#Anchiornithid

Text

In a dense Sequoia forest where the darkness is broken by only a single solarbeam, a Caihong curiously inspects a Kalligrammatid, seeing a face not unlike its own staring back from the strange insect's transparent wings.

A bit of an experimental piece. Although kalligrammatids superficially look like butterflies, these Jurassic insects are in fact lacewings, entirely unrelated to butterflies! One of the differences this implies is that their gorgeously patterned wings were in fact transparent. This gave me the idea to use some extreme backlighting to really show them off, as well as the gloriously iridescent Caihong's feathers. This watercolour, for which I gratefully used this fantastic guide to restoring Kalligrammatids, features Affinigramma myrioneura; Kallihemerobius almacellus, aciedentatus, and feroculus; Kalligramma circularia, and the Maniraptoran-mimic Kalligramma brachyrhyncha.

#caihong#anchiornithid#kalligrammatid#neuroptera#avialan#bird#theropod#dinosaur#insect#cw: bugs#backlighting#watercolour#dark#jurassic#paleoart#my art#palaeoblr

147 notes

·

View notes

Note

Trick or treat!

Anchiornis!

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Archovember Day 1 - Your Choice!

In my ongoing effort to draw all the non-avian dinosaurs we know the colors of, I’ve chosen Anchiornis huxleyi!

The type species for the Anchiornithids (“near birds”), Anchiornis huxleyi was a crow-sized dinosaur living in the Late Jurassic of Liaoning, China. It was relatively common, as hundreds of specimens have been uncovered in this area. But what makes Anchiornis so unique and important is that it was the first Mesozoic dinosaur species to have its entire life appearance be known by man! Having hundreds of well-preserved fossils available allows us to extract a lot of information about not only its size and shape, but its skin, feathers, and even coloration. Anchiornis had long wing feathers on its arms and legs (though its leg feathers were not as long as those of Microraptorians), fluffy downy feathers all over its body, a feathered crest on its head, and feathers covering its feet.

Only two Anchiornis fossils have had their well-preserved melanosomes studied so far. By comparing the structure of these melanosomes to modern birds, paleontologists have been able to infer the life colors of Anchiornis! It had mostly gray and black body feathers and white forewing and hindwing feathers with black tips. Its tail colors remain unknown. The first specimen of Anchiornis to be surveyed for melanosomes also had red or rufous coloring on its crest, as well as rufous speckles on its otherwise black and gray head. However, the second specimen did not have any rufous coloration. This may be due to different preservation of melanosomes, different investigative techniques, the animals in question having regional differences or even being different species/subspecies, the second Anchiornis being younger, or sexual dimorphism.

While Anchiornis had rather large feathered forelimbs, it didn’t seem to have been much of a flier. Unlike the later Microraptorians, its wings were rounded and relatively short compared to other flying dinosaurs, and the flimsy flight feathers overlapped each other to strengthen them. A 2016 study concluded that while juvenile Anchiornis may have been able to use their wings to assist with leaping through the trees, adults were simply too heavy and their wings too small to gain any lift. Instead, it is more likely their wings were used for display. As their legs were long, they may have been adapted for speed, using their wings to aid in aerodynamics as they quickly darted through the underbrush.

Pellets (such as those coughed up by owls) have been found both within and in association with Anchiornis, and contained lizard bones and fish scales. Prey items that could have also been eaten by Anchiornis include insects, arachnids, salamanders, small anurognathids (such as Cascocauda, who we will be visiting later this month) and other small or juvenile pterosaurs, and small cynodonts like Agilodocodon and Juramaia.

Anchiornis lived alongside other Anchiornithids such as Aurornis, Caihong, Eosinopteryx, Pedopenna, Serikornis, Xiaotingia, as well as the Scansoriopterygids Yi, Scansoriopteryx, and Epidexipteryx. It also lived alongside the quilled heterodontosaurid Tianyulong.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Anchiornis huxleyi#Anchiornis#Anchiornithid#paravian#theropods#saurischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#Archovember#Archovember2023

