#nanboku tsuruya

Audio

It is yet another TOKAIDO YOTSUYA KAIDAN (1959), but this time from experienced horror director Nobuo Nakagawa!

Balancing a return to its kabuki roots with a forward-looking use of colour and surrealism, this horror takes your hosts by storm! The film stars Shigeru Amachi, Katsuko Wakasugi and Shuntaro Emi.

Context setting 00:00; Synopsis 28:53; Discussion 44:01; Ranking 1:00:54

#podcast#horror#japanese horror#yotsuya kaidan#tokaido yotsuya kaidan#nobuo nakagawa#shigeru amachi#katsuko wakasugi#shuntaro emi#ryuzaburo nakamura#noriko kitazawa#jun otomo#masayoshi onuki#yoshihiro ishikawa#nanboku tsuruya#mitsugu okura#tadashi nishimoto#shintoho#the ghost of yotsuya

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談), ukiyo-e by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The story of Oiwa and Tamiya Iemon is a tale of betrayal, murder and ghostly revenge. Arguably the most famous Japanese ghost story of all time, it has been adapted for film over 30 times and continues to be an influence on Japanese horror today. Written in 1825 by Tsuruya Nanboku IV as a kabuki play, the original title was Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan (東海道四谷怪談, Ghost Story of Yotsuya in Tokaido). It is now generally shortened, and loosely translates as Ghost Story of Yotsuya.

First staged in July 1825, Yotsuya Kaidan appeared at the Nakamuraza Theater in Edo (the former name of present-day Tokyo) as a double-feature with the immensely popular Kanadehon Chushingura. Normally, with a Kabuki double-feature, the first play is staged in its entirety, followed by the second play. However, in the case of Yotsuya Kaidan it was decided to interweave the two dramas, with a full staging on two days: the first day started with Kanadehon Chushingura from Act I to Act VI, followed by Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan from Act I to Act III. The following day started with the Onbo canal scene, followed by Kanadehon Chushingura from Act VII to Act XI, then came Act IV and Act V of Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan to conclude the program.

The play was incredibly successful, and forced the producers to schedule extra out-of-season performances to meet demand. The story tapped into people’s fears by bringing the ghosts of Japan out of the temples and aristocrats' mansions and into the home of common people, the exact type of people who were the audience of his theater.

source

#yotsuya kaidan#ghost story#japanese folklore#japanese ghost story#ukiyo-e#kabuki#utagawa kuniyoshi#japan art#japan#japanology

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ken Uehara and Kinuyo Tanaka in Yotsuya Kaidan (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1949)

Cast: Kinuyo Tanaka, Ken Uehara, Osamu Takizawa, Keiji Sada, Hisako Yamane, Jukichi Uno, Aizo Tamashima, Choko Iida. Screenplay: Eijiro Hisaita, Masaki Kobayashi, based on a play by Nanboku Tsuruya. Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda. Production design: Isamu Motoki.

