herself and the rest of us to prevent others from taking our seats before letting herself in. I still think I would've been left behind if it weren't for her doing that out of sheer competitiveness with the crowds.

We settled into our seats and squeezed in tightly to allow other passengers in so we could all go home as soon as we can. It was a tight but otherwise uneventful commute every night with nothing but tired people waiting for their stops and slowly emptying the once packed vehicle. Since we live in the outskirts of the town, we were often the last few and at times, the drivers would transfer us to other jeeps just so they can go home themselves. This had sometimes instead left us to walk the remainder of the way there through unpaved highway sidewalks.

After a few nights of it, I became more and more reluctant to continue because of the frenzy that it had almost every single night and it was extremely inconvenient for my time and the time of those with me. I didn't complete it then and I hadn't seriously tried until 9th Grade, which honestly was more uneventful.

That attempt was mostly my siblings and I staying in Makati City and Taguig City and going to easily traveled to churches that we could walk to by foot, and high-end malls that have annual Simbang Gabi masses for their shoppers, facilitated by the local diocese and the local fancy church. I was able to complete those easily because I was often dragged either by my siblings or my grandmother who used to never miss a day of church when she was still more active.

It was less about the challenge at that point and more of an obligation which isn't a bad thing and honestly is probably closer to how it should be celebrated.

I hadn't gone to Simbang Gabi since 2019 and I don't have any plans to try this year either. Not really because I don't want to necessarily, but specifically because I physically can't. I still think its pretty fun to do and honestly maybe a good excuse to meet with my friends that I haven't seen in a while. Sadly, I just simply cannot do it now nor in the near future.

Maybe one day I could once again go out at those cold December night to meet my friends and maybe eat some bibingka on my way home but I guess I'll just leave every one else to it.

Sources

Introduction

Advent. (n.d.). In Britannica. Retrieved on 13 December 2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Advent

In The Philippines Christmas Eve Includes A Late Night Street Food Feast, Filipino Christmas, HD wallpaper [image]. (n.d.). Peakpx. Retrieved on 15 December 2023, from https://www.peakpx.com/en/hd-wallpaper-desktop-wxdle

Petrelli, M. (2021, December 20). The country that celebrates Christmas for more than 4 months a year. CNBC. Retrieved on 13 December 2023, from https://www.cnbc.com/2021/12/21/philippines-the-longest-christmas-celebrations-in-the-world-.html

What is Simbang Gabi?

Álvarez, F. (2018, November 22). Una tradición matutina la Misa de Aguinaldo. Primera Hora. Retrieved on 13 December 2023, from https://www.primerahora.com/noticias/puerto-rico/notas/una-tradicion-matutina-la-misa-de-aguinaldo/

Hermoso, C. (2022, December 15). 9-day ‘Simbang Gabi’ begins on Dec. 16; anticipated masses to begin tonight. Manila Bulletin. Retrieved on 13 December 2023, from https://mb.com.ph/2022/12/15/9-day-simbang-gabi-begins-on-dec-16-anticipated-masses-to-begin-tonight/

Lazaro, J. (2020, December 11). The Christmas tradition of Simbang Gabi: After five centuries, this Filipino Christmas tradition lives on. U.S. Catholic. Retrieved on 13 December 2023, from https://uscatholic.org/articles/202012/the-christmas-tradition-of-simbang-gabi/

History

Hermoso, C. (2018, December 15). ‘Simbang Gabi’ a manifestation of the Filipinos’ strong faith in God, says bishop. Manila Bulletin. Retrieved on 13 December 2023, from https://mb.com.ph/2018/12/15/simbang-gabi-a-manifestation-of-the-filipinos-strong-faith-in-god-says-bishop/

Etheria (1919). The Pilgrimage of Etheria (McClure, M., & Feltoe, C. Ed. & Trans.). Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Retrieved on 13 December 2023, from https://www.ccel.org/m/mcclure/etheria/etheria.htm (Original work published 384 C.E.)