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

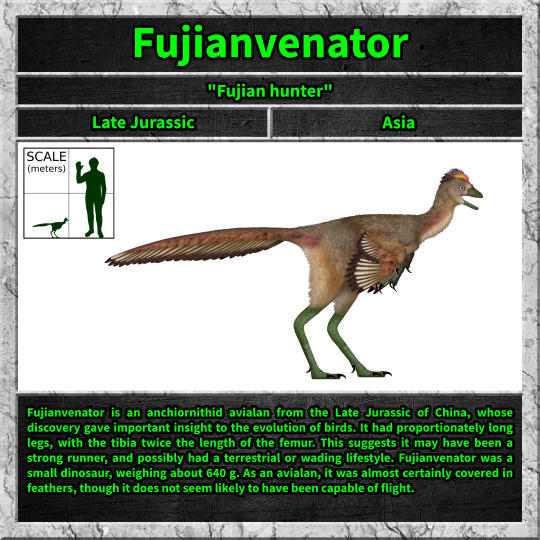

Fujianvenator

Fujianvenator is an anchiornithid avialan from the Late Jurassic of China, whose discovery gave important insight to the evolution of birds. It had proportionately long legs, with the tibia twice the length of the femur. This suggests it may have been a strong runner, and possibly had a terrestrial or wading lifestyle. Fujianvenator was a small dinosaur, weighing about 640 g. As an avialan, it was almost certainly covered in feathers, though it does not seem likely to have been capable of flight.

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

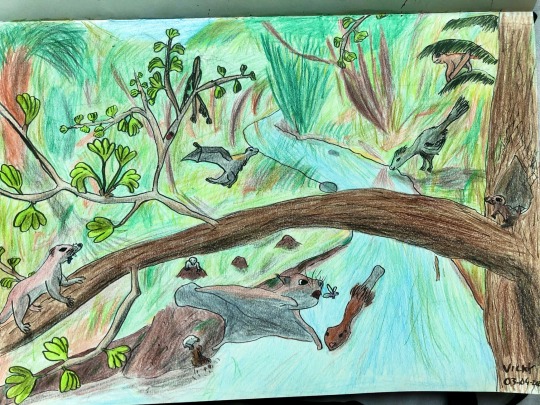

Here’s some of the amazing diversity of Mammaliaformes of Jurassic China. Volaticotherium glides in pursuit of a tasty bug. Agilodocodon, an excellent climber, already got one and brings it back to its young in the trees. Some Docofossors are digging up the lawn. Castorocauda, the largest mammaliaform of the Mesozoic, is going for a swim. With the exception of Volaticotherium, these are all Docodonts, a group closely related to the crown group mammals, having branched off a little before the monotremes did. I wanted to show off how much more diverse and interesting Mesozoic mammals were than we usually imagine. They did a lot more than cowering from dinosaurs and being eaten by them!

That said, Jurassic China also had some really cool dinosaurs.Yi qi, the actual real-life dragon, is going for a flight. A truly enormous Xiaotingia is having a drink. Please mentally halve the size of that big boy, I accidentally drew it way too large, that is a little birdie that should be easily outsized by Castorocauda. Finally, being neither a dinosaur nor a mammal, the not at all confusingly named pterosaur Cascocauda is sitting in the trees getting ready for a flight.

#mammaliaform#volaticotherium#castorocauda#docodonta#agilodocodon#docofossor#eutriconodonta#yi#yi qi#scanseriopterygid#xiaotingia#avialan#anchiornithid#cascocauda#pterosaur#anurognathid#mesozoic mammals#jurassic#paleoart#palaeoart#my art#i'm seriously kind of annoyed with how big i made xiaotingia#it feels like it's stealing the thunder of the mammals#especially castorocauda#i'm too used to drawing dromaeosaurs#anchiornithids are teeny tiny compared to them#dinosaur#mammal

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

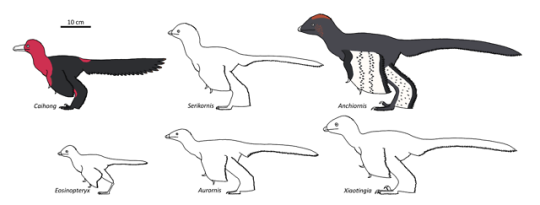

What did the last common ancestor of Velociraptor and modern birds look like? Anchiornithids might give us a clue. These small dinosaurs lived 160 million years ago and are known from incredible fossils, often complete with skin and feathers.

Full view

#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Dinosaurs#Birds#Anchiornis#Xiaotingia#Caihong#Serikornis#Aurornis#Eosinopteryx#Anchiornithids

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 28 on #jurassicjanuary is “underneath” and this time, a basal Avialae (anchiornithid) Serikornis is searching a small insect or reptile that is underneath the log.

