#did you know that these buildings were inspired by le corbusier

Text

#architecture#architektur#plattenbau#neubaugebiet#large panel system building#wikipedia tells me#concrete#prefabricated#building blocks#block#house#housing#building#beton#haus#wohnhaus#tower block#the good shit#did you know that these buildings were inspired by le corbusier#now you know#denmark#danmark#photography#fotografie#lensblr#photographers on tumblr

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Brutalism Post Part 3: What is Brutalism? Act 1, Scene 1: The Young Smithsons

What is Brutalism? To put it concisely, Brutalism was a substyle of modernist architecture that originated in Europe during the 1950s and declined by the 1970s, known for its extensive use of reinforced concrete. Because this, of course, is an unsatisfying answer, I am going to instead tell you a story about two young people, sandwiched between two soon-to-be warring generations in architecture, who were simultaneously deeply precocious and unlucky.

It seems that in 20th century architecture there was always a power couple. American mid-century modernism had Charles and Ray Eames. Postmodernism had Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. Brutalism had Alison and Peter Smithson, henceforth referred to simply as the Smithsons.

If you read any of the accounts of the Smithsons’ contemporaries (such as The New Brutalism by critic-historian Reyner Banham) one characteristic of the pair is constantly reiterated: at the time of their rise to fame in British and international architecture circles, the Smithsons were young. In fact, in the early 1950s, both had only recently completed architecture school at Durham University. Alison, who was five years younger, was graduating around the same time as Peter, whose studies were interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served as an engineer in India.

Alison and Peter Smithson. Image via Open.edu

At the time of the Smithsons graduation, they were leaving architecture school at a time when the upheaval the war caused in British society could still be deeply felt. Air raids had destroyed hundreds of thousands of units of housing, cultural sites and had traumatized a generation of Britons. Faced with an end to wartime international trade pacts, Britain’s financial situation was dire, and austerity prevailed in the 1940s despite the expansion of the social safety net. It was an uncertain time to be coming up in the arts, pinned at the same time between a war-torn Europe and the prosperous horizon of the 1950s.

Alison and Peter married in 1949, shortly after graduation, and, like many newly trained architects of the time, went to work for the British government, in the Smithsons’ case, the London City Council. The LCC was, in the wake of the social democratic reforms (such as the National Health Service) and Keynesian economic policies of a strong Labour government, enjoying an expanded range in power. Of particular interest to the Smithsons were the areas of city planning and council housing, two subjects that would become central to their careers.

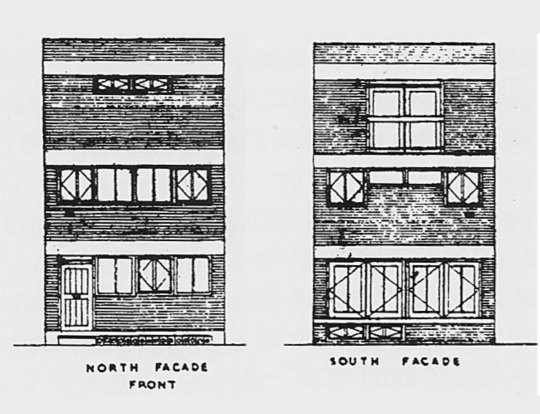

Alison and Peter Smithson, elevations for their Soho House (described as “a house for a society that had nothing”, 1953). Image via socks-studio.

The State of British Architecture

The Smithsons, architecturally, ideologically, and aesthetically, were at the mercy of a rift in modernist architecture, the development of which was significantly disrupted by the war. The war had displaced many of its great masters, including luminaries such as the founders of the Bauhaus: Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. Britain, which was one of the slowest to adopt modernism, did not benefit as much from this diaspora as the US.

At the time of the Smithsons entry into the architectural bureaucracy, the country owed more of its architectural underpinnings to the British architects of the nineteenth century (notably the utopian socialist William Morris), precedent studies of the influences of classical architecture (especially Palladio) under the auspices of historians like Nikolaus Pevsner, as well as a preoccupation with both British and Scandinavian vernacular architecture, in a populist bent underpinned by a turn towards social democracy. This style of architecture was known as the New Humanism.

Alton East Houses by the London County Council Department of Architecture (1953-6), an example of New Humanist architecture. Image taken from The New Brutalism by Reyner Banham.

This was somewhat of a sticky situation, for the young Smithsons who, through their more recent schooling, were, unlike their elders, awed by the buildings and writing of the European modernists. The dramatic ideas for the transformation of cities as laid out by the manifestos of the CIAM (International Congresses for Modern Architecture) organized by Le Corbusier (whose book Towards a New Architecture was hugely influential at the time) and the historian-theorist Sigfried Giedion, offered visions of social transformation that allured many British architects, but especially the impassioned and idealistic Smithsons.

Of particular contribution to the legacy of the development of Brutalism was Le Corbusier, who, by the 1950s was entering the late period of his career which characterized by his use of raw concrete (in his words, béton brut), and sculptural architectural forms. The building du jour for young architects (such as Peter and Alison) was the Unité d’Habitation (1948-54), the sprawling massive housing project in Marseilles, France, that united Le Corbusier’s urban theories of dense, centralized living, his architectural dogma as laid out in Towards a New Architecture, and the embrace of the rawness and coarseness of concrete as a material, accentuated by the impression of the wooden board used to shape it into Corb’s looming, sweeping forms.

The Unité d’habitation by Le Corbusier. Image via Iantomferry (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Little did the Smithsons know that they, mere post-graduates, would have an immensely disruptive impact on the institutions they at this time so deeply admired. For now, the couple was on the eve of their first big break, their ticket out of the nation’s bureaucracy and into the limelight.

The Hunstanton School

An important post-war program, the one that gave the Smithsons their international debut, was the expansion of the British school system in 1944, particularly the establishment of the tripartite school system, which split students older than 11 into grammar schools (high schools) and secondary modern schools (technical schools). This, inevitably, stimulated a swath of school building throughout the country. There were several national competitions for architects wanting to design the new schools, and the Smithsons, eager to get their hands on a first project, gleefully applied.

For their inspiration, the Smithsons turned to Mies van der Rohe, who had recently emigrated to the United States and release to the architectural press, details of his now-famous Crown Hall of the Illinois Institute of Technology (1950). Mies’ use of steel, once relegated to being hidden as an internal structural material, could, thanks to laxness in the fire code in the state of Illinois, be exposed, transforming into an articulated, external structural material.

Crown Hall, Illinois Institute of Technology by Mies van der Rohe. Image via Arturo Duarte Jr. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Of particular importance was the famous “Mies Corner,” consisting of two joined exposed I-beams that elegantly elided inherent problems in how to join together the raw, skeletal framing of steel and the revealing translucence of curtain-wall glass. This building, seen only through photographs by our young architects, opened up within them the possibility of both the modernist expression of a structure’s inherent function, but also as testimony to the aesthetic power of raw building materials as surfaces as well as structure.

The Smithsons, in a rather bold move for such young architects, decided to enter into a particularly contested competition for a new secondary school in Norfolk. They designed a school based on a Miesian steel-framed design of which the structural elements would all be visible. Its plan was crafted to the utmost standards of rationalist economy; its form, unlike the horizontal endlessness of Mies’ IIT, is neatly packaged into separate volumes arranged in a symmetrical way. But what was most important was the use of materials, the rawness of which is captured in the words of Reyner Banham:

“Wherever one stands within the school one sees its actual structural materials exposed, without plaster and frequently without paint. The electrical conduits, pipe-runs, and other services are exposed with equal frankness. This, indeed, is an attempt to make architecture out of the relationships of brute materials, but it is done with the very greatest self-denying restraint.”

Much to the upset and shock of the more conservative and romanticist British architectural establishment, the Smithsons’ design won.

Hunstanton School by Alison and Peter Smithson (1949-54). Photos by Anna Armstrong. (CC BY NC-SA 3.0)

The Hunstanton School, had, as much was possible in those days, gone viral in the architectural press, and very quickly catapulted the Smithsons to international fame as the precocious children of post-war Britain. Soon after, the term the Smithsons would claim as their own, Brutalism, too entered the general architectural consciousness. (By the early 1950s, the term was already escaping from its national borders and being applied to similar projects and work that emphasized raw materials and structural expression.)

The New Brutalism

So what was this New Brutalism?

