#Appellee

Text

12 Legal Terms - U.S COURTS

can you describe what these mean without googling? (You know cell phones aren't allowed in court..) =)

Article III judge

Automatic stay

Acquittal

Answer

Appellee

Appellate

false imprisonment

Admissible

Amicus curiae

Hearsay

Exclusionary rule

Settlement

#Article III judge#Automatic stay#Acquittal#Answer#Appellee#Appellate#false imprisonment#Admissible#Amicus curiae#Hearsay#Exclusionary rule#Settlement

0 notes

Text

« Trump’s claim of total executive immunity isn’t just unconstitutional; it is anti-constitutional and incompatible with the rule of law. A president with that kind of power is no longer a president but a king. »

— Jamelle Bouie at the New York Times.

The Supreme Court seems skeptical of Colorado's attempt to keep Turmp off the ballot based on 14th Amendment proscriptions on insurrectionists. Even the liberal justices see a problem with individual states acting to derail a national election.

However, the case related to Trump's immunity from all prosecution is a different matter. If a president was not obliged to follow the law, that would subvert the Supreme Court's own authority. Even Trump-appointed justices might think twice about diluting their own power.

The safest action by SCOTUS, and a good one for the rule of law, would be for the justices not to rule on the case themselves and implicitly let the judgement by the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit stand. The lower court's decision won praise from legal scholars and it would be difficult for SCOTUS to improve on it.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, APPELLEE

v.

DONALD J. TRUMP, APPELLANT

No. 23-3228

#donald trump#presidential immunity#scotus#us supreme court#constitutional law#us court of appeals for the district of columbia circuit#jamelle bouie#election 2024

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Further TL;DR rant on Eli Vanto

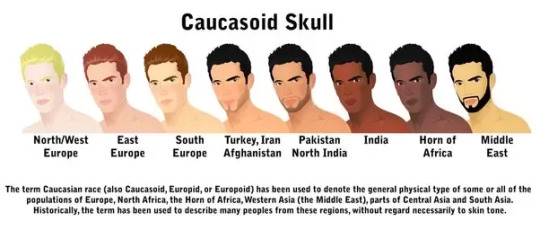

"Caucasian features."

It's been bugging the absolute f*ck out of me.

Yes, I am back on my Eli Vanto bullshit.

Break it down.

White America is a Color

First, I think that only in America is the word Caucasian used to mean white people. The American understanding of Caucasian as meaning white, European-descended people was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1923. The case of United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind ruled that under the Naturalization Act of 1906 that only "free white persons" - also called Caucasians - and "aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent" to become naturalized citizens. Bhagat Singh Thind's argument rested on the descent of Europeans and Indians from a common Proto-Indo-European origin. The court disagreed.

Excerpt below, full text here.

What we now hold is that the words "free white persons" are words of common speech, to be interpreted in accordance with the understanding of the common man, synonymous with the word "Caucasian" only as that word is popularly understood. As so understood and used, whatever may be the speculations of the ethnologist, it does not include the body of people to whom the appellee belongs. It is a matter of familiar observation and knowledge that the physical group characteristics of the Hindus render them readily distinguishable from the various groups of persons in this country commonly recognized as white. The children of English, French, German, Italian, Scandinavian, and other European parentage quickly merge into the mass of our population and lose the distinctive hallmarks of their European origin. On the other hand, it cannot be doubted that the children born in this country of Hindu parents would retain indefinitely the clear evidence of their ancestry. It is very far from our thought to suggest the slightest question of racial superiority or inferiority. What we suggest is merely racial difference, and it is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognize it and reject the thought of assimilation.

It is not without significance in this connection that Congress, by the Act of February 5, 1917, 39 Stat. 874, c. 29, § 3, has now excluded from admission into this country all natives of Asia within designated limits of latitude and longitude, including the whole of India. This not only constitutes conclusive evidence of the congressional attitude of opposition to Asiatic immigration generally, but is persuasive of a similar attitude toward Asiatic naturalization as well, since it is not likely that Congress would be willing to accept as citizens a class of persons whom it rejects as immigrants.

So, in America, the term Caucasian means 'white people' and not people of the Caucasus, or a group of people who have 'Caucasian features.' This is still accepted and common usage, despite the science of race being on a par with the sciences of alchemy, astrology, phrenology, a flat earth and the sun orbiting it.

Who with the What, Now?

A German philosopher named Christoph Meiners started the whole shitshow. He divided the races into the 'Caucasian' or 'beautiful' race and the 'Mongoloid' or 'ugly' race. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach carried it further in 1795, dividing humanity into five races by skin color.

First, this image is all over the search results, no findable attribution, but I'm using it because it's accurate in terms of skin colors:

Other 'Caucasian features' included narrow noses with small nostrils and a sharp nasal sill, small mouths with thin lips, prominent supraorbital (above the eye socket) ridges, orthognathism and high cheekbones. Of course, in the late 1700s when all this was being quantified into 'racial features' not many Caucasoids fit into the categories. Not a lot of people do today. I'd love to have everyone in America take a 23-and-Me test, then make them sit down, shut the fuck up and think.

Star Wars and Mis-coloring

I am old enough to remember when Lando Calrissian was the only black man in the galaxy.

Eli Vanto.

Tan.

Really.

The definition of 'tan' is a yellowish brown color, or the processing of leather, but we're going with the classic "brown or darkened shade of skin developed after exposure to the sun." In short a tan is acquired and not an innate skin color. It doesn't help that one of the most referenced fandom resources repeatedly characterizes brown people as 'tan.'

Even Breha Organa is miscolored as 'golden tan.' These guys did not acquire a goddamn tan hanging out on Scarif. Luke Skywalker was mighty white even after living his whole life on a desert planet, and Obi Wan had not a trace of tan despite living there as long as Luke. These are brown people. Black characters such as Adi Gallia and Mace Windu are characterized as "dark."

For shit's sake. Is everyone at Wookiepedia afraid of the word 'brown?'

Light brown. Medium brown. Dark brown.

I realize that the GFFA doesn't have Earth's definitions of ethnicity, nationality, or race but miscoloring is miscoloring. Tacking on 'Caucasian features' is adding a racist trope to insult. Structural racism in the US is deeply ingrained and often the default setting when it comes to media. It is important to give people their representation when it is right fucking there.

Eli Vanto is brown. His canon appearance is in the comics, and while he might have been originally storyboarded as a white redhead, he did not stay that way. His voice actor in the audiobooks gave him a Texas twang, but maybe in other versions of the audiobook, he speaks with a different accent.

Turkish Eli? Sure.

Brazilian Eli? Absolutely.

Oaxacan Eli? Why not.

Desi Eli? Heck yes.

Mizrahi Eli? Bring it.