McClure, M., & Feltoe, C. (1919). [An image of the book cover of "The Pilgrimage of Etheria"]. Retrieved on 15 December 2023, from https://www.ccel.org/m/mcclure/etheria/etheria.htm

The Pillar. (2021, December 21). What time is Midnight Mass?. The Pillar. Retrieved on 15 December 2023, from https://www.pillarcatholic.com/p/what-time-is-midnight-mass

Misa del Gallo: origen, historia y por qué se celebra en la madrugada del 25 de diciembre. (2022, December 24). Marca. Retrieved on 15 December 2023, from https://www.marca.com/tiramillas/actualidad/2022/12/24/63a6c106268e3e7c468b45e8.html

Vintage Philippine Islands 1920-1959. (2020, December 25). A Vintage Greeting Card showing Philippine Christmas… Maligayang Pasko from Vintage Philippine Islands 1920-1959 [image]. Facebook. Retrieved 15 December 2023, from https://www.facebook.com/510513375695362/photos/a.1701322009947820/3595821097164559/?type=3

In the Present Day

Adarlo, S., & Pastor, C. (2014, November 3). Fr. Joseph Marabe breaks silence over Simbang Gabi ban (Part 2). The FilAm: A Magazine for Filipino Americans in New York. Retrieved on 15 December 2023, from https://thefilam.net/archives/16127

Balitang America, ABS-CBN North America Bureau. (2014, September 19). Simbang Gabi returns to NYC after a brief ban. ABS-CBN News. Retrieved on 15 December 2023 from https://news.abs-cbn.com/global-filipino/09/19/14/simbang-gabi-returns-nyc-after-brief-ban

FEU Memes. (2012, December 15). eto yung mga madalas ko makita sa gilid ng simbahan e [image]. Retrieved on 15 December 2023 from https://www.facebook.com/PIYUMEMES/photos/a.210778985704527/317211885061236/?type=3

Macaira, E. (2023, December 15). Simbang Gabi: It’s the mass, not the time. Philippine Star. Retrieved on 15 December 2023, from https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/12/15/2318980/simbang-gabi-its-mass-not-time

Malicdem, E. (n.d.) The Bamboo Organ Church or the St. Joseph Parish Church of Las Piñas City in the Philippines during "Simbang Gabi" or Night Mass on Christmas eve. Photo was part of Schadow1 Expeditions coverage of Las Piñas during Christmas season. [image]. Retrieved on 15 December 2023 from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simbang_Gabi#/media/File:Las_Pinas_Church_during_Simbang_Gabi.jpg

Punay, E. (2016, December 19). ‘Simbang Gabi’ won’t grant wishes – Bishop. Philippine Star Global. Retrieved on 15 December 2023, from https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2016/12/19/1654920/simbang-gabi-wont-grant-wishes-bishop

rhapido. (2022, November 30). Simbang gabi starter pack [Screenshot]. 9Gag. Retrieved 15 December 2023, from https://9gag.com/gag/a5Xnzgr

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

May mga tao tayong kailangang palayain para mapalaya rin ang ating mga sarili

May mga hangganan na kailangan natin tanggapin para maipagpatuloy ang ating lakbayin

May mga distansiyang kailangan nating panatiliin para masagip ang natitirang pag ibig

At may mga peklat na hindi kailangang lagyan ng takip para manatili ang aral na gustong ipabatid

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Painting a picture of the history of Filipino Tattoos

A photo of tattooed Filipino men posted on BBC and accredited to Joe Ash

Tattoos are often seen as integral cultural symbols in my different societies whether it be seen as something honorable or dishonorable. Even in the most straight-laced cultures, a tattoo acts as a mark of some form of the person's history and their standing in their communities as well as how people perceive them.

In a lot of modern cultures, the tattoo often have negative connotations, often associated with delinquency or criminal activity. Historically, however, they may have grander and more honorable significance in different societies. The communities that had existed in the Philippines prior to contact with Spain fits this similar pattern.

Before I start

As usual, the Philippines is a diverse country that has different traditions and histories that come from different ethnic groups and states, only being first unified under a government by colonization. Because of this, this post will only be able to cover parts of this culture and may not be able to fully encompass all Filipino traditions, practices, and beliefs about tattoos.

This is also given the fact that more specific information may be harder to come across or may not exist at all in a space I could easily access.

That being said, the general term for Filipino traditional (both precolonial and current) tattoo practices is batok, batik, patik, or patek depending on language or culture. It is also known as buri or burik in several other groups and languages. This word, however, isn't often used for typical tattooing in most modern communities.

