#Raquel Stecher

Text

The Visual Mastery of RUN LOLA RUN (’98) By Raquel Stecher

Half the fun of watching German director Tom Tykwer’s thriller RUN LOLA RUN (’98) is reveling in all of the visual details. There is so much to take in from Frank Griebe’s excellent cinematography to the brilliant use of color and objects that enhance the film’s themes. RUN LOLA RUN stars Franka Potente as Lola, a young woman who must secure 100,000 Deutschmarks and deliver the money to her boyfriend Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu), who desperately needs the cash to pay off a violent gangster. Lola has 20 minutes to complete her mission. The film explores three different outcomes as Lola encounters a variety of obstacles along the way.

Let’s first look at the film’s brilliant use of color. Red and yellow are strategically associated with the two lead characters. Lola is presented with the color red. Her hair is dyed bright red, and each of the three-time loops begins with her hanging up a red phone. Red continually appears at various points in her story, whether it’s a bicycle thief wearing a red shirt or her carrying a red bag full of cash. The image of Potente wearing a red wig and running through the streets of Berlin has become the visual symbol of RUN LOLA RUN and usually the first thing that people will remember about the film. Yellow is Manni’s color. He calls Lola from a yellow telephone booth as he contemplates robbing the grocery store across the street, which just happens to be adorned with yellow fixtures and trim.

Red can be seen to symbolize passion but is also represents speed, especially since Lola is moving at such a frantic pace. Yellow is the complete opposite. It symbolizes the tension-filled act of waiting. This can be observed in one particular scene in which workers dressed in yellow hazmat suits carry a large piece of glass from one side of the street to another. They are confronted with a red ambulance driving at a high speed to bring a cardiac patient to the hospital. This scene is played out in each of the three scenarios with a different result. In other scenes, Lola passes a yellow subway tram, a visual reminder that time is passing and Manni is waiting for her.

One of my favorite, and a bit more subtle, use of color in the film is when green is associated with some form of authority. When Lola visits her dad’s bank to ask for money, his office is adorned with green furniture and a large green painting that Lola rips off the wall in anger. In one scenario, policemen driving green and white vehicles and dressed in green uniforms confront Lola and Manni.

Because the film is so focused on time—not only how Lola is pressed for time but also how one small act can change one’s destiny—clocks and watches are important symbols that pop up throughout the film. There is a big ornate clock in Lola’s bedroom, the face of which is taped over with green stickers, which could be seen as a symbol of how time exerts its authority over her. Manni is constantly checking the clock that hangs above the grocery store entrance, Lola shatters the glass clock in her father’s office with her ear-piercing scream and an old lady checks her watch to give Lola the time. In the casino scene, Lola chooses to play the number 20 on the roulette wheel, which plays to the fact that she only has 20 minutes on the clock to finish the job.

Tom Tykwer drew a lot of inspiration from Alfred Hitchcock’s classic thriller VERTIGO (’58). For the casino scene, Tykwer had production designer fill in empty space on the wall by creating a replica of the iconic Carlotta painting from Hitchcock’s film. VERTIGO also inspired the spiral motif that can be seen throughout the film. As Manni calls from the yellow phone booth, the viewer can spot a shop called Spirale in the background complete with a spiraling fixture. When Lola sets out on her mission, she runs down a spiral staircase, presented in the film through animation rather than live-action. As each of the time loops resets, we see Lola and Manni, contemplating life while resting on pillows with a spiral print.

Cinematographer Frank Griebe also employs the sensation of vertigo through many excellent camera shots. Arc shots, in which the camera circles a subject, are used throughout the film. There are lots of tight close-ups, tracking shots, low angle-shots and top-down perspectives, which beautifully demonstrate the heightened emotion and tension felt by the characters. The camera is constantly moving and so is the imagery. In addition to animation, there are black-and-white flashback scenes, stop motion sequences and when time stops for a moment, those scenes are presented with a hazy filter. The bounty of visual symbolism and the film’s frenetic pace make RUN LOLA RUN a highly enjoyable experimental thriller.

#Run Lola Run#TCM imports#foreign film#german film#experimental film#1990s#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

223 notes

·

View notes

Text

Member Reviews: "Wander Darkly"

Member Reviews: “Wander Darkly”

OAFFC members review “Wander Darkly”

Louisa Moore

Ruth Maramis

Raquel Stecher

Rachel Wagner

Katie Carter

Morgan Rojas

Alessandra Rangel

Alyssa Vitale

Danielle Solzman

Arline Ramirez

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

2017: The Year in Old Movies (because measuring it in other ways wouldn't be nearly as pleasant)

The 10 best of what the Siren watched in 2017, presented without preamble, and in alphabetical order. The Siren wishes her patient readers a most happy 2018.

The Big City (Mahanagar; directed by Satyajit Ray, 1963. Viewed on Criterion DVD)

Madhabi Mukherjee's performance instantly became an all-time favorite. It is part of Satyajit Ray's genius that he refuses to make her husband (Anil Chatterjee, half lummox, half mensch) into a villain, instead showing how the man's prejudices give way not only to love of his wife, but common sense.

Bitter Stems (Los Tallos Amargos; directed by Fernando Ayala, 1956. Viewed at Metrograph)

The Siren thinks this may be the noirest noir of them all. The movie weaves together guilt and ambivalence over Argentina's history in World War II with the hero's (Carlos Cores) own psychological unraveling. Magnificent cinematography by the Chilean Ricardo Younis. Do read Raquel Stecher's post on the film's restoration; you will see how close we came to losing this beauty forever. The Siren was so impressed that she donated to the Film Noir Foundation as thanks.

The Glass Tower (Der gläserne Turm, directed by Harald Braun, 1957. Viewed during Film Society of Lincoln Center's series The Lost Years of German Cinema: 1949–1963.)

A classic women's picture about the emotional abuse inflicted on a former actress (Lilli Palmer) by a secretly psychotic tycoon husband (O.E. Hasse). You'd know this film influenced Rainer Werner Fassbinder even if the program notes never said so. The Siren loved the way it suddenly became almost an Agatha Christie mystery, loved the design (by Walter Haag) that envisions the couple's life as a series of elegant glass-walled prison cells. The plot resembles Under Capricorn, but the film plays out to its resolution in a much more satisfying way. (Bosley Crowther's review is possibly the most sexist thing he ever wrote, which is saying something.)

I'll Be Seeing You (directed by William Dieterle, 1945. Viewed on Kino Classics DVD).

Somehow the Siren had missed this delicate wartime romance, which boasts one of Ginger Rogers' most heartfelt and touching performances. As her character and that of Joseph Cotten gradually fall in love, you realize you are watching two psychically wounded people trying to heal. The Siren much prefers this to the better-known Love Letters (same year, same director), which has a torpid screenplay by Ayn Rand; I'll Be Seeing You has a screenplay by Marion Parsonnet, whose credits include Gilda. The Siren saw I'll Be Seeing You while researching her video essay on Ginger Rogers' dramatic roles, which will be included in Arrow Films' Blu-Ray release of Magnificent Doll in February 2018.

Le Trou (The Hole; directed by Jacques Becker, 1960. Viewed at Film Forum's run of the 4K digital restoration.)

The Siren has a new favorite prison movie. And while this may surprise you, the Siren tends to like prison movies. The late-movie payoff is one that many Hollywood directors would sell a kidney to come up with.

Paris Frills (Falbalas; directed by Jacques Becker, 1945. Viewed on MUBI.)

It's a pity this isn't widely available, as it makes a terrific companion piece to Paul Thomas Anderson's Phantom Thread. The Siren would love to know if Anderson saw it. Paris Frills also concerns an egotistical couturier (Raymond Rouleau), whose atelier is also in a palatial townhouse, and who also runs roughshod over the people around him, with much different consequences. Becker is more concerned than PTA with the daily labor of “les petits mains” and with suggesting all the lives beyond those of his leads. The Siren's favorite scene involved the couturier, deep in a selfish funk about a love affair, being told off by Solange (Gabrielle Dorziat), his equivalent of Phantom Thread's Cyril: “I don't give a damn about her. She has time for sentimental complications, where here there are 300 who can't be permitted that, and who you are going to put out in the street.” (Note for the Siren's fellow lovers of fashion history: The gowns were by Rochas.)

Roses Bloom on the Moorland (Rosen blühen auf dem Heidegrab; directed by Hans H. König, 1952. Viewed as part of the FSLC Lost Years series.)