Yotsuya Kaidan is one of the most famous Japanese ghost stories, put in classic form in the kabuki drama written by Nanboku Tsuruya in 1825. But in adapting the tale of a ronin, a masterless samurai, pursued by the vengeful phantom of the wife he murdered, Keisuke Kinoshita and his screenwriters, Eijiro Hisaita and the uncredited Masaki Kobayashi, jettisoned the supernatural elements to turn it into a psychological drama with overtones of Shakespeare tragedy: the ambition of Macbeth and the jealousy of Othello, abetted by an Iago-like villain. The ronin of Kinoshita's film, Iemon Tamiya (Ken Uehara), was dismissed by his former master for failing to guard the storehouse from a thief; he now ekes out a living with his wife, Oiwa (Kinuyo Tanaka), making and selling umbrellas. But while drowning his sorrows in sake one evening, he is approached by Naosuke (Osamu Takizawa), who plants in him the idea of wooing the wealthy Oume (Hisako Yamane), whose father has the connections that would enable him to find a master and restore his status as a samurai. Naosuke also plots with Kohei (Keiji Sada), with whom he served some jail time, to woo Oiwa, with whom Kohei has been infatuated since the days when she worked in a teahouse. Kohei's attentions to Oiwa arouse Iemon's jealousy, which Naosuke plays upon. As the prospect of marrying Oume becomes more likely, Iemon is given a poison to use on Oiwa, but he's initially reluctant to go that far. When Oiwa accidentally scalds her face, producing a horrible disfigurement, Naosuke provides an "ointment" that puts her in terrible pain and Iemon administers the poison. In the turmoil that follows Oiwa's death, Naosuke also kills Kohei. Freed to marry Oume, Iemon finds himself tormented by a guilty conscience, and when he learns that Naosuke was the one who robbed the storehouse that led to Iemon's dismissal by his former master, he turns on the conspirator. A fiery conclusion results. Kinoshita released the film in two parts, the first running for 85 minutes, the second for 73 minutes. Part I is more tightly controlled, efficiently introducing its characters -- there are lots of secondary ones, including Oiwa's sister, Osode (also played by Tanaka), and her husband, Yomoshichi (Jukichi Uno), who provide a kind of grounding in normal life. Kinoshita is not as successful at marshaling all of the secondary plots in Part II, and I tend to blame the director's tendency to sentimentalize, including the search of Kohei's mother for her son, for the weaknesses in the later parts of the film. But he gives his characters depth -- there is more sympathy for Iemon in the film than in more traditional versions of the story, which has been filmed many times.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Images of Ghosts Have Endured in Japan for Centuries

A New Exhibition at the National Museum of Asian Art displays Haunting, Colorful Woodblock Prints

— Roger Catlin | April 26, 2024

The Ghost of a Fisherman, Tsukioka Kogyo, woodblock print, 1899 National Museum of Asian Art

Oiwa’s husband wanted to remarry his rich neighbor, but his wife was still very much alive. He first tried poisoning Oiwa, but it disfigured her horribly rather than killing her. Then, he threw her into a river to drown, which was indeed successful. But later, when he returned to that river, Oiwa’s ghost rose from the water to haunt him no matter where he fled.

Foreboding depictions of this Japanese ghost story and others like it populate the “Staging the Supernatural: Ghosts and the Theater in Japanese Prints” exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art.

Going back centuries, ghost stories carry great resonance in Japan. The over 50 works on display, created from the 1700s to the 1900s by Japanese artists, show the lingering power of woodblock print art and the stories that the art represents, which continue to flourish in Japan today. Coming out of the theater traditions of kabuki and noh, the prints proved equally as popular as the performances.

The story of Oiwa, the faithful wife who returned as a ghost to haunt her murderous husband, was told in the 1825 kabuki theater production of Ghost Story of Yotsuya on the Tokaido by Tsuruya Nanboku IV. Though the supernatural had long been part of Japanese culture, the Edo period (1603-1868) and this specific production gave permanent prominence to the genre, says Kit Brooks, co-curator of the exhibition. The production toured more extensively than earlier variations and featured the potent special effects of flames and actors spurting blood and flying via wires.

Artists reproduced images from this ghost play and others of the era for clamoring patrons who wanted a souvenir of the production and its specific actors, often identified in the prints, and to recall the stories.

Left: Tsuchigumo, from Prints of One Hundred Noh Plays (Nogaku hyakuban), Tsukioka Kogyo, woodblock print, 1922-1925 National Museum of Asian Art Right: Oiwake: Oiwa and Takuetsu, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, woodblock print, 1852 Oiwake: Oiwa and Takuetsu, no. 21, from the series Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kisokaido Road, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, woodblock print, 1852 National Museum of Asian Art

Kabuki, which originated in the Edo period, was known for its stylized performances and intricate special effects that made it a popular entertainment for broad audiences.

“Whether it was tricks on the stage in terms of trap doors, lots of props, synthetic blood, contraptions that would have characters on wires, flying through the theater—these things were obviously conveying the presence of ghosts,” Brooks says.

Productions featured “spirit flames,” or fire that indicated the presence of ghosts. “Kabuki is very overtly entertaining in terms of bombast,” Brooks says.