The Smithsons had, even before the construction of the Hunstanton School had been finished, begun to draft amongst themselves a concept called the New Brutalism. Like many terms in art, “Brutalism” began as a joke that soon became very serious. The term New Brutalism, according to Banham, came from an in-joke amongst the Swedish architects Hans Asplund, Bengt Edman and Lennart Holm in 1950s, about drawings the latter two had drawn for a house. This had spread to England through the Swedes’ English friends, the architects Oliver Cox and Graeme Shankland, who leaked it to the Architectural Association and the Architect’s Department of the London County Council, at which Alison and Peter Smithson were still employed. According to Banham, the term had already acquired a colloquial meaning:

“Whatever Asplund meant by it, the Cox-Shankland connection seem to have used it almost exclusively to mean Modern Architecture of the more pure forms then current, especially the work of Mies van der Rohe. The most obstinate protagonists of that type of architecture at the time in London were Alison and Peter Smithson, designers of the Miesian school at Hunstanton, which is generally taken to be the first Brutalist building.”

(This is supplicated by an anecdote of how the term stuck partially because Peter was called Brutus by his peers because he bore resemblance to Roman busts of the hero, and Brutalism was a joining of “Brutus plus Alison,” which is deeply cute.)

The Smithsons began to explore the art world for corollaries to their raw, material-driven architecture. They found kindred souls in the photographer Nigel Henderson and the sculptor Edouardo Paolozzi, with whom the couple curated an exhibition called “Parallel of Life and Art.” The Smithsons were beginning to find in their work a sort of populism, regarding the untamed, almost anthropological rough textures and assemblies of materials, which the historian Kenneth Frampton jokingly called ‘the peoples’ detailing.’ Frampton described the exhibit, of which few photographs remain, as thus:

“Drawn from news photos and arcane archaeological, anthropological, and zoological sources, many of these images [quoting Banham] ‘offered scenes of violence and distorted or anti-aesthetic views of the human figure, and all had a coarse grainy texture which was clearly regarded by the collaborators as one of their main virtues’. There was something decidedly existential about an exhibition that insisted on viewing the world as a landscape laid waste by war, decay, and disease – beneath whose ashen layers one could still find traces of life, albeing microscopic, pulsating within the ruins…the distant past and the immediate future fused into one. Thus the pavilion patio was furnished not only with an old wheel and a toy aeroplane but also with a television set. In brief, within a decayed and ravaged (i.e. bombed out) urban fabric, the ‘affluence’ of a mobile consumerism was already being envisaged, and moreover welcomed, as the life substance of a new industrial vernacular.”

Alison and Peter Smithson, Nigel Henderson, Eduoardo Paolozzi, Parallels in Life and Art. Image via the Tate Modern, 2011.

A Clash on the Horizon

The Smithsons, it is important to remember, were part of a generation both haunted by war and tantalized by the car and consumer culture of the emerging 1950s. Ideologically they were sandwiched between the twilight years of British socialism and the allure of a consumerist populism informed by fast cars and good living, and this made their work and their ideology rife with contradiction and tension.

The tension between proletarian, primitivist, anthropological elements as expressed in coarse, raw, materials and the allure of the technological utopia dreamed up by modernists a generation earlier, combined with the changing political climate of post-war Britain, resulted in a mix of idealism and post-socialist thought. This hybridized an new school appeal to a better life - made possible by technology, the emerging financial accessibility of consumer culture, the promises of easily replicable, luxurious living promised by modernist architecture - with the old-school, quintessentially British populist consideration for the anthropological complexity of urban, working class life. This is what the Smithsons alluded to when they insisted early on that Brutalism was an “ethic, not an aesthetic.”

Model of the Plan Voisin for Paris by Le Corbusier displayed at the Nouveau Esprit Pavilion (1925) via Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0)

By the time the Smithsons entered the international architectural scene, their modernist forefathers were already beginning to age, becoming more stylistically flexible, nuanced, and less reliant upon the strictness and ideology of their previous dogmas. The younger generation, including the Smithsons, were, in their rose-tinted idealism, beginning to feel like the old masters were abandoning their original ethos, or, in the case of other youngsters such as the Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck, were beginning to question the validity of such concepts as the Plan Voisin, Le Corbusier’s urbanist doctrine of dense housing development surrounded by green space and accessible by the alluring future of car culture.

These youngsters were beginning to get to know each other, meeting amongst themselves at the CIAM – the International Congresses of Modern Architecture – the most important gathering of modernist architects in the world. Modern architecture as a movement was on a generational crash course that would cause an immense rift in architectural thought, practice, and history. But this is a tale for our next installment.

Like many works and ideas of young people, the nascent New Brutalism was ill-formed; still feeling for its niche beyond a mere aesthetic dominated by the honesty of building materials and a populism trying to reconcile consumerist technology and proletarian anthropology. This is where we leave our young Smithsons: riding the wave of success of their first project as a new firm, completely unaware of what is to come: the rift their New Brutalism would tear through the architectural discourse both then and now.

If you like this post, and want to see more like it, consider supporting me on Patreon!

There is a whole new slate of Patreon rewards, including: good house of the month, an exclusive Discord server, monthly livestreams, a reading group, free merch at certain tiers and more!

Not into recurring donations or bonus content? Consider the tip jar! Or, Check out the McMansion Hell Store! Proceeds from the store help protect great buildings from the wrecking ball.

#brutalism#architecture#architectural history#brutalism post#smithsons#alison and peter smithson#british architecture#modern architecture#le corbusier#concrete#brutalist architecture

933 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twenty-two women architects and designers you should know

To mark International Women's Day, we asked 22 of the world's most inspirational women architects and designers to nominate another woman who should be better known for their work.

Each of the prominent architects and designers was asked to select a woman who they think deserves greater recognition.

Several chose to shine a light on historic figures who did not receive full recognition in their lifetimes, with MVRDV co-founder Nathalie de Vries, Bangladeshi architect Marina Tabassum and Neri&Hu co-founder Rossana Hu nominating Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, Minnette de Silva and Lin Huiyin respectively.

Others took the opportunity to draw attention to a contemporary woman or women-led team that should be better known, with Camille Walala, Tatiana Bilbao, Dorte Mandrup and Eva Franch i Gilabert nominating Unscene Architecture, Taller Comunal, Marie-José Van Hee and V. Mitch McEwen respectively.

Read on for the 22 architects and designers that deserve greater recognition:

Marie-José Van He

Nominated by Dorte Mandrup, Dorte Mandrup Arkitekter

"Marie-José Van Hee is a remarkably talented architect. Working primarily in her native country, Belgium, she is forging a significant mark on contemporary architecture with her attention to space, light and natural materials.

"Through her understated, authentic and poetic work, she continuously influences and inspires architects and designers alike. A timeless simplicity and weightlessness permeate throughout her designs, creating a stillness that seems almost tangible – blurring the line between art and architecture."

Iwona Buczkowska

Nominated by Farshid Moussavi, Farshid Moussavi Architecture

"Polish-born French architect Iwona Buczkowska's brilliant career is distinguished by an architectural approach opposed to any form of standardisation, thus placing the diversity of users and their agency at the core of her work. Her tireless commitment has led to the creation of works of incredible richness and inventiveness, whether for housing projects or public facilities.

"At a time when we need to question our built environment, and in particular, the housing in which we live, her work on diversification, user empowerment and inclusion seems particularly worthy of attention. As her work is under-studied, and because some of her built projects are currently under threat of demolition, I feel it is particularly important to bring to light what her work has to teach us."

Charlotte Perriand

Nominated by Es Devlin, Es Devlin Studio

"Last weekend I went to the South Downs to try to recreate this uplifting portrait of Charlotte Perriand (above) about which her daughter said: 'That photograph of a strong woman, triumphantly embracing nature, is the perfect image of my mother. She announces the contemporary woman, emancipated and free.

"Most of us have sat on the extraordinary and now iconic furniture she made in collaboration with Le Corbusier. Most of us are unaware of her fundamental role in its design. She was a genius in the art of collaboration, especially with powerful male artists. Her practice spanned an astounding range of genres, her work drew deeply on the forms she observed in nature throughout her rich life."

Kenyatta Mclean

Nominated by Harriet Harriss, dean of the Pratt Institute School of Architecture

"I'd like to nominate Kenyatta Mclean, co-founder and co-managing director of Blackspace: the black, interdisciplinary, spatial collective comprised of architects, artists, designers and planners who have asserted both the necessity and the agency of 'Black Urbanism'.