He's brown. Not white. Not tan with Caucasian features. He is as brown as Thrawn is blue.

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

Johnny Depp’s Appeal’s brief.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

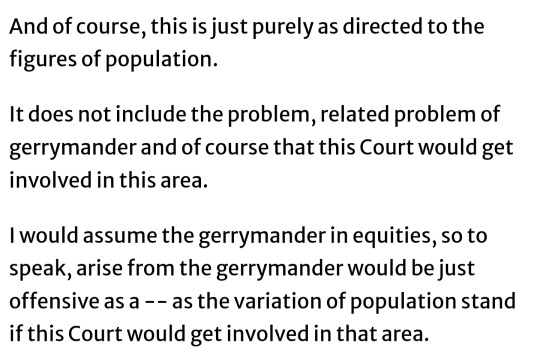

Oral Argument at 1:32:57, Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964) (No. 63-22) (Assistant Attorney General of Georgia, for the appellees, November 18, 1963).

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Art. 1164 of the New Civil Code

The creditor has a right to the fruits of the thing from the time the obligation to deliver it arises. However, he shall acquire no real right over it until the same has been delivered to him.

Sample Case:

A. A. ADDISON, plaintiff-appellant vs. MARCIANA FELIX and BALBINO TIOCO, defendants-appellees

G. R. No. L-12342, August 3, 1918

FACTS:

By a public instrument dated June 11, 1914, the plaintiff sold to the defendant Marciana Felix, with the consent of her husband, the defendant Balbino Tioco, four parcels of land, described in the instrument. The defendant Felix paid, at the time of the execution of the deed, the sum of Php 3,000 on account of the purchase price, and bound herself to pay the remainder in installments.

In January 1915, the vendor, A. A. Addison, filed suit in Court of First Instance of Manila to compel Marciana Felix to make payment of the first installment of Php 2,000. The defendant, jointly with her husband, answered the complaint and alleged by way of special defense that the plaintiff had absolutely failed to deliver to the defendant the lands that were the subject matter of the sale, notwithstanding the demands made upon him for this purpose.

The trial court rendered judgment in behalf of the defendant, holding the contract of sale to be rescinded and ordering the return to the plaintiff the Php 3,000 paid on account of the price, together with interest thereon at the rate of 10 percent per annum. From this judgment, the plaintiff appealed.

ISSUE:

Whether or not, the defendant has the right to demand the rescission of the sale and return of payment.

RULING:

Yes. It is evident, then, that the mere execution of the instrument was not fulfilled by the appellant's obligation to deliver the thing sold, and that from such non-fulfillment arises the defendant's rights to demand, as demanded the rescission of the sale and return of the payment.

In as much as the rescission is made by virtue of the provisions of law and not by the contractual agreement, it is not the conventional but the legal interest that is demandable.

It is therefore held that the contract of purchase and sale entered into by and between the plaintiff and the defendant on June 11, 1914, is rescinded, and the plaintiff is ordered to make restitution of the sum of Php 3,000 received by him on account of the price of the sale, together with interest thereon at the legal rate of 6 percent per annum from the date of the filing of the complaint until payment, with the costs of both instances against the appellant. So ordered.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Judges speaking softly

What They Long for When They Read

Do you ever stay up nights wondering what judges want?

At least in briefs and motions?

I recently surveyed more than a thousand state and federal judges, both trial and appellate.

Respondents ranged from state trial-court judges to U.S. Supreme Court justices.

The good news:

Judges agree on much more than many litigators might think, and I found no major differences based on region or type of court.

More good news:

When judges are surveyed anonymously, they’re blunt and sometimes even funny.

The bad news:

Other than the briefs by the brightest lights of the appellate bar, almost every filing I see violates the wish lists of the judges I surveyed.

Here is some guidance, along with some choice anonymous quotations about what judges want but too often don’t get.

For starters, watch how you name names.

Use the parties’ names rather than their procedural affiliation.

Prefer words to unfamiliar acronyms, even if the word or phrase is longer.

Avoid defining obvious terms like “FBI” and “Ford Motor Company.”

And for the terms you do define, put the defined term in quotation marks and then get out of Dodge.

All four of these techniques make “legal writing” feel more like “writing.”

“I absolutely detest party labels (plaintiff, debtor, creditor, etc.). Name names, for God’s sake!”

“Don’t use ‘plaintiff,’ ‘defendant,’ ‘appellant,’ or ‘appellee’ in the brief because we may forget who’s who.

Instead, use names for individuals and business titles for companies.”

“Avoid defining obvious terms.

If a party is Apple Computer Corp., why include the parenthetical (‘Apple’)?

If the plaintiff’s name is Henry Jackson and he’s the only Jackson in the case, why the need to identify him as Henry Jackson (‘Jackson’)?

If the case is about one and only one contract, when first identifying it, why the need for (the ‘Contract’)?”

“I truly dislike acronyms. I would much rather have ‘North River Insurance Cooperative’ referred to as ‘the insurer’ or ‘the cooperative’ or ‘North River’ than as ‘NRIC.’”

“‘Hereinafter defined as’ (or anything like it) is pretty awful.”

“Avoid defined terms (“terms”) altogether.”

Keep your language choices classy.

As if on cue, almost all litigators and appellate lawyers are happy to endorse a ban on emotional or hyperbolic rhetoric.

The problem is that those same lawyers often grant themselves an exemption, as if their opponents are so singularly awful or imbecilic that even the snarkiest tone is warranted.

In fact, lawyers often tell me that they absolutely must point out how disingenuous their opponent is, because otherwise the court won’t see it.

Solution: Show, don’t tell.

“‘Disingenuous’ is a perfectly fine word that the legal profession has turned into the wild card disparagement of the other side’s argument.”

“Don’t use ‘specious.’”

“Avoid phrases and sentences that reflect a lack of civility. Don’t belittle the other side’s arguments but rather focus on your own strengths.”

“I hate ‘speciously,’ ‘frivolously,’ ‘disingenuously,’ and other shots at counsel or the other party.”

“Don’t write ‘ridiculous.’”

“I hate ‘laughable.’”

“Words such as ‘clearly,’ ‘plainly,’ ‘obviously,’ ‘absurd,’ ‘ridiculous,’ ‘ludicrous,’ ‘baseless,’ and ‘blatant’ are crutches intended to prop up arguments that lack logical force. They can never make a weak argument credible or a strong argument even stronger. So why bother with them?”

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. once said that you should strike at the jugular and let the rest go.

If you write motions and briefs for a living, you can manifest Holmes’s maxim many times a day.

Start by cutting stuffy introductory formulas beset with such archaic language as “by and through undersigned counsel.”

Reduce well-trodden standards and tests to their essence.

Hack away at needless procedural detail.