Thousands of prints were created and made available at surprisingly populist prices. In the 1840s, Brooks notes, someone could buy a single-sheet multicolor woodblock print for the price of a noodle lunch.

Such colorful, vivid examples rarely survive after nearly two centuries, especially the prints that involved paper flaps that lift up, meant to reflect complicated stage effects.

One such elaborate woodblock print in the exhibition, made in 1861 by Utagawa Kunisada, shows the body of Oiwa pulled to the surface with a fishing hook and, by raising the flap, the body of a second corpse, a servant whose fingernails kept growing after his death.

This trick is even more effective onstage, since both corpses were portrayed by the same actor, doing a quick costume change.

By the 1860s, the stage trick had been used for nearly 40 years, and in that decade, real water tanks were used onstage. Brooks says prints were created to commemorate the trick. The prints are rare, especially those that survived fully intact.

Ghosts had also been prominent in noh theater going back centuries and aimed at a more elite, discerning audience.

Shakkyo, from the series One Hundred No Plays, Tsukioka Kogyo, woodblock print, 1922-1927 National Museum of Asian Art

Noh started in the 14th century “but dates back much earlier to harvest rituals and entertainments at shrines and temples,” says co-curator Frank Feltens. Those rituals involved dances, chants and characters using elaborate wooden masks. Donning a mask meant “you are basically assuming not just the essence of that role—you’re becoming it,” he says. “It’s a kind of spirit transmission that happens for them.”

Noh may have died out, Feltens says, had it not been revived as a cultural currency when Japan was reinventing itself in the mid-19th century as a more modern nation-state.

The 19th-century woodblock artist Tsukioka Kogyo tapped into the growing interest in noh by not only documenting its fearsome characters, but also clearly indicating the actors beneath the masks to the point of creating behind-the-scenes images of the theater for the first time.

“This peeking behind the scenes is almost sacrilegious in a way because it takes the mythology of noh away,” Feltens says.

Noh stories may not have been as bombastic in ghostly reproductions as kabuki, but the form was instead “capturing stories of the distant past, and those stories are often associated with specific sites, specific locales scattered throughout Japan,” he says.

Those stories are told through spirits associated with the sites, and the spirits are conduits for local memory, he adds.

So why have ghosts endured in Japanese cultural traditions, and why the big revival in the Edo period?

Collector Pearl Moskowitz, who, along with her husband Seymour Moskowitz, gifted hundreds of prints to the museum, posits in the exhibition catalog that it may have been a way to reflect society in a changing time. “My guess is these tales of ghostly hauntings acted as forms of justice in a feudal society in which the authority of the ruling class was absolute,” she writes in her essay.

In such an unjust class system, “it was kind of a catharsis in watching these kinds of plays where ghosts could take vengeance in ways they weren’t able to, and get justice achieved through these revenge plots in a way that might have been very satisfying,” Brooks says. “And samurai were often villains in these stories as well, so that lent some credence to that theory.”

It’s difficult to know how many prints were made at the time, Brooks says, adding that people still make them with traditional methods, and a practitioner could make 200 in a morning.

Viewers can likely connect these images of specters to modern Japanese horror in films like 1998’s Ringu, and its English-language remake, 2002’s The Ring.

“Japanese ghosts are things that people know from Japanese horror films,” Brooks says. “So even if they’re not specialists in the subject, you can still see things that you’d recognize and be interested in.”

Originally set to open around Halloween in October 2023, the exhibition was postponed for almost six months following the discovery of a leak in a nearby stairwell.

“Even though nothing was in danger, you obviously have to have an overabundance of caution, so we took everything out,” says Brooks. “It meant the second installation went very, very fast.”

“Staging the Supernatural” will run until early October at the National Museum of Asian Art—closer to the Halloween connection it was denied last fall.

But people are encouraged to also contemplate the supernatural in the summer. “In Japan, summer is the ghost time period,” Brooks says. “People tell ghost stories in the summer because it’s hot and sweaty and humid, and they make you shiver, which makes you cold.”