"From my perspective, her ability to co-create spatial narratives that are centred in and driven by racial justice is essential and urgent work applicable both to the US where the practice is situated, and cities worldwide, where structural racism and other forms of discrimination are embedded in the materiality and form of the architectures that surround us.

"Moreover, spatial collectives – from Matrix to Assemble – offer a much-needed antidote to the vagaries of starchitecture and the hierarchies typically found in traditional design practices. Kenyatta Mclean's visionary work reminds us all of the need to use this period of Covid-imposed introspection to re-examine how much more inclusive, equitable and impactful our industry needs to become.

"Blackspace also offers a road map and a benchmark for graduates and young practitioners who are committed to leading the changes we need to make."

Unscene Architecture

Nominated by Camille Walala, Studio Walala

"I would like to nominate Unscene Architecture. A pair of fantastic women that I met the year before the pandemic started. The architecture design duo – founders Manijeh Verghese and Madeleine Kessler – were the co-creators of the British Pavilion for the postponed 2020 Venice Architecture Biennale. Definitely, ones to watch."

Anupama Kundhoo

Nominated by Seetal Solanki

"A rare kind within the world of architecture. Anupama Kundhoo brings people a voice, materials a voice and building a voice that is beyond her own – an egoless practice. Traits that shouldn't be so rare actually, but she's paving the way for so many and hopefully many more to come."

Ndebele women

Nominated by Sumayya Vally, Counterspace

"In this tribe, we evoke women near and far – friends, ancestors and mythical figures – women who write, organise, imagine and build worlds into being. I chose to draw attention to the unrecognised architect genius of the Ndebele women – women who craft ritual objects and build and adorn their own homes. The calling of their names invokes the calling of millions of errant, unrecognised, other architects the world over – past, present and future.

"They are Maria Ntobela Mahlangu, Dinah Mahlangu, Johanna Mkwebani, Martina Maghlangu, Anna Msiza, Sara Mthimunye, Sara and Lisbeth, Pikinini and Sara Skosana, Anna Mahlangu, Letty Ngoma, Sarah Mguni, Martha Mtsweni Ndala, Rossinah and Esther Mahlangu."

Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak

Nominated by Nathalie de Vries, MVRDV

"When working on our Concordia Design project in Wroclaw, Poland, I met Jadwiga Grabowska-Hawrylak, the grande dame of modern Polish architecture. Born in 1920, she brought architecture to the next level in the second half of the 20th century. In 1974, she was the first woman to receive the prestigious Honorary Award from the Association of Polish Architects.

"In a time when female Polish architects were mostly known as 'the wife of…' Jadwiga had a highly successful career, she had a big part in rebuilding postwar Wroclaw, and was also known for her schools and housing. I am really impressed by her work and her amazing personality. When I met her, she was very energetic and still very much involved in architecture. With her passing in 2018, Poland lost a great architect."

Minnette de Silva

Nominated by Marina Tabassum

"The first name that comes to mind is Minnette de Silva (pictured above with Pablo Picasso), an architect ahead of her time. Less celebrated than her contemporary male counterparts. You may have read this article below, but I'm sharing the link again. This tells her story better than I can write."

Marina Willer

Nominated by Margaret Calvert

"I would propose Marina Willer, although she may not fit as she's already well known. Apart from being an exceptional graphic designer and filmmaker, Marina was the first woman to be appointed a Pentagram partner. Brazilian by birth, it was at the Royal College of Art, where I was teaching at the time, that I first became aware of her amazing drive, commitment and talent as a student."

Duygu and Begum Ozturk

Nominated by Nelly Ben Hayoun, Nelly Ben Hayoun Studios

"I nominate Duygu and Begum Ozturk, the two sisters behind the fashion brand Harem London. Born in Istanbul, they started their all-organic fashion brand recently in Dalston, London; merging traditional techniques from Istanbul and London, bringing together their heritage and future.

"I love that they started a business together as sisters and that they are persevering in developing their beautiful collection despite the pandemic and Brexit and all the complexity this created for them. They need to be applauded for their great work."

Lin Huiyin

Nominated by Rossana Hu, Neri&Hu

"Lin Huiyin was the first female architect in modern China. Lin and her partner Liang Sicheng were the pioneers in architectural heritage restoration and documentation in China during the 1930s.

"Although it was the two of them who brought China's ancient architectural treasures to light, Lin's recognition in documenting and restoring China's historic buildings has often been overshadowed by her partner, who is recognised as the 'father of modern Chinese architecture'. In addition to her architectural practice, Lin is also widely acclaimed for her literary creation."

Mary Corse

Nominated by Azusa Murakami, Studio Swine

"I would like to pick Mary Corse. She has been gaining much-deserved recognition in recent years with a solo show at the Whitney but has been arguably one of the most innovative artists to come out of the light and space movement.

"We love her material research, her ability to take industrial elements like the glass microbeads used on motorway reflective road markings and using it to make really delicate and sublime optical paintings is really inspiring."

Yemi Awosile

Nominated by Morag Myerscough

"I have loved Yemi Awosile's work for many years. She is a wonderful person and I have worked with her in the past on the Bernie Grant Centre where she made some textiles for the centre."

Franziska Porges Hosken

Nominated by Jane Hall, Assemble

"Austrian-born, and America-based, designer Franziska Porges Hosken was pioneering in multiple respects. In 1944 she became one of the first women to receive her master's of architecture degree from Harvard's Graduate School of Design and in 1947, together with her husband James Hosken, she founded their successful eponymous furniture business Hosken.

"Despite giving up her design practice to take care of her first child in the late 1950s, Hosken continued to create as a photographer and journalist, publishing numerous books on urbanism including The Language of Cities.

"She was also an activist for women's rights, founding the Women's International Network and publishing reports on Female Genital Mutilation (FGM), a term she is credited with coining, which affected the agenda of major health organisations including the WHO. Continuing to distribute a feminist newsletter well into her eighties, Hosken's legacy demonstrates an extraordinary commitment, undertaken over the course of a lifetime, to connect design with social activism."

Winka Dubbeldam

Nominated by Sonali Rastogi, Morphogenesis

"Winka Dubbeldam is an architect whose contribution I would like to acknowledge. She is the founder of the WBE firm Archi-Tectonics. She had visited our studio about 15 years back whilst working on the redevelopment of the New Delhi railway station. I also enjoyed attending one of her juries in UPenn about ten years ago, and ever since, I have been following her.

"Being in academia myself, what resonates with me is her significant influence on the emerging generation through her involvement in architectural education and design juries worldwide. Her designs are evocative and transformative, and she creates architecture that matters.

"I read somewhere that she maintains a fluid balance between energy and calm, precision and informality, experiment and comfort in her designs, studio, and life, a mantra I have been following all my life."

Eva Albarran

Nominated by Sofia Von Ellrichshausen, Pezo von Ellrichshausen

"I would like to propose Eva Albarran: a Spanish entrepreneur, living both in Paris and Madrid, who operates in the expanded, and diffuse, field of contemporary art and architecture.

"She is a solid character who has managed to solve complex productions for significant artists (such as Christian Boltaski, Felice Varini or Francis Alys). Together with her husband, they direct a refined gallery and the Solo houses program, a project that might well be read as a radical revision of the current human condition in relation to nature."

Dana Al Amiri

Nominated by Pallavi Dean, Roar

"Dana Al Amiri, the co-founder of Watab Studio, is a rising star in the male-dominated Saudi construction industry. I love her minimal pared design philosophy – practicing in a region that is infamous for opulent and OTT statements. She truly represents the next generation of regional architects that are defining Saudi's design identity."

Taller Comunal

Nominated by Tatiana Bilbao

"I would like to make Taller Comunal, which is led by Mariana Ordóñez Grajales and Jesica Amescua Carrera, my recommendation. Because for them, architecture is not a profession, it is a service to facilitate architecture to be produced by the people who inhabit it. That should be the future of our profession."

Anne Tyng

Nominated by Huang Wenjing, Open Architecture

"Anne Tyng immediately came to mind as a female architect that deserves much more recognition. Born in China in 1920 to missionary parents; a classmate of Eileen Pei and IM Pei — these two little details seem to have brought her closer to me, my being Chinese and had worked in the office that IM founded.

"Tyng was one of the first women to study architecture at Harvard Graduate School of Design; the only woman to take the architectural license test in 1949.