The Siren's surprise of the year. One alternate title is Rape on the Moorland, which didn't exactly sound like her sort of thing, and she saw it only because it was screening at a rare moment that found her in the Walter Reade neighborhood. The film turned out to be a unique combination of Universal horror movie and rural romance, with Ruth Niehaus splendid as the death-haunted peasant heroine, and Hermann Schomberg storming through his scenes as the bestial villain. König makes exquisite use of the windswept, Bronte-esque setting, but what really sold the Siren was the denouement, with its unexpected warmth and humanity.

Ruthless (directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, 1948. Viewed as part of the MoMA series “Poverty Row.”)

Written about in the Siren's roundup of this series at the Village Voice.

The Spy in Black (directed by Michael Powell, screenplay by Emeric Pressburger, 1939. Viewed on MUBI)

Yes yes, everybody else already got to this one; better late than never, my friends. Terrific-looking BFI restoration. Conrad Veidt has a great doomed romantic part even though he's nominally the villain. Excellent location work in the Orkneys. A coolly intriguing performance by Valerie Hobson, who ordinarily doesn't excite the Siren.

Tonka of the Gallows (Tonka Sibenice, directed by Karel Anton, 1930. Viewed as part of MoMA's series “Ecstasy and Irony: Czech Cinema, 1927–1943.”)

The Siren wrote her heart out about this one at her Film Comment blog.

Honorable mention, among many others seen and enjoyed:

I Knew Her Well (Antonio Pietrangeli, Italy 1965)

Kristian (Martin Fric, Czechoslovakia, 1939)

Happy Journey (Otakar Vavra, Czechoslovakia 1943)

False Faces (Lowell Sherman, U.S. 1932)

Sword of Doom (Kihachi Okamoto, Japan 1966)

Black Gravel (Helmut Kautner, Germany, 1961. Note: This one is not for dog lovers.)

###

What follows is a roundup of some of the work that the Siren did elsewhere this year, aside from those already mentioned above.

Booklet essay for the Masters of Cinema Blu-Ray of Cover Girl (a stunning restoration, by the way).

Booklet essay for Criterion's Blu-Ray of His Girl Friday.

Booklet essay for Criterion's Blu-Ray of The Philadelphia Story.

Booklet essay for Film Movement's Blu-Ray box set of the Sissi movies, starring Romy Schneider.

For the Village Voice, a write-up of "Hank and Jim," a series at Film Forum linked to Scott Eyman's wonderful book about the deep, lifelong friendship between Henry Fonda and James Stewart.

Also for the Voice, an essay about the William Wyler series that ran at the sparkling new Quad Cinema.

"What Makes Lubitsch Lubitsch?" at the Voice, a chance to ramble on about the master, via the Film Forum's near-complete retrospective.

An essay on the magnificent Marseille Trilogy, again at the Voice.

For her blog at Film Comment, in addition to her essay on Tonka, the Siren wrote on

Michèle Morgan

Beat the Devil

The Stranger

The Last Man on Earth & It's Great to Be Alive

The “Roman Hollywood” series at Film Forum; this blog post includes the Siren holding forth briefly on her love for Three Coins in the Fountain.

0 notes

Text

Julien Temple Musicals: ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS (’86) and EARTH GIRLS ARE EASY (’88) By Raquel Stecher

Director Julien Temple has built his filmmaking career showcasing creative types. Musicians are his forte, although he’s also made films about poets, filmmakers and other artists. Best known for his music videos, he’s directed artists such as the Rolling Stones, Depeche Mode, Whitney Houston, Janet Jackson, Billy Idol, Van Halen and Paul McCartney. He became interested in filmmaking when he discovered the work of French filmmaker Jean Vigo, whom he would later direct a biopic about. He began working alongside the Sex Pistols and made his debut feature film The Great Rock ’N’ Roll Swindle (’80) about the band’s tumultuous break-up.

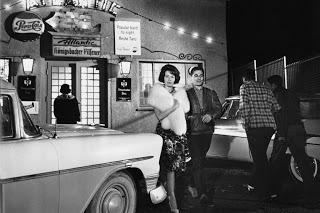

Temple had a front row seat at a time when music was revolutionizing culture but was also interested in how the music of the past influenced the present. Among his films are two outliers, a pair of films inspired by Temple’s love of Hollywood musicals: ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS (’86) and EARTH GIRLS ARE EASY (’88). An homage to the early days of rock ‘n’ roll, ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS was an adaptation of Colin MacInnes’ 1959 novel. Set in 1958 during the time of the Notting Hill race riots, it explores the cultural revolution of the time, when jazz was falling out of favor, rock ‘n’ roll was making a scene and teenagers were being recognized as a major influence on popular culture. Eddie O’Connell stars as Colin, a photographer who falls in love with fashion designer Crepe Suzette (Patsy Kensit) and gets caught up in the local music scene. The film features performances by Sade and Davide Bowie, two musicians Temple had previous directed music videos for.

According to the website Supajam, ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS was at the time “the most expensive British film ever made.” When the shooting wrapped, Temple was fired. He had no involvement with the final editing, which was handled by three different editors. The end result was a musical that strayed from Temple’s vision. In an interview, Temple called the production “a half-nightmare, half-dream” and said that he wishes it would have come out differently. The film was a flop and bankrupted British movie studio Goldcrest Film International. Temple goes on to say in his interview with Supajam, “It was strange being accused of destroying the British film industry… for many decades, it seemed to be circling Pluto, but it seems to have made its way a bit closer back towards Earth these days.”

The film caught the eye of Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson. Temple is quoted as saying, “It turned out the Jackson family were fans, particularly Michael and Janet, who used to copy the dance sequences as it played on their cinema screen.” Temple went on to direct two music videos for Janet Jackson. “When I Think of You” pays homage to ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS urban setting and “Alright” is a throwback to the golden era of Hollywood musicals and features cameos by the Nicholas Brothers, Cab Calloway and Cyd Charisse.

When Temple left the UK to work in the US, he made another go at the musical feature film with EARTH GIRLS ARE EASY (’88). This science fiction romantic comedy musical hybrid starred then real-life couple Geena Davis and Jeff Goldblum in their third picture together. Written by Julie Brown, Terrence E. McNally and Charlie Coffey, the story follows California girl Valerie (Geena Davis) who, in the midst of romantic turmoil, is visited by three furry aliens: Jeff Goldblum, Jim Carrey and Damon Wayans. The aliens are given a makeover to best resemble humans and they cause a ruckus in the Valley with their new look.

The movie is chock full of 1980s esthetics and slang, making it a nostalgic delight for anyone who lived through, or just loves, that era. It even includes a cameo by the mysterious lady in pink Angelyne, who was herself a precursor to today’s celebrity influencers. The film also serves as a throwback to 1950s science fiction films like Forbidden Planet (’56) and Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (’56). The trio of aliens learn human behavior and language from watching classics on television like Gun Fury (’53), Rebel Without a Cause (’55) and The Nutty Professor (’63).

Given his newfound reputation, Temple had a difficult time finding a studio or production company for the film. Warner Bros., MGM, 20th Century-Fox and New World Pictures all expressed interest but eventually turned it down. It was picked up by De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, which was set to distribute, but they filed for bankruptcy shortly after filming. The movie didn’t make a splash at the time, however it’s gone on to earn the cult classic status it so rightly deserves. EARTH GIRLS ARE EASY served as the inspiration for the Britney Spears and Iggy Azalea music video for “Pretty Girls” released in 2015.

#Earth Girls Are Easy#Julien Temple#1980s#musicals#retro#moder day musical#MTV#music videos#classic hollywood#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oscars of the Past: A Look at Discontinued Categories By Raquel Stecher

The Academy Awards have evolved greatly since that first ceremony was held on May 16th, 1929 in the Blossom Ballroom of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. To quote the late, great Robert Osborne, who himself was the foremost expert on Oscar history, the early days were “a time of great changes everywhere, a dynamic period of transition.” And after the first decade, “the Academy Awards and the Academy itself had become prestigious parts of the film community.” Much of that first decade and beyond saw the Board of Governors and the Academy experimenting with new and shifting categories, establishing a variety of honorary awards and altering the selection process.

There was a time when winners were announced months before the actual ceremonies without nominees, just a sole winner and honorable mentions and when write-in nominations were allowed and the Board of Governors hand-selected winners without input from the Academy. The awards have changed over time and the process has been fine-tuned. While some categories have lasted to this day, many have been discontinued, relegated to the history books as anomalies of Oscar’s past. Let’s take a look at some of the most notable discontinued categories.