The History

From a general understanding of a lot of precolonial Southeast Asian cultures, it can be assumed that precolonial Filipino societies heavily valued tattoos as their neighboring maritime SEAsian countries also had prior to the introduction of Abrahamic religions to the region which often discouraged or even forbade tattooing the skin.

Although this can be assumed, there were no known precolonial description nor record of these tattoos during the actual time period before Spanish contact. There is evidence found in some burial sites however, as discussed by social anthropologist Salvador-Amores in her paper The Recontextualization of Burik (Traditional Tattoos) of Kabayan Mummies in Benguet to Contemporary Practice (2012). In the paper, she focuses a section on the history of burik by explaining the Kabayan Mummies or the Fire Mummies of Benguet, Mountain Province.

An image of one of the Kabayan Mummies uploaded by Dario Piombino-Miscali on ResearchGate.net

These remains had been dated back to the 13th century and are associated with the Ibaloi, an indigenous ethnic group from Mountain Province found in the northern parts of the island of Luzon. This does confirm that tattooing had been important to the people who had lived in this area during this time period as, in Salvador-Amores's paper, it can be noted that the tattooed mummies seem to be prominent with the adults.

I do have to note that the Ibaloi people, who are part of the larger Igorot ethnic group, were not fully colonized by the Spaniards and therefore does not share the similar Hispanic culture and history that a lot of Filipino groups have. They had only fully been integrated into the Philippines during the American colonial period where they and the other Igorots had been properly colonized by American and placed under the rule of the American-controlled Filipino government. (x)

Regardless, this does show that at least some cultures in the archipelago held tattoos with high importance and did not consider them as something negative compared to the modern perception of tattoos.

The first known illustration of tattooed Filipinos, however, was first seen in the Boxer Codex (circa 1590) during the early Spanish colonial period, written and illustrated by an unknown author.

A page from the Boxer Codex (circa 1590), author uknown

This illustration seems to be that of the specific ethnolinguistic group, the Visayans as this page is next to another one labeled as "Biſſaya", a likely earlier spelling of Bisaya that uses the long s (ſ). This aligns with the description given as early as Antonio Pigaffatta, Ferdinand Magellan's chronicler, who consistently describes the Visayans that he has met as painted in his account of their arrival in the islands back in 1521.

The book The Philippine Islands 1493-1898 Vol. XII has compiled different first-hand and second-hand sources about the Philippines during the 15th through 19th century, with Vol. XII focusing on the early 17th century which aligns closely to the Boxer Codex. Within the text, there are several mentions of the "Pintados" or the Painted ones, even having an entire province be called the "province of Pintados".

It isn't made clear who the Pintados are besides the fact that they seem to be hostile towards the Spanish colonizers and had often fought battles with one of the letters even claiming that they had poisoned one of the Spaniards. It isn't until we reach the last part of the compilation which features Pedro Chirino's Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas which I had a hard time finding before but had now found a free and accessible copy. Within Chirino's writing, he explains that the Pintados seem to be a name given by the Spaniards to the Bisayans and further explains it as such:

"The people of the Bisayas are called the Pintados, because they are actually adorned with pictures --not because this is natural to them, although they are well built, of pleasing countenance, and white; but because they adorn their bodies with figures from head to foot, when they are young and have sufficient strength and energy to suffer the torment of the tattooing; and formerly they tattooed themselves when they had performed some act of valor."

Chirino even gives an explanation as to how precolonial Visayans tattooed their skin:

They tattoo themselves by pricking the skin until the blood comes, with sharp, delicate points, according to designs and lines which are first drawn by those who practice this art; and upon this freshly-bleeding surface they apply a black powder, which is never effaced. They do not tattoo the body all at the same time, but by degrees, so that the process often lasts a long time; in ancient times, for each part which was to be tattooed the person must perform some new act of bravery or valiant deed

It is notable, however, that not only did the Spanish not mention any tattoos on other Filipino groups such as the Tagalogs, but a lot of the illustrations in the Boxer Codex do not sport any tattoos at all which makes it confusing as to when had tattoos faded out of cultural significance in these other communities, likely even before Spanish contact.