And then, at the sentence level, slash windups and throat-clearing.

“Avoid long introductions such as ‘Plaintiff, by and through undersigned counsel, hereby submits its Reply Memorandum in response to _.

This Reply is accompanied by the following Memorandum of Points and Authorities.’

I know that counsel is filing the brief on behalf of his or her client.

I can see in the caption that the filing is a reply, and I can also see that there is a memorandum of points and authorities.”

“Avoid grammatical expletives (‘there is,’ ‘it is’).”

“‘It should be noted that,’ ‘it is beyond doubt that,’ and the like waste space.”

“Writing numbers out twice seems particularly useless.”

“Is it really necessary to devote a page or more or even half a page to discussing the standard of review for summary judgment or a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim?”

“The procedural history does not need to go back to the Creation. Just summarize what is relevant to the issue specifically before the court.”

“Most sentences are dramatically improved by omitting testimony references: ‘Smith [testified that he] went to the scene the following day.’

While some discussion of trial testimony is necessary when you are talking about hearsay or impeachment, those discussions are best left to highlight after you’ve told the story the reader needs to understand.”

“There’s a real danger in stuffing factual sections with crud.”

With judges becoming ever more impatient readers, looks do matter.

Out: long, uninterrupted blocks of text.

In: timelines, maps, graphs, diagrams, tables, headings and subheadings, and generous margins.

“Sometimes a timeline is clearer than an essay format.”

“I ALWAYS appreciate a clear timeline of events and I am happy to have that in the text of the fact section or as an exhibit. I want one place where I can see when everything happened in the case if it’s not a singular event.”

“Just as I don’t like scrolling down to find authority in a foot-note, I don’t like flipping through clerks’ papers or exhibits to find a key piece of documentary evidence that is discussed in a brief. The use of pictures, maps, and diagrams not only breaks up what can be dry legal analysis; it also helps us better understand the case as it was presented to the trier of fact (who undoubtedly was permitted to see an exhibit while it was discussed).”

“When a case involves analysis of a map, graph, or picture, I would like to see attorneys include a copy of the picture within the analysis section of the brief.”

“I like fact sections broken down with headings and even subheadings.

Define chapters in the facts or the ‘next’ relevant event.”

I was surprised that the judges I surveyed were more open to bolding and italics than judges used to be.

Perhaps this evolution stems from their desire not to wade through paragraphs that look and feel the same. Or

maybe the internet has accustomed all of us to formatting bells and whistles.

That said, even judges who don’t mind emphasis want it in small doses.

And although the judiciary may be split on emphasis, every judge in the country appears to hate all caps, and few are fans of underlining.

“Party names should not be in all caps.”

“Headings in all caps are difficult to read.”

“All caps are completely beyond the pale.”

“If a lawyer feels that emphasis is needed, I always prefer italics to boldface type. Boldface signals to me ‘Just in case you’re too stupid to recognize what’s important.’”

Let’s move on to specific language choices.

One question on my survey simply asked judges to list words and phrases they dislike.

Few responses surprised me, but it was amusing to see how easily many judges could rattle off language choices that drive them crazy.

They must have lots of exposure!

As the list below suggests, many lawyers are unaware of how often they use these words and phrases.

Never confuse knowing that you should avoid a term with actually implementing that knowledge in your writing.

“Death to modifiers!”

“I don’t like any clunky legalese like ‘For the foregoing reasons,’ ‘heretofore,’ etc.”

“‘Wherein,’ ‘heretofore,’ ‘aforesaid,’ ‘to wit’: they all should go the way of the dodo bird.”

“Don’t use ‘at that time’ for ‘when.’”

“Don’t use anything like ‘s/he.’”

“I dislike formalistic terms that people don’t really use in ordinary life like ‘wherefore’ and ‘arguendo,’ unnecessary phrases like ‘[party] submits,’ and derogatory terms like ‘asinine’ used to describe the opposing party’s argument.”

“Don’t use ‘prior to’ for ‘before’ or ‘subsequent to’ for ‘after.’”

“I dislike ‘notwithstanding,’ ‘heretofore.’”

“Don’t use words like ‘wherefore,’ ‘heretofore,’ ‘hereinafter’ that aren’t commonly used in everyday language.”

“Don’t write ‘Pursuant to.’”

“I believe ‘hereby,’ ‘hereinafter,’ ‘foregoing’ and other arcana have no place in modern legal writing.”

“I do not care for ‘the instant’ anything.”

“Tell them to stop writing ‘In the case at bar’!”

“I don’t like unnecessary Latin phrases like ‘inter alia.’”

“Get rid of the formalisms from the Middle Ages such as ‘Comes now Plaintiff, by and through his undersigned attorneys.’”

“‘Aforesaid,’ ‘heretofore,’ etc. are all pretty much empty and add nothing. Same with ‘said,’ as in the ‘said contract was signed at the said meeting.’”

“I loathe the word ‘utilize.’”

“I do not like when lawyers tell me what I ‘must’ do. Just say that the court ‘should’ do something.”

“‘Unfortunately for appellee’ (or for any party) should never appear in briefs.”

Another category of language irritation:

Many lawyers are surprised when I tell them that judges really don’t find “respectfully submits” and “respectfully requests” to be, well, respectful.

Cloying is more like it.

And my survey results were right in line with my anecdotal experience.

“Don’t write ‘Defendant respectfully requests.’ I prefer it if you just say what you want to say. I’ll know if it’s respectful or not!”

“‘Respectfully submits’ or ‘it is our position that’ are wasted words: they communicate nothing, except potential insecurity about the argument that follows.”

“Avoid ‘with all due respect.’”

“Avoid phrases such as ‘respectfully submits that’ that can be stated in one word like ‘contends.’”

On the less-is-more theme, you’ll rarely if ever hear judges complain that sentences or briefs are too short.

And yet, sometimes short is, in fact, too sweet.

Two offenders: random “this” and “that” references such as “this proves” or “that explains.”

Also, especially for traditionalist judges in the Justice Scalia mold, avoid contractions.

“I do not like indefinite references and see the word ‘this’ used too often. It should be used in conjunction with another word such as ‘this argument’ or ‘this logic.’”

“I REALLY dislike contractions. They make the argument sound like casual conversation and they give the writer an arch voice.”

When it comes to usage as opposed to word choice, American judges fall into three categories:

(1) those who understand the finer points of usage and care (these are the judges who ask me in workshops about “pleaded” versus “pled,” predicate nominatives,

and the counterfactual subjunctive);

(2) those who understand the finer points of usage but either don’t notice or don’t care, and

(3) those who don’t know enough about usage to notice mistakes.

“I despise the use of ‘impact’ as a verb.”

“Learn to differentiate between ‘that’ and ‘which.’”