BEST UNIQUE AND ARTISTIC PICTURE:

There were 12 award categories presented at the very first Academy Awards ceremony. A few of these were one-shot deals never to appear again. Best Picture, as it is known today, was split into two categories: Outstanding Picture and Unique and Artistic Picture. While WINGS (’27) is generally considered to be the first Best Picture winner, SUNRISE (’27) won Best Unique and Artistic Picture, a recognition no other film has earned since.

BEST DIRECTING, COMEDY PICTURE & DRAMATIC PICTURE:

That same year, the Best Director category was split into two: Comedy Picture and Dramatic Picture. There were no nominees, just one winner and one or two honorees. Frank Borzage won the only Best Directing, Dramatic Picture Oscar for 7TH HEAVEN (’27) and Lewis Milestone won Best Directing, Comedy Picture for TWO ARABIAN KNIGHTS (’27). Charlie Chaplin was to be nominated for directing THE CIRCUS (’28), but according to Robert Osborne, the Academy decided to give him a special award instead in recognition for directing, writing, producing and acting in the film. The Academy Board of Judges, as it was known at the time, sang Chaplin’s praises and in a letter wrote to him saying, “the collective accomplishments thus displayed place you in a class by yourself.”

BEST ENGINEERING EFFECTS:

Special effects artist Roy Pomeroy won the first and only Academy Award for Best Engineering Effects for his work on WINGS (’27). Ralph Hammeras and Nugent Slaughter, the latter of whom was being recognized for his work on THE JAZZ SINGER (’27), received honorable mentions. This award disappeared until 1938 when it was given new life as the Best Special Effects Oscar. It split into two sub-categories: Photographic and Sound. In the mid-1940s, it was changed again to Visual and Audible. By 1963, the Academy decided to present the awards as Best Visual Effects and Best Sound Editing. While Visual Effects is still an active category, Best Sound Editing was merged with Best Sound Mixing to become simply Best Sound.

JUVENILE OSCAR:

From 1935 to 1961, the Academy presented miniature Oscar statuettes to juvenile actors in recognition for their outstanding contributions to film. There were 12 total recipients at 10 different award ceremonies. The first was Shirley Temple who at 6 years old was presented the statuette by Irvin S. Cobb. He declared “When Santa Claus brought you down Creation’s chimney, he brought the loveliest Christmas present that has ever been given to the world.” Other recipients included Deanna Durbin, Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, Margaret O’Brien, Peggy Ann Garner, Claude Jarman Jr., Bobby Driscoll and others. Both Garland and O’Brien’s Juvenile Oscars were stolen and the Academy replaced them with new statuettes. There were only 14 miniature statuettes ever made, making this one of the rarest Oscars in history not only because of its size but how few were made. The award wasn’t presented every year and was fairly inconsistent. The last to win was POLLYANNA (’60) star Hayley Mills. Shirley Temple presented the final award and Annette Funicello accepted it on Mills’ behalf. The award was retired and actors under the age of 18 were eventually recognized in the other acting categories.

BEST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR:

This is by far the strangest and least consistent of the discontinued categories. At the 6th Academy Awards in 1934, a whopping 18 assistant directors were nominated for this new category. Out of the 18 nominees, there were 7 winners each representing one of the major studios. The nominations were not tied to a specific movie, but rather served as recognition for work completed in 1932 and 1933. The first winners included: Charles Barton (Paramount), Scott Beal (Universal), Charles Dorian (MGM), Fred Fox (United Artists), Gordon Hollingshead (Warner Bros.), Dewey Starkey (RKO) and William Tummel (Fox). The category was presented at the next four Academy Awards but with only a few nominees and just one winner. After 1938, the Academy retired the category, choosing to focus on Best Director.

BEST DANCE DIRECTION:

Choreographers enjoyed some recognition during the hey-day of 1930s musical with the Best Dance Direction Oscar. This category was presented from 1936 to 1938. At the 8th Academy Awards, seven choreographers were nominated, each for two different musical numbers, not necessarily in the same film. Dave Gould won for his dance numbers in BROADWAY MELODY OF 1936 (’35) and FOLIES BERGERES DE PARIS (’35). The following two years, seven choreographers were nominated, each for just one dance number. This category was short-lived and did not make a comeback in 1939.

#Oscars#academy awards#2021#1929#AMPAS#old hollywood#classic movies#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don’t Let the Subtitles Scare You: The History of the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar By Raquel Stecher

The Academy Awards has a long and complicated history of recognizing international films. The Best Foreign Language Film category, now the Best International Feature Film, was an attempt to rectify this and give international filmmakers, with films in languages other than English, an opportunity to earn the coveted Oscar statuette.

It all started with Conrad Nagel. He was one of the founding members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). When he and 35 fellow members of the film industry convened at the Ambassador Hotel in 1927 to discuss the path forward for the organization, Nagel suggested that “International” be included in the title. According to writer Michael S. Barrett, “he was persuaded to drop the International and for many years AMPAS appeared specifically dedicated to American films.”

Prior to 1957, foreign language films struggled to get noticed by the Academy. Jean Renoir’s GRAND ILLUSION (’37) was the first international film nominated for Best Picture. Other films were recognized in categories such as Best Writing and Best Art Direction, but these instances were few and far between. Then came WWII, which had a major impact on international filmmaking. Barrett writes, “out of the ashes of war came a crop of innovative filmmakers champing at the bit to do something creative and useful, and this was shown in the new styles of moviemaking under which they labored, fervently promoted and eventually attained undying fame.” American audiences were drawn to Italian Neorealism, Japanese Jidaigeki and later the French New Wave as exciting and new forms of cinema.

For the 20th Academy Awards in 1948, AMPAS’ Board of Governors created an honorary award for Best Foreign Language Film. At first it was not a competitive award. There were no nominees, the Board would select just one film and while the honorary award was presented during the ceremony, news of the winner would often be announced before the ceremony. From 1948 to 1956, eight foreign language films were awarded, including SHOESHINE (’46) and BICYCLE THIEVES (’48) from Italy; MONSIEUR VINCENT (’47), THE WALLS OF MALAPAGA (’49) and FORBIDDEN GAMES (’52) from France; and RASHOMON (’50), GATE OF HELL (’53) and SAMURAI I: MUSASHI MIYAMOTO (’54) from Japan. Interesting to note that they completely skipped the award in 1954 and no explanation was given as to why.

The special achievement award morphed into a competitive one in 1957. Countries could submit one film for competition as long as they fit the Academy’s strict criteria. Films had to be longer than 40 minutes to be considered feature length, from a country outside the US and include more than 50% non-English dialogue. But of course, to be considered, English-language subtitles were necessary. Only the country’s officially designated representative could submit a film for consideration. The Academy would then select five nominees from the submissions and members voted on secret ballots. The rules shifted over time. Since 2006, it’s no longer required that the language spoken in the film be the most commonly spoken language of that country. Also rules about both public and private Academy screenings in the Los Angeles area have changed and now a film no longer has to be screened in the U.S. to qualify. Technically, the winner of the Oscar is the country of origin and not the director or producer, however they are usually the ones to accept the award at the ceremony.

The first Best Foreign Language Film was presented by AMPAS president George Seaton to Italy for Federico Fellini’s LA STRADA (’54). The award was accepted by producer Dino De Laurentiis. Early winners included France’s BLACK ORPHEUS (’59) and MON UNCLE (’58), Sweden’s THE VIRGIN SPRING (’60) and Italy’s NIGHTS OF CABIRIA (’57) and 8-1/2 (’63). Some critically acclaimed foreign films were overlooked because they either weren’t submitted by their native country or were disqualified for some reason or another. These included major films like LA DOLCE VITA (’60) and THE SEVENTH SEAL (’57). And if a foreign film was screened in the US, it had a better chance at winning the coveted prize. Once a foreign language film won the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, it would be screened in the U.S., qualifying it for other competitive categories, like Best Director, Best Writing, Best Costume Design, etc. the following year.

Presenters for this category have almost always been either actors or the current AMPAS president. Jack Valenti, longtime president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) holds the record for most presentations for this category. Having recently watched all of the televised presentations and acceptance speeches on the Academy’s YouTube channel, I couldn’t help but notice the consistent trend of flowery speeches about the universal language of cinema. A few presenters stood out. Stars like Jane Fonda and Anthony Quinn openly criticized the use of the word “foreign” in the category. It’s always been required that the winner deliver their speech in English. As acceptance speeches grew longer over time, many filmmakers, especially from war torn nations, would seize the moment and the platform to deliver a poignant message.