— Roger Catlin | Washington, D.C. freelancer Roger Catlin has written about the arts for AARP The Magazine, The Washington Post and other outlets. He writes mostly about TV on his blog rogercatlin.com.

#Japan 🇯🇵#Images of Ghosts#Endured#Exhibition | National Museum of Asian Art#Haunting | Colorful Woodblock | Prints#Smithsonian | Magazine

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Ghost of Yotsuya

1959 film

Director: Nobuo Nakagawa

November 6, 2021

I watched an old horror movie which is one of the adaptations of the timeless Japanese ghost story, “Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan", written in 1825. It is about this lowly samurai who kills his wife Oiwa because he wants to get married with another woman from a rich family. However, Oiwa haunts her husband after she dies, which ultimately wrecks his life. I wonder why this story has entertained many people for nearly two hundred years. A man cheats on his wife and she tries to get back at him. Of course, she is the ghost. That may be unique, but other than that, the story seems like a typical motif to me.

However, it has got me curious since I learned from the Internet that it was based on what actually happened during the author's time. According to an article, that couple existed back then. Oiwa ghosted her husband after he cheated on her. And after a while, there were a series of mysterious deaths around him. I imagine how people at that time reacted to that affair. They may have enjoyed gossiping with their friends about it. Or it was something like fake news, so they may have felt uneasy about it. I think through this story we can hear the voice of the past, which isn't really any different from what we hear in the present.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ghost of Oiwa, Katsushika Hokusai, c. 1831-1832, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Japanese and Korean Art

Ghost tale of Iwa is a famous story based on the real event, known as "Yotsuya Kaidan (Ghost Tale in Yotsuya)", later had been made a Kabuki play by Tsuruya Nanboku. An unemployed samurai, Iemon married Iwa, a daughter of a warrior family looking for a man who can succeed their family name. After the marriage, he poisoned and killed his wife, and was haunted by the ghost of his wife.

Size: 10 3/8 × 7 7/16 in. (26.3 × 18.9 cm) (image, sheet, vertical chūban)

Medium: Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/65717/

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ignore the redness as it’s fresh, but I got my graduation present the other day! Thank you so much to the amazing @nipinet at @giige.co on Instagram for the fantastic work!!! I wanted to get my favorite ghost, Oiwa - she has inspired me for years, and I wouldn’t be where I am without her influence. Oiwa is from the Kabuki play “Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan,” by Tsuruya Nanboku IV. This particular version of Oiwa is inspired by a print done by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, which I was lucky enough to see in person years ago. Fun fact, the visual effects highlight of the play was a part where the actor playing Oiwa would emerge from a lantern, with the robe actually on fire. Artists looking to show this scene sometimes combined the imagery of the actor emerging from the lantern into a personified lantern, which is what I have here!

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Freedom of Expression Ep 45 - Walking from Kishibojin, Haunted staircase.

00:00 J: Ah, this, this! Akamaru Bakery.

00:20 K: So, as to why we are here..it will be a mystery to everyone I think.

J: Haha

K: Joe just really wanted to eat this bread.

J: Thats right.

K: So, we came here.

J: Yes.

K: Akamaru Bakery.

J: Yep, Akamaru Bakery.

K: Where is this?

J: Its Zōshigaya. Well, Zōshigaya is just up there, but this place probably only locals know about. Its on Tsurumaki Street. This is a very small shopping street, but Akamaru Bakery is here. I found this place by chance before, and it was really good.

T: What did you get?

J: Kaoru?

K: Chicken Nanban

T: I got a hot dog.

J: I got this tuna and egg mix.

K: I wanted to get that, but I thought I shouldn't if you are getting it.

J: Haha, no, no, no, that makes me look bad.

K: Hahah.

J: This is ¥190, right?

T: Its cheap, isn't it?

J: It is cheap! Ok, lets stand and eat.

T: Yep.

J: Ok, lets go for it. Apologies to the locals, we are not trying to be rude. Its a food report. This kind of bakery is quite rare these days, isn't it? They're all like new, stylish ones now.

K: *eats* Mm.