"It is unfortunate and unfair that people often seem to be more interested in her anecdotal affair with the iconic master Louis Kahn than her great influence on his early works — the rigour of geometry and order was very much Anne Tyng's interest and contribution. She went on to be an independent architect, theorist and educator. A true pioneering woman in the field."

V. Mitch McEwen

Nominated by Eva Franch i Gilabert

"Mitch is an architect, activist, dancer, rapper, entrepreneur, someone who has taken the lead on many occasions to make space for new ideas.

"We crossed paths several times throughout the last ten years; In 2011, during the Occupy Wall Street Movement, I organised an exhibition and a series of events at Storefront for Art and Architecture hosted by brilliant people; Mitch's workshop "How to Occupy a House in America" was one of them.

"In 2014, Mitch was one of the architects writing letters to the Mayor in the first edition in New York of the global project "Letters to the Mayor" asking Mayor Bill de Blasio: "How can New York City Housing Authority really become the Pride of Our City?" and provided some answers and ideas that still stand.

"Mitch is currently an assistant professor at Princeton University – where I am currently teaching a seminar. Her work is now on display at MoMA in New York as part of Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America."

Mónica Bertolino

Nominated by Sandra Barclay, Barclay & Crousse

"Mónica Bertolino is an architect from Córdoba, Argentina, where she lives and works as part of the Studio Bertolino-Barrado founded in 1981.

"Together with Carlos Barrado they have an excellent production of projects in different scales. In their work you understand immediately the search for good qualities in habitability, their sensibility when they intervene in the landscape, and their concern for research about materiality linked to the local traditions of construction.

"I admire and think she deserves recognition especially in her academic role where she transmits her passion and enthusiasm for architecture in an unconditional way. She is devoted to this mission!

"She participates in workshops and as invited professor in different universities in the world as well as a regular professor in the National University of Cordoba and in the Catholic University of Cordoba."

The post Twenty-two women architects and designers you should know appeared first on Dezeen.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Moulin Rouge for VOGUE!

(These are the HQ Photo Versions!)

Moulin Rouge!’s Broadway cast, photographed at Kings Theatre in Brooklyn.

Sittings Editors: Hamish Bowles, Alexandra Cronan.

Produced by 360pm. Set Design: CJ Dockery at Mary Howard Studio; Costume Designer: Catherine Zuber; Choreographer: Sonya Tayeh

Photographed by Baz Luhrmann, Vogue, July 2019

July 2019 Vogue (Online)

BAZ LUHRMANN WAS BORN to reinvent the movie musical for a new generation—which is exactly what he did in 2001 with Moulin Rouge!, his deliriously romantic mash-up, set in 1890s Paris, of La Bohème, La Traviata, and the Orpheus myth, with a soundtrack that exploded with modern-day pop songs, lavish Technicolor sets and costumes (by his wife, Catherine Martin), and a hyperkinetic cinematic style that drew on MGM musicals, MTV videos, and Bollywood spectaculars. The motto of this blatantly artificial world, served with a knowing wink (which nevertheless swept us up in its very real, very breathless emotions), could be borrowed from William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “Enough! Or too much.”

In his own way, the brilliant theater director Alex Timbers—whose work includes Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, Here Lies Love, and, most recently, Beetlejuice—was born to reinvent Moulin Rouge! for the stage, as another generation of New York audiences will discover when his electrifying, eye-popping, and blissfully over-the-top adaptation of Luhrmann’s masterpiece opens on Broadway, after a smash run in Boston, this month.

“I’ve spent my life taking classics and interpreting them in radical ways,” Luhrmann says, “so how could I not applaud someone taking a work of mine and interpreting it in a radical way? You have to interpret things for the time and place you’re in. In the end, it’s still a tragic opera, but Alex applies himself to it in such a dexterous way that there’s irony and fun and music and emotion.”

Luhrmann grew up in Herons Creek, a tiny, remote Australian town with a total of seven houses in it, where, he says, “if you didn’t have a good imagination and an ability to create worlds in your mind, you were lost.” Fortunately his family, which ran a gas station and a pig farm, also ran the local movie theater and had a black-and-white TV set (which showed exactly one channel), and Luhrmann devoured a steady diet of old movies, including musicals, with which he fell in love. His mother was a ballroom-dance instructor who started giving him lessons early, and his father insisted that Luhrmann and his siblings study painting and music. Before long he was staging little shows, performing magic tricks, making films with his father’s 8-millimeter camera, and acting in school plays.

Apparently it was the ideal upbringing to produce an artist of dazzling originality, one with a singular, idiosyncratic vision and an expansive playing field: film, theater, opera, commercials, music videos, pop songs. After the success of his first two films, Strictly Ballroom and Romeo + Juliet—both of which had healthy doses of movie-musical DNA encoded into their cinematic language—Luhrmann wanted to take on the genre itself. He and his co-writer, Craig Pearce, set their film in Belle Epoque Paris, in and around the legendary Moulin Rouge nightclub, telling a tragic love story straight out of verismo opera with the Orpheus legend—a young poet and musician travels to the underworld in search of his dead love, Eurydice, and is reunited with her only to lose her again, emerging forever changed—as its mythical underpinning.

But Luhrmann also had what he calls a “preposterous conceit” that allowed his Orpheus—a Bohemian poet named Christian, played by Ewan McGregor—to metaphorically enchant the very rocks and stones to follow him because of his voice: “When our poet opens his mouth, ‘The hills are alive with the sound of music’ comes out of it,” he says. “Whether you like The Sound of Music or not, it’s a giant hit that’s got artistic cred—so it’s a funny, concise way of saying ‘The guy has magic.’” Preposterous or not, the conceit turned the love story between McGregor’s Christian and Nicole Kidman’s doomed Satine, a nightclub star and courtesan, into a pop fantasia, giving the music its audience had grown up with—from “Your Song” to “Lady Marmalade”—an operatic grandeur.

Luhrmann had long wanted to bring Moulin Rouge! to the stage but felt that he wasn’t the right person for the job—he worried that he was too close to the material and might be overprotective of it. Enter Alex Timbers, 40, a downtown wunderkind who has brought the cheeky, postmodern spirit of his theater company Les Freres Corbusier to Broadway and shares with Luhrmann a restlessly playful and inventive mise-en-scène. “When I saw Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, I could tell that his aesthetic and the way he told a story—very high-energy, very theatrical, ironic but also moving—had a certain kinship with mine,” Luhrmann says. “And after I met him, I knew that he would have his own interpretation but also understand the language of the film.”

The biggest challenge Timbers and his team faced was how to bring the film’s hypercinematic exuberance alive on a stage. “We had to create a visceral and kinetic excitement using an entirely theatrical vocabulary,” Timbers says. “We don’t have any of those virtuosic techniques like close-ups and Steadicam and music video–style editing, but you want the show to be able to leap over the footlights—emotionally, but also as a spectacle. So we use a lot of techniques to do that.”

Do they ever. From the moment you enter the theater, it’s clear that Timbers has realized his mandate to make the show—which he’s been working on for the past six years—“360.” It’s as if you’ve walked into the Moulin Rouge itself, courtesy of the gorgeously overwhelming set (by Derek McLane) that greets you: There are hearts within hearts, chandeliers, the stage flanked by a windmill on one side and an elephant on the other. Then out come the corset-clad boys and girls of the night (who come in all colors, shapes, and sizes) and the fashionable members of the Parisian demimonde in Catherine Zuber’s fabulous costumes. The next thing you know, “Four Bad Ass Chicks from the Moulin Rouge,” as the script identifies them—propelled onstage by Sonya Tayeh’s wildly exuberant choreography—are belting “Hey sista, go sista, soul sista, flow sista,” and we’re off to the races. “I wanted to build this exotic, intoxicating world that felt beautiful and dangerous and gritty and sexy,” Timbers says. “It felt really important for the sets and the costumes to use period elements, and for us to be ruthless about that, but to put them in a form that feels contemporary and surprising.”

The seven-time Tony-winning costume designer Zuber (The King and I, My Fair Lady) has done that and then some, tipping her hat to Catherine Martin’s designs for the film without imitating them. She’s even managed to design Belle Epoque finery that allows the dancers the freedom of movement to execute Tayeh’s propulsive choreography. Zuber is also a master of using costumes to reveal character and situation, as with the ornate gown she designed for Satine after she becomes the Duke’s courtesan and enters his glittering world. Inspired by designs from John Galliano’s 2006 couture collection, it features a bodice that looks like a cage and three rows of lacing down the back. “It’s almost like she’s a prisoner,” Zuber says.