There are three acceptance speeches that stand out to me. Perhaps the most famous one is from 1999 when actor/director Roberto Benigni accepted the award for LIFE IS BEAUTIFUL (’98). Benigni leapt from his seat, walked over guests, hopped up the steps and gave presenter Sophia Loren the biggest hug. His speech was incredibly emotional and there wasn’t a dry eye in the house by the end of it. My second favorite was delivered by director Alfonso Cuaron for his film ROMA (2018). While the Academy hasn’t publicly admitted this, I think Cuaron’s speech, in which he very gently criticizes the category and thanks the nominees who “have proven that we are part of the same ocean,” influenced change. The following year the Academy quickly pivoted and changed the category to Best International Feature Film. Dutch director Fons Rademakers whose film THE ASSAULT (’86) won in 1987, delivers my favorite speech. In it, he speaks to the general aversion to foreign language films by saying “This Foreign Language Oscar has a request... please don't let subtitles scare you off as much as they seem to do from time to time.” Take his advice. Watch more international films!

#International films#Academy Awards#Oscars#best foreign language film#Best Oscar#history#tcm#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dean Stockwell, Reluctant Child Star By Raquel Stecher

Born in Hollywood to a show business family, it seemed like Dean Stockwell was destined to become a movie star, but Stockwell stumbled into the industry simply by chance. In 1942, his mother Elizabeth “Betty” Stockwell, a vaudeville performer, and his father Harry, a stage singer best known for being the voice of the Prince in SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS (’37), heard of a casting call for children. Dean and his older brother Guy auditioned for roles in a stage performance of The Innocent Voyage. Though only landing a small part with just two lines, it was all that was needed to catch the eye of an MGM talent scout. Before he knew it, the nine-year-old Stockwell had a seven-year contract with the studio. He was exactly what they were looking for. With his mop of curly hair and prominent pout, he gave off just the right combination of innocence and petulance that would make him a perfect fit to play orphans and spoiled rich kids in a variety of MGM productions.

Dean Stockwell was off to a roaring start with plum roles in big productions like ANCHOR’S AWEIGH (’45), THE GREEN YEARS (’46), GENTLEMAN’S AGREEMENT (’47) and SONG OF THE THIN MAN (’47). He held his own with big stars like Gregory Peck, Gene Kelly, William Powell, Myrna Loy, Greer Garson, Robert Ryan and Lionel Barrymore and other child stars Peggy Ann Garner, Darryl Hickman and Margaret O’Brien.

He was an incredible asset to MGM. Stockwell could be counted on to cry in front of the camera, sometimes coaxed by a director who encouraged him to imagine a dying pet. Even with that, Stockwell developed a reputation as an intelligent and sensitive young boy who needed little rehearsal and minimal direction. They called him “One-Take Stockwell.” In interviews years later, he recalled “I had photographic memory when I was a kid. I still can memorize lines very easily.” Stockwell was a natural and the parts just kept coming. When he wasn’t working for MGM on films, his home studio would loan him out to RKO, 20th Century-Fox and Universal.

But Being a child actor took a toll on Stockwell. The studio system could be cruel to child stars and Stockwell often bore the brunt of it. In an interview Stockwell said, “[as a] child star… I didn't have much privacy and I was working all the time. I couldn't be where I wanted to be; I couldn't play; so I needed to find anonymity, to just disappear.” He often worked 10-hour days six days a week, which included 3 hours of learning in the Little Red Schoolhouse on the MGM lot. He had to keep going for two reasons: 1.) his ironclad contract with MGM and 2.) a family to support, now that Betty was raising Dean and his brother as a single mom. Stockwell desperately wanted to be an average kid. He loved playing sports, dreamed of going to public school and loved spending time with his dogs, Thug and Thief. On the set of STARS IN MY CROWN (’50), he even declared to producer William Wright “I wish you’d fire me, so I wouldn’t have to work!”

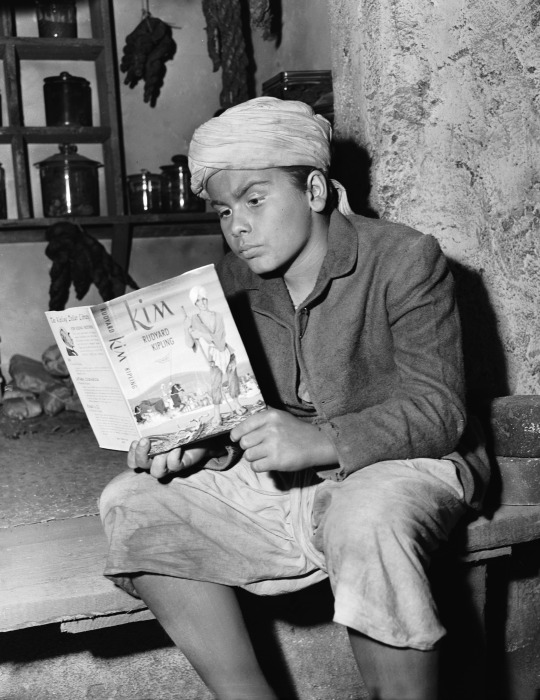

During his seven-year contract with MGM, he made nearly 20 films for his home studio and others while on loan out. For the most part, Stockwell was miserable working as a child actor but there were two productions that he particularly loved. One was the anti-war drama THE BOY WITH THE GREEN HAIR (‘48) produced by RKO. In it, he plays a war orphan whose hair suddenly turns green, making him stand out from the locals. Stockwell identified with his character’s desire to fit in and the film’s pacifist message. When Howard Hughes tried to get him to deliver a pro-war statement, Stockwell stood up to the studio tycoon and refused. A few years later, he starred alongside Errol Flynn in KIM (’51), an adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s classic story. Flynn became a father figure of sorts to young Stockwell and the two got on like a house on fire.

As Dean got older, he entered into what he called the “awkward age.” He later said, “[MGM] couldn't see how they were going to cast me now that I was turning 17. So they let me out of it and I just took off.” Dean finished high school, attended UC Berkeley and dropped out before finishing his first year. He didn’t know what he wanted but he did know he no longer wanted to be Dean Stockwell the child star. He donned a new identity, Rudy Stocker, and lived in anonymity as a day laborer. He made his way back to acting after a few years. Had it not been for his escape from Hollywood, a time period Stockwell referred to as “an education in living”, as well as the support of his mother, he might have gone down the wrong path as other child actors have done. Instead Dean Stockwell made an excellent comeback in the Leopold and Lobb inspired murder drama COMPULSION (’59). Reflecting on his past, Stockwell said “I have to know if people want me – for myself.” He would make several comebacks throughout his acting career and he learned an important lesson from his days as a child actor: be true to yourself.

youtube

#Dean Stockwell#child stars#actors#old Hollywood#studio system#MGM#acting#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sammy Davis Jr.: Ambition and Generosity By Raquel Stecher

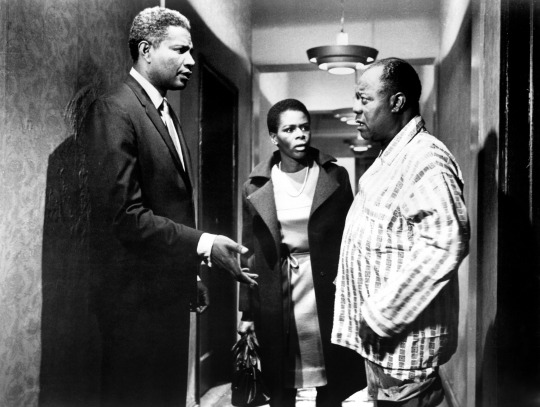

Sometimes a movie is more important for what it did than for what it is. This is the case for A MAN CALLED ADAM (’66), a drama starring Sammy Davis Jr. as a self-destructive jazz musician who is so tormented by past traumas that he lashes out at those who support him. A MAN CALLED ADAM was an opportunity for Davis to sink his teeth into a more serious role, to launch his production company and to support those both in his inner circle as well as up-and-coming young Black talent. In his book Hollywood Black, film historian Donald Bogle writes about the era: “the very nature of film production was gradually questioned. Who tells the stories of Black Americans on-screen? What’s being said? What’s not being said? Though major African American filmmakers were still absent at the Hollywood studios, some new faces worked in significant ways behind the scenes. A sign of the shift was 1966’s A MAN CALLED ADAM…”

By the mid 1960s, Davis was at the top of his game as a multi-talented entertainer and one of the faces of the Rat Pack. When he wasn’t performing in Las Vegas, he was making films with fellow Rat Packers, hosting The Sammy Davis, Jr. Show on TV and performing on Broadway. What was missing for him was being taken seriously as a film actor. He craved the type of character that was devoid of stereotypes and not an easy target for white characters. He found this in the title role of Adam Johnson, a fictional character created by husband-and-wife screenwriting team Lester and Tina Pine. The script was originally intended for Nat King Cole who took an interest in the project but knew he didn’t have the acting chops to play the role. According to Cole biographer Will Friedwald, Cole was intrigued by the authenticity of the story and how it was an opportunity to make what he referred to as a real jazz movie. Cole passed away at the age of 45 before he had the opportunity to make the film, albeit in what would have been a supporting role.