J: *eats* Mm, tastes good.

K: Yeah, its good.

J: The bread is really soft too.

T: Yeah.

J: I didn't eat before this.

K: If this was in my neighborhood, I would come every day.

J: Absolutely. Ah, delicious. So, this is like an 8 min walk from Zōshigaya station, right? Its a bit of a walk, but you'll be able to find it online if you search for it.

T: Ths is good. Its delicious.

2:25 J: (*At station*) Well now..

K: Where is this?

J: So this is the tram on the Toden-Arakawa line.

T: Its Kishibojinmae station.

K: Ahh, so ??? (*Facing away from camera with mask on...couldn't clearly make out what he said*)

J: Thats it. So, we are gonna move to a different spot from here.

T: Yep, its been all funfunfun before now, but this time we are gonna go looking for some Tokyo mysteries. So, we'll get on this train and go to a certain place.

J: Tokyo Sports is all about mysteries, monsters, and UFOs, right? (*Couldn't really follow the rest of this exchange*)

*They get on, then off the train at the next spot*

3:29 T: The mystery spot that I am gonna introduce is this bridge. Omokage bridge (Omokage=face/visage).

J: It just looks like a regular bridge.

T: Its a really short bridge. Its almost not a bridge. This explains the name (*points to info board*). So, actually, on the otherside of the bridge there used to be the criminal execution center for Zōshigaya.

J: Ahh, so this is not exactly the river Styx, but..

T: Yeh, and they would part from thier family on this side of the bridge, and be taken over to the other side.

J: I see.

T: Its just a theory, but its thought that its called 'Omokage/visage brige', because they left the memory thier faces here. But there is also a history to this brigde. You know the story of 'Yotsuya Kaidan'/The Ghost of Yotsuya?

J: Yep, yep.

T: With Oiwa san..

J: Like 'I curse youuuu'

T: Yeh, yeh, yeh. Do you know the story of Oiwa san?

J: Yeh, I do. Like 'One plate, two plates..'

T: No, thats Sarayashiki, thats a different one. So, what happened was, there was a man, and his wife called Oiwa. The man became annoyed with her, and she was made to drink a poison which scarred her face. Then he forced her to seperate from him. The woman cursed him, saying she would come back as a ghost. This woman Oiwa was nailed to a door post, and thrown in the river to be washed away, there's a scene like that, right? Its thought that this is the spot she was thrown in the river. So, this story, Yotsuya Kaidan, came about as a Kabuki play after its writer, Tsuruya Nanboku had gathered up a lot of these kind of local rumors during the Edo era. We don't know if Oiwa san really was washed away here, but we know this kind of thing did happen. Its only a short bridge, but its got this kind of history going back to the Edo era.

J: ???*1

T: Actually, I used to live around here.

J: Ehh? Why in such a frightful place?

T: It was cheap.

J: Is this in Shinjuku ward?

T: No, its in Toshima ward.

J: Oh, Toshima?

T: Just on the verge of Shinjuku.

K: It says Shinjuku here.

T: Yes, but..Oh, the other side is Toshima.

J: Where we are stood now is Shinjuku. Its next to Waseda, right?

T: Should we cross the bridge?

K: Yeah, lets cross it.

6:50 J: The river is pretty, isn't it?

(*Next is short exchange about the sakura leaning into the river, and execution spot over on the other side, which I can't make out clealy due to them all facing away from the mic, and very loud traffic passing simultaneously*)

T: So you see, this place is very historic.

J: It makes a shiver run down your spine when you think of it.....*shudders*. Sorry, its just being in this place.

K: Ok, should we head to the next spot?

J: Yeh, should we go?

K: Its a different place next.

*In the suburbs*

7:46 K: Where is this?

J: Here in Bunkyō Ward, they call this place Nezucchi (*The name of a comedian who is good at tellIng riddles*)

T: Nezucchi?

J: Haha

K: He lost it. haha

J: Sorry, Im embarrassed now, haha. Well, actually, they call this area Yanasen/谷根千, which is the neighborhoods of Yanaka, Nezu, and Sendagi together, and we are in Nezu today. Its a very quiet surburban area, but this place was voted for by a listener, or rather a user, as a good mystery spot. We recieved this email, so Kaoru could you read it out?