Lane Wilcken, a researcher who studies the history of tattoos from the Philippines and the Pacific Islands, writes in his book Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern (2010) that it may be possible that the Tagalogs may had lost their tattooing traditions shortly before Spanish contact during the recent islamization of their communities circa 1500 which was and specifically in the polity of Maynila. This may also be the case for the Moros which is a muslim ethnolinguistic group found in the island of Mindanao.

Either way. tattoos became more scarce within Filipino records after the arrival of the Spanish and the introduction of Christianity to the islands, save for some indigenous groups that were not fully colonized by Span like previously mentioned Igorot people.

Because of the spread and dominance of Christian and Islamic customs throughout the country, Batok, as it originally was, was lost to time with the lack of existing artists and cultural relevance tattoos. Tattoos didn't come back to the Filipino mainstream until modern tattoos became more prevalent especially in the mid to late 20th century, similar to its rise in popularity in Western cultures, and even then, it wasn't really what I would consider any traditional and is often negative.

Present Day

Like a lot of other countries, however, tattoos had seen a swing of opinion and is more accepted now as an art form rather than a sign of criminal activity but some stereotypes are still popular.

For instance, during the COVID-19 lockdown, the Department of Education provided modules for students to answer at home which would be then collected by the school from door to door. In one of these modules, Lea Salonga, a Filipino singer, complained on November 17, 2020 on her Facebook page of a discriminatory question that was found in one of the modules, pictured below

EN Translation:

White text: The answer is letter A based on the DepEd answer key.

Module text:

3. Tattoos are a symbol of _____

A. being a criminal

B. being a slave

C. courage and beauty

D. having a low standing in society

This controversy caused an uproar online and showed that there are a lot of Filipinos today that don't see a problem with tattoos and even see them as a positive. Two days after the image was posted on Salonga's page, the Department of Education publicly recognized the misstep and had issued that they officially recognized the controversial answer as an error.

It is important for me to note that, just like in a lot of countries, tattoos are typically not accepted in the corporate world and those who have them either have to get them removed or at least cover them up if they get hired at all. There's still a common idea that people with tattoos, if not dangerous, may be seen as unprofessional or even unclean which I do know is a similar thing that other countries may have as well.

As for batok, its comeback in the larger Filipino mainstream didn't return until some time in the late 2000s and 2010s when more international influence had resparked and interest in more ethnic cultures including the precolonial Filipino tattoos specifically because of the internet and the rise of social media. The current batok that we see outside of indigenous communities could be seen as a recreation of the extinct practices within the Philippines with some level of appropriation from related cultures (by appropriation, I mean this in a neutral way not a negative one).

It is argued whether or not the reconstructed practice could be considered traditional at all, but considering its heavy emphasis on the older designs found in historical illustrations as well as designs from indigenous communities that did not have practice eradicated by colonization, some also argue that the modern tattoos that has gained prominence because of modern technology and research is still valuable in a socio-anthropological sense.

As Salvado-Amore puts it

the successive phases and changes in the status of burik tattoos—enabled by the advent of modern technology, the Internet, and mass media—encourage an interaction between contemporary and historical influences rather than an extinction of past practice.

About Apo Whang-Od

A magazine cover of Vogue featuring Whang-Od, a traditional tattoo artist from the Butbut people, a subgroup within the Kalinga ethnic group. (The rest of this section pulls from the same article by Vogue)

Any research about Filipino tattoos, especially in the modern day would be incomplete without any mention of Whang-Od, the most popular traditional tattoo artist from the Philippines.

Apo Whang-Od (b. February 17, 1917, a.k.a. Maria Oggay) is a member of the Butbut people of the Kalinga indigenous ethnic group from Kalinga province, Philippines. She is often known as one of the last mambabatok in the country which earned her fame and recognition internationally. She started her tattooing practice since she was a teenager at age 16, under the mentorship of her father and was the only known female mambabatok during her time.

For years, she was called on by different communities within her locale in order to tattoo important and symbolic tattoos on members of her and different communities after they had received certain milestones. Men were tattooed for different reasons than women as men were given their marks when they succeed in activities like headhunting, which was ritualistically important for the Butbut people while women were tattooed for reasons like fertility or beauty.