The script then found its way into the hands of Ike Jones, a young Black producer who had turned down a lucrative offer to play professional football in order to follow his dream of working in the movies. Jones had been an assistant director on the THE JOE LOUIS STORY (’53) and found work as an executive for Burt Lancaster’s Hecht-Hill-Lancaster Company, Nat King Cole’s Kell-Cole Productions and Harry Belafonte’s HarBel Productions. Independent film productions were all the rage at the time as it gave actors more artistic freedom to play the parts that they felt the studios were withholding from them. Davis had started his own company, Trace-Mark Productions, named after his children Tracey and Mark, and this script would provide the material for its very first film. Davis made history when he hired Ike Jones as the first Black producer for a major Hollywood production.

In taking on this project, I imagine that Davis was inspired by Frank Sinatra, the leader of the Rat Pack and someone whom he greatly admired, despite their often-contentious relationship. Sinatra had turned his career around a decade earlier with dramatic performances in FROM HERE TO ETERNITY (’53) and THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN ARM (’55). Sinatra was particularly proud of his performance in the latter, and I can see how the title might have influenced Davis’ decision to change ADAM to A MAN CALLED ADAM.

Davis used this production as an opportunity to help new talent in the business, especially Black performers. Cicely Tyson, who plays an activist and the main love interest, Claudia, was making a name for herself in television and film but was still a few years away from her breakout performances in THE HEART IS A LONELY HUNTER (’68) and SOUNDER (’72). As Bogle points out, Tyson stood out with her sensitive performance and her unique brand of beauty which challenged the standards of the time. A MAN CALLED ADAM debuted new talent including Johnny Brown, Lola Falana and Ja’net DuBois. Brown had impressed Davis with his impressions and acting chops. In the film, Brown essentially plays a Ray Charles type figure. Lola Falana was an up-and-coming dancer who had made an appearance on Davis’ variety show and would soon tour with Davis in Europe. Also appearing as extras are Morgan Freeman and George Kirby, who can be spotted in a party scene in the latter half of the movie.

Davis also used this production as an opportunity to help those in his inner circle. Black actor and civil rights activist Ossie Davis had landed in some hot water with his public criticism of the Vietnam War. Sammy supported his friend by threatening to leave the studio that tried to oust Ossie and by hiring him for a supporting role in his new production. Davis even gave his own mother Elvera, who had been working as a bartender in Atlantic City, a bit part. Other members of the crew included white director Leo Penn who had previously been blacklisted and had directed Davis on an episode of the Ben Casey series. Davis also extended a hand by hiring on fellow Rat Packer Peter Lawford as well as Frank Sinatra’s son Frank Sinatra Jr. in supporting roles.

The casting of A MAN CALLED ADAM demonstrates both Sammy Davis Jr.’s generosity and his support for new and struggling talent. He was clearly aware of how the industry was driven by a who-you-know mentality. By opening doors for others, he created a pathway for talent to bloom and blossom in an industry that desperately needed change, especially in the ways it represented Black characters.

#Sammy Davis Jr#A Man Called Adam#Black producers#classic indie#Harry Belafonte#Cicely Tyson#Ossie Davis#Rat Pack#Frank Sinatra#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pedro Almodóvar: The Classic Movie Fan By Raquel Stecher

Spanish director Pedro Almodóvar is one of the most celebrated filmmakers working today. His bold films feature quirky characters, vibrant colors, especially shades of red, and offer viewers frank explorations on sexuality, identity, family and relationships. Almodóvar is involved in every aspect of the filmmaking process including writing, directing and casting, and he has input in other aspects including set design, costumes and cinematography. His films are uniquely his vision.

Almodóvar has a lifelong love of film and it shows in his work. In his early days he was influenced by the work of the great Spanish directors Luis Buñuel and Luis García Berlanga. He also drew inspiration from directors like Billy Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Elia Kazan, Fritz Lang, Ingmar Bergman, Michael Antonini, Francois Truffaut and many others. Almodóvar was mostly self-taught and learned filmmaking from watching the masters. The characters in Almodóvar’s films are extensions of himself; they too are moviegoers who love and appreciate the art form. You can see this in subtle clues in his films, like posters on a wall, DVDs stacked on a table or what the characters are watching on television. Then there are the more obvious examples including classic film clips and homages to iconic movie scenes. And for classic movie fans, watching Almodóvar’s films can be like a fun treasure hunt seeking out all the references to familiar favorites.

In Almodóvar’s early works, a well-placed poster can illuminate an aspect of the character’s personality. For example, in KIKA (’93), a deranged psychologist has classic horror movie posters in her apartment including from THE SADIST (’63) and CIRCUS OF HORRORS (’60). Almodóvar was particularly inspired by classic movies with strong female leads. In his early film PEPI, LUCI, BOM AND OTHER GIRLS LIKE MOM (’80), Almodóvar took inspiration from George Cukor’s THE WOMEN (’39) to tell the story of a trio of women living during the cultural revolution of Madrid called La Movida Madrileña.

ALL ABOUT MY MOTHER‘s (’99) title comes from Bette Davis’ comeback classic ALL ABOUT EVE (’50). In the very first scene, a mother and son sit down to watch the film on television. It’s announced in Spanish as “Eve Unveiled,” something the characters discuss because the title should have been “Todo Sobre Eva”. Later, in the film, we see a Davis poster pinned to a dressing room wall and the film ends with a note celebrating actresses and mothers and noting Davis, Gena Rowlands and Romy Schneider. Classic actresses come to the forefront in BROKEN EMBRACES (2009) where Penelope Cruz is the mistress of a wealthy magnate who dreams of becoming a star. When she gets the plum role of lead actress in a feature film, she’s made over several times to look like Goldie Hawn, Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn.

One of Almodóvar’s most celebrated works, WOMEN ON THE VERGE OF A NERVOUS BREAKDOWN (’88), starts with a scene from JOHNNY GUITAR (’54). Two actors are dubbing Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden in Spanish. We learn that the actors, much like Hayden and Crawford in the film, have a tempestuous relationship. Almodóvar’s film got the attention of American audiences and earned a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film. And perhaps more importantly for Almodóvar, it got him a meeting with his hero Billy Wilder who greatly admired the up-and-coming filmmaker’s work. In this film, Almodóvar also pays tribute to one of his favorite directors: Alfred Hitchcock. In one scene, Carmen Maura sits on a park bench and watches a young woman dancing alone in her apartment, a clear reference to Miss Torso from REAR WINDOW (’54). In KIKA, a voyeur with a long-focus lens witnesses a crime being perpetrated against a woman, much like Jimmy Stewart in Hitchcock’s film.

As Almodóvar’s films became more and more autobiographical, he began to add more clues to his lifelong love of cinema. Characters are often seen watching some of Almodóvar’s favorite films on television. In VOLVER (2006), a dead mother returns to her community and watches BELLISSIMA (’51) while caring for a dying woman. In TIE ME UP! TIE ME DOWN! (’89), Antonio Banderas kidnaps Victoria Abril, ties her up and leaves her to watch NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (’68). Movie watching becomes an important plot device in later films. In BAD EDUCATION (2004), Gael Garcia Bernal and Lluis Homar have just committed a crime and attend a film noir festival to decompress and create an alibi for their whereabouts. As they leave the cinema, Homar says, “it’s as if the films were talking about us” and the camera pauses on three posters: DOUBLE INDEMNITY (’44), LA BETE HUMAINE (’38) and THERESE RAQUIN (’53).