Playing Satine this time around is Karen Olivo (West Side Story, Hamilton), who brings very different qualities to the role than Kidman, both physical (Olivo is a woman of color) and temperamental (desperate, determined, and down-to-earth, as opposed to ethereal). Aaron Tveit (Next to Normal, Catch Me if You Can), meanwhile, sings like a dream and brings the requisite dewy idealism to the naive Christian, but with a hint of something edgier.

The story is very much the same as the film’s: Satine is the star attraction at the Moulin Rouge, owned by the rapacious Harold Zidler (Danny Burstein), who is in financial hot water and in danger of losing the club. Christian and Satine meet and fall head over heels, but she has been promised by Zidler to the villainous Duke (Tam Mutu), who can give her the bejeweled life she’s always dreamed of, forcing her to choose between that and true love. Meanwhile, Christian and his pals Santiago and Toulouse-Lautrec (Ricky Rojas and Sahr Ngaujah) are writing a show, bankrolled by the Duke, that is meant to save the Moulin Rouge from going under. Then, of course, Satine has this persistent cough and . . . well, you know.

The big difference in terms of the storytelling is that book writer John Logan (Red) has fleshed out and deepened the characters and the relationships between them. “We looked at the major characters, asked what their backstories were, and tried to figure out how grounded they could possibly be in psychological realism and yet still be heightened in that way that musical theater demands,” Logan says. “How did Satine get to be this sparkling diamond—and what’s the price she’s paid along the way?”

But the boldest change—and in many ways the heart of the show—is in the new songs, which give Moulin Rouge! fresh emotional resonance (and whip the crowd into a frenzy). Along with the familiar Bowie, Madonna, and Elton John tunes, expect to hear from the likes of Outkast, Sia, Beyoncé, Fun, Adele, and Lorde, to name but a few (there are more than 70 songs in the show). To curate Moulin Rouge!’s dizzying playlist, Timbers, Logan, and music director/genius Justin Levine holed up in a Times Square hotel room with a digital keyboard, dredged up their musical memories, and took note of what worked. Their taste is impeccable, whether using a song for its sheer exuberance, as with a rousing version of Lady Gaga’s “Bad Romance,” or to reveal a character’s inner desires, as Satine does with Katy Perry’s “Firework.”

Logan has been blown away to see how powerfully audiences have connected with the show—and the songs. “I went to a wedding recently, and when the dancing started, I heard half our score being played, which was wild,” he says. “And when you see audience members respond to the songs—‘They’re using thatsong? Oh, my God! No way!’—you can feel how excited they are. It’s an experience I’ve never had before. It’s magic.”

#moulin rouge#aaron tveit#karen olivo#danny burstein#vogue#Baz Lurhmann#moulin rouge broadway#moulin rouge musical#vogue magazine#articles#features#ricky rojas#tam mutu#sahr ngaujah#robyn hurder#jacqueline b arnold#jeigh madjus#holly james

333 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evaluation

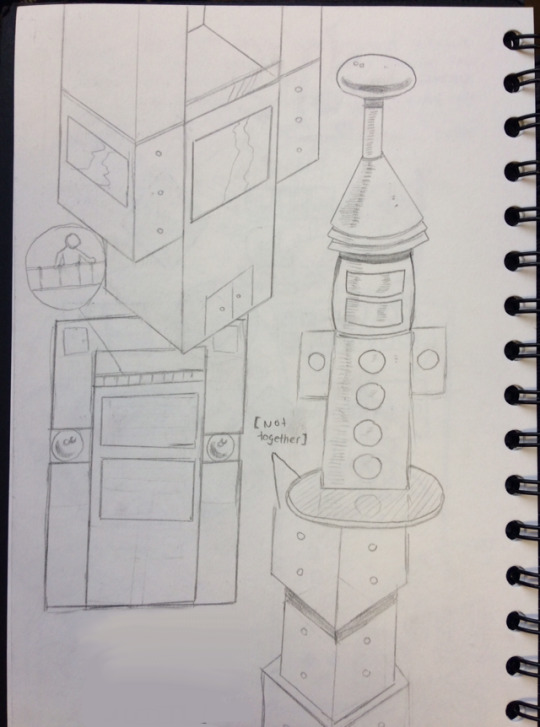

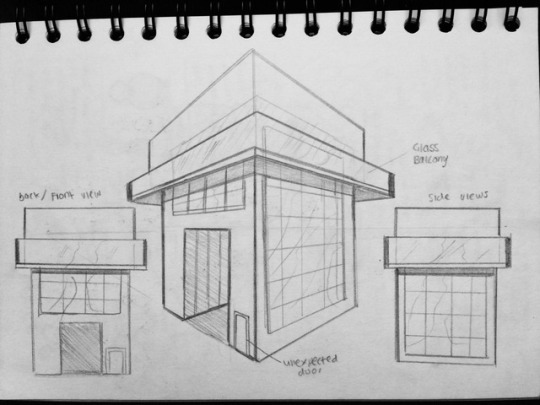

Fabrication another possible outcome:

In the revisit of the fabrication project, I explored other disasters which impact the way people live and their accommodation. I began to explore war zones through Google, Pinterest and mainstream media. Most of the time whole cities are wiped out due to bombing, they take very long to clean out and rebuild this causes a high level of homelessness. I wanted to come up with a design of a building that can be achieved without having to clean and rebuild all of the city’s streets and existing buildings. Councils can have this installed in one area with less destruction while cleaning the rest of the city.

Throughout my research, I came across Brutalist architecture which was popular in the1950’s. It is recognised for the use of rough, unfinished materials for the exterior of buildings and consisted of straight lines, unusual shapes, and small windows. Socialist principles influenced the utilitarian, low-cost social housing. After the Second World War Le Corbusier accomplished his Tower Block which he’d been designing since the ’20s. The first two were built in Paris and Marseille and housed around 1600 people.

I learned a lot about how I work best when I am motivated is when it is easier for me to work and enjoy it. Due to lockdown, there was confusion as to which pieces of our work will be marked and how grades will be established. This made me less keen to work as I felt like when I was working hard at one project, I would receive an email stating that it will not be marked or count towards my grade. I found it very hard to enjoy the work I was doing due to the atmosphere. I was didn’t feel creative, I stopped thinking about design and my love for it for a long time which made me question my choices and career. There was a period where I couldn’t do any of the work because I just wasn’t sure if this (architecture) is what I want to do for the rest of my life. This was very frustrating as my career has always been the only thing I’m sure of. As an easily distracted procrastinator, working at home was very challenging. There wasn’t much to inspire me in terms of giving me new ideas or ways of looking at the projects, nor inspire me to continue doing the work. At college, in a classroom, everyone is being creative and bouncing off of each other’s energy. I could ask one question and start a discussion which results in lots of new concepts for me. Whereas at home I don’t have that so my energy slowly faded away. It was also very hard to find a quiet time and place, with a big family and kids playing all the time. This with my lack of motivation made me very uninterested in doing the work. It was very unhealthy for my mental health because my career was always my main drive and I lost that. I felt very confused and anxious for a long time.

I decided that no matter what I want to do with my career I needed to do my best in the course now and whatever comes after that is my choice. I began to only work when my family were asleep. Sometimes that meant waking up at 4 am or sleeping in and staying up all night. Thankfully, this worked out well in terms of getting the work finished. I think I could’ve done much better if I had used my time more wisely and was more motivated.

The most attractive task was drawing the exterior of the building in perspective. It took about 3-4 attempts but once I began to work on the final one it was very enjoyable. It felt like a break from work even though it was time-consuming. I think it is very satisfying because the drawing looks messy and there are lines everywhere until you add pen lines and colour then it all becomes clear within minutes. The most unattractive work I did was making the playdough for primary inspiration. I used flour, cooking oil and food colour. I didn’t like the texture of it when mixing the ingredients. The result was very good though, I couldn’t go to buy play dough at the time but I needed it that day to make sure I don’t forget to do it.

The research went well, there were many examples of social housing in styles and expenses. Most existing structures saved as inspiration but were too luxurious to be a reality for a post-war city.

The thing that went very badly was my attempt to find software that would allow me to produce a realistic-looking design to deliver my idea in a better way. They were all made for advanced architects, although the tutorials show other results which looked like what I wanted, I didn’t know how to achieve them.