“I cannot stand ‘As such’ used as a synonym for ‘Therefore.’”

“Learn to use the subjunctive!”

Now let’s talk about fact sections, and in particular dates.

Whenever I relay judges’ irritation with needless dates, someone in the audience retorts that some dates really matter.

Well, that’s why judges object to needless dates.

And it’s not as if you face a binary choice between a full date and nothing at all.

Sometimes a word or phrase will do the trick.

“It helps to vary how the passage of time is described. Instead of ‘on May 26, 2016,’ it’s refreshing to read ‘the next week’ or ‘two months later.’”

“Dates are rarely essential and often overused. If I see a date, I assume it is important. If it’s not, you have interrupted the flow of your argument for no good reason.”

“I HATE specific dates that have no relevance. I keep thinking the 24th day of September must really be important, for example, and then when it isn’t, I’m unhappy I’ve spent brainpower waiting for writer to tell me why it was critical!”

“Sometimes it’s enough to refer to an event as ‘mid-2015’ rather than a specific date.”

“If two parties entered into a contract, and it makes no difference to the claim whether they did so on January 22, 2014, or March 6, 2015, leave the date out.”

Now let’s talk a bit about the beginning of motions and briefs.

Don’t short the introduction.

Judges find strong introductions invaluable.

They help lawyers hone their theory of the cases, and they help shape the fact section and legal argument to come.

“Explain why you should win on the first page. ‘The Court should deny Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment for the following three reasons.’”

“I’ve had briefs in fairly involved cases without executive summaries. I’ve likened reading them to putting together a jigsaw puzzle without having the cover of the box to know what the puzzle is supposed to look like when it’s done.”

“I do appreciate a good ‘statement of the case’ section, particularly in complex civil appeals, in which, in a non-argumentative manner, the lawyer sets the stage for what issues the court is called upon to decide. That helps me focus on what facts and portions of the record will be most relevant to those issues.”

How about cases and other authorities?

Busy judges have become increasingly irritated with the way many litigators handle case law.

Facile shorthand: “Too many and too much.”

But it’s a bit more complicated than that.

One common complaint is that many litigators appear to search case law databases for choice language even if a given case doesn’t quite fit and even if the case doesn’t come down procedurally the way the lawyer wants the current case to.

“The main issue I run across is probably a function of Boolean searches: citations to ‘blurbs’ or quoted phrases within published decisions where the actual ruling, or the analysis, or the posture of the case is completely distinguishable (or even adverse) to the point the party is trying to make. I am much more persuaded by one or two authorities that are carefully analyzed and applied than by a sprinkling of quotations lifted from a dozen cases that are strung together.”

It’s also surprising how many cases some lawyers cite for a proposition that their opponents would never challenge, such as the summary judgment standard, the Daubert standard, or the standard of review.

“For well-established law, such as the standard of review, I prefer only a single cite.”

“Cite just enough cases and not all cases. One controlling case is enough. For non-controlling cases, if there aren’t any contrary or many contrary cases, cite two or three non-controlling cases, preferably the two or three most recent. If there are two contrary groups of cases and none is controlling, then it might be appropriate to cite one from each jurisdiction supporting the writer’s side.”

Once you know which cases to cite and how many, what should you do with them?

On the one hand, most judges rail against including too many facts and too many quotations when it would be more effective to use a concise parenthetical or a pithy quoted phrase merged into a sentence about your own case.

On the other hand, for complex or dispositive cases, some judges find that lawyers use a parenthetical when a fuller textual description would be more apt.

Ask yourself this question: “If I were being asked to endorse proposition X, what would I need to know about case Y to be comfortable doing so?”

And then don’t write one more word.

“Skip the long description. Just state the damn proposition, cite the damn case, and be done with it.”

“Long discussions of the facts of cited cases are often not helpful.”“For the most important case, cover the important points in text, not in an explanatory parenthetical. But it’s okay to use explanatory parentheticals for the cases that support the main one.”

“I prefer citation to one or two cases with a short, pertinent explanation in a parenthetical. I prefer a full paragraph for distinguishing an adverse authority. I don’t prefer distinguishing adverse authority in a footnote.”

“I prefer that briefs directly address contrary authority organized by argument, not by case name.”

That brings me to the block-quote question.

Most lawyers defend block quotes by insisting that they convey pivotal information that can’t be paraphrased.

That may be true, but here’s the bad news about that “pivotal information”:

If it’s presented in a block quote, judges are likely to skip it entirely.

So meet judges halfway:

Use block quotes only when the language of the text itself adds value.

Use block quotes as little as possible.

And introduce block quotes substantively and persuasively, focusing less on who said what and more on why the reader should care.

“Do not block quote more than three lines. After that, I may stop reading.”

“Don’t write ‘As follows:’ before quotes. Just use the colon; the ‘as follows’ is implied.”

“Fold quotes into text if possible.”

“Huge block quotes are terrible. It’s much more persuasive to paraphrase the reasoning and then quote only the crucial lan- guage.”

“When quoting, do not overuse brackets—I call them punctuational potholes. If you’re quoting from a case, start the quote after the part of the sentence that makes you want to use a bracket. The same for quotes from the record. For example, instead of ‘The officer stated, “[i]f [we] catch [you] in [the area] again, if [you] don’t have something, [I]’ll make sure [you] have something,” put ‘The officer said that if Smith were ever caught in the neighborhood again and did not “have something,” the officer would make sure he did have something.’”

One last issue.

Even after Justice Scalia’s passing, the debate over where to put citations rages on.

But with so many judges reading briefs on iPads or on other devices that require scrolling to see footnotes, 78 percent of the judges in my survey prefer to see citations in the text, the old-fashioned way.

You should still try to avoid putting citations at the beginning or in the middle of your sentences.

And, of course, some judges (12 percent in my survey, with the other 10 percent neutral) do love to see citations in footnotes, but those judges nearly always make their views known.

“This is a show-your-work gig, and I need to see your work there—not go hunting for it. This is a bigger deal now, I think, since we all read electronically.”

“We want to process the citation as we read. When a litigant makes a point, it matters if he or she is citing to a Supreme Court case, a circuit opinion, a treatise, etc. I don’t want to have to stop reading and look down and find the citation in the footnote or endnote. I understand the reasons some endorse it, but it is not practical for briefs and opinion writing, and everyone I work with hates that style of writing.”

“I find citations in footnotes to be distracting. It also makes the case more difficult to read online such as in Westlaw.”

Here’s the bottom line: Just as many associates in law firms think that knowing individual partner preferences is all there is to writing, many seasoned litigators think the same about knowing the preferences of individual judges.

Sure, there’s something satisfying about finding out whether a given judge likes the Oxford comma.