In his most autobiographical film to date, PAIN AND GLORY (2019), Almodóvar shares his journey in becoming a filmmaker, his early love of classic film and his struggles with the creative process. The young Salvador, played by Asier Flores, collects classic film star cards in a beautiful scrapbook. His collection includes Betty Hutton, Piper Laurie, Loretta Young, Donna Reed, Kirk Douglas, Tyrone Power and Robert Taylor. In the present, filmmaker Salvador, played by Antonio Banderas, is working on a screenplay called La Addiccion. His actor Alberto plays out the scenes, where he projects SPLENDOR IN THE GRASS (’61) and NIAGARA (’53) on a screen and shares a soliloquy about watching water-themed movies as a child. And at the cinema where the filmmaker’s latest film is being screened, the audience can spot a poster of THE EXECUTIONER (’63), which is one of Almodovar’s favorite films.

There is something gratifying about watching a movie made by someone who truly loves and appreciates classic film. Pedro Almodóvar’s work is incredibly contemporary but extends an invitation to those of us who love the old in order to embrace the new.

#pedro almodóvar#director#antonio banderas#classic movies#old Hollywood#Bette Davis#Joan Crawford#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Spanish cinema#hispanic representation#latinx cinema#raquel stecher

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

MADCHEN IN UNIFORM (’31): The First Lesbian Feature Film By Raquel Stecher

Director Leontine Sagan’s MADCHEN IN UNIFORM (’31) wasn’t the first movie that featured lesbian characters but it was certainly a notable one. This German film came during a time between WWI and WWII when there was a thriving gay subculture in parts of Europe. Movies like DIFFERENT FROM THE OTHERS (’19) and MICHAEL (’24) were born out of that era and candidly depicted gay relationships. Marlene Dietrich gave the world the first cinematic lesbian kiss in MOROCCO (’30). PANDORA’S BOX (’29), starring Louise Brooks, featured a lesbian subplot. This was a flourishing time for queer representation and it ended abruptly with the emergence of the Nazi regime.

MADCHEN IN UNIFORM was special in many regards. It’s the first feature film with a solely lesbian theme. It was based on a play written by a woman. It was directed by a woman, with an artistic director credit going to Carl Froelich. And, the cast was completely made up of women. Not a single man can be spotted throughout the whole movie.

Set in a Prussian all-girls boarding school, MADCHEN IN UNIFORM, which translates into “Girls in Uniform,” tells the story of new student Manuela (Hertha Thiele) and her attraction towards her instructor, Fraulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck). The school is run by a strict headmistress, played by Emilia Unda, who extols Prussian virtues of discipline, obedience, restraint and self-denial. In the context of the story, these virtues are seen as old-fashioned and severe, something that the contemporary audience of Germany’s Weimar Republic would have agreed with. The headmistress creates an environment that stifles Manuela and her fellow students who find themselves in a fairly delicate stage of their development. Even though it��s a toned-down version of the original play, Sagan’s film is still a notably frank expression of lesbian romance. There is a kiss between Wieck and Thiele, an exchange of garments, a brief experimentation with gender identity and a passionate declaration of love.

Playwright Christa Winsloe based the story on her own experience at a Prussian boarding school. Writing the play was her way of processing the trauma of her youth. Upon the success of her play, Winsloe moved to Berlin and lived openly as a lesbian. She was once married to a Baron then later became romantically involved with two other women writers, newspaper reporter Dorothy Thompson and Swiss author Simone Gentet.

Winsloe’s play caught the eye of theater producer and actress Leontine Sagan. In her memoir, Sagan recalls MADCHEN IN UNIFORM “was an original play and true to life, but it was technically rough and amateurish in its dramaturgical structure. Nonetheless, I liked this unusual play about girls in a Prussian boarding school and made the author’s acquaintance.” MADCHEN IN UNIFORM would be Sagan’s directorial debut and she would later produce the play for the Duchess Theatre in London.

It was inevitable that changes had to be made to Winsloe’s original story. Overt lesbian themes were dialed back. Artistic director Froelich suggested that the ending be changed from tragedy to something that would be more open-ended. While Winsloe approved of the final film, she still felt a natural possessiveness towards her story. She novelized the film, her way of taking ownership of the story once again, and published MADCHEN IN UNIFORM as a book in 1933.

Upon release, critics and audiences alike raved about the movie. It received glowing reviews. While it was never widely released in the United States, it did ultimately screen in over 1,000 theaters. Andre Sennwald of The New York Times called it a “masterpiece”. Mordaunt Hall of the same publication said in two 1932 reviews “Few motion pictures have been endowed with the magnetic quality of MADCHEN IN UNIFORM… It is a film in which all the characters fasten themselves in one’s mind, not as actors, but as real persons. The performances of all are deserving of the highest praise.” Of course the film met with some opposition. It was “Banned in Boston”, a badge of honor for provocative work. Film producer John Krimsky battled with the Hays Office to get the film approved for distribution.

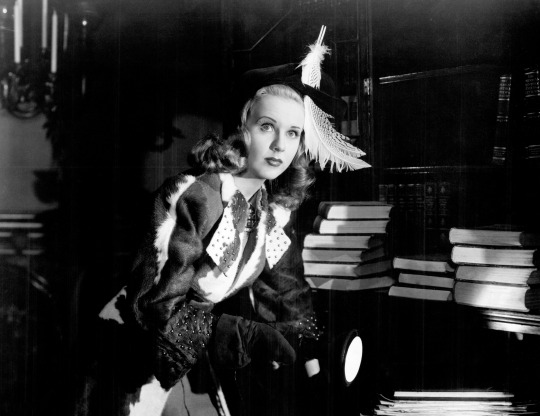

Producer David O. Selznick was so impressed with Sagan’s debut film that he invited her to Hollywood. She made two films there, both were flops, and returned to the theater where she thrived. Actress Dorothea Wieck was also courted by Hollywood. Paramount executives, intrigued by her striking resemblance to MGM star Norma Shearer, put her under contract. Wieck’s Hollywood films were box-office failures. She was booted out of tinseltown and unfairly labeled a Nazi spy. The irony was that Wieck was an outspoken critic of the Nazi regime and refused to act in Nazi propaganda films.

In fact most of the women involved with MADCHEN IN UNIFORM were courted by the Nazis. Although the film was banned in Nazi Germany and many copies were destroyed, Joseph Goebbels himself was a fan and called it a “magnificently directed, exceptionally natural and exciting film art”. Leontine Sagan, actresses Hertha Thiele and Erika Mann all refused offers by the Nazi government to use their talents for propaganda.

After the war, the film languished under censorship but never lost its appeal. It was remade several times including a 1958 film adaptation starring Lilli Palmer and Romy Schneider. It was in a long line of lesbian-themed stories set in all-girl schools, including Colette’s Claudine novels (she wrote the French subtitles for the film), Jacqueline Audry’s OLIVIA (’51) and William Wyler’s THE CHILDREN’S HOUR (’61). MADCHEN IN UNIFORM enjoyed a resurgence of interest in the 1970s finding fans among a growing community of feminists and lesbians with an interest in women directed films. Today it still stands as a seminal lesbian drama that deserves to be studied and appreciated.

#LGBTQ#lesbian representation#lesbian romance#Prussia#war#boarding school#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

542 notes

·

View notes

Text

Claude Rains, the Gentleman Farmer By Raquel Stecher

In 1967, actor Claude Rains was laid to rest next to his wife Rosemary in Red Hill Cemetery, situated in the tiny New Hampshire town of Moultonborough. His gravesite is just a few miles away from his farmhouse in nearby Sandwich. Built in 1850, The Weed House is a gorgeous Greek Revival style home with an adjacent barn. It was here that Rains spent the last few years of his life taking care of Rosemary, who died of cancer in 1964, tending the land and enjoying the solitude of rustic life. How did the British-born actor—who became the toast of the film industry and would go on to earn four Academy Award nominations for his roles in MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON (‘39), CASABLANCA (‘42), MR. SKEFFINGTON (‘44) and NOTORIOUS (‘46)—wind up in such a small town so far away from the bright lights of Hollywood?

Rains had a tumultuous childhood and at an early age got a job as a call boy for a local theatre. The majority of his earnings went back to his impoverished family, and what little was left for himself went to food and transportation. He would often go to bed hungry and sometimes would walk the distances to and from work just to be able to afford a little extra food. The volatility of theatre work and the lack of resources in his home life must have made Claude Rains long for stability. After working up the ladder in the theatre world, Rains became a successful stage actor. He moved to the U.S. in the 1920s with his third wife, actress Beatriz Thomas.