#Jurassic January#middle jurassic#jurassic#serikornis#paraves#anchiornithids#avialae#my art#paleoart#paleoblr

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caihong juji, a spry little anchiornithid from the Jurassic of China. While not a true bird, it was probably pretty close on the evolutionary line to them, as evidenced by it birdlike build and well-feathered arms.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shakrok Biology- Introduction

Shakrok are large, sophont anchiornithids. (the most primitive type of bird) They are analogous to humans in many ways, making tools, using language, and are of equal intelligence to humans.

The average Shakrok is about 120 cm, or 4 ft at the withers, and about 340 cm, or 11 feet long, from the tip of the beak to the tip of the tail, following the spine.

The feathers on the the fingered arms are reduced, in order for greater touch, traction, and movement. The claws on the fingers are short and blunt. The head is teardrop.

Males are slightly taller and lankier, have more reddish plumage, have brighter eyes, and have a reddish snout. Female are shorter and stockier, have more brown plumage, and have brown snouts.

The eggs are large, nearly circular, and white. Incubation typically takes about 6.5 months, and the eggs are about 30 cm, or 1 foot in length. When hatched, the babies are premature compared to human babies, and are fed regurgitated food. Both sexes are capable of this, and regurgitation is also used in courtship and to enforce romantic bonds. At about 5 years of age, they have lost all of their down and are covered in complex plumage. By about 10 years of age, they are adolescent and start to go through puberty. By around 20, they are physically, and almost mentally mature.

an example of a real anchiornithid if u want a good idea of what they look like- https://twitter.com/SerpenIllus/status/933016844126081026/photo/1

1 note

·

View note

Text

Early avian evolution: The Archaeopteryx that wasn‘t

Paleontologists have corrected a case of misinterpretation: The first fossil "Archaeopteryx" to be discovered is actually a predatory dinosaur belonging to the anchiornithid family, which was previously known only from finds made in China.

Latest Science News -- ScienceDaily https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/12/171204150650.htm

0 notes

Note

Trick or treat!! 🦢

Xiaotingia!

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

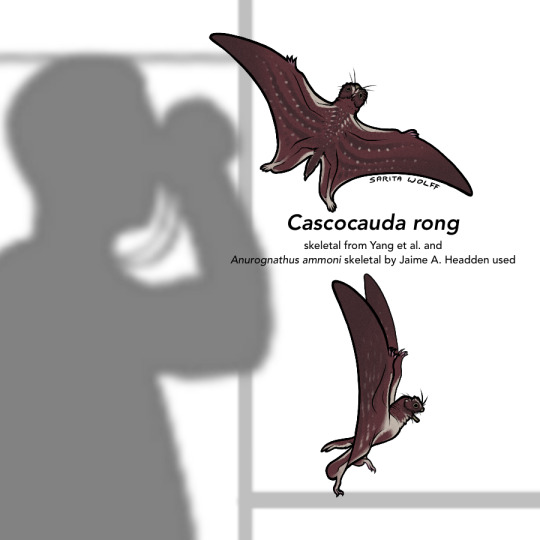

#Archovember Day 18 - Cascocauda rong

The Anurognathids of the Jurassic and Cretaceous were highly derived pterosaurs that filled a similar niche to bats. They were nocturnal or crepuscular, insectivorous (though some larger species may have eaten fish as well), arboreal, and had short tails. However, Cascocauda rong of Middle - Late Jurassic China was an exception to the short tail rule. It’s tail was longer than other known anurognathids, earning it a name meaning “fluffy ancient tail.” But more importantly, Cascocauda provides us evidence of the complexity of pycnofibers in pterosaurs. Long thought to be simple and furlike, pterosaur pycnofibers were thought to be unique structures that evolved independently from feathers. However, Cascocauda had an array of different pycnofiber shapes and structures, one of them being similar to downy feathers with frayed ends. This further strengthens the hypothesis that feathers evolved before dinosaurs and pterosaurs even split into two different clades. Also, infrared spectral analysis was used on these pycnofibers, showing they had a similar absorption spectra to red human hair, making Cascocauda one of the only pterosaurs for which we know its coloration!