My research gave me a lot in understanding the concept of what I was trying to achieve myself. There are many different examples of social housing. Also, it shows me that my idea may be original in what it is trying to achieve. I would like to make it a habit to use books as magazines as research tools, not just the internet.

The limitations in this project made it very unique, I couldn’t experiment with any materials or make models to help me see my design in a new light which would allow me to alter things and point out design flaws.

Self-review

My research was sufficient to help me come up with different designs and concepts. It was varied enough for me to take a piece from each example and implement it into my design. The large amount of it though meant that I couldn’t critically analyse it. This was also mainly due to poor time management, I didn’t want to make lists and times plans as I had in previous projects because there were a lot of changes in what our concentration should be on. I felt like if I made a checklist and didn’t get the chance to complete it I was more discouraged to do the work. The main problem solving I had to do was on my attitude towards finishing the project. I think work is now mediocre because of this, which I don’t particularly like.

The only practical skills used for this project were attempting to draw using different mediums. It was challenging trying to render the design using software that was very new to me but I made many attempts. Unfortunately, none are presentable in my opinion.

I made many attempts to put the drawing in situ but I couldn’t find any suitable images. There were a few places I had in mind where I could’ve taken photographs of my own but I couldn’t go as it seemed unnecessary. When drawing the outline I made the lines as clean and think as possible to make the process easier.

I believe this building fits into the brutalist style of architecture with the bright element. The concrete floors and harsh corners that face the outside contrasted by the round pillars give the building more elements. It doesn’t completely fall into the movement but has elements of it.

Bibliography

https://medium.com/projexity-blog/architecture-meets-social-engagement-in-5-awesome-projects-af283bba616b

https://www.archdaily.com/933053/best-unbuilt-architecture-7-submitted-proposals-exploring-diverse-programs

https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/architects-lounge/a455-15-buildings-that-reflect-contemporary-nature-of-social-architecture/

https://www.rasmussen.edu/degrees/design/blog/9-types-of-design-jobs-for-creative-people/

https://targetjobs.co.uk/careers-advice/career-planning/273051-the-top-10-skills-thatll-get-you-a-job-when-you-graduate

https://www.indeed.co.uk/?from=gnav-jobsearch--jasx

https://www.whatuni.com

https://www.ucas.com

https://www.archdaily.com

https://www.dezeen.com/2014/09/15/le-corbusier-unite-d-habitation-cite-radieuse-marseille-brutalist-architecture/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brutalist_architecture

0 notes

Text

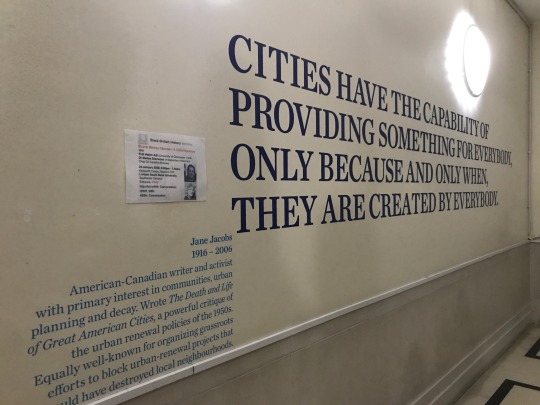

Photo text: "Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because and only when, they are created by everybody."

"- Jane Jacobs 1916-2006, American-Canadian writer and activist with primary interest in communities, urban planning and decay. Wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities, a powerful critique of the urban renewal policies of the 1950s. Equally well-know for organizing grassroots efforts to block urban renewal projects that would have destroyed local neighborhoods. "

I never got around to reading Jane Jacobs, though I've skimmed enough references to her to appreciate her view of the local community as the interactions (and potential for interactions) amongst neighbors. While Le Corbusier was in favor of making the city into big towering apartment blocks that could provide as much housing as possible with limited shared amenities, it seems like her definition of the community unit was a lot more in line with how real life shakes down.

Friday's class mentioned going into history to find inspiration for the future, in a way anyway, so it strikes me that the present complications about "smart city" echo the old question of how do you build a city for the people? How can we design for inhabitants in a way that uses citizens beyond strings of data or bodies to be stored? Maybe I should do a bit of sparknotes research into Jane Jacobs's theories and how she conceptualized community interactions. We were talking about the circular economy and it reminds me of my own experiences with feeling like being part of a community. For example:

When I was living in New York, I really loved keeping an eye out for furniture in the piles of trash outside homes the night before Trash Day. (Rarely did I ever take anything home, since the threat of bed bugs is omnipresent.) But one night, I saw a perfect frosted glass door lying on the sidewalk amongst pieces of what looked like a dismantled down IKEA wardrobe. It was about 90 inches tall, taller than my apartment ceiling, and the length of my arm.

Greed gripped me and quickly I went home and got one of my roommates to help me carry this huge glass door home. I was worried that taking it would ruin someone else's future wardrobe set, but I also really wanted to use it for projection or puppetry or art or something. I was also worried that since it was such a perfect glass door, I should be paying someone for the honor of taking it from their trash, so I wanted to escape with it quickly.

While we were trying to maneuver the door out of the pile of trash, an older woman had come out from the apartment building and watched us struggle. For some reason, my nervousness about stealing this glass door made me think it belonged to her--and maybe it did, since she noticed me nervously looking at her and went "take it!"

"It's such a nice door! Thank you so much!" I was incoherent with gratitude. I had never seen this woman in my life but I really wanted to be neighbors with her in that moment, share our lives, form a community, repay her for this boon. My roommate and I made off with the door and I never saw this woman again. The door sat in our living room, propped against the wall, unused for another two years.

When it came time to move out, I was trying to freecycle all my stuff and for some reason, I put the door up too. Who'd want a random glass door? But it was perfect and I really, really wanted to hold onto it but there was no way I could throw it back onto the street and not a chance I could take it with me.

It was the first thing to claimed. The person didn't mention why they wanted it, so my roommates and I made up many scenarios, all of them possible and ridiculous.

I got a roommate to haul it downstairs with me, and when the time came a young woman hopped out of a SUV. We struggled getting the door into her car. I managed to ask her why she wanted it. Turns out this door would become a whiteboard for her young students to draw on. What a good reason! Ultimately we managed to balance it precariously over her passenger side seats and it barely fit, but she slammed her trunk and drove away.

And so I said goodbye to the glass door, which is now hopefully living a good third(?) life.

I think this whole process was hilarious but also I love this memory because it's so rare. What if this whole process was ordinary? What if we naturally expected our items to transform, and to change ownership?

There was a great car ad a few years ago when the owner of the car asks a nosy stranger, "who are you?" "I'm the next owner," the stranger replies.

What if we talked about product lifecycles like life stories? Things would be much less disposable, surely, and maybe there would also be stronger community ties. Freecycle was good, I enjoyed the brief moment of intersection I had with this teacher, but what if I could call her up and ask her how it went? How my dear trash door is doing? What if the door could talk back to me?

What if I could call up the lady I had taken this door from, and let her know that I've also paid it forward? What if I could take more trash off the street and know that it's not infested with bed bugs, have guarantees and accountability? I really love it when I see trash that have a small message taped on: I work!

Again, this interest in histories and artifacts could be interesting if the stories were told from the voice of the object. (Would objects have an objective voice?) At the very least, I would be interested in a world where their possessors could talk to each other, trace the intersections of their lives.

0 notes

Text

The 25 Rooms That Influence the Way We Design

The 25 Rooms That Influence the Way We Design

https://ift.tt/38uI6hs

Continue reading the main story

Credit...Video by Scott J. Ross

The 25 Rooms That Influence the Way We Design

Three designers, two journalists and an interiors photographer gathered at The New York Times to make a list of history’s most enduring and significant spaces. Here are the results.

On an October afternoon, our six-person jury — Tom Delavan, the design and interiors director of T Magazine; Gabriel Hendifar, the creative director of the Manhattan-based lighting and design studio Apparatus; the architect Toshiko Mori; the architect and designer Daniel Romualdez; the veteran design journalist Suzanne Slesin; and the interiors photographer Simon Watson — assembled in a featureless conference room at The New York Times to discuss the most influential rooms of all time. By that, we meant “influential” in its truest sense. We wanted the jury to identify the spaces that not only changed the way we live but also changed the way we see, places — whether pleasing, provocative or completely novel for their eras — that not only informed our panelists’ individual practices as designers and documenters but also challenged how we all, as humans, think about beauty, strangeness, originality, décor, proportion, furnishings, art and the multivalent connections therein that define memorable rooms: ones that, above all, offer a new kind of visual lexicon. These are rooms, in other words, that have influenced and inspired interior design throughout the decades, shaping how our mind identifies and assesses a space, any space.