(Since I brought it up, 56 percent of the judges I surveyed said they do, 21 percent said they don’t, and 23 percent said they don’t care).

And it’s all too tempting to make brief writing mostly about rules and formatting preferences.

But I suggest that both litigators and appellate advocates spend most of their energies developing the core persuasive writing skills that would make almost all judges much happier.

So shoot for strong, compelling, yet concise introductions; a restrained use of case law, with quality over quantity; a readable treatment of party names and industry lingo; helpful leadins to block quotations; a confident and professional tone; modern diction; and more white space, headings, and visual aids.

In a word, show empathy for the reader.

And for those of you thinking that judges should practice in their opinions what they preach to lawyers about their briefs, that topic will have to be for another article!

Shoot for strong, compelling, yet concise introductions; a restrained use of case law; and modern diction.

0 notes

Text

Article 1161 of the New Civil Code

ARTICLE 1161. Civil obligations arising from criminal offenses shall be governed by the penal laws, subject to the provisions of article 2177, and of the pertinent provisions of Chapter 2, Preliminary Title, on Human Relations, and of Title XVIII of this Book, regulating damages. (1092a)

Article 1161 refers to civil obligations arising from crimes. Article 100 of the Revised Penal Code provides that, "every person criminally liable is also civilly liable." The scope of the civil liability includes:

a. Restitution - act of giving back something that has been lost or stolen.

b. Reparation of the damage caused - restoring in good condition of something that has been damaged.

c. Indemnification for consequential damages - compensation of a person for damages or losses.

The kinds of damages under Title XVIII of the Civil Code are:

Actual or Compensatory Damages

Moral Damages

Nominal Damages

Temperate or Moderate Damages

Liquidated Damages

Exemplary or Corrective Damages

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE, VS. MELFORD BRILLO Y DE GUZMAN, ACCUSED-APPELLANT.

G.R. No. 250934, June 16, 2021

Facts:

On October 1, 2010, the victim, who was then 15 years old, accompanied her friend to see the latter’s boyfriend. The boyfriend was with 6 of his friends including the accused. They proceeded to a drinking spree at a house of one of the friends. All of them drank liquor except for the victim who drank juice. She was forced to drink liquor by 5 of the friends including the accused. The victim got dizzy so she slept in a bedroom. Around 9:00 in the evening, she woke up naked and saw the accused was naked too. The accused forced her to a sexual intercourse.

On October 4, 2010, the victim underwent medico-legal examination. There were lacerations and contusions found on her genitalia.

Issue:

Whether the accused is guilty of the crime of rape.

Ruling:

Yes. The victim was only 15 years old while the accused is 21 years old. It was impossible for her to give consent on any sexual advances because she was drunk. The sexual assault was further proved by the Medico-Legal Certificate. Further, if the victim was not truthful to her accusation, she would not have opened herself to a public trial and humiliation.

The SC found the accused guilty beyond reasonable doubt of the crime of rape and sentenced him to reclusion perpetua. The court further ordered the accused to pay the victim 75,000 for civil indemnity, 75,000 for moral damages and 75,000 for exemplary damages.

Civil indemnity proceeds from Article 100 of the RPC, which states that "every person criminally liable is also civilly liable." Its award is mandatory upon a finding that rape has taken place.ℒαwρhi৷

Moral damages are awarded to "compensate one for manifold injuries such as physical suffering, mental anguish, serious anxiety, besmirched reputation, wounded feelings, and social humiliation.

Finally, exemplary damages may be awarded against a person to punish him for his outrageous conduct.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Case Related to Art 1167

Chavez vs. Gonzales: G.R. No. L-27454; April 30, 1970

Rosendo O. Chavez, plaintiff-appellant vs. Fructuoso Gonzales, defendant-appellee

REYES, J.B.L., J.:

FACTS:

The plaintiff delivered to the defendant, who is a typewriter repairer, a portable typewriter for routine cleaning and servicing. The defendant was not able to finish the job after some time despite repeated reminders made by the plaintiff. In October, 1963, the defendant asked from the plaintiff the sum of P6.00 for the purchase of spare parts, which amount the plaintiff gave to the defendant.

After getting exasperated with the delay of the repair of the typewriter, the plaintiff went to the house of the defendant and asked for the return of the typewriter. The plaintiff found out that the typewriter was in shambles with some parts missing. Chaves demanded the return of the missing parts and the sum of P6.00, which Gonzales returned. Later on, the plaintiff had his typewriter repaired by Freixas Business Machines, and the repair job cost him a total of P89.85, including labor and materials.

Chavez then commenced this an action before the City Court of Manila, demanding from the Gonzales the payment of P90.00 as actual and compensatory damages. The RTC granted the petition and ordered that the defendant pay the plaintiff the amount of P31.10 which is the total value of the missing parts. Chavez contended that he should be awarded the whole cost of labor and materials as provided for in Article 1167 of the Civil Code. Thus, this petition.

ISSUE: Whether or not Chavez is entitled to the whole cost of labor and materials that went into the repair of the typewriter?

RULING: YES. Article 1167 of the Civil Code states: If a person obliged to do something fails to do it, the same shall be executed at his cost. This same rule shall be observed if he does it in contravention of the tenor of the obligation.

The inferences derivable from these findings of fact are that the Chavez and the Gonzalez had a perfected contract for cleaning and servicing a typewriter, intended to be completed at some future time although such time was not specified, that such time had passed, and that the typewriter was returned cannibalized and unrepaired, which in itself is a breach of his obligation. The time for compliance had evidently expired and there was a breach of contract by non-performance. The Gonzales-appellee contravened the tenor of his obligation.

The cost of the execution of the obligation in this case should be the cost of the labor or service expended in the repair of the typewriter, which is in the amount of P58.75 because the obligation or contract was to repair it. In addition, Gonzales is likewise liable under Article 1170 of the Code for the cost of the missing parts for in his obligation to repair the typewriter he was bound, but failed or neglected, to return it in the same condition it was when he received it.

The appealed judgment is modified. Gonzales to pay Chavez the sum of P89.85 with interest.

0 notes

Text

ARTICLE 104. Whenever the liquidation of the community properties of two or more marriages contracted by the same person before the effectivity of this Code is carried out simultaneously, the respective capital, fruits and income of each community shall be determined upon such proof as evidence.

In case of doubt as to which community the existing properties belong, the same shall be divided between or among the different communities in proportion to the capital and duration of each.

The law specifies the procedure in the liquidation of the community properties of two or more marriages where it is being carried out simultaneously.

In the case of Vda. De Delizo v. Delizo, 69 SCRA 216, the Supreme Court held that if one marriage lasted for 18 years and the other for 46 years, the properties should be divided in the proportion of 18 to 46, if the capital of either marriage or the contribution of each spouse cannot be determined with mathematical certainty.