K: (*reading*) Its from 'Yasubeniisann'. It says, 'This is quite famous, but in Nezu there is a haunted staircase. When you go up the stairs there are 40 steps, but going down, there are only 39'....Um..did..

J: We already spilled the mystery.

T: Yeah.

J: Well, we already spilled the mystery , but yes, this is what we are going to see. A mysterious set of stairs. Lets go.

8:49 K: (*approaching the stairs*) Right up to the top, yeah? Not half way?

J: Yeah, I think right up to the top.

K: Both sides are the same, right?

J: Seems like it. Which side is the way up?

K: Eh? You could go up either side, right?

T: You mean like on an escalator where one side is up and one side is down.

J: Should we try counting the steps?

K: You're too eager, haha.

T: Which side should we do, the right side?

J: No, lets go with the left side.

T: Like in Kantō.

J: Yep, Kantō style.

K: Ok, Im gonna start.

J: Ok...1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7....

9:57 K: (*reaching the top of the staircase*) 39 steps.

J: 39? Yep I got 39 too. And next, if we go down..

T: On that side?

K: Will it be 39?

(*They walk downstairs *)

K: (*Reaching the bottom*) Eh?

T: Wasn't that 40?

K: I got 39.

T: Huh?

J: Huh?! I got 39. You got 40?

T: Yeah, I got 40.

J: Eh?! Hang on, whats going on?

10:55 K: (*Re-reading the email*) It says there are 40 steps going up.

J: 40 going up?

K: Are they including this? (*points to first concrete step on level with the ground*)

J: Oh, is that it?

K: If they are including this..

J: Yeah, if thats included, then..

T: I see.

K: I'll try starting from this. (*starts going up*)

J: Maybe you're supposed to go up the other side.. I can hear you.

T: Im out of breath..

J: Oh, you're carrying the bag..

T: Its embarrassing, im out of breath.

J: Its this step, this one.

11:36 K: (*Gets to top of stairs*) Ah, I see.

J: (*Getting to top*) 40!

T: (*Starting from the bottom*) This is the first step, yeh? 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9....

J: Haha

T: Then across?

J: No, no, diagonally.

T:...38, 39, 40.

K: You included the very first step at the bottom, right?

T: Yes...huh?

K: Huh? Really? How come only I'm different?

12:30 T: (*Going down*) This is the first one. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6....... ....... 37, 38, 39, and this is 40.

K: You're not counting this one, are you? (*To J*) This one is ???*2

J: Ahh, thats the difference.

13:08 J: Do we count this one? Thats the problem. According to the email, there are 40 steps going up, and 39 going down.

K: Its like can you count this as 1..?

J: Yeah, thats it.

K: Im not sure.

T: Its raised by about 5cm.

K: Well, I mean...we'll digest that bread easily.

J: Haha, yeah, we can definitely say we exercised today.

T: Its been quite tough for the staff doing the filming.

J: Yeah, haha. While we were going up one by one, they were going up and down each time. But what is our verdict about this?

K: Was is right? If this is the first step?

J: Im pretty intrigued about this.

T: Well, let's give our answer here. To conclude.

J: As a last word?

T: Yeah.

J: Well, it depends on whether or not you count this as the first step. If you do count it, then there is 40 steps going up. But if you look over here, this side is barely elevated from the ground at all. So you end up taking the second level as the first step.

K: Yeah.

J: Thats it right? And back over here, the first step is more elevated, so you would make that number 1.(*Starts climbing*).1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6...

K: (*To T*) Ok, shall we go?

T: Yep, lets go. Bye Joe.... ... ... That was fun.

K: Yeh, it was. (*Too windy to make out what they are saying*)

T: I wonder if Joe is still doing it.

15:00 J: (*Coming downstairs*) They're not here? They left me. Hello? You two? What? There's no one here.

Takabayashi: That was 39.