Once settled, he bought a farm in Lambertville, NJ. When that home burned down, he moved around and eventually settled in Pennsylvania. According to Rains biographer David J. Skal, with the onset of the Great Depression, Rains felt that having a homestead, somewhere he could grow his own food, was a good back-up in case his acting career ever fell through. When Hollywood came calling, Rains made the practical decision of transitioning to the more lucrative film business. However, he was never really interested in making Los Angeles his home. After marrying his fourth wife Frances Propper, he split his time between Hollywood and Pennsylvania. Rains was quoted as saying “Hollywood to me is a place to work. Home is Chester County.”

Rains crisscrossed the country, working in Hollywood and retreating to a much quieter life in rural Pennsylvania. He bought Stock Grange Farm, a colonial farmhouse built in 1747 which sat on almost 400 acres of land in West Bradford Township. There he, his wife and daughter Jennifer (who later went by the name Jessica Rains professionally), raised cattle, chickens and pigs, churned butter and harvested grains and vegetables. Rains was a great student of agriculture, kept scrapbooks on farm life and would even bring books on farming with him on movie sets to study in between takes. He much preferred the quiet life of the farmer, and while he relished his work as an actor, he was not interested in being a Hollywood celebrity. When Rains’ workload increased in the 1940s, he bought a modest home in Beverly Hills. According to Skal, when Warner Bros. terminated his contract, “Rains was happy to be a free agent and more than happy to give up his residence in Los Angeles and base himself, Frances and Jennifer permanently in Pennsylvania. Thereafter, when asked by her schoolmates what her father did for a living, Jennifer would reply, ‘He’s a farmer.’”

When Rains and Frances divorced in 1957, Rains sold his beloved Stock Grange and moved into the smaller Hawthorne House in West Chester. With Rains’ acting career winding down in the early 1960s, he moved with his sixth wife, Rosemary, up to New Hampshire. In the 1940s and 1950s, Rains had taken family trips up to New Hampshire where Jennifer had spent summers at camp. Rains had fond memories of those trips and asked a realtor to find him a home similar to Hawthorne House in the Lake Winnipesaukee region. He purchased the beautiful Weed House where he and Rosemary settled in. It was perfect for Rains, who was drawn to quiet, secluded places. When Rosemary became ill, Rains bought a lake-side cottage so Rosemary would have a nice view of the water, but according to Skal, they had to return to the farmhouse a couple of months later due to inclement weather. Rains took great care of Weed House. According to the Sandwich Historical Society, “Claude Rains believed one should honor the integrity of historic houses and barns; he restored but never remodeled any home in which he lived.”

Rains enjoyed the privacy Sandwich had to offer and for the most part kept a low profile. When tourists came to town asking where Rains lived, locals, who had the utmost respect for Rains, would claim they didn’t know. After Rosemary died in 1964, Rains returned to acting briefly only to retreat to the Weed House due to illness. He died in 1967 at the Lakes Region Hospital in Laconia, NH. His tombstone reads “All things once, Are things forever, Soul, once living, lives forever.” Rains never had to sacrifice his love for agriculture and rural life for his love of acting and ultimately proved he could live his life on his own terms.

#Claude Rains#farming#homesteading#Holllywood farmers#Casablanca#green thumb#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Year’s Eve in Classic Movies By Raquel Stecher

There are few things that fill me with more joy than a terrific New Year’s Eve celebration in a classic movie. New Year’s is a special holiday and, in my opinion, highly underrated. Think about it. It’s essentially everyone’s birthday. It’s a time for us to turn the page into a new chapter in our lives individually and collectively. It’s a time of hope, of resolution, of embracing change and of setting new goals for the future.

In movies, New Year’s can effectively demonstrate a character’s evolution. It can be strategic in a plot where the character sheds an old life in order to transition to a new one. It’s also a fantastic way to depict revelry with a grand party filled with confetti, streamers, noisemakers and a glass of champagne or two. And if you’re the type who prefers to stay at home for New Year’s, binge watching classic films like THE THIN MAN series or the Marx Bros. movies can be a wonderful way to wind down. Let’s ring in the New Year with some classic movies that embrace this very special holiday together.

When I think of New Year’s movies the first one that comes to mind is BACHELOR MOTHER (’39). Starring Ginger Rogers and David Niven, this delightful romantic comedy tells the story of a shopgirl who inadvertently winds up with an orphan baby and cannot convince anyone in her life that the baby is not her own. BACHELOR MOTHER has my favorite New Year’s Eve sequence. Rogers gets a complete makeover with new pieces from the department store, including a shimmery dress, a mink coat adorned with orchids, a veil, a purse, gloves and shoes. She is the epitome of elegance. The class difference becomes apparent here as David (David Niven) convinces Polly (Ginger Rogers) to speak fake Swedish so she won’t feel out of place with David’s upper-class cohorts. This is done to great comedic effect. The sequence goes on to include a four-course meal and plenty of dancing. The lovebirds get separated in a crowd in Times Square only to be reunited just in time for a New Year’s kiss.

In the Rat Pack movie OCEAN’S 11 (’60), New Year’s serves as the perfect time to orchestrate a major heist. Led by Danny Ocean (Frank Sinatra), his team of 11 WWII buddies plan to rob millions from five Las Vegas casinos: the Desert Inn, the Flamingo, the Riviera, the Sahara and the Sands. The film stars Rat Packers Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford, Dean Martin and Joey Bishop accompanied by other talent including Richard Conte and Akim Tamiroff. The heist is timed specifically to ringing in of 1960. As everyone sings “Auld Lang Syne,” two members of the team blow up an electrical tower, blacking out the entire Las Vegas Strip. This is when the rest of the team get to work robbing each of the five casinos and making their escape. The characters find themselves at a crossroads in their lives in one way or another. While this isn’t explored with every character, it is examined with a handful. There has to be an impetus for them to commit this crime. New Year’s in 1960’s Las Vegas is a mix of kitsch and glamour. Each of the casinos has their own outlandishly styled party.

Who wouldn’t want to ring in the New Year with Nick and Nora (William Powell and Myrna Loy)? In AFTER THE THIN MAN (’36), the duo visits the Lychee Club, a seedy nightclub, on a mission to help Nora’s cousin Selma (Elissa Landi). Her husband Robert (Alan Marshall) has been missing for three days and the two discover that Robert has gotten involved with the wrong crowd. The film boasts a wild welcome home party followed by an equally epic New Year’s party at the Lychee. Nora tells Nick that she’s looking forward to their “first New Year’s alone” when suddenly they are joined by a group of ex-cons. Nick enjoys the revelry with scotch in one hand and a toy saxophone in another. There is an accidental kiss, lots of streamers, plenty of booze and two song-and-dance numbers led by hoofer/actress Penny Singleton.

THE APARTMENT (’60) is best known for being a dark romantic comedy set during the Christmas season, but New Year’s proves to be a major turning point for the two main characters. C.C. Baxter (Jack Lemmon) is working his way up the corporate ladder by letting his superiors make use of his apartment for their extramarital trysts. Things get complicated when he discovers that his love interest, elevator operator Miss Kubelik (Shirley MacLaine), is having an affair with his boss. Their Christmas Eve is dire with Kubelik attempting suicide and Baxter trying to bring her back to some semblance of a life. The New Year’s Eve sequence, set in a Chinese nightclub, much like in AFTER THE THIN MAN, is when Kubelik realizes she wants to shed he old life and start afresh. She quietly says “ring out the old year, ring in the new. Ring-a-ding-ding” as she contemplates a new life for herself, resulting in one of the most iconic ending scenes and lines in movie history.

#New Years Eve#New Year's#2021#2020#celebration#party#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Ginger Rogers#Rat Pack#The Apartment#Thin Man#Nick and Nora Charles#1930s#1940s#1960s#Raquel Stecher

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Noir Christmas Double Feature By Raquel Stecher

Christmas is a time of heightened emotion and sentimentality. There is deep nostalgia for ritual and tradition and a prevalent feeling of generosity and goodwill towards other. But what if you threw a murder into the mix? That’s just what a good Christmas film noir will do while still offering a hearty dose of Christmas cheer. As Christmas movies evolved over time, audiences got to see all sorts of holiday fare, including romantic comedies, musicals, dramas and even thrillers. And in the 1940s, when film noir was coming into its own as an aesthetic and a genre of sorts, it was inevitable that Christmas would be included as a backdrop or, in some cases, an important plot element. Let’s take a look at two Christmas noir films that put the holiday front and center while also delivering intriguing murder mysteries.