Image

From left: Tom Delavan, Toshiko Mori, Daniel Romualdez, Suzanne Slesin, Gabriel Hendifar and Simon Watson, photographed at The New York Times on Oct. 14, 2019.Credit...Sean Donnola

No one was expecting unanimity; if taste is individual, then discord among this cohort was inevitable. And yet we had asked each of them to nominate their 10 to 15 favorite rooms ahead of time, which the group would whittle to a list of 25. The overlaps were obvious front-runners: Four people chose the soaring, glass-walled sitting area of Pierre Chareau’s Maison de Verre, built in Paris in 1932, while Cy Twombly’s objet-filled 1960s living room in his Roman apartment, Rem Koolhaas’s elevator-cum-office built in 1998 for a disabled client in Bordeaux and Yves Saint Laurent’s art-covered 1970s Parisian salon were also submitted by several panelists. A lively conversation ensued for nearly three hours: What’s more important, the architecture or the design? Are the best spaces dictated by the people who inhabit them? The designers who create them? The period they reflect? Or some magical alchemy of all those things? Should public areas like hotels and restaurants be given as much weight as private, residential ones? And, actually, what is a room?

That last question animated the conversation from beginning to end, as each of our experts made arguments both concrete and philosophical about the human need to gather and connect in enclosed space, sometimes with the intimacy-creating aid of walls and ceilings, but other times not. (We drew the line on gardens — even ones with hedge walls — which everyone decided didn’t qualify.) By the end, we had narrowed upon a mutually satisfying definition of what makes a room and a list of about three dozen worthy examples, the images of which we laid out on a massive conference table, assessing them for final inclusion: Do we have too many museums and, speaking of, is the spiraling rotunda of New York’s Guggenheim more of a room or a building unto itself? Is the living room of the Finnish furniture designer Alvar Aalto a better representation of midcentury Scandinavian Modernism than that of the Danish furniture designer Finn Juhl? Where are all the female-led projects? (“We have to remember that architecture, like many industries, was male-dominated for much of history,” Delavan said. “And the field of interior design — while originally led by women, though now more evenly split between genders — is only a century or so old.”)

Eventually, consensus was reached, though that doesn’t mean the list is necessarily finished or complete: The royal “we” in this story’s headline was, in many cases, applied by our panelists to their own work, the way that they think about design while largely practicing in North America and Europe, which unfortunately means that entire continents such as South America and Africa weren’t under consideration as much as they would have been with another group. There’s a heavy emphasis on contemporary projects, places that everyone had seen with their own eyes. (“Just blame it on the editors,” Romualdez joked, to which Slesin responded, “What’s amazing, if we had to do this tomorrow, is how different it would be.”) So the result that follows — which is ordered chronologically, from oldest to newest — is, at its very least, one history of design in the West on one day from one group of highly opinionated people, all of whom would probably have rather found themselves in any of the rooms below. — KURT SOLLER

This conversation has been edited and condensed. The room summaries are by Nancy Hass.

1. Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England (circa 1600 B.C., architects unknown)

It took Neolithic builders nearly 1,500 years to complete Stonehenge, the outdoor enclosure of nearly 100 enormous upright stones on Salisbury Plain in the south of England. The origin of the structure, which is thought to have been a burial ground or perhaps a place of pilgrimage — the stones are aligned to frame sunrise during summer solstice and sunset during winter solstice — defies logic: The iconic 30-foot-tall three-piece sandstone pillars that stand in the center can be traced to local quarries, but how did a civilization without the wheel transport the inner ring of bluestones, some weighing four tons, from their origin point 200 miles away in Wales? Thought to have been finished around 1600 B.C., over the eons Stonehenge has been attributed to the ancient Celtic high priests called druids and the Arthurian wizard Merlin. But modern historians and archaeologists largely agree that a series of indigenous British tribes worked on the site in stages, over hundreds of years, each culture gaining technological sophistication through the centuries, creating an open-air chamber that stands as an indelible template for enclosure, space and ambitious monumentality.

Tom Delavan: My colleague Kurt and I were discussing what qualifies as a room, and we thought, “Well, a room has walls, or something that could define a wall. But does it need to have a ceiling?”

Simon Watson: For me, a room is a place for people to inhabit together in solidarity, I suppose.

TD: So residential, you’re saying?

SW: Not necessarily. It’s a place where people can gather; it’s what we humans do. I tried to go back as far as I could, and Stonehenge seemed like an obvious choice. I’m not sure if we know much about it, but what we do know is that it was a space where people gathered: Whether they prayed or whether they had conversations about their day, it was a place where people came together. And, for me, that was the definition of a room. It doesn’t have a ceiling. And I don’t think the difference stands in the make of walls, but it creates a space.

Gabriel Hendifar: Or is it just about some spatial organization that communicates intention, whether that intention has a ceiling or not? A room is something that’s been organized to serve some function, whether that is spiritual or shelter, residential or commercial.

SW: And you can go forward in history from Stonehenge to the Pantheon, which is one of the greatest rooms in the world. I’m not suggesting that the Pantheon came from Stonehenge, but rather that the circle is a humanist form we understand. It is the shape that creates a togetherness, in a way. It’s instinctual.

Toshiko Mori: Well, also, Stonehenge has a reference to astronomy. It’s human enclosure, with references to the world outside earth. So, the ceiling in this case is a sky. I think that’s the beauty with it, that it actually exists between ground and sky.

2. The Pantheon in Rome (125 A.D.; architects unknown)

The Roman Pantheon is not only the world’s best-preserved Classical building — it was completed by the emperor Hadrian on the site of an earlier structure of the same name that was probably a sanctuary — but is also likely the first in which the interior, not the exterior, is the focus: It was a precursor to the elaborate decoration of public spaces in later centuries, as well as a model of perfect balance. While its portico, reached by wide steps of Numidian yellow marble, was made in classically Greek style (squared off, with granite columns) once you enter the circular part of the building, you find a shrine to the motifs and mathematical obsessions of the Roman Empire. The rotunda is 142 feet in both diameter and height — a perfect hemisphere — with a 27-foot-wide oculus at the top of the domed ceiling. The dome itself is made of a porous type of limestone, like pumice, mixed with concrete, and has five rings of 28 rectangular coffers. Altered over the eras by successive rulers, including Pope Urban VIII, who in 1626 removed the original bronze girders from the porch roof to make them into cannons, the Pantheon’s architectural and decorative influence cannot be overstated: Thomas Jefferson’s 1826 library at the University of Virginia is one of many obvious homages.

3. The Shokin-tei tea pavilion in Kyoto (circa early 17th century; architects unknown)

The Katsura Imperial Villa near Kyoto, built in the early 17th century, profoundly influenced architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, both of whom spent time in Japan. And with good reason: The 16-acre property, with many outbuildings and exquisite gardens, is a clear expression of how Zen Buddhism’s graceful influence is woven through Japanese culture and design — and is a vivid illustration of why those aesthetic codes still feel utterly contemporary. There are several free-standing tea pavilions on the property, all made to amplify a sense of pureness, reverence and isolation (each celebrates a different season and allows the gardens to be seen from various angles), but Shokin-tei, the tribute to winter, is the one that stands out for its unexpected modernity. With a thatched roof and three sides that face the property’s large pond, it’s notable for the blue-and-white checkered handmade paper that covers a central alcove and sliding doors. The loggia is held up by three oak logs, left natural with their bark intact. Rustic and bold, the teahouse is pleasingly geometric, a hallmark of traditional Japanese architecture.

Kurt Soller: How many of your choices were influenced by having seen these places in real life? Tom made this great point about how, for many people, most of these spaces only exist through pictures.

Suzanne Slesin: That’s why I included the Katsura teahouse, because I’d been there. I went on a tour, and I think we were the only Westerners. It was pouring rain. You’re wearing this translation earpiece, and you go around and the guide was talking, talking, talking in Japanese, and everybody was taking it very seriously, and then the translation was just: “teahouse.” So I just took the picture and I stood there and I thought, “It’s really beautiful, but I’d like to know more about it.”

TM: It’s incredibly influential. A literary reference. So that’s why the Japanese guide would go on and on and on to talk about —

SS: We understood nothing. But to me, this was extraordinary: Of course, Japanese interiors are influential, but this blue and white, I mean, anybody could do that today. And it would be amazing.