ROSARIO OÑAS, appellant, VS CONSOLACION JAVILLO, appellees, 59 Phil. 733

GODDARD, J,:

FACTS:

This is an appeal from an order of the Court of First Instance approving a project of partition of the property belonging the deceased Crispulo Javillo died on May 18, 1927 in the municipality of Sigma, Capiz.

Crispulo Javallo contracted 2 marriages, the first one was with Ramona Levis with 5 children, the second marriage was with Rosario Onas with 4 children.

Santiago Andrada was the appointed administrator of his Estate. The first project of partition was disapproved by the lower court and the second project of partition (subject of appeal). The appellant filed an appeal alleged that the lower court committed the error.

ISSUE: Whether or not the lower court erred in holding that all properties acquired during the 2nd marriage were acquired with the products of the properties of the 1stmarriage.

RULING:

Crispulo Javillo lived for 20 years after his 2nd marriage with Rosario Onas and acquired 20 parcels of lands during that marriage. Only 11 parcels of lands were acquired during 1st marriage.

It is hard to believe that the products of 11 parcels of lands supplied all of the capital used in acquiring the 20 parcels of land.

In this case, it does not appear that there was a liquidation of partnership property of the 1st marriage.

Levis Marriage : ½ of the conjugal property should be divided among the

5 children (11 parcels of land and 5 carabaos)

Onas Marriage : ½ of the conjugal property must be adjudicated to the

widow Rosario Onas.

Here, the judgement of the lower court was reversed and this case remanded for further proceedings in conformity with the decision.

0 notes

Text

Navigating Legal Appeals: Understanding the Process with the Best Lawyer in Delhi, Lawchef

Introduction: In the realm of law, appeals play a crucial role in seeking justice and redressal for aggrieved parties. Whether in civil or criminal cases, the appellate process offers an avenue for parties dissatisfied with a court's decision to have their case reviewed by a higher authority. In Delhi, where legal complexities abound, having the guidance of the best lawyer is paramount. Lawchef, renowned for its expertise in appellate advocacy, sheds light on the intricacies of the appeal process.

Understanding the Process of Appeal: An appeal is a legal proceeding where a higher court reviews the decision of a lower court to determine if any errors were made. It provides parties with an opportunity to challenge adverse rulings, errors in law, procedural irregularities, or incorrect application of facts. The appellate process typically involves several stages, each with its own set of rules and procedures.

Filing Notice of Appeal: The process begins with the filing of a Notice of Appeal within the prescribed timeframe, usually within a specified number of days after the lower court's judgment or order is pronounced. The notice must contain essential details such as the parties' names, the court's name and case number, and the specific rulings being challenged.

Record Preparation: Once the Notice of Appeal is filed, the appellate court requests the lower court to prepare and transmit the record of proceedings, including transcripts, pleadings, evidence, and court orders. The record serves as the basis for the appellate court's review and consideration of the case.

Appellate Briefs: Both the appellant (the party appealing) and the appellee (the opposing party) are required to submit appellate briefs outlining their respective arguments, legal authorities, and supporting evidence. These briefs provide a comprehensive overview of the issues raised on appeal and help the appellate court understand the parties' positions.

Oral Arguments: In some cases, the appellate court may schedule oral arguments to allow the parties' lawyers to present their case and respond to questions from the judges. Oral arguments provide an opportunity for clarifying complex legal issues, highlighting key arguments, and addressing any concerns raised by the court.

Appellate Decision: After reviewing the record, briefs, and oral arguments, the appellate court issues its decision, either affirming, reversing, modifying, or remanding the lower court's judgment or order. The appellate decision is typically accompanied by a written opinion explaining the rationale behind the court's ruling.

Role of Lawchef in the Appeal Process: As the leading legal firm in Delhi, Lawchef brings unparalleled expertise and experience to the appellate process. With a track record of success in appellate advocacy, Lawchef's team of skilled lawyers provides strategic guidance and representation to clients seeking redressal through appeals.

Case Evaluation: Lawchef conducts a thorough evaluation of the case to assess the grounds for appeal, identify legal errors or issues, and determine the likelihood of success on appeal. Based on this assessment, Lawchef develops a comprehensive strategy tailored to the client's objectives and interests.

Brief Drafting: Lawchef's lawyers meticulously draft appellate briefs, employing persuasive arguments, legal precedents, and statutory provisions to effectively advocate for the client's position. The briefs are crafted with precision and clarity to convey complex legal concepts in a compelling manner.

Oral Advocacy: In cases where oral arguments are scheduled, Lawchef's lawyers leverage their oral advocacy skills to articulate the client's arguments persuasively before the appellate court. With a keen understanding of procedural rules and courtroom etiquette, Lawchef's lawyers present a compelling case on behalf of their clients.

Diligent Representation: Throughout the appellate process, Lawchef provides diligent representation, ensuring that the client's rights are protected, procedural requirements are met, and deadlines are adhered to. Lawchef's unwavering commitment to excellence and client satisfaction sets it apart as the premier choice for appellate advocacy in Delhi.

Conclusion: The process of appeal is a vital mechanism for seeking justice and correcting legal errors in the judicial system. With the guidance of the best lawyer in Delhi, Lawchef, aggrieved parties can navigate the complexities of the appellate process with confidence and clarity. From case evaluation to oral advocacy, Lawchef's expertise and advocacy ensure effective representation and favorable outcomes for clients seeking redressal through appeals. Trust in Lawchef's proficiency and dedication, and rest assured that your appellate case is in capable hands.for more https://www.lawchef.com/service/appeal

0 notes

Text

Round 5:

Section 5. Dissolution of Absolute Community Regime

Article 99. The absolute community terminates:

1. Upon death of either of the spouse;

2. When there is a decree of legal separation;

3. When the marriage is annulled and when void; or

4. In the judicial separation of properties of marriage under Articles 134 to 138.

The termination of community property should be registered so that the third party will not be prejudiced when the surviving spouse decides to enter into a contract or sells properties from the community property. If actions is to be brought, it must be done with the surviving spouse.

The termination of community property in legal separation, the modes of termination of the absolute community properties are exclusive in nature, and shall require approval of the court. Any change or modification after the declaration of marriage will require judicial intervention.

In the dissolution of community property, whatever is acquired by the spouses thereafter belongs to him/her exclusively. At the same time, debts contracted are answerable by him/her exclusively.

_____________________

G.R. 7397, December 11, 1916

Case of Amparo Nable Jose, et.al., Standard Oil Insurance Company of New York and Carmen Castro, Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

Mariano Nable Jose, et.al., Defendants-Appellees

Facts:

In 1880, Mariano Nable Jose got married to Dona Paz Borja and had four children. Dona Paz died intestate in 1898 and left her husband and children as her heirs. Since the death of the spouse, the community partnership between Mariano and Dona Paz has not been liquidated, and no proceedings was issued for the judicial administration of the properties.