LADY ON A TRAIN (’45) was an opportunity for Universal Studios to rebrand their biggest star, Deanna Durbin. The talented singer was such a huge star she helped her home studio avoid bankruptcy during the turbulent years of the Great Depression. However, Durbin was growing up and growing out of her juvenile roles and wanted something new and fresh. Producer Felix Jackson was in charge of finding new film projects for her and commissioned British-Chinese mystery writer Leslie Charteris, who was best known for The Saint novels and subsequent movie series and television show, to write an original screenplay with Durbin in mind. He concocted the story LADY ON A TRAIN, which follows sophisticated San Francisco debutante Nikki Collins, who, on a train trip to New York City to visit her aunt for Christmas, witnesses a murder from her window.

The mystery novel-obsessed Nikki investigates the crime on her own, often getting herself into prickly situations. Durbin is supported by a cast of fantastic character actors, including Edward Everett Horton, Allen Jenkins, Ralph Bellamy and Dan Duryea. Durbin plays the equivalent of a glamorous and adult Nancy Drew. The events in the story lead up to Christmas Day, which puts pressure on the lead as her time in the city is limited, and Durbin sings a beautiful rendition of “Silent Night.” The concept behind LADY ON A TRAIN has been revisited in novels, television episodes and films ever since, like in the modern-day thriller THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN (2016). Durbin starred in another Christmas noir the previous year, CHRISTMAS HOLIDAY (‘44), which also starred Gene Kelly.

In the independently produced film noir COVER UP (’49), Dennis O’Keefe plays Sam Donovan, an insurance detective who travels to a small town during the Christmas season to investigate a supposed suicide. While carrying Christmas gifts for his train companion, he meets Anita (Barbara Britton), a young woman who lives in the community and has ties to several key figures in the case. The movie deals with the theme of small-town life and the importance of community. The residents of the town protect their own, and it’s clear that while the suicide is really a murder, Sam, an outsider, will have to overcome obstacles they place in front of him to get to the truth. A pivotal moment in the film takes place during the annual ritual of lighting the Christmas tree in the town square. It’s at that moment when Sam realizes what he’s gotten himself into.

There are some tender holiday scenes including one in which the insurance detective places a small present underneath the even smaller Christmas tree at the sheriff’s office and proclaims, “Home is wherever I happen to hang my hat.” It’s clear that O’Keefe’s character, a nomadic career man with no family of his own, will find what he’s missing in his life in this quaint little town. COVER UP is filled with charming characters, like William Bendix as the cynical sheriff, Ann E. Todd as the lovestruck teenager and Doro Merande, as the devoted housekeeper who will do anything to protect the family she works for, even destroy potentially incriminating evidence. COVER UP almost lost its Christmas setting when it was suggested that the screenplay be altered. Dennis O’Keefe who not only starred in the film but also co-wrote the screenplay under the pseudonym Jonathan Rix, fought to keep the Christmas elements. Ultimately, this was a wise decision as COVER UP benefits from the holiday backdrop. It watches almost like a light Christmas noir version of DOUBLE INDEMNITY (‘44).

#Christmas noir#christmas crime#noir#film noir#murder mystery#Deanna Durbin#Cover Up#Lady on a Train#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Garfield: Actor, Boxer and the Film That Got Away By Raquel Stecher

From an early age, John Garfield found an outlet for his athleticism and creativity in both boxing and acting. These two things would be intrinsically linked throughout Garfield’s career as a Hollywood actor. Garfield was the son of Jewish immigrants living in the Lower East Side of New York City. His mother died when he was 7 years old. He soon spent many of his formative years in rough neighborhoods, where he began to spar with local kids, joined street gangs and even became a gang leader. His father put in him in the Bronx’s PS 45, known as a school for problem children.

At PS 45, principal Angelo Patri encouraged Garfield to take up boxing as a means to channel his aggression and also drama so he could work on his confidence. Garfield excelled at both. He worked his way up the amateur boxing ranks and even became a semi-finalist in a Golden Gloves tournament. But his true calling was acting. He soon became part of the theatre collective called The Group where he developed his talents. Hollywood soon came calling and it was a short while before he became a leading man at one of the biggest movie studios. However, his film career was prefaced by a life-altering disappointment.

Garfield’s good friend, playwright Clifford Odets, was so impressed with Garfield’s acting chops that he was inspired to write a play with him in mind. The play was Golden Boy, a melodrama about a struggling young violinist who becomes a boxer to make ends meet. Garfield played the lead role of Joe Bonaparte in a Group Theatre production. Odets story hit Broadway with Luther Adler as the lead and then Columbia Pictures secured the movie rights. Many actors were considered for the part but director Rouben Mamoulian had two in mind: Richard Carlson and William Holden. Carlson was otherwise unavailable, and the part went to William Holden. Under the tutelage of his co-star Barbara Stanwyck, this would prove to be Holden’s breakout role. For Garfield, missing out on GOLDEN BOY (’39) left a bad taste in his mouth. It was a defeat, but it wasn’t the end of the battle.

Garfield soon signed with Warner Bros. studios and made the trek from New York City to Hollywood to begin the next phase in his acting career. His first film, FOUR DAUGHTERS (’38), was a crowd pleaser and a critical success. It earned Garfield an Academy Award nomination and his studio quickly revised his contract to make him a leading man. The powers that be got to work on Garfield’s second picture, a film custom-made to build him up as a leading man. THEY MADE ME A CRIMINAL (’39) combined two elements that worked well at the time: gangsters and boxing. Garfield starred as a boxer who had been too drunk to remember whether he had committed a major crime. While on the lam, he adopts a new identity and stumbles upon a home for wayward boys where he must come to terms with his past and his future.

Starring alongside Garfield were the Dead End Kids as well as Claude Rains, who was hopelessly miscast as a New York City detective. The film was directed by Busby Berkeley who was better known for his meticulously choreographed musical numbers in major pre-Code productions. For THEY MADE ME A CRIMINAL, Berkeley opted for realism over choreography and allowed Garfield and other trained boxers to navigate their way inside the ring. As a result, the boxing scenes in the film are authentic and set the bar for future boxing films to come. And while the movie itself was not a success, it proved that Garfield could carry a picture as a leading man.

After seven years at Warner Bros., a few loan outs, including the opportunity to star in the film noir classic THE POSTMAN ALWAYS RINGS TWICE (’46), Garfield decided that he wouldn’t renew his studio contract. He became one of the first Hollywood actors to go freelance, opting to work individually with studios like Fox and MGM or with independent production companies. Producer Bob Roberts and Garfield joined forces to found Roberts Pictures Inc. which worked closely with Enterprise Studios to develop and distribution feature films. Their first project together was another boxing movie: BODY AND SOUL (’47). This would prove to be one of Garfield’s finest and most gratifying performances.

Originally, Roberts and Garfield had intended for the film to be a biopic of Barney Ross, a champion prize fighter who fought his way out of a heroin addiction. Unfortunately, the censors would not allow for a story about drug addiction, so instead they enlisted Abraham Polonsky to write an original screenplay. Polonsky crafted a quality script, partly based on Garfield’s own story as a Jewish immigrant growing up in New York City and partly based on Odets’ Golden Boy. The script told the story of a boxer who is driven to succeed in order to support his family but soon becomes the pawn of a corrupt promoter. Polonsky’s anti-capitalist message spoke to the devastating effects of greed. BODY AND SOUL also upped the ante with even more authentic scenes in the boxing ring.

Alongside Garfield was renowned black actor Canada Lee, who was a former welterweight boxer himself. He plays Garfield’s opponent, friend and a tragic victim of the boxing world’s corruption. Cinematographer James Wong Howe, crouched on roller skates, was maneuvered within the ring to capture the action as it happened. The finished film was praised by many. Both Garfield’s performance and Polonsky’s script earned Academy Award nominations. With BODY AND SOUL, Garfield got the boxing story he missed out on with GOLDEN BOY. In the wise words of New York Post writer Archer Winsten: “It’s a striking commentary on Hollywood and its waste of talents that Garfield, an actor who was perfectly capable of doing this job nine years ago when he first left the New York stage, should have had to wait so long and impersonate so many variously repetitious types before he could realize his full capabilities.”

52 notes

·

View notes