Because of American colonization, however, headhunting was prohibited so she was mostly tattooing women from then onward.

She started gaining recognition some time in the mid-2000s to the 2010s after she started serving foreign tourists, although she doesn't give them the more traditional symbols. Non-members of the group are given a set of tattoos that she could tattoo on anyone without any strong connection to the original meaning of the art.

Since tattooing was passed through family and Whang-Od herself didn't had any children, she was known as the last mambabatok for a time which caused concern for the extinction of the practice as she was already in her 90s when she gained notoriety, but she has since started training her grandniece Grace Palicas and later on her other grandniece Elyang Wigan and the two, who are now in their 20s, has since helped their great aunt dealing with their clientele.

Due to her fame, she is often the subject of foreign media and interest, even being invited by Vogue magazine to pose for one of their covers (pictured above) and is now known as the oldest Vogue cover model earlier this year at the age of 106.

Despite her fame and arguably cultural importance to not only the Kalinga people but the Philippines as well as online petitions since the 2010s to give her the recognition, she is not eligible to receive the National Artist award— one of the highest awards given to artists of most artistic fields of which only 81 people had received. Victorino Manalo, Chairman of the National Commission for Culture and Arts (NCCA) explains that this is because her craft, tattooing, isn't covered by the NCCA but by the Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan (GAMBA, en. Award for Crafters/Creatives of the Nation) but there has been some discussion within the commission about this issue which still ended with her being denied. In light of this, she is now currently on the running to possibly receive the GAMBA award.

She has an online presence managed by others and she can be found via Facebook and Instagram.

Tattoos now, from my experience

As I had said before, tattoos these days are not as negatively seen as they were in the 20th century and had received a more positive reputation thanks to the rise of its social experience due to the internet and social media's prevalence in the country. As an art student, in fact, it's wasn't that surprising when I learned that one of my classmates had a tattoo and it was even a full sleeve! Now, as least three had tattoos before they graduated with one of them actually being a close friend of mine who's planning to get more despite their parents' disapproval.

Despite this, I still do have people in my life right now that see tattoos as undesirable and unclean, with stereotypes still being prevalent. I had once heard people speak of them in such a negative way but then make an exception for the artsy type of people? It's odd.

As for batok or batik, I had not seen a lot of people with these tattoos in my own life and had only seen it through articles and images circulated around by other people who I don't even know. I guess it makes sense as most people who do get tattoos similar to batok or batik often do it in tourist-y places or are foreigners who want to get a piece of Filipino culture on their way out of the country.

Besides more culture-focused people, batik or batok isn't as prevalent as some of these articles might make it seem and most typical Filipinos who don't come from these cultures are more likely to either not have tattoos at all or have similar tattoos to those that you may see in other countries.

Either way, tattoos could be so personal to a person and whether it's something as deeply-rooted to culture like batik or if it's just the names of your favorite K-Pop idol, that tattoo is important and has special meaning. Get whatever tattoo that you want or don't if you don't want any at all!

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Time Factor

The intermediate tape-worm of time unreels

Unwinds and stops dead.

The secret here is that this garden’s spell

Is for all time, the magic spilling over

From the grip of the dark abysm.

Here are impressed crannied deep

More than the eyes avow;

Carved telltales to bemuse the wary,

Jaded, and unseeing. It is thus, not any

Absence here nor time’s toll

But love’s bafflement, impaled,

No brave hands may set free.

Perhaps, in another moon or bloom

This play for feeling could well have been

Mere obeisance to some monarch’s lust,

A prodigous lush screening such

Stealthy crevices, swelling into the

Dark incandescence of bodies, for

Right here and now, your impetous blaze,

Announces: love will, for the proper

Reason, for whatever reason,

Even as strong as flashflood signs warn

The face is wrong in this confused season,

You and I meet, at the wrong time,

Giants both standing above time,

Playing for time, loving against time,

Time living at the midpoint

And the crux of timelessness.

You could have been Wu Ti

Scrounging from the plums

And berries of riper order

Or his simpling sibling, and I,

Strangely, of one silla’s starry-bosomed-

Maidens, sybillize, dancing to a

Different time in a warmer clime,

Recreacting an ethos more ancient than

Your cry: I want you in anywhere or

Way or how, now or in another time:

Your voice thrusts the message in,

In this cold age, while the arms

Seek warmth in another face

In a gesture, not yours,

But which could have been were years,

To shuttle to and forward, forth

Floating towards time , towards this suspended

Moment in no imagined space.