Mariano got in indebted and mortgaged the properties to Amparo Nable Jose de Lichauco and Asuncion Nable Jose, Standard Oil Company. The properties were also encumbered to Carmen Castro. The children as heirs had no knowledge about the mortgages nor informed by their father. In order to recover payments from debts, the Standard Oil Company filed actions against Mariano.

Issue:

Is the sale or mortgaged by the surviving spouse of the community property valid?

Held:

Yes, the court held that it is valid.

In law, the court held that the petitioner, Mariano, is clothed by exclusive possession and insignia of power in the disposal of properties. It imposes rights and duties to sell all or part of the community property.

The Court further held that the proceeds of the sale of the property should be applied as payment to the third parties, Amparo Nable Jose de Lichauco and Asuncion Nable Jose of the Standard Oil Company, and Carmen Castro.

For the share of the heirs, Articles 1424 and 1426 of the Civil Code should also apply.

Article 1424 states that after deductions of inventoried properties, the remainder of the states shall composed the assets of the conjugal property.

Article 1426 states that the remainder of the assets shall be divided, shared and likewise shared alike to the husband, the wide, and to the respective heirs.

In the case, Mariano acted fraudulently when he took away the proceeds of the community property, which should be divided, shared and shared alike to the husband, the wife, and to respective heirs. The heirs tried to recover the properties by they failed. The court erred to hold the proceeds of the sale of the remaining properties after deductions of debts.

0 notes

Text

Lopez & Angeles vs CA Aug 1, 2018

Topic: EXTINGUISHMENT OF AGENCY Art. 1919(3) in relation to Articles 1930 and 1931

Doctrine

The general rule is that the death of the principal or, by analogy, the agent extinguishes the contract of agency and any act by the agent subsequent to the principal’s death is void ab initio, unless any of the circumstances provided for under Article 1930 or Article 1931 obtains; in which case, notwithstanding the death of either principal or agent, the contract of agency continues to exist.

Note: Elements of a Contract of Agency was also mentioned which are:

There must be consent coming from persons or entities having the juridical capacity and capacity to act to enter into such contract;

There must exist an object in the form of services to be undertaken by the agent in favor of the principal; and

There must be a cause or consideration for the agency.

SUPER SUMMARY

Primex Corporation entered into a Deed of Conditional Sale with Marcelino Lopez for a portion of land containing more or less 140,029 sqm at an agreed price of P39,208,120.00. Due to the failure of Lopez to fulfill its obligation to deliver the land title, Primex filed a complaint against him for specific performance. Trial ensued until the parties, on February 21, 2012, submitted a Compromise Agreement with Joint Motion to Dismiss and Withdrawal, entered by the petitioners through Atty. Angeles. Not long after, the heirs of Marcelino Lopez assailed the validity of the agreement arguing that Atty. Angeles had no authority to do so. In the same vein, the Lopezes argued that although Atty. Angeles was Marcelino’s lawyer, his authority ceased to exist upon Marcelino’s death, rendering now his subsequent acts on behalf of Marcelino null and void. Is the contention of the petitioners, correct?

AFFIRMATIVE. Atty. Angeles had ceased to be the agent upon the death of Marcelino Lopez, therefore Atty. Angeles’ execution and submission of the Compromise Agreement in behalf of the Lopezes by virtue of the special power of attorney executed in his favor by Marcelino Lopez were void ab initio and of no effect. The special power of attorney executed by Marcelino Lopez in favor of Atty. Angeles had by then become functus officio.

FACTS:

On 12 September 1989, PRIMEX, as vendee, entered into a Deed of Conditional Sale (DCS) relative to a portion of land containing more or less 140,029 sqm from a mother parcel of land comprising an area of more or less 198,888 square meters located along Sumilong Highway, Barrio La Paz, Antipolo, Rizal, with Marcelino Lopez et. al. The parties agreed at a purchase price of P39,208,120.00

PRIMEX claims that it has fulfilled all its financial obligations under the contract and is ready to pay another P2,000,000.00. However, instead of receiving a valid title, the defendant-appellees delivered a Transfer Certificate of Title that was derived from an Original Certificate of Title declared null and void by the Supreme Court. As a result, PRIMEX refused to accept this title as valid and declined to release the additional payment according to the agreed schedule.

As compulsory counterclaim, the Lopezes on the basis of PRIMEX’s allegedly serious and wanton breach of the terms of the DCS, sought for the rescission of the contract. They also asked for damages and the dismissal of PRIMEX’s complaint, notwithstanding the fact of their acknowledgement that in the interim, and as of 07 March 1993, PRIMEX already released several payments amounting to P24,892,805.85 for the subject property, excluding a separate P4,150,000.00 loan covered by a real estate mortgage it extended to the defendant-appellee, Rogelio Amurao for the purpose of funding additional expenses incurred in relation to the fulfillment of the defendant-appellees obligations under the DCS.

[This digest will not include the details of the trial, particularly how the parties exhausted their procedural rights. Instead, we jump now to the point in time where the Lopezes assailed the validity of the Compromise Agreement with Joint Motion to Dismiss and Withdrawal entered and submitted into by Atty. Angeles on February 21, 2012, lawyer of one of the petitioners – Marcelino Lopez.]

It is noted at this juncture that because the petitioners had engaged the services of two different attorneys, Atty. Sergio Angeles and Atty. Martin Pantaleon, another issue concerning the timeliness of the Motion for Reconsideration filed by the petitioners arose.

On March 7, 2012, the Court issued the resolution being challenged by the heirs of the late Marcelino Lopez: (1) noting the Compromise Agreement with Joint Motion to Dismiss and Withdrawal of Petition; (2) granting the Joint Motion to Dismiss and Withdrawal of Petition; and (3) denying the petitions for review on certiorari on the ground of mootness. Thereafter, the heirs of Marcelino Lopez filed their oppositions arguing that Atty. Angeles no longer had the authority to enter into and submit the Compromise Agreement because the special power of attorney in his favor had ceased to have force and effect upon the death of Marcelino Lopez.Contention of Atty. Angeles: The Lopezes authorized him to enter into the Compromise Agreement; and that his authority had formed part of the original pretrial records of the RTC.

ISSUE/S

Whether or not the authority of Atty. Angeles was terminated upon the death of Marcelino Lopez.

RULING

The Court ruled in the AFFIRMATIVE.

One of the modes of extinguishing a contract of agency is by the death of either the principal or the agent. In Rallos v. Felix Go Chan & Sons Realty Corporation, the Court declared that because death of the principal extinguished the agency, it should follow a fortiori that any act of the agent after the death of his principal should be held void ab initio unless the act fell under the exceptions established under Article 193016 and Article 193117 of the Civil Code.