Found in the Tiaojishan Formation, Cascocauda rong would have lived with other anurognathids like Jeholopterus, Sinomacrops, and the tiny Luopterus. A wealth of other types of pterosaurs existed here as well, such as Darwinopterus, Kunpengopterus, Archaeoistiodactylus, Pterorhynchus, Wukongopterus, Daohugoupterus, Douzhanopterus, Fenghuangopterus, Jianchangnathus, Jianchangopterus, Qinglongopterus, and Liaodactylus. Dinosaurs lived here too, including the famously colored Anchiornis and other Anchiornithids like Aurornis, Caihong, Eosinopteryx, Pedopenna, Serikornis, and Xiaotingia, as well as the bizarrely bat-winged Scansoriopterygids Epidexipteryx, Scansoriopteryx, and Yi, and the quilled heterodontosaur Tianyulong. Arboreal cynodonts like Agilodocodon, Juramaia, Maiopatagium, Arboroharamiya, Volaticotherium, Vilevolodon, and Xianshou would have shared the trees with Cascocauda rong, adding to the busy, fluffy, feathery nature of this ancient forest.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Cascocauda rong#Cascocauda#anurognathids#pterosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is flashiest tailed birb group??? vote now on phones!!!

#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#poll#raptors#birds#I know dromaeosaurs will probably win but I can dream and hope right?#chickenparrots#anzu#velociraptor#stenonychosaurus#anchiornis#archaeopteryx#confuciusornis#yi

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you suspect that Microraptorines and Anchiornis had trouble walking due to their legwings? (Before you ask: domestic pigeons with extensive legwings (such as the Silesian Swallow) do have worse movement than ordinary pigeons, in case it’s relevant))

I’ve asked Katrina van Grouw (whose husband is an experienced pigeon breeder) about whether foot feathers impede terrestrial locomotion in pigeons, and her response was “not really”. Granted, that’s a fairly generic answer that could mean anything from “it does not impede them at all” to “it does slightly inconvenience them, but doesn’t prevent them from engaging in terrestrial activities”. Watching videos of pigeons with extensive hindlimb feathers myself, they do look somewhat clumsier on the ground compared to pigeons without foot feathers, so I suspect the latter end of the spectrum applies here. However, I would caution against extrapolating similar locomotory capabilities to microraptorians and anchiornithids for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, given that extensive foot feathers can be bred into pigeons in only a couple of generations, and the resulting birds usually receive care from humans, it’s probable that domestic pigeons with feathered feet haven’t been selected for potential behavioral adaptations that might minimize the negative effects of this trait, such as postures that reduce contact of the feathers with the ground (e.g.: standing with the ankle joint highly extended, as suggested by Dececchi and Larsson, 2011) and increased preening of the hindlimb feathers. The same cannot be assumed for Mesozoic paravians.

Secondly, to my eye at least, much of the clumsiness in feather-footed pigeons appears to stem from the fact that they have large feathers sprouting not only from their tarsometatarsus, but from their toes as well. Whereas the tarsometatarsal feathers could conceivably be raised off the ground during walking, the feathers on the toes inevitably drag along. In Mesozoic paravians with well-preserved hindlimb feathers, the larger feathers appear to be limited to the metatarsals on up, as seemingly shown by Changyuraptor and several specimens of Microraptor. Anchiornis is known to have had feathers on the toes, but these were much shorter than the metatarsal feathers. One video I’ve seen of a feather-footed pigeon appears to show it living feral with very worn feathers on the toes, whereas its tarsometatarsal feathers remain relatively pristine. That’s not a coincidence, I suspect.

My verdict then is that it’s possible that microraptorians and anchiornithids were less adept at walking than they would be if they didn’t have large hindlimb feathers. However, given that domestic birds with long feathers on the toes are only somewhat inconvenienced, and the Mesozoic paravians both appear to have lacked these long toe feathers and had the opportunity to evolve potential behavioral adaptations to compensate, I suspect that they probably weren’t as handicapped as often assumed.

This is certainly a subject that I’d like to see some more rigorous study on though. An experiment quantitatively measuring the effects of different degrees of hindlimb feathering on terrestrial locomotion in domestic birds (which could perhaps then be used to inform digital simulations of extinct dinosaurs with hindlimb feathers) would make a really good graduate project!

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I don't know who needs to see anchiornithid Fluttershy today, but you're getting anchiornithid Fluttershy.

79 notes

·

View notes