TM: The Bauhaus school [in early 20th-century Germany] had seen it. I have to be a little careful about this immediate link because it’s been an argument, a scholarly argument. But it’s very interesting to think about.

4. The parlors of Georgian homes in the United Kingdom (circa 1714-1830; various architects)

There is no perfect room, of course, but the parlor of the typical Georgian home — built throughout London and Edinburgh during the reigns of King George I through King George IV — may come close. The rooms are large, but not in the cavernous, ill-planned way of a McMansion or a billionaire’s high-rise penthouse on Central Park: They are, instead, models of proportion. Usually square, with ceilings around 16 feet high, the parlors’ symmetry was based on the Classical architecture of Rome and Greece, filtered through the lens of the Renaissance but scaled down to accommodate a single family. Unlike the neo-Gothic revival, which began as early as the mid-18th century, or the late Victorian period at the end of that century, both of which prized ornament, there was a spareness to Georgian style, which makes it feel modern today. Windows, placed with mathematical precision, were large and often shuttered — Georgian builders seemed to understand that in the late afternoon, taking tea, one might want to ease gently into the dusk.

SW: The Georgians started this idea of creating very livable proportions in rooms. When you go through them, the scale is huge, with vast windows, but you feel completely comfortable, because the proportions are so perfect. So these big spaces become calm, wonderful places to be in, to live in and socialize with your family or your friends.

KS: Has it influenced how people live now?

Daniel Romualdez: I think they bring the influence.

SW: I think people miss it. I’m looking around me [here in Midtown Manhattan] and I happen to see these vast skyscrapers going up and people living in these enormous spaces. I’ve been in them. You walk in and you think, “How could you live here?” The proportions are wrong. First of all, you need sunglasses all day long.

DR: All that glass!

5. Pierre-François-Henri Labrouste’s reading room at the Sainte-Geneviève Library in Paris (1851)

The Sainte-Geneviève Library, in the Fifth Arrondissement, has roots dating back to the sixth-century manuscript collection of the Abbey of Sainte-Geneviève, though its soaring reading room was built over 13 years, starting in 1838, by the Beaux-Arts architect Pierre-François-Henri Labrouste, who had spent his early career mastering the use of iron in grand railway stations and thus was a virtuoso at evoking grandeur. The nearly 20,000-square-foot, two-story structure is defined by exposed cast-iron arches, suspended over iron columns like parachutes billowing above a giant classical arena. The room, which is now part of Paris’s university system, stands as one of the finest neo-Classical interiors in Europe, influencing the Gothic Revival that swept late 19th-century France as well as the innovative spirit of the architect Louis Sullivan, who at the turn of the 20th century pioneered the use of iron and reinforced concrete in the American skyscraper.

TD: I bet it’s such a nice place to be, between the light and the space.

SW: But it’s also so delicately supported.

TM: Yes, because of the cast-iron work. So it’s a new technology, but within tradition. The motifs of all the cast-iron elements are plants, so it refers to nature, which softens the technological aspect: Otherwise they could have made it look like trusses, but they didn’t. There’s also a visual relationship to the books’ paper, which comes from plants. This influenced the Boston Public Library, the Butler Library at Columbia University, the Doe Library at U.C. Berkeley and others, so this whole idea of a collective reading room is an important example.

6. The Bloomsbury Group’s studio at Charleston in Sussex, England (circa early 20th century)

Inspired by the bright, fluid figuration and sharp abstraction of Post-Impressionists including Gauguin and Matisse, who led the way to High Modernism after World War I, the visual artists of the Bloomsbury Group ran wild at Charleston, the Sussex, England, farmhouse where the married painters Vanessa and Clive Bell and Vanessa’s lover Duncan Grant lived for decades. Virtually every surface in the house, a way station for intellectual bohemians including Vanessa Bell’s sister, the novelist Virginia Woolf, is covered in joyous drawings. In the living room, barely clad classical figures dance across the hearth, and books spill out from shelves. The house, preserved after Grant’s death in 1978, is the embodiment of the revolution that shook the art and design world, its handcrafted ethos driven by the class-driven conflict that took root in England between the wars.

SS: The Bloomsbury rooms combined all the arts together, and this was both unique and very influential. They also represent a coming together of all the arts in a place and time that, although it has passed, is very current in terms of how people engage with design.

KS: And the craft of it all, too, the idea that [the Bloomsbury-adjacent guild known as] the Omega Workshops seems so visually relevant now.

SS: Exactly. I think that’s something people are talking about now. [A few decades ago,] I remember knowing about this and thinking, “Oh, it doesn’t suit my Modernist sensibility. It’s cluttered.” But now I’m looking at it very differently, and I think it’s both charming and bohemian, which is very attractive.

DR: Why did that change?

SS: Well, things happen in life. Some of the things that you like 30 or 40 years ago, you’re less interested in, or you get bored with them. Even well-known designers, like you, Daniel, your style changes. It depends on your clients, but also the way you feel.

DR: Yeah. What persists for you?

SS: I still love Minimalism and Modernism.

DR: Do you think the Modernists’ influence is waning? You know, 30 years ago, when I was in architecture school, that’s all we talked about.

TD: Since I started working at magazines [in the early 2000s], Modernism has basically been watered down. It’s sort of softer; it’s not about an absence of decoration, or anything similarly social or political. It’s just about simplicity.

SW: It’s become more cushy and comfortable.

DR: But don’t you think it’s also, like, a status symbol? A buzzword?

SW: Yes, in every single place in the world.

DR: And you just think, “Oh, I know about Modernism. I’m going to do that even though everything about this room has nothing to do with it.”

7. Jean-Michel Frank’s living room for Marie-Laure de Noailles’s hôtel particulier in Paris (circa 1925)

The Jazz-era Parisian arts patron Marie-Laure de Noailles blithely disregarded convention. She and her husband, Charles, underwrote the Dada-inflected films of Luis Buñuel and Man Ray and bought arms for the anti-Franco forces. Their 16th Arrondissement apartment sparked the career of Jean-Michel Frank, an interior designer who stripped away the early-18th-century moldings from the vast rooms and squared off the giant opening between them. The walls of the apartment (which was returned to its ornate origins by the designer Philippe Starck in 2003 for the Musée Baccarat) were covered in parchment panels hung with paintings by Dalí, Picasso and Miró. And the severe living room furniture that Frank made for the couple continues to inspire contemporary design; created from lush materials including shagreen and mica, the pieces combine geometric discipline with the mark of the artisan’s hand.

8. Pierre Chareau’s salon for Jean Dalsace’s Maison de Verre in Paris (1932)

Bathed in sunlight during the day and lit at night with a phosphorescent lantern glow, the Maison de Verre may well be Paris’s most radical residence. Resembling a box made of glass blocks capped by a single traditional apartment, it was commissioned in the late 1920s by Jean Dalsace, a gynecologist who bought an 18th-century Left Bank hotel, determined to reinvent it as a Modernist mansion. Unable to evict the top-floor tenant, he built around her. The architect, Pierre Chareau, conceived the edifice as a series of interlocking forms, with the doctor’s office on the first floor and two private levels above. Simultaneously labyrinthine and airy, with several sets of stairs and a double-height salon behind the monumental glass wall, it has been compared in impact to Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s Villa Savoye (1931) on the outskirts of the city. But unlike that imposing International Style monolith of reinforced concrete, the Maison de Verre possesses a lyrical delicacy owing to the work of the iron artisan Louis Dalbet, who created such touches as perforated mechanical screens to separate spaces and a rolling steel-pipe library ladder with wood inlays. After remaining in the Dalsace family for more than 70 years, the house was bought in 2005 by the history-obsessed American collector Robert M. Rubin, who meticulously restored it.

KS: The Maison de Verre was the most submitted project among our panelists: Four of you chose it —

DR: If I remembered, I would have put it on my list.

GH: Me too.

SS: I mean, it has everything: It has a new structure, it looks to the future, it has furniture that is not just traditional but also modern. Everything about that house — the traffic patterns, the materials, the siding of it, the way it’s used — is really a 20th-century development. And it’s beautiful. I mean, I think it’s beautiful.

DR: It changed the way we designed, you know, these glass-wall houses. The coziness. The multilevel living room.

TD: It’s very comfortable, which isn’t always the case for things that are modern.

9. Finn Juhl’s living room at his home in Charlottenlund, Denmark (1942)