J: Was it 39? So, yes, that means going up is 40 steps, and coming down is 39 steps. The others have already left, so if you'd like to try this, its in Nezu...the haunted staircase. Please come and have a go, get some exercise.

15:31 T: He didn't call out for us to wait, right? haha....... ... ... Haha, here he is.

J: ??? (*No idea what he means here*)

T: You didn't realise we'd gone?

J: No, I didn't. When I came down there was no-one there, so it was a bit lonely. I closed the segment by myself.

T, K: Hahaha

T: How about this haunted staircase?

J: What do you think, Kaoru?

K: There was no ghost.

J: There wasn't, was there.

K: Its more like a mistaken staircase.

J: Yeah.

T: Ah, I see. Haha. To be accurate, the mistaken first step.

J: Yeah. When you go up, the fist step on one side looks as if its slightly elevated, so..

T: Yeah. We could go looking for other mysteries like this.

J: Yeah, lets solve them all!

K: So it seems as if we can use this one then.

J: Ah, thats good! We didnt waste our effort. So, if anyone knows any other mysteries that we could solve..?

K: Yeh, anything is ok, just let us know.

J: We'll solve them.

K: Ok, well, we can finish here. Please subscribe. Thank you very much.

*1,2 Couldn't catch.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Actors Nakamura Takesaburo as Shikishi Naishinno and Tsuruya Nanboku as Gengoro in the play "Tategami Teika Kazura," performed at the Ichimura Theater in the eleventh month, 1719, Okumura Toshinobu, 1719, Art Institute of Chicago: Asian Art

Clarence Buckingham Collection

Size: 11 1/2 x 5 1/2 in.

Medium: Hand-colored woodblock print; hosoban, urushi-e

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/8216/

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales

Genre: Horror, action, romance, tradition

Anime television series

Episodes: 11

Year: 2006

Studio: Toei Animation

Score: (8/10)

Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales is a Japanese animated horror anthology television series produced by Toei Animation. This is made up of three stories: “Yotsuya Ghost Story”, an adaptation of the classic Japanese ghost story written by the 18th century kabuki playwright Nanboku Tsuruya IV.; “Goddess of the Dark Tower”, based on the play by Kyōka Izumi; and Goblin Cat, an original story by Kenji Nakamura and Michiko Yokote.

“Yotsuya Ghost Story” – Nanboku is the narrator. Iemon Tamiya is a ronin samurai who marries a beautiful woman named Oiwa and he made many sins to reach his goal. Oiwa is happy with her married life and the birth of their child with him but later he changend his feelings for her and new woman appears. Iemon Tamiya give up to his desire and it will bring punish to him and people who made death Oiwa by herself as ghost who want revange. Episodes: 1-4.

Tenshu Monogatari story is in medieval Japan. It is story of a forbidden love between a god and a human. In beginning story gang is in castle but later they were eated by forbidden gods and nobody survive. Later Zushonosuke Himekawa lost his falcon named Kojiro. His master Lord Harima send him to find him. Zushonosuke’s search him, though it leads him to a chance encounter with a beautiful woman bathing in a lake. Zushonosuke falls in love with her at first sight. Falcon has fled to the castle keep of Shirasagi-jo, Zushonosuke is ordered to go there to bring the falcon back. At the castle, Zushonosuke is surprised to find the woman he encountered before, who introduces herself as Tomihime (Princess Tomi), beginning their forbidden romance. They met each other for short time to come back they before life but later they met again to be with each other again. They sacrifice somthing to be each other. They punish evil invaders. Episodes: 5-8.

Bake Neko is presented like a play, with sliding screens taking the place of curtains. The story takes place in the Edo period, with Ukiyo-e style artwork. A wandering medicine peddler arrives at the house of the Sakai Clan on a wedding day, however as he crosses the threshold to the clan household he senses something is not right and he has got good feeling about it. The family sold their only daughter’s marriage to the Shiono Clan to clear their debts. As the bride crosses the threshold to meet her wedding escort, she dies mysteriously and medicine peddler was accused for this murder but he was innocent. Appears deamon who want revange. To save their lives, the peddler must know the truth and reasoning behind the demonic attacks to use his special weapon. The medicine peddler discovers the dark secrets of this family. Kayo decided that she can no longer serve the household and will return to her parents’ home. Kayo and Odajima bury the cat next to the old well, which is Tamaki’s grave. the spirits of Tamaki and the cat cross the threshold and leave the house of their torment and deaths. The medicine peddler leave this place and he went to other direction. Episode 9-11.