Two age-wrenched passions meet, miss

Time’s cues, mistake time’s script,

And if time were out today, who cares?

Nevermind the lapse in history

And in place. Out there may well

Be right here and in the heart of Seoul.

In this soul, in the heart of this

Garden secret to all else, set against

The mose luminous of skies, proclaiming

This is perfect, only You and I

Suddenly meeting and for no reason

Except the most holding; it is not right?

We meet, want, limn in each other’s

Fictive flesh an allegory of our kind

Of love, conceived and born in this garden

From the past, and of this single moment,

And for the many more centuries to come.

(Ophelia Alcantara-Dimalanta)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Two age-wrenched passions meet, miss Time’s cues, mistake time’s script, And if time were but today, who cares? Never mind the lapse in history And place.”

—

Ophelia Alcantara-Dimalanta (The Time Factor)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

You cry: I want you in any where or

Way or how, now or in another time:

Ophelia Alcantara Dimalanta, from "The Time Factor" in One Hundred Love Poems: Philippine Love Poetry Since 1905

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read Me - Ophelia Dimalanta

whenever my voice flings arrows

your way at a fiery pace,

read, discover there is that

something in me that dies to go gentle.

for when i viciously tangle

with you trying to throw

you off course, inside, i am raring

to cover you, take you, become

all of me fire and fluid.

when i try to lord it over, empowered,

it is because inside i am already

slave groveling ready to heed your bidding,

crawling waves lapping you up

sea shore hillocks sky

all the way up, all drool and drivel.

and when i insolently seek out

pulpits to mount my gospel truths,

i am really one humped question mark

thrashing about for your steadying light.

and when i try to light you up whole,

there is really a part of your flame

i would want extinguished

to die rekindled in me alone,

and when i am wind taking roots

in your solid ground, i am roots as well

ready to take flight upon your wings.

when i prance around proud in times square.

i am child carousing in the greener

fringes of the heart’s final roosting.

read this idiolect,

read well, decode, detect,

and love me when i seem to hate.

–Ophelia Dimalanta

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Kind of Burning

it is perhaps because

one way or the other

we keep this distance

closeness will tug us apart

in many directions

in absolute din

how we love the same

trivial pursuits and

insignificant gewgaws

spoken or inert

claw at the same straws

pore over the same jigsaws

trying to make heads or tails

you take the edges

i take the center

keeping fancy guard

loving beyond what is there

you sling at the stars

i bedeck the weeds

straining in song or

profanities towards some

fabled meeting apart

from what dreams read

and suns dismantle

we have been all the hapless

lovers in this wayward world

in almost all kinds of ways

except we never really meet

but for this kind of burning.

– Ophelia Dimalanta

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ilokano yung nanay ko pero di ako marunong mag-Ilokano kasi tinigil niya pag-Ilokano sakin nung bata pa ako. Sayang naman kasi maka-Ilocos lang ang karamihan ng pamilya ko dun sa Ilocos. Parang nakalimutan ko rin ang heritage ko in addition to sarili kong wika.

Andaming pinoy sa UK na marunong lang mag-Ingles at dahil dun, hinayang na hinayang sila. Feeling sila “white washed” daw.

Translation: my mother is from Ilocos but I don’t know Ilokano because she stopped speaking Ilokano to me when I was a kid. It’s a shame because most of my family only know Ilokano. It’s as if I forgot my heritage too in addition to my mother tongue.

Many Filipinos in the U.K. only know English and because of that, they really regret (it). They (say they) feel whitewashed.

For the love of god if your native language is different from the majority language of the country you’re living in don’t raise your baby speaking the local language. Either have each parent speak to them in a different language or only speak your native language at home. The kid will be okay. Get your native language in their head. You may think you’re helping them in the long term giving them the local language but no. When they’re an adult they’ll wonder why you never taught them your language. They can and will learn the local language in school. They’ll be okay. Produce more bilingual children. They are good for society.

28K notes

·

View notes