The exceptions should be strictly construed. In other words, the general rule is that the death of the principal or, by analogy, the agent extinguishes the contract of agency, unless any of the circumstances provided for under Article 1930 or Article 1931 obtains; in which case, notwithstanding the death of either principal or agent, the contract of agency continues to exist.

Marcelino Lopez died on December 3, 2009, as borne out by the Certificate of Death submitted by his heirs. As such, the Compromise Agreement, which was filed on February 2, 2012, was entered into more than two years after the death of Marcelino Lopez.

Considering that Atty. Angeles had ceased to be the agent upon the death of Marcelino Lopez, Atty. Angeles’ execution and submission of the Compromise Agreement in behalf of the Lopezes by virtue of the special power of attorney executed in his favor by Marcelino Lopez were void ab initio and of no effect. The special power of attorney executed by Marcelino Lopez in favor of Atty. Angeles had by then become functus officio. For the same reason, Atty. Angeles had no authority to withdraw the petition for review on certiorari as far as the interest in the suit of the now-deceased principal and his successors-in-interest was concerned.

The want of authority in favor of Atty. Angeles was aggravated by the fact that he did not disclose the death of the late Marcelino Lopez to the Court. His omission reflected the height of unprofessionalism on his part, for it engendered the suspicion that he thereby tried to pass off the Compromise Agreement as genuine and valid despite his authority under the special power of attorney having terminated for all legal purposes.

Accordingly, the March 7, 2012 resolution granting the Joint Motion to Dismiss and Withdrawal of Petition is set aside, and, consequently, the appeal of the petitioners is reinstated.

0 notes

Text

G.R. No. L-8883 July 14, 1959

ALFREDO M. VELAYO, ETC., plaintiff,

vs.

SHELL COMPANY OF THE PHILIPPINES ISLANDS, LTD., defendant-appellee.

ALFONSO Z. SYCIP, ET. AL., intervenors-appellants.

Sycip, Quisumbing, Salazar and Associates for appellants.

Ozaeta, Lichauco and Picazo for appellee.

On December 17, 1948, Alfredo M. Velayo as assignees of the insolvent Commercial Airlines, Inc., instituted an action against Shell Company of the Philippine Islands, Ltd., in the Court of First Instance of Manila for injunction and damages (Civil Case No. 6966).

On October 26, 1951, a complaint in intervention was filed by Alfonso Sycip, Paul Sycip, and Yek Trading Corporation, and on November 14, 1951, by Mabasa & Company.

After trial wherein plaintiff presented evidence in his behalf, but none in behalf of intervenors, the court rendered decision dismissing plaintiff's complaint as well as those filed by the intervenors.

On March 31, 1954, counsel for plaintiff filed a notice of appeal, appeal bond, and record on appeal in behalf only of plaintiff even if they also represent the intervenors, which in due time were approved, the Court instructing its clerk to forward the record on appeal to the Supreme Court together with all the evidence presented in the case. This instruction was actually complied with.

On August 31, 1954, the Deputy Clerk of the Supreme Court notified counsel of plaintiff that the record as well as the evidence have already been received and that they should file their brief within 45 days from receipt of the notice.

On November 2, 1954, counsel filed their brief for appellants.

On November 6, 1954, or 7 months after the judgment had become final as against the intervenors, and 4 days after counsel for appellants had submitted the latter's brief, counsel for intervenors filed with the Supreme Court a petition for correction of the record on appeal in order to enable them to insert therein the names of the intervenors as appellants, the petition being based, among others, on the ground that the omission of the names of the intervenors in said record on appeal was due to the mistake of the typist who prepared it while the attorney in charge was on the petition is opposed by counsel for defendant, contending that the same would serve no purpose, whatsoever considering that the intervenors had not presented any evidence in support of their claim, aside from the fact that the alleged absence of the attorney of the intervenors cannot constitute a justification for the alleged omission of the intervenors as appellants.

On November 12, 1954, the Court denied the petition. Counsel intervenors moved for a reconsideration of the order, but the same was denied.

On November 19, 1954, counsel for intervenors filed with the lower court a petition for relief under Rule 38 of the Rules of Court, wherein he reiterated the same grounds they alleged in the petition for correction filed by them in the Supreme Court, which petition was denied on November 27, 1954, for having been filed outside the reglementary period fixed in said Rule 38. Counsel filed a motion for reconsideration, which was again denied, the Court stating that "no judgment or order has been rendered, nor any other proceeding taken by this Court on the right of the intervenors to appeal."

On December 20, 1954, counsel filed once more a motion to amend the record on appeal based on grounds identical with those alleged in the petition for correction filed before the Supreme Court.

On December 27, 1954, the lower court denied the motion.

On January 6, 1955, counsel filed a petition for relief from this last order entered on December 27, 1954, to which counsel for defendant filed an opposition.

On February 5, 1955, hearing was had on both the petition for relief and the opposition, and on February 9, 1955, the petition was denied on the ground that the case is already before the Supreme Court on appeal

To begin with, the only remedy which appellants now seek in this appeal is the inclusion of the intervenors as appellants in the appeal from the decision rendered in the main case, but this remedy has already been denied twice by this Court, first, in its resolution of November 12, 1954 denying their petition for correction of the record on appeal, and, second, in denying their motion for reconsideration of said resolution. It should be noted that the grounds relied upon in this appeal are the same grounds alleged in said petition for correction.In the second place, the intervenors have no right or reason to appeal from the decision in the main case, it appearing that they did not introduce any evidence during the trial in support of their complaint, which shows that their appeal would be merely pro-forma. And, in any event, they made the attempt to amend the record on appeal seven (7) months after the decision had become final against them.In the third place, the intervenors have no right or reason to file a petition for relief under Rule 38 of the Rules of Court from the order of the lower court issued on December 27, 1954, for the reason that the same was entered upon a motion filed by them. Indeed they cannot reasonably assert that the order was entered against them through fraud, accident, mistake, or negligence. The fraud mentioned in Rule 38 is the fraud committed by the adverse party and certainly the same cannot be attributed to the Court.

Finally, it appears that the main case has already been decided by this Court on the merits on October 31, 1956, reversing the decision of the lower court and awarding damages to plaintiff, which apparently is the very purpose which the intervenors seek to accomplish in joining the appeal as co-appellants. This appeal, therefore, has already become moot.

Wherefore, the order appealed from is affirmed, with costs against appellants.

0 notes

Text

United States of America, Plaintiff-appellee, v. Jessica Durham, Defendant-appellant, 464 F.3d 976 (9th Cir. 2006) :: Justia

0 notes