This anime has got dark side but story tell that humans are more evil and brutal with they lust than demons. In this anime appears three animals: rat, falcon and cat. They have special meaning in this title they are somthing like symbol.

This anime is more for adults because it contains brutal scenes.

—Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales— Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales Genre: Horror, action, romance, tradition Anime television series Episodes: 11 Year: 2006…

0 notes

Text

Katsuko Wakasugi in Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan (Nobuo Nakagawa, 1959)

Cast: Shigeru Amachi, Katsuko Wakasugi, Shuntaro Emi, Ryuzaburo Nakamura, Noriko Kitazawa, Junko Ikeuchi, Kikuko Hanaoka, Hiroshi Hayashi, Jun Otomo, Shinjuro Asano. Screenplay: Masayoshi Onuki, Yoshihiro Ishikawa, based on a play by Nanboku Tsuruya. Cinematography: Tadashi Nishimoto. Production design: Harayasu Kurosawa. Film editing: Shin Nagata. Music: Michiaki Watanabe.

Keisuke Kinoshita's 1949 version of the much-adapted ghost story, Yotsuya Kaidan, jettisoned the supernatural in favor of the psychological, turning the protagonist, Iemon, into a somewhat more sympathetic, even tragic figure. But ten years later, Nobuo Nakagawa went straight for the horror: a bloodthirsty, ambitious Iemon (Shigeru Amachi), who doesn't even need Naosuke's (Shuntaro Emi) Iago-like promptings to descend straight into murder. In fact, if you try to apply psychology to Nakagawa's Iemon, you'll run up against some blank walls: It's hard to understand why Iemon in this version even bothers to settle down to a life of umbrella-making after his slaughter of Oiwa's father and his complicity in Naosuke's dispatch of Yomoshichi (Ryuzaburo Nakamura), his rival for Osode's (Noriko Kitazawa) hand. By this time, Iemon is steeped in blood so far that "returning were as tedious as go o'er," to put it in Macbeth's terms. In this version, the ghosts of Oiwa (Katsuko Wakasugi) and Takuetsu (Jun Otomo) are particularly real and vengeful, not just phantoms of Iemon's imagination, as in Kinoshita's version. They lead Iemon into slaughtering Ume (Junko Ikeuchi) and her father and finally to his own doom. Nakagawa's film lacks the subtlety of Kinoshita's, but in the end I think that's for the good: What you want from a ghost story is catharsis, not irony.

0 notes

Text

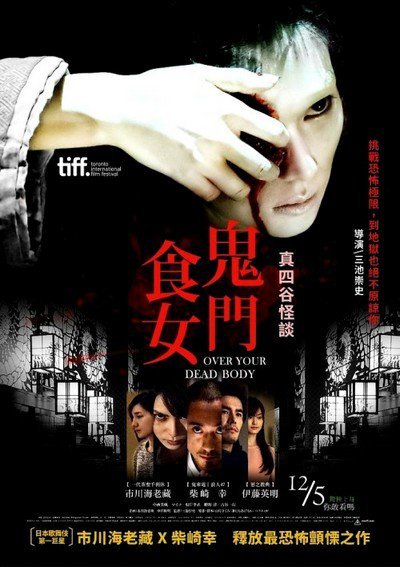

Over Your Dead Body 喰女 クイメ

2014 - dir. Takashi Miike

Based on the 1825 kabuki play "Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan" (東海道四谷怪談) by Tsuruya Nanboku.

#kabuki#film#takashi miike#over your dead body#ebizo ichikawa#kou shibasaki#hideaki ito#yotsuya kaidan

4 notes

·

View notes